Of the clients who have sought my help with anxiety, without exception, the ones who have progressed the fastest and gained the most control over their anxiety are those who have been willing to do the work between sessions at home and on a daily basis.

Those who take on board – and take responsibility for – the process of owning and managing their anxiety and are willing to incorporate the learnings and techniques from our sessions into their everyday lives are always the ones who will reap the fullest benefits of this work.

To do the work, we need the tools. This chapter is the first of four throughout the book that will introduce you to the contents of your Anxiety Toolbox – which will be an invaluable resource as you take control of the problem of anxiety in your life.

The Toolbox – Parts I, II, III and IV – will bring together some of the strategies and techniques that have proven most effective and most useful to both myself and my clients over the years in managing anxiety.

In this chapter, we will look at the tools and strategies of mastery, the daily check-in, writing your thoughts and playing with the timeframe.

In the same way that the experience of anxiety itself plays out differently for each of us, each of these tools may resonate differently with you – and what works well for one person, may not for another. So it’s a good idea to try them out, and pick and choose those that best suit you as an individual and the way you prefer to work.

When you have built some awareness of what areas in your life are most dominated by anxiety and have some tools to help you in this work, it’s time for action!

Managing our expectations

This first tool is actually a way of thinking – a mindset – rather than a practical technique.

When I initially came across it in my own personal journey, it instantly clicked with me and made sense of why I always seemed to start so many things but never saw them through. I have also found that it has greatly helped many of my clients to take a more measured approach to managing their anxiety, enabling them to relax into a process that they could be forgiven for wanting to rush.

Many of us have had the experience of starting new things – the gym, learning a foreign language, yoga, online courses, piano lessons, and so on – only to find that, after the initial burst of enthusiasm, we just as quickly lose interest and give them up. What’s happening here is that we want to change something – usually an unwanted, recurring feeling – and the exciting new venture does exactly that – initially. It gives us a quick jolt of, ‘This is what life is all about!’, and then reality kicks in as the new activity becomes difficult, mundane, too time-consuming or generally a hassle.

When we are looking to do work on ourselves, this same pattern – the initial enthusiasm followed by a slump in interest and motivation – can be especially evident. This is where unrealistic standards and expectations of constant progress can stop us achieving our goals. More and more, we look for the quickest way to get what we want. The thought of something taking large amounts of our time and commitment is off-putting. We want to be good at the new skill the minute we start – and if we are not, we don’t see the point of trying at all. If we are anxious or a worrier, then sticking with a commitment may be difficult, as we can’t be sure how things will turn out. There is nothing that feeds uncertainty, and therefore worry, like not progressing as well as we think we should be.

Driven by our own standards of how we think we should be performing, we can have a belief that we must always be visibly progressing, and, when we are not, this can feel very defeating. It’s the feeling of not progressing that can make us quit and this, in turn, can lead us to think badly of ourselves, as our thoughts turn to how useless we are and how inevitable failure always is for us.

What many of us don’t understand, however, is that progress is hard to measure accurately if we are just using how we feel we are doing as our gauge.

In his bestselling book, Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-term Fulfilment, George Leonard, the renowned US author and educator, outlines what real progress towards being good at something difficult and worthwhile actually looks like. When learning anything, the initial burst from ‘zero’ – no knowledge or ability – to ‘knowing something’ can be quick and thrilling. If we are learning to play a musical instrument, for example, being able to put together a few notes can give us a buzz of excitement and the feeling that anything is possible. The learning process becomes more problematic, however, when we expect this upward trajectory to continue at the same rate and our progress to look like the line below.

What we expect mastery to look like.

As we continue with our learning, however, the excitement swiftly diminishes, and we are faced with the reality of the journey ahead of us. As the initial fun, our keenness to learn and the sense of novelty begin to fade, we quickly realise that things are not going to be easy.

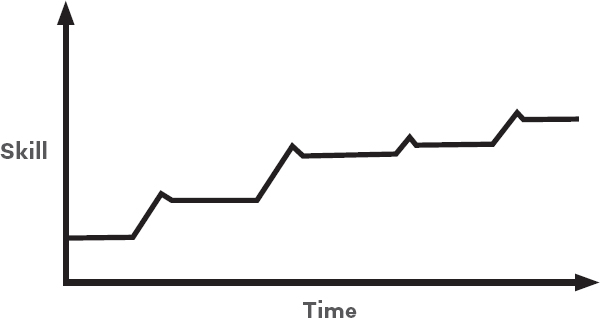

Leonard believes that mastering any new skill involves short, sharp bursts of progress, each of which is followed by a slight dip and then a plateau for a certain period of time. Real progress, he argues, is gradual. It can feel slow, sticky and boring at times. Yes, there are moments when progress is tangible, but most of the time we are in practice mode – so the real progress curve, Leonard asserts, will look more like the line on this page.

In this diagram, there is still an overall, upward trajectory, but most of our time is spent on the plateau, churning through the mundane, repetitive and sometimes unsatisfactory work, until we get to the next spike, after which our progress tapers off again.

What real mastery looks like.

The plateau can get a bad rap in society today. We are made to feel that if we are not constantly achieving, winning and taking big strides forward, we are not focused enough or simply not working hard enough. However, the truth is that, in this type of work as in many others, we have to pay our dues on the plateau to be able to make any strides at all. The ‘winning’ is a tiny moment in time. The plateau is the constant.

If we start something new or set ourselves a goal, we want to experience continuous, visible progress. If we don’t, we feel like we’re failing – and it is this feeling that can cause us to quit. But giving up on our goals can have a detrimental effect on our mental wellbeing. Much of our positive emotion around achievement comes from being able to see that we are moving towards a goal. And if we don’t have any goals, we are denying ourselves so many opportunities for feeling a positive sense of achievement.

When learning anything that is difficult, and therefore worthwhile, we have also to learn to embrace setbacks as part of the journey and be able to tolerate life on the inevitable plateau. In fact, the plateau is where the real work happens, this is the work that enables the next jump in our learning. As Leonard puts it in Mastery: ‘You practice diligently, but you practice primarily for the sake of practice itself.’

If we get caught up in the need for visible progress, then we will be disappointed and will be more likely to give up.

If we think of any goal we’ve achieved in our lives, we will see the truth of this. Nothing worthwhile is ever achieved instantly or painlessly. When we reach our goal, there is a momentary high, but then there is tomorrow and the next day. So, in this sense, the high is fleeting anyway. Life moves on. Very soon, we need a new goal and, to achieve it, we must also force ourselves to take the sometimes laborious, sometimes boring but always necessary steps along the way.

It is, however, on the way to the goal that life is lived. The slow progression can give us an enormous feeling of satisfaction but only if we can let go of the need to see constant progress.

Mastery in context

If we take our working lives, for example, we can see that progress in the workplace operates in the same way. There may be new jobs, new roles, promotions and so on, dotted throughout but, in the main, we are on the plateau. Not as in, ‘Oh no, my career is plateauing!’, but the place where we just knuckle down and get on with our jobs. We have an eye on our goals but, mainly, we are simply doing the work.

Since we often don’t realise the impact we are having in our workplace, we can presume that what we are doing is going unnoticed. We don’t feel like we are progressing. What we need to do here is to allow ourselves to learn, practise and become proficient in what we do. As we have already said, achieving real, tangible goals requires a lot of work that is mundane and unassuming. We are not always going to be the standout person in the room.

When it comes to anxiety, it can work the same way. With the initial awareness and the decision to take concrete action, there is often a positive, buoyant feeling. Soon, however, this learning process becomes like every other, requiring practice, patience, persistence and time spent on the plateau, honing our tools. With this kind of work, allowing ourselves to feel comfortable on the plateau is crucially important because of the sheer strength of feeling anxiety can cause. Those who live with anxiety want the feeling gone, and quickly – but this is not how this process works. Managing anxiety is something we need to incorporate into our lives, even when it feels like we are not making any progress. If we can keep in mind Leonard’s principle of mastery, where the skill we are mastering is the ability to manage our anxiety, it will be so much easier for us to knuckle down for the long term and accept that the most worthwhile goals always involve time, setbacks and commitment.

Daily check-in

If we’ve been habitually ignoring difficult emotions for as long as we can remember, how we are feeling and thinking may often be a mystery to us. The tendency to operate in a hazy fog is something worriers may be very familiar with, as they try to do battle with thoughts they’d rather they weren’t having. However, before we can do any useful work in managing anxiety, and our mental health in general, it is crucial for us to be able to pin down our thoughts and emotions with as much clarity as possible.

Asking yourself how you are and how the day has gone is a good practice to build into your daily life, and can have a three-fold benefit. Firstly, particularly at the beginning of this work, it will give you a sense of what is and isn’t helping when it comes to the strategies you are trying out to better manage your anxiety. Secondly, keeping in touch with your inner self in this way will help you build the capacity to address or let go of difficult thoughts, and to deal with any painful emotions that need addressing directly. Thirdly, over time, a daily check-in will help you realise that facing how you are feeling is not as scary as you perhaps once believed it was.

Making this check-in or review part of your daily routine doesn’t need to be a big deal – you just ask yourself a few simple questions, so you know if you are in good shape or if you need to do a bit of work. Anchoring your check-ins to something you do every day as a matter of course can be really helpful, as piggybacking on an existing habitual event makes the check-in easier to remember and incorporate into your daily routine. Something that has worked very well for me and my clients has been to use morning and evening tooth-brushing sessions for this purpose. We tend to brush our teeth on autopilot, and it is something that we know we will be doing at least twice a day. It’s also an activity that offers the perfect brief window of time for a quick check-in. Of course, if you find something that works better for you, then go for it! Perhaps it could be during your commute to work or while eating your lunch or as you wait for the kettle to boil for your usual afternoon cup of tea – whatever is best for you.

For example, in the morning as you brush your teeth, simply ask yourself how you are. How do I feel today? What have I been saying to myself since I woke up? Is there anything I’ve been mulling over in my head that needs to be brought into the light or is there a persistent thought that I need to just acknowledge and let go of?

When you brush your teeth at night, it’s a similar routine. How am I now, just before bed? How did today go? Was there anything that caused me any difficulty that I need to address quickly? Is there anything I did today to tackle my anxiety, and was it helpful? Do I have anything on my mind that is likely to affect my sleep?

This check-in does not need to become a huge burden, where we drag up all sorts of unwanted feelings. It’s just a brief check-in. If we think there is something that needs further examination, we can set aside time later in the day (or the following day) to address it more closely. Then, at the designated time, we can see if the feeling is still as intense or if we can just let it go.

We go about all of this in the same way we would if we woke up with a sore throat. We wouldn’t immediately presume we were sick and needed to reach for medication – we’d wait a couple of hours, and possibly put it down to how we’d slept. If then we felt better later in the day, we could afford to just ignore it on this occasion. If, on the other hand, the pain remained, then we’d probably need take a closer look. So, if there is something that pops up in the check-in, we can write it down if necessary, give it the morning, or sleep on it, and see if the troubling thoughts or emotions linger. The check-in should not extend beyond the boundaries of the daily process we have anchored it to.

In Chapter 6 (Anxiety Toolbox II), we will look at how to address the common types of thought that tend to come up for us, but, for now, it is enough to use our daily check-in to get a general sense of what is going on for us. The idea is that we are getting more comfortable with asking ourselves how we are, and are not too afraid of the answer.

Writing to think

Sometimes, in a therapeutic setting, people are fully engaged and speaking fluently about things that have happened to them or about thoughts they have had about the previous session. More often though, people look off into the distance, reaching into their thoughts and tentatively saying words they hope make sense. They are thinking, and the act of talking out the thoughts helps them formulate what they really mean or feel. They are often surprised at what emerges, since they weren’t previously aware that they had these thoughts or that the thoughts in question had such a depth of feeling behind them. It’s an amazing process to be part of and, in those moments, a therapist will stay out of the client’s way as best they can. Any interjection at that stage can pollute the process, taking the person out of their thoughts or leading them to add details or reflections that do not belong there.

Writing down our thoughts can afford us a similar opportunity to slow down for a moment, focus our minds and aid the thinking process. This can be such a powerful tool. When we are stuck in our thoughts of worry or anxiety, we can go around in circles for hours without any kind of resolution. It’s often only after we get the thoughts out of our heads that we realise what is really going on. Writing down our thoughts can do this for us and give us a clarity that we cannot get through thinking alone.

So, especially at times when anxiety or worry seems to be taking over, try writing down what is going on in your mind. At the very least, it will slow down your thinking and provide some perspective. You can then read over what you have written and look at it more objectively, which can spark another stream of thoughts.

Next, you can analyse how you are thinking or step back from your thoughts and come up with solutions or input that may have been unavailable to you earlier. As you read your own words, you can try to come at them from another perspective entirely. What would I say to another person who had written this? What advice would I have? Would I understand what they were going through? Would I be sympathetic to their situation?

As you are writing, try free association. Just write whatever words come to mind. Nobody else will be reading what you write. You don’t need to censor yourself or worry about punctuation, grammar or spelling. Simply try to write about what you are feeling at that moment – your hopes and fears. It is OK to not know what to write – just put down whatever your brain says. If it bores you, write about being bored and see where you end up. If you think it’s a stupid exercise, write about what it feels like to be wasting your own time … Just write, and follow where the pen takes you.

In Chapter 6 (Anxiety Toolbox II), we will be looking at a process to enable us more direction in dealing with and challenging some of our thoughts, but, for now, writing freely is a simple process to help us think. Keep it simple and stay out of your own way.

Playing with the timeframe

Playing with the timeframe of our thinking is a really good way to get more control over worry. Sometimes, our thoughts are so far off into the future that they lose all sense of reality, yet they still fill us with dread. At other times, we are so closely focused on how we feel in the present moment that we lose sight of the bigger picture showing how we are doing overall. In the first scenario, the future worry can be all-consuming; in the second, the moment-to-moment feelings can be overwhelming.

If we are at work and have a project or a large, complex task to deal with, we can often race off in our thoughts to a time days, weeks or months down the road, and a scenario where we have failed miserably to get the work over the line – people are angry, our reputation is damaged and our current job and future job prospects are in jeopardy. Here, we are completely underestimating our own ability to cope and risk getting seriously stuck in this future worry.

At such times, what our brains need more than anything is to observe us starting and making progress. With the making of progress, our worry lessens and our brains turn down the critical warning signals. Unfortunately, however, worry and anxiety can make it difficult to start anything, as the uncertainty becomes too much to handle. So, we put off starting anything, and if we continue to do this, we will end up proving to our brains that it was right to worry!

This is where the timeframe in our minds needs to be seriously pulled in. When we catch ourselves worrying about things too far ahead into the future, we need to call out the thought (‘future worry’), and calmly bring ourselves back to the present moment. When in the present, we then make a deal with ourselves on how far ahead our worrying thoughts are allowed to go: ‘I’m just going to deal with the next two hours. Anything beyond that is not something I can control. I’m going to live with the uncertainty and deal with starting this task.’

Now, these aren’t magic words and your brain will probably still head off down the worry road, but you keep reining things in. Every time you catch your worry running farther ahead than it needs to, you do not engage with those ‘future thoughts’ and you gently guide your mind back with compassion and without judgement.

Picture a puppy straying farther away from you than feels safe. Pick him up, bring him back, rub his little head and tell him, ‘Just stay close to me for the next while, as I finish what I’m doing just now.’ If you don’t like dogs, use whatever imagery works best for you! What is important is that you have a relaxed sense of control over the timeline and you stay, as best you can, inside the boundary you’ve set yourself.

When it comes to how we are feeling, we sometimes need to pan out and see a larger timeframe. This is especially useful if we are particularly intolerant of feeling uncomfortable emotions or if we tend to make the fact that we are having a difficult time mean something about our futures.

When we are feeling low or anxious, it can often be difficult to get out of this frame of mind, but playing with the timeline is really worth trying. If we are having a bad few hours or days, and our worry feels particularly intense, it is very helpful to pull back and ask ourselves how the past week or month has gone. OK, perhaps this particular day hasn’t gone great, but maybe the week overall has been good. So, this can offer the perspective that things are not going as badly as we think at that moment, and also give us a sense of the impermanence of any particular mood or emotion.

To help with this tool of expanding the timeframe of our thinking, it can be useful to start tracking our daily moods. We can do this in a simple paper diary, or use technology in the form of a mood tracking app, of which there are many. The advantage of the technology option is that we can visualise a timeframe much more easily. We can often look back and think that we’ve had awful week in terms of worry because negative emotions tend be more difficult to deal with and stay longer in our memories. A bad bout of worrying before bed can risk clouding an entire day that may have been perfectly fine. We can easily forget that the week had many good moments or had full days when we felt fine. If we make note of our moods every evening before bed, we have really helpful data to use when we are not in a great moment. This tracking should only take thirty seconds, with just a few words – the more cumbersome it becomes, the less likely we are to do it.

Playing with the timeframe of our internal dialogue when things are difficult can be a really effective tool. If a worrisome thought hits us and gets our anxiety going, we can ask ourselves why we are feeling this way now. If we were perfectly fine twenty minutes ago, and nothing has changed, why are we letting this thought dictate how we feel now?

So, we pull the timeframe right back and refuse to engage in anything too far into the future. Using this technique in conjunction with some of the tools in Chapter 6 can help us to distance ourselves from these unconstructive future thoughts and not get too caught up in some of our more difficult thinking patterns.