The Biggest Thing on Earth

The Biggest Thing on Earth

Up at the dam, everybody was young, everybody was crazy.

—ARNO HARDEN

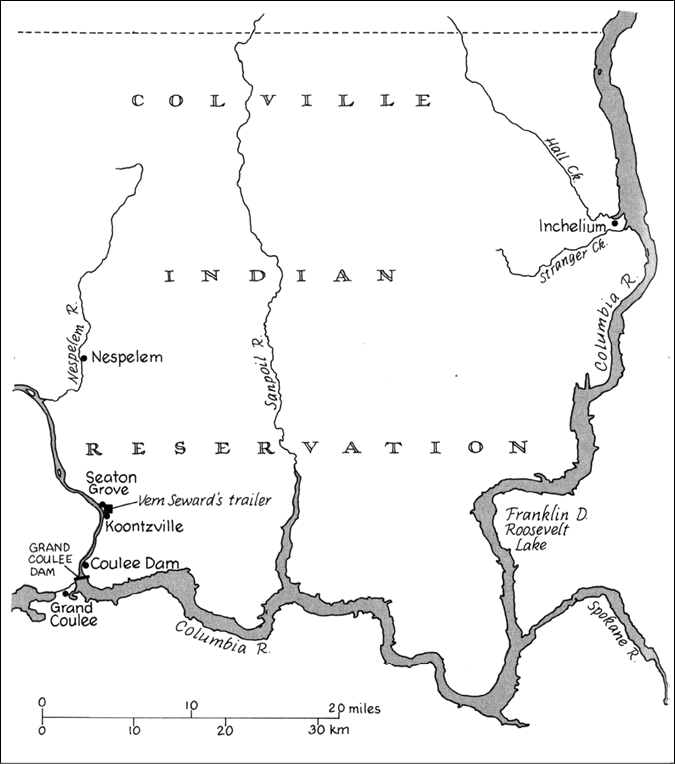

THERE WERE ABOUT four thousand men working at Grand Coulee Dam in early 1936, with hundreds more streaming in every month. A favored few found family housing in carefully planned, all-electric communities down in the mile-wide canyon where the dam was going up. In Engineer’s Town and Mason City, the families of government engineers and senior employees of the contractor had indoor toilets and shade trees, flower-growing contests and rules about drinking. The unfavored majority, men without women, pitched up at a distance from the shade, the plumbing, and the rules. The working stiffs, as they called themselves, lived beyond the east lip of the canyon in the municipality of Grand Coulee, a boomtown that had the longest line of brothels the West had seen since the Gold Rush. It was the cesspool of the New Deal, the Sodom and Gomorrah of the engineered West. Dam workers lived in boardinghouses, tents, cars, caves, and the boxes that dance-hall pianos came in.

My father hitched a ride upriver to Grand Coulee in the late spring of that year after losing his apple-loading job in Wenatchee. He and his younger brother, Albert, found jobs as broom-and-bucket men down in the bowels of the emerging dam. They lived in a two-room shack not far from B Street.

Both sides of B Street were oiled with card sharks, moonshiners, pool hustlers, pickpockets, dope peddlers, professional piano players, pimps, and a limited number of women who, like everybody else, had come to town for money. B Street was unpaved and had no sidewalks. It was gluey mud in the winter, choking dust in the summer, live music all night long. The town of Grand Coulee was born the year after Prohibition ended. In six loutish years, it was credited with having soaked up more alcohol per square foot than any town in the state of Washington.

My father and his brother frequented the Silver Dollar, an unpainted, false-fronted B Street saloon, where an ex-con named Whitey Shannon employed fifteen dime-a-dance girls. Ill-mannered men who wanted to do more than dance with these girls were tossed out by a bartender named Big Jack. There was a sweet-voiced crooner named Curly who looked and sang like Gene Autry, and between numbers a skinny kid would shovel away the dirt that fell on the dance floor from dam workers’ boots.

“At Whitey Shannon’s place, the girls stood around like at any other dance. But when you go up and ask if she wanted to dance, she first held out her hand, palm up. If you give her a dime, away you go,” my father told me. “These were pretty nice girls, the ones at the Silver Dollar. Hell, they made a fortune. So did ol’ Whitey Shannon. The fighting was mostly out in the street. There was quite a lot of fighting. Well, you know, there was bound to be. That many men together and a lot of drinking. It was mostly over women. There weren’t many women up there, and what was there didn’t always behave. Me and my brother didn’t go to B Street very much. It was pretty rough. There was shootings and knifings and all that stuff. There was a guy I saw shot just as you go through town. He run off with someone’s wife or some damn thing.”

Mary Oaks, chief telephone operator at the dam, took calls from B Street nearly every night: “The owners would say we got a dead man over here and would you call the police. If they weren’t dead, of course, they would want a doctor.” Trucks with loudspeakers tooled up and down B Street, urging workers to make less noise and refrain from activities that might spread social diseases. Dr. George Sparling, head of the Grand Coulee office of the Washington State Health Department, announced—somewhat desperately—that “everyone found with disease will be sent to the county jail . . . and kept there until cured.” State Patrolman Francis McGinn found a number of dam workers unconscious in the alley behind B Street. They told him, when they woke up, that bartenders had laced their drinks with knockout drops and stolen their wallets.

It was not just working stiffs who took their pleasure on B Street. Harvey Slocum, chief foreman for the main contractor at the dam, favored the liquor and the girls at a B Street brothel called Swanee Rooms. The second-floor whorehouse got too hot for Slocum one summer. So he dispatched a government-paid plumbing crew from the dam site to put sprinklers on the brothel’s roof. It was Grand Coulee’s first air-conditioning system. When Slocum got fired for his assorted sins, the Wenatchee World reported the reason as “ill-health.” Slocum later dressed down the reporter who wrote the story. “You put in that goddamn paper of yours that I was canned because of ill-health. Now you know damn well I got canned because I was drunk.”

Grand Coulee Dam made everyone in the Pacific Northwest a bit drunk. The dam was an intoxicating cocktail of engineering genius, Depression-era chutzpah, and western myth. Larger than any structure ever built in world history, it was a Paul Bunyan story come true. It seemed to prove what westerners had always been taught to believe about themselves. They were a special people who could dream their way out of trouble, who could combine a good idea with elbow grease and overcome calamities as shattering as the Great Depression, as threatening as World War II.

Going into the project, the boosters of Grand Coulee Dam had had no shortage of gall. They proposed building the planet’s largest dam, at taxpayers’ expense, in a desolate American outback that had more jackrabbits than human beings. It was to be “the biggest thing on earth.” What they ended up creating—with the unexpected coming of World War II—was something even bigger, an eye-popping metaphor for Manifest Destiny. It was vaccine for the Great Depression and a club to whip Hitler, a dynamo to power the dawn of the Atomic Age and a fist to smash the monopolistic greed of private utilities, a magnet for industry and a fountainhead for irrigated agriculture. The dam was a mixed metaphor with enough concrete in it to lay a sixteen-foot-wide highway from New York City to Seattle to Los Angeles and back to New York.*

Grand Coulee Dam validated the notion that God made the West so Americans could conquer its natural resources, that He made the Columbia River so they could dam it up, extract electricity, and divert it into concrete ditches.

It was made-to-order for the New Deal, President Roosevelt’s grab bag of deficit-spending schemes to rescue America from the Depression. Big enough to make headlines across the country, it quickly created more than seven thousand jobs. For Roosevelt, the dam—with its promise of affordable power for the working classes—had the added political advantage of infuriating private utilities and the Republican Party. The president personally approved the sixty-three-million-dollar emergency grant that jump-started work at the dam in 1933. And Roosevelt himself headed up what became a public-relations extravaganza to justify the dam as a showpiece for the New Deal. Twice the president visited a dust-blown construction site that in the continental United States could hardly have been farther away from the White House or more inconvenient to get to, especially for a man disabled by polio.

Even in Washington State, the dam was not an easy destination. It was stuck out in coulee country, 240 miles east across the Cascades from Seattle, 90 miles west of Spokane. Work had hardly begun when Roosevelt, having traversed Washington State by riverboat, train, and car, first arrived on a hot August day in 1934. He was ridiculously early. There was nothing to see except holes in the ground. No matter. Roosevelt had come not to inspect, but to cheer. Not the dam, but his idea of building it.

“We are going to see with our own eyes electricity made so cheap that it will become a standard article of use not only for manufacturing but for every home,” he said. “I know that this [empty desert] country is going to be filled with the homes not only of a great many people from this state, but by a great many families from other states of the Union—men, women, and children who will be making an honest livelihood and doing their best to live up to the American standard of living and the American standard of citizenship.”

Addressing several thousand Washington State residents who followed him out to the middle of nowhere, Roosevelt preached to the converted at the dam site. But his real audience was an army of unbelievers back East who were attacking Grand Coulee as “socialistic, impractical dam-foolishness.” Eastern members of Congress, the private power lobby, and the engineering establishment scoffed at the idea of generating record amounts of electricity and building a massive irrigation scheme in a corner of the country that had less than 3 percent of the American population. The president of the American Society of Civil Engineers said the dam was “a grandiose project of no more usefulness than the pyramids of Egypt.” Collier’s magazine wrote in 1935 that the dam’s reclamation scheme proposed irrigating a region of “dead land, bitter with alkali,” so hell-like that “even snakes and lizards shun it.”

After Roosevelt went back to Washington, publicists at the Bureau of Reclamation worked for years to drown out the dam’s critics. They did so with a deluge of press releases filled with facts about how fabulously big Grand Coulee was going to be. Its concrete would fill fifty thousand boxcars in a train more than five hundred miles long. It would make a concrete cube two and a half times taller than the Empire State Building. The Bureau of Reclamation built a replica of the dam, one-eightieth actual size, and sent it on a national tour. Hawking what it called the “Eighth Wonder of the World,” the Bureau produced films, published picture books, laid on bus tours, and built grandstands overlooking the dam site. They accommodated forty thousand tourists a month.

When Roosevelt returned to Grand Coulee in October of 1937 for another round of presidential cheerleading, he melded all the bigger-than-big Grand Coulee statistics into one all-encompassing American boast: “Superlatives do not count for anything,” Roosevelt said, “because [the dam] is so much bigger than anything ever tried before.”

While the Roosevelt administration managed to make Grand Coulee Dam a household name across America in the 1930s, it did not succeed in sanctifying the project as part of western mythology until 1941. That is when the federal government came up with the idea of paying a working-class icon $3,200 to write pro-dam propaganda. Woody Guthrie, the Dust Bowl poet and folk balladeer, visited the Columbia Basin for thirty days in a chauffeur-driven government car. Traveling between Bonneville Dam near Portland and Grand Coulee Dam, Guthrie wrote lyrics for twenty-six songs, most of them set to familiar folk melodies. Many of the songs were instantly forgettable, Bureau of Reclamation press releases dressed up in cornpone rhymes. Others were so bad they were hard to forget. In “The Song of the Grand Coulee Dam,” Guthrie wrote: “I’ll settle this land, boys, and work like a man, I’ll water my crops from Grand Coulee Dam. Grand Coulee Dam, boys, Grand Coulee Dam, I wish we had a lot more Grand Coulee Dams.”

But the best song, “Roll On Columbia, Roll On,” succeeded in ways that the publicists back in Washington could never approach. Blending the power of the river with myths about Manifest Destiny, Guthrie transformed Bureau of Reclamation concrete into proletarian glory.

Green Douglas firs where the waters cut through.

Down her wild mountains and canyons she flew.

Canadian Northwest to the ocean so blue.

Roll on, Columbia, roll on!

And on up the river is Grand Coulee Dam

The mightiest thing ever built by a man,

To run the great factories for old Uncle Sam;

It’s roll on, Columbia, roll on!

Roll on, Columbia, roll on!

Your power is turning our darkness to dawn,

So, roll on, Columbia, roll on!

When the United States entered World War II, the dam became a strategic treasure. Critics went silent. The Saturday Evening Post, in an article entitled “White Elephant Comes into Its Own,” said that America’s need for electricity “transformed the whole costly project of harnessing the latent power of the Columbia . . . from a magnificent day dream . . . into one of the best investments Uncle Sam has ever made.”

Electricity from the Columbia River—from Grand Coulee Dam and the much smaller Bonneville Dam—produced about one-third of the nation’s aluminum during the war. Grand Coulee generated the power that made half of America’s warplanes. B-17 Flying Fortress aircraft rolled off assembly lines at Boeing in Seattle at the rate of sixteen planes every twenty-four hours. In Portland, three shipyards relied on Grand Coulee’s power to make nearly 750 big ships. A “mystery load” of electricity (later revealed to be 55,000 kilowatts, more power than all of the electricity civilian consumers in the Northwest used in 1945) flowed from Grand Coulee to a secret tent city along the Columbia called Hanford.

President Harry S. Truman said in 1948 that without Grand Coulee and Bonneville Dams “it would have been almost impossible to win this war.” In the same year, Earl Warren, the future chief justice of the Supreme Court and then a Republican running for vice-president against Truman, said Grand Coulee had done nothing less than save America from atomic annihilation.

“Probably Hitler would have beaten us in atom bomb development if it had not been for the hydroelectric development of the Columbia, making possible the big Hanford project which brought forth the bomb.”*

At the beginning of The Dam, a popular history of Grand Coulee that was published in 1954, a young philosophy major from the University of Washington explained why he wanted to work at the dam: “There are parts of our culture that stink with phoniness. But we can do some wonderful things too. That dam is one of them. If our generation has anything good to offer history, it’s that dam. Why, the thing is going to be completely useful. It’s going to be a working pyramid.”

The pyramid had begun to rise in the river when my father was handed rubber boots, a rubber jacket, a broom, and a bucket and ordered to work about sixty feet below the surface of the Columbia.

A cofferdam, a temporary dike bulging out from the east bank of the Columbia, had diverted the river so that one edge of its bed could be cleaned of earth and rock. Excavators cut down to granite, 105 feet beneath the surface of the pushed-aside river. Tombstone polishers, using soap and water and hand-held brushes, had been brought in from around the Northwest to clean and buff the granite. When my father reported to work, the east corner of the dam had been built up about forty feet from the polished granite floor.

Dams rise from the bedrock of a river in a series of domino-shaped concrete pours. Before each new pour, laborers pick clean, hose down, and sandblast every surface. Unless hardened concrete is scoured clean, wet concrete might not adhere to it; there could be cracks and structural weakness. For fifty cents an hour, eight hours a day, six days a week, my father cleaned concrete, picking up loose rocks, bits of wire.

“I didn’t like that doggone work, down in that hole, pickin’ up those little rocks. You could hear the river gurgling on the other side of the cofferdam. It was a helluva thing. It was cool down there and it was wet.”

Grand Coulee is a gravity dam, meaning that its sheer weight holds back the river. Tall, graceful arch dams like Hoover or Glen Canyon hold back rivers by transferring their downstream force to the walls of high, narrow canyons. But the canyon where Grand Coulee Dam squats was too wide for an arch dam. It demanded a super-heavy gravity dam with lots of concrete, twelve million cubic yards of it, three times more concrete than Hoover Dam, more concrete in one place than ever before in history. It was poured in blocks, about five feet high and varying from thirty to fifty feet square. Block on top of block was poured as the dam climbed up from the bedrock. There was little that was novel about the building methods at Grand Coulee. It simply was much, much bigger.

After three months, my father considered his options in the dam-building profession and quit. He quit because he was bored and because he was uncomfortable down in the hole. He also quit because he did not want to get hurt. Fifteen men had already been killed at the dam. Another sixty or so would be killed as concrete was poured for four more years. They were mangled in conveyor belts, crushed by dropped buckets of concrete, blasted by dynamite, run over by trucks, drowned in the river, and dismembered in long falls. My father found a safer, more lucrative living, one that got him out of the hole and gave him an eye-opening angle on the wicked ways of B Street. He delivered milk.

He began his milk route every morning at 3 A.M., when the brothels on B Street were still accepting customers, the piano players were still playing, and liquored-up workers were still out wrestling in the mud.

“You know what was odd?” my father said. “Those chippy houses used a lot of milk. I guess they made drinks out of it. Maybe they bathed in it. I don’t know. I sold two cases a day to Swanee Rooms [where the chief foreman at the dam ordered government-paid plumbers to put sprinklers on the roof]. I sold milk to four of them brothels. But you know those prostitutes never in three years did me out of one dime. No sir, they never did. That is more than you can say about the rest of them up there.”

As the dam began to straddle the river, the payroll expanded to nearly eight thousand employees. More housing was built, and thousands of workers began to bring their wives up to the dam site. These young wives, almost none of whom were allowed to work at the dam or anywhere else, had very little to do. Many of them, after their husbands drove off to work at the dam, were stranded without transport in houses perched on barren hills above the dam. According to one memoir, which was written by a man, women were expected to bear their burdens in silence.

“At a gathering at the camp one day the resident wives were asked by the wives who had lived in the cities, ‘How can you live here? How can you be happy and get along?’

“ ‘Keep your bowels open and your mouth shut,’ was the sage advice.”

In his morning milk deliveries, my father found that not very many women lived up to expectations.

“You saw more stuff going on in these homes than you did in the cathouses. You wouldn’t believe the stuff that I seen. Some of these homes, these women, their men’s workin’, see. Hell, I got invited in their homes so many times. You wouldn’t believe what goes on in these homes, I’m telling you. They would come to the door, no damn clothes on, yeah they would.

“There was a place outside of town, it was a nice place, too, it was just getting daylight. I set the milk down and I looked up and they had an open porch there. There was a bed there. I just glanced in there. Here she was laying there, not a goddamn stitch on. Just laying there.

“You know the guy who bought the milk route off me. In about three months, he didn’t have no customers left. He did what I just would not do. He accommodated these women. His business just went to hell.”

While my father was resisting temptation and saving his milk money, his entire family moved up to Grand Coulee to plug into Roosevelt’s job-making machine. His brother Albert became a jackhammer foreman, a brother-in-law became a crane operator, and another brother-in-law was a concrete foreman. My grandfather Alfred, assisted by his younger children, opened a very profitable grocery store.

The dam rescued the Hardens from the Depression, allowed them to stick together, and even gave them savings accounts. After my father sold his milk route in 1939, when business was at its peak, he put $2,200 in the bank. His Grand Coulee savings, more money than he had ever seen in his life, paid for welding school in Seattle and gave him a high-wage skill. He also made friends at the dam who later helped him secure a welding foreman’s job at the shipyards in Portland during World War II. If not for his Grand Coulee contacts, my father never would have been put in charge of an all-woman welding crew in Portland. He would not have had a chance to meet Betty Thoe, a dark-haired, eighteen-year-old girl from North Dakota who was a member of my dad’s welding crew and who became my mother.

On a cloudless Saturday morning in May, my father and I drove the seventy-five miles from Moses Lake up to Grand Coulee Dam. We had made a bargain. He would tell me everything he could remember about the dam in the thirties, about B Street, about his milk route—and I would buy him lunch at the Wild Spot cafe. Like most father-son transactions, the deal favored me. But my father welcomed the excuse to look at the dam. He was a month shy of eighty-two years old and had not been up to Grand Coulee in years.

It had been abnormally hot across the Pacific Northwest in the previous week. Snow in the Cascades and Canadian Rockies was melting much faster than normal. The Columbia was rising rapidly. Behind Grand Coulee Dam, Lake Roosevelt was bumping up against its flood-control maximum. It being a weekend, with electricity consumption low across the region, the Bonneville Power Administration had no market for excess power. It could not, therefore, feed the swelling river into Coulee’s turbines. For the first time in two years—for one of the very few times since the generating capacity of the dam was tripled in the 1970s—the Columbia River was too big to be corralled or ingested. It had to be spilled. The dam had to become a concrete waterfall. At 5 A.M. that morning, the gates on the spillway opened.*

We had no idea any of this was going on until we drove down into the river canyon on the steep highway that comes in from the south. Before we could see the spillway, we heard the dull thunder of falling water. We hurried to the narrow road that runs across the top of the mile-wide dam. Leaving the car unlocked, we rushed to the railed sidewalk that looks down over the dam’s spillway. The river seemed to explode as it fell. The dam trembled beneath our feet. We had to shout to talk. At the base of the spillway, 350 feet below us, the Columbia seethed, boiling up a milky spray in the warm May wind, before scuffling downstream and turning a marbled green pocked with sinkholes. The din from the falling river and the vibration from the dam made my father smile. For him, it was like hearing a song from the thirties, a snatch of dance-hall music from B Street.

It triggered memories for me, too, but of a different kind. I had once worked at Grand Coulee. I got fired after less than four weeks.

When I was in college in the early 1970s, my father was again working at the dam. Grand Coulee was expanding, acquiring a new powerhouse, and my father—then in his early sixties—was a welder on the project. He used his contacts at the dam to get me a summer job as a union laborer. It paid the then-princely sum of five dollars an hour. My labor crew cleaned up bits of wire, half-eaten pickles, cigarette butts, gobs of spat-out chewing tobacco, and whatever else might be left behind by craftsmen who were higher up on the wage scale. Ironworkers, men who tie together the steel reinforcing bars that form the skeleton of a concrete dam, were not above blowing their noses and peeing in the places we laborers cleaned. This, of course, was the same job that my father had hated when he worked at the dam in the thirties.

I was nineteen at the time, between my freshman and sophomore years at Gonzaga University in nearby Spokane, and greatly impressed with myself. On the job at the dam, I made a point of telling the guys on my labor crew how unutterably boring our jobs were and how I could not wait to get back to school. Many of the laborers were middle-aged Indians with families. They kept their mouths shut and their eyes averted from me.

Federal inspectors nosed around after our work, sniffing out untidiness. They often spotted un-picked-up wire and other crimes. They complained to a superintendent who complained to some other boss who complained to an unhappy man named Tex, the foreman of our labor crew. Tex then yelled at me, the gabby, self-infatuated college boy. Tex (I never learned his last name) was not much of a talker. When he did speak, he had an almost incomprehensible West Texas twang. Meaning to say “wire,” he said something that sounded like “war.” Nearly everything else he called “shit.”

“Git off yer ass, pick up that war ’n shit,” he instructed me, after complaints about our crew’s cleaning efforts had trickled down the chain of command.

Our labor crew worked the swing shift, four to midnight, performing custodial duties near the spillway at Grand Coulee. The river, swollen in the summer of 1971 with heavy snowmelt from the Canadian Rockies, rioted over the dam twenty-four hours a day. The cascade had eight times the volume of Niagara Falls and fell twice as far. The base of the dam was a bedlam of white water and ferocious deep-throated noise. Tex would shout “war” in my face, but I barely heard him. Along with the racket, cold spray geysered up, slathering the construction site in a gauzy, slippery haze that was slashed at night by hundreds of spotlights.

Two men were killed the summer I worked at the dam. One was run over by an earthmover as he left the parking lot in a Volkswagen bug after his shift. Another died when someone knocked a bolt off a ledge. It fell a couple of hundred feet before punching a hole through his hardhat. The entire dam site—wrapped in the spray and yowl of the river—struck my sophomoric sensibility as a death trap. At weekly safety meetings I filled out lengthy reports on what I considered to be hazardous work practices on the part of our labor crew.

By my fourth week at the dam, Tex had had enough. He told me at the end of the shift not to come back. He mumbled something about how I spent too much time on my butt when big bosses were around. I slunk away from the river without an argument, driving home alone to Moses Lake after midnight. A stream of Gordon Lightfoot dirges played on a radio station out of Chicago, and I just barely managed not to cry. I was worried about what my father was going to say. His welding job at the dam paid for the Volvo I was driving, for the eight-hundred-dollar initiation fee that got me into the Laborer’s Union, for a big slice of my college education. My father had been shrewd enough to work much of his life for men like Tex without getting canned. He had gone to considerable trouble to line me up with the best-paying summer job a college kid could find in eastern Washington. And I had been too much of a smart aleck to keep it.

When I got home at 2 A.M., I left a note for my father on the kitchen table. He would be getting up in three hours to drive back up to work at Grand Coulee. The note said I was sorry for letting him down, which was true. What I did not say was that I was relieved to be away from that river.

Before he went off to work that morning, my father came into my bedroom and woke me up. He was not angry. He said it was not my fault, although he must have known it was. He said I was a good son, and he never again mentioned my firing.

As we stood together on top of the dam twenty-three years later, we did not say a word about any of this. Instead, I told my father that the noise, the vibration, and the height of the dam scared me. He said it did not scare him, that it had never scared him.

My father told me at lunch that he had felt a sense of loss when he left Grand Coulee in the late thirties. Living in the boomtown had been the wildest, most exciting adventure of his life. Unlike many of his friends, he had had the good sense not to blow his money on B Street. The Biggest Thing on Earth put money in his pocket and launched him on a career as a union craftsman—as a home-owning, car-buying, pension-earning family man.

I asked my father if he had ever doubted the wisdom of building the dam. He said no he had not. He did not seem to think my question made any sense.

In the environmental literature of the American West, one federal agency dwells alone in the innermost circle of hell. The late Wallace Stegner, the West’s most gifted and authoritative writer on land use, found something redeeming in all the other federal agencies that administer the open spaces beyond the Mississippi, where the federal government owns about half the land. Stegner praised, albeit with reservations, the stewardship of the National Park Service, the National Forest Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Bureau of Land Management, which oversees grazing land. Stegner believed these agencies had made “western space available to millions. They have been the strongest impediment to the careless ruin of what remains of the Public Domain.”

But the Bureau of Reclamation, Stegner wrote, “is something else. From the beginning, its aim has been not the preservation but the remaking—in effect the mining—of the West. . . . It discovered where power was, and allied itself with it: the growers and landowners, private and corporate, whose interests it served. . . .”

Stegner blamed the Bureau for, among other things, failing to protect the family farm, for encouraging westerners to use three times as much water per capita as people back East, for poisoning farmlands with salts from ill-designed irrigation systems, for concentrating power in the hands of a technocratic elite, and for building reservoirs whose constantly changing levels leave dirty bathtub rings in the most splendid canyons of the West.

In the demonic picture of the Bureau that has been painted by Stegner and a growing number of western historians, the foot soldiers of evil are civil engineers: the men (always men, white men) who designed dams and supervised their construction. These engineers have been derided as deracinated henchmen of a centralized state intent on bastardizing nature to make money for a well-heeled elite. The engineer’s job in the West, argues Donald Worster in Rivers of Empire, “is to tell us how the dominating is to be done. The contemporary engineer is the best exemplar of [the] power of expertise. Though not himself necessarily concerned with profit-making, he reinforces directly and indirectly the rule . . . of unending economic growth.”

Bureau engineers stand accused of transforming rivers into purely commercial instruments: acre-feet of water banked in reservoirs and kilowatt-hours to be traded or sold. “In that new language of the market calculation lies an assertion of ultimate power over nature—of a domination that is absolute, total, and free from all restraint,” Worster writes. “The behavior that follows making water into a commodity is aggressively manipulative beyond any previous historical experience.”

L. Vaughn Downs, eighty-eight years old and living with his wife, Margaret, in a retirement home when I made his acquaintance, did not look or sound like a manipulative agent of the devil.

The retired Bureau engineer had a big bald head, a flat prairie accent, and a firm handshake. He was the son of a Kansas hog farmer. He was courtly, sharp of mind, precise of speech, and hard of hearing. He had read some of the books that vilified the Bureau and its engineers. But they appeared not to have made him bitter. He dismissed the criticism as ill-informed speculation from non-engineers who did not have their numbers straight. The Stegners, the Worsters, and the rest of the environmental bunch had written nothing that tested his faith in the Bureau, nothing that made him doubt the rectitude of Grand Coulee Dam.

Downs devoted his entire professional life to the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of the dam and its irrigation system. He joined the Bureau in 1931, fresh from engineering school at the University of Kansas. For an aspiring builder of dams, his timing could not have been better. Within a year, Roosevelt was elected president and the Bureau was given a blank check to remake the rivers and deserts of the West.

Downs went to work in the Bureau’s design office in Denver where blueprints sat on drafting tables for what would become the world’s four largest dams—Hoover, Shasta, Bonneville, and Grand Coulee. The young engineer combined good timing with even better social contacts. He married into the Bureau’s hierarchy. In a passage from his memoirs that is characteristically short on sentiment but long on engineering detail, Downs explains how he fell in love in the Denver office:

“When the Bureau held an open house to display its new 5,000,000-pound capacity testing machine in the breaking of a mass concrete test cylinder 36 inches in diameter by 72 inches in height, many of the Bureau personnel and their friends and families were present. Such a test had never been performed before. There with my friends . . . was a young woman. We were introduced. She was Margaret Savage going to art school in Denver and residing with her Uncle Jack.”

Uncle Jack was John Lucian Savage, an internationally known Bureau engineer, a member of the Popular Mechanics’ Hall of Fame, and the chief designer of Grand Coulee Dam. With Uncle Jack’s blessing, Downs was transferred from a drafting table to a field position as an assistant engineer in quality control at Grand Coulee. He arrived in the Columbia Basin in May of 1934, and he never left. Margaret married him in 1935, and they moved into a tidy yellow house at the base of the dam site in Engineer’s Town, which the Bureau built exclusively for its engineers, senior administrators, and their families. The hardscrabble world of my father—cold-water shacks and B Street’s seedy diversions—was just up the hill. But as far as Downs was concerned, it might as well have been on the moon.

The men of the Bureau lived in a separate, subsidized world—physically apart from and socially superior to the workers and the private contractors. The rigid caste system at the dam site stunned newcomers from the East who had assumed that in a western boomtown they would find a classless society. Esther Rice, a schoolteacher from Manchester, New Hampshire, and a graduate of Vassar College, taught school in Grand Coulee in the late 1930s. Nothing surprised her more than the Brahmin status of Bureau men like Vaughn Downs.

“I thought it was fantastic that a government job would bestow such power,” Rice told me. “I had met powerful people back home . . . but these Bureau people were different. They exuded the feeling that they had the final power over everything in life. You had to be very careful around the Bureau men about what you said.”

When I learned that Downs was living in the Hearthstone Retirement Home in Moses Lake, I called him up and proposed the same deal that I had made with my father. I would buy him lunch in Grand Coulee in exchange for his allowing me to see the dam through his eyes. Like my father, he could not resist another look at the dam. After I picked him up on a Saturday morning at the retirement home, he wasted no time in showing me how a Bureau engineer of his generation, a man who came of age in a federal agency where smart young people fell in love at concrete-crushing parties, sees the West’s greatest river.

“There are three basic questions in building a dam,” Downs explained as we drove north to the dam. “Where? What of? What do you get when you are finished? To all of these questions, Grand Coulee provided excellent answers.”

I tried several times to turn the conversation to other questions. What did the Bureau do to Columbia River Indians? What did it do to the salmon in the river? What hijinks do you remember about B Street? Downs seemed uninterested, a bit irritated. He referred me to his memoirs. But The Mightiest of Them All says little about B Street and nothing about the effect of the dam on the Colville Indians, whose reservation borders it. As for salmon, the book argues—rather incredibly—that the dam’s blocking off of 1,400 miles of salmon spawning grounds on the upper Columbia “did not kill off the salmon resource in the river, but apparently enhanced it.”

So we talked about basic dam questions. Where? What of? What do you get? As Downs explained it, there could not have been a more perfect place to build the world’s largest dam.

“Nature provided everything but the cement,” Downs said.

First, there was the river canyon where the dam was secured to bedrock. Beneath a layer of loose rock and earth, engineers from the Bureau found, to their delight, that the Columbia was cradled in a U-shaped abutment of solid granite. There is, Downs said, no better rock to pour concrete on.

Then, of course, there was the river, incomparably useful for making electricity, and dependably fat in the hottest months when irrigators would want to bleed it for water. Downs was also pleased to point out the massive irrigation storage reservoir, otherwise known as the Grand Coulee, that nature had had the courtesy to dig right next to the dam site.

The Grand Coulee is the largest and most spectacular of all the scars gouged in the Pacific Northwest by the catastrophic floods that came at the end of the last ice age. Fifty miles long, between one mile and six miles wide, with sheer basalt walls nine hundred feet high, it astonished the first white men who saw it. Lieutenant T. W. Simons of the U.S. Cavalry said that “its perpendicular walls form[ed] a vista like some grand old ruined roofless hall.” An American fur trader, Alexander Ross, described the coulee as “thickly studded with ranges of columns, pillars, battlements, turrets, and steps above steps, in every variety of shade and colour. . . . Thunder and lightning are known to be more frequent here than in other parts; and a rumbling in the earth is sometimes heard. According to Indian tradition, it is the abode of evil spirits. . . . It is the wonder of Oregon.”

The coulee was cut about twelve thousand years ago after a massive sheet of ice, moving southeast out of what is now British Columbia, choked off the flow of the Columbia. The ice dam (located quite close to the spot where the Bureau chose to pour its concrete) backed up the river, creating a giant lake that soon spilled, with savage force, out of the river canyon. The flood washed south, reaming a trench for itself out of volcanic rock—the Grand Coulee.*

When the weather warmed up, the ice plug melted, the ice sheet retreated, and the Columbia returned to its original bed. The Grand Coulee, North America’s most splendid runoff ditch, was left high and dry and perched more than five hundred feet above the southeast bank of the undammed river.

It was still dry as a bone, with rattlesnakes, tumbleweeds, and Indian rumors about evil spirits, when Vaughn Downs took a bus to eastern Washington in 1934. He remembers thinking to himself, “My God Almighty, what a desolate country.” It took Downs and his Bureau colleagues nearly twenty years to do it, but they filled the big ditch with water. They installed twelve huge pumps behind the dam, which in the summertime can suck a billion gallons of water a day out of the Columbia and spit them up over the lip of the river canyon into the coulee. They named the lake that drowned the Grand Coulee after the late Frank A. Banks, the Bureau’s chief construction engineer at the dam.

Banks, the dominant personality in the building of the dam and a man who ranks at the top in Downs’s pantheon of great Bureau engineers, made no secret about what the Bureau was trying to do in the West. He preached “total use.” In a speech to utility executives in 1945, he said: “Our high level of living is chiefly a matter of the intelligent use of power and machinery. If we would have more, we must produce more. We must use more power.”

As Downs and I drove along the edge of the Grand Coulee, the engineer took pains to make me appreciate how remarkably suited the coulee is for its government-assigned duty of storing irrigation water. Downs explained that the basalt rock, out of which the Grand Coulee was cut by the long-ago flood, is virtually watertight. The coulee holds water, he said, almost as well as a glass mixing bowl. To prove just how tight the basalt was, he asked me to drive to the southern tip of the twenty-seven-mile-long reservoir.

I stopped my car, as instructed, on a dirt road about a mile south (and downhill) from the end of the reservoir. Downs directed my attention to two eighteen-inch culverts that passed beneath the dirt road. A scant trickle of water flowed in the culverts.

“That’s all the water that gets away from Banks Lake,” Downs said, quietly triumphant. “The total increase in water in the lower Coulee is on the order of half a cubic foot per second. Like I say, it’s tight rock.”

When we visited the dam itself, Downs continued to direct my attention to basic questions. He told me more about rock, a special kind of rock called aggregate: a round, river-polished, gravel-like stone that is a key ingredient in making concrete. To build the world’s largest concrete structure, the Bureau needed unlimited local access to high-quality aggregate.

Downs explained that nature provided a vast deposit of aggregate, conveniently located on the riverbank, right next to the dam site. It was so convenient that it did not have to be trucked to concrete mixers. The rock arrived by conveyor belt.

“This was really high-quality aggregate. There isn’t any better that we know of,” Downs said at lunch, allowing himself to use superlatives.

Again, I tried to steer the conversation. Why didn’t the Bureau build fish ladders at the dam, like at Bonneville Dam on the lower Columbia, which was built at roughly the same time? Did the height of Grand Coulee (350 feet) make fish passage an engineering impossibility?

“It was just money. If you build a dam, you could sure as hell build a fish ladder,” Downs said.*

I asked, again, about Indians. What kind of contact did the Bureau have with the nearby Colville tribe? Did Bureau engineers ever attend the Salmon Days festival that the tribe holds each summer and to which it invited everyone in the region? “I never went up to Salmon Days and I never knew anyone who did,” Downs said, adding that he had heard that the “sheriffs up there locked up the drunks around tree trunks with handcuffs.”

The engineer shifted back to familiar ground, back to rocks and basic questions. As Downs explained it, the construction of the dam was preordained: The aggregate for the concrete was pushed down from Canada by the prehistoric glacier that plugged the river that made the coulee that the Bureau made into the irrigation storage reservoir that hardly leaks. The Bureau, it seemed, was merely finishing up a job on which God had been an early subcontractor.

If God did want the dam built, He did not tell the Bureau, or at least He did not tell the Bureau first. The idea of building the dam originated in a small-town lawyer’s office in the Columbia Basin desert in the late spring of 1917. It came up as five young business and professional men from the fly-blown town of Ephrata, Washington, discussed the bleak prospects of raising crops and building a community with less than eight inches of rain a year.

One of them mentioned that he had taken a trip up to the Grand Coulee with a University of Washington geologist who told him how a glacier plugged up the Columbia and diverted the river. Billy Clapp, the young lawyer in whose office the men had gathered, was struck by an idea. If nature could do it with ice, Clapp asked, why couldn’t men do it with concrete?

“In their ignorance of the engineering features involved, those present conceded that it might be a good idea,” recalled W. Gale Matthews, who attended the meeting. “No one, however, had the courage to go out and say very much about the idea, fearing the kidding which would result.”

The idea languished for more than a year until Rufus Woods, a newspaper publisher from nearby Wenatchee, drove his Model T into Ephrata looking for advertisements and news. He got wind of the dam, interviewed Billy Clapp, and adopted the Grand Coulee scheme, first as a circulation gimmick for the Wenatchee World, then as a cure-all for the local economy, and finally as the defining cause of his life.

Woods, a failed lawyer and failed Yukon gold miner, devoted almost twenty years of breathless front-page coverage to the dam. “Such a power,” Woods wrote, in a typical eruption of boosterism and bombast, “would operate railroads, factories, mines, irrigation pumps, furnish[ing] heat and light in such measure that all in all it would be the most unique, the most interesting, and the most remarkable development. . . . in the age of industrial and scientific miracles.” The publisher sent special editions of his paper, which explained the miraculous national benefits of the dam, to every member of Congress. Eastern engineers and local politicians who were less than ecstatic about the dam were scorned in Woods’s newspaper. A World subscriber, after sixteen years of reading about the dam, complained in a letter that “when a person thinks and talks about the same subject continually, he is mentally unbalanced and headed for the insane asylum.”

What Woods wanted from the dam, however, was eminently sensible. It was what every small-town booster across the underpopulated West wanted: to get a rich outside benefactor to subsidize the transformation of his region into an agricultural-industrial hub, while preserving a profitable measure of local control. The trick, as Woods described, was “to get the government to do it” and “at the same time protect the interest of the locality.”

When his crusade was won—with the election of Roosevelt and the federal decision to build the dam—Woods learned the humiliating lesson that the Bureau of Reclamation taught local boosters in river basins across the West. Namely, federal funding with local control is an oxymoron. The Bureau runs what it builds. It and the Bonneville Power Administration took over Grand Coulee Dam. They owned its electricity. With the Army Corps of Engineers, they dictated the future of the Columbia River. Federal technocrats exercised power, and locals like Rufus Woods were reduced to exercising their lungs.

Most of Grand Coulee’s electricity was piped out of eastern Washington on federally built long-distance power lines to factories on the West Side of the Cascades or to the secret plutonium plant at Hanford. Wenatchee never became an industrial center. North-central Washington State remained a boondock. Woods never got over the loss of local control that was the price of winning the dam. The federal takeover was “just as wrong as it can be,” he wrote in a 1943 letter. “This whole section [of eastern Washington] has been treated as though it were a scrub.”

The resentment that Woods and his white middle-class business associates felt at the hands of Bureau engineers like Vaughn Downs was largely a matter of bruised pride and lost local business opportunity. It had nothing to do with doubts about damming the river, destroying salmon runs, or flooding land. The Columbia Basin Development League, of which Woods was president, was concerned above all else with squeezing dollars out of the Columbia. Its motto quoted Herbert Hoover: “Every drop of water that runs to the sea without yielding its full commercial return to the nation is an economic waste.”

Grand Coulee did generate a purer, less mercantile kind of resentment. On the far side of the dam, it festers on in the collective memory of a people who—before the arrival of the Biggest Thing on Earth—centered their existence on salmon.