Born: 1906, Zagreb, Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Croatia)

Died: 1988, Zagreb, Yugoslavia

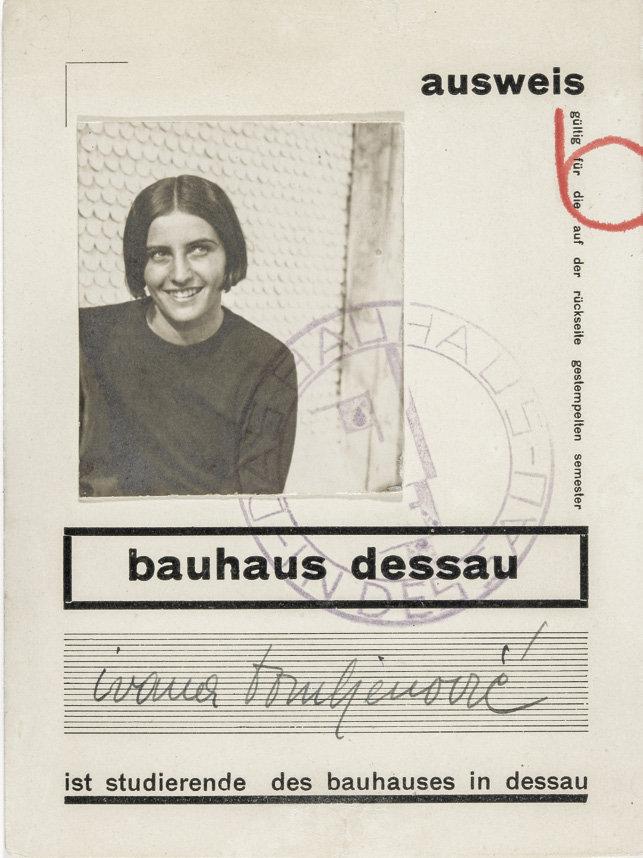

Matriculated: 1929

Locations: Yugoslavia (now Croatia), Germany, France, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic)

Bauhäusler, fashion plate, sports champion, rich girl turned revolutionary, and spy, the life of Yugoslavian artist and photographer Ivana Tomljenović reads like a juicy novel. She was creative, athletic, beautiful, and seemingly fearless. Tomljenović attended the Bauhaus from 1929 to 1930 and there found a place to explore new visual technologies and, over time, methods of pairing her art with her deepening commitment to communist politics. In turn, Tomljenović gave the later Bauhaus an embodiment of its ideal, a bold and radicalized new womanhood. Tomljenović’s Bauhaus photographs picture a seemingly carefree collective, but that collective was increasingly caught up in dramatic events outside of the school, resulting from the 1929 global financial crisis and ensuing renewed financial instability, and the concurrent political polarization both to the left and the right. It is against this economic and political backdrop that Tomljenović’s Bauhaus work—extraordinary in both its spiritedness and its overt political content—is best understood. She captured a Bauhaus dancing on the edge of the abyss. Among her experiments, one is completely unique within the school: the only film of the Dessau Bauhaus that was ever made.

Like many Bauhaus students, Tomljenović completed substantial if more traditional training prior to her arrival in Dessau. In 1924, she enrolled to study drawing and painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in her native Zagreb and received a cum laude diploma in 1928. She spent the next year in Vienna at the School of Arts and Crafts, where she studied metal design with famed designer Josef Hoffmann of The Vienna Workshops (Die Wiener Werkstätte). Meanwhile, Tomljenović had already broken records as an athlete famed for her prowess in sports including hazena (Czech handball), track and field, skiing, and basketball, becoming a darling of the 1920s sports press.

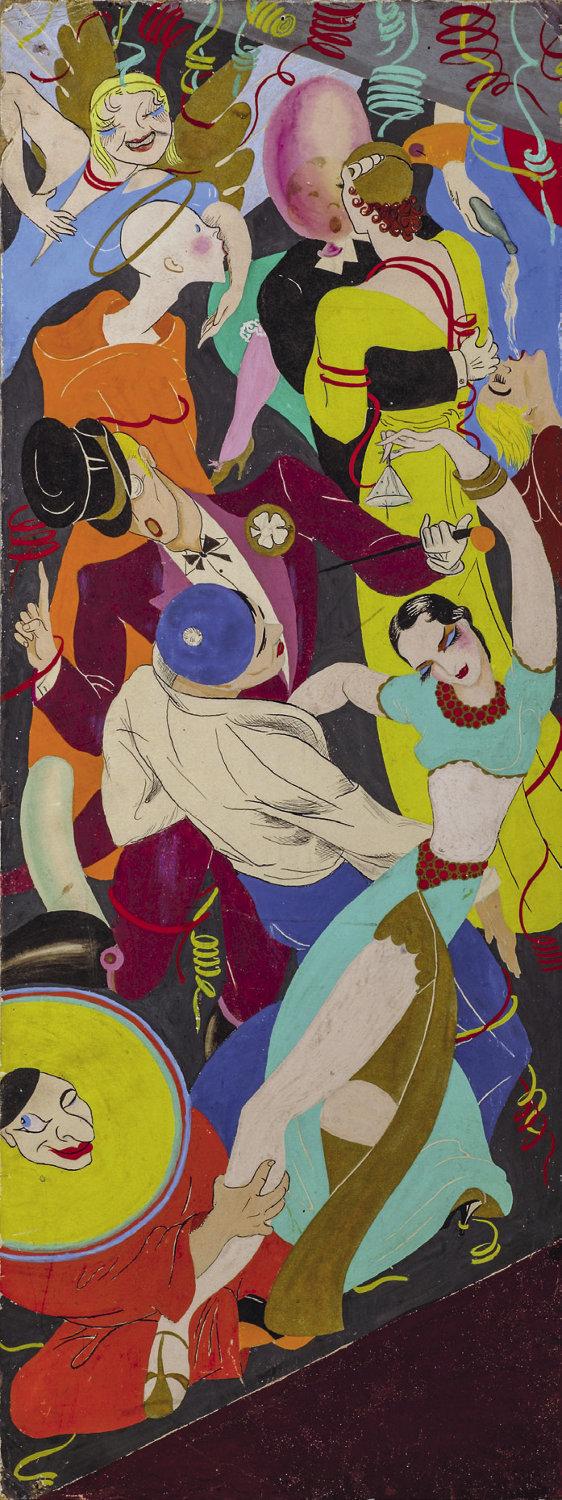

After attending a lecture by the Bauhaus’s charismatic second leader, Hannes Meyer, she dropped her Viennese studies and headed directly for Dessau. She arrived late in October of 1929—coincidentally during the global stock market crash—at a Bauhaus that was as thrillingly open as it was politicized. Through her prior training, Tomljenović had acquired considerable skill in painting and color theory as well as an eye for madcap fashion, as is evident in her painting of intertwined figures in Student Party, likely made during her first semester. The work’s narrow format provides a compressed space for outrageously costumed students, one of whom wears an egg helmet reminiscent of designs from Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus stage; another, a scantily clad, dark-haired beauty, has the markings of a self-portrait.

Ivana Tomljenović, Students’ Party at Bauhaus, 1929–1930

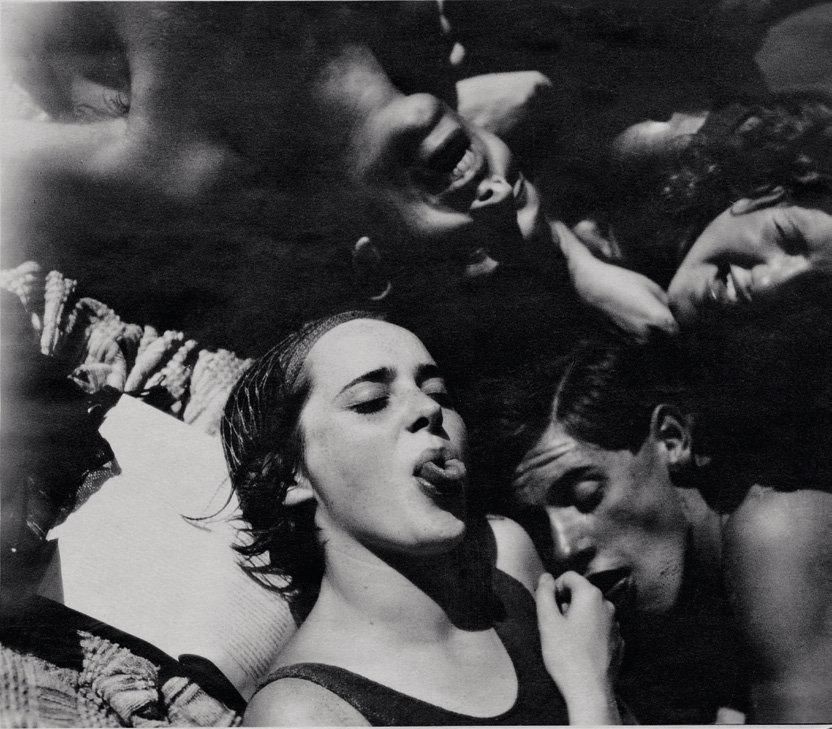

During her first semester she studied with Josef Albers in the preliminary course (Vorkurs) and the famed Wassily Kandinsky. Tomljenović passed the Vorkurs and was accepted for advanced studies in the photography workshop of Walter Peterhans. Peterhans was strict and emphasized technical perfection in photography. Yet he also encouraged experimentation in a number of ways, and Tomljenović deployed these approaches as she captured the camaraderie of Bauhaus life. A shot from 1930 pictures her fellow Bauhaus students shot from above, sunbathing with books cast aside. They flirt, make faces, and laugh heartily for the camera but also amongst themselves; they are fully in the moment of the photograph.

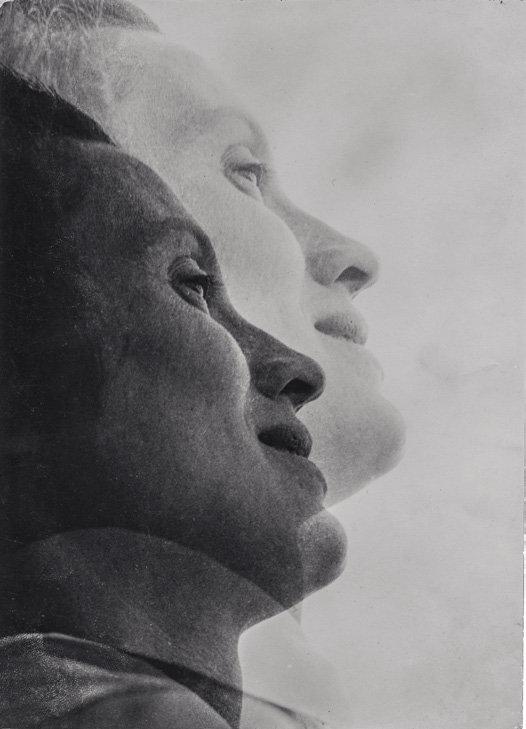

Flavored with an insider’s view on 1920s new womanhood, Tomljenović’s photographs of her fellow female Bauhäusler are particularly subtle and show diverse forms of modern femininity. In some of these, Tomljenović used experimental printing techniques, including collaging and photomontage, as in her portrait series of Margit Mengl, the Bauhaus secretary, romantic partner of Hannes Meyer, and mother of his son. In her role as secretary, it was Mengel who had signed Tomljenović’s student ID card in the fall of 1929. Tomljenović used the photographs she took of Mengel in the spring of 1930 as the basis for experiments in the printing process. These are formal exercises, but the compositions lend their subject an iconic dignity and pensive interiority. Like Tomljenović, Mengel was ideologically committed to revolution; along with other former Bauhaus members, she would join the so-called “Bauhaus Brigade” formed by Meyer to immigrate to the Soviet Union in the fall of 1930.

Ivana Tomljenović, Bauhaus Students, Dessau, 1930

Ivana Tomljenović, photomontaged portrait of Margit Mengl, 1930

Tomljenović’s uniting of Bauhaus life and new media came to its fullest fruition in her untitled film, dubbed “Bauhaus in 57 Seconds” by scholar Bojana Pejić. Long forgotten, the film came to light in the 1980s, yet, despite its being the only film of the Dessau Bauhaus building and students, it has largely been ignored, with a few notable exceptions. She shot it with a 9.5-millimeter Pathé Baby camera, an inexpensive format created in the early 1920s for amateur filmmakers and home viewing. While she was not an experienced filmmaker, Tomljenović was well versed in avant-garde film, and in June of 1930, the Bauhaus hosted Hans Richter for a screening of his and others’ films. Tomljenović later recalled that she and the other students were sharply critical of his work and accused him of being a right-winger; he pulled out his Communist Party booklet to prove his membership. Her film’s sequences were created not through editing but rather by simple, sequential shooting, with the film stock left in the camera between takes. The result is a film that races by, a jumble of raucously diverse images of Bauhaus members and unidentified figures in motion interacting with the Bauhaus building and the camerawoman. Sequences show fellow Bauhäusler including building-construction instructor Alcar Rudelt, weavers Grete Reichardt and Kitty van der Mijll Dekker, and metal designer Otto Rittweger; others take the Bauhaus building and life as characters themselves with pans across the Prellerhaus (the student dormitory) wing, of coffee and sandwiches on the canteen’s terrace, like any number of Bauhaus photographs come to life. While the film has no “story” per se, Tomljenović’s last shot is the word “Ende,” a surrealist nod to narrative films of the day.

Ivana Tomljenović, stills from an untitled Bauhaus film, c. 57 seconds, 1930

Tomljenović became a card-carrying communist at the Bauhaus with papers under an assumed name, Wirinea Hölz. Her pro-worker politics were a rejection of her upbringing in a family that drew their substantial wealth from banking and coal mines, and which moved in Yugoslav society’s upper-most echelons; Tomljenović had been a fifteen-year-old bridesmaid at King Alexander I’s wedding in 1922. Fully radicalized at the Bauhaus, she sought methods to visualize her new politics in both technique and subject matter. She photographed communist celebrations on May 1, 1930, International Workers Day; made portraits of individual workers; and pictured the communist writer Ernst Toller on his visit to the school to speak with the students about revolution.

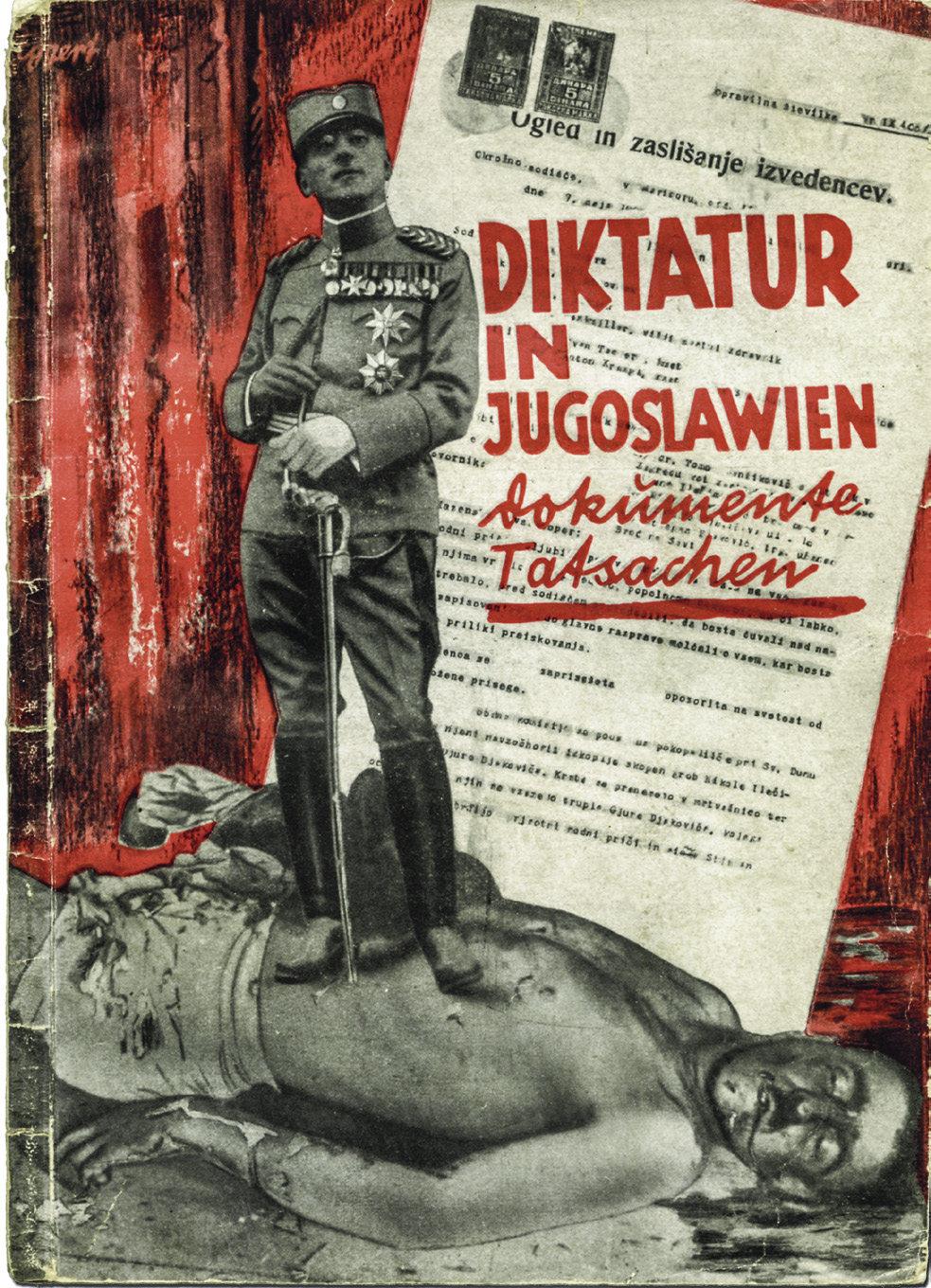

Tomljenović frequently visited Berlin where her circles included Yugoslavian exiles from the dictatorship of King Alexander I, which had begun in January of 1929. In 1930, she attended an exhibition titled Diktatur in Jugoslawien: Dokumente, Tatsachen (Dictatorship in Yugoslavia: Documents, Facts), where she was asked by one of the founders of the Yugoslavian Communist Party to create a photomontage cover for the exhibition’s catalogue. The image she created is in the spirit of Dadaist and communist John Heartfield, whom she met in Berlin in the fall of 1930 if not before, but whose book-cover design circulated widely, especially in communist circles. Tomljenović’s montage shows the clueless and cruel king posing cheerfully in his medal-covered uniform while standing on the body of a dead revolutionary, surrounded by blood red. Another hand added the exhibition’s title, and Tomljenović’s name was not included in the publication, likely for her own safety.

Ivana Tomljenović, photomontage for brochure cover, Diktatur in Jugoslawien (Dictatorship in Yugoslavia), 1930

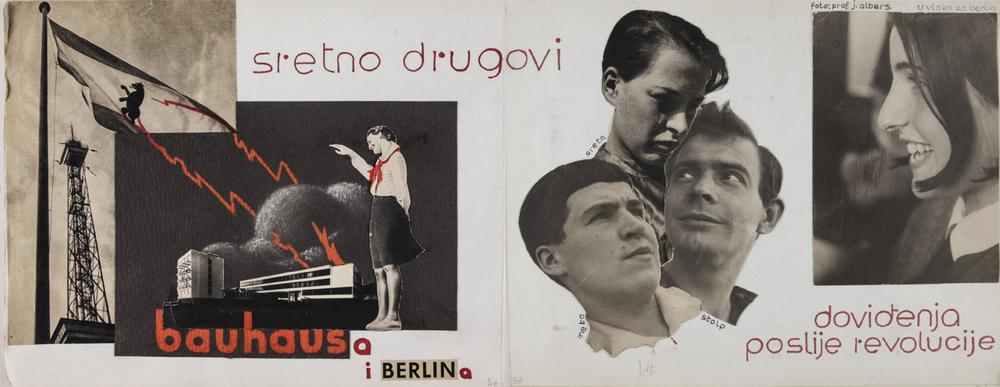

Rising tensions between right and left-wing factions in both the Bauhaus and the city of Dessau led to the expulsion of Tomljenović’s close friend Naftali Rubenstein (later Naftali Avnon), in May of 1930, followed soon by a number of other communist students. When the city’s mayor fired Hannes Meyer in midsummer, Tomljenović decided that it was time to go. Later in her life, she assembled an album of her photographs and photomontages including a double-page photomontage from 1930. A seeming celebration of her leave-taking, it is titled, Good Luck, Bauhaus and Berlin Comrades, and See You after the Revolution. From the left, red letters read Sretno drugovi (“good luck comrades” in Croatian) with “Bauhaus” and “Berlin” collaged in beneath. But “bauhaus” has turned red, a rewriting of it as a communist institution. Tomljenović uses the power of photomontage to blow up the school: electric red lightning bolts jolt down on the Bauhaus as it is engulfed in black clouds. These originate in Berlin, symbolized by its bear mascot and iconic radio tower. Tomljenović herself looms over the building as a grinning oversized Young Pioneer who seems to welcome the lightning strike on her alma mater. Photographed heads of three of her friends appear next to the word drugovi, as if labeled “comrades,” in the center of the collage: Grete Krebs and Kurt and Meta Stolp. At the right is a photograph of Tomljenović in profile by Albers, hair bobbed and bursting with pluck. She has labeled it “on the train to Berlin” and captioned it with biting glee: “See you after the Revolution.”

Uprooted from the Bauhaus, Tomljenović went to Berlin along with most of her friends; she worked as a graphic designer and on set design for communist theater director Erwin Piscator, alongside Heartfield. On the side, she played Czech handball for SC Charlottenburg and won the European championship with her team. In 1931 she left for Paris ostensibly to study literature at the Sorbonne, but her main occupation was as a communist operative. The following year, Tomljenović moved on to cosmopolitan Prague, where she continued her work as a graphic designer and married Alfred Meller in 1933. Together they created sophisticated window displays for department stores, with electric lights and ingenious moving elements; some were interactive with viewers. These displays so captivated the public that police officers had to keep the public at bay.

Ivana Tomljenović, Good Luck, Bauhaus and Berlin Comrades, and See You After the Revolution, c. 1930

Prematurely widowed in the summer of 1934, she moved to Belgrade and continued work in graphic design and teaching. In 1938, she returned to Zagreb, the city that would become the capital of the Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia in 1941. She survived the war and worked as an art teacher, first at a girls’ high school and then at a teacher-training institute. Curators and scholars in Zagreb rediscovered Tomljenović and her work in 1983, and she was the subject of several exhibitions and publications during the last five years of her life. Bringing the work of Ivana Tomljenović, a communist new woman, back to its rightful place in Bauhaus history reveals an array of thrilling visual experiments that picture a new unity that was at the heart of the Dessau Bauhaus’s later years: that of art and politics.