12

NOT THAT!

“So, Alfie,” my dad says at dinner that night as he helps himself to some rice. “Give us your report.”

See, our family has this dinner tradition my mom and dad call “civilized conversation,” where each person says the best and worst thing that happened to them that day.

Of course, I have not been telling the truth about my worst things ever since Jared and Stanley started picking on me for no reason a couple of weeks ago.

Alfie twiddles one of her braids, thinking. “Well, my good things are that Suzette wants to be my friend again, and I painted a beautiful picture about a flower,” she finally announces.

Suzette is that bossy little girl in my sister’s day care, remember?

“You’re supposed to choose just one good thing,” I tell Alfie, because rules are rules.

And what is the point of a tradition if you do the rules wrong?

“I can choose two things if I want,” she tells me, scowling. “Are you saying my beautiful flower picture isn’t good?”

“No, he’s not saying that, Alfie,” my mom says in her calm-down voice. “What was your worst thing, honey?”

Alfie scowls, which makes her look like an angry kitten. This is probably not the effect she was hoping for. “My worst thing was when my brother was mean to me at dinner,” she tells us.

“All right, then,” my dad says. “Moving right along. What about you, Louise?”

It’s no fair that my mom and dad have normal names like Louise and Warren when my sister and I get stuck with Alfleta and Lancelot Raymond.

Mom pats her lips with her napkin and looks up at the ceiling. “My good news is that I got a nice rejection letter today for that book I wrote about the enchanted princess who lives in the undersea kingdom,” she tells us.

Okay. Now that is just sad, because “rejection” means “no,” no matter how good you try to make it sound.

I feel like punching those rejection guys in the nose for insulting my mom!

But instead, I eat another bite of chicken and stare hard at my plate, because one of our rules is that you can’t argue about another person’s good and bad.

“What did the letter say?” my dad asks.

“That they wanted to see more of my work in the future,” Mom tells him, smiling. She looks shy but proud. “And my bad news is that I left the ice cream out on the counter by accident when I got home from the store,” she confesses.

There goes dessert, which is bad news for everyone.

“And what about you, son?” Dad asks.

Did I mention that he is still wearing his tie, even though it’s just us?

I have been silently rehearsing my answer for the last ten minutes. “My best thing is that I told about the layers of soil in the experiment without messing up,” I report. “And the worst—”

“What about the layers of soil?” Dad asks, leaning forward as if this is the most interesting thing he has heard all night—which it probably is, because he likes rocks and crystals and minerals better than anything in the world, except us.

“Well,” I say, trying hard to remember, “one jar had lots of sand in it, and Ms. Sanchez said that sample was from the desert. And another jar had mostly silt, and that was from some river. And one jar was the perfect mix of sand and silt and clay, which means you could grow stuff in it, Ms. Sanchez said.”

“Excellent, EllRay,” Dad tells me, beaming. “And what was the worst thing that happened to you today?”

“I dropped my sandwich at lunch,” I lie.

Dad looks at me, and his eyes look extra-big behind his glasses. “And that’s it?” he asks. “That is absolutely the worst thing that happened to you today?”

I can feel my ears getting hot. “Yes sir,” I lie again.

“Then I need to speak to you after dinner, son,” Dad says, his voice changing from curious to serious in one second flat. “In my office.”

My mom clears her throat, and Alfie looks at me with big sad eyes, like she’s feeling really, really sorry for me.

UH—OH.

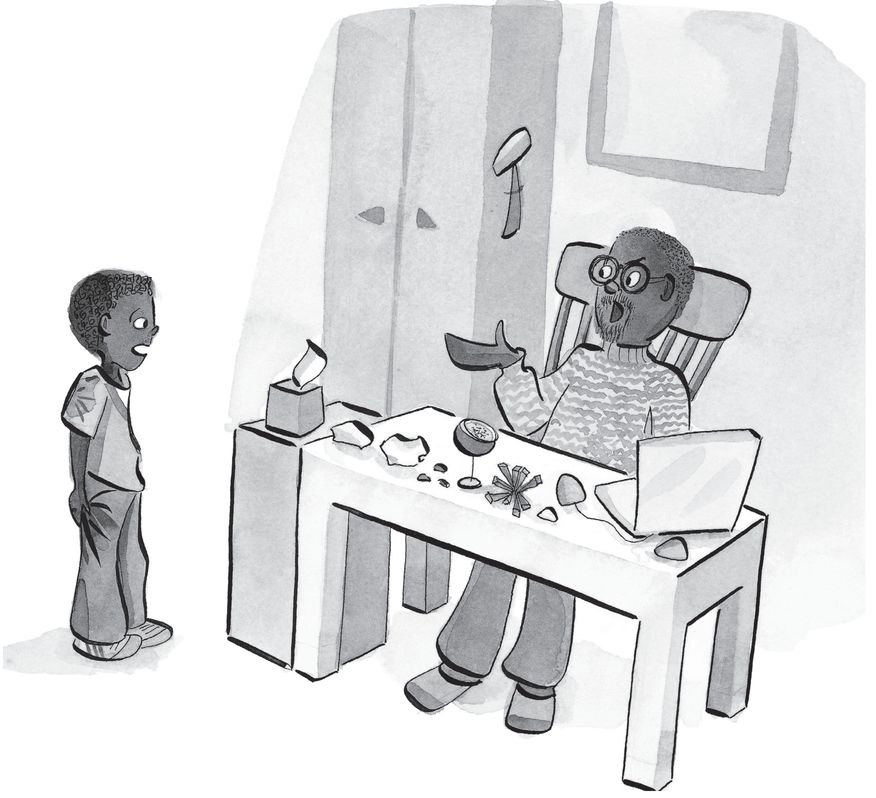

My father is sitting behind his shiny desk, only now he looks like Dr. Warren Jakes, not Dad.

I close the door behind me and listen to the sound of my heart pounding in my ears.

It’s no fair to have bad things happen to you at school and at home.

It should be one place—at the very most.

I’m not even sure what I have done wrong that my dad is so mad about. It could be so many things!

1. For instance, I didn’t brush my teeth this morning, even though I wet my toothbrush so my mom would think I did.

2. And I pulled my bedspread up over the wrinkled sheet and blanket this morning without really making my bed.

3. And I wore a T-shirt that was in the dirty clothes hamper, because I didn’t like any of the shirts that were clean.

“Ms. Sanchez called,” my dad says. “Just before dinner.”

He waits.

This telephone conference thing has gone too far.

And why did she pretend she didn’t know who was causing that bad vibe?

“But I didn’t behave wrong,” I say in a croaky, guilty-sounding voice.

I don’t even mention Disneyland, because I don’t want to give my dad any ideas about canceling our trip. He is the strict kind of dad who might do that.

“I know,” my dad says, frowning. “But Ms. Sanchez told me you fell down in class, and she says Jared Matthews might have tripped you on purpose. She wasn’t sure, because her back was turned.”

I hold my breath and don’t say a word.

“Did he trip you, son?” Dad asks gently. “Is there something going on at Oak Glen that we should know about?”

Okay.

When we moved to Oak Glen three years ago, my mom and dad were a little worried, because there aren’t that many other families in this town who are African-American. Just about ten or eleven of them, something like that. And at first, my parents were on the lookout for any little thing that would tell them people had some problem with us. But so far, so good—except sometimes I wish there were more black kids at our school, just so it would come out even.

Oh, and Alfie told me once that Suzette at day care keeps wanting to touch her braids. But that’s a secret, we decided, because we don’t want our dad to freak.

He’s very sensitive about stuff like that.

“No, nothing,” I mumble. “It’s okay.”

“Speak up, son,” my dad reminds me. “Be proud of what you have to say.”

“I am proud,” I tell him, even though my heart is thudding so hard you can almost see my T-shirt jump. “But Jared tripped me by accident, Dad. Accidents happen, right? That’s where the expression comes from.”

Sure, I could get Jared in trouble right now by telling on him.

Sure, I could even say he’s picking on me because I’m black.

But it’s not that! Jared would have said something if it was. He is not the type of kid to keep things to himself. That much is obvious.

Anyway, there are plenty of other things that could be make him want to pick on me. Like, I’m the shortest kid in class, so I’m the easiest to pick on.

And I get all the laughs, so maybe he’s jealous.

In fact, I’m better at just about everything at school—except being big—than Jared is.

Or, like I said before, there could be no reason at all. Just him being bored because Christmas is over.

“And you’re really all right?” my dad asks, looking me up and down—which doesn’t take very much time at all, for obvious reasons.

I nod my head.

“But—why didn’t you mention it to your mom or me, EllRay?” Dad asks. “I just don’t understand. I certainly think falling flat on your face in class is a worse thing than dropping your sandwich at lunch.”

“But dropping my sandwich meant I was hungry all afternoon,” I explain, still lying my head off. “And you’re not supposed to argue about another person’s good or bad,” I remind him, even though I probably shouldn’t.

Dad sighs. “Well, you have a point there,” he finally admits. “But I want you to promise that you’ll tell your mother or me if this problem with Jared continues, okay? Because we want to nip this sort of thing in the bud.”

I’m not exactly sure what that expression means, but I get the general idea. “I promise,” I tell him, crossing my fingers behind my back.

I don’t like lying to my dad, but in this case, it’s for his own good.

Also, it’s for the good of Disneyland.

I think I’ll go on the pirate ride first.

“Can I leave now?” I ask. “Because I have homework to do, and I don’t want to get behind.”

My father looks at me for one long minute. Behind his glasses, his brown eyes still look troubled. “All right, son,” he says slowly. “If you’re sure everything is really okay at school.”

“It is,” I tell him. But I pause with my hand on the doorknob and look back. “Thanks, Dad,” I say, because all of a sudden, for the very first time, it occurs to me that it is probably hard for him to be him, just the way it’s hard for me to be me. He’s so prickly and proud, and then he’s got all those rocks to lug around.

Maybe it’s hard for him, anyway.