8.

Picking the Lock to Nirvana

If you’re afloat, peering up at a panorama of tangerine trees and marmalade skies, lower your gaze. Chances are your shipmate just might be a girl with kaleidoscope eyes.

John Lennon was one of the chief spokespeople of the counterculture of the 1960s. “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (1967), composed by Lennon and Paul McCartney, extolled the benefits of the synthetic psychedelic lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and the growing desire of young people to, in the words of Harvard psychiatrist, political activist, and eventual public enemy number one, Dr. Timothy Leary, “Turn on, tune in, and drop out.”

LSD was first manufactured in a Swiss lab by pharmaceutical chemist Albert Hofmann in 1938, but first ingested by Hofmann in 1943.1 Immediately, scientists and researchers saw its potential—it was used in attempts to cure autism and treat convicts, among others—and the first commercial preparation, Delysid, hit the European market in 1947. Many different mind-altering drugs entered our societal lexicon during this period. Mescaline, a phenylethylamine derivative used in traditional Native American worship rituals, was purified from the peyote cactus. Psilocin, the active form of the tryptamine precursor psilocybin, was purified from indigenous “magic mushrooms” found in Mexico. While new to the American mainstream, these plants had been used for hundreds, sometimes even thousands, of years by different indigenous groups and cultures. Rituals involving naturally occurring hallucinogens have played a central role in the religions, and sometimes even the language of various tribes—in quests to find spirit animals, communicate with the dead, and seek out the divine. When Hofmann created LSD, all of a sudden scientists wanted in.

Drinking the Electric Kool-Aid

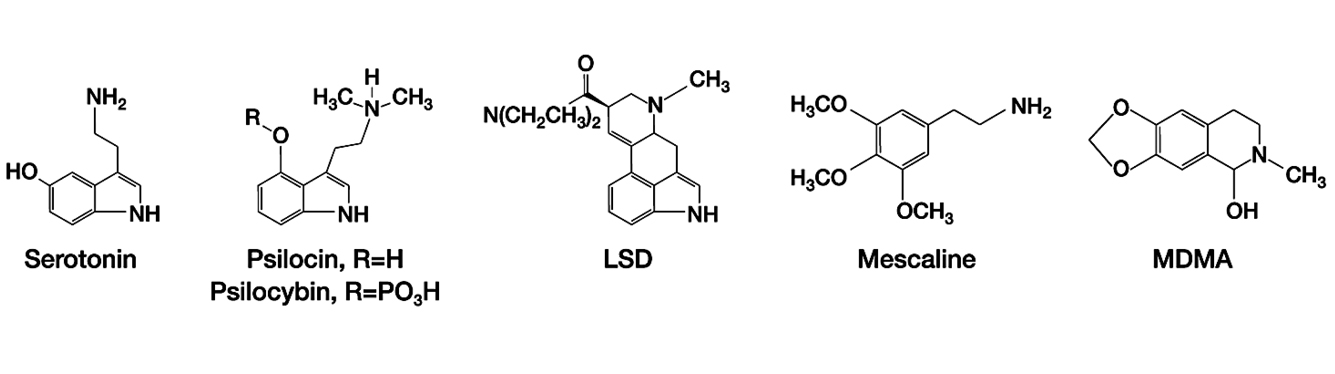

In 1953 the structure of serotonin and its presence in the brain was confirmed.2 Scientists soon thereafter discovered the incredible structural similarities between serotonin and some of these compounds—especially psilocybin and LSD (Fig. 8-1). Thus began a seventeen-year scientific and existential quest to unravel the hidden mysteries of the mind, and in particular, the quest for happiness—both natural and artificial. One set of scientists started altering the molecular structure of these compounds to increase their potency, while another set of scientists labeled them with radioactivity to look at their binding sites in the brain and their mechanisms of action. After years of trial and error, they discerned that these compounds acted as a serotonin agonist, meaning that they mimicked serotonin and would bind to specific serotonin receptors in the brain; namely, the -1a (see Chapter 7) and the -2a receptors.

Fig. 8-1: Serotonin receptor “skeleton keys.” Psychedelics are modifications of the structure of the parent compound serotonin. These changes allow different compounds to bind selectively to individual serotonin receptors instead of all sixteen. But some still cross-react. The tryptamine derivatives psilocybin and LSD can bind to both the serotonin-2a receptor (the mystical experience) and the serotonin-1a receptor (contentment). The phenylethylamine compound mescaline binds only to the serotonin-2a receptor. MDMA, or ecstasy (see Chapter 10), not only binds to the serotonin-2a receptor, it binds to the dopamine receptor as well.

The 1960s was the golden age of LSD research. The U.S. government subsidized at least 116 experiments (that we know of) over this interval to unlock its secrets. Dr. Stanislav Grof, one of the early experimenters, described LSD as a “non-specific amplifier of the unconscious,”3 for both good and bad. The suggestion was that LSD might be a primary modulator of the unconscious mind, and unlocking its mysteries would answer the questions of who we are, why we are here, and what’s to become of us. Big questions indeed. Maybe too big to be left to scientists?

As hard as you may try, you can’t keep something this big locked up in the lab. These molecules escaped from the ivory tower and started a (relatively) bloodless revolution within America, especially among young people, who were disillusioned with the U.S. government, and the handling of the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement. Psychedelics were all the rage in the late 1960s throughout the country. College campuses were the testing ground for this social experiment, and some still are.

Three observations about the use and users of psychedelics should be made at this point.

- Some users of psychedelics would experience “bad trips”; that is, they would experience unwanted fear and paranoia. Hallucinogenic experiences can’t be easily predicted. Maybe someone will have a good/mellow trip, feel at one with the universe, and talk to the deities—or maybe they will feel that their face is melting off and the world is contracting. It’s hard to predict what, who, and how these drugs cause a bad trip. In general, hallucinogens magnify the emotional and mental state of the user at the time. If someone is depressed or manic, a hallucinogen, taken on its own, would likely intensify the feeling in the same direction. Based on anecdotal data, the psychedelic experience is, in the words of Timothy Leary, responsive to both “set” (i.e., mind-set) and “setting” (i.e., place and people you are with). Perhaps this was best typified by the inconsistent and incoherent results of a clandestine CIA operation called the MK-ULTRA program (aka Operation Midnight Climax), which between 1953 and 1964 dosed unsuspecting military personnel and unwitting victims in New York and San Francisco with LSD in their alcoholic drinks.4 Ostensibly, the reason for this covert program was that the CIA was concerned that Russia, Communist China, and North Korea were using these drugs to brainwash American prisoners of war—think Laurence Harvey in The Manchurian Candidate (1962) (Queen of Diamonds, anyone?)—and they needed to fight back. The responses of these “volunteers” ranged from anxiety to sheer paranoia to apparent psychosis: their world did not make sense, because they were navigating blind. Thus, the need for informed consent and a tour guide for your metaphysical trip.

- Although some of these compounds demonstrated decreased efficacy (i.e., tolerance) with repeated use, few users of psychedelics demonstrated either dependence or withdrawal upon quitting.5 Most were able to walk away from their use without untoward personal or societal consequences. Virtually no emergency room visits, no spike in crime, and no users rushed into rehab, as is often the case when dopamine agonists (e.g., cocaine) or opiates (e.g., heroin) are withdrawn. It is estimated that as many as 30 million people worldwide have come into contact with a psychedelic drug at some point in time.6 For instance, a recent examination of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health demonstrated that of the respondents, 13.4 percent admitted to long-term psychedelic use. Yet, despite chronic use, these same people reported no drug addiction, and surprisingly little coincident mental illness; in fact, the prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses was lower in these users than in the general population,7 and few ended up in mental institutions (with the exception of some who have metaphorically fried their brains from too much acid). In other words, psychedelics are not classically addictive.

- A third and perhaps more important observation: recent research indicates that when LSD is ingested in a controlled setting, long-lasting effects are sometimes experienced, which can include improved social relationships with family, increased physical and psychological self-care, and increased sense of spirituality.8 Whether these feelings reflect a biochemical change in the brain, or are just an uplifting sequel to the mystical experience is unknown. But people report, for lack of a better term, mind-altering aftereffects.

The Feds Raid the Party

Proponents of psychedelic use such as Leary were gaining a foothold with America’s youth in the 1960s; it was a message that conflated with their anti-war sentiments. To quell the movement, California state senator Donald Grunsky introduced a law into the state legislature that banned possession, distribution, and importation of LSD and its cousin dimethyltryptamine (DMT), which was signed by Governor Ronald Reagan in 1966. The backlash culminated in the pinnacle of American counterculture: San Francisco’s 1967 Summer of Love, the vestiges of which are still apparent on Haight Street (come visit!—just ignore the hypodermic needles). Indeed, America’s youth, the first wave of the baby boomer generation, was dropping out in droves. “Think for yourself, and question authority” was Leary’s motto. Throughout adolescence and early adulthood, the cognitive connections between actions and consequences are muddled, as the maturation of the prefrontal cortex (the Jiminy Cricket) is not complete until approximately twenty-five years of age.9 (This is also why the actuaries jack up auto insurance rates until you reach your twenty-fifth birthday.) The baby boomers who attended Woodstock in 1969 struck fear in the heart of the U.S. government. After all, the Army needs young men to fight in wars. Generals and admirals in the armed forces, witnessing a clear change in young men’s taste for participating in armed conflict, advised the Nixon administration that these compounds were among the most dangerous and destructive drugs ever devised—even more destructive than opiates.

The counterculture movement abruptly went underground with Congress’s passage of the Controlled Substances Enforcement Act of 1970 and the establishment of the Drug Enforcement Administration in 1973, which was charged with regulating all dopamine, opioid, cannabinoid, and serotonin agonists. Heroin, marijuana, and all psychedelics were thereafter classified as Schedule I, meaning that they had no medicinal importance and no legal purpose; in other words, banned. With the stroke of a pen, Richard Nixon wiped out a fascinating and potentially promising line of medical and psychiatric research. Now relegated to the dustbin of scientific history, this work would languish for the next forty years. Deleted from our collective memory is the fact that some of the users of these compounds experienced what, for lack of a better phrase, was a “life transformation.” The anthem for this movement, Lennon’s Imagine, told young people to lay down their guns, part with their worldly possessions, and “learn to live as one.” Why did he believe this? Because he was singing Kumbaya with Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds? Can hallucinogens make you happy or, at a minimum, content? Not always: some have reported disembodiment and severe anxiety. And for how long? The length of the drug trip itself (which, for LSD, can be a very long twelve-plus hours)? Or are there lasting effects? Days? Months? Are humans happier in an altered state? The secrets of life, love, happiness, and contentment were buried in a tomb too dangerous to excavate.

Fast-forward to today. A courageous group of doctors and scientists are excavating that tomb right now. Some of these drugs are making a resurgence in science, albeit under extremely strict government oversight. Michael Pollan’s article “The Trip Treatment” in the New Yorker10 recounts the human interest story behind how these drugs have been rediscovered by some forward-thinking clinicians with the help of power brokers invested in unlocking their mysteries.

A New Death with Dignity?

Who on this earth is in greatest need of happiness, or at least the alleviation of the severest form of dysphoria or distress? Terminal cancer patients, that’s who. Standard hospice care provides such patients with opiates like hydromorphone (Dilaudid), which, while alleviating pain, dope them up to the point where they can’t and don’t care, and can’t even respond: they can’t tell their doctors that they are scared, or their loved ones that they love them. And of course these opiates are highly addictive. You could argue: Who cares about addiction if you’re already dying? Both of my parents died in hospice care, both doped up on opiates at the end. I couldn’t tell them I loved them, and they couldn’t communicate back. Prescribing opiates is more humane than letting patients suffer but nonetheless not an optimal way to depart this world. We all deserve a better exit than that, at peace with our own imminent mortality.

In a study that took a full decade to complete, and with the approval of the FDA, NIH, DEA, and a host of institutional review boards, Charles Grob at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center assessed the use of psilocybin (the compound in “magic mushrooms”) as a stand-alone treatment for the reactive anxiety and depression that attends death due to terminal cancer. In an initial study, twelve individuals with a life-threatening cancer diagnosis participated in a double-blind randomized crossover fashion (neither the subject nor the physician knew which treatment was being administered) with either psilocybin or niacin (Vitamin B3), which results in a tingling sensation, and acted as the placebo control.11 Furthermore, every subject was prepared by a licensed psychologist beforehand to minimize the possibility of any side effects or a bad trip. Each had their own personalized metaphysical tour guide, who remained with them through the session. They optimized the set and the setting by providing a pleasing and comfortable environment. These clinical research studies were carefully performed and documented, and above reproach. The results were quite remarkable. Feelings of “oceanic boundlessness” and “visionary restructuralization” were followed by positive mood and reduction in depressive scores, which persisted up to six months after the psilocybin treatment ended.

Several follow-up studies are now being conducted. Stephen Ross at NYU School of Medicine randomized twenty-nine participants with cancer in a double-blind fashion to receive either psilocybin or niacin. Again, reductions in long-term anxiety and depression were observed, and with long-lasting effects still measurable six months after hallucinogen exposure; and again the benefit correlated with the extent of the “mystical experience.”12 Using LSD as the hallucinogen, Peter Gasser in Switzerland13 showed that twelve cancer patients also showed short- and long-term benefit, and with no persistent side effects beyond the day of the study itself. Further studies have corroborated these beneficial effects up to fourteen months out.14

Due to the remarkable long-term nature of these clinical responses and the lack of long-term side effects, such studies are expanding. Currently, clinicians throughout the world are testing whether these compounds can treat addictions such as tobacco and alcohol.15 What? A psychedelic drug can confer contentment, even if artificial, or can reverse long-standing substance abuse? Not so fast. We’ll deal with this in Chapter 10.

Special on Receptors—Buy One, Get One Free!

Clearly, hallucinations and contentment are not the same thing. You don’t have to be in a mind-altered state to be happy. Second, most happy people have not lost touch with reality. Lastly and most importantly, not everyone who has experienced the effects of psychedelics has been moved to give up all their earthly possessions and live in a yurt. Nonetheless, there is clearly some form of overlap. What ties serotonin, hallucinations, and contentment together?

Although I can’t prove this, the key to this puzzle may very well lie in the nature of the compounds themselves, which serotonin receptors they activate, and where and how much it takes to activate them. Remember from Chapter 7, while originating in the DRN (one area of the midbrain), serotonin acts throughout the cerebral cortex, where it binds to as many as fourteen different receptors coded by eighteen different genes, likely mediating serotonin’s various cognitive, behavioral, and experiential effects. We also recall that the primary modulator of serotonin’s effects are the SSRIs, which improve mood and alleviate depression. As far as we can tell, the effects of SSRIs on anxiety and depression are on the serotonin transporter located at the serotonin-1a receptor.16, 17 How do we know? Because if you knock out that specific receptor in mice, they become incredibly anxious, and SSRIs can’t rescue them,18 yet knockout of other receptors doesn’t lead to depression. And because genetic polymorphisms in the seroronin-1a receptor predispose humans to major depressive disorder,19 the -1a receptor appears to be the seat of our contentment and well-being.

In contrast, through painstaking experiments on animals and humans, the mind-altering effects of all psychedelic compounds have been traced to their stimulatory effects on the serotonin-2a receptor. Not -1a but -2a. Punch your tickets to the Magical Mystery Tour—they are all chauffeured by the -2a receptor, whether it’s snorting Yopo, dropping acid, downing ayahuasca, or licking the Colorado River toad (yes, really—and do not try this at home).

Where are these serotonin-2a receptors that generate these vivid and otherworldly effects? Recently, Robin Carhart-Harris of Imperial College London delineated the two primary brain sites of hallucinogen action.20 First, the visual cortex. Injection of radio-labeled psilocybin lights up the visual cortex like a Christmas tree.21 Perhaps this is not all that surprising, given Lennon’s experiences of tangerine trees and marmalade skies. They are also in the prefrontal cortex (our Jiminy Cricket), which may explain why these compounds alter our inhibitions and increase sensations of reward.

But action on serotonin-2a receptors doesn’t explain the connection between some of the psychedelics and long-term contentment. You’d think that if all the hallucinogenic drugs bound to and activated the same serotonin-2a receptor, they would act in the same fashion and exert the same effects. But not all do. The phenylethylamine class of compounds, of which mescaline is the natural version (Fig. 8-1), isn’t associated with the post-administration experience of contentment.22 Rather, the afterglow appears to be restricted to the tryptamine class of compounds, of which psilocybin is the natural version.23 In fact, the drugs that provide contentment (-1a binding) on top of the mystical experiences (-2a binding) are all of the tryptamine class; and you have to reach a dose that achieves the mystical experience in order to experience the post-dosing contentment.24 Hey, two receptors for the price of one!25 In fact, virtually the entire tryptamine class of psychedelics (to which psilocybin and LSD belong) bind to both the -1a and -2a receptors.26 In contrast, mescaline binds just fine to the -2a receptor to provide the hallucinogenic experience, but it has little effect on the -1a receptor,27, 28 which likely accounts for the lack of the afterglow.

Could this added receptor bonus really explain the ability of psilocybin to remove angst and fear from terminal cancer patients? Can this extra effect really treat alcohol and tobacco addiction? Can this class of drugs really cause lions to lie down with lambs? Doubt it. I have met quite a few people who have dabbled in taking hallucinogens and none of them have become monks, although some did move to Marin County. Many addicts have at some time taken LSD and are still addicted to their drug of choice. Does the tour guide make a difference? Or the dosage? We don’t know yet . . . but can you see why the armed forces were so scared of the fallout?

The Psychedelic Hangover

More recent well-controlled studies of LSD administration in normal non-depressed volunteers suggest that the drug induces profound perceptual changes: the way these subjects see the world around them. Volunteers scored significantly higher on the Creative Imagination Scale,29 and exhibited more openness to new ideas and new experiences.30 Steve Jobs swore by LSD—until he started Apple. Then it became a distraction. What would it do to you? Chances are you won’t start a company, but you might end up down a rabbit hole that you can’t climb out of. You’re taking your brain in your hands. You ready for that?

Yet the implications of this research are nothing short of life- and world-altering. Fifty years ago it was a free-for-all. Then the pendulum swung in the opposite direction and the feds raided the party. Is there a happy medium? The pendulum is just now starting to swing back. What if tryptamine psychedelics (LSD and psilocybin) were reclassified to Schedule II, where doctors could prescribe them to selected patients in controlled settings? What if the taboo of hallucinogens was removed and we had “medical mushrooms”?

The big issue with all centrally acting drugs is the concern over tolerance and either withdrawal or dependence—in other words, their addictive potential (see Chapter 5). Despite demonstrating tolerance, these serotonin agonists have rarely been shown to lead to withdrawal or dependence; in other words, they do not appear to be classically addictive. In fact, they are now being evaluated to treat addictions to other drugs!31 Serotonin affects dopamine? We’re going there in Chapter 10.

Nonetheless, these serotonin agonists are not completely safe. High doses can on rare occasions cause constriction of the blood vessels and coronary artery spasms, so their recreational use without a doctor’s supervision is contraindicated. There is no doubt that repeated daily dosing of LSD leads to reduction of effect32 due to down-regulation of serotonin-2a receptors,33 which might have long-term sequelae that we just don’t know about. And the bad trips? This was ostensibly the reason Congress banned psychedelics back in 1970. In drug parlance, we’re talking about a very narrow therapeutic window, and if you’re not within the window, you might just jump out of it instead. Some of the newer designer hallucinogens can still elicit the occasional bout of agitation, rapid heartbeat, sweating, and combativeness that requires an ER visit and IV sedation until the drug wears off. Not ready for prime time, to say the least.

Better Living Through Biochemistry?

These studies provide yet another line of reasoning to support the assertion that I am trying to drive home—that our emotions are just the inward expression of biochemical processes in the brain. In the case of hallucinogens, signaling of the serotonin-1a receptor drives contentment, whereas signaling of the serotonin-2a receptor drives the mystical experience. In our modern society the role of mind-altering drugs to achieve heightened consciousness and/or contentment has yet to be determined, and will require careful scientific investigation in controlled settings along with philosophical and ethical debate before the public can be trusted with the key to nirvana.

We are our biochemistry, whether we like it or not. And our biochemistry can be manipulated. Sometimes naturally and sometimes artificially. Sometimes by ourselves but sometimes by others. Sometimes for good and sometimes for ill.