Chapter 2

Finding the Funding

IN THIS CHAPTER

Making a money plan

Making a money plan

Using your own money first

Using your own money first

Looking for an angel this side of heaven

Looking for an angel this side of heaven

Using venture capital

Using venture capital

Selling stock through an IPO and finding other sources of capital

Selling stock through an IPO and finding other sources of capital

Protecting your business plan

Protecting your business plan

Two common attitudes about start-up funds make the search for funds much more difficult. They are

- The more money I get, the better. I can use as much as I can get.

- My business plan numbers are just estimates — the investor will tell me what I need.

If you’re thinking like this, stop right now. First of all, why seek more investment money than you absolutely need? Every bit of capital invested in your business costs you some equity (ownership) in your company. Besides, having too much money may lead you to make poor decisions because you don’t think as carefully as you should about how you spend that money.

Secondly, although it’s true that your business plan financials are estimates, they had better be good estimates based on your research. Your investor may discount your estimate of rapid sales growth, but he or she wants to know that you’ve carefully considered all your numbers and that they make sense.

In this chapter, you see how to raise capital for your business the smart way — and you start with a plan.

Starting with a Plan

Before you talk to anyone — even your grandmother — about money, have a plan in place, a set of strategies for targeting the right amount of money from the right sources. Here are some guidelines for putting together a plan that works:

- Seek what you actually need, not what you think you can raise.

- Look at how your company grows and define the points when you’ll most likely need capital.

- Consider the sources of money available to you at each stage.

- Make sure that the activities of your business let you tap into the correct source of money at the right time. For example, if you know that you are planning an initial public offering (IPO) in three years, start putting in place the systems, controls, and professional management that you’ll need before the IPO takes place.

- Monitor your capital needs as you go so that you don’t have to return to the trough too many times. Every time you go back for another round of capital, you give up more stock in your company, and the percentage you own declines.

You can come out a winner if you prepare for your future capital needs. Just follow the lead of one technology company that produces custom productivity and e-commerce applications. This company keeps itself in a good position to raise capital by

- Creating value in the form of long-term customers and great products

- Running a profitable business

- Keeping cash flow positive

If you do these three things, you will probably not have difficulty raising growth capital whenever you need it. If you have a start-up venture, strive to achieve these goals from day one.

When you’re financing a traditional business

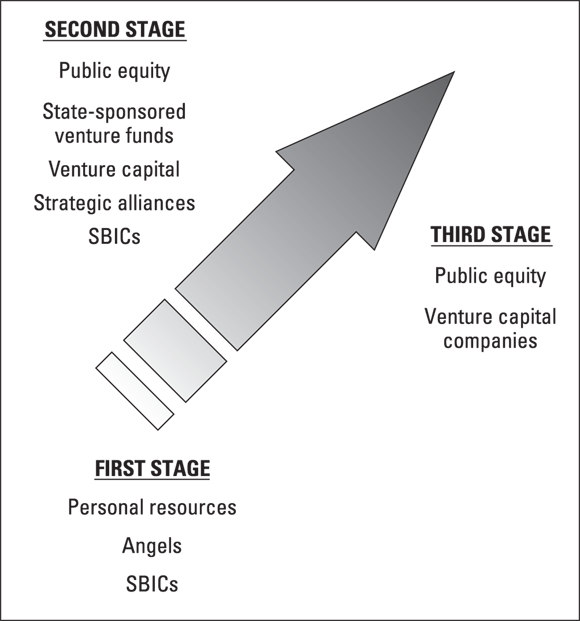

Traditional businesses (non-Internet businesses) typically follow fairly predictable financing cycles. Take a look at Figure 2-1 to see the stages of financing for a typical business.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 2-1: Three stages for financing the typical business.

First-stage funding is about getting seed capital to finish preparing the product and the business for launch. It’s also the stage where you seek funding to begin operations and reach a positive cash flow. In the second stage, you’re usually looking for growth capital. Your business has proven its concept and now you want to grow. Alternatively, your customers have demanded that your company grow to meet their needs (that’s a nice thing when it happens). To successfully use second-round financing, you need to be out looking for capital in advance of needing it.

Third-stage funding generally results in an acquisition or a buyout of the company. It’s the harvest stage for the entrepreneur who wants to take his or her wealth out of the business and possibly exit, or for investors who want to exit. In general, if you take on venture capital (a professionally managed pool of money), you are probably looking at a buyout or IPO within three to five years. That’s because a buyout or IPO provides the cash your investor needs to get out of the investment.

When you’re financing for e-commerce

It’s pretty easy to look at the funding stages of a traditional business, but the Internet has brought about some business models that don’t fit those stages well, if at all. Internet-based businesses (whose primary location is the Internet) require a strategy that is part formula and part artistic achievement. Such a strategy is ill defined at best. And sometimes it’s difficult to judge which concept is going to get funding before it launches, and which will have to bootstrap for a while to prove its concept.

- Don’t take the easy money. You want the smart money. It’s okay to fund a traditional business with money from friends, family, and lovers. Doing so isn’t a good idea, however, when you’re seeking early stage capital for an Internet concept. Who is funding your business is as important as how much they’re giving you. Be sure that you associate with people who attract the right kind of money to your venture.

- Get an introduction to the money source through one of your advisors. Be sure you exercise due diligence (fancy words for doing your homework — investigating the money source) on the investor to find one that has worked with your type of business before and has compatible firms in its portfolio that provide synergies with yours.

- Don’t get married on the first date. Large quantities of money are available for great Internet concepts. If you have such a concept, you may have more term sheets (agreements listing what an investor is willing to do) than you know what to do with. It’s tempting to grab the first term sheet under the assumption that the first is always the best. The agreement may be for the most money, maybe not, but the investor may not be the most compatible with your business. Compatibility is even more important than money, because the money source has a lot to say about what happens to your business. So, consider all your options before selecting one. Remember that the most important person to get to know in any potential investment firm is the partner you will be dealing with. If you don’t have a good feeling about that person, you may want to look elsewhere.

- Take the deal that moves you on to the next stage. The biggest deal doesn’t always win. What you’re looking for is enough money to get you comfortably to the next round of financing and an investment firm that adds value to what you’re doing in the form of introductions, contacts, advice, and so forth.

- Get your website up as quickly as possible. Don’t wait for the perfect site. Get up and running and start receiving feedback from potential customers. You need to keep the momentum going and collect data on the people who visit your site. This is important information to have when you talk to your investor.

- Buy the best management you can get with your capital. Investors are practically unanimous: The management team is more important than the business concept itself. When you obtain money, invest in the best management you can get. If you have to bootstrap with your own funds, seek a strategic alliance with a company whose great management you can leverage.

Tapping Friends and Family

The majority of entrepreneurs — well over 70 percent — start their businesses with personal savings, credit cards, and other personal assets like the proceeds from second mortgages and sale of stock portfolios. Why is that? With all the venture capital and private investor money out there for the taking, why do you have to use your own resources? The answer is simple: Your new company is just too big a risk — it’s unproven, and you don’t know for certain if the market will accept it. The only people who’ll invest in your business at this point are you and people who know and believe in you.

- Look for an office suite where you can share facilities and equipment with other tenants.

- Share office space with an established company that is compatible with yours. You may even be able to barter or trade services.

- To reduce cash needs, consider leasing rather than buying equipment.

- Barter with established companies for services.

- Get your customers to pay quickly. Sometimes a new company can get customers to pay a deposit upfront, providing capital for the raw materials you need to make the product.

- Ask your suppliers for favorable payment terms, and then pay on time. Those relationships become important to your business as it grows. You may find it necessary to request smaller amounts of credit from several suppliers until you establish your business.

Finding an Angel

The second most common source of capital for starting and growing a business is an angel, also known as a private investor. Angels are members of the informal risk capital market — the largest pool of capital in the United States. So, how do you find one of these gift-givers from heaven? Unfortunately, that’s the hard part because angels tend to keep a lower profile than any other type of investor. Entrepreneurs typically find angels through referrals from someone else. That’s why networking with people in your industry is so important when you begin thinking about starting a business. You need to build up a personal network to tap when it’s time to look for private investment capital.

How to spot an angel

There was a time when angels were into the investment for the long haul. Times have changed; angel investors have, too. Today, angel investors look a lot like professional venture capitalists. Angels typically ask you for the same credentials that a venture capitalist wants:

- A business plan

- Milestones

- A significant equity stake in the business

- A seat on the board of directors

The similarity between an angel and a venture capitalist came about because of the long bull market in the late 1990s when venture capital funding reached astronomical levels. Flush with cash, the venture capitalist stopped looking at deals that were less than $3 million to $5 million, leaving the playing field wide open for angels to step in, with the promise of a quicker turnaround.

Angels used to be characterized as middle-aged, former entrepreneurs who generally operated solo and invested near their homes. They usually funded deals for less than a million dollars and stayed in the investment for several years. Today, angels come in all ages, even turning up among the twenty-something Internet crowd who hit it big with their first ventures. Angels also band together to increase the size of their investment pools and take on larger deals. Networks like The Tech Coast Angels, based in California, consider themselves to be seed venture capitalists. They have become as sophisticated in their investment methods as any professional venture capitalist — exercising more due diligence and sometimes looking for a quicker return on their investment, often to the detriment of the business. In other words, they need to be cashed out of their investment before the growing business is in a position to do so. Entrepreneurs typically work with longer growth and performance horizons than venture capitalists and many of the new breed of angels. So their goals are often in conflict.

How to deal with angels

In many ways, you deal with angels the same as you deal with professional venture capitalists. You start with a good referral from someone who knows the angel well. Then:

- Make sure your goals and your angel’s goals are the same. Otherwise, you may risk the goals you’ve set for the business. Try to avoid an angel who wants to get in and out in three years or less. You can’t build an enduring business in that time frame. Besides, you need to find a way to buy out the investor at that point, and that may mean selling the business or offering an IPO, which may not have been your original plan.

- Exercise your own due diligence (investigation, background check) on the angel. Don’t be afraid to ask for references from other companies the angel has invested in. Talk to those entrepreneurs to find out what their experience was.

- Look for an angel who provides more than money. You want contacts in the industry, potential board members, and strategic assistance for your business. These things are as important as money.

- Get the angel’s commitment to help you meet certain business milestones that you both agree on.

Daring to Use Venture Capital

Venture capital is a professionally managed pool of funds that usually operates in the form of a limited partnership. The managing general partner pulls together a pool of investors — individual and institutional (pension funds and insurance companies, for example) — whose money he or she invests on behalf of the partnership. Typically, venture capitalists invest at the second round of funding and are looking for fast growth and a quick turnaround of their investment. Consequently, their goals often conflict with the entrepreneur’s goals for the company.

In the late 1990s, it appeared that all the rules about what a good investment is changed as venture capitalists began focusing on Internet companies and investing in ideas rather than intellectual property. They rushed to invest in companies like Amazon.com, Buy.com, and e-Toys, companies that weren’t projecting profits for several years. But as stock valuations of these companies plummeted to near zero levels in late 1999 and early 2000, venture capitalists began rethinking their strategies. They didn’t stop investing in Internet companies; they just started doing a better job of evaluating the opportunities.

What is still true about venture capital is that it funds less than 1 percent of all new ventures, mostly in technology areas — biotechnology, information systems, the Internet, and computer technology. To see how you may be able to use venture capital to your advantage, you first need to understand the cost of raising capital and the process by which it happens.

Calculating the real cost of money

Raising money for your business, whether private or venture capital, is a time-consuming and costly process. That’s why many entrepreneurs in more traditional businesses (non-high-tech or non-Internet) opt for slower growth, using internal cash flows as long as they can. But if you’ve decided to speed up your start-up or growth rate with outside capital, you need to have reasonable expectations about how that can happen. Here’s what you need to know:

- Raising money always takes longer than you planned, at least twice as long. Count on it.

- Plan to spend several months seeking funds, several more months for the potential investor to agree to fund your venture, and perhaps six more months before the money is actually in your hands.

- Use financial advisors experienced in raising money.

- Understand that raising money takes you away from your business a lot, probably when you most need to be there. So be sure to have a good management team in place.

After you find what you think is the ideal investor — you’re compatible, you have the same goals for the future of the company, and you genuinely like each other — the investor may back out of the deal. That’s right, after you’ve spent months trying to find this investor and even more time exercising due diligence (yours and the investor’s), the investor may change his or her mind. Perhaps the investor stumbled across something unfavorable; more likely, he or she couldn’t pull together the capital needed to fund your deal.

Investors often want to buy out your early investors, including your friends and family, typically out of the belief that first-round funders have nothing more to contribute to the venture. Investors also don’t want to deal with a bunch of small investors. A buyout like this can turn into an awkward situation if you haven’t explained to your early funders that it’s a possibility. And if you don’t agree to the buyout of the first round, understand that your investor may walk away from the deal.

After you receive the capital, the cost of maintaining it, ranging from paying interest on loans to keeping investors apprised of what’s going on with your business, can usually be paid out of the proceeds. You’ll also have back-end costs if you are raising capital by selling securities (shares of stock in your corporation). These costs include investment-banking fees, legal fees, marketing costs, brokerage fees, and any fees charged by state and federal authorities. The total cost of raising equity capital can reach 25 percent of the total amount of money you’re seeking. You see it definitely takes money to make money.

Tracking the venture capital process

The process that venture capitalists go through to analyze your deal, decide to make the deal, put together a term sheet, and exercise their due diligence can be quite complex and vary from firm to firm. In general, the process follows a predictable pattern, however. But first, consider what venture capitalists are looking for.

A venture capitalist invests in your company for a specified period of time (typically five years or less) with the expectation that at the end of that time, he or she gets the investment back plus a substantial return, in the neighborhood of 50 percent or more. The amount of return is a function of the risk associated with your venture. In the early stages, the risk is high, so the venture capitalist wants a higher return. Later, when your business has proven itself and you’re looking for second-round financing, the risk is less, so you have more clout in your negotiations.

The venture capitalist also probably wants a seat on your board of directors — a say in business strategy and policy.

Approving your plan

The first thing venture capitalists do is scrutinize your business plan, particularly to see whether you have a strong management team consisting of people experienced in your industry and committed to the launch of this venture. Then they look at your product and market to ensure the opportunity you’ve defined is substantial and worth their effort and the risk they’re taking. If you have a unique product that is protected through patents, you have an important barrier to competitors that is attractive to the venture capitalists, who also look at the market to ensure a significant potential for growth — that’s where they make their money, from the growth in value of your business.

If the venture capitalists like what they see, they’ll probably call for a meeting at which you may be asked to present your plan. They want to confirm that your team is everything you say it is. The venture capitalists may or may not discuss initial terms for an agreement at the meeting. It is likely they’ll wait until they’ve exercised due diligence.

Doing due diligence

If you’ve made it past the meeting stage, and the venture capitalists feel positive about your concept, it’s time for them to exercise due diligence, meaning they thoroughly check out your team and your business concept (or business, as the case may be). Once they’re satisfied that you check out, they’ll draw up legal documents detailing the terms of the investment. But don’t hold your breath waiting. Some venture capitalists wait until they know they have a good investment opportunity before putting together the partnership that actually funds your venture. Others just take a long time to release the money. In any case, you can certainly ask what the next steps are and how long they’ll take.

Crafting the deal

Always approach a venture capitalist from a position of strength. If you sound and look desperate for money, you won’t get a good deal. Venture capitalists see many business concepts, but most of them aren’t winners. Your power at the negotiating table comes from proving that your concept is one of the winners.

- The amount of capital to be invested

- The timing and use of the money

- The return on investment to the investors

- The level of risk

The amount of capital the venture capitalist provides reflects need. However, it also depends on the risks involved, how the money will be used, and how quickly the venture capitalist can earn a return on the investment (timing). The amount of equity in your company that the venture capitalist demands depends on the risk and the amount of the investment.

Selling Stock to the Public: An IPO

The aura and myths surrounding the IPO (selling stock in your company on a public stock exchange) have grown with the huge IPOs undertaken by up-start dot-com companies that don’t have an ounce of profit to their names. The glamor of watching your stock appear on the exchange you’ve chosen and the attention you get from the media make you forget for a moment all the hard work that led to this point and all the hard work that you can expect to follow as your company strives every quarter to satisfy stockholders and investment analysts that you’re doing the right things.

It’s no wonder so many naïve entrepreneurs announce their intention to go public within three years (if not sooner) of starting their businesses. If they knew more about what it’s really like to launch a public company, these starry-eyed adventurers would think twice. You need to be doing your homework — reading, talking to people who have done it — before making the decision to do an IPO. Once you decide to go ahead, you set in motion a series of events that have a life of their own. Yes, you can stop the IPO up to the night before your company is scheduled to be listed on the stock exchange, but doing so will cost you a lot of money and time, not to mention bad publicity.

An IPO is really just a more complex version of a private offering. You file your intent to sell a portion of your company to the public with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and list your stock on one of the exchanges. When you complete the IPO, the proceeds go to the company in what is termed a primary offering. If, later on, you sell your shares (after restrictions have ceased), those proceeds are termed a secondary distribution.

Considering the pros and cons of going public

The real reason that many entrepreneurs choose to take their companies public is that an IPO provides an enormous source of interest-free capital for growth and expansion. After you’ve done one offering, you can do additional offerings if you maintain a positive track record. Other general advantages that companies derive from becoming publicly held are

- More clout with industry types and the financial community

- Easier ways for you to form partnerships and negotiate favorable deals with suppliers, customers, and others

- The capability to offer stock to your employees

- Easier ways for you to harvest the wealth you have created by selling some of your shares or borrowing against them

- The cost exceeds $300,000, and that doesn’t include the commission to the underwriter (the investment bank that sells the securities).

- The process is extremely time-consuming, taking most of your week for more than six months.

- Everything you and your company do becomes public information.

- You are now responsible first and foremost to your shareholders, not to your customers or employees.

- You may no longer have the controlling share of stock in your company.

- Your stock may lose value because of factors in the economy even if you’re running the company well.

- You face intense pressure to perform in the short term so that revenues and earnings rise, driving up stock prices and dividends to stockholders.

- The SEC reporting requirements are a huge and time-consuming burden.

Deciding to go for it

If you’ve weighed all the advantages and disadvantages and still want to go forward with an IPO, you need to have a good understanding of what happens during the months that precede the offering. In general, the process unfolds in a fairly predictable fashion.

Choosing the underwriter

You need to choose an underwriter that serves as your guide on this journey and, you hope, sells your securities to enough institutional investors to make the IPO a success. Like meeting a venture capitalist, you need to secure an introduction to a good investment banker through a mutual acquaintance and investigate the reputation and track record of any investment banker you’re considering. Many disreputable firms out there are looking for a quick buck. You also want to find an investment banker who’ll stay with you after the IPO and look out for the long-term success of the stock.

Once chosen, the investment banker drafts a letter of intent stating the terms and conditions of the agreement. The letter includes a price range for the stock, although this is just an estimate because the going-out price won’t be decided until the night before the offering. At that point, if you’re unhappy with the price, you can cancel the offering. You will, however, be responsible for some costs incurred.

Satisfying the SEC

You file a registration statement with the SEC. Known as a red herring, this prospectus presents all the potential risks of investing in the IPO and is given to anyone interested in investing. Following the filing of the registration statement, you place an advertisement, known as a tombstone, in the financial press announcing the offering. Your prospectus is valid for nine months after the tombstone is published.

You need to decide on which stock exchange your company will be listed. Here are the two best known in the U.S.:

- National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation (Nasdaq)

- New York Stock Exchange (NYSE)

The NYSE is the most difficult to qualify for listing. The NYSE is an auction market where securities are traded on the floor of the exchange so that investors trade directly with one another. By contrast, the Nasdaq is a floorless exchange that trades on the National Market System through a system of broker-dealers from respected securities firms.

Taking your show on the road

Many consider the road show to be the high point of the entire IPO process. It is exactly what it sounds like, a whirlwind tour of all the major institutional investors over about two weeks. The entrepreneur and the IPO team present the business and the offering to these potential investors, whom they hope to sign on. The goal is to have the offering oversubscribed so that it can be sold in a day.

One of the more important skills you need to have or develop if you intend to go the IPO route (or seek money from any source) is how to talk to money people. These people have seen so many presentations from so many people begging for their resources that they are jaded. You have to work hard to capture their attention, and that’s not an easy thing to do.

- Tell a great story. Investors want to hear why this is the best investment opportunity they’ve ever seen. In short, they want to know what’s in it for them, their return on investment. Entrepreneurs, by contrast, are more focused on what’s in it for the customer.

- The entrepreneur must tell the story. Not only must the entrepreneur/CEO tell the story, but he or she needs to write it as well. No one has the passion for the business that the founder does, and that passion means a higher valuation for the business. So, tell your own story, and tell it with energy and passion.

- Don’t exaggerate your story. Keep in mind that investors have heard it all, so you need to tell them what makes your company stand out from the crowd. And don’t hide potential problems or negatives your business may have. Recognize them and then tell investors what you intend to do about them.

- Get their attention. You can grab attention in many ways, but one of the best is to show your audience that you have a solution to a problem they’re experiencing. For example, Scott Cook of Intuit (Quicken, QuickBooks) started his story with a question: “How many of you balance your own checkbooks?” Every investor raised his or her hand. “How many of you like doing it?” Not one hand was raised. He explained that millions of people around the world dislike that task, but he had a product that would solve the problem. That approach definitely caught the investors’ attention.

Dealing with failure

Once in a while, even when you’ve done all the right things, the IPO can fail, like the Texas company that developed a computer that would stand up to the toughest environments — places like machine shops and hot restaurant kitchens. When the founder decided to raise money through a first registered stock offering on the Internet, it was a long and costly undertaking (more than $65,000) to secure the necessary approvals from the SEC. But finally the company began selling shares through its website, its sights set on raising between $1.5 million and $9.9 million. The offering period was 90 days, and at the end of that time the company had raised only about $300,000. Attempts to do a traditional offering failed as well, and the company filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. The total bill for the IPO was about $250,000, for which the company received nothing.

Finding Other Ways to Finance Growth

Equity is not the only way to finance the growth of your business. Debt vehicles — IOUs with interest — are another way to acquire the capital you need to grow. When you choose this route, you typically hand over title to a business or personal asset as collateral for a loan bearing a market rate of interest. You normally pay principal and interest on the note until it’s paid off. Some arrangements, however, combine debt and equity. For example, a debenture is a debt vehicle that can be converted to common stock at some predetermined time in the future. In the meantime, the holder of the debenture receives interest on his or her loan to the company.

Here are some of the more common sources of debt financing for growth:

- Commercial banks: Banks are better sources for growth capital than for start-up capital, because by the time you come to them, your company has, in all likelihood, developed a good track record. Banks make loans based on the Five C’s: character of the entrepreneur, capacity to repay the loan, capital needed, collateral the entrepreneur can provide to secure the loan, and condition of the entrepreneur’s overall financial health and situation. For entrepreneurs with new ventures, character and capacity become the overriding factors.

- Commercial finance companies: Also known as asset-based lenders, these companies are typically more expensive to use than commercial banks by as much as 5 percent above the prime interest rate. But they are also more likely to lend to a start-up entrepreneur than a commercial bank is. And when you weigh the difference between starting the business and not starting because of money, a commercial lender may not be that expensive.

Small Business Administration: For more than 60 years the SBA (

www.sba.gov) has provided many forms of financial assistance to small businesses. This assistance includes grants, counseling, and loan guarantees. SBA loan programs are designed to help small businesses obtain funding when they can’t obtain suitable financing through traditional means. The SBA doesn’t directly make loans to small businesses. Instead, it provides a guarantee to banks and other authorized lenders for loans provided to qualifying businesses.This guarantee protects the lender by promising to repay a portion of the loan in the event the borrower defaults. Therefore, an SBA loan application is not submitted directly to the agency but rather through an authorized lender. Note that not all lenders offer SBA loans, and authorized lenders may not offer all the several types of SBA loans. Because the SBA is a government agency, its programs frequently change based upon current fiscal policy. The following are three of the more typical SBA loan programs currently being offered:

- SBA 7(a) loans: This is the SBA’s traditional loan program. Currently, 7(a) loans have a maximum of $5 million and no minimum. The SBA guarantees 75–85 percent of the loan, depending on the loan amount.

- SBA Express: SBA Express aims to reduce all the paperwork associated with a traditional SBA loan. If you qualify at a bank, you can borrow up to $350,000 without going through the standard SBA application process. In fact, this program promises to give you a decision within 36 hours. Because the SBA guarantees these loans only to 50 percent of their face value, not all the SBA-qualified lenders have signed on to the program.

- Microloan program: This program provides up to $50,000 to help small business with funding for various needs, such as working capital, inventory, and equipment acquisition. The SBA provides funds to specially designated intermediary lenders — nonprofit, community-based organizations with experience in lending and providing other technical and management assistance. These intermediaries administer the microloan program for eligible borrowers. Each intermediary lender establishes its own credit requirements. Often these lenders require some sort of collateral as well as the personal guarantee of the business owner.

Guarding Your Interests

Trade secrets generally include sensitive company information that can’t be covered by patents, trademarks, and copyrights. Business plans are often considered trade secrets. The only method of protecting trade secrets is through contracts and nondisclosure agreements (NDA) that specifically detail the trade secret to be protected. No other legal form of protection exists. If you have any concerns about sharing your business plan with anyone outside your circle of trust, including employees or investors, consider creating a contract or a NDA.

Contracts

A contract simply is an offer or a promise to do something or refrain from doing something in exchange for consideration, which is the promise to supply or give up something in return. So you are asking your employees to not reveal your company’s trade secrets in exchange for having a job there (and not getting sued if they do reveal them).

In addition to using contracts with employees and others who have access to your trade secrets, make sure that no one has all the components of your trade secret. For example, suppose you develop a new barbecue sauce that you intend to brand and market to specialty shops. If you’re producing in large volumes, you obviously can’t do all the work yourself, so you hire others to help. To avoid letting them know how to reproduce your unique barbecue sauce, you can do three things:

- Execute a contract with them binding them to not disclose what they know about your recipe.

- Provide them with premixed herbs and spices so they don’t know exactly what’s in the recipe.

- Give each person a different portion of the sauce to prepare.

Nondisclosure agreements

Many entrepreneurs and small business start-ups try protecting their ideas through a nondisclosure agreement (NDA). An NDA is a document that announces the confidentiality of the material being shared with someone and specifies that the person or persons cannot disclose anything identified by the NDA to other parties or personally use the information. Providing an NDA to anyone you are speaking to in confidence about your business plan, or any other trade secret, is a good idea. Without it, you have no evidence that you provided your proprietary information in confidence; therefore, it can be considered a public disclosure — that is, no longer confidential.

You definitely want to work with an attorney when you construct your NDA, because it must fit your situation. Generic NDAs do not exist. If you want an NDA to be valid for evidence purposes, it must include the following:

- Consideration, or what is being given in exchange for signing the document and refraining from revealing the confidentiality

- A description of what is being covered (be sure this is not too vague or broad)

- A procedure describing how the other party will use or not use the confidential information

Whom should you have sign an NDA? Anyone who will become privy to your trade secret:

- Immediate family: Spouses, children, and parents do not usually require NDAs, but it wouldn’t be a bad idea to have them sign one anyway.

- Extended family and friends who will not be doing business with you: To meet the consideration requirement for the NDA, you typically offer $1 in compensation.

- Business associates or companies with which you might do business: Consideration, in this case, is the opportunity to do business with you. For example, if you show your business plan to a potential investor or creditor, the consideration is the stake in the business or the return on investment.

- Buyers: Buyers typically don’t sign NDAs because doing so may preclude them from developing something similar, or they may already be working on a similar concept. For example, a toy manufacturer may not sign NDAs from inventors if it has a large R&D department that continually works on new ideas for toys. Chances are it’s working on something that will be similar enough to potentially infringe on an inventor’s product.

Grabbing early brand recognition from competitors online takes a lot of money, a professional management team, and the capability to grow in a hurry. If that’s your business, here are some suggestions for maneuvering through the capital maze:

Grabbing early brand recognition from competitors online takes a lot of money, a professional management team, and the capability to grow in a hurry. If that’s your business, here are some suggestions for maneuvering through the capital maze:  But what if you don’t have a network of friends and family willing to give you money, or from whom you prefer not to take money? What do you do then? One thing you do is bootstrap — beg, borrow, and barter for anything that you can from products to services to an office site. One way to bootstrap is to avoid hiring employees as long as possible (employees are typically the single biggest expense of any business). Here are some other tips:

But what if you don’t have a network of friends and family willing to give you money, or from whom you prefer not to take money? What do you do then? One thing you do is bootstrap — beg, borrow, and barter for anything that you can from products to services to an office site. One way to bootstrap is to avoid hiring employees as long as possible (employees are typically the single biggest expense of any business). Here are some other tips:  But becoming a public company also has several disadvantages that you should carefully consider. Some of them include

But becoming a public company also has several disadvantages that you should carefully consider. Some of them include