Acellular Dermal Matrices in Breast Surgery: Tips and Pearls

Abstract

Acellular dermal matrices (ADMs) have been used for postmastectomy breast reconstruction, primary and secondary breast augmentation, and reduction mammaplasty. In postmastectomy breast reconstruction, ADMs can be used to either create an implant pocket in single-stage reconstruction or to create the inferolateral portion of the tissue expander pocket in two-stage reconstruction. Specific deformities after cosmetic breast augmentation such as contour irregularities and implant malposition can be addressed with ADMs. The use of ADMs is a safe alternative for the correction of breast deformities after reconstructive and aesthetic breast surgery.

Keywords

• Acellular dermal matrices • Breast reconstruction • Surgical techniques

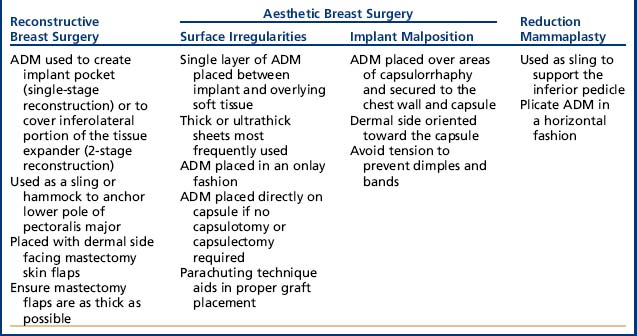

Acellular dermal matrices (ADMs) have been used for postmastectomy breast reconstruction, primary and secondary breast augmentation, and reduction mammaplasty.1,2 In postmastectomy breast reconstruction, ADMs can be used either to create an implant pocket in single-stage reconstruction or to create the inferolateral portion of the tissue expander pocket in 2-stage reconstruction. Specific deformities after cosmetic breast augmentation such as contour irregularities and implant malposition can be addressed with ADMs (Table 1).1 The benefits of using ADMs include a low complication rate, the ability to provide needed tissue, and the ability to aid in repositioning the implant (Table 2). The disadvantages include the risk of infection and seroma, and high cost. The use of ADMs is a safe alternative for the correction of breast deformities after reconstructive and aesthetic breast surgery.

Overview of ADMS in breast surgery

ADMs became available in 1994 and the most commonly used ADMs in breast surgery are AlloDerm® (LifeCell, Branchburg, NJ, USA), Strattice™ (LifeCell Corporation, Branchburg, NJ, USA), DermaMatrix® (MTF/Synthes CMF, West Chester, PA, USA) and FlexHD® (Ethicon, New Brunswick, NJ, USA).

AlloDerm® regenerative tissue matrix is produced by removing the epidermis and cells from human cadaveric skin.3 Strattice™ reconstructive tissue matrix (LifeCell Corp., Branchburg, NJ, USA) is derived from porcine dermis denuded of cells and sterilized using electron beam irradiation.4 DermaMatrix® (MTF/Synthes CMF, West Chester, PA, USA) is human skin in which both the epidermis and dermis are removed from the subcutaneous layer of tissue in a process using sodium chloride solution, rendering it sterile and preserving the original dermal collagen matrix.5 FlexHD® acellular hydrated dermis is derived from donated human allograft skin.6

ADM Biomechanical Differences

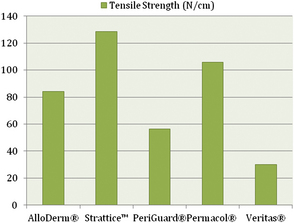

A few biomechanical differences that are of clinical relevance exist between the various ADMs. AlloDerm® has been reported to have increased elasticity compared with DermaMatrix®7 and Strattice™.8 This quality is relevant in situations in which increased elasticity is preferred, such as in addressing capsular contracture, or when the goal is for the ADM to conform to the inferolateral curvature of the breast.7 When the ADM is needed to provide support, such as in repositioning a displaced implant, a less elastic ADM like Strattice™ is preferred.8 Figs. 1-3 provide a comparison of the different biomechanical properties of various types of biologic meshes.

ADM Size

When deciding on the size of ADM to use, the patient is assessed preoperatively, and any surface irregularities or implant malposition are marked with the patient standing, sitting, lying down, and flexing the pectoralis major muscles. These markings aid in choosing the size of the ADM to be used.1 Intraoperatively, the sheet of ADM is fashioned to the appropriate size of defect at the time of placement. With respect to the sizes of ADM to use, a 4-cm × 16-cm piece of AlloDerm®9-11 is typically used; the thickness of ADM varies from 1.3 to 1.8 mm, and the thickness used depends on the indication. Spear and colleagues12 devised a guideline for selection of AlloDerm® size based on the arc length of the inframammary fold and the lateral mammary fold; for arc lengths of 18 cm or less, Spear and colleagues advocate a thick piece of 4 × 12 cm. For arc length greater than 18 cm, they advocate a thick piece of 4 × 16 cm.

ADM Preparation

In terms of preparation of the ADM, the matrix is hydrated in saline as instructed by the manufacturer. Different hydration times are required depending on the product; AlloDerm® requires at least 30 minutes of rehydration before its application3 but DermaMatrix® can be rehydrated in 3 minutes.5 It is important to examine the ADMs for dermal elements, such as hair, and to remove them if present. Sterile technique must be used when handling ADMs. The dermal matrix is handled by only 1 surgeon, after either changing or cleansing the gloves. The product is taken from the saline bath where it is soaking and placed directly in the wound so that it does not contact the operative field or the patient’s skin.13

ADM Placement

The ADM has a distinct polarity, and this must be identified intraoperatively. The dermal side has a smooth, shiny appearance that seems to absorb blood that it contacts. This side should be placed in contact with the underside of the mastectomy flap because it has been shown to be more likely to revascularize.14 In addition, the dermal side is potentially more seroma forming, and is thus kept away from the implant. The basement membrane side is dull and rough in appearance, and seems to repel blood that it contacts. This side is placed down so that it contacts the implant.13 It is important to avoid layering the ADM material because it is an avascular foreign body and this can increase the risk of infection and seroma formation.1 For postoperative care, soft compression and a surgical bra postoperatively may be helpful in minimizing dead space.13 Patients should remain on antibiotics to cover gram-positive skin flora for a 7-day period.

Uses of ADMS in breast reconstruction

Between one-half and two-thirds of women undergoing postmastectomy breast reconstruction choose alloplastic reconstruction, which makes prosthesis-based reconstruction the most common method of reconstruction in these patients.15 After mastectomy, an implant16 or a tissue expander is placed underneath the pectoralis major muscle, and the muscle covers the superior and medial poles of the prosthesis. The exposed inferior and lateral poles can be covered with subcutaneous tissue or by elevating serratus anterior or pectoralis minor muscles17; however, incomplete or inadequate coverage of the prosthesis can result in a higher risk of visible rippling, implant visibility or exposure, and contour irregularities.7,11,14,18 Some patients have a deficiency of the soft tissue envelope because of either an atrophic pectoralis major, its native insertion site on the chest wall, or because of intraoperative trauma or resection during the course of the mastectomy.19

ADMs are a solution to this problem because they can be used either to create the implant pocket in single-stage reconstruction or to maintain the inferolateral portion of the tissue expander pocket in 2-stage reconstruction (Fig. 4).20 After the mastectomy has been performed, a subpectoral pocket is developed. The boundaries of this pocket are the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle to the second rib superiorly, the sternum medially, and the level of the contralateral inframammary fold inferiorly.21 The inferior attachment of the pectoralis major muscle is dissected from the chest wall.22

Various techniques have been described to attach the ADM to local tissue. See Box 1 for some technique tips for using ADMs in breast reconstruction.

Box 1 Technique tips for using ADM in breast reconstruction

Benefits of using ADMs in postmastectomy reconstruction include

These factors can potentially improve aesthetic outcomes.10,20,21,25

ADMs can also augment the perfusion of a vulnerable skin envelope11 by offloading the mechanical stress caused by the implant weight on the skin envelope and the skin closure.26

Using ADMs can reduce the time needed for the entire reconstructive process by reducing the time or need for tissue expansion; in turn, this concept can expedite the start of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation if needed. By limiting the amount of dissection during implant or expander placement, using ADMs may decrease postoperative pain.25

Uses of ADMS in aesthetic breast surgery

Compared with the literature on postmastectomy reconstruction, there are fewer data on the uses of ADMs in cosmetic breast surgery. Despite this paucity of literature, there are unique challenges to be addressed in revision surgery of the augmented breast:

Two categories of problems to correct with revision aesthetic breast surgery are surface irregularities and implant malposition.

Use of ADMS to correct surface irregularities

Postoperative surface irregularities can include rippling or wrinkling, bulging, or capsular contracture.

Rippling is often an inherent feature of saline implants and is more obvious when the implant is covered with a thin soft tissue envelope.27 In addition, tissue expansion often results in some degree of thinning of the overlying tissues, even with submuscular placement.27

Fig. 5 Use of ADMs for secondary deformities in breast reconstruction (preoperative and postoperative).

ADMS Versus Fat Grafting

Although autologous fat injections are gaining popularity as a method of correcting contour deformities, compared with ADMs they have several disadvantages:

In addition, long-term data of fat grafting to the native breast are lacking. There are early reports that are now evaluating the impact of breast cancer surveillance with fat grafting.

Use of ADMS to correct implant malposition

Implant malposition can occur as a result of capsular contracture or with malposition of the inframammary fold with or without bottoming out of the lower pole.29 A variety of methods have been used to correct capsular contracture, including using a combination of capsulorrhaphy and marionette sutures.9,29 Another method involves changing the implant pocket from a subglandular to dual-plane position with the addition of an ADM graft; the graft is fixed to the pectoralis major muscle, to the perichondrium of the rib cage, and to the serratus anterior muscle flap.29,30

Symmastia can result from excessive release of the medial origins of the pectoralis major muscles, resulting in medial displacement of the implants. It occurs when implants are placed too close to the midline or when an iatrogenic communication occurs. One management option involves performing a medial capsulorrhaphy and then suturing the soft tissue to the sternum. The posterior capsule can be dissected from the rib cage and rolled up if subpectoral implants were used. These procedures have been met with variable degrees of success and are prone to failure because of the difficulty of separating the capsular pockets.31 To correct implant malposition in symmastia, the ADM may be placed over areas of capsulorrhaphy and secured to the chest wall and capsule: the short edge of the AlloDerm® is sutured directly to the displaced fold and then redraped over the capsule of the breast.32 An ADM can also be used as a medial, C-shaped sling that is created between the 2 implants.31 A graft of AlloDerm® is sutured to the rib periosteum inferiorly and draped in a C-shaped fashion superiorly to the anterior capsule.31

ADMs are secured with 3.0 Vicryl (Ethicon Inc, Somerville, NJ, USA) or Monocryl (Ethicon Inc, Somerville, NJ, USA). Only a few tacking sutures are needed in most cases; however, in the correction of symmastia, more sutures may be required to secure the ADM and avoid permanent suture dimpling of the skin. Tension should be avoided because surface dimples and bands can occur.

Use of ADMS in reduction mammaplasty

A common postoperative finding in inferior pedicle breast reduction is an upward rotation of the nipple-areola complex and descent of the breast parenchyma, otherwise called star-gazing or bottoming out. This finding occurs because of recurrent skin laxity. In attempting to address this issue, Brown and colleagues2 devised an approach in which AlloDerm® could be used as a sling to support the inferior pedicle and hence prevent this unwanted breast deformity. These investigators describe using an ADM as an “internal brassiere” for support of the pedicle. To help gain a better cosmetic outcome in terms of nipple-areola position and breast projection, the pedicle superior to the ADM was plicated in a horizontal fashion in addition to suturing AlloDerm® to the chest wall as a sling. In the postoperative period, no nipple loss was noted, and 2 patients developed complications; 1 had partial flap necrosis and the other had cellulitis. No bottoming out was seen in any of the patients.

Complications with ADMS

The use of ADMs does not seem to significantly increase the risk of postoperative complications33 but is not without risk.

Microbial Contamination

AlloDerm® is the most widely used ADM product, and when tested to confirm the absence of microbial contamination, it is not terminally sterile.17 Because AlloDerm® comes from a human donor, there is a risk of transmitting communicable diseases such as viral hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (although there have been no such reported cases). The product meets the standards of tissue banking and donor screening established by the American Association of Tissue Banking and the US Food and Drug Administration.1

Infection

In the last few years, studies have been published that compare the complication rates of postmastectomy reconstruction using prostheses with or without AlloDerm®. Only 1 of these studies34 reported a statistically significant increase in infection and 1 study reported an increased seroma rate in the AlloDerm® group.17 As ADM recellularizes, revascularizes, and becomes incorporated into the host tissue, it has the potential to overcome infection. However, it takes time for the ADM to recellularize and revascularize, providing a window in which infection can occur.35 In an animal model, Eppley36 observed that rolled or multilayered ADM revascularized more slowly or, in some areas, not at all when compared with a single flat sheet of ADM. This finding indicates that potential rolling or bunching of ADM can lead to poor vascularization, with an increased risk of infection.36 When the ADM comes in contact with the nipple-areola complex, it may be exposed to contamination from Staphylococcus species, which can be abundant in the distal mammary ducts. Therefore, it is best to avoid ADM placement in this region.1

Radiation Tolerance

There is ongoing debate about the ability of ADMs to tolerate exposure to radiation. Studies that have compared complications in irradiated and nonirradiated breasts have indicated a higher rate of complications in irradiated versus nonirradiated breasts.

However, overall, the risk of infection did not vary with or without AlloDerm®.

Rawlani and colleagues37 found that the overall complication rate in irradiated breasts was 30.8% (compared with 13.7% in nonirradiated breasts, P = .0749). Despite this higher rate of complications, ADM-assisted tissue expander reconstruction seems to resist radiation effects more than plain tissue expander reconstructions,12,37,38 or at least have a similar rate of complications.19

Diagnostic Dilemmas

There has been a report of a potential diagnostic dilemma, with ADM mimicking a new breast mass in a patient who had had a previous mastectomy.39 ADMs can undergo reactive inflammatory changes and be confused as masses within the breast, especially with the minimal subcutaneous fat in this area and with thin mastectomy skin flaps. Patients should be informed that ADM use in breast surgery can lead to induration, palpable scarring, and the potential need for further diagnostic studies.39 With the sophisticated imaging available, it seems that the appearance of ADMs is different from and does not mask recurrences on either a mammogram or a magnetic resonance imaging scan of the breast.40

Outcomes with ADMS

In a retrospective study by Hartzell and colleagues,1 a single surgeon’s experience using ADMs after breast augmentation from 2005 to 2009 was analyzed:

After their revision procedures using an ADM

In 78 consecutive patients who underwent revisionary breast augmentation/mastopexies with ADM

These data suggest that, with the use of ADMs, the capsular contracture rate after secondary augmentation and augmentation mastopexy procedures may be reduced.38

Basu and colleagues41 found that when compared with native breast capsules, ADM had lower levels of inflammatory parameters:

AlloDerm® decreases radiation-related inflammation and delays or diminishes pseudoepithelium formation and thus may slow progression of capsular formation, fibrosis, and contraction.42 These findings suggest that ADM may show certain properties that may reduce formation of a capsule and therefore provide an alternative to total submuscular implant placement in breast reconstruction procedures.41,43

Costs of ADMs

One of the drawbacks to the use of ADMs is their cost. A 6-cm × 16-cm thick AlloDerm® sheet cost $3463 (USD) per sheet as of January 2010 (Jansen; economic analysis).44 However, direct-to-implant reconstruction with AlloDerm® was found to be less expensive than 2-stage non-AlloDerm® reconstruction.44 Strattice™ is less expensive than AlloDerm®. In addition, Strattice™ is available in specific sizes and shapes to reduce cost and minimize waste.8

Summary

ADMs have many applications in breast surgery. In addition to postmastectomy breast reconstruction, ADMs may be safe to use with a limited number of complications in the setting of contour deformities after cosmetic breast operations. The 1 drawback is that they are expensive.44 The use of ADMs is a safe alternative for the correction of breast deformities after reconstructive and aesthetic surgery. Appropriate patient selection, operative technique, and postoperative management are crucial in successful application of ADMs to breast surgery.

References

1. T.L. Hartzell, A.H. Taghinia, J. Chang, et al. The use of human acellular dermal matrix for the correction of secondary deformities after breast augmentation: results and costs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(5):1711-1720.

2. R.H. Brown, S. Izaddoost, J.M. Bullocks. Preventing the “bottoming out” and “star-gazing” phenomena in inferior pedicle breast reduction with an acellular dermal matrix internal brassiere. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34(6):760-767.

3. LifeCell. Breast reconstruction. 2011. Available at: http://www.lifecell.com/strattice-reconstructive-tissue-matrix/255/. Accessed December 7, 2011.

4. LifeCell. KCI’s LifeCell Granted CE Mark for its Strattice(R) Reconstructive Tissue Matrix. 2008. Available at: http://www.kci1.com/cs/Satellite?c=KCI_News_C&childpagename=KCI1%2FKCILayout&cid=1229631881542&pagename=KCI1Wrapper. Accessed December 7, 2011.

5. Synthes. DermaMatrix Acellular Dermis. Human dermal collagen matrix. 2006. Available at: http://www.synthes.com/MediaBin/US%20DATA/Product%20Support%20Materials/Brochures/CMF/MXBRODermaMatrixAcellular-J7237D.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2011.

6. MTF. FlexHD Acellular Hydrated Dermis. 2006. Available at: http://www.mtf.org/professional/flex_hd.html. Accessed December 7, 2011.

7. S. Becker, M. Saint-Cyr, C. Wong, et al. AlloDerm versus DermaMatrix in immediate expander-based breast reconstruction: a preliminary comparison of complication profiles and material compliance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(1):1-6. [discussion: 107–8]

8. M.Y. Nahabedian. AlloDerm performance in the setting of prosthetic breast surgery, infection, and irradiation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(6):1743-1753.

9. K.H. Breuing, S.M. Warren. Immediate bilateral breast reconstruction with implants and inferolateral AlloDerm slings. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(3):232-239.

10. G.M. Gamboa-Bobadilla. Implant breast reconstruction using acellular dermal matrix. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56(1):22-25.

11. R.J. Zienowicz, E. Karacaoglu. Implant-based breast reconstruction with allograft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(2):373-381.

12. S.L. Spear, P.M. Parikh, E. Reisin, et al. Acellular dermis-assisted breast reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32(3):418-425.

13. H. Sbitany. Techniques to reduce seroma and infection in acellular dermis-assisted prosthetic breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(3):1121-1122. [author reply: 1122]

14. J.D. Namnoum. Expander/implant reconstruction with AlloDerm: recent experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):387-394.

15. G.M. Le, C.D. O’Malley, S.L. Glaser, et al. Breast implants following mastectomy in women with early-stage breast cancer: prevalence and impact on survival. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(2):R184-R193.

16. M. Askari, M.J. Cohen, P.H. Grossman, et al. The use of acellular dermal matrix in release of burn contracture scars in the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(4):1593-1599.

17. A.S. Liu, H.K. Kao, R.G. Reish, et al. Postoperative complications in prosthesis-based breast reconstruction using acellular dermal matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(5):1755-1762.

18. A.S. Colwell, K.H. Breuing. Improving shape and symmetry in mastopexy with autologous or cadaveric dermal slings. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61(2):138-142.

19. V. Bindingnavele, M. Gaon, K.S. Ota, et al. Use of acellular cadaveric dermis and tissue expansion in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(11):1214-1218.

20. L.A. Jansen, S.A. Macadam. The use of AlloDerm in postmastectomy alloplastic breast reconstruction: part I. A systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(6):2232-2244.

21. C.A. Salzberg, A.Y. Ashikari, R.M. Koch, et al. An 8-year experience of direct-to-implant immediate breast reconstruction using human acellular dermal matrix (AlloDerm). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):514-524.

22. S.T. Lanier, E.D. Wang, J.J. Chen, et al. The effect of acellular dermal matrix use on complication rates in tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(5):674-678.

23. K.H. Breuing, A.S. Colwell. Inferolateral AlloDerm hammock for implant coverage in breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(3):250-255.

24. D.I. Duncan. Correction of implant rippling using allograft dermis. Aesthet Surg J. 2001;21(1):81-84.

25. B.M. Topol, E.F. Dalton, T. Ponn, et al. Immediate single-stage breast reconstruction using implants and human acellular dermal tissue matrix with adjustment of the lower pole of the breast to reduce unwanted lift. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61(5):494-499.

26. E.C. Liao, K.H. Breuing. Breast mound salvage using vacuum-assisted closure device as bridge to reconstruction with inferolateral AlloDerm hammock. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(2):218-224.

27. R.A. Baxter. Intracapsular allogenic dermal grafts for breast implant-related problems. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(6):1692-1696. [discussion: 1697–8]

28. H. Hyakusoku, R. Ogawa, S. Ono, et al. Complications after autologous fat injection to the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(1):360-370. [discussion: 371–2]

29. S.L. Spear, M. Seruya, M.W. Clemens, et al. Acellular dermal matrix for the treatment and prevention of implant-associated breast deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(3):1047-1058.

30. M.M. Mofid, N.K. Singh. Pocket conversion made easy: a simple technique using alloderm to convert subglandular breast implants to the dual-plane position. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29(1):12-18.

31. M.S. Curtis, F. Mahmood, M.D. Nguyen, et al. Use of AlloDerm for correction of symmastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(4):192e-193e.

32. M.Y. Nahabedian. Discussion. The use of human acellular dermal matrix for the correction of secondary deformities after breast augmentation: results and costs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(5):1721-1722.

33. B.A. Preminger, C.M. McCarthy, Q.Y. Hu, et al. The influence of AlloDerm on expander dynamics and complications in the setting of immediate tissue expander/implant reconstruction: a matched-cohort study. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60(5):510-513.

34. Y.S. Chun, K. Verma, H. Rosen, et al. Implant-based breast reconstruction using acellular dermal matrix and the risk of postoperative complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(2):429-436.

35. T. Isken, M. Onyedi, H. Izmirli, et al. Abdominal fascial flaps for providing total implant coverage in one-stage breast reconstruction: an autologous solution. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(6):853-858.

36. B.L. Eppley. Experimental assessment of the revascularization of acellular human dermis for soft-tissue augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(3):757-762.

37. V. Rawlani, D.W. Buck2nd, S.A. Johnson, et al. Tissue expander breast reconstruction using prehydrated human acellular dermis. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66(6):593-597.

38. G.P. Maxwell, A. Gabriel. Use of the acellular dermal matrix in revisionary aesthetic breast surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29(6):485-493.

39. D.W. Buck2nd, K. Heyer, J.D. Wayne, et al. Diagnostic dilemma: acellular dermis mimicking a breast mass after immediate tissue expander breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(1):174e-176e.

40. H.S. Tran Cao, C. Tokin, J. Konop, et al. A preliminary report on the clinical experience with AlloDerm in breast reconstruction and its radiologic appearance. Am Surg. 2010;76(10):1123-1126.

41. C.B. Basu, M. Leong, M.J. Hicks. Acellular cadaveric dermis decreases the inflammatory response in capsule formation in reconstructive breast surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(6):1842-1847.

42. E. Komorowska-Timek, K.C. Oberg, T.A. Timek, et al. The effect of AlloDerm envelopes on periprosthetic capsule formation with and without radiation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(3):807-816.

43. C.A. Salzberg. Nonexpansive immediate breast reconstruction using human acellular tissue matrix graft (AlloDerm). Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57(1):1-5.

44. L.A. Jansen, S.A. Macadam. The use of AlloDerm in postmastectomy alloplastic breast reconstruction: part II. A cost analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(6):2245-2254.