Born: Ricarda Meltzer, January 30, 1912, Göttingen, Germany

Died: July 29, 1999, Jerusalem, Israel

Matriculated: 1930

Locations: Germany, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), Hungary, Israel, Greece

The joy that Ricarda Schwerin gave so many children with her wooden toys eluded her in much of her own life. After her mother’s untimely death in 1915, Ricarda, then just three-years-old, grew up in a children’s home so as not to hinder her father’s career. When one of her teachers became her stepmother, she was passed around from aunt to aunt, and finally to her grandparents in the Saxon city of Zittau until her grandfather died. She then returned to live with her father and stepmother, but it was hardly a success; she refused Protestant confirmation, causing a scandal, and was again sent away.

Ricarda, born Meltzer, then attended boarding school in Königsfeld in the Black Forest along with Meret Oppenheim—who would later become an avant-garde artist and a close friend. Taking pictures with a small box camera became Meltzer’s favorite pastime. Intrigued by the brochure—“Young people, come to the Bauhaus!”—she applied to the Dessau Bauhaus without her family’s knowledge shortly before her final school exam. The portfolio of her work samples was impressive, and, to her own surprise, she was accepted. She was even more astonished that her father was willing to pay for her Bauhaus studies—perhaps in part because it would keep her away from the family home.

Meltzer enrolled at the Bauhaus for the 1930 summer semester where she witnessed the last few official acts of director Hannes Meyer. On her first day, she swapped her long blond braids for the short bob favored by young women at the Bauhaus and became a popular photographic subject for her school friends. The contrast between her boarding school’s rigid daily routine and the unrestrained Bauhaus way of life could not have been more stark, and, since she found little enjoyment in the “fine art” by Kandinsky or Klee, she quickly decided to concentrate on photography and Walter Peterhans’s classes. Meltzer was also impressed by the advertising workshop, as she recalled decades later in an autobiographical sketch: “The new clear forms that were created in the workshops inspired me immensely… I found the innovative use of the space of a page in a lay-out, the possibilities of giving a text a whole new effect through printing, tremendous.”

Although Ricarda herself said that during her time at the Bauhaus she debated enough for a whole lifetime, it was her admiration for Heinz Schwerin, rather than her philosophical discussions that prompted her to join the communist student organization KoStuFra. It was love at first sight, even though she initially thought the Jewish architecture student, a “show-off.” When Schwerin helped organize the protest against the then director of the Bauhaus, Mies van der Rohe, in the spring of 1932, Meltzer was also barred from attending classes and later, from the school. Subsequently, the couple lived briefly in Berlin, where Meltzer worked in Ellen Auerbach and Grete Stern’s studio, ringl + pit. Meltzer then studied with Fritz Wichert at the Frankfurt School of Free and Applied Art (Städelschule), but this also ended abruptly when the Nazis assumed power. Schwerin had remained politically active, and was arrested in April 1933 for illegally distributing flyers, but managed to flee. As a Jewish and communist former Bauhäusler charged with resistance and high treason, he had no choice but exile. Meltzer, not directly threatened herself, accompanied him to Prague and the Giant Mountains region, where, for three months, she photo-documented traces of torture on the bodies of escapees from German concentration camps. Meltzer and Schwerin were married in Pécs, Hungary, in May 1935 with Ernst Mittag and Etel Mittag-Fodor, old friends from Dessau, as witnesses. That summer, the newlyweds obtained a tourist visa for Palestine and joined the community of former Bauhaus members there.

As with many exiles, the Schwerins at first found it hard to find work and a means to live. A home-made advertising flyer preserved in the family estate shows a touching example of the simple means through which they sought to get ahead. Together with his former school friend Selman Selmanagic, Schwerin offered “structural and civil engineering, shop fitting, interior decoration, [and] garden facilities” in the most modern style, at the cheapest prices, with an unlikely specialty in flowerboxes (“Spezialitaet: Ia Blumenkaesten”). Ricarda Schwerin, in turn, presented herself like this: “You need photos? Visit my studio. You will be satisfied.” The postscript stating that customers should make advanced appointments because of high demand was likely only a subtle advertising tactic.

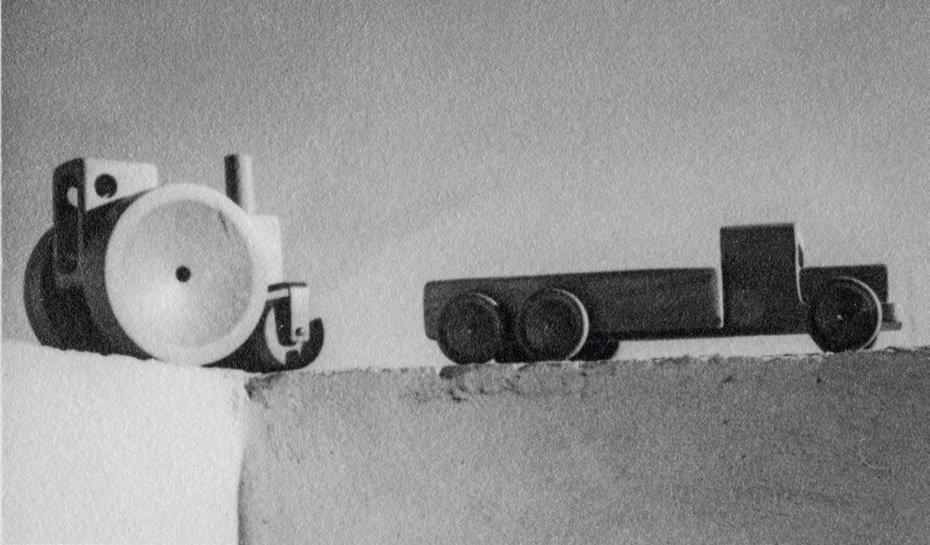

Lorry and steamroller, handmade wooden toys, c. 1940

It was the couple’s workshop for applied arts—Schwerin Wooden Toys—that first brought them modest success. They produced solid wooden toys that were even exhibited in the Palestinian pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair in 1937. An early review came from art historian Karl Schwarz, the founder in 1933 and, briefly, director of the Jewish Museum in Berlin; after his emigration, Schwarz headed up the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. In “Erziehung zur Kunst” (“Education for Art”) in the daily newspaper Ha’aretz, Schwarz wrote:

Until now, we had no toy worthy of being called a “real toy.” But a few days ago, I saw several playthings in Jerusalem that aroused my enthusiasm. Simple wooden toys, sturdy and with a particularly attractive and artistic form. I gave them to several children to play with and they took them with great enthusiasm and did not want to let them go … Two young artists in Jerusalem, Mr. and Mrs. Schwerin, make these things with a sense of form and pedagogical understanding. The Schwerins start with a basic shape, avoid all complication, suppress all embellishment, and thus true artists’ works emerge through simple and natural means.

This application of Bauhaus thinking—already valued in the Weimar Bauhaus’s wood workshops—to children’s toys ensured the Schwerins’ livelihood and allowed them to start a family: their daughter, Jutta, and son, Tom, were born in 1941 and 1945, respectively. However, this modest happiness would soon end, when, after Palestine’s division, Heinz was drafted into the Haganah, the precursor to the Israeli Army, and died during deployment in January 1948; possibly due to a brain tumor, he lost his balance and fell from the roof of a three-story building. Although Ricarda had never converted to Judaism, she decided to remain in Israel to care for her parents-in-law. As a single mother she could not run the workshop alone, so after various attempts to make a living, she opened a private daycare to support her family.

Ricarda Schwerin as a photographer in Palestine. Photograph by Alfred Bernheim

In 1955 Schwerin met widowed photographer Alfred Bernheim, a Jerusalemite twenty-seven years her senior, who had studied under Walter Hege at the College of Architecture in Weimar. She returned to photography in his studio and for nearly twenty years, the two shared a fulfilling professional and personal relationship, in which she drew on her knowledge from the Bauhaus. The couple also became members of a German-speaking artists’ circle who met regularly in a coffeehouse. Important politicians in young Israel such as Martin Buber, Menachem Begin, and Yitzhak Rabin also had their portraits taken in Studio Bernheim, which was situated conveniently near the Knesset building, seat of the Israeli parliament. Schwerin took powerful portraits of Golda Meir and David Ben-Gurion, and a photo series with the renowned philosopher, Hannah Arendt, whom she had met during the trial of Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem; they became famous. Schwerin and Arendt struck up a friendship, and, as Arendt, wrote to her husband Heinrich Blücher: “Ricarda is very stubborn, and it would take weeks to straighten her out…. And lives there in Jerusalem, not destitute, but quite difficultly!! … [S]he can hardly speak Hebrew, thus lives mute!!” Upon the invitation of Blücher, an old friend from Prague, Schwerin traveled with Arendt and others to Greece; she was overwhelmed by the landscapes and ruins and captured them in numerous travel photographs that were praised by, among others, the philosopher Karl Jaspers.

Ricarda Schwerin, Hannah Arendt, Jerusalem, 1961

Ricarda Schwerin, Memories of the trip to Greece

“Ricarda is very stubborn, and it would take weeks to straighten her out…. And lives there in Jerusalem, not destitute, but quite difficultly!!”

Hannah Arendt

With Arendt and Blücher’s help, the first publication of Schwerin’s photographs was finally realized: in 1969, Jerusalem: Rock of Ages was published by New York’s Harcourt, Brace & World and simultaneously by London’s renowned publisher Hamish Hamilton. Schwerin’s daughter Jutta later published extensive family recollections and recounted that her mother was hurt because, although the book was a joint effort with her husband, her name was set in smaller type than that of Bernheim on the title page and was omitted entirely from the cover. Schwerin shared this fate with many female Bauhäusler, whose achievements in professional projects with their husbands and other male collaborators were often not adequately appreciated. She did, however, receive full recognition for her photo illustrations for two popular Israeli children’s books by Jemima Tschernowitz, one of the country’s most respected authors.

In 1974, Alfred Bernheim died, and Schwerin ran the photo studio business alone until her age forced her to give up. Yet at sixty-six, she retrained as a tour guide and, into the 1980s, led groups of German and English-speaking tourists around Jerusalem. She passed away three weeks after her first great-grandchild’s birth in 1999. In her correspondence with Jutta—who had left Israel in 1960, dedicated herself to social reform of the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1970s, and been elected to Parliament (Bundestag) as a Green Party politician—Ricarda Schwerin once wrote: “Nothing new. Liberal child-rearing, women’s liberation, women’s communes. It all already existed when I was at the Bauhaus.”