Born: 1910, Japan

Died: 2000, Japan

Matriculated: 1930

Locations: Japan, USA, Germany, UK, Netherlands, Italy

Arguably the most global Bauhaus woman was Michiko Yamawaki, who came to the school from Japan during a trip around the world with her husband, photographer and architect Iwao Yamawaki. They joined the Dessau Bauhaus in the fall of 1930 and stayed for its final two years under the directorship of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Together, the Yamawakis contributed Japanese ideas to the Bauhaus’s international atmosphere and would become principal translators of Bauhaus thinking in Japan upon their return. They brought with them not only two years of Bauhaus experience, but texts and objects by fellow Bauhäusler that they shared with artists, designers, and their students in Tokyo. Both Yamawakis became teachers at Tokyo’s New Architecture and Design College, informally known as the Japanese Bauhaus.

Michiko Yamawaki had little exposure to modern design or architecture prior to meeting her husband, but she was grounded in Japanese aesthetic traditions including the art of the tea ceremony, which she learned from her father, a master of it. From her first encounter with the Bauhaus, she intuited profound sympathies between it and Japanese aesthetic principles. She described these in her richly illustrated 1995 memoir, Bauhausu to Chanoyu (Bauhaus and Tea Ceremony), which unfortunately is only available in Japanese: “The functionality of the tools for tea ceremony is similar to Bauhaus functionality, where all unnecessary things are pruned. Some elements that remain after eliminating all possible waste are in harmony with each other and have a presence that seems to have been there from the beginning.”

As a proper young woman from a wealthy family, at eighteen, Michiko Yamawaki completed girls’ high school and began traditional “bride training” in piano, cooking, and household management. Her first meetings with her future husband, Iwao Fujita, twelve years her senior, were arranged and chaperoned. In contrast to her sheltered upbringing and arranged introduction to Iwao, Michiko’s marriage to him would introduce her to the realm of modern architecture and design, and the two of them would venture out into the world together. And in one respect, she was unusual compared to other Bauhaus women: Michiko Yamawaki had but one name over the course of her lifetime. Chosen to succeed her uncle as head of their family branch, keeping her name was a condition of their marriage, so Iwao Fujita took her last name and became Iwao Yamawaki.

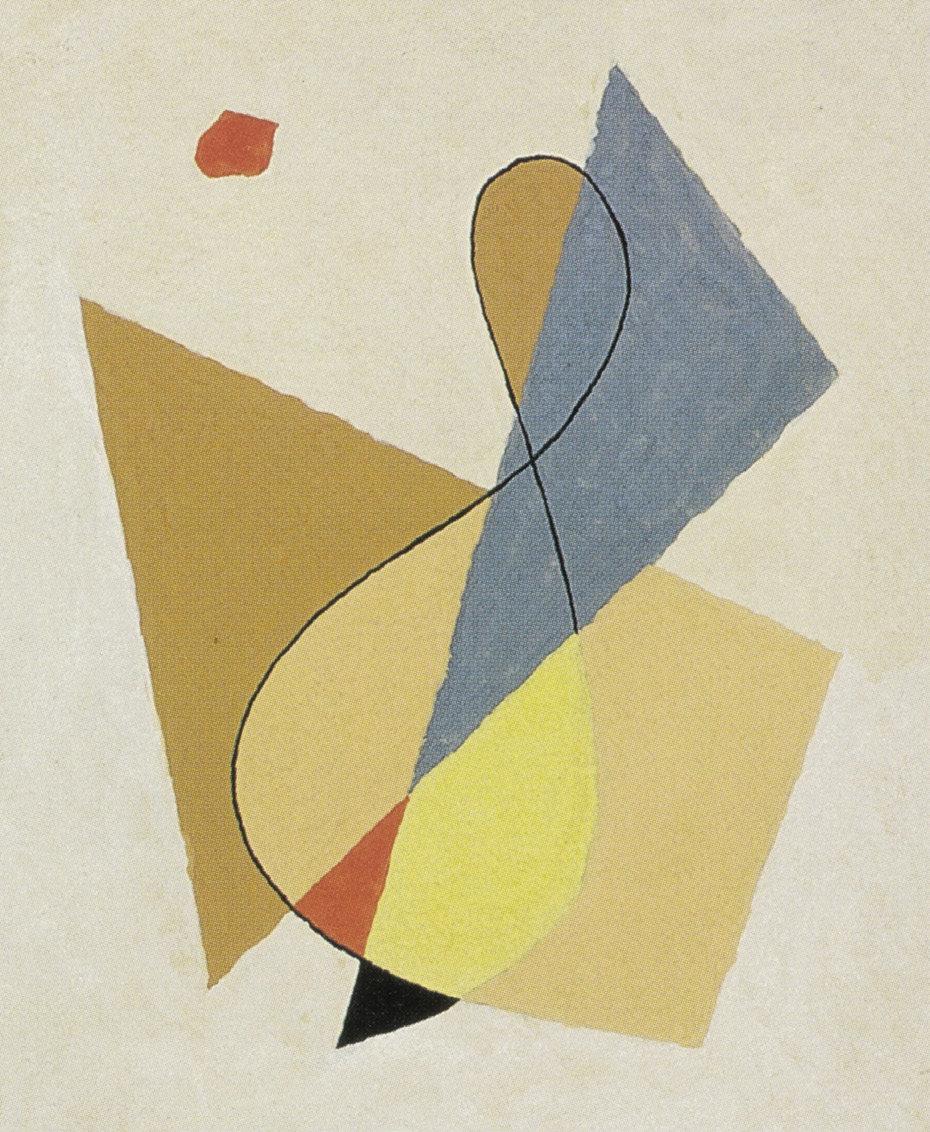

Michiko Yamawaki, study from analytical drawing with Wassily Kandinsky, 1930, subsequently published in 1933 August issue of Architecture Craft/Aishi Oru [I See All]

Michiko Yamawaki was just twenty when they left Japan in early May 1930, bound for Hawaii. They traveled to California and then across the United States of America to New York, where they lived for two months. Yamawaki bought Western-style clothes there and—against the express instructions of her mother—cut her long hair into a bob. They arrived in Berlin in July 1930 intent on attending the Bauhaus, which they knew by reputation. Iwao later recounted a Japanese craze for all things Bauhaus in the late 1920s, with young architects in Tokyo fighting over copies of László Moholy-Nagy’s Von Material zu Architektur (The New Vision: From Material to Architecture). Within a few days of Iwao Yamawaki’s September letter of application, he received an affirmative response instructing him to arrive in Dessau in mid October. Like many Bauhäusler, Iwao Yamawaki had completed his education prior to applying to the Bauhaus; he was a trained architect with work experience, and a self-taught photographer. By contrast, Michiko Yamawaki had no relevant experience. This may account for the fact that her notification of admission appeared as an afterthought in that same letter and did not even mention her by name: “We concurrently confirm to you herewith that, after consulting with the responsible gentlemen, your spouse has been accepted to the bauhaus basic course on a trial basis.” The photograph on Michiko Yamawaki’s student identity card, a stunning close-up taken by her husband, shows her as the embodiment of the “moga,” or Japanese Modern Girl. To aid Germans in pronouncing her name correctly, she wrote it as “Mityiko” while there.

Michiko Yamawaki quickly made her way at the Bauhaus. She completed the preliminary course (Vorkurs) with Josef Albers in one semester and later recalled his frequent praise of her work, both for her intuitive understanding of concepts and her dexterity with materials. That same semester, she took analytical drawing with Kandinsky and was particularly influenced by his ideas of tension (Spannung), as a 1930 drawing, later reproduced in a Japanese design magazine, shows. In March 1931, Mies van der Rohe wrote to Michiko Yamawaki directly of her unconditional acceptance into the weaving workshop. He also recommended that she work on her language skills “intensively,” since otherwise advanced study might prove difficult. Michiko Yamawaki later recalled the kindness of masters like Kandinsky, who often stayed after class with the couple to go over concepts from his lectures, sometimes in English, which they spoke better than German.

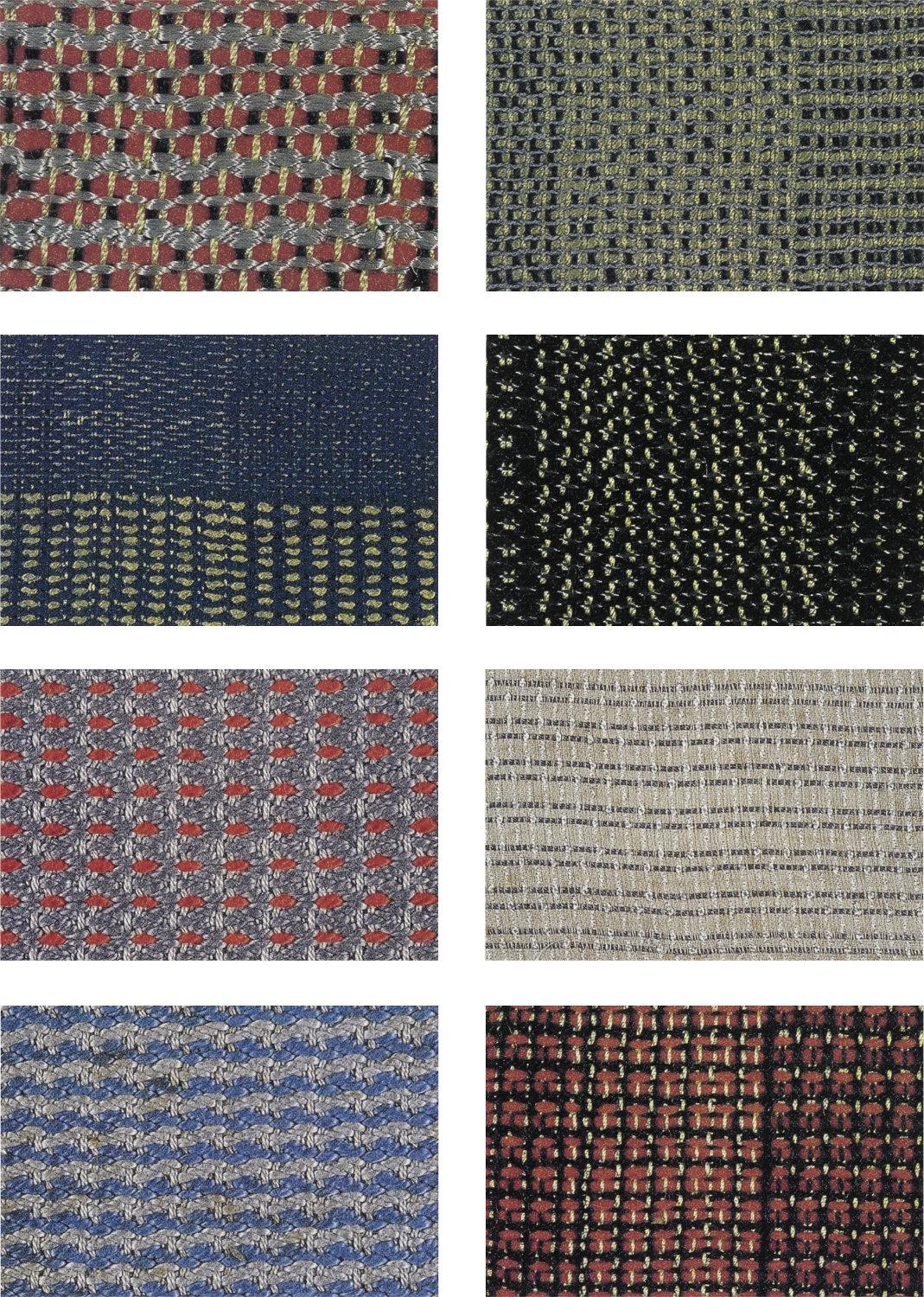

Michiko Yamawaki, weaving textile samples.

Top row: blanket, 1931

Second row: blanket, 1931

Third row: blanket, 1931 (left) and curtain, 1932 (right)

Bottom row: blanket, 1931 (left) and blanket, 1932 (right). This piece was woven as a full-size blanket and displayed at the end-of-semester exhibition.

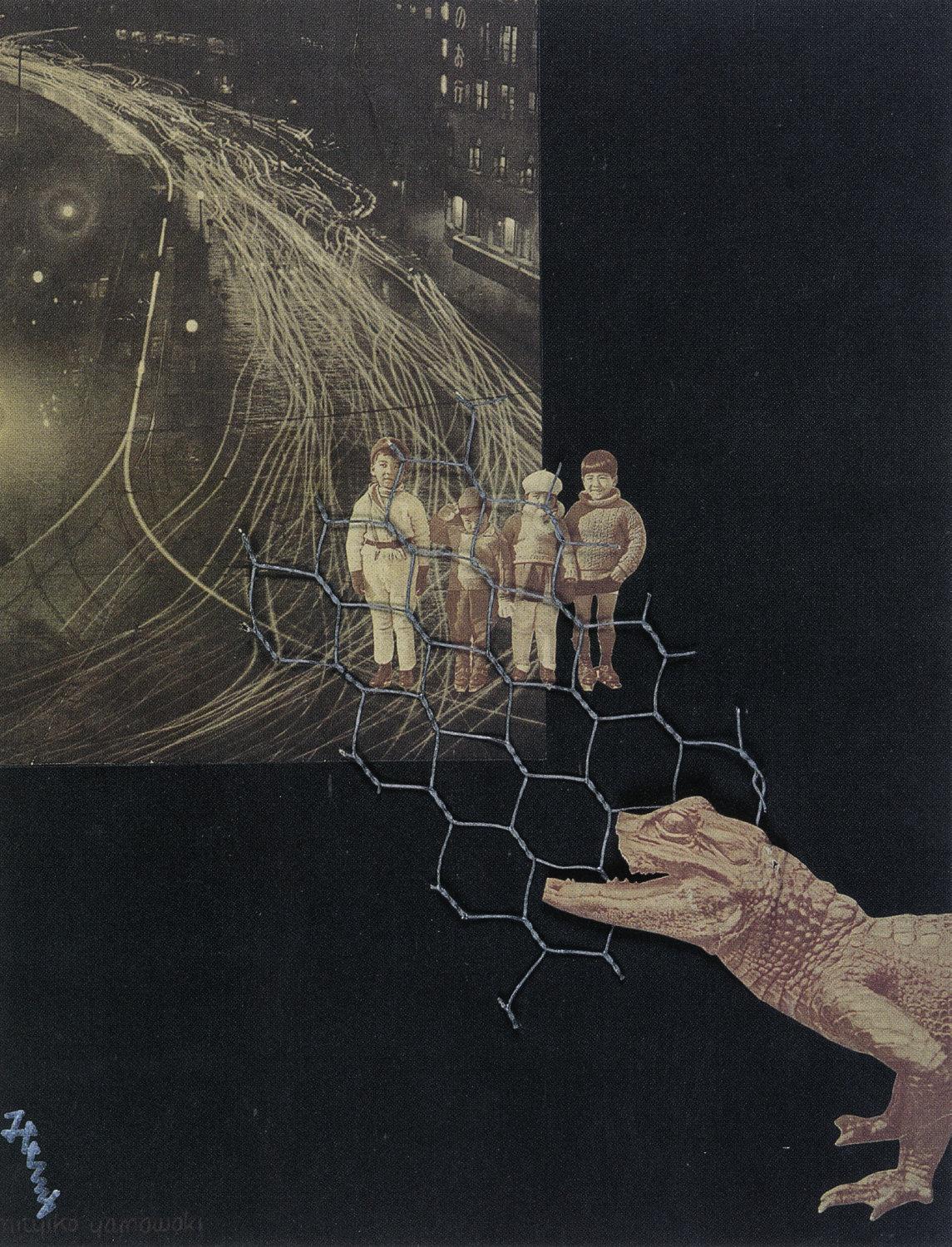

Michiko Yamawaki, design drawing for a decorative textile/wall-hanging, 1932

Once in the weaving workshop her schedule specified a six-day-per-week program, with between two and six hours in the workshop along with classes in drawing with Albers, free painting and a seminar with Kandinsky, and typography (Schrift) with Joost Schmidt. She also took a course in Gestalt psychology, which interrogates perception of objects and pictures, with Karlfried Graf von Dürckheim, who came from Leipzig to lecture during the 1930-1931 academic year. While Lilly Reich was head of weaving, Yamawaki’s primary teachers were Gunta Stölzl and Anni Albers. In part, her textile work was typical of this period at the Bauhaus, with its adventurous mixture of colors, stitches, and materials that included even strips of cellophane, and an orientation towards industrial production. Yet within the workshop, she was seen as distinctly Japanese in, for example, her color choices, which fellow workshop member Otti Berger positively remarked upon. Yamawaki created textile patterns and designs for abstract works including a colorful 1932 rug. She also made works in other media, such as a 1931 assemblage she displayed in an end-of-semester exhibition, A Safety Zone, a creepy blend of archaic and modern, danger and safety.

“Do not copy. You need to know yourself. The most important thing is to know the material.”

Michiko Yamawaki

In 1932, as the Bauhaus was forced to close and face an uncertain future in Berlin, the Yamawakis decided to return to Japan. They first traveled in England and the Netherlands, where they met De Stijl architect J.J.P. Oud, before departing from Naples on a ship for Japan via Sri Lanka and Hong Kong. In a November 1932 letter to the Yamawakis, Kandinsky expressed his and his wife’s gratitude for their parting gifts: “We always admire the tasteful and fine work of Japanese things.”

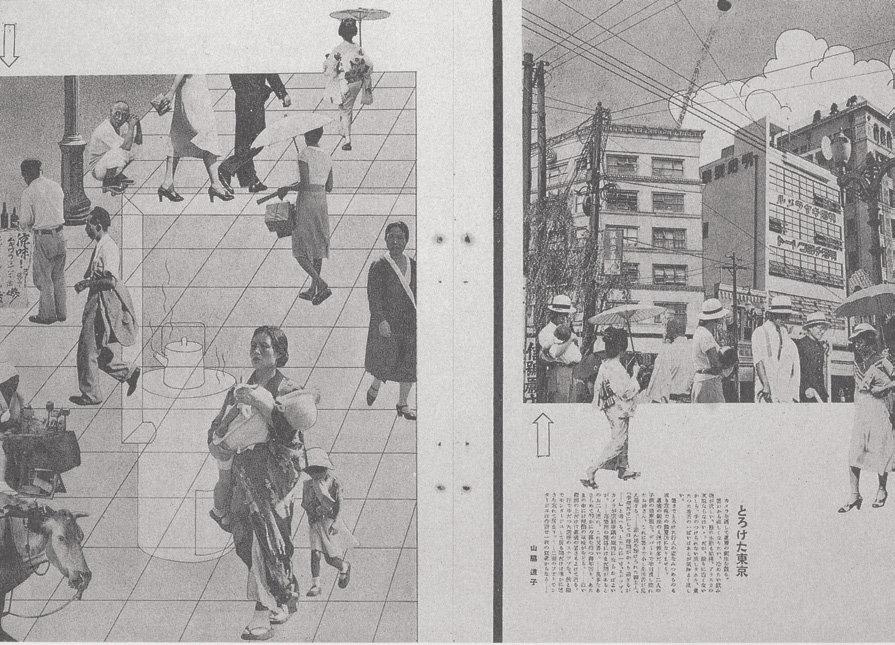

Back in Tokyo by the end of 1932, the Yamawakis settled into a two-floor apartment in the fashionable Ginza district; the upper one recreated aspects of the Bauhaus with books and objects that they had transported, including two looms, metal works by Marianne Brandt, textile samples by Otti Berger, and furniture by Marcel Breuer. Bauhaus texts they brought were quickly translated into Japanese by Renshichirō Kawakita for the curriculum of his recently founded New Architecture and Design College. Michiko worked in fashion as a model and designer; in 1933, she published Melted Tokyo in Asahi Camera magazine, a playful sampling of twenty-one photographs taken in the summer heat of Ginza to show urban dwellers’ traditional and modern approaches to dress. That same year, the Shiseido Gallery hosted an exhibition of Michiko Yamawaki’s hand-woven textiles contextualized in a display of Bauhaus objects and photographs. Kawakita invited the Yamawakis to teach at the school and added a weaving course to its curriculum at the start of 1934, headed by Michiko. Students used the “Michiko Handloom” of her invention; relatively compact, it still allowed for approximately twenty diverse patterns. But by late July 1934 she had already ceased teaching as she was expecting the first of her two children in the fall, and the weaving department was closed.

In the face of rising nationalism and militarism, the internationally minded New Architecture and Design College was forced to close by the Ministry of Education in 1939, a fate not unlike that of the Bauhaus. Over the years, both Yamawakis nonetheless continued their teaching, design work, and publications that transmitted Bauhaus history and concepts, and they hosted a number of prominent former Bauhaus members in Japan, including Gropius. After the war, Michiko Yamawaki taught at Showa Girls’ College and then at Nihon University, Japan. A core element of her teaching was those intuitive aesthetic and philosophical links between the Bauhaus and Japanese tradition. In a 1993 interview with design historian Akiko Shoji she advocated: “Do not copy. You need to know yourself.” But above all: “The most important thing is to know the material.” This idea of truth to materials was an old one in Japan; through Michiko Yamawaki’s work, it again gained currency under the banner of the Bauhaus.

Michiko Yamawaki, A Safety Zone, 1931