Chapter 12

Autodesk® Maya®

Dynamics and Effects

Special effects animations simulate not only physical phenomena, such as smoke and fire, but also the natural movements of colliding bodies. Behind the latter type of animation is the Autodesk® Maya® dynamics engine, which is the sophisticated software that creates realistic-looking motion based on the principles of physics.

Another Maya animation tool, Paint Effects, can create dynamic fields of grass and flowers, a head full of hair, and other such systems in a matter of minutes. Maya also offers dynamic simulations for hair, fur, and cloth. In this chapter, I’ll cover the basics of dynamics in Maya and let you practice working with particles by making steam.

- Learning Outcomes: In this chapter, you will be able to

- Create rigid body dynamic objects and create forces to act upon them

- Keyframe animated passive rigid bodies to act on active rigid bodies

- Bake out simulations to keyframes and simplify animation curves

- Understand nParticle workflow

- Emit nParticles and have them move and render to simulate steam

- Draw Paint Effects strokes

- Create and manipulate an nCloth object (a.k.a. nMesh)

- Collide nMesh objects and add forces and dynamic constraints

- Cache your nDynamics to disk

- Customize the Maya interface

An Overview of Dynamics and Maya Nucleus

Dynamics is simulating motion by applying the principles of physics. Rather than assigning keyframes to objects to animate them, with Maya dynamics you assign physical characteristics that define how an object behaves in a simulated world. You create the objects as usual in Maya, and then you convert them to dynamic bodies. There are rigid bodies, which are solid objects, and soft bodies, which are malleable surfaces. Soft bodies won’t be covered in this book; however, I will go through nCloth dynamics later, which is a much more powerful way of creating soft surface dynamics.

Dynamic bodies are affected by external forces called fields, which exert a force on them to create motion. Fields can range from wind forces to gravity and can have their own specific effects on dynamic bodies.

In Maya, dynamic objects are categorized as bodies, particles, hair, and fluids. Dynamic bodies are created from geometric surfaces and are used for physical objects such as bouncing balls. Particles are points in space that have renderable properties and are used for numerous effects, such as fire and smoke. I’ll cover particle basics in the latter half of this chapter. Hair consists of curves that behave dynamically, such as strings. Fluids are, in essence, volumetric particles that can exhibit surface properties. You can use fluid dynamics for natural effects such as billowing clouds or plumes of smoke.

Nucleus is a more stable and interactive way of calculating dynamic simulations in Maya than its traditional dynamics engine. Nucleus speeds up the creation and increases the stability of some dynamic effects in Maya, including particle effects (nParticles) and cloth simulation (through nCloth).

I’ll introduce nParticles later in this chapter; however, soft bodies, nHair, nCloth, and fluid dynamics are advanced topics and won’t be covered in this book.

Rigid Bodies

Rigid bodies are solid objects, such as a pair of dice or a baseball, that move and rotate according to the dynamics applied. Fields and collisions affect the entire object and move it accordingly.

Creating Active and Passive Rigid Body Objects

Any surface geometry in Maya can be converted to a rigid body. After it’s converted, that surface can respond to the effects of fields and take part in collisions. Sounds like fun, eh?

The two types of rigid bodies are active and passive. An active rigid body is affected by collisions and fields. A passive rigid body isn’t affected by fields and remains still when it collides with another object. A passive rigid body is used as a surface against which active rigid bodies collide.

The best way to see how the two types of rigid bodies behave is to create some and animate them. In this section, you’ll do that in the classic animation exercise of a bouncing ball.

To create a bouncing ball using Maya rigid bodies, switch to the Dynamics menu and follow these steps:

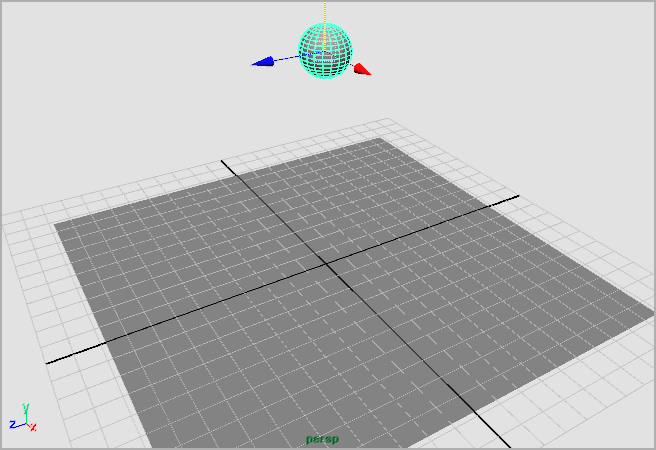

- Create a polygonal plane and scale it to be a ground surface.

- Create a poly sphere and position it a number of units above the

ground, as shown in Figure 12-1.

Figure 12-1: Place a poly sphere a few units above a poly plane ground surface.

- Make sure you’re in the Dynamics menu set (choose Dynamics from the Status line’s drop-down bar). Select the poly sphere and choose Soft/Rigid Bodies ⇒ Create Active Rigid Body. The sphere’s Translate and Rotate attributes turn yellow. There will be a dynamic input for those attributes, so you can’t set keyframes on any of them.

- Select the ground plane and choose Soft/Rigid Bodies ⇒ Create Passive Rigid Body. Doing so sets the poly plane as the floor. For this exercise, stick with the default settings and ignore the various creation options and Rigid Body attributes.

- To put the ball into motion, you need to create a field to affect it. Select the sphere and choose Fields ⇒ Gravity. By selecting the active rigid objects while you create the field, you connect that field to the objects automatically. Fields affect only the active rigid bodies to which they’re connected. If you hadn’t established this connection initially, you could still do so later, through the Dynamic Relationships Editor. You’ll find out more about this process later in this chapter.

To play back the simulation, set your frame range from 1 to at least 500. Go to frame 1 and click Play. Make sure you have the proper Playback Speed settings in your Preferences window; otherwise, the simulation won’t play properly.

When the simulation plays, you’ll notice that the sphere begins to fall after a few frames and collides with the ground plane, bouncing back up.

As an experiment, try turning the passive body plane into an active body using the following steps:

- Select the plane and open the Attribute Editor.

- In the rigidBody2 tab, select the Active check box. This switches the plane from a passive body to an active body.

- Play the simulation. The ball falls to hit the plane and knock it away. Because the plane is now an active body, it’s moved by collisions. But because it isn’t connected to the gravity field, it doesn’t fall with the ball.

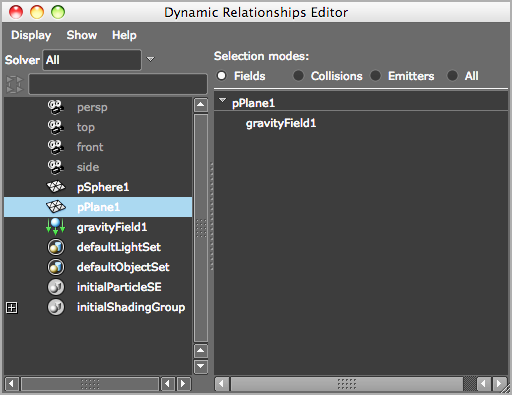

To connect the now-active body plane to the gravity field, open the Dynamic Relationships Editor window, shown in Figure 12-2 (choose Window ⇒ Relationship Editors ⇒ Dynamic Relationships).

Figure 12-2: The Dynamic Relationships Editor window

On the left is an Outliner list of the objects in your scene. On the right is a list from which you can choose a category of objects to list: Fields (default), Collisions, Emitters, or All. Select the geometry (pPlane1) on the left side and then connect it to the gravity field by selecting the gravityField1 node on the right.

When you connect the gravity field to the plane and run the simulation, you’ll see the plane fall away with the ball. Because the two fall at the same rate (the rate set by the single gravity field), they don’t collide. To disconnect the plane from the gravity field, deselect the gravity field in the right panel.

Turning the active body plane back to a passive floor is as simple as returning to frame 1, the beginning of the simulation, and clearing the Active attribute in the Attribute Editor. By turning the active body back to a passive body, you regain an immovable floor upon which the ball can collide and bounce.

Moving a Rigid Body

Because the Maya dynamics engine controls the movement of any active rigid bodies, you can’t set keyframes on their translation or rotation. With a passive object, however, you can set keyframes on translation and rotation as you can with any other Maya object. You also can easily keyframe an object to turn either active or passive. For instance, in the earlier bouncing ball example, you could animate the rotation of the passive body ground plane to roll the ball around on it.

Any movement that the passive body has through regular keyframe animation is translated into momentum, which is passed on to any active rigid bodies with which the passive body collides. Think of a baseball bat that strikes a baseball. The bat is a passive rigid body that you have keyframed to swing. The baseball is an active rigid body that is hit by (collides with) the bat as it swings. The momentum of the bat is transferred to the ball, and the ball is sent flying into the stadium stands. You’ll see an example of this in action in the next exercise.

Rigid Body Attributes

Here is a rundown of the more important attributes for both passive and active rigid bodies as they pertain to collisions:

- Mass Sets the relative mass of the rigid body. Set on active or passive rigid bodies, mass is a factor in how much momentum is transferred from one object to another. A more massive object pushes a less massive one with less effort and is itself less prone to movement when hit. Mass is relative, so if all rigid bodies have the same mass value, there is no difference in the simulation.

- Static and Dynamic Friction Sliders Set how much friction the rigid body has while at rest (static) and while in motion (dynamic). Friction specifies how much the object resists moving or being moved. A friction of 0 makes the rigid body move freely, as if on ice.

- Bounciness Specifies how resilient the body is upon collision. The higher the bounciness value, the more bounce the object has upon collision.

- Damping Creates a drag on the object in dynamic motion so that it slows down over time. The higher the damping, the more the body’s motion diminishes.

- Initial Velocity Gives the rigid body an initial push to move it in the corresponding axis.

- Initial Spin Gives the rigid body object an initial twist to start the rotation of the object in that axis.

- Impulse Position Gives the object a constant push in that axis. The effect is cumulative; the object will accelerate if the impulse isn’t turned off.

- Spin Impulse Rotates the object constantly in the desired axis. The spin will accelerate if the impulse isn’t turned off.

- Center of Mass (0,0,0) Places the center of the object’s mass at its pivot point, typically at its geometric center. This value offsets the center of mass, so the rigid body object behaves as if its center of balance is offset, like trick dice or a top-weighted ball.

Creating animation with rigid bodies is straightforward and can go a long way toward creating natural-looking motion for your scene. Integrating such animation into a final project can become fairly complicated, though, so it’s prudent to become familiar with the workings of rigid body dynamics before relying on that sort of workflow for an animated project.

Here are a few suggestions for scenes using rigid body dynamics:

- Bowling Lane The bowling ball is keyframed as a passive object until it hits the active rigid pins at the end of the lane. This scene is simple to create and manipulate.

- Dice Active rigid dice are thrown into a passive rigid craps table. This exercise challenges your dynamics abilities as well as your modeling skills if you create an accurate craps table.

- Game of Marbles This scene challenges your texturing and rendering abilities as well as your dynamics abilities as you animate marbles rolling into each other.

Rigid Body Dynamics: Shoot the Catapult!

Now for a fun exercise, you’ll use rigid body dynamics to shoot a projectile with the

already animated catapult from Chapter 8. Open the scene file

catapult_anim_v2.mb from the Catapult_Anim project downloaded from

the companion website.

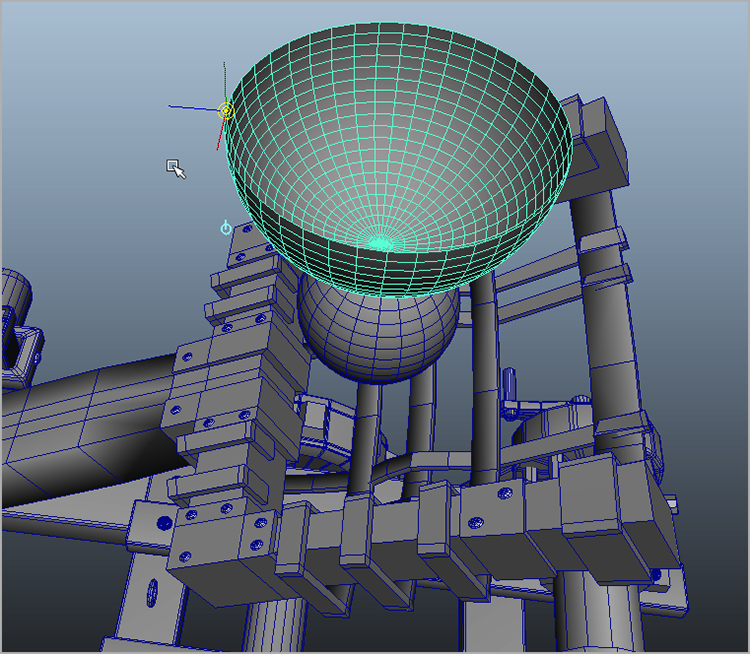

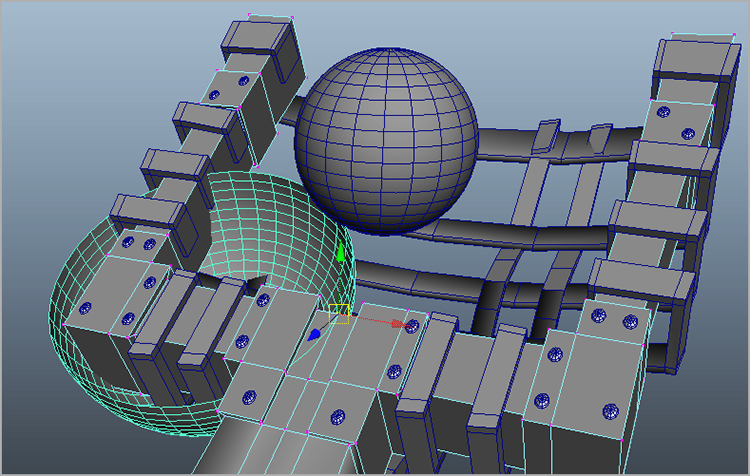

- For the projectile, create a polygon sphere and place it above the

basket, as shown in Figure 12-3.

Figure 12-3: Place a sphere over the basket.

Since dynamics takes a lot of calculations, to make things easier you will create an invisible object to be the passive rigid body collider instead of the existing geometry of the basket itself. This is a frequent workflow in dynamics, where proxy geometry (often hidden) is used to alleviate calculations and speed up the scene.

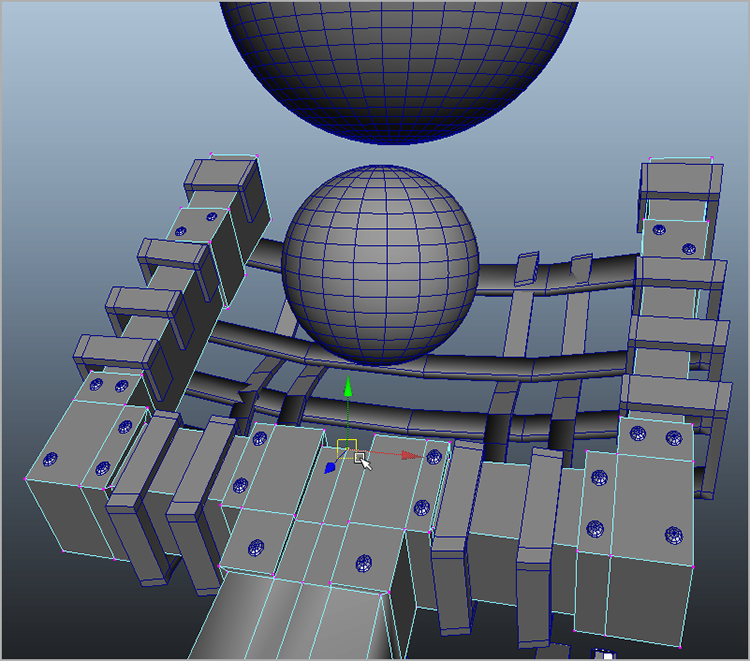

- Create another poly sphere with Axis Divisions and Height Divisions both set to 40.

- Select the top-half faces of the sphere and delete them to create a

bowl and place it over the catapult basket, as shown later in Figure 12-16. Use the D key

along with Point Snaps to place the bowl’s pivot point on the top rim of the

bowl, shown in Figure 12-4.

Figure 12-4: It puts the sphere in the basket, or else it gets the hose again.

The animation of the catapult arm is driven by a Bend deformer, so simply placing and grouping the bowl to the basket will not work. You will use a point on poly constraint to rivet the bowl to a vertex on the arm.

- Select the vertex shown in Figure 12-5; then Shift+select the bowl object. In the Animation menu

set, choose Constrain ⇒ Point On Poly.

The bowl will snap to the arm, as shown in Figure 12-6.

Figure 12-5: Select the vertex.

- Select the bowl and, in the Channel Box, click the pSphere2_pointOnPolyConstraint1 node. Set Offset Rotate Y to -90 and Offset Rotate X to 8 to place the bowl in the basket better (Figure 12-7).

- Go into the Dynamics menu set. Select the projectile sphere and at

frame 1 of the animation choose Fields ⇒ Gravity. The ball will instantly

become an active rigid body and will have a gravity attached. If you play back

your scene, the ball will simply fall through the bowl and catapult.

Figure 12-6: The bowl snaps to the arm at a weird angle.

Figure 12-7: Set offsets to place the bowl properly in the basket.

- Select the bowl object and choose Soft/Rigid Bodies ⇒ Create Passive Rigid Body to make the bowl a collision surface for the projectile ball. Play back your scene and bam! The projectile will bounce into the bowl as the catapult arm bends back, and the catapult will shoot the ball out.

- Select

the bowl object and press Ctrl+H to hide it. Now when you play back your scene,

the ball looks like it rests inside the catapult basket, as shown in Figure 12-8. The scene file

catapult_dynamics_v1.mbwill catch you up to this point.

Figure 12-8: The ball shoots!

If you play back the scene frame by frame, you’ll notice that the arm and basket will briefly pass through the projectile ball for a few frames as the arm shoots back up around frames 102–104. Increasing the subdivisions of the ball and the bowl before making them rigid bodies will help the collisions, but for a fun exercise, this works great. Play with the placement of the ball at the start of the scene, as well as the gravity and any other fields you care to experiment with, to try to land the projectile in different places in the scene.

Baking Out a Simulation

Frequently, you create a dynamic simulation to fit into another scene, perhaps to interact with other objects. In such cases, you want to exchange the dynamic properties of the dynamic body you have set up in a simulation for regular, old-fashioned animation curves that you can more easily edit. You can easily take a simulation that you’ve created and bake it out to curves. As much fun as it is to think of cupcakes, baking is a somewhat catchall term used to describe converting one type of action or procedure into another; in this case, you’re baking dynamics into keyframes.

You’ll take the simulation you set up earlier with the catapult and turn it into keyframes. Keep in mind that you can use this introduction as a foundation for your own explorations.

To bake out the rigid body simulation of the catapult projectile, follow these steps:

- Open the scene file

catapult_dynamics_v1.mbfrom the Catapult_Anim project on the web page, or if you prefer, open your own scene from the previous exercise. - Select the projectile ball (pSphere1) and choose Edit ⇒ Keys ⇒ Bake Simulation

. In the option

box, shown in Figure 12-9, set

Time Range to Time Slider (which should be set to 1 to 240). This, of course,

sets the range you would like to bake into curves.

. In the option

box, shown in Figure 12-9, set

Time Range to Time Slider (which should be set to 1 to 240). This, of course,

sets the range you would like to bake into curves. - Set Hierarchy to Selected and set Channels to From Channel Box. This

ensures you have control over which keys are created. Make sure Keep Unbaked

Keys and Disable Implicit Control are checked and that Sparse Curve Bake is

turned off. Before clicking the Bake or Apply button, select the Translate and

Rotate channels in the Channel Box. Click Bake.

Figure 12-9: The Bake Simulation Options window

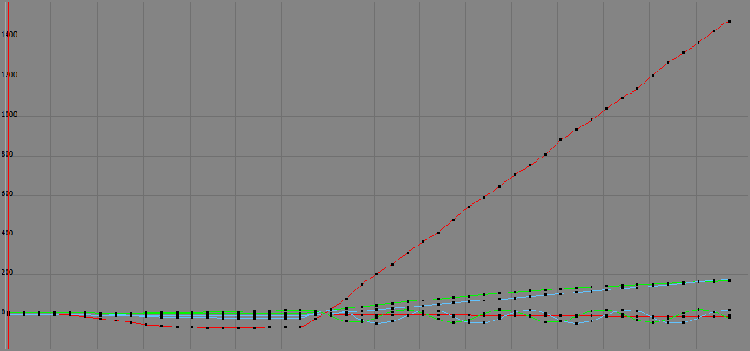

- Maya runs through the simulation. Scrub the timeline back and forth.

Notice how the projectile shoots as if the dynamic simulation were

running—except that you can scrub in the timeline, which you can’t do with a

dynamics simulation. With the projectile selected, open the Graph Editor; you’ll

see something similar to Figure

12-10.

Figure 12-10: The projectile has animation curves.

The curves are crowded; they have keyframes at every frame. A typical dynamics bake gives results like this. But you can set the Bake command to sparse the curves for you; that is, it can take out keyframes at frames that have values within a certain tolerance so that a minor change in the ball’s position or rotation need not have a keyframe on the curve.

- Let’s go

back in time and try this again. Press Z (Undo) until you back up to right

before you baked out the simulation to curves. You can also close this scene and

reopen it from the original project, if necessary. This time, select the

projectile sphere and choose Edit ⇒ Keys ⇒ Bake Simulation

. In the option

box, turn on the Sparse Curve Bake setting and set Sample By to 5. Select the Translate and Rotate channels in the

Channel Box and click Bake.

. In the option

box, turn on the Sparse Curve Bake setting and set Sample By to 5. Select the Translate and Rotate channels in the

Channel Box and click Bake. Maya runs through the simulation again and bakes everything out to curves. This time it makes a sparser animation curve for each channel because it’s setting keyframes only at five-frame intervals, as shown in Figure 12-11. If you open the Graph Editor, you’ll notice that the curves are much friendlier to look at and edit.

Figure 12-11: Sampling by fives makes a cleaner curve.

Sampling by fives may give you an easier curve to edit, but it may also oversimplify the animation of your objects; make sure you use the best Sampling setting for your simulation when you need to convert it to curves for editing.

Simplifying Animation Curves

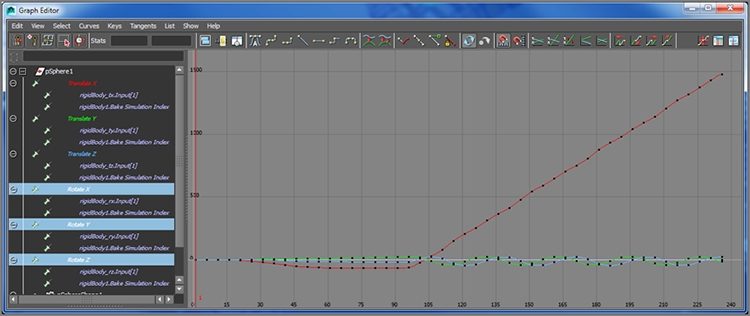

Despite a higher Sampling setting when you bake out the simulation, you can still be left with a lot of keyframes to deal with, especially if you have to modify the animation extensively from here. One last trick you can use is to simplify the curve further through the Graph Editor. You have to work with curves of the same relative size, so you’ll start with the rotation curves because they have larger values. To simplify the curve in the Graph Editor, follow these steps:

- Select the projectile and open the Graph Editor. In the left Outliner

side, select Rotate X, Rotate Y, and Rotate Z to display only these curves in

the graph view. Figure 12-12

shows the curves.

Figure 12-12: The Graph Editor displays the rotation curves of the projectile ball.

- In the left panel of the Graph Editor, select the

rigidBody_rx.Input[1] nodes displayed under the Rotate X, Y, and Z entries for

all three curves, as shown in Figure 12-13. In the Graph Editor menu, choose Curves ⇒ Simplify Curve

. In the option

box, set Time Range to All, set Simplify Method to Classic, set Time Tolerance

to 10, and set Value Tolerance to 1.0. These are fairly high values, but because

you’re dealing with rotation of the projectile, the degree values are high

enough. For more intricate values such as Translation, you would use much lower

tolerances when simplifying a curve.

. In the option

box, set Time Range to All, set Simplify Method to Classic, set Time Tolerance

to 10, and set Value Tolerance to 1.0. These are fairly high values, but because

you’re dealing with rotation of the projectile, the degree values are high

enough. For more intricate values such as Translation, you would use much lower

tolerances when simplifying a curve.

Figure 12-13: Select the curves to simplify them.

- Click Simplify, and you see that the curves retain their basic shapes but lose some of their keyframes. Figure 12-14 shows the simplified curves, which differ perhaps a little from the original curve that had keys at every five frames.

Simplifying curves is a handy way to convert a dynamic simulation to curves. Keep in mind that you may lose fidelity to the original animation after you simplify a curve, so use this technique with care. The curve simplification works with good old-fashioned keyframed curves as well; if you inherit a scene from another animator and need to simplify the curves, do it just as you did here.

Figure 12-14: A simplified curve for the rotations of the eight ball

nParticle Dynamics

Like rigid body objects, particles are moved dynamically using collisions and fields. In short, a particle is a point in space that is given renderable properties—that is, it can render out. When particles are used en masse, they can create effects such as smoke, a swarm of insects, fireworks, and so on. nParticles are an implementation of particles through the Maya Nucleus solver, which provides better and easier simulations than traditional Maya particles.

Although particles (and nParticles) can be an advanced and involved aspect of Maya, it’s important to have some exposure to them as you begin to learn Maya.

It’s important to think of particle animation as manipulating a larger system rather than as controlling every single particle. Particles are most often used together in large numbers so that the entirety is rendered out to create an effect. You control fields and dynamic attributes to govern the motion of the system as a whole.

Emitting nParticles

A typical workflow for creating an nParticle effect in Maya breaks out into two parts: motion and rendering. First, you create and define the behavior of particles through emission. An emitter is a Maya object that creates the particles. After you create fields and adjust particle behavior within a dynamic simulation, much as you would do with rigid body motion, you give the particles renderable qualities to define how they look. This second aspect of the workflow defines how the particles come together to create the desired effect, such as steam. You’ll make a locomotive pump emit steam later in this chapter.

To create an nParticle system, follow these steps:

- Make sure you’re in the nDynamics menu set, choose nParticles ⇒ Create nParticles, and select

Cloud. Choose nParticles ⇒ Create

nParticles ⇒ Create Emitter

. The option box

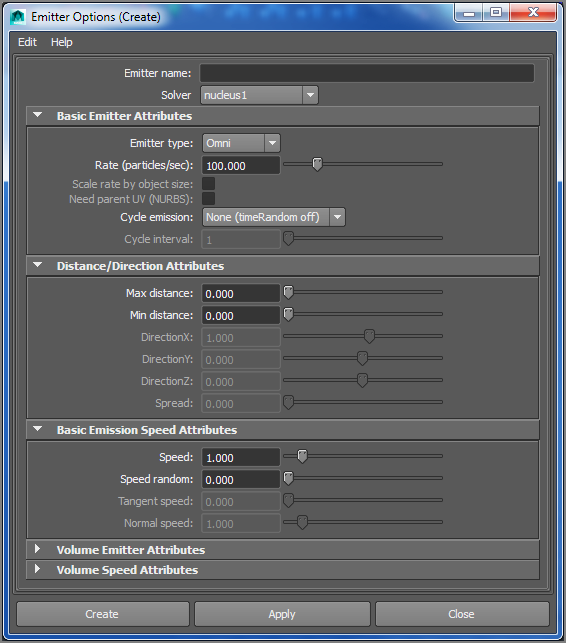

gives you various creation options for the nParticle emitter, as shown in Figure 12-15.

. The option box

gives you various creation options for the nParticle emitter, as shown in Figure 12-15.

Figure 12-15: Creation options for an nParticle emitter

The default settings create an Omni emitter with a rate of 100 particles per second and a speed of 1.0. Click Create. A small round object (the emitter) appears at the origin.

- Set your time range to 1–240 frames. Click the Play button to play the scene. As with rigid body dynamics, you must also play back the scene using the Play Every Frame option. You can’t scrub or reverse-play particles unless you create a cache file. You’ll learn how to create a particle disk cache later in this chapter.

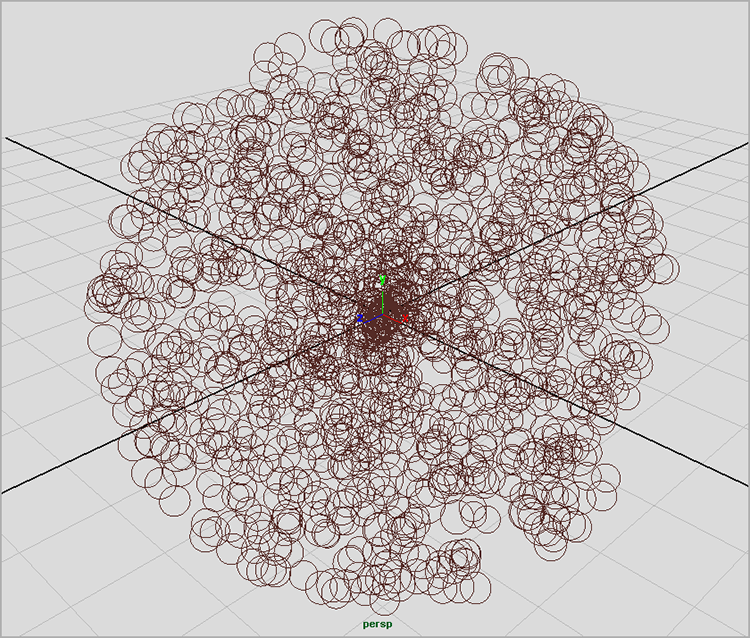

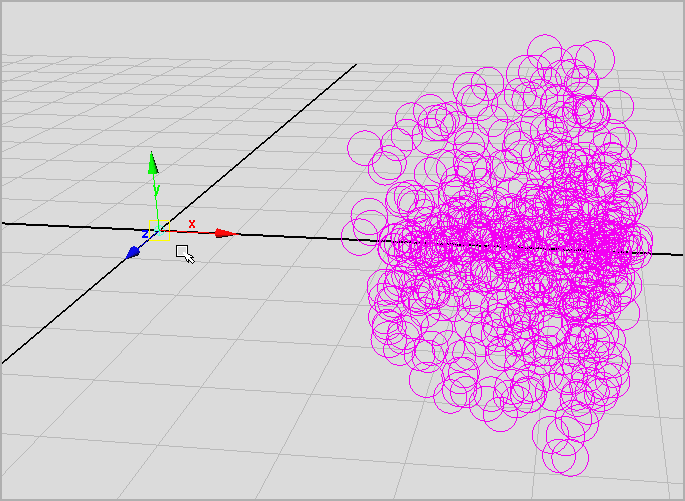

You’ll notice a mass of circles streaming out of the emitter in all directions (see Figure 12-16). These are the nParticles.

Figure 12-16: An Omni emitter emits a swarm of cloud particles in all directions.

Emitter Attributes

You can control how particles are created and behave by changing the type of emitter and adjusting its attributes. Here are the most often used emitters:

- Omni Emits particles in all directions.

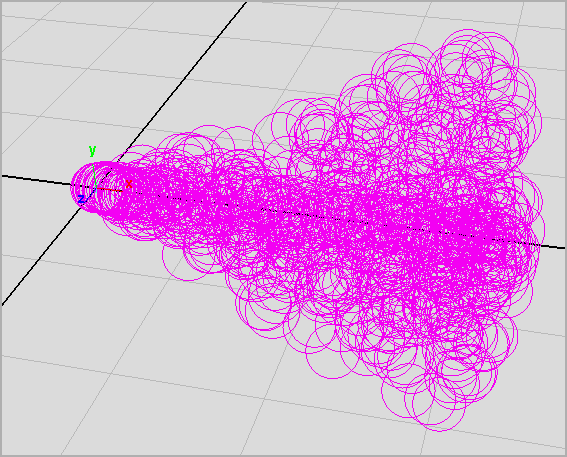

- Directional Emits a spray of particles in a specific direction, as shown

in Figure 12-17.

Figure 12-17: Cloud nParticles are sprayed in a specific direction.

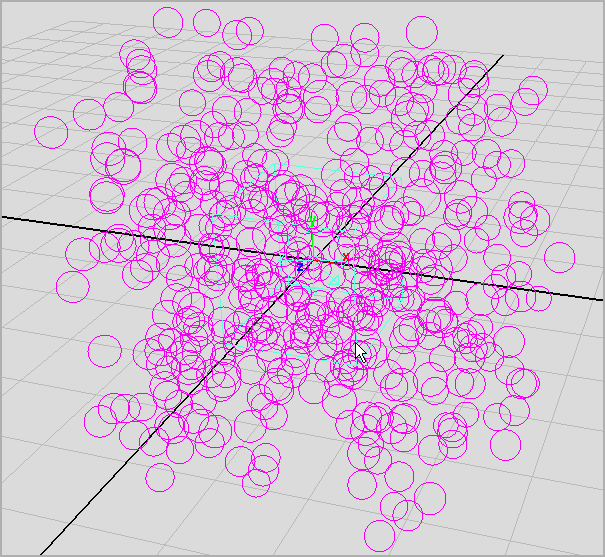

- Volume Emits particles from within a specified volume, as shown in Figure 12-18. The volume can

be a cube, a sphere, a cylinder, a cone, or a torus. By default, the particles

can leave the perimeter of the volume.

Figure 12-18: Cloud nParticles emit from anywhere inside the emitter’s volume.

After you create an emitter, its attributes govern how the particles are released into the scene. Every emitter has the following attributes to control the emission:

- Rate Governs how many particles are emitted per second.

- Speed Specifies how fast the particles move out from the emitter.

- Speed Random Randomizes the speed of the particles as they’re emitted, for a more natural look.

- Min and Max Distance Emits particles within an offset distance from the

emitter. You enter values for the Min and Max Distance settings. Figure 12-19 shows a

Directional emitter with Min and Max Distance settings of 3.

Figure 12-19: An emitter with Min and Max Distance settings of 3 emits cloud nParticles 3 units from itself

nParticle Attributes

After being created, or born, and set into motion by an emitter, nParticles rely on their own attributes and any fields or collisions in the scene to govern their motion, just like rigid body objects.

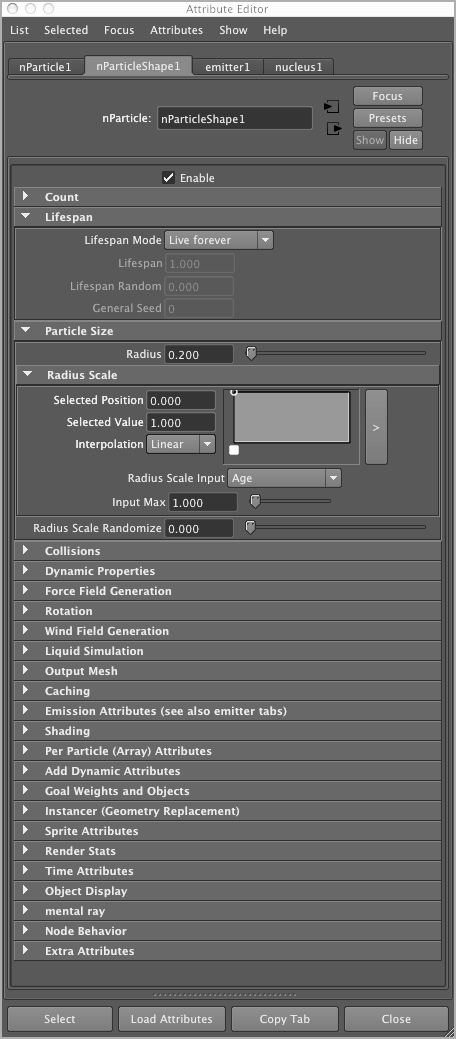

Figure 12-20: nParticle attributes

In Figure 12-20, the Attribute Editor shows a number of tabs for the selected particle object. nParticle1 is the particle object node. This has the familiar Translate, Rotate, and Scale attributes, like most other object nodes. But the shape node, nParticleShape1, is where all the important attributes are for a particle, and it’s displayed by default when you select a particle object. The third tab in the Attribute Editor is the emitter1 node that belongs to the particle’s emitter. This makes it easier to toggle back and forth to adjust emitter and particle settings.

The Lifespan Attributes

When any particle is born, you can give it a lifespan, which allows the particle to die when it reaches a certain point in time. As you’ll see with the steam locomotive later in the chapter, a particle that has a lifespan can change over that lifespan. For example, a particle may start out as white and fade away at the end of its life. A lifespan also helps keep the total number of particles in a scene to a minimum, which helps the scene run more efficiently.

You use the Lifespan mode to select the type of lifespan for the nParticle.

- Live Forever The particles in the scene can exist indefinitely.

- Constant All particles die when their Lifespan value is reached. Lifespan is measured in seconds, so upon emission, a particle with a Lifespan of 1.0 will exist for 30 frames (in a scene set up at 30fps) before it disappears.

- Random Range This type sets a lifespan in Constant mode but assigns a

range value via the Lifespan Random attribute to allow some particles to live

longer than others for a more natural effect.

Figure 12-21: The Particle Render Type drop-down menu

- LifespanPP Only This mode is used in conjunction with expressions that are programmed into the particle with Maya Embedded Language (MEL). Expressions are an advanced Maya concept and aren’t used in this book.

The Shading Attributes

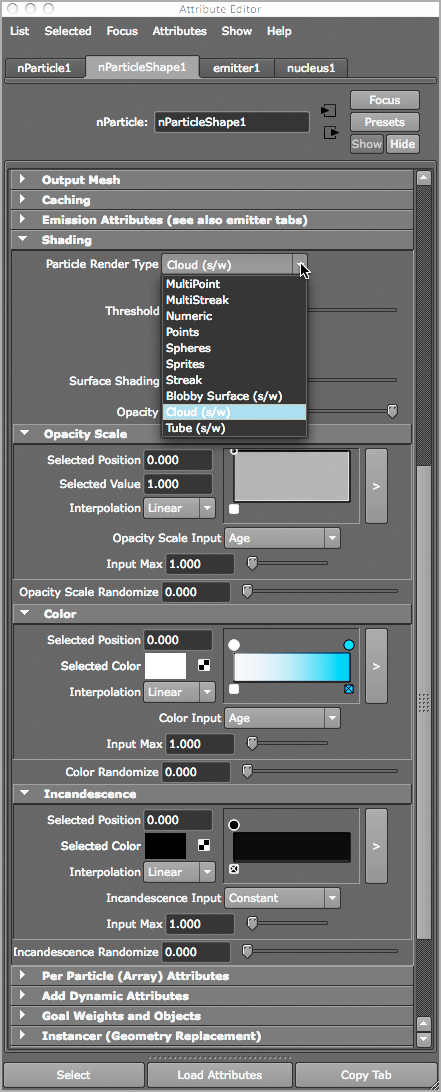

The Shading attributes determine how your particles look and how they will render. Two types of particle rendering are used in Maya: software and hardware. Hardware particles are typically rendered out separately from anything else in the scene and are then composited with the rest of the scene. Because of this compound workflow for hardware particles, this book will introduce you to a software particle type called Cloud. Cloud, like other software particles, can be rendered with the rest of a scene through the software renderer.

With your particles selected, open the Attribute Editor. In the Shading section, you’ll find the Particle Render Type drop-down menu (see Figure 12-21).

The three render types listed with the (s/w) suffix are software-rendered particles. All the other types can be rendered only through the Maya Hardware renderer. Select your render type, and Maya adds the proper attributes you’ll need for the render type you selected.

For example, if you select the Points render type from the menu, your particles change from circles on the screen to dots, as shown in Figure 12-22.

Figure 12-22: Dots on the screen represent point particles.

Several new attributes that control the look of the particles appear when you switch the Particle Render Type setting. Each Particle Render Type setting has its own set of render attributes. Set your nParticles back to the Cloud type. The Cloud particle type attributes are Threshold, Surface Shading, and Opacity. (See Figure 12-23.)

Figure 12-23: Each Particle Render Type setting displays its own set of attributes.

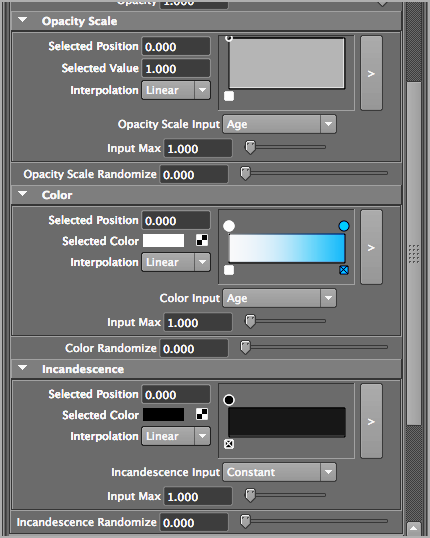

In the Shading heading, shown in Figure 12-24 for the cloud nParticles, are controls for the Opacity Scale, Color, and Incandescence attributes. They control how the particles look when simulated and rendered. Notice how each of these controls is based on ramps.

Figure 12-24: Controls for the Opacity Scale, Color, and Incandescence attributes

nParticles are already set up to allow you to control the color, opacity, and incandescence during the life of the particle. For example, by default, the Color attribute is set up with a white to cyan ramp. This means that each of the particles will begin life white in color and will gradually turn cyan toward the end of its lifespan, or Age setting.

Likewise, the Particle Size heading in the Attribute Editor contains a ramp for Radius Scale that works much the same way as the Color attribute just described. In this case, you use the Radius Scale ramp to increase or decrease the size of the particle along its Age setting.

nCaching Particles

It would be nice to turn particles into money cash, but I can only show you how to turn your particles into a disk cache. You can cache the motion of your particles to memory or to disk to make playback and editing of your particle animation easier. To cache particles to your system’s fast RAM memory, select the nParticle object you want to cache, and open the Attribute Editor. In the Caching section, under Memory Caching, select the Cache Data check box. Play back your scene, and the particles cache into your memory for faster playback. You can also scrub your timeline to see your particle animation. If you make changes to your animation, the scene won’t reflect the changes until you delete the cache from memory by selecting the particle object and unchecking the Memory Cache check box in the Attribute Editor. The amount of information the memory cache can hold depends on your machine’s RAM.

Although memory caching is generally faster than disk caching, creating a disk cache lets you cache all the particles as they exist throughout their duration in your scene and ensures that the particles are rendered correctly, especially if you’re rendering on multiple computers or across a network. You usually create a particle disk cache before rendering.

Creating an nCache on Disk

After you’ve created a particle scene and you want to be able to scrub the timeline back and forth to see your particle motion and how it acts in the scene, you can create a particle nCache to disk. This lets you play back the entire scene as you like, without running the simulation from the start and by every frame.

To create an nCache, make sure to be in the nDynamics menu set, select the nParticle object in your view panel or Outliner, and choose nCache ⇒ Create New Cache. Maya will run the simulation according to the timeline and save the position of all the particle systems in the scene to cache files in your current project’s Data/Cache folder. You can then play or even scrub your animation back and forth, and the particles will run properly.

If you make any dynamics changes to the particles, such as emission rate or speed, you’ll need to detach the cache file from the scene for the changes to take effect. Choose nCache ⇒ Delete Cache. You can open the option box to select whether you want to delete the cache files physically or merely detach them from the current nParticles.

Now that you understand the basics of particle dynamics, it’s time to see for yourself how they work.

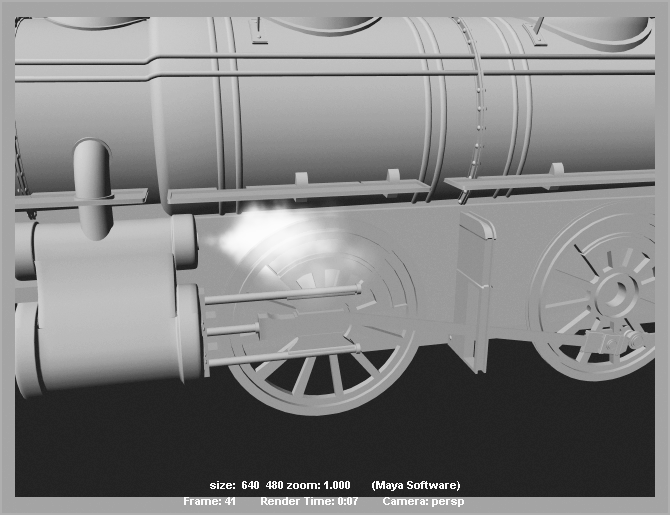

Animating a Particle Effect: Locomotive Steam

You’ll create a spray of steam puffing out of a pump on the side of a locomotive that

drives the wheels that you rigged previously. You’ll use the scene

fancy_locomotive_anim_v3.mb from Chapter 9, “More Animation!”

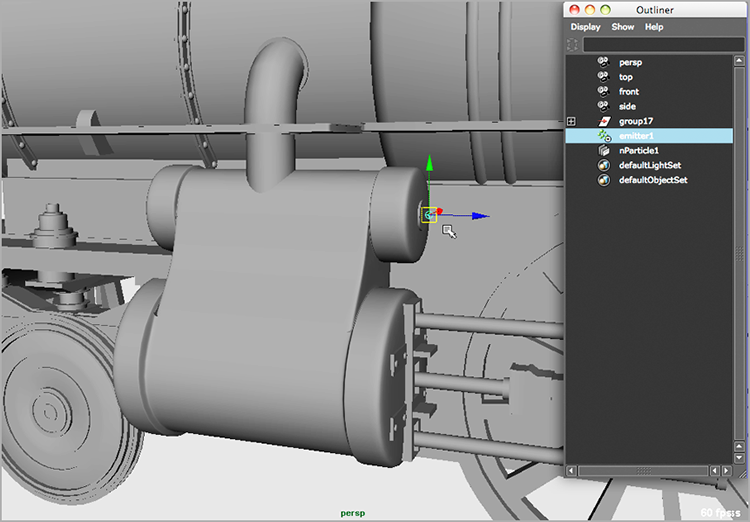

Emitting the nParticles

The first step is to create an emitter to spray from the steam pump and to set up the motion and behavior of the nParticles.

- In the nDynamics menu, choose nParticles ⇒ Create nParticles. Cloud should

still be checked in the Create nParticles menu. If it isn’t, select Cloud and

then choose nParticles ⇒ Create

nParticles ⇒ Create Emitter

. Set Emitter

Type to Directional and click Create. Place the emitter at the end of the pump,

as shown in Figure 12-25.

. Set Emitter

Type to Directional and click Create. Place the emitter at the end of the pump,

as shown in Figure 12-25. - To set up the emission in the proper direction, adjust the attributes of the emitter. In the Distance/Direction Attributes section, set Direction Y to 0, Direction X to 0, and Direction Z to 1. This emits the particles straight out of the pump over the first large wheel and toward the back of the engine.

- Play back your scene. The cloud nParticles emit in a straight line

from the engine, as shown in Figure 12-26.

You can load the file

Locomotive_Steam_v1.mafrom the Locomotive project on the web page to check your work.

Figure 12-25: Place the emitter at the end of the pump.

Figure 12-26: Cloud nParticles emit in a straight line from the pump.

- To change the particle emission to more of a spray, adjust the Spread

attribute for the emitter. Click the emitter1 tab in the particle’s Attribute

Editor (or select the emitter to focus the Attribute Editor on it instead) and

change Spread from 0 to 0.30. Figure 12-27 shows the new

cloud spray.

Figure 12-27: The emitter’s Spread attribute widens the spray of particles.

- The emission is rather slow for hot steam being pumped out as the locomotive drives the wheels, so change the Speed setting for the emitter from 1 to 2.0 and change Speed Random from 0 to 1. Doing so creates a random speed range between 1 and 3 for each particle. These two attributes are found in the emitter’s Attribute Editor in the Basic Emission Speed Attributes section.

- So that all the steam doesn’t emit from the same point, keep the

emitter’s Min Distance at 0, but set its Max Distance to 0.3. This creates a range of offset between 0 and 0.3 units for the

particles to emit from, as shown in Figure 12-28.

Figure 12-28: A range of offset between 0 and 0.3 units creates a more believable emission.

Setting nParticle Attributes

It’s always good to get the particles moving as closely to what you need as possible before you tend to their look. Now that you have the particles emitting properly from the steam pump, you’ll adjust the nParticle attributes. Start by setting a lifespan for them and then add rendering attributes.

Figure 12-29: The initial radius settings for the steam nParticles

- Select the nParticle object and open the Attribute Editor. In the Lifespan section, set Lifespan Mode to Random Range. Set Lifespan to 2 and Lifespan Random to 1. This creates a range of 1 to 3 for each particle’s lifespan. (This is based on a lifespan of 2, plus or minus a random value from 0 to 1.)

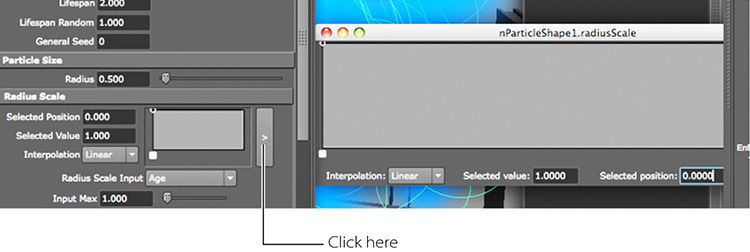

- You can control the radius of the particles as they’re emitted from the pump. Under the Particle Size heading in the Attribute Editor, set a Radius attribute of 0.50. Set the Radius Scale Randomize attribute to 0.25. This allows you to have particles that emit with a radius range between 0.25 and 0.75. Figure 12-29 shows the attributes.

- If you play back the simulation, you’ll see the particles are quite large initially. Because steam expands as it travels, you need to adjust the size (radius) of your nParticles to make them smaller at birth; they will grow larger over their lifespan and produce a good look for your steam.

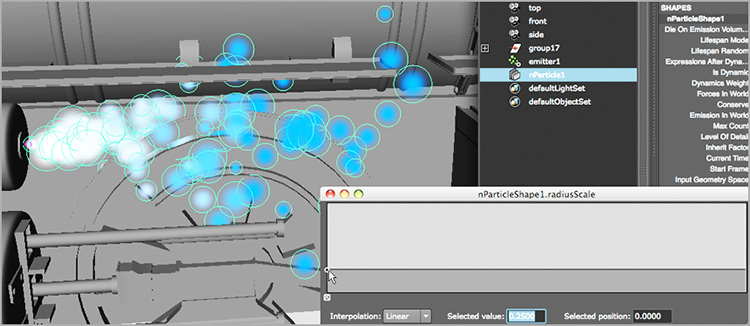

- In the Radius Scale heading in the Attribute Editor, click the arrow to the right of the ramp to open a larger view of the ramp, as shown in Figure 12-30.

- Click and drag the ramp’s first and only handle (an open circle at the

upper-left corner of the Ramp window) down to a value of about 0.25, as shown in

Figure 12-31. The

particles get smaller as you adjust the ramp value.

Figure 12-30: Open the Radius Scale ramp.

Figure 12-31: Decrease the radius of the nParticles using the Radius Scale ramp.

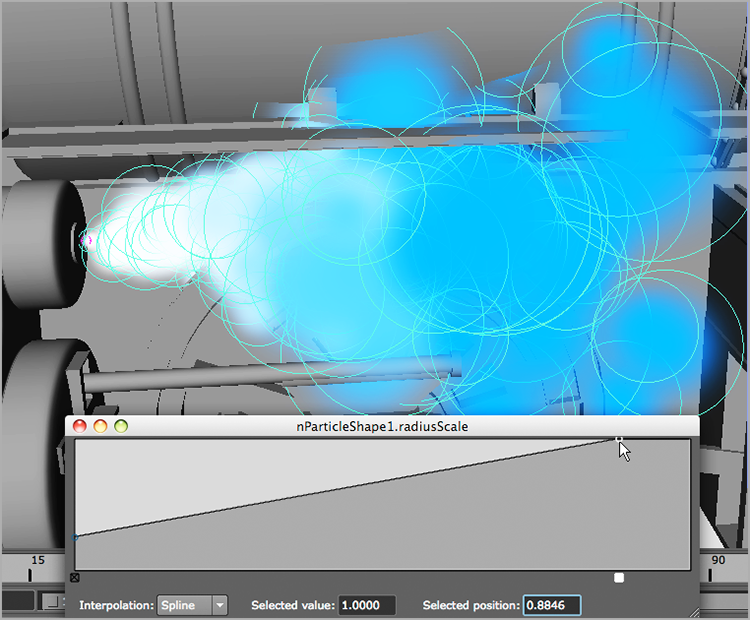

- To allow the particles to grow in size, add a second handle to the

scale curve by clicking anywhere on that line and drag to a value of 1.0 and the

position shown in Figure

12-32. The particles toward the end of the spray get larger.

Figure 12-32: Adjust the Radius Scale ramp to grow the particles.

- You can

set up collisions so the nParticle steam doesn’t travel right through the mesh

of the locomotive. Select the meshes shown in Figure 12-33 and choose nMesh ⇒ Create Passive Collider.

Figure 12-33: Select the meshes with which the nParticles will collide.

- In the Outliner, select the three nRigid nodes that were just created

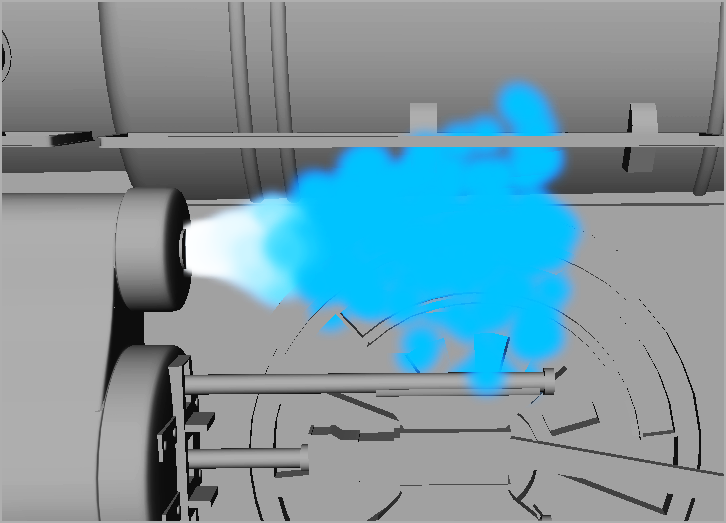

and set the Friction attribute in the Channel Box to 0.0 from the default of 0.10. Play back your scene, and your

particles now collide with the surface of the locomotive. (See Figure 12-34.)

Figure 12-34: The particles now react nicely against the side of the locomotive.

If you want to check your work, download the file locomotive_steam_v2.ma

from the Locomotive project on the web page.

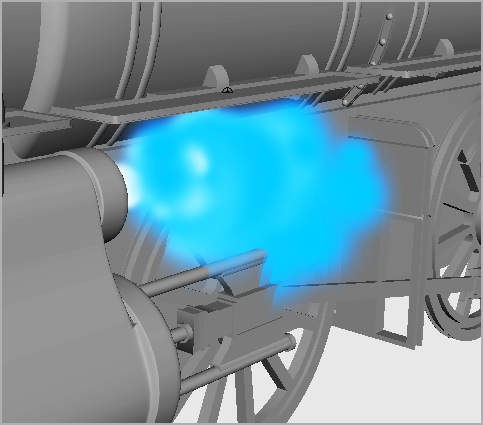

Setting Rendering Attributes

After you define the nParticle movement to your liking, you can create the proper look for the nParticles. This means setting and adjusting their rendering parameters.

- Select the nParticle object and open the Attribute Editor. Expand the Shading heading, and look at the Color ramp. By default, the particles go from white to light blue in color. Click the cyan color’s circle handle on top of the ramp. The Selected Color attribute next to the ramp shows the cyan color. Click in the swatch to open the Color Chooser and change the color to a very light gray.

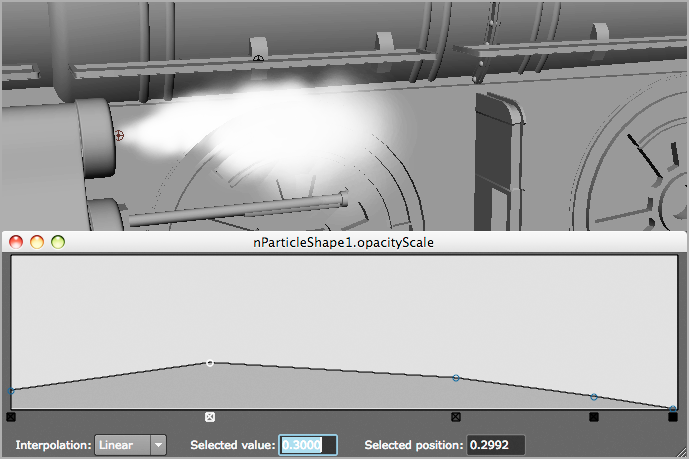

- Click the arrow bar to the right of the Opacity Scale ramp to open a larger ramp view. Grab the first handle in the upper-left corner and drag it down to a value of 0.12.

- The steam needs to be less opaque at its birth, grow more opaque

toward the middle of its life, and fade completely away at the end of the

particle’s life. Click to create new handles to create a curve for the ramp, as

shown in Figure 12-35. The

values for the five ramp handles shown from left to right are 0.12, 0.30, 0.20,

0.08, and 0.

Figure 12-35: Creating an Opacity ramp for the steam

- In the Render Settings window, set Image Size to

640×480. On the Maya Software

tab, set Quality to Intermediate Quality. Run the animation, and stop it when

some steam has been emitted. Render a frame. It should look like Figure 12-36. The steam

doesn’t travel far enough along the engine; it disappears too soon.

Figure 12-36: The steam seems too short and small.

With the steam nParticles selected, open the Attribute Editor; in the Radius Scale, under the Particle Size heading, change the first handle’s value from 0.25 to 0.35 to make the steam particles a bit larger. Below the Opacity Scale ramp is the Input Max slider; set that value to 1.6.

- Select the emitter1 tab, and change the Spread value for the emitter

to 0.2. Change Rate (Particles/Sec) to 200 and Speed to 3.0. Play back the simulation, and render a frame to compare to Figure 12-37.

Figure 12-37: A better emission, but a bit too solid

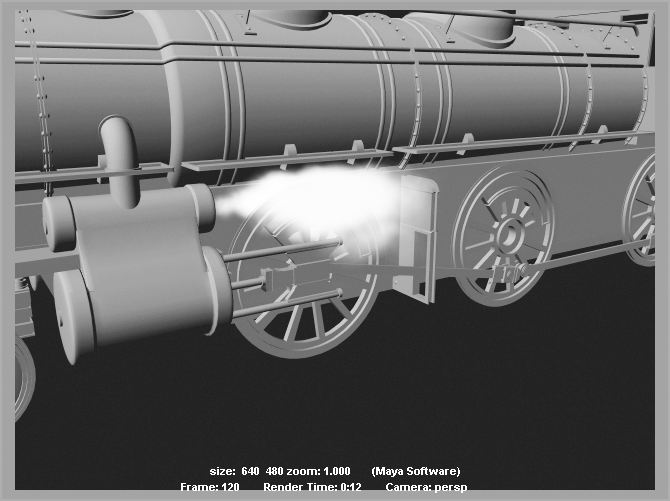

- The Color

ramp in the nParticle’s Attribute Editor controls the color of the steam, and a

shader is assigned to the particles. Select the steam nParticle object and open

the Hypershade window. In the Hypershade, click the Graph materials on the

selected object’s icon (

), as shown in Figure 12-38.

), as shown in Figure 12-38.

Figure 12-38: The shaders assigned to the cloud nParticle

- In the Hypershade, select the npCloudVolume shader and open the Attribute Editor. Notice that the attributes in the Common Material Attributes section all have connections. The ramp controls in the nParticle Attribute Editor are controlling the attributes in this Particle Cloud shader.

- Under the Transparency heading in the Attribute Editor for the shader,

set Density to 0.35. Try a render; the steam

should look better. (See Figure

12-39.)

Figure 12-39: The steam is less flat and solid.

Batch-render a 200-frame sequence of the scene at a lower resolution, such as 320×240, to see how the particles look as they animate. (Check the frames with FCheck. Refer to Chapter 11, “Autodesk® Maya® Rendering,” for more on FCheck.)

Open the file locomotive_steam_v3.ma from the Locomotive project on the

web page to check your work.

Experiment with the steam by animating the Rate attribute of the emitter to make the steam pump out in time with the wheel arm. Also, try animating the Speed values and playing with different values in the Radius and Opacity ramps. The steam you’ll get in this tutorial looks pretty good, but it isn’t as lifelike as it could be. Particle animators are always learning new tricks and expanding their skills, and that comes from always trying new things and retrying the same effects with different methods.

When you feel comfortable with the steam exercise, try using the cloud nParticle to create steam for a mug of coffee. That steam moves much more slowly and is less defined than the blowing steam of the locomotive, and it should pose a new challenge. Also try your hand at creating a smoke trail for a rocket ship, a wafting stream of cigarette smoke, or even the billowing smoke coming from the engine’s chimney.

Cloud nParticles are the perfect particle type with which to begin. As you feel more comfortable animating with clouds, experiment with the other render types. The more you experiment with all the types of nParticles, the easier they will be to harness.

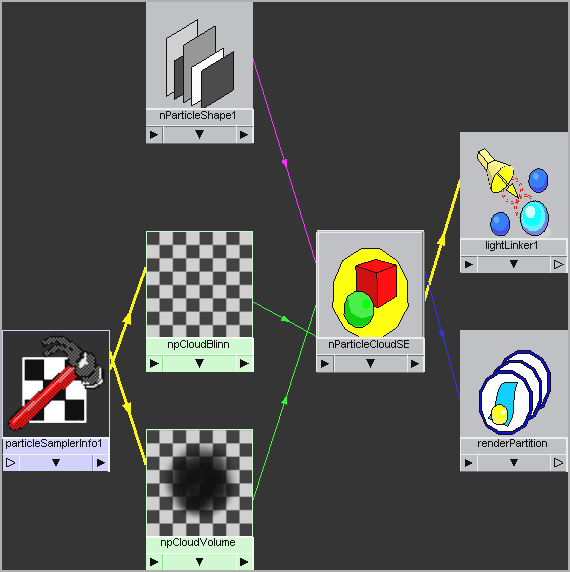

Introduction to Paint Effects

One of the tools in the effects arsenal of Maya is called Paint Effects. Using Paint Effects, you can create a field of grass rippling in the wind, a head of hair or feathers, or even a colorful aurora in the sky. Paint Effects is a rendering effect found in the Rendering menu. It has incredible dynamic properties that can make leaves rustle or trees sway in a storm. Paint Effects uses its own dynamics calculations to create natural motion. It’s one of the most powerful tools in Maya, with features that go far beyond the scope of this introductory book. Here you’ll learn how to create a Paint Effects scene and how to access all the preset brushes to create your own effects.

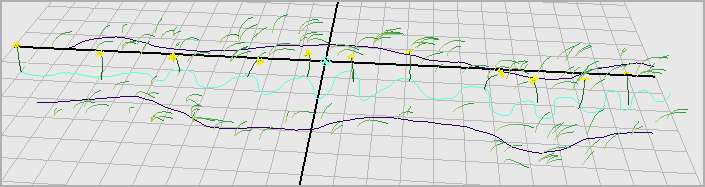

Paint Effects uses brushes to paint effects into your 3D scene. The brushes create strokes on a surface or in the Maya modeling views that produce tubes, which render out through the Maya Software renderer. These Paint Effects tubes have dynamic properties, which means they can move according to their own forces. Therefore, you can easily create a field of blowing grass.

- Try This Create a field of blowing grass and flowers; it will take you all of five minutes.

- Start with a new scene file. Maximize the perspective view. (Press the spacebar with the Perspective window active.)

- Switch to

the Rendering menu set (press F6). Choose Paint Effects ⇒ Get Brush to open the Visor

window. The Visor window displays all the preset Paint Effects brushes that

automatically create certain effects. Select the Grasses folder in the Visor’s

left panel to display the grass brushes available (see Figure 12-40). You can navigate the Visor window as

you would navigate any other Maya window, using the Alt key and the mouse

buttons.

Figure 12-40: The preset grass brushes in the Visor window

- Click the

grassWindWide.melbrush to activate the Paint Effects tool and set it to this grass brush. Your cursor changes to a Pencil icon. - In the Perspective window, click and drag two lines across the grid, as shown in Figure 12-41, to create two Paint Effects strokes of blowing grass. If you can’t see the grass in your view panel, increase Global Scale in the Paint Effects Brush Settings in either the Attribute Editor or the Channel Box to see the grass being drawn onto the screen.

- To change your brush so you can add some flowers between the grass,

choose Paint Effects ⇒ Get

Brush and select the Flowers folder. Select the

dandelion_Yellow.melbrush. Your Paint Effects tool is now set to paint yellow flowers.

Figure 12-41: Click and drag two lines across the grid.

- Click and drag a new stroke between the strokes of grass, as shown in

Figure 12-42.

Figure 12-42: Add new strokes to add flowers to the grass.

- Position your camera, and render a frame. Make sure you’re using Maya Software and not mental ray® to render through the Render Settings window and that you use a large enough resolution, such as 640×480, so that you can see the details. Render out a 120-frame sequence to see how the grass animates in the wind. Figure 12-43 shows a scene filled with grass strokes as well as a number of different flowers.

After you create a Paint Effects stroke, you can edit the look and movement of the effect through the Attribute Editor. You’ll notice, however, that there are a large number of attributes to edit with Paint Effects. The next section introduces the attributes that are most useful to the beginning Maya user.

Figure 12-43: Paint Effects can add flowers and grass to any scene.

Paint Effects Attributes

It’s best to create a single stroke of Paint Effects in a blank scene and experiment with adjusting the various attributes to see how they affect the strokes. Select the stroke and open the Attribute Editor. Switch to the stroke’s tab to access the attributes. For example, for an African Lily Paint Effects stroke, the Attribute Editor tab is called africanLily1.

Each Paint Effects stroke produces tubes that render to create the desired effect. Each tube (you can think of a tube as a stalk) can grow to have branches, twigs, leaves, flowers, and buds. Each section of a tube has its own controls to give you the greatest flexibility in creating your effect. As you experiment with Paint Effects, you’ll begin to understand how each attribute contributes to the final look of the effect.

Here is a summary of some Paint Effects attributes:

- Brush Profile Gives you control over how the tubes are generated from the stroke; this is done with the Brush Width attribute. This attribute makes tubes emit from a wider breadth from the stroke to cover more of an area.

- Shading and Tube Shading Gives you access to the color controls for the

tubes on a stroke.

- Color 1 and Color 2 From bottom to top, graduates from Color 1 to Color 2 along the stalk only. The leaves and branches have their own color attributes, which you can display by choosing Tubes ⇒ Growth.

- Incandescence 1 and 2 Adds a gradient self-illumination to the tubes.

- Transparency 1 and 2 Adds a gradient transparency to each tube.

- Hue/Sat/Value Rand Adds some randomness to the color of the tubes.

In the Tubes section, you’ll find all the attributes to control the growth of the Paint Effects effect. In the Creation subsection, you can access the following:

- Tubes Per Step Controls the number of tubes along the stroke. For example, this setting increases or decreases the number of flowers for the africanLily1 stroke.

- Length Min/Max Controls the height of the tubes to make taller flowers or grass (or other effects).

- Tube Width 1 and Width2 Controls the width of the tubes (the stalks of the flowers).

In the Growth subsection, you can access controls for branches, twigs, leaves, flowers, and buds for the Paint Effects strokes. Each attribute in these sections controls the number, size, and shape of those elements. Although not all strokes in Paint Effects create flowers, all strokes contain these headings.

The Behavior subsection contains the controls for the dynamic forces affecting the tubes in a Paint Effects stroke. Adjust these attributes if you want your flowers to blow more in the wind.

Paint Effects are rendered as a postprocess, which means they won’t render in reflections or refractions as is and they will not render in mental ray without conversion to polygons. They’re processed and rendered after every other object in the scene is rendered out in Maya Software rendering only.

To render Paint Effects in mental ray, you can convert Paint Effects to polygonal surfaces. They will then render in the scene along with any other objects so that they may take part in reflections and refractions. To convert a Paint Effects stroke to polygons, select the stroke and choose Modify ⇒ Convert ⇒ Paint Effects To Polygons. The polygon Paint Effects tubes can still be edited by most of the Paint Effects attributes mentioned so far; however, some, such as color, don’t affect the poly tubes. Instead, the color information is converted into a shader that is assigned to the polygons. It’s best to finalize your Paint Effects strokes before converting to polygons to avoid any confusion.

Paint Effects is a strong Maya tool, and you can use it to create complex effects such as a field of blowing flowers. A large number of controls to create a variety of effects come with that complexity. Fortunately, Maya comes with a generous sampling of preset brushes. Experiment with a few brushes and their attributes to see what kinds of effects and strange plants you can create.

Getting Started with nCloth

nCloth, part of the nucleus dynamics in Autodesk Maya, is a simple yet powerful way to create cloth simulations in your scene. From complex clothing on a moving character to a simple flag, nCloth dynamics can create stunning movement, albeit with some serious setup. I will very briefly touch on the nCloth workflow here to give you a taste for it and familiarize you with the basics of getting started.

Making a Tablecloth

Switch to the nDynamics menu set. The nMesh menu is where you need to start to drape a simple tablecloth on a round table in the following steps:

- Create a flat disc with a poly cylinder to make the basic table. Set the Y scale to .175 and the X and Z scales to 5.25. Set Subdivisions Axis to 36 for more segments to make the cylinder smoother.

- Create a poly plane with a scale of 20

to be larger than the cylinder. Set both the Subdivisions Width and Height to

40 for extra detail in the mesh. Place the

square a few units above the cylinder, as shown in Figure 12-44.

Figure 12-44: Place a square plane above a flat cylinder.

- Now you’ll set the plane to be a cloth object. Select the plane and choose nMesh ⇒ Create nCloth. The plane will turn purple, and a pair of new nodes is added to the scene: nucleus1 and nCloth1.

- Set your frame range to 1-240, and click Play. The plane falls down and through the cylinder object. The nucleus engine has already set up the nCloth plane to have gravity.

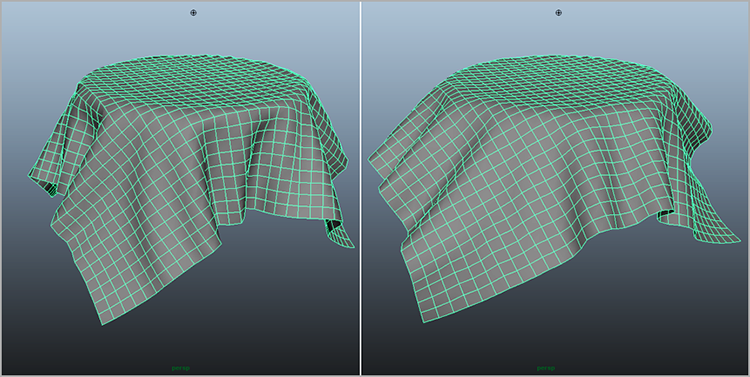

- Now let’s define the cylinder as a collision object to make it the tabletop for our tablecloth. Select the cylinder and choose nMesh ⇒ Create Passive Collider. That’s it! Click Play, and watch the cloth fall onto the table and take shape around it. Figure 12-45.

Well, as easy as that was, there’s a lot more to it to achieve the specific effect you may need. But you’re on the road already. The first thing to understand is that the higher the resolution of the poly mesh, the better the look and movement of the cloth, at the cost of speed. At 40 subdivisions on the plane, the simulation runs pretty well, but you can see jagged areas of the tablecloth, so you would need to start with a much higher mesh for a smoother result.

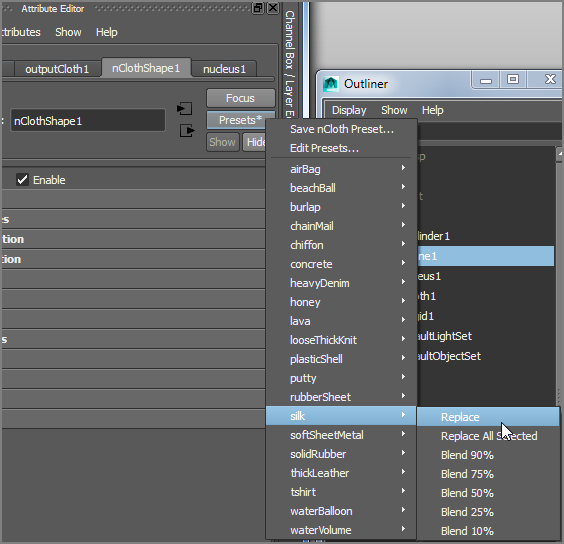

Select the tablecloth and open the Attribute Editor. A wide range of attributes can be adjusted for different cloth settings; however, you can choose from a number of built-in presets to make life easier. In the Attribute Editor, choose Presets*, as shown in Figure 12-46. Select Silk ⇒ Replace. As you can see, several Blend options appear in the submenu, allowing you to blend your current settings with the preset settings.

Figure 12-45: The cloth is working already!

Figure 12-46: The built-in nCloth presets

In this case, you’ve chosen Replace to set the tablecloth object to simulate silk. It will be lighter and airier than before. Figure 12-47 (left) shows the tablecloth at frame 200 with the silk preset. Now, in the Attribute Editor, choose Preset ⇒ thickLeather ⇒ Replace for a heavier cloth simulation (Figure 12-47, right). Notice the playback for the heavy leather was slower as well.

Figure 12-47: The silk cloth simulation is lighter (left); leather simulation is heavier and runs slower.

As a beginner to Maya, you may find it most helpful to go through the range of presets and see how the attributes for the nCloth change. Here is a preliminary rundown of some of the nCloth attributes found under the Dynamic Properties heading in the Attribute Editor. Try changing some of these values to see how your tablecloth reacts, and you’ll gain a finer appreciation for the mechanics of nCloth.

- Stretch Resistance Controls how easily the nCloth will stretch. The lower this value, the more rubbery and elastic the cloth will behave.

- Bend Resistance Controls how well the mesh will bend in reaction to external dynamic forces and collisions. The higher this value, the stiffer the cloth.

- Rigidity Sets the stiffness of the cloth object. Even a small value will have a stiffening impact on the simulation.

- Input Mesh Attract Compels the cloth mesh to reassume its original shape before the cloth simulation, which in our case is a flat square plane. At a value of 1, the cloth may not move at all. Using some Input Mesh Attract will also give the cloth object a stiffer and more resilient/rubbery appearance.

Making a Flag

Figure 12-48: Create the mesh for the flag.

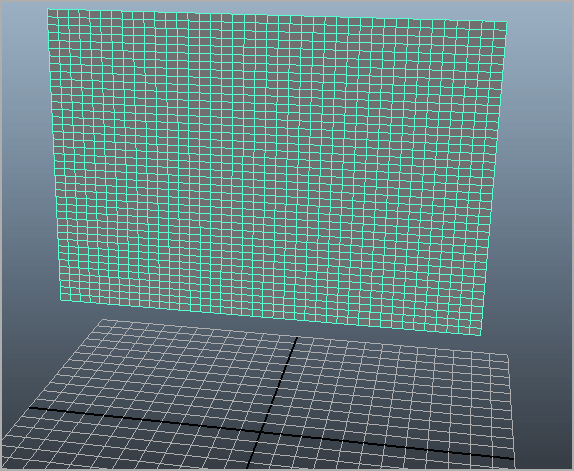

Now let’s make a quick flag simulation to get familiar with nConstraints.

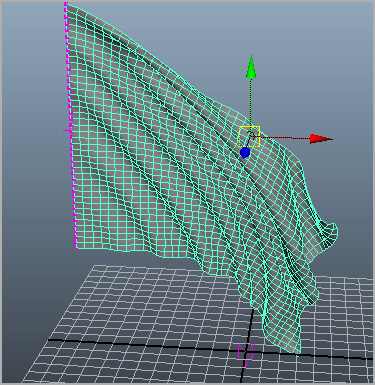

- Make a rectangular polygon plane that is scaled to (20, 14, 14) and with subdivisions of 40 in width and height. Orient and place it above the home grid, as shown in Figure 12-48.

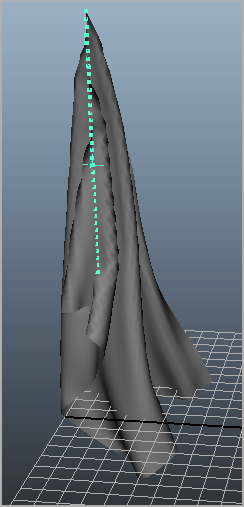

- With the flag selected, choose nMesh ⇒ Create nCloth. Set your frame range to 1-240, and click Play. The flag falls straight down. You need to keep one end from falling to simulate the flag being attached to a pole.

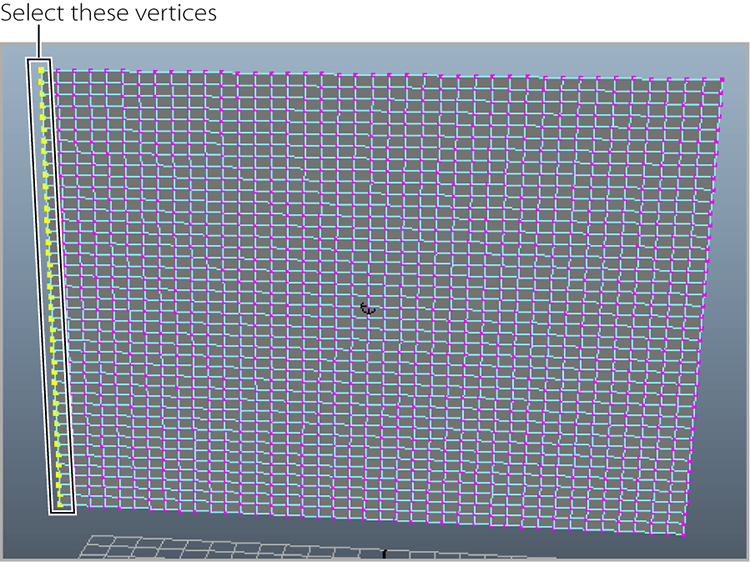

- Select the edge vertices on the left side of the flag, as shown in Figure 12-49, and choose

nConstraint ⇒ Transform. The vertices

you selected turn green. Now click Play, and the flag falls, while one end is

tethered as if on a pole (Figure

12-50).

Figure 12-49: Select the vertices for the nConstraint.

Figure 12-50: The flag is tethered to an imaginary pole now.

- Now

you’ll add wind to make the flag wave. Select the flag and open the Attribute

Editor. Click the nucleus1 tab, and under the Gravity and Wind heading, set the

Wind Speed attribute to 16. Figure 12-51 shows the flag flapping in the wind.

Figure 12-51: Wave the flag.

Adjust the Air Density, Wind Speed, Wind Direction, and Wind Noise attributes to adjust how the flag waves. You can use a similar workflow to create drapes blowing in an open window, for instance.

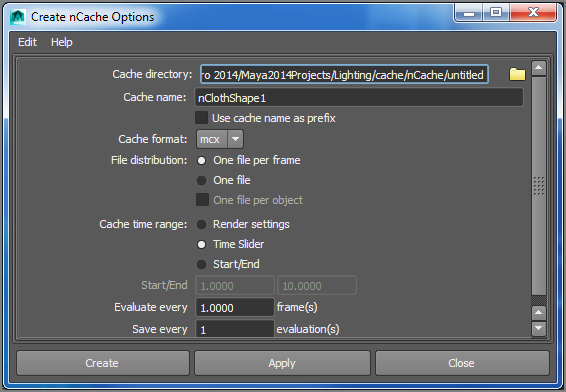

Caching an nCloth

Making a disk cache for a cloth simulation is important for better playback in your

scene. Also, if you are rendering, it’s always a good idea to cache your simulation

to avoid any issues. Caching an nCloth is very simple. Select the cloth object, such

as the flag from the previous example, and in the main menu bar, choose nCache ⇒ Create New Cache  . Figure 12-52 shows the options

for the nCache. Here you can specify where the cache files are saved as well as the

frame range for the cache. Once you create the cache, you will be able to scrub your

playback back and forth.

. Figure 12-52 shows the options

for the nCache. Here you can specify where the cache files are saved as well as the

frame range for the cache. Once you create the cache, you will be able to scrub your

playback back and forth.

Figure 12-52: Create nCache Options dialog box

If you need to change your simulation, you must first remove the cache before

changing nCloth or nucleus attributes. To do so, select the cloth object and choose

nCache ⇒ Delete Cache  . In the option box,

you can select whether you want to delete the cache files or just disconnect them

from the nCloth object.

. In the option box,

you can select whether you want to delete the cache files or just disconnect them

from the nCloth object.

You can reattach an existing cache file by selecting the nCloth object and choosing nCache ⇒ Attach Existing Cache File. The existing cache must be from that object or one with the same topology.

Customizing Maya

One of the most endearing features of Maya is its almost infinite customizability. Everyone has different tastes, and everyone works in their own way. Simply put, for everything you can do in Maya, you have several ways of doing it. There are always a couple ways to access the Maya tools, features, and functions as well.

This flexibility may be confusing at first, but you’ll discover that in the long run it’s very advantageous. The ability to customize enables the greatest flexibility in individual workflow.

It’s best to use Maya at its defaults as you first learn. However, when you feel comfortable enough with your progress, you can use this section to change some of the interface elements in Maya to better suit how you like to work.

User Preferences

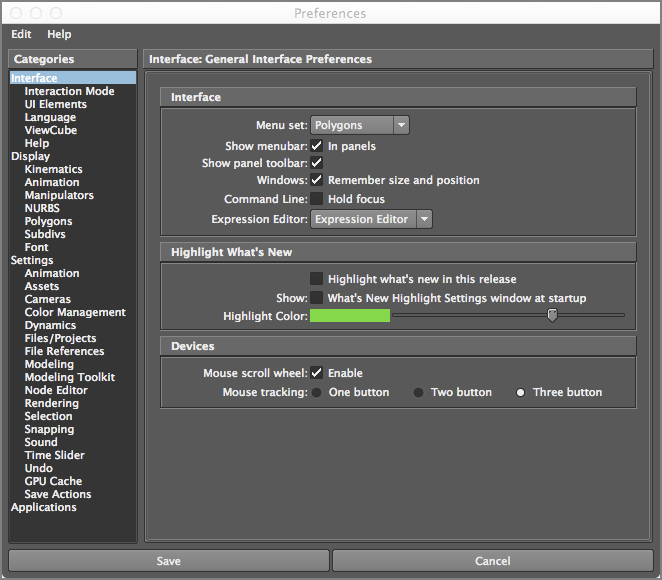

All the customization features are found under Window ⇒ Settings/Preferences, which displays the window shown in Figure 12-53.

Figure 12-53: The Settings/Preferences menu

The Preferences window (see Figure 12-54) lets you make changes to the look of the program as well as to toolset defaults by selecting from the categories listed in the left pane of the window.

Figure 12-54: The Preferences window

The Preferences window is separated into categories that define different aspects of the program. Interface and Display deal with options to change the look of the program. Interface affects the main user interface, whereas Display affects how objects are displayed in the workspace.

The Settings category lets you change the default values of several tools and their general operation. An essential aspect of this category is Working Units; these options set the working parameters of your scene (in particular, the Time setting).

By adjusting the Time setting, you tell Maya your frame rate of animation. If you’re working in film, you use a frame rate of 24 frames per second (fps). If you’re working in NTSC video (the standard video/television format in the Americas), you use the frame rate of 30fps.

The Applications category lets you specify which applications you want Maya to start automatically when a function is called. For example, while looking at the Attribute Editor for a texture image, you can click a single button to open that image in your favorite image editor, which you specify here.

Figure 12-55: The Shelf Editor

Shelves

Under the Shelf Editor command (Window ⇒ Settings/Preferences ⇒ Shelf Editor) lurks a window that manages your shelves (see Figure 12-55). You can create or delete shelves or manage the items on the Shelf with this function. This is handy when you create your own workflow for a project. Simply click the Shelves tab to display the icons on that Shelf in the Shelf Editor window. Click in the Shelf Contents section to edit the icons and where they reside on that selected Shelf. Clicking the Command tab gives you access to the MEL command for that icon when it is single-clicked in the Shelf. Click the Double Click Command tab for the MEL command for the icon when it is double-clicked in the Shelf.

You can also edit Shelf icons from within the UI without the Shelf Editor window. To add a menu command to the current Shelf, hold down Ctrl+Alt+Shift and click the function or command directly from its menu. Items from the Tool Box, pull-down menus, or the Script Editor can be added to any Shelf.

- To add an item from the Tool Box, MMB+drag its icon from the Tool Box into the appropriate Shelf.

- To add an item from a menu to the current Shelf, hold down the Ctrl+Alt+Shift keys while selecting the item from the menu.

- To add an item (a MEL command) from the Script Editor, highlight the text of the MEL command in the Script Editor and MMB+drag it onto the Shelf. A MEL icon will be created that will run the command when you click it.

- To remove an item from a Shelf, MMB+drag its icon to the Garbage Can icon at the end of the Shelf or use Window ⇒ Settings/Preferences ⇒ Shelf Editor.

Hotkeys

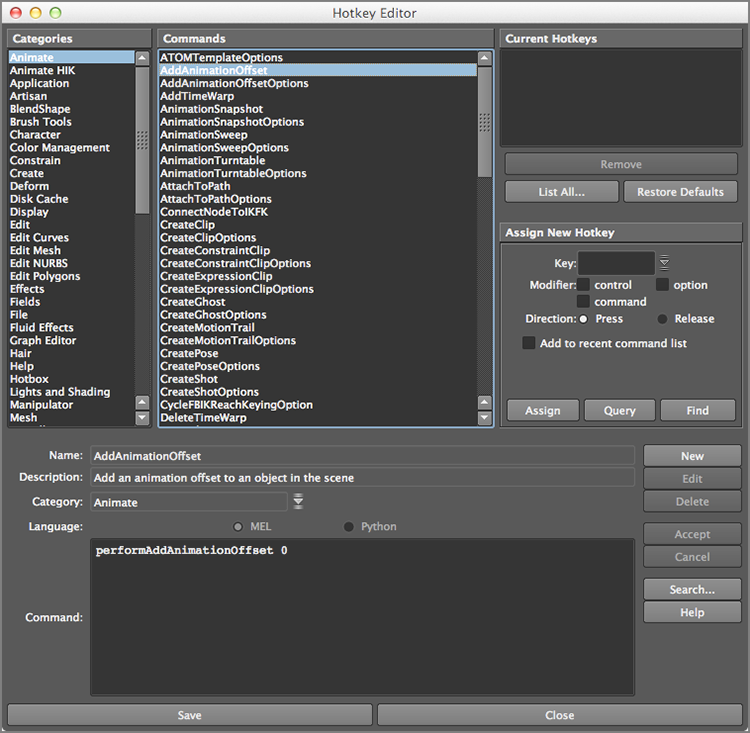

Hotkeys are keyboard shortcuts that can access almost any Maya tool or command. You’ve already encountered a few in your exploration of the interface and in the solar system exercise in Chapter 2, “Jumping into Basic Animation Headfirst.” What fun! You can create even more hotkeys, as well as reassign existing hotkeys, through the Hotkey Editor, shown in Figure 12-56 (Window ⇒ Settings/Preferences ⇒ Hotkey Editor).

Through this monolith of a window, you can set a key combination to be used as a shortcut to virtually any command in Maya. This is the last customization you want to touch. Because so many tools have hotkeys assigned by default, it’s important to get to know them first before you start changing things to suit how you work.

Every menu command is represented by menu categories on the left; the right side allows you to view the current hotkey or assign a new hotkey to the selected command. Ctrl and Alt key combinations may be used with any letter keys on the keyboard. Keep in mind that Maya is case sensitive, meaning that it differentiates between uppercase and lowercase letters. For example, one of my personal hotkeys is Ctrl+H to hide the selected object from view; Shift+Ctrl+H unhides it. (I’m sharing.)

The lower section of this window displays the MEL command that the menu command invokes. It also allows you to type in your own MEL commands, name them as new commands, categorize them with the other commands, and assign hotkeys to them.

Figure 12-56: The Hotkey Editor

Color Settings

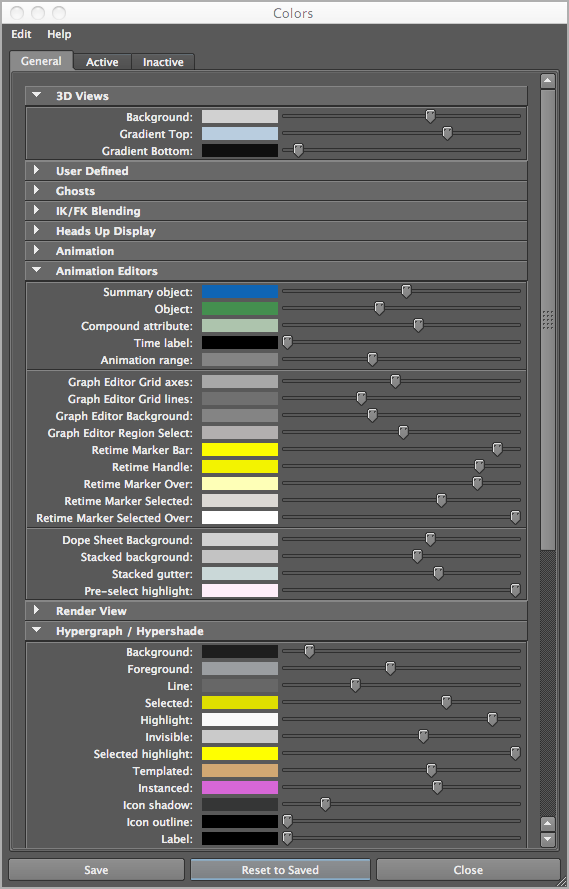

You can set the colors for almost any part of the interface to your liking through the Colors window shown in Figure 12-57 (Window ⇒ Settings/Preferences ⇒ Color Settings).

The window is separated into different aspects of the Maya interface by headings. The 3D Views heading lets you change the color of all the panels’ backgrounds. For example, color settings give you a chance to set the interface to complement your office’s decor as well as make certain items easier to read.

Figure 12-57: Changing the interface colors is simple.

Customizing Maya is important. However—and this can’t be stressed enough—it’s important to get your bearings with default Maya settings before you venture out and change hotkeys and such. When you’re ready, this section of this chapter will still be here for your reference.

Summary

In this chapter, you learned how to create dynamic objects and create simulations. Beginning with rigid body dynamics, you had a quick, fun exercise where you shot a projectile with the catapult, and then you learned how to bake that simulation into animation curves for fine-tuning. Next you learned about particle effects by creating a steam effect for a locomotive using nParticles. Next, you learned a little about the Maya Paint Effects tool and how you can easily use it to create various effects such as grass and flowers. Then you learned how to create cloth effects using nCloth to make a tablecloth and a flag, and finally, you learned how to customize Maya to suit your own preferences.

To further your learning, try creating a scene on a grassy hillside with train tracks running through. Animate the locomotive, steam and all, driving through the scene and blowing the grass as it passes. You can also create a train whistle and a steam effect when the whistle blows, and you can create various other trails of smoke and steam as the locomotive drives through.

The best way to be exposed to Maya dynamics is simply to experiment once you’re familiar with the general workflow in Maya. You’ll find that the workflow in dynamics is more iterative than other Maya workflows because you’re required to experiment frequently with different values to see how they affect the final simulation. With time, you’ll develop a strong intuition, and you’ll accomplish more complex simulations faster and with greater effect.

Where Do You Go from Here?

It’s so hard to say goodbye! But this is really a “hello” to learning more about animation and 3D!

Please explore other resources and tutorials to expand your working knowledge of Maya. Several websites contain numerous tips, tricks, and tutorials for all aspects of Maya; my own resources and instructional videos and links are online at http://koosh3d.com/ and on Facebook at facebook.com/IntroMaya, and you can contact or follow me through Twitter at @Koosh3d.

Of course, www.autodesk.com/maya has a wide range of learning tools. Now that you’ve gained your all-important first exposure, you’ll be better equipped to forge ahead confidently.

The most important thing you should have learned from this book is that proficiency and competence with Maya come with practice, but even more so from your own artistic exploration. Treat this text and your experience with its information as a formal introduction to a new language and way of working for yourself; doing so is imperative. The rest of it—the gorgeous still frames and eloquent animations—come with furthering your study of your own art, working diligently to achieve your vision, and having fun along the way. Enjoy, and good luck.