Born: Hilde Isay, January 17, 1905, Trier, Germany

Died: October 24, 1971, New York, USA

Joined: 1931

Locations: Germany, France, Austria, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), UK, USA

Photographer Hilde Hubbuch died without heirs in New York City in 1971. Her story and her work come in and out of focus over time, but the traces she left, first as an artist’s muse and then as an artist in her own right, reveal glimpses of a vibrant, intellectual, and unconventional woman who would become one of the Bauhaus’s most supreme portraitists. Her training as a photographer provided her with a professional livelihood on her flight from Nazi Germany, first to Vienna and then to New York City.

Hilde Isay was born January 17, 1905, in the German city of Trier, the only child of a Jewish family who had made their fortune in banking and the cloth trade. At the age of twenty, she left home to begin studies during the 1925–1926 winter semester at the regional art school, the Karlsruhe Academy. Her drawing professor was painter Karl Hubbuch, a leading light of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement. As fellow painter Georg Scholz later recounted it, Hilde Isay’s straight-laced father became concerned about her activities and hired a detective from the Argus Agency to follow her; he found her and her professor in a hotel room in Wiesbaden. At the start of 1928 they married under some pressure, but apparently happily at least at the start. They decorated their shared studio in part with Bauhaus tubular metal furniture, and he painted her as the epitome of emancipated new womanhood in works such as his 1929 Viermal Hilde (Hilde Four Times). Whether she photographed prior to meeting Karl is unclear, but certainly once they were together Hilde Hubbuch began experimenting with photography, alone and with her husband, as in their series of comic self-portraits shot in a large mirror. They used a medium-format camera that curator Karin Koschkar—whose research gives us the clearest view of Hilde Hubbuch’s life and work—has identified as a Zeiss-Ikon Cocarette I Lux 521/2, the latest in portable technology. Hilde Hubbuch also took photographs in Paris, likely on a trip with Karl during the early 1930s, as well as made pictures of their bohemian life together, including her husband’s penchant for nude models.

At the start of 1931 Hilde and Karl Hubbuch went to visit the school whose modern furniture designs they had purchased, the Bauhaus. Impressed, Hilde Hubbuch decided to enroll in the summer of 1931; she is listed as a guest student (Hospitant) in the photography workshop with additional classes in practical studies, artistic design, and typography. Already an experienced photographer, she learned quickly and attained the high technical standards that Peterhans demanded. A surrealistic materials study from 1931 or 1932 is in perfect focus across its significant depth of field. The composition’s lower half is filled with strewn and curling photographic prints and snippets—portraits, interiors, and street photographs likely taken by Hubbuch—a wooden egg nestled in amongst them. A stark upper half balances this tumult of images with a grasping plaster hand that strains towards the photographs but is itself trapped under a wire-mesh cloche. Slightly to the left of the composition’s center is a small portrait of Hubbuch herself in profile, stoic in the chaos.

Hilde Hubbuch, Untitled (Still Life with plaster hand, wire-mesh cloche, and photographs), 1931/1932

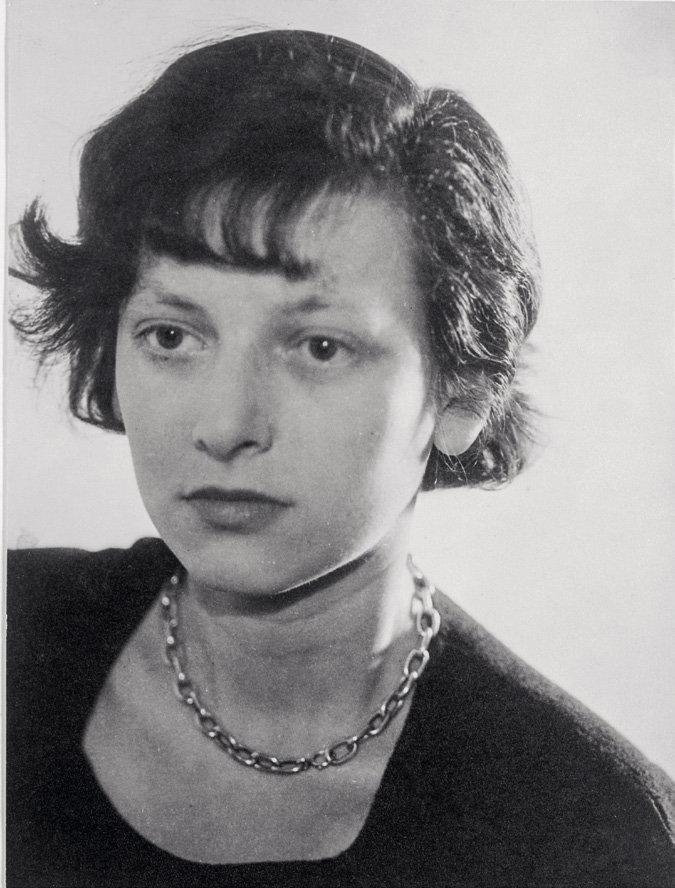

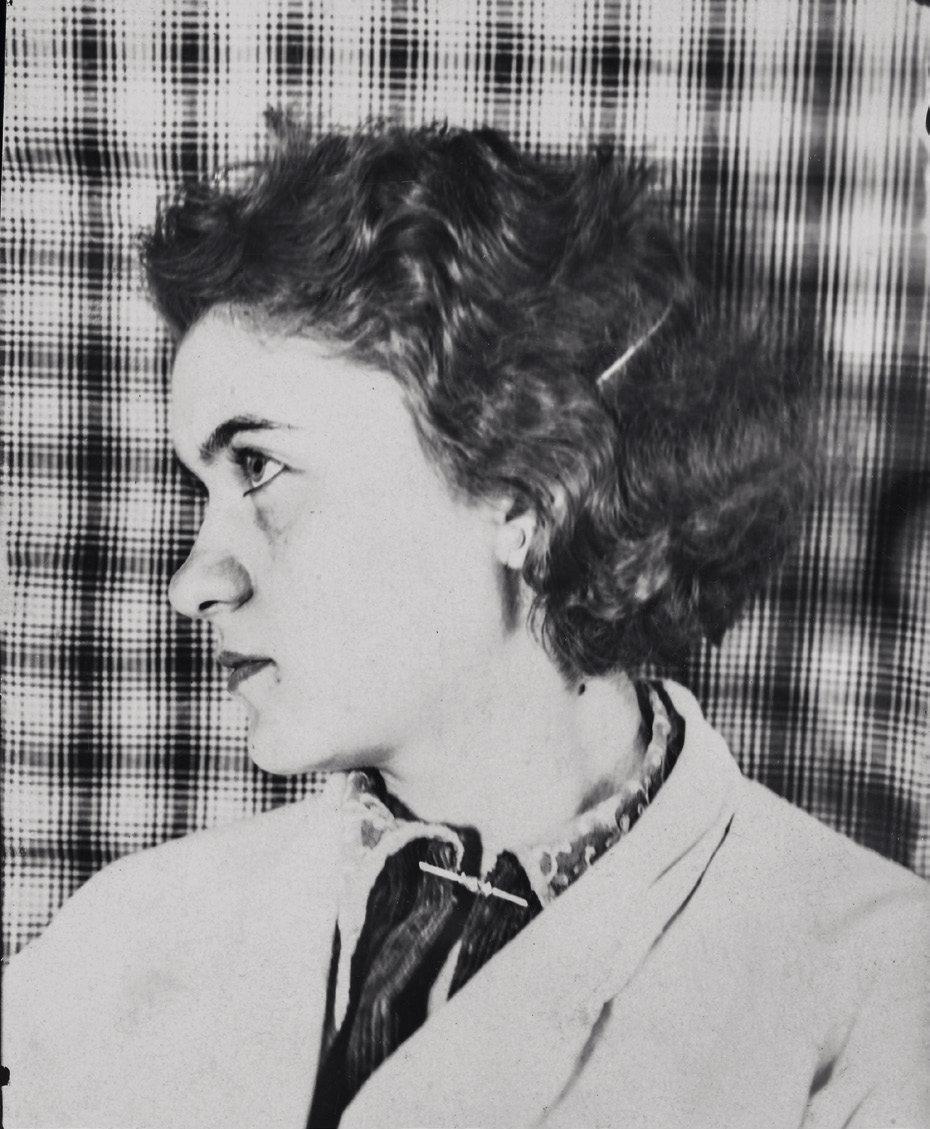

Hubbuch quickly developed as a technically proficient portraitist with a fresh take on faces and bodies; particularly noteworthy are her stunning images of modern women. One of these shows a pert yet serious Bauhäusler in stark profile against a patterned background—likely a shallow depth-of-field exercise for Peterhans’s classes. In another, her sitter appears both vulnerable in her scant evening wear and inaccessible in her private interiority. With her long skirt, loose chemise, and the sparkling beret crowning her short hair, she may be dressed for one of the famous outré Bauhaus parties. In different ways, these two women’s photographs manifest the new: the first in an almost defiant earnestness, the second distinctly in possession of her own sexual desirability. Hubbuch’s Bauhaus social circles were made up in part of politicized fellow photographers—women such as Irena Blühová. The two of them photographed each other; several extant portraits of Hubbuch by Blühová reveal her in different aspects. In the one made in 1932, Hubbuch has styled herself as a professional, perhaps in an image to include in a job application.

Hubbuch was apparently uninterested in attaining a degree at the Bauhaus; she seems to have maintained her visiting status and, according to photo-historian Jeannine Fiedler, in a roster from summer 1932, Peterhans marked her as having refused the exam. When the Dessau Bauhaus closed in October 1932, Hubbuch left to follow her mother to Vienna and obtained work as a photographer for the socially engaged Max Fau press agency. Throughout this period, Hilde Hubbuch had remained married to Karl, but their marriage was complicated, in part by his relationships with other women, and they divorced in 1935. It seems that they remained friends; in 1936 she sent a postcard to him from Prague, where she had gone by bus to take photographs of traditional Eastern European street scenes for the agency.

Hilde Hubbuch, Untitled, 1931 or 1932

In 1936, following the death of her mother and with Nazi sympathy growing in Austria, Hubbuch decided to leave Vienna for London, where her uncle lived. Little is known of her time there. In January of 1939, shortly before her thirty-fourth birthday, she sailed from Southampton for New York, where she gave her name to the authorities as “Hilde Hubbuck.” She appears in a US Census from April, 1940 as a renter in New York, head of her household, divorced, and a professional photographer. In a 1945 issue of the literary magazine The New Yorker, she advertised her services as “the Modern Approach to Child Photography.” Hubbuck was also a society portrait photographer; among her clients were the novelist Norman Mailer and William Shawn, The New Yorker’s editor for thirty-five years who was notoriously ill at ease with the public—photographers in particular. Hubbuck captured him in a 1952 photograph that shows him in a happily pensive moment, a testament to the trust she built with her subjects.

Hilde Hubbuck lived out her days in New York but returned to Europe several times and even visited Karl Hubbuch and his second wife, Ellen, in Karlsruhe in 1962, prior to her 1971 death at sixty-six. Her photos are held in the collections of the Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin, Los Angeles’s Getty Museum, and The Museum of Modern Art in New York. The last of these collections includes two touching photographs of Karla Grosch with her new husband Boby Aichinger (p.121), taken shortly before she too left Germany for Palestine and an untimely death.

Hilde Hubbuch, Untitled, c. 1931

Hilde Hubbuck, Portrait of William Shawn, 1952