Born: June 1, 1904, Weimar, Germany

Died: May 8, 1933, Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Palestine (now Israel)

Employed: Teacher of gymnastics and sport for women at the Bauhaus, Dessau, 1928–1932

Locations: Germany, Palestine

Karla Grosch embodied the “typical Bauhaus girl” like no other. In 1930, her smile graced the front page of an article in the popular illustrated weekly newspaper Die Woche about the Bauhaus as an educational establishment especially for “girls who want to learn something.” Curiously, this was specifically not the case for Grosch: she was one of the few young women who had come to the Bauhaus not to study but to work, in her case as a physical-education and gymnastics teacher. Describing herself, she once said: “The ambition to accomplish something significant myself was, unfortunately, something I absolutely did not possess.” Compared to her fellow Bauhaus members, Grosch’s life would take a more tragic turn, and she would not live to see her thirtieth birthday. Carrying her unborn child in her womb, she would drown while swimming off the coast of Palestine in the spring of 1933.

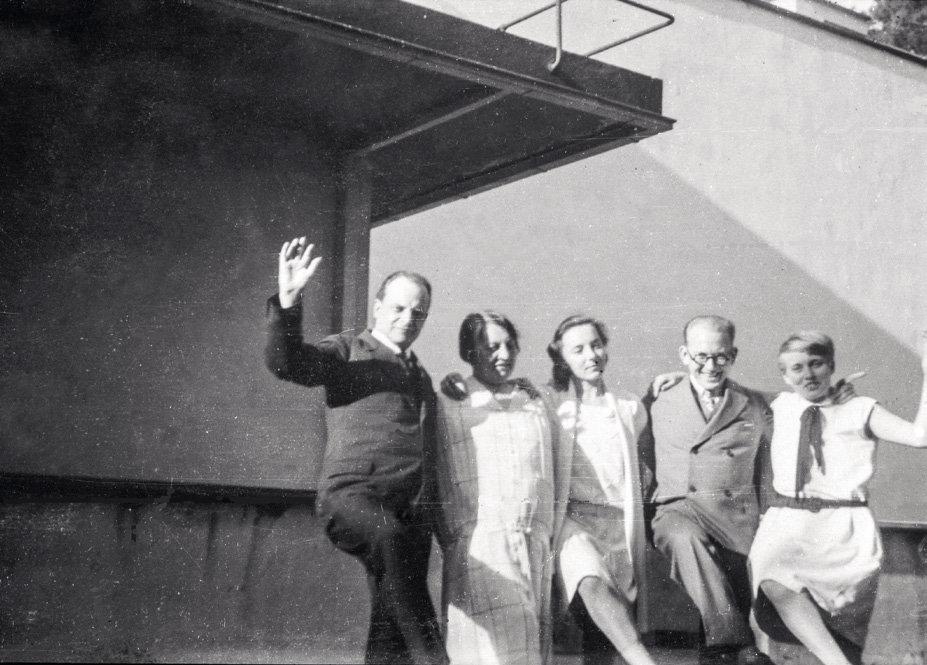

Karla Grosch was born in Weimar in 1904; yet, although she grew up in the birthplace of the Staatliches Bauhaus, she was not interested in a fine-arts education. Instead, she left to study in Dresden, where, as one of the first female students of Gret Palucca—nearly her contemporary in age—she was instructed in one of the most important dance forms of the time. A student of Mary Wigman, Palucca gave considerable impetus to expressionist dance, started her own studio in 1925, and was highly renowned among the Bauhaus masters. As early as 1926, Kandinsky praised her work in two essays and printed a picture of her mid-leap in his book Punkt und Linie zu Fläche (Point and Line to Plane); the following year, Moholy-Nagy waxed lyrical upon seeing her performing at the Bauhaus Dessau. A photograph by Felix Klee from this April 1927 guest performance has been preserved; it shows Felix, Paul and Lily Klee posing with Palucca and Grosch, who had accompanied her.

Group photograph on the occasion of the Palucca performance at the Bauhaus. From left to right: Paul and Lily Klee, Gret Palucca, Herbert Trantow, Karla Grosch. Photograph by Felix Klee, 1927

It is therefore no surprise that, in searching for someone to supervise sport and gymnastics classes, the Bauhaus chose this student of Palucca’s who was already familiar with the institution and its educational approach, and who enjoyed her own physicality to the fullest. “I derive a childlike pleasure from the way I have control over my body, how I can challenge it, how it yields, works, and I can completely lose myself in its capabilities,” she once wrote. Grosch started work in the spring semester of 1928, at precisely the time that Walter Gropius left the Bauhaus. It can be assumed, however, that Grosch’s hiring had still been decided under his guidance; having such instruction at the Bauhaus was a tradition that dated to the school’s founding, particularly Gertrud Grunow’s dance-oriented, rhythmic education based on her Harmonisierungslehre (theory of harmonization). A decade later, things had changed significantly: in fitness-obsessed Weimar society, physical training took center stage. The same was true for Grosch’s classes, which shifted the focus to the gymnastics component. This is illustrated in a series of photographs shot on the Dessau Bauhaus’s roof by T. Lux Feininger in 1930 showing classical gymnastics exercises and the lesson’s emphasis on athleticism. The students in the pictures are exclusively women; this was intentionally single-sex sport instruction.

Women’s gymnastics with Karla Grosch on the roof of the Dessau Bauhaus, 1930. Photograph by T. Lux Feininger

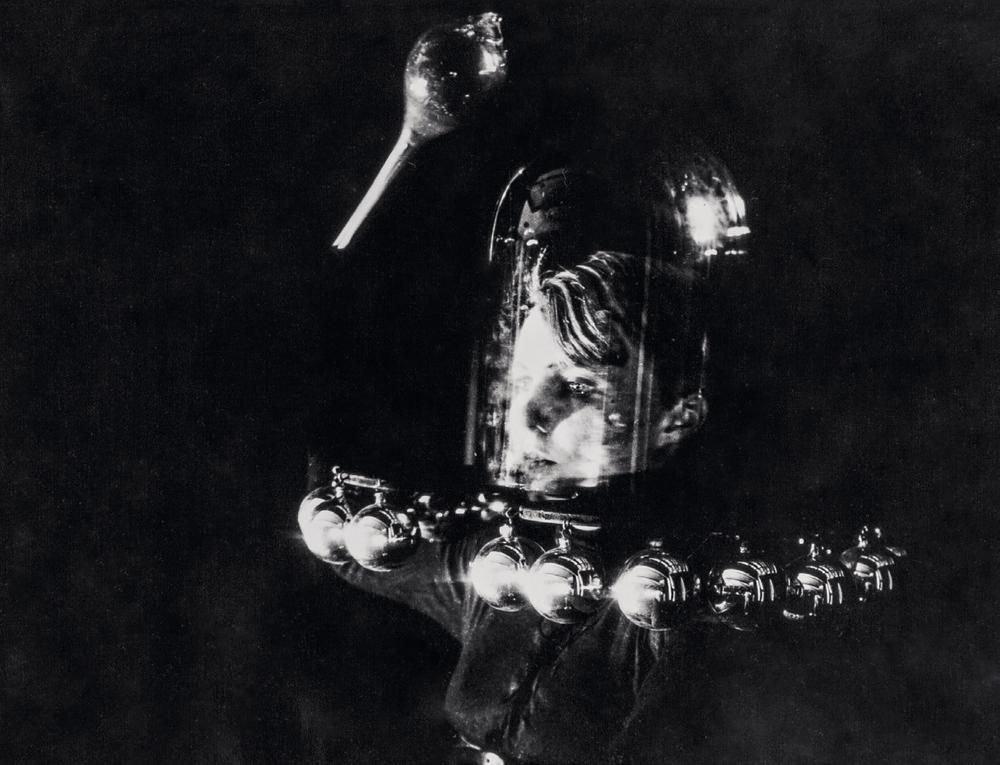

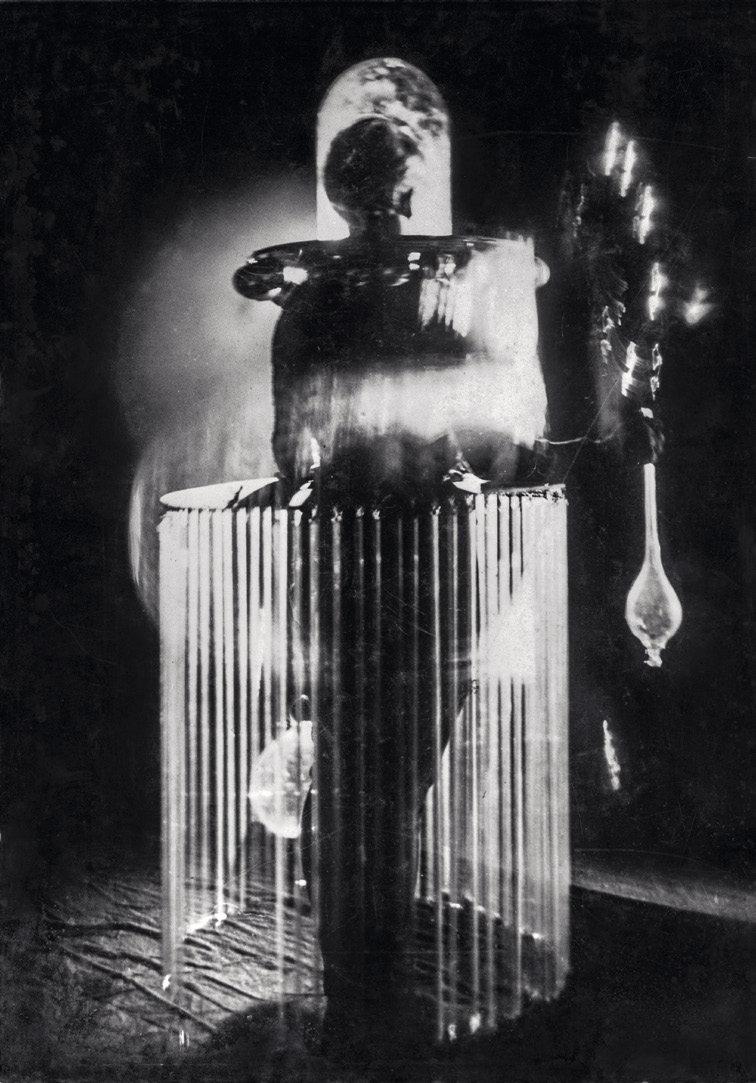

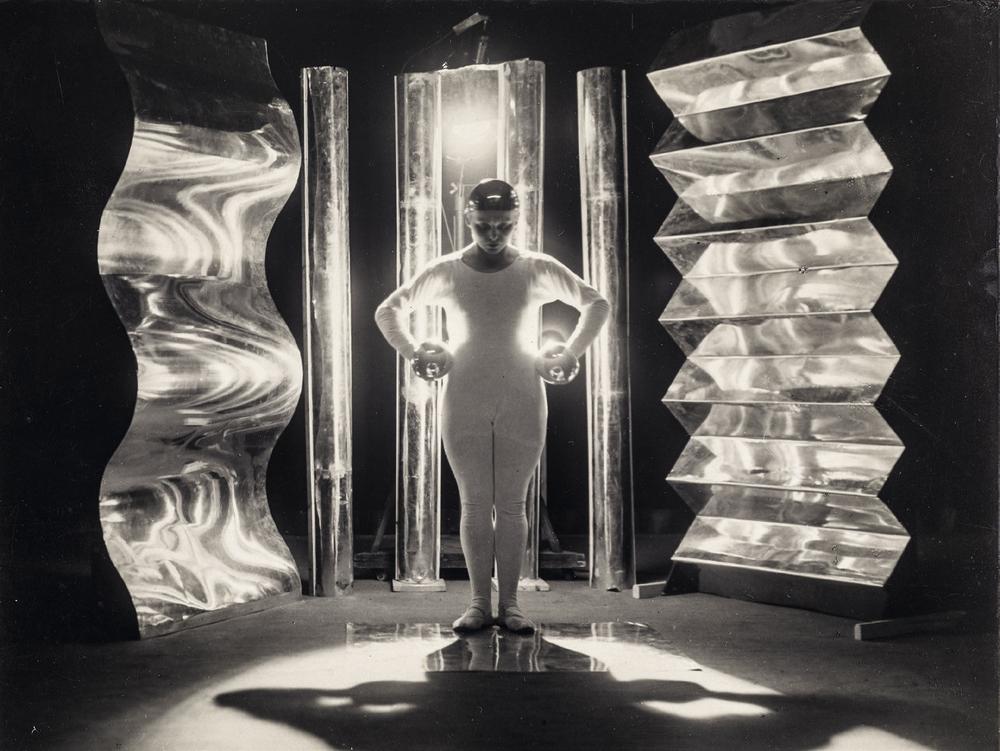

Grosch, however—who, along with the weaver Gunta Stölzl and Marianne Brandt in the metal workshop, was one of the Bauhaus’s few female instructors at the time—was also involved in the dance performances put on by the theater class. Prominent examples of this include her acting in the Materialtänze (Material Dances) by Oskar Schlemmer, which premiered in a guest performance at Berlin’s Volksbühne theater in 1929. Grosch participated in the interpretive pieces Metal Dance and Glass Dance, for which she donned a steely, shiny costume in the former and, in the latter, squeezed her head into a transparent globe. The piece’s futuristic set of reflective elements and dramatic lighting design meld together with Grosch’s body into a New Objectivity inflected representation of technological progress. In a 1929 issue of the Bauhaus’s journal published in honor of Schlemmer’s departure, he selected two of these photographs to show the ideal embodiment of the Tänzermensch (Dancer Being). With her professionalism—in which, as a trained dancer, she was far ahead of the average Bauhaus student—Grosch was unquestionably a valuable member of the stage ensemble. While just how much she was responsible not only for realizing Schlemmer’s vision but also for contributing choreography herself is unclear today, her involvement in it is almost certain.

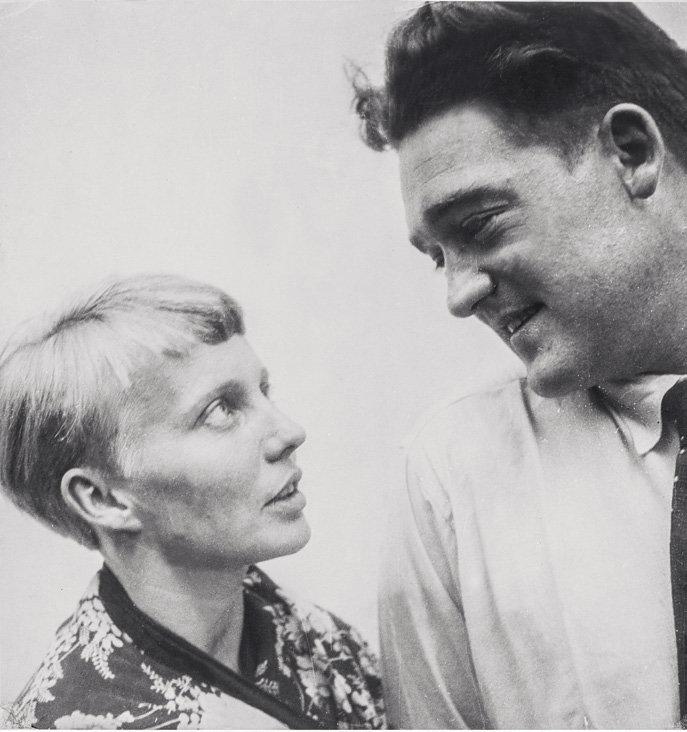

During her time at the Bauhaus, where she was employed until 1932, she also appears on the list of students in Walter Peterhans’s photography class, despite the fact that there is no evidence that she was ever active as a photographer (though she did own a personal camera for snapshots). She was, however, a popular photographic subject: with her youthful and dynamic charisma, fashionable short haircut, and toned physique, she embodied the beauty standards of the time and was well suited to serve as a visual role model for youthful Bauhaus members. In doing so, she stood for a specific type of the period’s “New Woman”—the successful career woman who made her own living and was not reliant on starting a family in order to be provided for.

“I derive a childlike pleasure from the way I have control over my body, how I can challenge it, how it yields, works, and I can completely lose myself in its capabilities.”

Karla Grosch

And yet, she longed for a partner and a child, once writing in a letter that this was “all that is still left to fulfill in my life.” She had a particularly tight bond with the Klee family, who even gave the young sports instructor a room in their Dessau Master’s House from 1928 to 1930. Lily accepted Grosch as a daughter; Paul showed great affection for her cat, Bimbo; and she was romantically involved with their son, Felix, for a period of time. She vacationed with the family, who even wanted to adopt Grosch after she was orphaned with her mother’s sudden death in 1931. Even after the Klees left Dessau, their affectionate relationship with Grosch remained unchanged. In addition to this, she shared an intimate relationship with Max Werner Lenz, the leading member of the company at the Friedrich Theater Dessau and seventeen years her senior. Numerous letters have been preserved that leave no doubt about the couple’s emotional closeness; in one, Grosch writes: “There is something wonderful about us—or is it from you and I get to share in it—in any case: there’s something wonderful about us.” Even Lily and Paul Klee welcomed Lenz into their hearts. They were avid theatergoers and, according to their son Felix’s recollections, were particularly fond of the Friedrich Theater, where Lenz rose to become senior director and bore full artistic responsibility for the theater’s acting division. As for Lenz, he was as deeply moved by Paul Klee’s art as he was by Lily Klee’s warmth, and they remained in close contact even after Lenz and Grosch separated.

Karla Grosch in glass mask by Oskar Schlemmer, 1929. Photograph by T. Lux Feininger

In letters to Lenz, Lily Klee later described the young dance teacher as a “friendly shining star,” “an enchanting, jovial person; a fully formed individual, equipped with deep emotion,” who was particularly able to give and experience love and joy. She was “full of charm and goodness; clever; rich with artistic talent; endowed with a reliable, honest character; so tactful; full of joie de vivre; full of radiant cheerfulness.” For Karla Grosch, Lenz became a close confidant, with whom she even shared her weltschmerz (world pain) when she was “no longer interested in living.” In Lenz, she found understanding and comfort, which allowed her to finally access the self-confidence and strength that others so admired in her. “Your love holds me, carries me through a lot in fulfilled peace. In this way, we’re necessary to one another, and I’m thankful for your presence as you are for mine. We can keep helping one another.” However, in spite of Lenz’s unreserved affection, for Grosch, it remained an “intellectual, virgin love,” as she was unable to completely open herself to him; tenderness made her uneasy, and in the spring of 1931, their relationship ended. “Yes, Lenzli, I never said that I loved you … Our souls are linked, but we have bodies too; we can’t deny them; they’re one.” She told him about her ongoing love for a man with whom she once wanted to have a child—a man who let her down. A passage in Grosch’s letter dated December 14, 1930 explains her indecisiveness in relation to the older man’s advances:

Karla Grosch, Glass Dance, 1929. Photograph by T. Lux Feininger

[I discovered myself] as a woman, terribly late in life. I found eroticism extremely unnecessary, and then it was always tied to the thought of a child, and no one impressed me that much. Unfortunately, or rather, thank God, I knew nothing of the usual dance-school perversities; I was too normal for such things and just let my development take its own course—sometimes I found myself a bit ridiculous when people didn’t want to believe that I was still so far removed from such things, but I knew they would come for me, too. And when the experience finally came over me, I didn’t think it could get any better—and yet it reached clearer and clearer heights, where you feel like you’re about to dissolve. Now it might be a fear of disappointment that keeps me closed off. I tell myself that it’s ridiculous to keep holding on to a fading ghost, but, whenever I think about it, it comes roaring back and becomes the present. And I can’t separate it from the person.

“It was as though our friendship was meant to reach one more highpoint before it drowned in the sea.”

Lily Klee

Grosch hurt Lenz with her candor. In an unsent letter to her, Lenz struggled with the realization that, apparently, his “physical sexual power is not enough to awaken a woman’s readiness for love.”

Ultimately Grosch entered into a relationship with the Austrian Bauhaus student Franz Josef “Boby” Aichinger, who—five years younger than Grosch (and twenty-two years younger than Lenz)—began studying in Dessau in the fall of 1931. Just a few months later, Grosch was introduced to his family and the two were already ringing in the New Year in his parents’ home; as for Boby, he was also well-liked by the Klees. Nineteen-thirty-two saw the closing of the Bauhaus and an increase in the political radicalization of the German nation, a development Grosch noted in, among other things, the influence of the Nazis on the Friedrich theater. Consequently, Grosch, who was of Jewish descent, and the architecture student Aichinger decided early on to immigrate to Palestine, where the construction of Tel Aviv also offered professional opportunities. They planned to marry in their new home and build a life together. In April 1933, Grosch, finally pregnant with the child she had always longed for, met with the Klee family in Dessau one last time before her departure. Paul took Bimbo the cat back to Bern, and Lily later wrote: “It was as though our friendship was meant to reach one more highpoint before it drowned in the sea.”

Karla Grosch, Metal Dance c. 1929. Photograph by T. Lux Feininger

The couple embarked on April 26, and soon after, on May 8, Karla Grosch went into cardiac arrest while swimming off the coast of Tel Aviv. A wave had torn her away; Aichinger held onto her so she could be loaded into a rescue boat, where a doctor administered two injections to her heart—to no avail. The by-then unconscious Aichinger, came to on the beach only to learn of his partner’s death. Grosch was buried the following day at the German cemetery in Sarona, near Tel Aviv. The bereaved speculated that Grosch would have survived the accident had she not been pregnant. Aichinger immediately returned to Germany, where he met Grosch’s sister, Paula Dora Lina, or “Ju,” who was now completely on her own. The two later married and lived in the Grosch’s family home in Weimar for several years before moving to Aichinger’s native Austria.