Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction

Abstract

The expectations for improved results in postmastectomy reconstruction for women have increased in the past decade. The modified radical mastectomy has given way to breast conservation techniques using principles of skin preservation. Skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomies have allowed plastic surgeons to perform breast reconstruction with the advantage of an intact skin envelope. Acellular dermal matrix is a biotechnological tissue prepared from either human or porcine skin. During processing, the cellular components that cause rejection and inflammation are removed, producing a structurally intact tissue matrix that serves as the biologic scaffold necessary for tissue ingrowth, angiogenesis, and tissue regeneration.

Keywords

• Breast • Implant • Surgery • Reconstruction • Acellular dermal matrix

Overview

The expectations for improved results in postmastectomy reconstruction for women in 2011 have increased in the past decade. The surgical treatment of breast cancer has evolved since the era of Halstead’s radical mastectomy. The modified radical mastectomy has given way to breast conservation techniques using principles of skin preservation. The ultimate manifestation of this advancement can be seen in skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomies. These innovations have provided plastic surgeons with the opportunity to perform breast reconstruction with the advantage of an intact skin envelope.

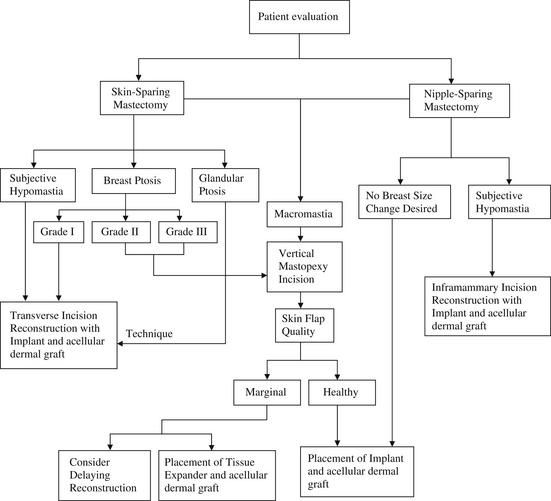

ADM is a biotechnological tissue prepared from either human or porcine skin. During processing, the cellular components that cause rejection and inflammation are removed, producing a structurally intact tissue matrix that serves as the biologic scaffold necessary for tissue ingrowth, angiogenesis, and, ultimately, tissue regeneration. ADM has been used extensively for soft tissue augmentation, including lip augmentation, depressed scar tissue repair, malar and submalar augmentation, rhinoplasty, and more recently for breast reconstruction. In all these settings, the ADM has shown good incorporation, with excellent postoperative healing, no resorption, and minimal risk for infection, extrusion, hematoma, or seroma. In addition, because this tissue is acellular, it may have greater tolerance for ischemia because it has the capability to remain in place without breakdown until vascular ingrowth and cellular integration develops. This process can be shown by a biopsy of the ADM at 6 weeks after surgery (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Histology specimens of biopsied AlloDerm®. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain; (B) Verhoeff stain. These samples show replacement of the acellular tissue matrix with cellular ingrowth, revascularization, and capsular architecture.

The Author’s Use of ADMS

In 2001, I began to make use of the unique properties of ADMs to provide coverage for either an implant or a tissue expander in breast reconstruction, and I have relied on 2 important conditions as selection criteria when deciding which type of prosthetic device to use:

Significantly, skin-sparing mastectomy allows the reconstructive surgeon to focus on how best to replace the glandular volume without the restraint of providing donor skin of similar color and texture. The question of which reconstructive technique to use has also become more complex and the emphasis is now on choosing the appropriate procedure for each patient. The current surgical repertoire comprises prosthetic techniques using tissue expanders and implants, and numerous autologous tissue flaps, including pedicled flaps, free tissue transfers, and perforator flaps.

With the discovery of genetic markers of breast cancer risk, the demand and indications for prophylactic mastectomy have increased. Furthermore, patients are rightfully adamant that their choices include procedures with reduced operative time and postoperative recovery. To meet these challenges, potential techniques needed to provide a combined, single-stage approach for both the mastectomy and the reconstruction. For many patients, the benefit of using a prosthetic approach is the simplicity of the procedures as well as the avoidance of distant donor-site morbidity. The advantages of a single, direct-to-implant operation, particularly in the patient needing prophylactic mastectomy, became obvious, and such operations have developed into a viable alternative to the other, more established reconstructive techniques. However, the surgical indications are specific and should be thoroughly familiar to both the surgeon and patient before selecting this direct to implant option.

Consultation for Direct-to-Implant Surgery

A comprehensive consultation with the patient before surgery is essential. This initial meeting provides the opportunity to review the risks and benefits of all reconstructive options as well as establishing candidacy for the direct-to-implant technique. This determination is directly related to the patient’s body habitus, the ablative nature of the surgery, and the specific desires of the patient for contralateral breast symmetry. Patients who are able to have skin-sparing or nipple areola–sparing mastectomies are prime candidates. In addition, expectations must be reviewed and a realistic understanding of the pros and cons of the surgery established.

Indications for Direct-to-Implant Technique

Skin-sparing mastectomy is indicated in most patients with breast cancer who are also planning for immediate reconstruction. Prophylactic mastectomy may be offered to patients who present with a high risk with or without genetic markers for developing breast cancer or for the patient who is considering prophylactic mastectomy on the opposite breast. In either situation, a direct-to-implant technique can be used.

The ideal candidate for the direct-to-implant technique is a woman with a medium or smaller breast size, grade 1 to 2 ptosis, and good skin quality. Patients with a history of smoking are required to abstain for 4 weeks before and after surgery. Morbidly obese patients are generally poor candidates for implant reconstruction and are usually better served by an autologous option.

Contraindications to the Direct-to-Implant Technique

There are few contraindications to the direct-to-implant technique.

Considerations in patients undergoing radiation therapy

An important consideration is how to proceed in the setting of radiation therapy. If the patient has received prior postlumpectomy radiation treatment and the skin changes are severe with a firm and nonexpansive skin envelope, it is our practice to recommend autologous tissue reconstruction. In our experience with those patients who have mild skin changes after receiving radiation therapy in the past, the chance of a vascular incorporation of the ADM in the radiated skin milieu is good, with an excellent indication for a successful outcome. A total of 40 patients in our series have received either preoperative or postoperative radiation treatments with no occurrence of capsular contracture, implant exposure, or infection requiring treatment.

In patients who are scheduled to receive adjuvant radiation therapy and who have declined an autologous tissue option, it is our practice to consider placement of a tissue expander in lieu of an implant. A pectoralis-ADM covering is created in the usual fashion. Expansion is performed rapidly with the goal volume reached before the initiation of the radiation treatment.

Skin viability

If there is any doubt as to the preoperative condition or intraoperative viability of the skin, then the procedure should be modified and an expander placed in the submuscular ADM pocket. A sufficient volume can then be injected into the expander; just enough to gently fill the skin envelope (hand-in-glove fit). In this way, skin tension can be avoided and filling of the expander can be performed once the skin has healed sufficiently.

In the past year, we have incorporated the use of intraoperative angiographic intravenous injection with the SPY (LifeCell Corp.) to assess the viability of the skin flaps after mastectomy and then after placement of the device. We have found that this technique not only provides instant feedback for the general/oncologic surgeon but also to the plastic surgeon who may see the effects of both the surgery and implant device on the overlying skin. The use of this technique in approximately 100 consecutive cases has predicted the final results.

Prophylactic mastectomy

A special consideration must be made for those patients presenting for prophylactic mastectomy who also desire a significant reduction in their breast size. In this situation, we do not recommend a nipple-sparing approach, because the viability of the nipple-areolar complex may be tenuous in the setting of a skin-reducing pattern or inverted-T incision. Skin pattern reduction, either vertical or Wise patterned, can be offered and used. Free nipple grafting has been performed in carefully selected settings with good outcome, but is subject to nipple loss from poor vascularity.

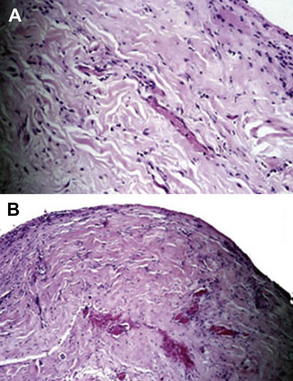

Preoperative Planning for Breast Implantation

As stated previously, the quality of the skin flaps after mastectomy is a critical component for a successful outcome. Choosing the appropriately sized implant to fill the space beneath these flaps is also an important consideration. See the algorithm in Fig. 2.

We do not routinely recommend saline implants because they often produce an inadequate aesthetic shape and are prone to greater visibility and palpability.

There are many types of ADM available on the market today. See Tables 1 and 2 for the allogenic and xenogenic biomaterials available now for breast reconstruction. The 2 major sources of skin use either a human or porcine model that is cleaved of cells and processed to create a framework of collagen into which cells can migrate.

Table 1 Allogenic biologic materials currently available for breast reconstruction

| Name | Company | Source Tissue |

|---|---|---|

| DermaMatrix® | MTF(Synthes) | Allograft |

| Flex HD® | MTF(Ethicon) | Allograft |

| NeoForm® | Tutogen(Mentor) | Allograft |

| AlloDerm® | LifeCell | Allograft |

Table 2 Xenogenic biologic materials currently available for breast reconstruction

| Name | Company | Source Tissue |

|---|---|---|

| Strattice™ | LifeCell | Xenograft |

| SurgiMend® | TEI Biosciences | Xenograft |

| Veritas® | Synovis | Xenograft |

The excellent experience with this graft in a wide range of soft tissue procedures has supported the rationale for its use in the postmastectomy setting where an inadequate muscular coverage exists. The potential for revascularization varies with both the source and thickness of the material. However, these materials have been used extensively throughout the body, significantly in abdominal wall and head and neck reconstruction.

Direct-to-implant technique

It is our practice to interact closely with the oncologic breast surgeons and provide assistance in advance of and during the mastectomy. We strongly believe that there is a need for the plastic surgeon to be an active participant in the ablative surgery, thereby assuring the careful handling of the skin and the avoidance of traction injury to the flaps. This careful handling can minimize the stretching and distortion that can occur with retraction as well as lowering the risk of ischemic injury. If electrocautery is used for flap elevation, low settings are monitored to reduce the risk of tissue damage. The use of scalpel dissection or, more recently, radiofrequency devices (Peak Surgical, Palo Alto, CA, USA) for skin flap development is encouraged.

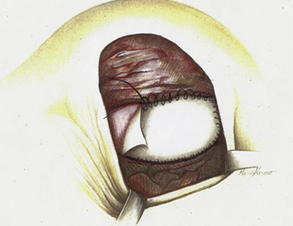

Using ADM to extend the submuscular plane, support the implant in its anatomic position, and define the inferior and lateral folds of the breast is critical for immediate reconstruction with the direct-to-implant technique. The operative concept was developed in 2001 and has proved to be successful in most cases.

Fig. 3 Retropectoral pocket and raising of pectoralis muscle to allow insertion of implant and AlloDerm® placement to cover reconstructed breast and allow closure of skin flaps.

Fig. 4 Running sutures are used to secure the graft to the elevated lateral border of the pectoralis major on one side and to the serratus anterior muscle on the other side.

(From Salzberg A. Non expansive immediate breast reconstruction using human acellular tissue matrix graft (AlloDerm). Ann Plast Surg 2006;57:1, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; with permission.)

This technique has withstood the test of time, with patients’ long-term results yielding little change in the last 10 years.

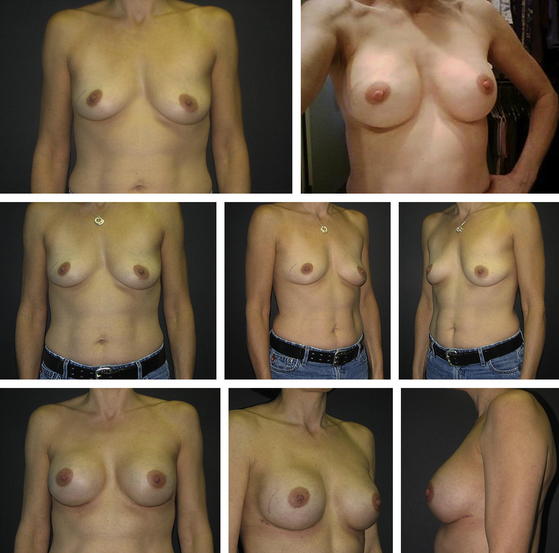

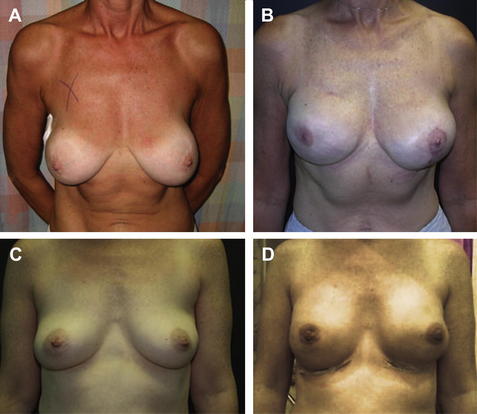

Figs. 5 and 6 show examples of patients before and after surgery.

Fig. 5 (Left) preoperative and (right) postoperative views of the breasts following immediate direct-to-implant reconstruction with ADM.

Fig. 6 Preoperative and postoperative views of the breasts of two women following immediate reconstruction supported by AlloDerm® grafting show good symmetry and desired breast projection. (A) Preoperative. (B) At 3 months after surgery. (C) Preoperative. (D) At 1 week after surgery.

Postoperative Care for Breast Implant Surgery

Typically, the patient remains in the hospital for approximately 48 hours. On discharge, the drains, which are covered with Bio-Patch (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) and occlusive dressings, are maintained for 7 to 14 days, with removal determined by the amount and quality of their output. A supportive surgical bra with an additional superior pole pectoralis strap is worn for 3 to 6 weeks to assist in the optimal positioning of the implants in the pocket. The patients are encouraged to perform moderate exercise to improve their arm range of motion, and to perform gentle massaging to prevent the development of axillary contracture.

Discussion on Breast Implant Technique

The selection of a breast reconstruction technique depends on individual patients’ anatomy as well as their preferences. In general, the choice has been either autologous tissue transfer; usually the TRAM (transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous) flap or the expander-implant approach. Although these techniques represent significant advances in the management of the postmastectomy patient, they are not without limitations and complications. Autologous tissue reconstruction has the concern of donor-site morbidity; the expansion patient must commit to multiple visits to the physician’s office for saline injections and, when the inflation is complete, a second surgical procedure is needed to replace the expander with a permanent implant (or, if a combination implant device is used, to remove the filling port).

Skin-sparing technique

In the past 10 years, skin-sparing techniques have allowed surgical oncologists to spare more skin, preserve muscle fascia, and perform nipple-sparing prophylactic surgery for high-risk or early stage patients. With the advent of the skin-sparing mastectomy, plastic surgeons have been given the opportunity to take advantage of the aesthetic benefits bestowed by an intact skin envelope. In addition, the placement of an ADM in continuity with the pectoralis muscle establishes implant support and permits the projection that is essential for a natural breast contour.

Tissue expanders

Traditionally, a tissue expander is used when there is a need to increase the surface area of the breast skin. In addition, the expander is placed below the pectoralis muscle to assure sufficient soft tissue coverage of the implant. After the subsequent exchange procedure, this coverage reduces implant palpability and visibility, and maintains a protective barrier between the implant and skin. The routine use of tissue substitutes to cover expanders has now become a useful supplement and the attachment of incorporated ADM to the pectoralis muscle can provide a durable line of defense against thin skin flaps and potential exposure.

Direct to implant with ADM

The technique of direct-to-implant reconstruction with ADM has expanded the surgeon’s repertoire and given the patient an opportunity to have a 1-stage option (in a nipple-sparing mastectomy) that was previously available only when using autologous tissue. This alternative has become particularly attractive to young women with a genetic disposition to breast cancer. Those with insufficient available tissue for a flap can elect to undergo a nipple-sparing mastectomy combined with the direct-to-implant approach. We find that an inframammary approach to prophylactic mastectomy is reliable and gives the best cosmetic result. This technique affords patients the opportunity to receive a reconstruction with as little external scarring as possible (Fig. 7).

Personal experience with direct-to-implant reconstruction began in 2001 and now includes approximately 700 immediate direct-to-implant breast reconstructions in 460 patients. Before this, the expander-implant technique was, in most cases, the method of choice for immediate, prosthetic breast reconstruction. That approach allowed the available tissue coverage to be slowly increased for effective mound replacement. Incorporating ADM now provides additional coverage at the serratus/pectoralis muscle interval and allows the immediate creation of the breast mound. The technique produces total implant coverage without the need for expansion, repetitive surgeries, and delayed return of normal body image. The success observed with the direct to implant with ADM technique indicates the effectiveness of the procedure as well as the long-term safety and aesthetic benefits of the approach.

The direct to implant with ADM technique has created a paradigm shift allowing postmastectomy breasts to resemble the results achieved with aesthetic augmentation. With the ability to define the surgical implant pocket, support the device in the proper position, and reduce postoperative visits and the need for a secondary surgery, a new reality has been achieved. The use of a biologic product that is incorporated into the patient’s own tissue ensures the benefits of regenerative medicine and eliminates encapsulation of nonbiologic material.

Suggested readings

A.K. Alderman, E.G. Wilkins, H.M. Kim, et al. Complications in postmastectomy breast reconstruction: two year results of the Michigan breast reconstruction outcome study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2265.

R.H. Ashikari, A.Y. Ashikari, P.R. Kelemen, et al. Subcutaneous mastectomy and immediate reconstruction for prevention of breast cancer for high-risk patients. Breast Cancer. 2008;15(3):185-191.

D.C. Birdsell, H. Jenkins, H. Berkel. Breast cancer diagnosis and survival in women with and without breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92(5):795-800.

C. Dean, U. Chetty, A.P. Forrest. Effects of immediate breast reconstruction on psychosocial morbidity after mastectomy. Lancet. 1983;1:459-462.

D.I. Duncan. Correction of implant rippling using allograft dermis. Aesthet Surg J. 2001;21(1):81-84.

R.D. Foster, L.J. Esserman, J.P. Anthony, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective cohort study for the treatment of advanced stages of breast carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:462-466.

J. Gibney. The long-term results of tissue expansion for breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1987;14:509-518.

J.M. Gryskiewicz, R.J. Rohrich, B.J. Regan. The use of AlloDerm for the correction of nasal contour deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:561.

W. Halstead. The results of operations for the cure of cancer of the breast performed at The Johns Hopkins Hospital from June 1889 to January 1894. Johns Hopkins Bull. 1894;4:297.

C.H. Johnson, J.A. Van Heerden, J.H. Donohue, et al. Oncological aspects of immediate breast reconstruction following mastectomy for malignancy. Arch Surg. 1989;124:819-824.

F.R. Jones, B.M. Schwartz, P. Silverstein. Use of a nonimmunogenic acellular dermal allograft for soft tissue augmentation: a preliminary report. Aesthet Surg J. 1996;16:196-201.

S.S. Kroll, F. Ames, S.E. Singletary, et al. The oncologic risks of skin preservation at mastectomy when combined with immediate reconstruction of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;172:17-20.

S.S. Kroll, J.A. CoffeyJr., R.J. Winn, et al. A comparison of factors affecting aesthetic outcomes of TRAM flap breast reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:860-864.

S.S. Kroll, M.A. Schusterman, H.E. Tadjalli, et al. Risk of recurrence after treatment of early breast cancer with skin-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:193-197.

A. Losken, G.W. Carlson, J. BostwickIII, et al. Trends in unilateral breast reconstruction and management of the contralateral breast: the Emory experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:89-97.

N.G. Menon, E.D. Rodriguez, C.K. Byrnes, et al. Revascularization of human acellular dermis in full-thickness abdominal wall reconstruction in the rabbit model. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;50:523.

M.J. Miller. Immediate breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1998;25:145-156.

R.J. Rohrich, B.J. Regan, W.P. Adams, et al. Early results of vermilion lip augmentation using acellular allogeneic dermis: an adjunct in facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:409-417.

C.A. Salzberg. Nonexpansive immediate breast reconstruction using human acellular tissue matrix graft (AlloDerm). Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57(1):707-711.

K.W. Spencer. Significance of the breast to the individual and society. Plast Surg Nurs. 1996;16:131-132.

L.A. Stevens, M.H. McGrath, R.G. Druss, et al. The psychological impact of immediate breast reconstruction for women with early breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:619-628.

A.J. Stolier, J. Wang. Terminal duct lobular units are scarce in the nipple: implications for prophylactic nipple-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(2):438-442.

E.O. Terino. AlloDerm acellular dermal graft: applications in aesthetic and reconstructive soft tissue augmentation. In: A.W. Klein, editor. Tissue augmentation in clinical practice. Marcel Dekker; 1998:349-377.

D. Wainwright, M. Madden, A. Luterman, et al. Clinical evaluation of an acellular allograft dermal matrix in full-thickness burns. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17:124-136.

D. Wainwright. Use of an acellular allograft dermal matrix (AlloDerm) in the management of full-thickness burns. Burns. 1995;21:243-248.

D.K. Wellisch, W.S. Schain, R.B. Noone, et al. Psychosocial correlates of immediate versus delayed breast reconstruction. Am J Psychol. 1985;76:713-718.