Born: Otilija Ester Berger, October 4, 1898, Zmajevac, Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Croatia)

Died: April 27, 1944, Auschwitz, Poland

Matriculated: 1927

Locations: Austro-Hungarian Empire, Yugoslavia, Croatia, Germany, Sweden, UK

“Art in the traditional sense and design in the new sense, that’s impossible. For the ‘traditional’ is never art,” stated the weaver and textile designer Otti Berger, in a 1928 interview. With her own unique combination of the keenest sentience, technical expertise, and an incredibly rich, innovative, and creative imagination, along with her talent for teaching, she was at the forefront of the Bauhaus avant-garde. However, as a Jewish woman her artistic potential would be cut tragically short. While living in exile in Britain after the 1933 Nazi takeover in Germany, she was offered a professorship in the United States of America. But first she decided to visit her seriously ill mother in her Croatian hometown one last time. With the outbreak of war in 1939, she was no longer able to obtain a visa and was deported with her family to Auschwitz; facts that lay bare the barbaric arbitrariness of Nazi policies and their tragic consequences.

When Otti—Otilija Ester Berger—was born in 1898, her small hometown of Zmajevac in the Baranya region of present-day Croatia still belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire; beginning in 1918 it was part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Even today, Zmajevac is also known by its Hungarian name, Vörösmart, which is why Berger is sometimes considered a Hungarian artist. Under Emperor Franz Joseph I’s reign, the Jewish population (of nearly five percent) was granted unrestricted residence and religious freedom for the first time. It was, however, by no means certain that Berger would attend a girls’ secondary school in Vienna and, from 1922 to 1926, she studied at the Royal Academy for Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, Croatia’s capital. She later criticized the academy as an “insipid site of transmission.”

In January 1927, she enrolled in the Dessau Bauhaus, where three teachers particularly supported her: Paul Klee, who, next to Kandinsky, was the most important instructor of form and color theory; her friend, Gunta Stölzl, textile designer and since 1927, head of the weaving workshop; and László Moholy-Nagy, director of the preliminary course (Vorkurs) and the metal workshop until 1928.

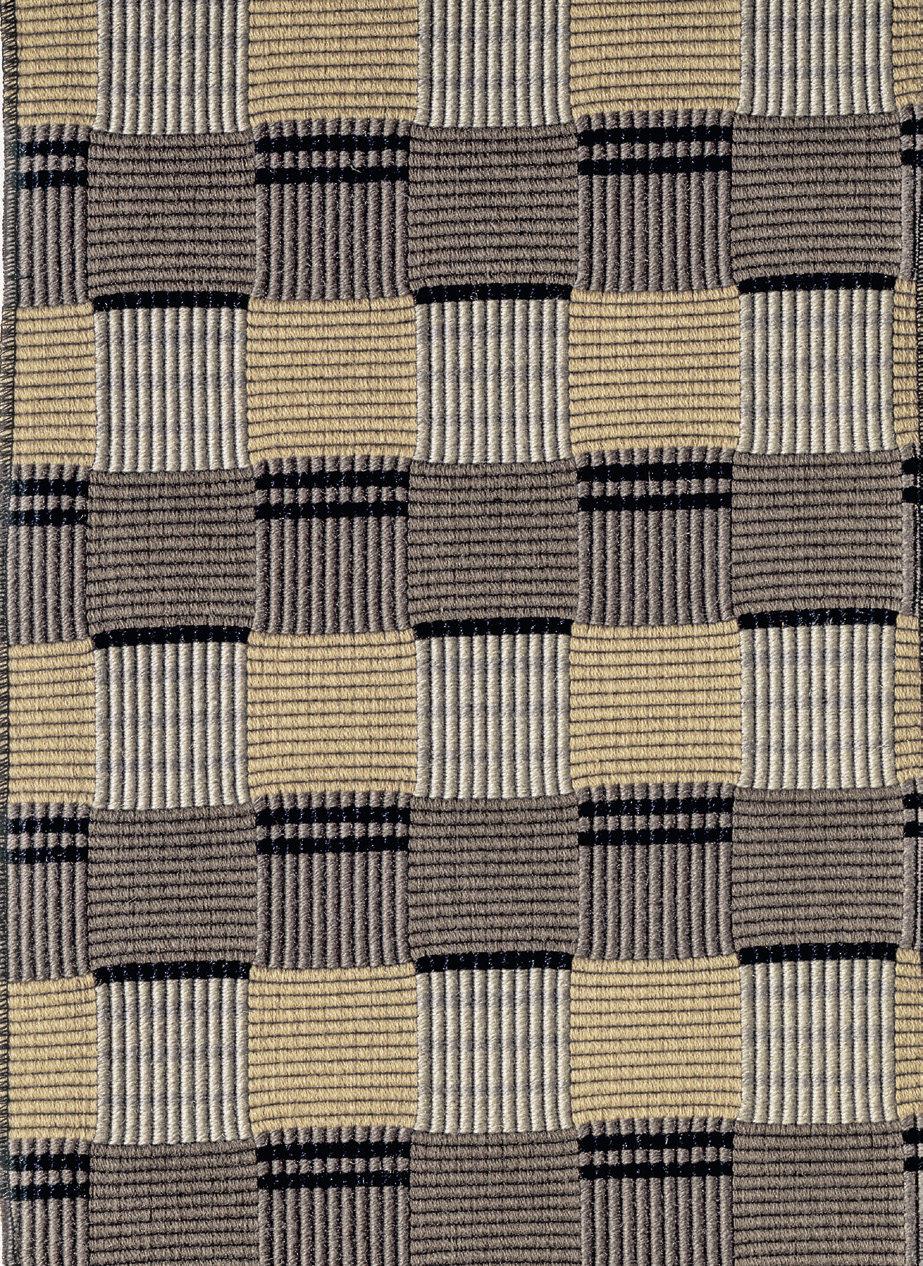

Otti Berger, sample of a chequered upholstery fabric (Cassina/Storck fabrics)

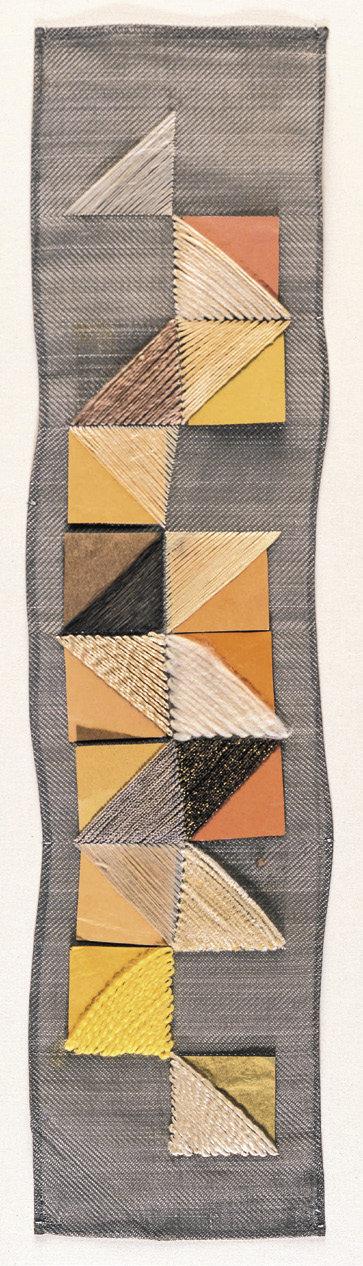

In his classes, Moholy-Nagy valued not only technical, experimental work but particularly sought to train students’ sense of touch. He had students make so-called Tasttafeln (“tactile boards”); Berger’s work evidently impressed him, since he published it in his theoretical text Von Material zu Architektur (From Material to Architecture). Her board, composed of a horizontal strip of metal fabric embroidered with triangles of various colored threads, into which colored paper squares can be inserted, can be “read” almost like braille with one’s fingers and decoded like a kind of “material alphabet.” This work exhibits Berger’s very particular sensibility for fabrics.

Otti Berger, “Tasttafeln” (“tactile board”) from László Moholy-Nagy’s preliminary course, 1928, threads on wire mesh, applied paper cards in different colors

Otti Berger at the high-warp loom, 1932

Her artistic talent is also evident in her many studies from Klee’s classes beginning in the fall of 1927. Her watercolor color-mixing and gradient studies appear both effortless and yet precise. Translating Kleeian laws of form and color directly into textiles while achieving maximum technical precision and functionality evidently came to her just as easily. Klee’s use of the musical term “polyphony” to refer to the effect of these methods in their systematic entirety—because of their ability to open the senses and mind, to heightened trans-sensory synesthetic and imaginative perception—corresponded fully to Otti Berger’s own cognitive-sensory abilities. “A piano cover [Flügeldecke], for example, can in itself be music, flowing, harmonious, full of melodies and vibrations,” she wrote in her essay “Stoffe im Raum” (“Fabrics in Interiors”) in 1930. The essay reads like a manifesto for the new direction of the Bauhaus weaving workshop and, at the same time, introduces other ideas. Berger mentions Pythagoras’s philosophical system of cosmic harmonics from approximately 600 BCE, for example, as well as artistic concepts of time such as the theory of harmonization (Harmonisierungslehre); taught by the music educator Gertrud Grunow at the Bauhaus Weimar until 1923, this theory primarily addressed the internal and external balance of sound, color, and movement. For Berger, transcending traditional forms of perception and expression in her Bauhaus studies was essential because a previous illness had left her almost deaf but with a heightened sense of touch, and this allowed her to “grasp” the nature of fabrics: “touching a fabric with your hands can be as pleasurable as a color to your eye or a sound to your ear.”

When Berger began studying under Stölzl in the Dessau weaving workshop, the primary goal was no longer to produce artistic, one-of-a-kind pieces, but to develop reproducible fabrics and patterns for mass production. It was here in the classroom that the transformation from hand-weaving to textile design took place, and students in the weaving workshop including Berger and Anni Albers—who both pursued this path enthusiastically—became successful industrial designers. In November 1929, after having spent a semester abroad at Johanna Brunsson’s weaving school in Stockholm, Berger and Albers temporarily replaced Stölzl, who had just given birth to her first daughter.

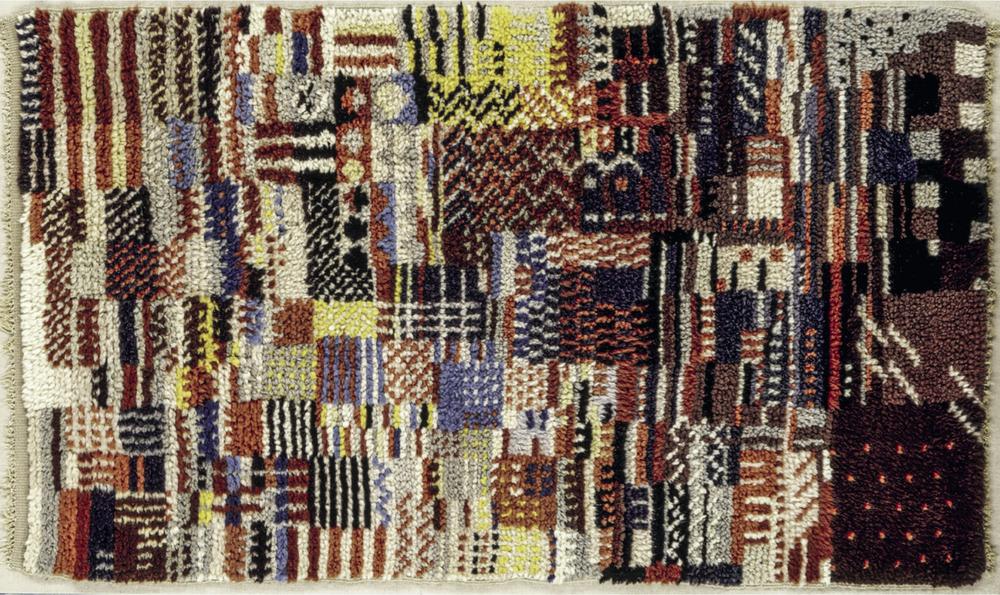

Otti Berger, knotted carpet, c. 1929, smyrna knot, wool on linen warp

“Touching a fabric with your hands can be as pleasurable as a color to your eye or a sound to your ear.”

Otti Berger

Berger’s responsibilities included producing fabrics for the National Trade Union School in Bernau, designed by Bauhaus director Hannes Meyer with the assistance of others including Lotte Stam-Beese. Based on her concept of “Fabrics in Interiors,” she analyzed and designed the textiles with regard to Moholy-Nagy’s principles of structure, texture, facture, and color in close relation to the new architecture. She agreed with Meyer that, in home decor, there is no room for superfluities and that practicality and functionality must be as prevalent as they are in architecture: “Why do we still need … flowers, vines, ornaments? The fabric itself is alive.” Yet she was annoyed with his inflationary use of terms such as “structure” and “function oriented weaving” (gebrauchsorientierteres Weben), as the weaving workshop had long-since formulated and implemented these principles before Meyer “reinvented” them and began repeating them like a mantra.

In a letter of recommendation from September 9, 1930, Stölzl expresses how impressed she was with the work of her student, one year her junior—“[Berger’s pieces] are among the best to be created in the department.” When, under increasing pressure from Bauhaus intrigues, including an anti-Semitic smear campaign, Stölzl resigned from the Bauhaus on September 31, 1931, she fully supported the decision to entrust the artistic and technical direction of the weaving workshop to Berger.

“[Berger’s pieces] are among the best to be created in the department.”

Gunta Stölzl

A year earlier, on October 5, 1930, Berger had taken her journeyman’s exam (Gesellenprüfung) in Glauchau, Saxony, and, on November 22 that same year, was awarded her Bauhaus Diploma. Now she was taking orders from large eastern German textile companies on her own initiative. Moreover, she became a member of the Bauhaus jury, which selected fabric for industrial manufacture. Her days as a workshop director came to an end when, in 1932, Mies van der Rohe became the new Bauhaus director and transferred the workshop’s management to his partner in life and work, Lilly Reich. Berger was offered a half-time contract, despite the fact that Reich initially relied heavily on her help; though she had made a name for herself as a designer, Reich did not know how to weave, which led to conflicts in the workshop. The Bauhaus swatch books from that time show elegant, high-quality fabrics that reflect the style and standards of both women but do not mention them by name. After her departure, Berger remained embroiled in a dispute over patent rights and remuneration for prototypes she had created, which lasted until the closing of the Bauhaus; ultimately, the school cheated her out of 800 Reichsmarks (approximately US$3,500 today).

After the Dessau Bauhaus was forcibly closed in the fall of 1932, Berger bought some of the school’s looms and workshop materials and opened her own studio in Berlin-Charlottenburg. For her, this was not only a workshop and business but also a research laboratory, in which she used experimental material combinations to develop new fabrics and concepts for customers, some of which she patented. In 1933, with Gropius’s support, she received several larger commissions from companies such as De Ploeg in the Netherlands and Wohnbedarf AG in Zurich, which soon confidently marketed her textiles under the label Otti-Berger-Stoffe (Otti Berger Fabrics). That same year, she undertook the interior design of the Schminke House, built by the architect Hans Scharoun in Löbau near Görlitz.

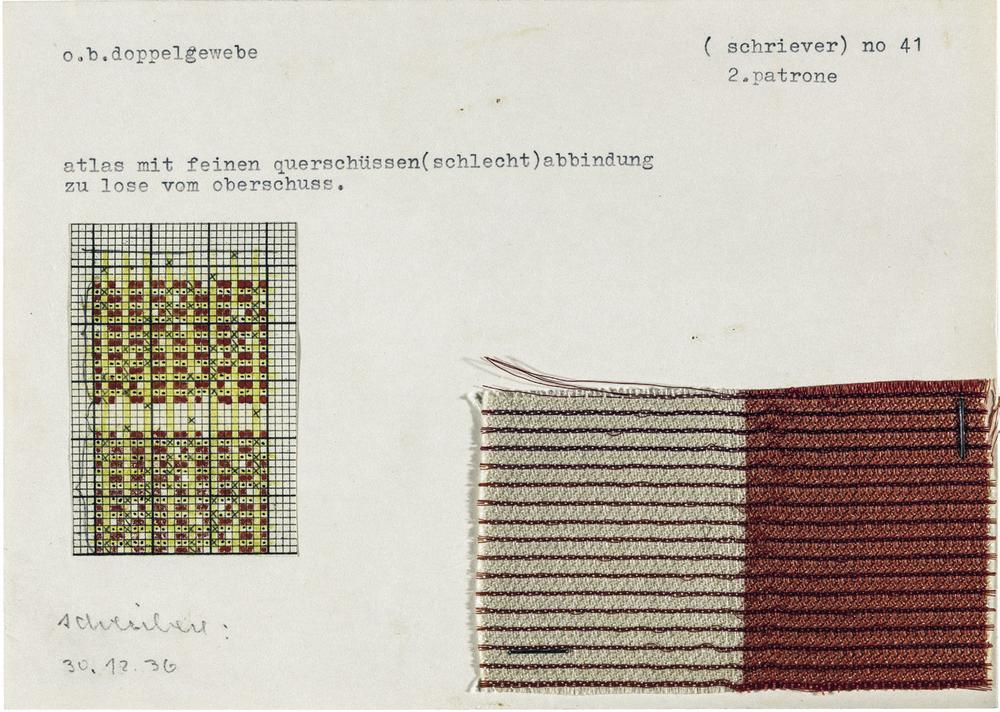

Everything changed in 1933, and Berger’s career quickly came to an end. Nevertheless, her work still remained publicly visible as a result of her persistence in registering patents and enforcing her trademark. In 1934, she obtained a Reich patent for Möbelstoff-Doppelgewebe (“double-weave furniture fabric”) and was accepted into the Association of German Craftsmen. In 1936, however, her membership application for the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, submitted a year earlier, was rejected; this in effect amounted to a professional ban (Berufsverbot). However, in order to keep her German residence permit as a “non-Aryan foreigner,” she would have had to provide proof of a steady income.

Under these circumstances, in early 1937, she made contact with an English textile company and, in September, immigrated to the United Kingdom, where she was initially taken in by Lucia Moholy in London. She later moved to the textile city of Manchester, where she found work that was almost exclusively unpaid; the sole exception was the Helios company, where she had a paid temporary position for five weeks. In December 1937, however, she succeeded in having one of her fabrics patented in London. Her partner, the architect Ludwig Hilberseimer, with whom she was planning a life together in the USA, wrote her letters of comfort, but, because of her hearing impairment and poor English, she felt increasingly isolated: “I sit, day after day, night after night, alone and sad and dejected,” she wrote in 1938. But then she found renewed hope: Moholy-Nagy invited her to the USA to head up the weaving workshop at the New Bauhaus in Chicago. But her start date was delayed, whereas Hilberseimer, who had also been invited, left for Chicago in August 1938. Before leaving, he visited Berger in London. It was against Hilberseimer’s advice that Berger made that last trip to see her mother in Croatia and lost her chance to ever leave again.

Otti Berger, design for double weave fabric, 1936

Although her mother’s condition improved, Berger was no longer able to get a visa for the USA. Berger likely never knew that Marie Helene Heimann (or Marli Ehrman), also a talented Bauhaus weaver of Jewish origin, still managed to emigrate in 1938, after Moholy-Nagy chose her over Berger to oversee the weaving workshop in Chicago. In a last surviving letter from Berger from 1941 she complains about the cramped quarters at home and, still hoping to emigrate, discusses work on a rug. After that, contact with her was lost.

In 1941, after the collapse of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Croatia essentially became a vassal state of Hitler and Mussolini under the fascist Ustashe regime, that also wanted to free their country of “anti-national elements” and, to this end, erected a total of twenty-four camps. That her family was deported directly to Auschwitz, without first being detained in one of these camps was evident from the Russian records published in Yad Vashem in 2005. In addition to giving the exact location and date of her death for the first time—“Auschwitz Camp, April 27, 1944”—Berger’s last place of residence during the war is provided; her hometown of Zmajevac.