The influence of French archaeologists spreads beyond the borders of France, throughout Europe and beyond. The first part of the chapter considers the archaeologists, not all of them French, whose archaeological work in France has made a significant contribution to our knowledge of the past. The second part of the chapter discusses innovations of French archaeology, the case studies being the naming of type sites for phases of the Paleolithic period in Western Europe and beyond from sites in France, the development of underwater archaeology, the use of aerial photography in archaeology, and the application of archaeological science in France.

Early Archaeologists

As discussed in chapter 1, interest in France’s past began in the early sixteenth century, when certain learned individuals assembled collections of Gallo-Roman antiquities. However, it was not until the work of Bernard de Montfaucon (1655–1741) that objects were considered as historic documents in the same way as texts.

Bernard de Montfaucon, perhaps best known as the individual who first used the term paléographie to describe the study of ancient handwriting, also was interested in the material remains found in France. In 1719, he published an account of the megalithic tomb found at Cocherel (Eure), discussed in chapter 1, in which he deduced that it must have been from the “stone age” because of the absence of metal. Montfaucon was drawing on the work De rerum natura written in the first century BC by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius. Lucretius proposed the concept of a “three-age system,” which demonstrated the cultural development of humankind by their use of available materials, namely, stone, followed by copper, then iron. In addition, in 1734 Montfaucon showed his interest in ancient indigenous artifacts through his presentation Anciennes Armes des Gaulois in a communication to the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres.

Jacques Boucher de Perthes (1788–1868) became a key figure in the knowledge of the antiquity of humans. In 1825, Boucher de Perthes became director of the customs office at Abbeville (Somme). As discussed in chapter 1, it was not until the 1840s that his application of the method of stratigraphy, borrowed from geology, to prehistory indicated the presence of humans in the area much earlier in time than previously believed.

In 1863, Boucher de Perthes was awarded the Légion d’Honneur by the emperor Napoleon III and was invited by the emperor to deposit the outstanding pieces from his archaeological collection in the museum founded in 1867 in Saint-Germain-en-Laye (Yvelines), today the Musée d’Archéologie nationale. The same year, these objects were exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Prehistorians

Among the many outstanding figures who pioneered the discovery of the Paleolithic period in France were Edouard Lartet, Emile Cartailhac, Denis Peyrony, and, the most renowned, Henri Breuil.

Edouard Lartet (1801–1871) initially was a lawyer, but he developed an interest in fossils from 1833, when he was shown a mastodon tooth. A few years later he discovered the first of a series of fossilized animal remains at his family’s property at Sansan (Gers) and subsequently published reports on his discoveries. Lartet joined in the scholarly debate on the age of early humans and their coexistence with extinct animals such as mammoths. Accordingly, in 1860 he began archaeological exploration of La Grotte du Ker de Massat (Ariège) and L’Abri d’Aurignac (Haute-Garonne), whose significant finds are discussed later in this chapter. Lartet’s excavations in the Dordogne in 1863 and 1864 were crucial in determining the age of human antiquity. The excavations were funded by the English banker and businessman Henry Christy (1810–1865), whose name perhaps is best known for providing the idea of the “Turkish towel,” the type widely used today, which was based on samples he brought home from his Eastern Mediterranean travels in 1849 and 1850. The type was popularized when Christy demonstrated a sample of “Turkish toweling” to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London.

In 1852, Christy largely withdrew from business. He already had an interest in social issues such as the rights of indigenous people and traveled widely in Europe, North Africa, and North and Central America, most notably in Mexico. Christy also wished to contribute to the current debate on human evolution, and in 1860 he visited the Somme Valley, where Jacques Boucher de Perthes had proved the association of humans and long-extinct animals. Lartet’s work in the Dordogne, funded by Christy, revealed evidence of human occupation that was more recent, and of a different type, than that previously found in the gravels of the Somme. In particular, Lartet’s excavation of l’Abri de la Madeleine, discussed further in chapter 2 and later in this chapter, is considered to provide definite evidence of human antiquity, as well as providing the basis for the subdivision of the late Ice Age into discrete periods. In 1864, Lartet and Christy published in the Revue archéologique what may be the first general article on Paleolithic art titled “Sur les figures d’animaux gravées ou sculptées et autres produits d’art et d’industrie imputables aux temps primordiaux de la période humaine” (On the engraved or sculpted animal figures and other pieces of art and artifacts ascribed to the primordial times of the human period). Lartet and Christy worked together on many sites in the Vézère Valley (Dordogne), including the Abri Lartet in the Gorge d’Enfer, L’Abri de Laugerie-Haute, and L’Abri de Laugerie-Basse, all in Les Eyzies; L’Abri de la Madeleine in Tursac; Le Moustier in Peyzac-le-Moustier; and Le Pech-de-l’Azé I in Carsac-Aillac. In Paris, Lartet, collaborating with Emile Cartailhac and Gabriel de Mortillet, discussed later in this chapter, was responsible for the prehistoric displays at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867. In 1868, Lartet was appointed professor of palaeontology at the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. His son, Louis, was also a paleontologist and geologist, and he excavated the site of l’Abri Cro-Magnon, discussed in chapter 2.

Like Lartet, Emile Cartailhac (1845–1921) trained as a lawyer but showed no interest in pursuing this career and devoted his life to the study of the prehistory of France and the Iberian Peninsula. Cartailhac was introduced to prehistory by his uncle, the naturalist Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau, and in 1863 excavated many dolmen tombs in the Causse de Larzac, a plateau in the south of the elevated region known as the Massif Central in central France. Cartailhac always was aware of the need to disseminate knowledge through museums and gave finds from his early excavations to museums in Toulouse and London. Furthermore, between 1882 and 1884 Cartailhac ran a free course in archaeology at the Faculty of Sciences at the University of Toulouse. From 1888 until his death in 1921, Cartailhac was professor of prehistoric archaeology at the Faculté des Lettres at the University of Toulouse.

Denis Peyrony (1869–1954) is another archaeologist who made a significant contribution to our knowledge of French prehistory, excavating at a range of important sites in the Dordogne département, such as La Ferrassie, Laugerie-Haute, le Moustier, and la Madeleine. In particular, the authenticity of Paleolithic cave art was established by Peyrony’s discoveries in 1901 at a further two caves close to Les Eyzies (Dordogne): namely, la Grotte de Font-de-Gaume and Les Combarelles I, the latter with Henri Breuil and Louis Capitan. In addition, in 1913 Peyrony founded the Musée des Eyzies, now the Musée national de préhistoire, at the ruined Château des Eyzies at Les Eyzies (Dordogne). In 1940, toward the end of his career, Peyrony, along with Jean Bouyssonie, André Cheynier, and Henri Breuil, recognized the importance of the paintings that had been discovered in the Grotte de Lascaux, discussed in chapter 2.

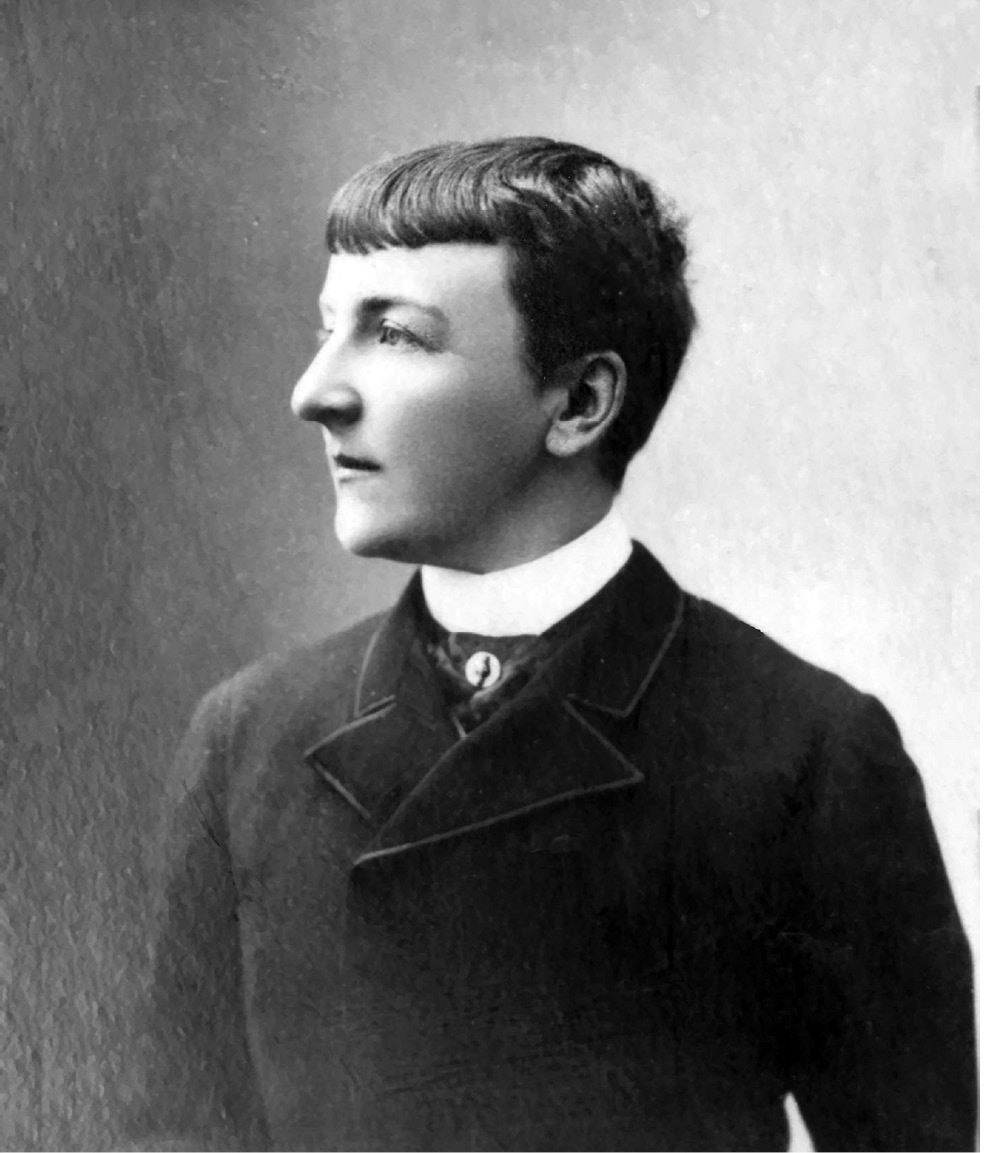

Henri Edouard Prosper Breuil (1877–1961) is considered the leading authority on Paleolithic art of his generation (figure 4.1). Breuil often is known by the title “Abbé” as he had trained as a priest, although he also had a strong interest in natural science, and one of his teachers at the seminary where he trained encouraged this interest. Indeed, Breuil was allowed to concentrate on the study of prehistory and undertook few religious duties. In summer 1897, Breuil and Jean Bouyssonie visited several important archaeological sites and made the acquaintance of many of France’s most eminent prehistorians, including Edouard Piette and Emile Cartailhac. As he had a talent for drawing animals, Piette and Cartailhac enlisted his help with the illustration of Paleolithic portable and cave art. Breuil discovered many decorated caves and galleries himself, and his work is important as his drawings are sometimes the only record of images that no longer exist. At the start of his career, Breuil undertook a few small-scale excavations in Le Mas d’Azil cave (Ariège) and the rock shelter Abri Dufaure (Landes). However, his later career was wider in scope and concentrated on other aspects of prehistoric archaeology, also working on the megalithic art of France. Outside France, he turned his attention to the Iberian Peninsula and in the 1940s began a project copying rock art in southern Africa. Although now superceded, Breuil’s view, based on ethnographical analogies, was that the main function of Paleolithic images was primarily as hunting magic. In addition, he considered the images in caves as single images arranged in groups.

Figure 4.1. Henri Breuil. Paul G. Bahn

André Leroi-Gourhan (1911–1986) generally is considered to be the most influential figure in the study of Paleolithic cave art and settlements in the 1960s and 1970s. After his studies, Leroi-Gourhan worked in various museums initially at the Musée d’ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. Between 1940 and 1943, Leroi-Gourhan was a curator at the Musée Guimet and subsequently at the CNRS (Centre national de la recherche scientifique). From 1944, Leroi-Gourhan was a lecturer at the University of Lyon, until his appointment in 1956 as chair of ethnology at the Sorbonne University in Paris, where he specialized in prehistoric art. During this time, he additionally served as deputy director of the Musée de l’Homme, part of the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. In 1969, Leroi-Gourhan was elected to the Collège de France, a long-established higher education and research establishment in Paris.

Leroi-Gourhan’s view was that students should be encouraged to undertake archaeological fieldwork. He conducted field schools at the Grotte des Furtins, in the commune of Berzé-la-Ville (Saône-et-Loire) between 1945 and 1948, and from 1946 at the complex of nine caves that form les Grottes d’Arcy-sur-Cure (Yonne), including the Grotte du Renne, discussed in chapter 2. At the field school at Arcy-sur-Cure, Leroi-Gourhan taught archaeological methods that were very different from those that had gone before. He laid great emphasis on meticulous excavation, paying particular attention to the different floor levels.

In 1964, a team from the CNRS, led by Leroi-Gourhan, began work at the open-air site of Pincevent in the commune of la Grande-Paroisse (Seine-et-Marne), a project which is still ongoing. The site was found accidentally, during commercial quarrying of sand. Leroi-Gourhan could use his then pioneering technique of horizontal excavation on a large-scale Paleolithic site, encouraging students to adopt these techniques. Leroi-Gourhan also pioneered the use of new archaeological techniques, including recording floors by making latex moulds. The Pincevent site had fifteen separate levels of occupation from the Late Magdalenian period, around 10,000 BC; and excavation revealed more than one hundred living areas, likely to have been covered with tents, and twenty large hearths. The animal remains, almost entirely reindeer bones, indicate that the site was occupied from early summer to early winter. It is considered that Leroi-Gourhan’s article “L’habitation magdalénienne no. 1 de Pincevent,” which was published in 1966 in the journal Gallia préhistoire, revolutionized the discipline of Paleolithic settlement archaeology.

Leroi-Gourhan’s research in Paleolithic art highlighted what he perceived as a dualism of male and female. Accordingly, he interpreted the horses and bison, whose images dominated the decoration of caves, as male and female, respectively. In addition, he believed that nonfigurative motifs should be interpreted as either male (phallus) or female (vulva). Furthermore, unlike Henri Breuil, whose view was that cave decorations were assemblages of individual images, Leroi-Gourhan believed that the decoration of caves were homogenous compositions that had been planned in their entirety and set out in a preconceived format. He studied the animal depictions in each cave, noting their location and associations with other animals, observing that 60 percent of all of the animals were horse or bison, in general depicted on the central areas of the caves. Other species, such as ibex, mammoth, and deer, were in more peripheral locations. Some species—rhinoceros, large cats, and bears—were rarely drawn, with any examples being shown deep in the caves. Accordingly, Leroi-Gourhan thought this model was a blueprint for cave paintings of animals. It is now believed that this theory is rather too general and that the pattern of depiction in each cave is different. Nevertheless, it is still recognized that the animal figures are placed on the cave walls in a deliberate manner.

In addition, Leroi-Gourhan devised a chronological sequence of four different successive styles of cave art, a theory now considered to be flawed. The approach of trying to identify groups of images that are similar stylistically and technically, and thus the work of a single artist or group, was rejected by Leroi-Gourhan. His belief was that Ice Age art remained essentially unchanged for twenty thousand years, a view that is now challenged. Since Leroi-Gourhan’s death, the consensus is that the decoration of caves is an accumulation of different compositions through time.

Discoveries of the earliest humans in France began in the 1960s at La Caune de l’Arago, also known as la Grotte de Tautavel (Pyrénées-Orientales), discussed further in chapter 2. Excavations began at the site in 1964 by a team of archaeologists led by Henry de Lumley (b. 1934), who, with his wife Marie-Antoinette de Lumley, also undertook excavations at two other French sites that have produced early evidence of humans, Terra Amata and la Grotte du Lazaret. Previously, from 1957 to 1968, he had excavated la Grotte de la Baume Bonne at Quinson (Alpes-de-Haute-Provence), a site with evidence of occupation from around four hundred thousand years ago. Henry de Lumley was also instrumental in the creation of Le Musée de Préhistoire des Gorges du Verdon at Quinson to house archaeological finds from the many sites in the area. The museum has a second site on the bank of the river Verdon, the “Village préhistorique de Quinson,” discussed further in chapter 1.

Jean-Paul Demoule (born 1947) is noted for his research on the Neolithic and the Iron Age in Europe, together with the history of archaeology and its social role. In addition he is prominent in the field of preventive archaeology, being instrumental in the development of French law in this area. Demoule served as president of Inrap (Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives) between 2001 and 2008 and is emeritus professor of protohistory at the Sorbonne university in Paris. Along with other archaeologists, he conducted excavations within the framework of the Programme de sauvetage regional de la Vallée de l’Aisne (Aisne and Pas-de-Calais), which took place between 1971 and 1992. Demoule was also involved in projects outside France, most notably in Bulgaria and northern Greece.

Iron Age and Gallo-Roman Archaeologists

Henri Rolland (1886–1970) is a leading figure in the archaeology of the Iron Age in France. Rolland’s interest in archaeology began with numismatics, a field in which he published discoveries from Nîmes (Gard), the oppidum of Entremont and the Gallo-Roman site of Glanum (both Bouches-du-Rhône). In addition, Rolland directed a number of excavations, a significant discovery being the oppidum at Saint-Blaise (Bouches-du-Rhône), which he excavated from 1935 at his own expense. From 1928 until 1933, Rolland worked on a sanctuary to the south of Glanum, taking charge of the site from 1942 until 1969. From 1945, Rolland ran what then was the only field school specializing in classical archaeology. In addition, he was appointed director of the Circonscription archéologique for Provence-Nord from 1956 to 1964. On the death of Fernand Benoit in 1969, Rolland became vice president for France of l’Institut international d’études ligures (International Institute of Ligurian Studies). Along with Benoit, Rolland was one of the first scholars to recognize the presence of Etruscan bucchero ware in southern France and to associate this with commercial links between the Etruscans and southern France.

Rolland also was prominent in finding a suitable setting for finds from excavations from the Glanum site at the late fifteenth-century mansion known as the Hôtel de Sade in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (Bouches-du-Rhône). The building was acquired and classified as a historic monument by the French state in 1929 at the behest of Jules Formigé (1879–1960), architect of historic monuments, and Pierre de Brun (1874–1941), who founded the Musée des Alpilles in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, both of whom had excavated at Glanum since 1921. From 1954, Henri Rolland was instrumental in ensuring that the Hôtel de Sade became the archaeological repository of excavation finds from the Glanum site, whose collection opened to the public in 1968.

Another major figure in the Gallo-Roman archaeology of southern France was Fernand Benoit (1892–1969). In 1922, Benoit had attended the Ecole française in Rome; on his return to France, he became an archivist in Arles (Bouches-du-Rhône) and later a curator, then director, of the Arles archaeological museum. At this time Benoit conducted excavations in the Arles area, including cemeteries at Trinquetaille and Alyscamps, as well as the water mill complex at Barbegal, discussed in chapter 3. In 1943 Benoit had been appointed director of historic antiquities of Provence and Corsica, and since 1946 had been director of the Musée Borély in Marseille (Bouches-du-Rhône). Archaeological work conducted by Benoit in the area around Marseille included the Gallo-Roman site of Cemenelenum in Cimiez, a suburb of Nice (Alpes-Maritimes); the crypt at Saint-Victor in Marseille; and the Vieux-Port of Marseille, the latter leading to his interest in shipwrecks, which he considered to be as important as land sites. However, as discussed in chapter 5, Benoit’s inability to dive led to the misinterpretation of the Roman shipwreck discovered at the rock of Grand Congloué, south of Marseille. Benoit was also a pioneer in working with archaeologists from other European countries, an unusual practice in the early twentieth century. With the Italian archaeologist Nino Lambroglio, Benoit founded “l’Institut international d’études ligures” and worked with other Italian and Spanish archaeologists.

French Archaeologists outside France

Other French archaeologists have made significant contributions to archaeology outside France.

One such individual was Charles Ernest Beulé, who had studied at the prestigious Ecole normale supérieure in Paris and the Ecole française d’Athènes, where he excavated on the Acropolis. His best-known discovery is the gate that bears his name, the Beulé Gate, which was built in the late third century AD to protect the sanctuary on the Acropolis, which was discovered during Beulé’s excavations in this area in 1852 and 1853. In 1859 he undertook excavations at Carthage at his own expense and was the first to reach the archaeological layer that revealed evidence of the destruction of the city in 146 BC. In addition, a Roman building at Carthage consisting of a series of vaulted rooms, known as “les Absides de Beulé,” is named after Beulé, While still holding the post of professor of archaeology at the Bibliothèque impériale in Paris, Beulé became a politician, was elected to the Assemblée Nationale in 1871, and served as minister of the interior in the Broglie government of 1873.

The vast majority of early French archaeologists were men, reflecting the social conventions of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An exception was Jane Dieulafoy (figure 4.2), considered to be the first female French field archaeologist, noted for her work in Persia and Morocco. She was born Jane Magre in Toulouse in 1851, and, showing early academic promise, was sent to Paris to be educated. In 1870 she married Marcel Dieulafoy, who shared her interest in art and archaeology. The extraordinary nature of Jane Dieulafoy’s life is reflected by her decision to accompany her husband when he served in the Army of the Loire in 1870; she dressed in male uniform and joined her husband at the front. In 1874, Marcel Dieulafoy became architect of historic monuments under Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, architect to the emperor Napoleon III. It is believed that his discussions with Viollet-le-Duc on the origins of Western architecture inspired the Dieulafoys to travel during the 1870s to Egypt, where the French scholar Auguste Mariette was conducting excavations; Morocco; and several European countries. In the 1880s the Dieulafoys traveled to Persia (modern-day Iran), visiting several cities, and obtained permission to excavate the remains of the ancient city of Susa in 1885 and 1886, the first French excavations on the site, which followed the work by the British archaeologist William Kennett Loftus in 1851. Among the discoveries Jane and Marcel Dieulafoy made were friezes of glazed bricks showing archers and lions from the palace of the Achaemenid King Darius I, who reigned between 522 and 486 BC. Four hundred crates of archaeological finds that had been excavated by the Dieulafoys in 1885 and 1886 were sent to Paris, where they were received at the Musée du Louvre by Léon Heuzey, who had been appointed as the Louvre’s first curator of the department of Oriental antiquities. On her return to France in 1886, Jane decided to continue to wear male dress, and photographs taken of her at this time made her famous. In the same year, she was honored by the French government with the award of Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur.

Figure 4.2. Jane Dieulafoy. Alamy

Jane Dieulafoy published an account of her work in Susa in the review Le Tour du Monde, as well as writing fiction, including Parysatis, whose action takes place in Susa, set to music by Camille Saint-Saëns in 1902. She was one of those who initiated the literary prize known as the Prix de la Vie Heureuse, first awarded in 1904, which became the Prix Femina, still in existence today.

From the 1880s, the Dieulafoys ran a “salon,” where men and women could engage in intellectual conversation, at their home on the rue Chardin in the Passy district of Paris. This became one of the most fashionable events in Paris, attended by scholars, poets, artists, and musicians, most of whom were members of l’Institut de France, discussed in chapter 1.

At the same time, the Dieulafoys visited Spain and Portugal, making twenty-three trips between 1888 and 1914. During World War I, Jane accompanied her husband to Morocco, where she directed the excavation of the Hassan Mosque at Rabat. Jane Dieulafoy died in Toulouse in 1916 following an illness contracted in Morocco. She is justly famous, as it was extremely unusual for a French woman to be a field archaeologist in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Although the Dieulafoys did not return to what then was known as Persia (modern-day Iran), excavations there were dominated by French archaeologists from the late nineteenth century onward. The main site was Susa, where excavations had resumed in 1897, conducted by Jacques de Morgan. However, in general, the focus tended to be on the nature of finds rather than their context. A more methodical approach to excavation in Persia was adopted by Roman Ghirshman (1895–1979), who was born in Kharkov in Ukraine and arrived in Paris in 1923. Ghirshman not only excavated at Begram, an Indo-Greek and Kushan city in Afghanistan, but also in Persia, known as Iran from 1935, and was unusual in conducting archaeological work outside Susa, for so long the focus of French excavations. Most notably, his work at Tepe Sialk in Kashan established the first chronology of Iranian prehistory. In 1946, Ghirshman was appointed director of the Mission Archéologique en Iran, and archaeological work recommenced at Susa, where, under Ghirshman’s direction, entire architectural complexes were being discovered for the first time.

Bohumil Soudský (1922–1976) was an influential figure in Neolithic archaeology. Although born in what is now the Czech Republic, Soudský studied at the Sorbonne University in Paris between 1946 and 1948, and from 1971 until his death in 1976 he returned to Paris to lecture in European protohistory at the Sorbonnne. Soudský’s excavation at the large Neolithic site of Bylany in the Czech Republic in the 1950s and 1960s led him to propose the idea of “cyclical agriculture,” which developed from the earlier hypothesis of “primary Neolithic shifting agriculture.” Soudský suggested that the development of pottery styles at Bylany was not a continuous process, which may have been caused by periodic abandonment of the site. Soudsk´y believed he had located other sites in the immediate area around Bylany, where pottery finds corresponded to gaps in the record at the main site. Accordingly, he proposed that the inhabitants of Bylany moved from one settlement to another on a regular basis as part of their agricultural system, to allow vegetation and the fertility of the soil to regenerate, with each cycle lasting on average sixty years. Soudský’s view was very influential at the time, although his hypothesis has been overtaken by more recent ideas.

Although Jean Guilaine (born 1936) has been involved in Neolithic and Iron Age archaeological projects in France, he is also noted for his excavations at the Neolithic site of Shillourokambos on Cyprus. The site achieved popular renown in 2004, with the discovery of the complete skeleton of a cat which accompanied a human burial dating between 7500 BC and 7000 BC. The deceased was aged around thirty at death, and was buried with offerings that included stone tools and ochre pigment. As no local feline species had been found, it was suggested that the remains represented the oldest known evidence for the domestication of cats. Jean Guilaine has had a distinguished academic and research career, serving as director of studies at the CNRS (Centre national de la recherche scientifique) and Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), as well as being an honorary professor of the Collège de France. He founded, with Daniel Fabre, the body now known as the Centre d’anthropologie de Toulouse. Guilaine is perhaps best known for the introduction of “agrarian archaeology,” using both environmental and archaeological data.

Not all archaeological work in France has been conducted by French archaeologists. For example, the English archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler undertook a survey of oppida in the regions of western Normandy and Brittany during the winter of 1936–1937. In 1938 he undertook excavations at several sites, most notably the oppidum popularly known as Le Camp d’Artus (Arthur’s Camp), close to the commune of Huelgoat (Finistère).

The Chronology of the Paleolithic Period

The valuable contribution of French archaeology to the study of Paleolithic stone tools is recognized by the large number of type sites for phases of the Paleolithic period in Western Europe and beyond. The names, derived from sites in France, first were used by Gabriel de Mortillet (1821–1898).

Previously, Edouard Lartet had also suggested a chronology for phases of the Paleolithic period. Lartet adopted the geological principles of stratigraphy to his study of l’Abri d’Aurignac, establishing a relationship between the type of animal and the geological layer in which its remains was found. At l’Abri d’Aurignac, Lartet distinguished four periods, defined by animal remains— namely, cave bear, mammoth and rhinoceros, reindeer, and aurochs or bison, with cave bear being the oldest. Lartet presented this research to l’Académie des Sciences at their meeting in September 1859, where he made a case for the great age of mankind. Félix Garrigou subsequently added the period “hippopotamus,” which he believed preceded the cave bear period.

Gabriel de Mortillet had published pamphlets in 1848 strongly criticizing king Louis-Philippe and the politician François Guizot and accordingly went into exile in the Duchy of Savoie, at that time not part of France. He became director of the Musée d’Annecy (Haute-Savoie); during his travels in Switzerland and Italy, he became interested in the Neolithic and Bronze Age “lake villages,” retaining his interest in Italian archaeology after his return to France. In 1867, Mortillet was appointed secretary of the Commission for Prehistoric Archaeology at the Exposition Universelle in Paris and the following year was appointed by the newly founded museum in Saint-Germain-en-Laye (Yvelines) to organize the collection of Edouard Lartet and the display of the prehistoric galleries.

In 1869, Mortillet published an essay in which he formulated the first version of his chronology of prehistory founded on the classification of lithic industries. He proposed a new method of archaeological terminology, by attributing objects that are different by reference to names derived from selected sites. Rather than the Three Age System of Thomsen and Worsaae and the modified chronology proposed by Lartet, Mortillet chose technological evolution to determine prehistoric chronology. The names of four phases, namely, Acheulian, Mousterian, Solutrean, and Magdalenian, still are in use. Chellean, which was the name given to the period identified by Garrigou as “hippopotamus” and named from the type site of Chelles (Somme), is outdated, and biface tools from this phase now are classified as Early Acheulian.

Gabriel de Mortillet used the term “Acheulian” to designate the oldest stone tools known in the mid-nineteenth century. In the 1840s, shortly after the discoveries of Boucher de Perthes at Abbeville, a large number of stone tools were found in gravel quarries at Saint-Acheul, a suburb of Amiens (Somme). They were distinguished by a large number of tools made as bifaces—that is, worked on both sides. The site of Saint-Acheul is now presented as an “archaeological garden,” le Jardin archéologique de Saint-Acheul.

The lower of the two rock shelters at Peyzac-le-Moustier (Dordogne), first excavated in 1863 by Edouard Lartet and Henry Christy, is the type site for stone tools of the Mousterian phase. Use of the term was extended outside France, and Mousterian has a wide geographical distribution across Europe, Asia, and North Africa.

The Solutrean type site is the Roc de Solutré (figure 4.3), also known as the Crot du Charnier, which overlooks the commune of Solutré-Pouilly (Saône-et-Loire). The site was found at the base of the rock by Adrien Arcelin, who, with Henry Testot-Ferry, conducted excavations there between 1866 and 1869. Finds suggested that Solutré was a hunting camp, in use for more than twenty-five thousand years, between 35,000 BC and 10,000 BC. Arcelin’s son, Fabien Arcelin, also conducted excavations at Solutré in the 1920s and gave his finds to the Labotatoire de Géologie at Lyon. The most recent excavations at Solutré were conducted by Jean Combier, then director of prehistoric antiquities for the Rhône-Alpes region, between 1967 and 1978. Both Testot-Ferry and Arcelin assembled large collections, particularly Testot-Ferry, whose collection at his death contained more than five thousand objects, many of which were sold by his grandson to the Musée des Ursulines at Mâcon (Saône-et-Loire) and the British Museum in London. Much of Adrien Arcelin’s collection is now in the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, although Arcelin may be best known for his “prehistoric novel” Solutré ou les chasseurs de rennes de la France centrale (Solutré, or the reindeer hunters of central France), published in 1872 under the pseudonym Adrien Cranile, which is an anagram of Arcelin. The novel tells of the legend of horses falling from the top of the Crot du Charnier, pursued by hunters, a story contradicted by analysis of the archaeological remains.

Figure 4.3. The Roc de Solutré. istock, 184450168

Solutrean stone tools were made using by a distinct technology known as lithic reduction percussion and pressure flaking. These techniques enabled the production of very fine tools from thin pieces of flint. The lithic material from the Crot du Charnier was examined in 1869 by Gabriel de Mortillet, who assigned the name “Solutrean” to this type of technology.

“Magdalenian,” dating between 15,000 and 10,000 BC, is named from the Abri de la Madeleine in the commune of Tursac (Dordogne) and is the “type site” for one of the later phases of the Upper Paleolithic in Western Europe. As discussed in chapter 2, the rock shelter was excavated from 1863 by Edouard Lartet, and subsequently by other archaeologists including Denis Peyrony.

The chronology was further subdivided, with the addition of Aurignacian and Gravettian technologies.

In 1852, Jean-Baptiste Bonnemaison, a quarry worker from Aurignac (Haute-Garonne), made a chance discovery of a rock shelter during road making. Inserting his arm into a small opening in the hillside, he found the fossilized remains of animals. Edouard Lartet was alerted to this discovery, and in 1860 he undertook the excavation of the rock shelter. He retrieved much archaeological material, notably worked tools made from stone and deer bone, the remains of a hearth, and the skeletons of animals that are extinct. Lartet presented his finds at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867. In 1906, Henri Breuil first used the term “Aurignacien” and, accordingly, l’Abri d’Aurignac became the eponymous type site of the Aurignacian period, characterized by the material culture from around thirty-eight thousand to twenty-eight thousand years ago. The site became a historic monument in 1921. Further excavations in front of the Abri d’Aurignac were conducted by Fernand Lacorre in 1938 and 1939. Two periods of use of the rock shelter were revealed: one Aurignacian and the other more recent, in the Neolithic period. Today there is a museum in Aurignac, le Musée Forum de l’Aurignacien, which opened in 2014, to replace a much smaller museum of prehistory that opened in 1969.

The term “Gravettian” was used for the first time in 1938 by the English prehistorian Dorothy Garrod in discussing the lithic technology found on the site of La Gravette in the commune of Bayac (Dordogne) between twenty-eight thousand and twenty-two thousand years ago. The stone tools characteristic of Gravettian technology are blades, scrapers, and distinctive points. The site was discovered in 1880, and several excavations took place at the end of the nineteenth century, with the finds dispersed in various museums. The last excavations on the site were undertaken by Fernand Lacorre between 1930 and 1954. The site currently is very overgrown, as it was donated by Lacorre to the French state on the condition that it not be excavated for at least another fifty years.

The study of worked stone tools advanced as a result of the research of the French archaeologist François Bordes (1919–1981). Bordes developed systematic typologies of Paleolithic tools and was the initiator of the method of statistical analysis in the study of ancient lithic industries. Bordes conducted excavations at the well-stratified sites of le Pech-de-l’Azé in the commune of Carsac-Aillac (Dordogne) for two seasons from 1948, and at Combe-Grenal, in the commune of Domme (Dordogne), between 1953 and 1965; it produced fifty-five distinct Mousterian levels. His study of the stone tool industries led him to propose a new way of studying them, founded on statistical analysis, by consideration of percentages of different types of tool. Bordes published his first article on the use of statistical analysis in the study of stone tools in 1950, and his proposal quickly was adopted by researchers in this field.

Underwater Archaeology off the Coasts of France

In the twentieth century, France has led the way in the development of the technology necessary for archaeological excavations to be conducted under water. This archaeological discipline did not progress until the commercial development of a system that used a high-pressure cylinder and a demand valve, which delivers air only when the diver is breathing in. The Aqua-Lung was developed by Jacques-Yves Cousteau, a French naval officer, and the engineer Emile Gagnan. The term “scuba” (originally capitalized as SCUBA), an acronym standing for self-contained underwater breathing apparatus, first was used in 1962 by Major Christian Lambertsen, formerly a physician in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. The SCUBA specifically described the closed circuit rebreather apparatus Lambertsen had developed, although in modern usage the term “scuba” is now extended to include the Aqua-Lung.

The use of the Aqua-Lung by sport divers in the 1940s and 1950s had led to chance finds of ancient shipwrecks and their cargo in the Mediterranean, including dozens of wrecks found off the coast of southern France. However, these were primarily salvage operations, whose aim was the retrieval of antiquities such as Roman amphorae. It was not until it became normal practice for archaeologists to learn to dive that modern archaeological techniques were employed on underwater excavations.

One of the pioneers of underwater archaeology was Philippe Tailliez (1905–2002), an officer in the French navy who had helped Jacques-Yves Cousteau in testing the AquaLung. In 1945, Tailliez was appointed director of the GRS: Groupe de recherche sous-marine (Group for underwater research), from 1950 known as the GERS: Groupe d’études et de recherche sous-marine (Group for underwater study and research); and, in addition, was involved in archaeological investigations off the Tunisian coast at Mahdia. Alongside his naval career, Tailliez is most renowned for his work on the wreck of the Roman vessel known as the Titan. The wreck was found in 1948 at a depth of between twenty-seven and twenty-nine meters off the northeastern tip of l’Ile du Levant, one of the Iles d’Hyères (Var). The wreck initially was surveyed in 1954, but, as discussed further in chapter 5, subsequently it was looted. The wreck was excavated by Tailliez in 1957 and 1958, using underwater recording techniques including plotting finds in relation to a grid system on the seabed. The cargo consisted of around seven hundred amphorae, mostly of the Dressel 12 type, containing fish sauce from Hispania (modern-day Spain). Other finds included some bronze vessels, pottery lamps, Campanian ceramics, and a few coins. The coins, ceramics, and lamps enabled the wreck to be dated to the middle of the first century BC. The wreck also had an example of the tradition of placing a coin inside the socket of the ship’s mast step. Although Tailliez undoubtedly was constrained by his lack of familiarity with archaeological techniques, the excavation of the Titan is notable for the early use of scientific methods.

As discussed in chapter 1, France was the first country with a dedicated government department for underwater archaeology. In 1966, André Malraux, then French minister of culture, created Le Département des Recherches Archéologiques Subaquatiques et Sous-marines (usually abbreviated to DRASSM), based in Marseille. Its original survey ship L’Archéonaute, which had mapped almost a thousand archaeological sites, was replaced in 2012 by a new ship named the André Malraux.

Aerial Photography in Archaeology

The use of aerial photography in archaeology was pioneered by French archaeologists.

Antoine Poidebard (1878–1955) was one of the first people to use aerial photography to research terrestrial and underwater archaeological sites. Born in Lyon, Poidebard was ordained as a Jesuit priest and in 1924 traveled to Beirut to take part in the rescue of Armenian refugees. In 1925, Poidebard was commissioned by the Société de géographie de Paris to fly over the region to find sources of water and underground water courses. During these flights, Poidebard noticed that the raking evening light revealed the remains of structures, and accordingly he devised a method of using aerial photography to record the ancient remains in the Syrian desert. With the logistical support of “l’Aéronautique Militaire,” which in 1934 became l’Armée de l’Air française (French air force), Poidebard subsequently made the first systematic documentation using aerial photography of the ancient roman frontiers of Syria (1925–1932), the port of Tyre (1934–1936), the Byzantine frontiers of Chalcis (1934–1942), and the port of Sidon (1946–1950), in collaboration with René Mouterde, a Jesuit priest and archaeologist, and Jean Lauffray, architect and archaeologist. Poidebard also undertook similar aerial photographic research in Tunisia and Algeria.

René Goguey (1923–2015) first became acquainted with aerial photography while a pilot in the French air force. In 1958, he surveyed the Gallo-Roman sanctuary in the commune of Essarois (Côte-d’Or) and later made plans of the large sites at Alésia, Vix, Mirebeau-sur-Bèze, and les Bolards (all Côte-d’Or). He also discovered several Gallo-Roman villas. In 1968, while still serving with the French air force, Goguey was awarded a doctorate by l’Ecole pratique des hautes etudes in Paris, where his thesis focused on the techniques of aerial archaeology that he had used on the archaeological sites in the Bourgogne region. On his retirement from the French air force in 1973, Goguey continued to conduct aerial surveys, funded by the Direction régionale des affaires culturelles (DRAC) of Bourgogne. In 1976, favorable dry climatic conditions led to numerous discoveries by Goguey, especially a previously unknown Gallo-Roman theater at Autun (Saône-et-Loire). He also conducted aerial surveys in Eastern Europe, as well as directing the excavation of several terrestrial sites. It is estimated that during his career Goguey took around one hundred thousand aerial photographs and recorded four thousand archaeological sites.

Roger Agache (1926–2011), formerly director of prehistoric antiquities for Nord-Picardie, was another pioneer of aerial archaeology, particularly in northern France. Agache began his career working on terrestrial archaeological sites, but from the late 1950s turned his attention to aerial archaeology. One of his earliest, and most important, discoveries was the entrance to a Roman camp on Mont Câtelet in the commune of Vendeuil-Caply (Oise), identified in 1962. Agache was also instrumental in the use of aerial photography during the winter months, when frost can aid the identification of archaeological sites. Among his many publications is the Atlas d’archéologie aérienne de Picardie. La Somme Protohistorique et Romaine, a two-volume work coauthored with Bruno Bréart, which documents numerous sites.

Archaeological Science

Valuable contributions to the study of individual classes of object have been made following the development of more sophisticated analytical techniques. The study of ancient metals in France has been facilitated by the establishment in 2005 of LEACA, Laboratoire d’Etude des alliages cuivreux anciens (Laboratory for the study of ancient copper alloys), directed by Anne Lehoërff, professor of European protohistory at the université Charles-de-Gaulle-Lille-3. Lehoërff’s national responsibilities include acting as vice president of CNRA: Conseil national de la recherche archéologique (National Council for Archaeological Research), a government body that is part of the Ministry of Culture and Communication and deals with matters relating to archaeological research in France.

The Atelier Régional de Conservation Nucléart (ARC-Nucléart), based in Grenoble (Isère), was founded in 1967. It specializes in the conservation and restoration of organic materials and conducts research to develop new methods of treating organic remains. In addition to carrying out projects in their laboratories at Grenoble, staff from ARC-Nucléart work on archaeological sites. Among the archaeological discoveries conserved at ARC-Nucléart are three Gallo-Roman barges: two found at Lyon, the other at Arles. One of the more unusual commissions undertaken by ARC-Nucléart was the treatment of a baby mammoth, found in Siberia in 2009 and given the name Khroma, prior to a temporary exhibition at the Musée Criozatier in the town of le-Puy-en-Velay (Haute-Loire).

The work of French archaeologists has shaped our knowledge of the archaeology of the region, particularly the Paleolithic period in France, including the naming of type sites for phases of that period. In addition, the discipline of underwater archaeology developed thanks to innovations pioneered in France, particularly the AquaLung, which revolutionized the ability of archaeologists to work under water.