Born: June 5, 1908, Göppingen, Germany

Died: April 29, 1952, Göppingen, Germany

Matriculated: 1927

Locations: Germany, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), Italy

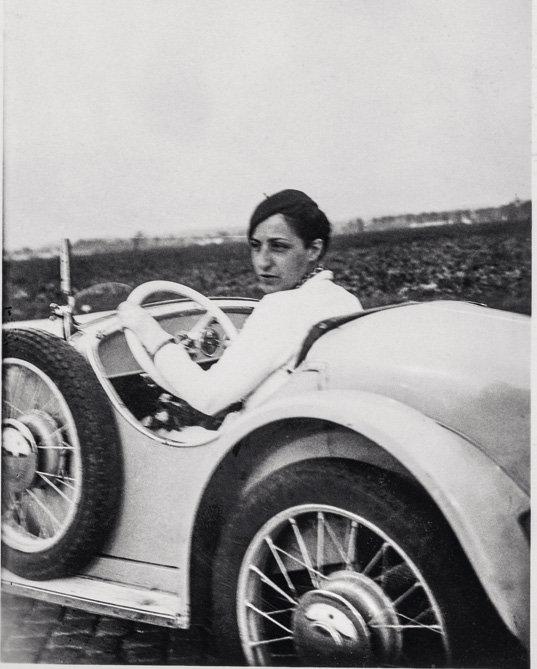

Behind the wheel of her car, Margarete Dambeck caused a stir wherever she went. This always elegant woman was, after all, a highly trained textile designer and prototype of the confident and independent “New Woman” of the Weimar Republic. When she died of a stroke at only forty-three years old, she left behind not only a young son but also her own textile workshop and the unfulfilled ambition of passing on the Bauhaus’s teachings to future generations.

The fourth and youngest daughter of a master craftsman of brushes and Liberal-Democrat town councilor in Göppingen, Germany, Dambeck grew up in the Swabian countryside. After graduating from the girls’ high school (Höhere Mädchenschule), she attended the local women’s vocational school (Frauenarbeitsschule) and focused on fashion and drawing. On a visit home, her childhood friend Georg Hartmann, son of Göppingen’s mayor and a student at the Bauhaus, convinced her to follow him to Dessau. Shortly before her father passed away in 1927, he gave permission to his then nineteen-year-old daughter to leave the provinces for the most progressive reform school of its time. She was accepted to the school, admitted to Josef Albers’s preliminary course (Vorkurs), and trained in the weaving workshop under Gunta Stölzl. She developed a special relationship with Oskar Schlemmer, who had spent part of his childhood in Göppingen, and became friends with his wife, Tut. In 1930, she received Bauhaus Diploma number twenty-eight. She left Dessau but kept in touch with her best friend Otti Berger as well as Hannes Meyer, in exile in Mexico, and Gunta Stölzl and Max Bill in Switzerland.

Her first job took her to Prague, where, with the help of former Bauhaus friends, she found a position in the upscale fashion house Haute Couture Rosenbaum in 1931 and quickly rose to become one of the company’s heads. She began a relationship with her former Bauhaus friend Werner David Feist and occasionally travelled with him to Italy. For day-to-day travel, Dambeck bought herself her first car—a BMW Dixi. In 1933, to be closer to the Schlemmer family in Breslau, she applied and was hired as a pattern designer at Cohn & Sons in Reichenbach (Upper Silesia), a textile company specializing in artistic fabrics. The Jewish family who owned the business, the Kantorowiczes—with whom she and her little dog, Wassily, even lived temporarily—had been impressed by her designs, which recalled the Italian fashion lines that were all the rage. As she herself wrote, she spent every spare minute with the Schlemmers in Breslau, buying herself a DKW Reichsklasse cabriolet for these trips.

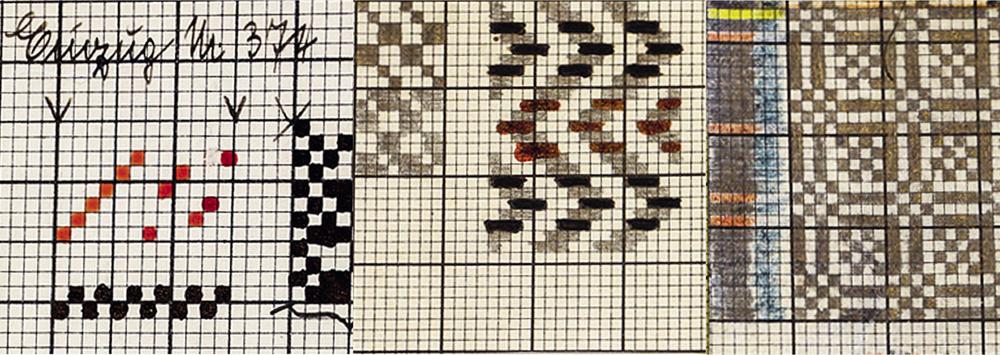

Margarete Dambeck designs from the workshop for artistic weaving patterns, late 1940s

According to family lore, Dambeck fought to get the Kantorowiczes an exit visa to save them from Nazi detention; to achieve a more Aryan appearance during her negotiations with authorities she even underwent plastic surgery on her prominent nose. Dambeck managed to persuade the Gauleiter (Nazi district official) to allow the wealthy Kantorowiczes to immigrate to England; she even arranged shipping of their valuable art collection by falsely claiming that it was to be part of a Bauhaus exhibition in London. In 1942, through a marriage advertisement, she met the stylish Walter Keller of Offenbach, and married him in July of that year at age thirty-four; because of this, she turned down an appointment as head of the School of Art and Fashion’s textile department in Mulhouse (Alsace). She moved with her husband to his family home and, in early 1943, became pregnant. However, that same year, she would suffer two cruel twists of fate: soon after their first wedding anniversary, her husband died of a congenital heart defect without living to see their child; shortly thereafter, Dambeck-Keller, now pregnant and a widow, was bombed out of their home.

She returned to her hometown of Göppingen, where, in October 1943—in the midst of the chaos of war—she gave birth to her son, Walter. Shortly thereafter she opened her Studio for Artistic Weaving Patterns, a hand-weaving studio with two looms and one employee. After Germany’s collapse, her high-quality fabrics were in great demand, especially among the American occupying forces. Additionally, she worked as an independent pattern consultant at the large weaving mill in Wendlingen for the mail order company Otto. Her sudden death in 1952 cut short a life that was finally on the upswing; she was looking forward to working with Max Bill to establish the School of Design in nearby Ulm and even awaiting the small car she had ordered from the German car manufacturer Gutbrod.