Slackwater II

Slackwater II

WE SAILED WEST out of the desert, leaving Hanford and the Tri-Cities behind, nudging downstream through low fog that clung like cobwebs to the surface of the river. I emerged from my cabin at dawn to find the wind all but dead, and the air perfumed by shoreline sagebrush soaked with dew. A lone Canada goose, cruising low beside the barge, stamped the glassy river with a fleeting stereoscopic image of its long-necked self. On a small green island in the river, five chubby mule deer grazed on grass that apparently was tasty enough to justify a half-mile swim. Two cargo trains rumbled by in the near distance, also heading west—the Burlington Northern on the Washington State side, the Union Pacific on the Oregon side. It being September, leaves on scattered willow trees along the shore were beginning to yellow. Color fancied up the border between the deep blue river and the dead brown land.

Up in the wheelhouse of the tugboat Defiance, Steve McDowell, barge captain and my slackwater impresario, looked poorly. His complexion was pasty, his eyes red and baggy. He wore the same grimy command uniform, blue jeans and a black T-shirt, that he was wearing when I left him in the wheelhouse around midnight. He had been up most of the graveyard shift, standing at the helm of his tugboat until his tow cleared the narrows into which the Snake River funnels before spilling out into the Columbia.

Late summer is a skittish season for barging at the downstream end of the Snake. Spring and summer snowmelts have come and gone; fall rains have not yet begun. The barge channel shallows up by about three feet, reducing the margin for error in the rock-lined narrows. McDowell worked and worried until nearly four in the morning before he safely squired his hulking conglomeration of freight out into the wide, deep waters of the Columbia. He then turned the tow over to his pilot, Ernie Theriot, and went to bed. Theriot was instructed to stop in the Port of Pasco and shuffle barges. This meant two hours of yanking around on the riverbank, gunning engines, tying and untying cable. Barges of wheat and wood chips were dropped off; barges of frozen French-fried potatoes and partially tanned cowhides were taken on. The jolting shuffle rolled me around in my cabin bed. McDowell, too, had trouble executing his two-hour snooze. He was back in the wheelhouse promptly at six, chewing tobacco, slurping coffee, scratching his ample stomach, and squinting out at the dawn-smeared river.

When I came up the wheelhouse steps shortly after sunrise and caught sight of the skipper’s haggard face, I sensed a bad day coming. McDowell, however, proved far happier than his face. Indeed, he could not have been more delighted with the dawn, the river, and the world as he knew it. He politely asked how I had slept and recommended a restorative high-cholesterol breakfast of bacon, eggs, and toast with butter. I asked McDowell how it was that he looked so bad and felt so good.

The skipper replied that he would soon be free of the barge, free of the river, free of me. His fifteen-day stint on the Snake and Columbia ended this morning.

It was crew-change day.

“For fifteen days, I don’t even have to think about this job,” McDowell explained.

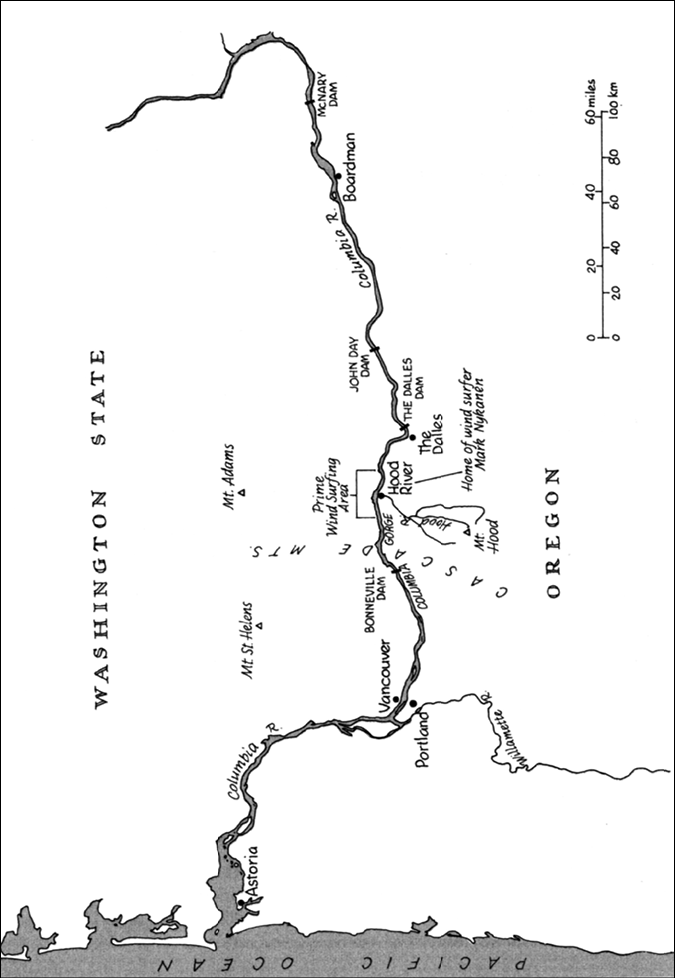

We had just cleared the locks in McNary Dam. The Snake River canyon country was far behind us, and the Columbia Gorge would not begin to rise in the west for another hundred miles. The rapids that used to torment this stretch of the river had been buried for decades under slackwater. We lumbered through a table-flat, intensely cultivated landscape that fed off the puddled-up river. All around us, sprinklers serviced orchards, vineyards, and fields of alfalfa. The flaccid Columbia was more than two and a half miles wide.

For migrating salmon, this seventy-six-mile-long reservoir that backs up behind John Day Dam is the deadliest stretch of the commute to the Pacific. (The last of the big federal dams on the mainstem of the Columbia, John Day was completed in 1971.) Young salmon often swim six days to traverse this part of the river, a reach that their pre-dam ancestors moved through in less than a day. To cut the commuter death rate, state and federal fish agencies and Indian tribes have proposed a number of schemes to speed up the river. The least ambitious of them would lower the level of the reservoir by about nine feet. That would marginally perk up the flow of the river—without halting barge traffic—and increase salmon travel time by up to 15 percent. The most ambitious scheme would lower the river fifty-eight feet, triple the velocity of the current, and whisk salmon through in about a day and a half. The latter scheme would require extensive relocation of irrigation pumps and intake pipes for municipal drinking water supplies. It also would halt barge traffic on the mid-Columbia. It would put men like McDowell out of work.

It being a splendid morning on crew-change day, I did not have the gall to ask the skipper about the possibility that his career might come to an end so fish could live. McDowell, however, needed no prodding. Sometime in the hours of his night’s navigation he had prepared a valedictory speech, a summing up of the difference between people who work for a living and people who fret about endangered salmon. In McDowell’s geography of the river, most of the former lived here on the dry side of the Cascades.

Salmon lovers—a pernicious sub-tribe of the yuppie infidel—lived over on the wet side. Beyond the mountains, as McDowell explained it, there was self-delusion, narcissism, and a basic misapprehension of the human experience.

“These Portland and Seattle people eating berries and twigs and watching foreign films believe they will live forever. They care more about the environment than about religion.

“People living over here on the East Side, particularly around Hanford, they know damn good and well that they are going to die. They take their religion real serious. They put these fish in perspective.

“We [barge operators] are the ones who keep the export markets alive in the Northwest. Every blow to our industry increases the price of our region’s exports. We are pricing ourselves out of the market. For the yuppies, nothing but a good dose of hunger will put their feet back on the ground.”

Whatever else might be said about McDowell’s little speech, it did have the virtue of good timing. By the end of the day, the barge would enter the Columbia Gorge, cut through the Cascades, and follow the river into a different version of the West.

It is almost impossible to overstate the differences between the two landscapes that are separated by the Cascade curtain yet roped together by the river. I first noticed it when I was nine years old and riding in the backseat of my parents’ car.

We were crossing the Cascades, going from Moses Lake to Seattle for the 1962 World’s Fair. The passage from brown to green, from sagebrush to trees made me squirm with excitement. No one could possibly have planted all those trees and nobody seemed to be watering them. In Moses Lake, if you did not water something, it died. The West Side, by contrast, was exuberantly alive. Besides trees and wild berries and rain forests choked with ferns, there were cities and freeways and parks full of flowers and spacious split-level houses on hills above lakes alive with sailboats. I remember being resentful when, after a week of the green, glittering city, we had to go back home to emptiness, irrigation ditches, and brown.

The division between the dry and wet sides of the Northwest has grown more pronounced with each passing year. The Columbia River was described in Joel Garreau’s The Nine Nations of North America as flowing between “essentially different civilizations.” The East Side, as Garreau explained it, was on the fringe of the Empty Quarter, which was “the most unpopulated, weakest-voiced, least-developed, who-cares? region of North America. . . .” The West Side, meanwhile, was the heart of Ecotopia, “which is developing the industries of the twenty-first century: lightweight alloys, computer chips, and ways to use them that are still in the future. Its natural markets and lessons about living are in Asia.”

The West Side was richer, more attuned to Far East trade, and more environmentally correct. Technology surpassed timber as the leading source of jobs in Oregon. Led by Boeing and Microsoft, Washington State was first in the United States in per capita income derived from exports. More than 80 percent of the state’s trade was with the Pacific Rim. Washingtonians earned twice as much from exports as Californians. Most of the high-tech growth was on the rainy side of Oregon and Washington, which accounted for 70 percent of regional population growth and where more than 80 percent of Northwest residents live. The West Side, as it prospered, spawned New West icons: billionaire Bill Gates, grunge rock, drive-in latte stands, microbreweries, and the only Major League Baseball team owned by a Japanese company. Nintendo owned the Mariners and nobody in Seattle thought it was un-American. Seattle recycled more garbage per capita than almost any American city. It and Portland ranked near the top in national surveys of books read per capita. Both cities were also leaders in per capita numbers of kayakers, hikers, windsurfers, sailors, bird-watchers, skiers, and mountain bikers. Thus occupied, the residents of these cities had significantly lower fertility rates than people on the East Side. British travel writer and transplanted Seattleite Jonathan Raban wrote that Seattle held a “curious niche” in urban history as a city “to which people had fled in order to be closer to nature.”

I collected personal ads in Seattle and the Tri-Cities newspapers for the better part of a year. They suggested that the river, as it runs west through the Cascades, leaves one planet for another.

In the Tri-Cities:

—Widowed WF, 42. Lonely and shy, enjoys movies, walking in the park, bingo, barbecues. Seeking WM, 40 to 50, for companionship.

—DWM, 50s, 5' 10", 190 lbs. Developing a ranch. Seeks sincere, pretty, s/dwf for lasting relationship.

In Seattle:

—The finer things in life. Very pretty, thin, happy, financially successful, athletic, 32, SWF, educated health professional seeks intelligent, happy, active, NS, ND or light, no TV, age 32–45, financially successful professional. With a busy schedule I meet few men that I am interested in. I love bicycling, gardening, interior decorating, investing, reading recent Ayn Rand & Michael Talbot, thinking and intelligent conversation. A beautiful city home and country retreat provide a tranquil background for a peaceful, introspective, spiritual life. I am financially successful & strongly emphasize that I seek the same. Photo. Letter only.

—Happy Birthday to Me. A true Cancer, I love water, home life & emotionality. Kayaker, herbalist, cook, hiker, yogi, world-traveler, jazz drummer, sweat lodger, wolf-lover. 6', height-weight proportional. Back from a “roots” trip to Ukraine, I’m ready. I’ve been waiting for you, so let’s fall in love. But 1st, tell me about yourself. Maybe a photo.

On the East Side, in small towns like Moses Lake or Grand Coulee or Colville, you cannot sit in a coffee shop for more than half an hour without hearing someone in a John Deere cap complain about West Siders with too much money and too little sense telling working people how to live. In Seattle or Portland, you can sit in an espresso bar for weeks on end without hearing a single reference to the East Side, excepting the odd complaint about poison leaking out of Hanford.

East Side communities made a habit in the 1990s of passing anti-gay-rights ordinances that West Side judges and politicians made a habit of declaring unconstitutional. The out-of-doors, on the East Side, is not a holiday destination, but a workplace. And jingoism is nothing to apologize for. On an evening’s walk down Main Street in the East Side logging and cattle town of Colville, Washington, I saw a sign in a clothing store that said: “We only sell clothes made for hard-working Americans, by hard-working Americans.” Nearby was a taxidermy shop where the display window was crowded with stuffed bears, mountain goats, bobcats, and a buffalo.

Gun shows attract huge, enthusiastic crowds in small towns across the East Side. I attended a show in the Grant County Fair Grounds in Moses Lake where the most crowded booth offered Israeli-made black-matte-finished, field-stock Galil .308-caliber assault rifles for $1,750. Large crowds also pored over the publications booth at the gun show, which offered how-to pamphlets including “Construct the Ultimate Hobby Weapon: Homemade Grenade Launchers” and “Heavy Firepower: Turning Junk into Arsenal Weaponry.” The most prominently displayed poster at the show was of Adolf Hitler. Under his scowling face was a slogan: “When I come back, no more Mr. Nice Guy.”

In Portland’s fashionable Nob Hill neighborhood a few weeks later, I stumbled upon the West Side antipode to the gun show. A young mother and her two well-dressed children were on their knees on the sidewalk, petting a Dalmatian who was out for an evening’s walk on the rhinestone-studded leash of its owner. Before the mother stood and loaded her children into her minivan, she told the dog’s owner: “Thank you for letting us enjoy your dog.”

The end of the river shift for McDowell and his three-man crew turned out to be Boardman, Oregon, a desert town that smelled strongly, from out on the river, of French fries and cow manure. Barge pilots and deckhands get on and off the river when their shifts start and end, no matter where the barge may be on the 350-mile run between Lewiston and Portland.

McDowell’s wife had driven to Boardman for the shift change, as had the wives of other men on the outgoing and incoming crews. A group of about fifteen waited on the dock. Behind them, a thick column of steam rose in the windless morning from a potato processing plant. After we tied up, incoming and outgoing bargers, along with their wives, girlfriends, and small children, drank coffee, ate doughnuts, and gossiped for about an hour. The shift-change picnic was one of the few social gatherings that barging offers the men and their families, whose homes range from the Oregon coast to northern Idaho. Before leaving for his home in the Columbia Gorge, McDowell graciously took a minute to introduce me to the incoming skipper, Pat Harding.

“He is even more of a redneck than I am,” McDowell said, waving goodbye.

By river barging standards, Harding was a clean-liver. He conspicuously lacked the wheelhouse paunch that connotes command on the river. Nor was he divorced, like so many men who work on barges. Nor did he smoke cigarettes or chew tobacco. He was born in Walla Walla, Washington, where he lived fifteen days a month with his wife and young sons. While he was home he slept fitfully, missing the rhythms of the river, finding that his internal clock could not abandon a barge’s schedule of six hours on, six hours off. Forty-two years old, short and muscular, with thinning hair and a well-tended mustache, he had twenty years on the river and fourteen years in the wheelhouse as a skipper. As we steamed toward Portland, Harding seemed less redneck than worrier. Problems on the river that annoyed McDowell seemed to make Harding physically ill.

Before chugging back out into the river, we had to pick up more freight. At Boardman, there were barges of fresh Walla Walla sweet onions, cubed alfalfa and frozen peas from around my hometown, and empty garbage containers. Tidewater Barge Lines, the principal barging company on the Columbia-Snake System and my host on the river, has an intermountain garbage arrangement. Tidewater hauls compacted garbage upriver from the far side of the Cascades—from the fast-growing city of Vancouver, Washington, and surrounding Clark County—and dumps it in sparsely populated Morrow County, Oregon, in a landfill about ten miles from Boardman.

This west-to-east migration of garbage—by barge, rail, and truck—had become a growth industry in Oregon and Washington, as the swelling population of Ecotopia (despite strict recycling laws) produced more and more waste and the Empty Quarter remained relatively empty. In nearby Arlington, another small desert town on the Oregon side of the river, trucks hauled trash to the largest landfill in the Pacific Northwest. Eastern Oregon coveted urban garbage for the same reasons that the Tri-Cities coveted nuclear waste: lots of empty land and the locals had convinced themselves it was both safe and good for the economy. Judge Louis Carlson, chairman of the Morrow County board of commissioners, told me that Tidewater paid his county about two hundred thousand dollars to accept the garbage. For a county of just eight thousand people, Carlson said, two hundred thousand “adds up.”

After barges with onions and garbage containers were lashed to the tow and we nudged back out into the river, I climbed down out of the wheelhouse and went for a walk on our two-hundred-yard-long vessel. As the late morning turned warm, the cargo was beginning to ripen. Side by side, just in front of the tugboat Defiance (which pushed six barges, tied two-abreast), were warring odors, one seductive, the other sickening.

To the left, the invigorating tang of freshly picked sweet onions. The pride of Walla Walla, the onions are the Northwest’s highly competitive answer to gourmet sweet onions grown in Vidalia, Georgia. To the right, the dried-blood, flu-vomit stench of a barge carrying leaky containers of partially tanned cowhide. The hides, bound for a baseball-glove factory in South Korea, wept a salty solution that slickened and corroded the barge’s steel deck. As the sun grew hotter on the becalmed river, the smell of the hides overwhelmed the onions. The hides became the fragrance that perfumed my passage through the Columbia Gorge.

Fleeing the smell, I climbed back up to the wheelhouse. It was just before noon. On Tidewater barges, six-hour shifts always change on a fixed schedule. The captain takes the best hours, from six in the morning until noon, from six in the evening to midnight. Harding had been at the helm for only an hour or so, but he was about to give control of the barge over to his pilot. Before doing so, he gave me a simple, quick, and painless (for him) prescription for saving salmon and stopping all this nonsense about removing dams or drawing down the river.

“The first thing you do,” Harding said, “is you shoot all the seals.”

For bargers, nothing symbolized the decline and fall of common sense on the river as neatly as seals. The population of seals and sea lions in the Pacific Northwest has risen sharply since the federal government decided that it had to act to save marine mammals from extinction. For decades, Northwest fishermen had been shooting seals, sea lions, and otters to keep them out of their nets and stop them from creaming off the salmon catch. The Marine Mammal Protection Act made harming these creatures a federal crime. It worked far better than intended.

When the law was adopted in 1972 the population of harbor seals in Washington began growing by 6 to 10 percent a year. By 1999, it had increased to more than thirty thousand. Federal fishery officials said that by 2011 the numbers in Washington and Oregon were at the carrying capacity of both states. California sea lions, much larger mammals that can weigh up to nine hundred pounds and eat forty-five pounds of fish a day, also thrived under the law. These bewhiskered, double-chinned mammals began taking extended vacations in the Pacific Northwest, feasting on threatened salmon in the Columbia River and other waterways.

A few of the sea lions had the bad luck to become celebrities. A group of them, collectively known as “Herschel,” began taking their holidays at the Ballard Locks in Seattle, where they decimated a wild run of Lake Washington steelhead. Fish and game authorities bombarded the sea lions with rubber-tipped arrows, rubber bullets, bad odors, firecrackers, and amplified calls from killer whales. Still they stayed on, eating salmon and getting fat. In desperation, fish agencies captured the sea lions and trucked them to California. They swam back and continued to eat more steelhead in front of television cameras.

Harding told me that each spring on the lower Columbia he saw more and more sea lions (as many as four thousand have been counted in the river), even as the numbers of returning adult salmon continued to decline and schemes to remove dams or draw down the Columbia (and ruin his life) gathered steam.

“Just what the hell is going on?” Harding asked, echoing the outrage of barge owners, utilities executives, and irrigators who see salmon-scarfing sea lions as an easily understood and cost-free distraction from the dams and reservoirs that kill 80 percent of the salmon in the Columbia Basin.

Conservationists have been forced by the sea lion imbroglio to concede that mistakes have been made in ecosystem management. At the urging of Washington State lawmakers, Congress acted in 1994 to amend the Marine Mammal Act so that intransigent sea lions, after 180 days of scientific review, could be subject to “lethal removal.” But even the congresswoman who wrote the sea-lion-killing amendment made a point of telling the House of Representatives that dams and forestry practices—not marine mammals—were the primary culprits for the decline of salmon. Representative Jolene Unsoeld, whose western Washington district borders the river, said, “we cannot and should not claim that seals and sea lions are what’s causing the decline of our salmon runs in the Northwest.”*

Having pronounced a death sentence on marine mammals, Harding handed over control of the barge to his pilot and went to lunch. For the next six hours, I stayed on in the wheelhouse with the pilot, Michael Warren, thirty-seven years old, fifteen years on the river, five years in the wheelhouse. We steered clear of any discussion of seals, salmon, or drawdowns. We watched the river as the Columbia Gorge began to rise on both sides.

The irrigated plains gave way to hills of gray rabbit grass streaked with black seams of basalt. The gorge slowly gathered altitude as we moved west through the only sea-level passage in the mountains between California and Canada. A thousand feet above the river, scarred gorge walls showed off the high-water mark of the Ice Age floods that reamed out the gorge. On this stretch of the Columbia, at a distance of more than a hundred miles from the crest of the Cascades, it used to be routine in good weather to see the towering snow-capped volcanic peaks of the Cascades. The most prominent, Mount Hood (elevation 11,235 feet), used to float in the southwest horizon like a child’s dream of an ice-cream cone. Lewis and Clark saw Mount Hood from a distance of 150 miles. The peak, in the last decade of the twentieth century, is more often than not shrouded in a bluish haze of smog that rolls east through the gorge from Portland and the heavily populated Willamette Valley. There was not a cloud in the sky, but we could not see Mount Hood.

I asked Warren, who grew up in Heppner, Oregon, a town in the eastern outback of the Columbia Basin, what brought him to the river.

“A paycheck,” he said, “and I wanted to get out of the desert.”

With the salary he earned on the river, the pilot could afford to live in Seaside, a fashionable resort town on the Oregon coast. Barging on the Columbia, Warren said, allowed him to return regularly to the sagebrush country he grew up in and still loves. More important, he said, it paid him enough money to live someplace less dull.

Speaking of dull, Warren said, piloting a 614-foot-long, 14,000-ton tow in slackwater is among the dullest jobs imaginable—except when something is about to go wrong.

“We have hours upon hours of boredom, and seconds of sheer panic in which you can cause millions of dollars of damage, and maybe even kill some people. If you hit something with 14,000 tons, it gives. You have to treat everything—docks, bridges, other tows—as if it was made from eggshells.”

Two days after Warren told me about treating bridges like eggshells, a much smaller river barge in Alabama struck a railroad bridge. An Amtrak train jumped the rails on the damaged trestle and tumbled into Bayou Creek, killing more than forty people.

The unboring part of Warren’s life, he said, occurred when he was off the river, chasing women. The twice-divorced, now-single pilot treated me to an extended episode of “As the Barge Turns,” the true-life (but possibly wildly exaggerated) sexual antics of river men who have fifteen days a month off the barge to fool around. Throughout the long afternoon, as we followed the sun west into the mouth of the gorge, squinted into a white ribbon of glare, and endured the odd whiff of rank cowhide from the barge below, I learned everything there was to know about a rich, married, well-dressed, and large-breasted woman named Rhonda. He met her on the boardwalk at Seaside. She took him on the road in her red BMW. She seduced him in the garden of the Columbia Gorge Hotel. She paid his way to Vegas. She was a terrific human being, if a bit unstable.

“For health reasons, I had to stop seeing Rhonda,” Warren said. “Her husband gave me a call.”

After nearly four hours of the Rhonda story, it was shift-change time. I followed Warren to the galley for pork chops with gravy and fresh corn on the cob that one of the incoming deckhands had brought from his farm. Then it was back up to the wheelhouse, to spend the evening with the skipper.

Harding was listening, as he always does on evening shift in the wheelhouse, to conservative talk-radio. Callers complained about tax-and-spend, anti-family feminism, and environmental overkill. The callers inspired Harding to tell me how the Columbia River was being ruined by liberals.

As an example, the skipper pointed to house lights that were beginning to twinkle on each side of the darkening gorge.

“The new lights in the gorge you cannot believe. There are more every week, as these yuppies build their perfect homes with perfect views of the river. With all these new lights, sometimes you cannot tell where the navigation aids are. You can’t find the channel. It is more stress for me. I don’t need more stress.”

The lights reminded Harding that sailboats in the lower river around Portland were multiplying out of control and “they don’t seem to think anymore that they have to get out of the barge channel when we come through.” Then, he grumbled, there were fishermen who will not get out of the way, even when he honks his foghorn for minutes at a time. The list of stress-producing problems on the river expanded to fill the long evening: “ignorant oil pollution laws,” periodic drawdowns of parts of the Snake River that “are supposed to save salmon but make it more dangerous for us to operate,” and Indians who fish at night without running lights.

As we sailed into the night, the highways and railroad tracks that line both sides of the gorge bristled with light. A tangle of headlight white and taillight red reflected off the river. The growl of big trucks and the clickety-clack of trains carried well on the water, coming in through the open windows of the wheelhouse to mix with talk-radio rants and Harding’s litany of river complaints. As we inched into the locks in John Day Dam, a huge bird, probably a great blue heron, bolted from its perch on the side of the dam and nearly crashed into the windows of the wheelhouse.

“That is stress I do not need,” Harding said.

Beyond John Day Dam, we sailed beneath the two most aberrant structures on the entire length of the Columbia. Both were built by a man named Sam Hill, a North Carolinian who married one of the seven daughters of James J. Hill, the railroad tycoon who built the Burlington Northern tracks on the Washington side of the river. High above those tracks on a treeless promontory, Sam Hill built a mansion for his wife, Mary, the tycoon’s daughter. She, however, categorically refused to come near Maryhill Castle. So Hill turned it into a museum, and in 1926 he lured a not-very-important European aristocrat, Queen Marie of Romania, out to Columbia Gorge to dedicate the castle. The queen left behind a few pictures of herself and some gilt furniture, which remain on display. Greatly impressed with things European, Sam Hill went on to build a concrete and cut-stone full-size replica of the ancient Druid temple of Stonehenge. It looms above the gorge as a memorial to veterans of World War I who were born in Klickitat County, Washington.

Down on the water we approached what used to be the diciest reach of the Columbia, the part that Captain William Clark described in 1805 as an “agitated gut swelling, boiling & whorling in every direction.” Before slackwater, the river was cinched into a narrow, eight-mile-long basalt canyon known as the Dalles.* It squeezed the Columbia from a width of more than half a mile to just 715 feet. The stone girdle provoked violent protest from the river, spitting white water, howling incessantly. At its upriver entrance, the Dalles canyon began with a twenty-two-foot drop called Celilo Falls.

Celilo was the most productive Indian fishing ground in the Northwest. All the adult salmon heading back to spawn on the upper Columbia, the Snake, and their tributaries had to jump the falls, where Indians took them with spear, gaff, net, and J-shaped baskets. The mid-1950s flooding of Celilo behind the Dalles Dam, like the flooding of Kettle Falls behind Grand Coulee, is remembered by local tribes as an act of cultural genocide. Native American poet Elizabeth Woody described what happened after the dam went in.

There is Celilo,

dispossessed, the village of neglect . . .

Fishermen and their wives know of.

Men who fish son after father.

There are drownings in the Dalles,

hanging in jails and off-reservation-suicide towns.

The Indians who continue to fish in this stretch of the river use gill nets, stringing them out in the lakes above and below the dams. Nets are constant irritants to barge pilots. Harding dreaded hitting them and provoking tribal complaints to Tidewater Barge Lines that could get him in trouble.

“You see that!” Harding yelped.

We were about twenty miles upstream of the Dalles Dam. It was around eleven and I was going down the stairs of the wheelhouse, heading for bed, when the skipper saw something alarming. He screamed for me to come back up. Out on the black river, captured in Harding’s wheelhouse spotlight, a small motorboat skittered across the Columbia in front of the barge. It had no lights.

“That’s some Indian tending his nets in violation of the law. He is supposed to have running lights. Now what am I supposed to do about that? If I hit him, it is my fault. You know what that is? That is more stress for me.”

I stayed on in the wheelhouse for almost an hour, grunting sympathetically as Harding told me about how Indians made him anxious.

Finally, I escaped to my cabin. The night was restful. The tow, other than passing through the locks at the Dalles Dam, did not stop. There was none of the torturous bumping—the all-night barge shuffle—that had ruined my previous attempts at sleep on the river.

Beyond the Dalles, the barge chugged past Hood River, Oregon, where, had it been daylight, thousands of windsurfers would have been gamboling on the river—stressing Harding out.

“You certainly don’t intend to stress out the barge pilots, but you get very focused on yourself. You are turning the board at high speed in big waves, going back and forth across the river, and all of a sudden you look up and there is this thing in the river the size of a football field. Everybody who has ever windsurfed on that river has had close calls. Eventually somebody is going to die out there.”

So predicted Mark Nykanen, a Hood River windsurfer and just the sort of tall, dark, handsome, smart, articulate, affluent, environmentally aware, left-leaning, all-organic New West recreator who made barge skippers shake their heads in disgust.

A couple of weeks before my barge trip I had found Nykanen on a mountaintop not far from Hood River, where he lived in a soaring log house made exclusively of windfall pine. Wearing a T-shirt and running shorts, he invited me to ask him questions as he worked out in his second-floor bedroom, which afforded a sweeping view of nearby Mount Hood and Mount Adams. Lifting dumbbells and stretching a latex exercise band, he was strengthening the rotator cuff in his left shoulder, which he had torn while windsurfing. (He also had broken, while windsurfing, three bones in his foot and two toes.)

“Windsurfing, as it is done here on the river, is a very high performance sport,” he said.

Injuries did not keep Nykanen from boarding two or three times a week. He subscribed to a telephone service that reported wind speeds and directions at assorted windsurfing sites along the Columbia Gorge. Nykanen did not put on his black-and-blue neoprene wetsuit and head out to the river unless the wind was blowing at least thirty miles an hour, a velocity that creates large swells on the river. The swells are the display platform upon which expert windsurfers jump and execute high-speed turns called jibes.

“I was a gifted athlete growing up.” Nykanen told me, curling a dumbbell with his left arm, as strands of sweat ran down his long, lean face. “When I started windsurfing here in 1987, I devoted myself maniacally to the sport. I went out on the river every day for seven months.”

For a while, Nykanen sought out sixty-mile-an-hour winds that whip the surface of the river into an ethereal but treacherous spume that windsurfers call “liquid smoke.”

“That was sheer survival. I did it to prove I could do it. It was a kind of macho thing. It is something that I do not seek out any more.”

When not on the river, Nykanen recreated in the Columbia Gorge by mountain biking, hiking, all-terrain skiing, acting in local plays, and dabbling in the Hood River real-estate market, the value of which had soared, primarily because of windsurfing maniacs such as himself. Nykanen bought his first house in Hood River for $55,000 in 1985, the early days of the explosion in property values in the Columbia Gorge. When he sold that house four years later, he nearly tripled his investment and bought his ten-acre mountaintop spread. Nykanen explained that his house was on land zoned for forest use and that no other homes could be built on his mountaintop. “The gates are now closed,” he said.

Nykanen came to the gorge from Chicago, where he had won four Emmys in seven years as an investigative reporter for NBC News. He saved enough money from network television to subsidize his windsurfing obsession and to try to launch a new career as a novelist. After six years in the gorge, in addition to high-performance recreating, he had written three unpublished novels (one autobiographical, one historical, and one thriller).

“I haven’t watched TV since I left NBC. I quit because I fell in love with windsurfing, and national television news had become a complete joke. Local TV news is a kind of dementia. Also, I did not want to work for a bomb manufacturer [General Electric, an owner of NBC],” Nykanen told me, as he continued to exercise his left shoulder.

A vegetarian, Nykanen drank only organically grown coffee and poured rice milk in his morning bran. He subscribed to Mother Jones, Yoga Journal, and the University of California Wellness Letter. His main source of news was a Pacifica radio station out of Portland. He lived with his girlfriend, Cindy Taylor, also a vegetarian, who worked in the Dalles as a therapist for emotionally disturbed children. Nykanen worried frequently about the quality of the water in the river on which he sails.

“Undoubtedly, the river has been compromised. I have no faith that the government has protected the river from Hanford. Then you have the pesticides and herbicides from the orchards. You hear people grumbling, but they should be screaming.”

Nykanen would be happy to pay significantly more for electricity if that would help save endangered Columbia River salmon.

“We are already paying an environment tax that is self-imposed when we pay 20 percent extra for organic foods. So, sure, I would be willing to pay more for utilities to preserve the river and its fish,” said Nykanen, who heated his house with a large high-efficiency wood stove.

Before driving up to Nykanen’s house, I asked around in Hood River, trying to find out what locals think of well-heeled windsurfers. In a decade, they transformed a depressed logging community of 4,800 people into an international resort where half the housing was owned by people who lived out of state. Store clerks and waiters resented being unable to afford to buy or pay rent in town, where a small apartment went for two thousand dollars a month during the windsurf season. A non-windsurfing auto mechanic who was born in Hood River told me that he kept a windsurf board on top of his car year-round because it allowed him to drink and drive without fear of harassment from local cops who did not want to annoy big-spending, out-of-town “board-heads.” Sheriff’s Deputy Greg Sandercock, who fished injured and hypothermic windsurfers out of the river, acknowledged that one need not look far to find spiteful locals in Hood River.

“Some of these windsurfers you can compare to spoiled rich kids. They certainly are not criminals, but they are used to doing anything they want. You hear them in the stores or the streets saying that this town would dry up and blow away if they weren’t here.”

Up on his mountaintop, I asked Nykanen about local anger. What about the indignation of irrigators, barge operators, and utility executives who claimed that imports like him were going to shut down the Columbia so they could jibe around in wetsuits and speculate in real estate?

“When I first moved here, I remember people driving past me and flipping me off. Obviously, I looked different; I wasn’t local. But that has begun to fade away. There’s been a decrease in antagonism. People sold out for good money and left, or they stayed and prospered from the windsurfing business.

“As for the claim that urban yuppies are taking control of the river, that is complete bullshit. I don’t doubt that the perception is there, but it is the perception that industry wants the public to accept. Extractive industry in the Northwest engages very effectively in spin control.

“What people around here don’t realize is that this region was dying from a kind of economic leukemia long before the windsurfers showed up. There has been a degeneration of vital fluids, caused by the timber industry, pulp mills, Hanford, and hydroelectric dams. I consider windsurfing to be low impact. We kill no salmon. We dump no heavy metals. We spill no oil.”

Speaking of barge pilots in particular, Nykanen apologized for the torment that he and tens of thousands of other windsurfers put them through.

“I totally empathize with them. We don’t mean to be such a pain in the ass around the barges. But we are busy sailing, and we just don’t see them.”*

I woke up on a river cloaked in green. The barren East Side, with its rock-pierced sand, endless sagebrush, and thousand shades of brown, was gone. During the night we had sailed out of the rain-shadow desert and into the wettest slice of the American West. Douglas fir and western hemlock ruled the high shoulders of the gorge, and down by the Columbia there was an uproar of Pacific willow, red alder, black cottonwood, creek dogwood, and stinging nettle. Although the sun shone in a cloudless sky, the air was cool and humid. It softened the morning and deepened the encircling green.

This would be my last day on the barge. We were nearing the locks in Bonneville Dam, the final dam on the Columbia. Portland was a little more than forty-five miles away. There, the tow would be pulled apart, its cargo loaded on ships for the Far East. The empty garbage containers would be refilled with compacted trash and sent back to the Empty Quarter. The tugboat Defiance, too, was scheduled for a quick turnaround. It had burial detail. It would push a deactivated nuclear reactor from a U.S. Navy submarine upriver for deposit at Hanford.

Just upriver from Bonneville, the tow hugged the Washington side of the river, following the shipping channel. A few hundred feet off the starboard side, a half-dozen small fishing boats (crowded with families of non-Indians wielding fishing rods and large mugs of coffee) were anchored near the mouth of a small mountain river that spilled into the Columbia. Decked out in rain gear despite the sunshine, they seemed in a foul temper. They did not return my wave. Perhaps it was because the three-foot wake from the tow nearly capsized their boats, forcing them to drop their fishing rods and coffee mugs and hang on for dear life.

I joined the deckhands in the galley for what proved to be a bracingly impolitic breakfast. Both Jim Richardson, forty-two years old and seven years on the river, and Jeff Blank, thirty-four years old and fourteen years on the river, were in expansive moods. Part of the reason was concrete. Until just a few months ago, at this point on the trip to Portland, the deckhands would have been out on the barges, untying cables and breaking the tow down into smaller pieces that would fit through the narrow locks of the fifty-six-year-old dam. Only two barges and a tug could fit through at one go. For nearly two decades, Bonneville had been the biggest bottleneck on the Columbia-Snake System, forcing deckhands to work outside for hours, unmaking and remaking the tow in a stretch of river often made miserable by rain and wind and cold. New bigger locks at the dam, built at a cost of $340 million, allowed our tow to pass whole through the dam. Deckhands could sit in the galley and eat. Also perking up the deckhands was the good fortune of having snuck around Hood River in the dead of night, thereby eluding the windsurfing hordes.

Since the mid-1980s, deckhands have had to stand out on the bow for daylight passage through the gorge, keeping an eye out for downed windsurfers. A fully loaded barge cannot stop in less than a quarter mile of river, so deckhands can only scream into their walkie-talkies if a windsurfer spills in front of the tow. Mostly, deckhands stand out there in the wind and curse the carelessness of people playing chicken with fourteen thousand tons of freight.

I told the deckhands about the windsurfer who was sorry for being such a pain in the ass. I explained that windsurfers get so self-absorbed they cannot see the barges. The deckhands rolled their eyes; it was not news to them that windsurfers were self-absorbed hazards to navigation.

“I fish those board-heads out of the river all the time. One had his mast snap in the wind. He had hypothermia by the time we got to him and was out of his mind. He was taking off his gloves and throwing them into the river. He couldn’t sit on top of his board,” said Richardson, who, when he was not on the river, raised sweet corn in Wamic, Oregon, an East Side town south of the Columbia. “We saved his life and he didn’t even say thank you.”*

Disgust with windsurfers seemed to remind Richardson of how annoyed he was by endangered salmon and the damage they are doing to his career. He made me some pancakes and launched into the single most politically incorrect argument that I heard about endangered fish on the Columbia.

“The biggest mistake they [the federal government] made was putting fish ladders in at Bonneville Dam. If they hadn’t done that, all this business about salmon would be over.”

With no fish ladders at Bonneville, the entire Columbia River watershed above the dam would have been permanently sealed to migrating adult salmon. All the salmon and steelhead runs above the dam would have been wiped out. All plans for salmon restoration would be moot. Federal judges, Indian chiefs, fish biologists would all stop poking their noses into barge business.

The deckhand’s argument was explosive stuff. Given the environmental orthodoxy of the Pacific Northwest, it was hate speech, akin to decrying the end of slavery or denying the Holocaust. No politician, no utility executive, no producer of aluminum, no owner of a barge line that uses public waterways would dare repeat what the deckhand said, at least in public. Certainly, it would be convenient for river users and large industrial electricity consumers such as aluminum companies if salmon disappeared, but saying so—especially on the West Side of the mountains, in Ecotopia—would be a public-relations disaster.

It was not always apostasy to speak openly of destroying all the salmon. Grand Coulee Dam, as we have seen, blocked the upper Columbia River Basin. Hells Canyon Dam, which was completed in 1967, blocked the upper Snake River Basin. It is hardly surprising, then, that had the Army Corps of Engineers had its way back in the early days of the New Deal, Bonneville Dam would have done the same for virtually the entire river, accomplishing precisely what the deckhand suggested.

The chief of the Corps, responding in the early 1930s to fishermen’s protests about the proposed dam, reportedly said, “We do not intend to play nursemaid to the fish!”

The Corps has denied that any such thing was said. An official Corps history of Bonneville fuzzes over the question of whether or not the agency wanted to save salmon. However, Milo Bell, a hydraulic engineer who worked for the Corps at Bonneville in the 1930s and who invented its fish ladders, told me that the Corps’ original design for the dam would not have allowed salmon upstream. Bell, a professor emeritus at the University of Washington, said that without public pressure the Corps would not have spent the money necessary to make fish passage work and salmon runs would have been destroyed. Corps engineers, Bell recalled, made “a lot of snide comments about salmon.”

Before we cleared the locks at Bonneville, I left the deckhands in the galley and climbed up to the wheelhouse, where I overheard the lockkeeper warn Captain Harding on the radio that there were “big doings” downriver. Jodie Foster and Mel Gibson were just downstream, making a movie.

“Watch out,” the lockkeeper said, “you don’t want to run over a movie star.”

Below Bonneville, for the first time since I boarded the barge back in Idaho, the Columbia was not contained between plugs of concrete. Dam makers had found nothing of compelling interest on the river from here to the sea. The steep drop of the Columbia was exhausted. The river went tidal, became flabby, and took on the lazy personality of the Mississippi. Just beyond Bonneville, however, there was one bit of moderately swift water left. We skated over Garrison Rapids (which has no white water and which I would not have recognized as a rapids without Harding telling me it was a rapids) at about ten miles an hour, which is two miles an hour faster than normal for a fully loaded tow, and considerably faster than Harding prefers to travel when hoping that he does not run over a movie star.

“We’re scooting,” Harding complained, pulling the handle on the tow’s warning horn. A stiff breeze was at our backs. The Oregon side of the river was lined with the yellow tents of fishermen. Scores of them were out in small boats, casting for Columbia River sturgeon, bottom fish that can grow up to six feet long and weigh eight hundred pounds. If the fishermen are stupid enough to get in front of him, Harding said, he cannot stop.

A possible celebrity sighting occurred shortly before 9 A.M. We had come abreast of Beacon Rock, a gargantuan black boulder on the north bank of the river that is second in size only to Gibraltar. (The 848-foot-high rock is the central neck of a former volcano.) At the base of Beacon Rock, we saw a freshly painted Old West paddle-wheel riverboat lying at anchor. Then, scampering upstream from Portland, a motorboat approached on the port side of the tow. Sitting in the stern of the boat, out in the bright morning sun, her blond hair blowing in the breeze, her eyes intent on a fluttering script held tightly in both hands, we could conceivably have seen Academy Award winner Jodie Foster on the way to filming one of her most forgettable performances in the movie Maverick. Harding, whose binoculars were better than mine, was sure it was she.

Just downriver we came alongside Multnomah Falls, a 620-foot-high rope of white water that wows drivers on Interstate 84 as it sprays out of the Oregon side of the gorge toward the river. Clear across the river on the Washington side, three tiny black-tailed deer drank from the edge of the Columbia. They kept raising their noses between sips, sniffing in the direction of the passing tow, perhaps wondering why the usual smell of diesel exhaust was spiced with onions and cowhide.

We saw our first windsurfer of the day at Rooster Rock State Park, a not very good and not very popular place to sail. He gave the barge an extremely wide berth. Harding said there was a nude beach at Rooster Rock, but binoculars revealed nothing. A luxury cruise ship, the Sea Lion, slipped past us, heading upriver. It was packed with mostly white-haired people. On the open back deck, several of them rode stationary bicycles with their noses buried in paperbacks. As Mount Hood lorded over us from the Oregon side, the gorge began to peter out, mountains giving way to high rolling hills.

Handing me his binoculars, Harding pointed to a distant ridge on the Washington side. I saw a three-story mansion with a lawn sweeping down toward the river. There were barns, a gazebo, and twelve llamas grazing on the lawn. It was the home of the man who owned the barge I was riding on and whose Tidewater Barge Lines hauled four out of every five tons of freight on the Columbia-Snake River System. Ray Hickey was a hero to the men on the barges. He started out on the river in 1951 as a ten-dollar-a-day deckhand. By the mid-1990s, he was the sole owner of a company—with holdings in shipping, solid waste removal, docks, and environmental cleanup services—with total assets worth well over $140 million.

“That’s where Mr. Hickey lives,” Harding said respectfully. “As you can see, he is a wealthy man, but he earned every penny of it. He likes llamas.”

Mr. Hickey.

A short, heavyset, intense man with thick glasses and stubby fingers, he granted me an audience at his company’s headquarters in Vancouver, Washington, a city across the river from Portland. His public-relations adviser sat in on our forty-minute conversation. Hickey told me four times that he was an environmentalist.

He was an environmentalist who did not buy the generally accepted consensus among fish biologists, environmental groups, fish and wildlife agencies, and federal courts that hydroelectric dams and slackwater reservoirs are primarily responsible for killing salmon in the Columbia and Snake. He was an environmentalist who dominated a shipping industry that is dependent on a river that, as historian Donald Worster puts it, was killed by dams and reborn as money.

“I don’t believe they have established what it is that makes the fish disappear,” he said. “I think you have to figure out what the problem is before you make a solution. You know the seals at the mouth of the Columbia are eating the fish.”

Hickey, who was sixty-five years old when we talked, acknowledged that in his lifetime there has been a wholesale change in the economy and culture of the Pacific Northwest, with the emergence of companies like Microsoft and Nike, which he said “don’t need the river and want to protect the appearance of the place.

“The political atmosphere now is that you have to give the impression that you are protecting the environment. It gets you votes here if you are the big savior.”

But Hickey said he had to disagree with these cosmetic notions about what is worthwhile on the river and in the West. He said that farmers “are the backbone of the country. They are the ones who have the integrity to go out and make something work.”

I asked Hickey, whose company’s profits were built on grain transport, how he would describe the river. I mentioned that a prominent lobbyist for the hydropower industry called the Columbia a “damn fine machine.”

Hickey closed his eyes for a moment, smiled broadly, and said he found the description “perfect.”

“It is a machine,” he said with satisfaction, nodding his head vigorously.

Then Hickey caught the eye of his public-relations adviser, who was sending nervous nonverbal signals to the effect that the word “machine” might be a bit too mechanical.

“Maybe ‘machine’ is the wrong word,” Hickey added quickly, “It is more a system. . . .”

After several false starts on organic, non-reductionist descriptions of the river, the barge magnate gave up on describing the river and began speaking of his affection for the Columbia, his lifelong stewardship of it, and how he always has believed that an American businessman should never “forget where you came from.” He again said that he regards himself as an environmentalist.

I asked Hickey about the generous federal subsidy that pads his bottom line. Barging companies pay only about a quarter of the operating costs for locks on the Columbia and Snake. They paid none of the construction costs. At the mention of the word “subsidy,” Hickey—the self-made millionaire—looked away from me in annoyance.

“The statement that we are subsidized . . . ,” he said, shaking his head. “This sort of thing is said by people who do a lot of talking without knowing what they are talking about.”

Hickey then conceded that barge companies do receive a substantial subsidy.

“Barge lines don’t pay their share,” he admitted. “Who does?”

Hickey sold Tidewater Barge Lines a few years after we spoke. He became a philanthropist, giving away more than $20 million to hospitals, land trusts, and the creation of public trails where people can go to walk along the lower Columbia. He died in 2002.

As the Defiance slipped into the suburbs of Portland/Vancouver, the only metropolis the Columbia passes through on its run from the Canadian Rockies to the sea, the river was surrounded by handsome new houses. The gentle slope of land up away from the river became a manicured setting for five-bedroom, high-ceilinged, three-car-garaged suburban manses. A few of the finest had private, rock-walled bays that gave suburban sailors access to the river. Through picture windows that faced the river, I saw men and women in their dens, towels around their shoulders, faces flushed from exertion, working out on Nordic Tracks and Stairmasters, watching our barge plod by.

Beyond the suburbs, we entered the port of Portland, a busy freight yard where the Willamette flows into the Columbia, where goods from the interior are hustled off barges and loaded into ocean-going cargo ships. In heavy port traffic, a tug called the Betty Lou appeared and began picking our tow to pieces. The Betty Lou made off with our peas and onions, then with the cowhides, then with grain barges, and finally the empty garbage containers.

Just before I, too, was off-loaded, Mike Warren, the pilot who had regaled me with tales of Rhonda, offered an epitaph for men who work on barges.

“There is a reason why they keep us bargers locked up on the boats for fifteen days at a time,” Warren said. “It’s so society only has to deal with half of us at any one time.”

Portland/Vancouver is where the levers are shifted on the river that Ray Hickey would not for public-relations reasons say is a machine. The levers, quite literally, are shifted in a basement in Vancouver. There, in the Dittmer Control Center, a cavernous computer-filled room that looks like Mission Control in Houston and that was built to withstand nuclear attack, power dispatchers from the Bonneville Power Administration send out signals every six seconds that raise and lower gates on dams, grooming slackwater to system needs.

The power dispatchers in the bombproof Vancouver basement, however, merely execute orders. Those orders are written by a contentious gaggle of river managers—electricity marketers, fish biologists, federal judges, members of Congress, Native American leaders, utility lobbyists, barge companies, irrigators, aluminum companies, and federal bureaucrats. The managers fight with each other endlessly, angling to shape the Columbia according to wildly contradictory notions of what a river should be. They play a kind of multi-dimensional chess game with rules that bend to economic muscle and biological research, environmental law and political fashion.

The fact that fourteen thousand tons of freight had just managed to float downriver to Portland meant that champions of slackwater, for all their hand-wringing about dam removal and salmon and environmentalists, were still winning the game.

In Portland, where many of the players have their offices, I decided to poke around, trying to figure who was winning, who was losing, and why.