Born: Charlotte Beese, January 28, 1903, Reisicht, Germany (now Rokitki, Poland)

Died: November 18, 1988, Krimpen aan den Ijssel, Netherlands

Matriculated: 1928

Locations: Germany, Poland, Austria, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), Soviet Union, Netherlands

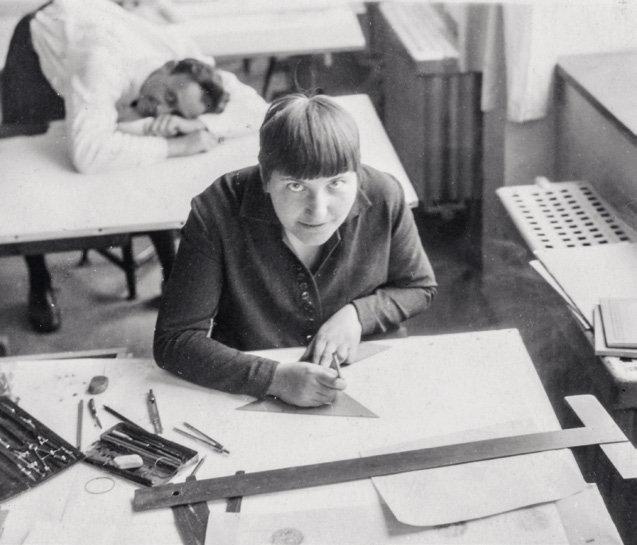

The Bauhaus’s architecture program was undoubtedly male-dominated, but this didn’t mean that no women were interested. In 1928, the first woman enrolled in this new workshop at the Dessau Bauhaus: Charlotte Beese. After passing her high school exam (Abitur), she left her Silesian hometown of Reisicht (today Rokitki, in Poland) at the age of eighteen to train as a craftswoman, first to the Breslau Academy of Fine and Applied Arts, where she studied drawing, and then to the German Workshops (Deutsche Werkstätte) in Hellerau, near Dresden. There Beese, a proficient stenographer and typist, was hired as an office worker, but she also learned the basics of weaving in the textile workshop. The Werkstätte had had links with the Bauhaus since its Weimar period, and in 1926—after hearing enthusiastic reports from Bauhaus alumni—Beese (after a long illness) applied and was accepted to study in Dessau.

Following Josef Albers’s preliminary course (Vorkurs) and classes with Wassily Kandinsky and Joost Schmidt, Beese initially applied to the weaving workshop under Gunta Stölzl before she was accepted to the architecture program. As a student of Hannes Meyer, she developed a passion for his “new theory of building” and immersed herself in statics, building material theory, construction, heat engineering, and city planning. She took part in Meyer’s showcase project, the Trade Union School (Allgemeiner Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, ADGB) in Bernau near Berlin, and was particularly impressed by his social-humanistic maxim: “People’s needs instead of luxury needs.” A personal relationship also developed between Beese and Meyer, who was fourteen years her senior—an affair that not even the otherwise tolerant institution could condone. A husband and father of two, Meyer feared for his position and convinced his lover to leave the school in the spring of 1929 to work on the ADGB construction project in his Berlin office. But this did not go well, and she could not easily find other employment. Her application to Otto Haesler’s architecture firm in Celle, for example, was rejected by former Bauhaus student Walter Tralau because he “did not like to work with ladies.”

However, she succeeded with the progressive social economist Otto Neurath and learned to design graphics for his pictorial statistics—later referred to as “Isotype”—at his newly opened Museum of Society and Economy in Vienna (Gesellschafts-und Wirtschaftsmuseum). Meyer did not allow her return to the Bauhaus, though she would have been useful in teaching the architecture classes. Instead, she transferred first to Hugo Häring’s architecture firm in Berlin and then to the Czech city of Brno, where she was a design architect for Bohuslav Fuchs’s modern, large-scale projects. It was only after Meyer was dismissed from the Bauhaus and relocated to Moscow that the couple reunited. However, their attempt to live as romantic and professional partners failed; out of work and pregnant with their son, Peter, who would be born in 1931, she returned to Brno, where she joined the Czech Communist Party and the Left Front (Levá Fronta) cultural organization. After a brief detention, she no longer felt safe and decided to return to a socialist country, this time the Ukraine. There, in the city of Kharkiv, she took part in the prestigious workers’-city building project around a new tractor factory.

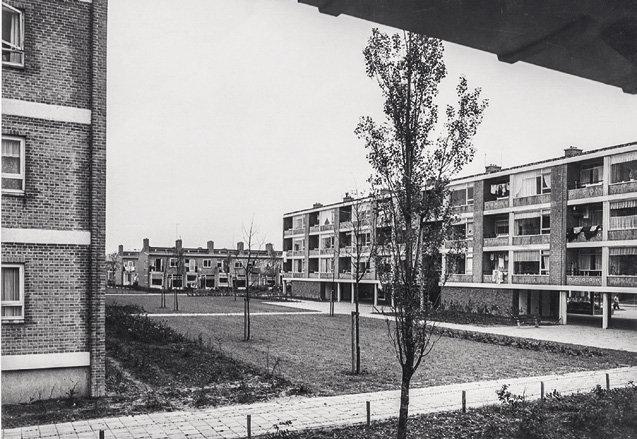

Lotte Stam-Beese (architect), play street with gallery building, Pendrecht, 1963

In Kharkiv, she met the Dutch architect Mart Stam—whom she knew already from his Bauhaus guest lectures—when he came to the Soviet Union with the “May Brigade,” led by Ernst May, the former head of the Municipal Planning and Building Control Office in Frankfurt and of the “New Frankfurt” project. An intense partnership developed between them, which led to Beese joining the brigade and to her working on the city of Orsk’s reconstruction in Orenburg Oblast. In 1934, she returned with Stam to the Netherlands, where they founded the firm Stam en Beese Architecten in Amsterdam; she was primarily in charge of interior architecture, photography, and advertising art. Like Stam, she joined the progressive architects’ association de 8 and contributed articles to its publication, de 8 en opbouw (the 8 and building). By then, she and Stam were married and they welcomed their daughter Ariane in 1935; after Stam had an affair, they divorced in 1943.

In 1940, however, Stam-Beese had returned to study architecture at the Academy of Architecture (Voortgezet en Hooger Bouwkunst Onderwijs, VHBO) in Amsterdam and finally earned an official degree. She received her diploma in 1945 and became a city planner and architect for the Department of Urban Development in Rotterdam for twenty-two years. The first woman to hold this office—and a German at that—she helped rebuild the downtown areas, which had been destroyed by her countrymen during the war. In particular, she dedicated herself to social housing. In 1955, she was promoted to lead architect and, in 1969, one year after retiring, was appointed Knight of the Order of Orange-Nassau (The Netherlands). Her Bauhaus education, and the hardship she had experienced in the Soviet Union, influenced her throughout her life, and she remained committed to fair and socially responsible housing.