CHAPTER 9

PIO

The moon was higher now. It was blunt not crisp, an immense lopsided ovoid emitting soft light into a hazy sky where stars are dim and do not twinkle. Cherry followed Doc and Egan over the drainage ditch by the EM four-holer and up the graveled dusty road toward brigade headquarters. El Paso and Jax had decided to return to their sleeping area but Egan had said to Doc, “Let’s go up to brigade and do our heads a favor,” and Cherry had been pulled along in the excitement which followed the brawl at the Phoc Roc.

“How’s your head?” Egan asked Doc. He stopped the black man in the middle of the deserted road to inspect the cut on his forehead and feel the lump coming up on the back of his head. “You’re okay,” he said. “Let’s see if Lamonte and the dudes are partyin.”

“Them white folk,” Doc said. “Them are some crazy mothafuckas. Sucka’d me right up the backside a my head. Mothafucka. Hey, Man,” Doc said to Cherry and Egan as they resumed walking, “I wanta jus say thank you fo helpin me out a there. That mothafucka nailed the backside a my head but good.”

A few steps farther Doc turned to Cherry. “You handle yourself pretty well. I see you dealin on that one dude and I says, ‘Cherry’s gonna be alfuckin-right.’”

“Them Delta Company mothafuckers,” Egan said looking straight ahead as they walked, “losing their fuckin cool. God fuck. Suckered you but good. Wish I’d gotten a better shot at the mothafucker.”

“Cherry nailed the fucka,” Doc said.

“I’m not sure,” Cherry said glancing first at Egan then at Doc and then back at Egan. “I’m not sure I got it all straight what happened.”

They spoke quickly and quietly as they walked, their words running into each other as the words of men will do when adrenaline is still flowing though the fight is over. “We was jus teasin each otha,” Doc said. “Except fo Jax, Egan here my Main Man. Like best friend.”

“You coulda fooled me in there,” Cherry said.

“We were just discussin,” Egan said. He was embarrassed by the warmth of Doc’s statement.

“You was really dealin on that one fucka,” Doc said. “Eg, your Cherry gonna be al-fuckin-right-on.”

“Hope I didn’t hurt him,” Cherry said. “I’ve never hit anybody like that before. Not that hard.”

“He had it comin,” Egan said.

“I think I might of broken his nose. I felt it crunch. I’m really sorry.”

“Sorry! Sorry, Mista?! You broke that dude’s nose, he gonna be the happiest luckiest mothafucka round. You maybe saved that man’s life, Mista, if you broke his fuckin nose. You know that?”

“Hey,” Egan said wanting to change the subject, “these dudes up here are really into their dope. Don’t be a bummer. Okay?”

“We oughta invite Lamonte out with us,” Doc said. “He’ll wanta go.”

“Yeah,” Egan answered. “Cherry, you know anything bout pot protocol?”

“About what?”

“These dudes really got a rigid way of doin their dew.”

“Ah, you’re losin me. Their what?”

“God fuckin damn. How’d you get to be such a fuckin cherry?”

“Their dew, Man,” Doc said. “You know, like in the morning the dew is on the grass. Dig?”

“Look,” Egan stopped in the road again. He turned to Cherry and stopped him. “There are about ten dos and ten don’ts at a set. Those dudes find it necessary cause a downer’ll wreck a high and that’s UN-For-givable.”

“I’ll watch it,” Cherry said.

“No. Just let me tell ya. After they torch up a bowl be powerful mellow. Like never pass an unlit bowl; never reach for a bowl til it’s passed; never let your rap put the bowl out.”

“Yeah, dig?” Doc added. “Never rap anyone inta a bummer and never keep a dude’s lighter after lightin a bowl.

“Bowls pass to the right up at brigade. Take a toke and pass the bowl. Dig?”

“Hey. Okay,” Cherry said. “If you see me doin somethin wrong, tell me. Okay?”

They continued up the road a quarter of a mile and turned at the break in the low sandbagged wall that preceded the trenches for brigade rocket security. No one was about. It was 0145 hours. Behind them, beyond the Oh-deuce, beyond the perimeter, illumination flares popped and slowly sank against the black wall of the mountains. Up the hill before them were half-a-dozen hootches. At the right end of the line were the quarters for the Vietnamese interpreters then the hootch of the attached personnel then, the APO, the Military Intelligence Office, the PIO and Civil Affairs office and finally the MARS station. All the offices were vacant, the interpreters’ hootch was dark and silent. From the quarters for the attached personnel music drifted, oozed from the glow at the edge of the windows. The music seemed to have a difficult time squeezing through and expanding in the thick air. At irregular intervals the blast of artillery from the batteries deeper into Camp Eagle interrupted the music and the woosh of the mortar flares streaking skyward then popping, igniting and gently whizzing to earth added an eerie harmony to the sounds.

Egan, Doc and Cherry entered the hootch from which the music seeped. The interior had been sectioned off with plywood sheets forming six rooms with a narrow-hallway down the center. A single incandescent bulb lighted the hall. A mural had been crudely painted on the wall of the first room to the left. The scene was a country road running back into green grassy hills with clusters of rounded trees here and there and fences paralleling the road over the hills, in and out of sight, finally disappearing at a vanishing point. A sign in the foreground had arrows pointing in five different directions: Quang Tri-78 km; Saigon-514 km; Big Moose, Montana-19,757 km; N.Y.C.-24,460 km; and one arrow pointing straight up, Moon-386,800 km±.

Wooden ammo crate tops served as cafe doors for the room.

Egan, followed by Doc and Cherry, pushed the doors aside and entered. Inside the room there were three men. They had been talking sporadically. Two of them sat behind a bar on high stools and the third sat on a footlocker turned on end. The bar had been the old bar from the Phoc Roc which the men had scavenged.

The room was dingy. At each end a cot was covered by sloppily hung mosquito netting. Above the cot to the left was a stereo receiver/amplifier and 8-track tapedeck. Above the bunk to the right was a bookshelf full of volumes varying from The Working Press by Ruth Adler and The Information War by Dale Minor to a volume of Shakespeare and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. Hung below each shelf was an M-16 rifle and a bayonet. Below the rifle to the right there hung a crude sign:

IN MANY COUNTRIES POLITICIANS HAVE SEIZED ABSOLUTE POWER

AND MUZZLED THE PRESS;

IN NO COUNTRY HAS THE PRESS SEIZED ABSOLUTE POWER AND

MUZZLED THE POLITICIANS.

The man to the right behind the bar was thin and slight. He had long straight brown hair, longer than regulation. He wore civilian clothes, a western shirt with embroidered shoulders and blue jeans. He was known variously as Lamonte, PIO or Photog. Lamonte was an Army Information Specialist—Journalist, Spec. 4, assigned to the 1st Brigade Public Information Detachment. He was an infantry correspondent and he took himself and his job seriously. He traveled repeatedly with the same twelve infantry companies and he became close friends with many boonierats. Amongst them he was known as the Boonie Rat Correspondent.

Everyone has always portrayed infantryman, boonierat, as dumb. Everyone, except anyone who has ever been a boonierat. Boonierats were not dumb. Lamonte often emphasized this fact in his stories. He liked to tell people, especially soldiers, that the average soldier drafted into the army in 1969 had 14.4 years of schooling. “A junior in college,” he would say. “This army is probably the most highly educated army ever, anywhere.”

Beside Lamonte stood a heavy soldier in jungle fatigues. He was Lamonte’s replacement. He’d been in-country two months though he had only limited field experience. His name was George.

On the turned up footlocker was Le Huu Minh, the Vietnamese scout and interpreter of Company A. Like most Vietnamese he was small by American standards, just over five feet. GIs called him Minh or Little Minh in deference to the South Vietnamese general and political figure known as Big Minh.

Whenever Lamonte and Minh were in the rear together they discussed politics and current events.

“I heard on your radio today,” Minh had been saying in his soft precise English, “your federal tribunal reaffirm your chain-of-command courts.”

“Oh, on My Lai,” Lamonte said. “Yep. The courts ruled … Egan!” Lamonte shouted as the three entered. “You ol’ rattlesnake, good to see ya. Doc! Jesus H., what happened to you.”

“Ah, nothing, Man. Dig? Doan mean nothin’.”

“Yer the first ones to the party,” Lamonte said. “How bout a Coke? You know, if you don’t want to drink anything alcoholic.”

“No thanks,” Egan said shyly.

“We’re goina be up for quite a while tonight,” the correspondent said.

“We come over to ask you out with us in the morning,” Doc said. “What are you doin?”

“That fuckin major. He and that fuckin asshole butterbar lieutenant we got. They keep killin my stories. I’m workin on an article about censorship. But I’m through for the night.” Lamonte stacked the scattered pages, bent down behind the bar and came up with two cans of Coke. “Here. Hey, this is my new cherry, George. This is Egan and that’s Doc and …”

“This is Cherry,” Egan said. “Lamonte,” Egan pointed, “George and Minh. Minh’s from Phu Luong,” Egan addressed Cherry. “You know where that is.”

“I do?” Cherry said.

“Yeah,” Egan said. “Remember when we came in today, with that asshole captain from brigade? Remember?”

“Yeah,” Cherry said. Doc had given Minh a power salute. The two now were power handshaking.

“Remember that village he was rattling on about?” Egan asked.

“I thought you were asleep.”

“I haven’t slept in 17 months,” Egan said. “That village is part of Phu Luong. Minh lives down on one of the criks behind the village center.” Egan turned back to Minh. “You getting round,” he said.

Minh smiled a shy respectful smile. Lamonte opened the sodas and handed them across the bar for the men to share.

“No,” Egan said, “I think I’m imposin on you guys. We just come over to tell you we’re ruckin up at oh-four hundred. We don’t want to impose on you.”

“You just think you’re imposin because you don’t understand, Man,” Lamonte said.

“You know what it is?” George chuckled.

“He’s in bad shape,” Lamonte nodded toward George.

“Yer standin on that side of the bar,” George chuckled again. “By yerselves.”

“That’s what it is,” Lamonte agreed. “Why don’t you shut the doors. If that hall light wasn’t on out there this place would look real cool.” Lamonte took a tensor-lite from the bar and placed it on the stereo shelf with the beam aiming at the ceiling! “Why don’t you go out and shut off the light, George?”

With the hall light off and the tensor beam against the ceiling the room lost its dinginess and became almost cozy. “Where you all from?” George asked.

“Oh-deuce,” Cherry said with private pride.

“How long you all been in-country?” George asked.

“Shit, Dude,” Lamonte interrupted. He pointed at Egan, “That man’s been here since before I was. Man, Egan was a cherry way back when Christ was a corporal. And Doc! God! Doc came here right after Genesis. Doc, you don’t look too good. How you feel?”

“Man,” Doc expelled the word from his throat after taking a swallow of Coke, “my head burn and I feel all this pressure on it. But Man, my body is cold, dig? And I got a mean case a the chills and my feet is freezin. I’m five thousand years old, Man, an I feels like a five-thousand-year-old piece a shit.” Everybody laughed and Doc laughed the hardest.

“I got somethin to fix you right up,” Lamonte said, smiled and the others laughed again. “We got a new, super-mellow one-hit bowl and some stash that’ll warm ya up and ease the pain.”

George reached up behind the books in the shelf and produced an eighteen-inch-long bamboo tube. The tube was almost two inches in diameter. The bottom was sealed by a natural sectioning of the bamboo. The top sectioning had a small hole drilled in it. About midway up the side of the tube a tiny carved bowl on a long stem had been inserted at an angle into the only other orifice in the tube. George handed Lamonte the pipe and Lamonte carefully, methodically, removed the bowl and stem from the tube and laid the tube on the bar. From under the bar he produced a bottle of white wine. He very slowly poured wine into the orifice in the tube gradually raising the top so the wine did not spill out from the mouthpiece.

“Where you going out to tomorrow?” George asked Egan.

Lamonte gazed up at George in amazement at the inappropriateness of the question. Stoned George was oblivious.

“Just into the boonies,” Egan said. He looked distrustfully at Minh from the corner of his eye. Then he turned to Minh, “You comin out?”

“Yes,” Minh said. “I am ready. I will be on the pad when the helicopters arrive.” Minh’s voice was an octave higher than Egan’s. He spoke English more precisely than most American soldiers though he added an intonation to the words which made his speech oddly like singing. He was proud of his diction and extensive vocabulary.

Lamonte gently placed the bowl stem into the tube and then filled the tiny bowl with finely ground marijuana leaves. He handed the pipe to Doc. “Let’s get your head squared away,” he said. Doc took the tube and holding it at an angle so the bowl stem was in the wine but the wine was not high enough to flow up the stem into the bowl, he placed his mouth over the upper end of the tube. Lamonte clicked his lighter and held the flame over the bowl as Doc sucked. The dried leaves glowed to amber red coals. The smoke bubbled through the wine then cooled in the air chamber below the mouthpiece finally passing through and into Doc’s expanding lungs. The coals died. Doc shut his eyes, held the gases in and handed the tube back over the bar to Lamonte who reloaded the bowl.

“Damn,” Doc opened his eyes wide, exhaled and bellowed, “that’s one mean mellow bowl.”

Lamonte handed the one-hit bowl to Egan and fired it as Egan sucked then reloaded it for Cherry, George and finally himself. Little Minh declined to smoke which was typical of all the 1st Brigade Vietnamese interpreters and scouts. Smoking, like drinking alcoholic beverages, was a very social way of relaxing in the rear-areas. The men who smoked usually maintained a lower profile than the men who drank. There were men who only drank and others who only smoked, the juicers and the heads, but most men did both and some men did neither.

Lamonte and the crew laughed and joked and passed the bowl several more times. Then Egan took some OJs from his pocket and they passed the opium joints around until everyone was feeling very relaxed and introspective.

Cherry picked up some papers Lamonte had written and read them slowly, concentrating on the images of each word, each letter of each word. The dope gave him a pleasant tight sensation at the temples and across the top of his head. Slowly he pieced it all together.

‘Hello Kiddo.’ That’s a line from a movie I saw about four years ago. ‘Hello Kiddo, Kiddo hello.’ I think it was David and Lisa.

Lots of things have been happening around here. So many things that I’m dying of boredom. Brian Thompson got killed yesterday. Bill Martin caught a piece of shrapnel just below the navel but it wasn’t too bad and he didn’t even have to be medevacked. They’re allowing him to stay in the field with all his buddies who all want to look for the NVA who killed Brian Thompson. As a matter of fact they are going to look for any NVA and try to shoot and kill them. Brian Thompson or no Brian Thompson, they’d probably do it anyway. They killed three soldiers, NVA type, today. They probably were not the ones who got Brian but if they could have gotten Brian or Bill they probably would have. Not any more, though.

Lots of people have been killed in the last few days. Probably some of them were from Colorado. Probably some of them were killed in Colorado or Kentucky or even California. Some of them weren’t even in the Army. Some of them were probably too young or too old to be in the Army or the Navy or even in the Air Force for that matter.

Isn’t it wonderful the ways, all the ways, that people die? And just think of all the stuff people will do for you after you die. Why, as I understand it, somebody will replace all your bodily fluids with formaldehyde and other good tasting chemicals. Then someone will put you in a plastic bag. That isn’t really for you. That’s for other people. They don’t want to smell your BO.

Arnie Thompson, he’s not related to Brian … Brian is a black man or was a black man … Arnie is a white man and still is, all of Arnie except his liver which he has succeeded in turning black with some stuff you can buy over here in a bottle … you can buy it back there too … Arnie was telling me last night about Lieutenant Anderson. Lt. Anderson was a devout Mormon, Arnie said. I didn’t know the lieutenant. The day before the assault on Ripcord, Arnie told the L-T that he’d kill him if he ever left the body of an American up on a hill. Evidently the L-T had done that on an earlier assault attempt.

So the next day the lieutenant is a changed man. And he’s got the courage to charge up the side of Ripcord … For the Glory of the Infantry. Someone had earlier suggested to the generals that they withdraw all allied troops and send in air strikes and B-52s and stuff like that but the generals wanted the victory of Ripcord for the Glory of the Infantry, too.

So, L-T Anderson from someplace in Indiana and his men go up the side of Ripcord to reinforce the sieged troops at the top, up ol’ Ripcord with the pride of the Queen of Battle. Arnie never said why the generals wanted them to assault up the side of Ripcord. He never told me why they didn’t just pick up his company and fly them up there and let them assault down if they really had to assault. Anyway, Joey, L-T Anderson’s RTO, gets lost or something. Actually he had his head splintered. Not bad enough to kill him. Arnie found him at the bottom of the hill later. Good Mormon Anderson is up on the hill looking around for Joey when he gets his right arm and left hand and both legs blown off. “My arm, it isn’t there,” he says to Arnie. “No Sir. Your arm isn’t there.” “And my hand is gone too,” Anderson says. “Yes Sir. Your hand is gone too,” Arnie tells him. Arnie had tears in his eyes as he told me this. I’d been feeding him wine and scotch and listening. I wasn’t drinking myself because I had a bad case of the shits.

“Well,” Arnie says, “I wrapped up his arm and his legs and called for a medevac but they were all busy and it was going to take some time.” Arnie’s been around for some time. He’s old. Maybe forty. His face is pockmarked.

“It were two hours later that man died,” Arnie whispered with tears rolling down his cheeks. There were not a lot of tears. Just one on each side. Arnie isn’t the kind of man to bawl. “That man died right here,” Arnie said holding out his arms. “Right here, of a sucking chest wound that he didn’t tell me about,” Arnie said.

And it was all so they could go up the hill and kill some North Vietnamese who were there only to kill some Americans or some ARVNs or maybe a ROK or two. Lt. Anderson never did find Joey. Joey is back in the World now. Arnie was saying he’d kill a man if he ever left another man behind on the battlefield. Isn’t it wonderful what people will do for you after you are totally unable to do anything for yourself?

They’ll do even more for you than that. They’ll get your insurance money and spend it on a lot of flowers and on a great hulk of marble or granite and on a hole in the ground. Maybe there will be a little left over for gas money so they can go to the movies and forget why you died.

Come to think of it, it was David who said to Lisa, ‘Hello, Kiddo, Kiddo hello.’ Yes David who wouldn’t let anyone touch him and Lisa who was so into poetry she would speak only in rhyme, and everyone thought they were crazies.

The real crazy was Brian Thompson. I was talking to him the night Delta Company had a ground attack on their position. That was two weeks ago. Delta was on the hill across from us. We felt sorry for them and very helpless because we couldn’t help but could just listen to the firefight all night long. That night Brian told me he wanted to get the Medal of Honor. ‘They’s gointa put me in for it cause a the way I react in the field,’ he said. Later I asked the captain if any of his people were up for medals and he said no. “Lots of the people in the company now are cherries,” the captain said, “and we haven’t been making a lot of contact. I had one man who DEROSd who is in for a Silver Star but none of the men we have now.”

Cherry looked up from the pages. He looked at Lamonte and at Egan and Doc and George, all who were laughing at something George was doing. Minh was laughing too but his laughter was more subdued because he was not stoned. Doc passed Cherry his OJ and George passed Cherry half an oatmeal cookie.

“You really got a rap, Man,” Lamonte said to George. “No foolin, Man. But it sure took you a long time to say that.” The opium and marijuana slowed all their speech considerably and it shortened their attention span.

“Oh,” George groaned to the general laughter. “Open up a can of tamales, Man. We got a can of tamales.”

There was more laughter and Cherry laughed too although he was feeling strange from what he had read and from the dope. He did not feel a part of the group any more. Lamonte opened the can and dumped the contents onto an old, broken china plate on the bar. “Wow! We’re goina have ta cut these into threes,” he said.

“I do not like tamales,” Minh said.

“Good,” George said. “Then we can cut em up into two-an-a-halves.” They chuckled again. “I told you that thing about ‘you cut—I pick,’ didn’t I, Lamonte?”

“I don’t know but I was just cuttin on this thing for about five minutes with the back side of the knife.”

“You still are,” Egan laughed.

“There is a collusion set up against you, Lamonte,” Minh said.

“Is that your word for today?” George asked.

“No. That one I learned yesterday.”

“Doc. Here,” Lamonte said passing him a tamale slice. “No. Doc,” he said when George reached for it.

“I’ll pass em around,” George said.

“There you go,” Lamonte said as he passed out the remaining slices. “Augh … that’s no fair. I got a nub on mine.” Then he added in falsetto, “Devil made me do dat.”

“Hey,” Doc said seriously, stoned serious. “You all pretty educated. Maybe you can tell me. I’ve asked sergeant majors, majors, captains, lieutenants, EMs, buck sergeants, master sergeants. Why do the army do this shit? Huh? Huh?”

“What shit?” Cherry asked.

“It’s bad enough we gotta come in the army and then leave the army and depart our friends. But the war … Why? Give me one good logical goddamned reason, Mista. One.”

“The war come, ah, the war comes before the army, ya know?” George said. Lamonte glared at him and shook his head and George added, “Well, maybe not.”

“I mean, like all the people you know in the World,” Doc said simply going on, oblivious to George, “Blond who used ta be up there. Way down there. Great guy, blond hair. Use ta always be drunk all the time …”

“Yeah.”

“Do you know me en him been here since ’68 tagether. I was in the Cav, Airborne Infantry. In the Elephant Valley up north.”

“North of the A Shau?”

“Walkin,” Doc said. “Walkin. Walkin toward the A Shau Valley. And after we left the A Shau we were supposed ta go ta the Ruong-Ruong. Which we did. They all three is right there, right?”

“Yeah. North, middle and south,” Lamonte agreed.

“Do you know when Blond said good-bye ta me tanight, no Man, two nights ago, both of us cried, Mista. I’m not bullshittin. He was on the mothafucken LZ when I got those two SKS rounds in my legs. I was there on the chopper pad. I saw him. I met Blond before, on Firebase Geronimo when he was with Seventh a the Four-Oh-Deuce. Recon. Both a us cherry in-country: 1968. But he was here before me an … well, he was here bout three month before me. He got here round August a ’67. I got here November 17th, 1967. I left March … March 22d, 1968. I got wounded January, ah, January … ah … I fergot the date. I try ta keep it far from my mothafuckin mind. Like you nevah hear me talk bout it, right?”

“Right.”

“I see Blond on Geronimo the day I got wounded. When I was goan out in the chopper, one Power Sign, one Peace Sign.” Doc held up one clenched fist and one V-fingered hand. “I’ll see our brothers later. Right? I didn’t go ta Japan. I didn’t go ta the Philippines. I didn’t go ta Korea. Ya know, those big hospitals. I went to Cam Ranh Bay en came right back. Right back. Dig it?”

“Yeah.”

“I was Medic. I was medic humpin. Ya know what I mean? I was medic with the 1st Cav. Combined operation. Recon jus walk off Leech Island. Went ta Curahee. Dig?”

“Yeah.”

“They was comin off Curahee goan toward Berchesgadten. And they radio inta Berchesgadten an say they was comin in. Berchesgadten say, ‘Don’t even come here. We gettin hit.’ They had ta turn around and come back. They radios in and says they comin back. They say, ‘Don’t come back here, we’s gettin hit.’ I’m hearin all this conversation. Dig it? Blond was walkin slack. That time he was walkin slack. They had a brother … black guy like me … Black Brother, ya know what I mean? Man, listen. Him en Blond, he was walkin behind Blond an a RTO was walkin right behind him. I’m not bullshittin ya. We was walkin down the Hoi Sanh Trail. Okay. Blond, they was comin up the Hoi Sanh Trail. We was comin down the Hoi Sanh Trail. We dug a trail watcher. So instead of sayin the trail watcher saw us … most likely he know we saw him, that’s why he dee-deed, we didn’t go chasin him cause it was comin on night, the L-T says, ‘Let’s move up above bout maybe 250 meters.’ Good thing we did. Cause that night, that night, Mista, that night, that spot where we seen that mothafuckin trail watcher at, got fucked up.”

“Mortars?”

“Mortars, RPGs, frags, everythin. B-40s was comin in on that mothafuckin spot where we started ta stay. It’s a good thing that the L-T had sense. Dig it?”

“Right.”

“En the dude says, ‘Blond, Look Out! RPG!’ He hit Blond in the back a the head with his M-16. Blond fell ta the ground.”

“Blond, that guy in radar?” Lamonte asked.

“Yeah. Me en Blond was humpin tagether from ’68. Blond en me, we hugged each other, kissed each other. Ya know Man, like this, side-ta-side. We shook each other’s hand, Man. Man, shake my hand. Ya know? Shake my hand. Ya know, we shook each other’s hand. Ya know what I mean. I put his hand ta my heart, Mista PIO, like I got your hand ta my heart and I says, ‘Blond, do ya feel it.’ He say, ‘Brother Doc, I feel it.’ I says, ‘Guess what Blond?’ I says, ‘You got soul.’ He say, ‘Brother Doc, you been wantin ta tell me that fo a long time.’ I says, ‘Yeah Blond, I know it.’ En he say, ‘En I’m goan home now en I know you really mean it. If you had told me any other time before this, when even we was humpin back in ’68, fightin, ya know,’ he says, ‘I would a had some kind a doubt, some kind a thought. But I’m goan home now and I know that you really mean it.’ I put my hand to his heart. This way. En I say, ‘Blond, I really feel it.’ En Man, we cried. Right there in his mothafuckin hootch, jus a while ago, Man. We cried. We actually cried, Mista. I’m not bullshittin ya.

“Why do the army do that, Mista? Why? You all pretty educated. You tell me.”

“No, Man,’ Egan said. “Doc, nobody can tell you why. It’s just like that.”

“Hey, Mista PIO, you tell me.”

“No, Doc,” Lamonte said. “I can’t tell you neither.”

“You know, Man,” Doc said. “We got us a new cherry here, a new white cherry who gonna be oh-fuckin-kay. Lots a white dudes okay. Dig? Lots a Brothers okay too, Man. Dig?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah.”

“See, but when they get back ta the World we all turn inta mothafuckas. You know what I’m sayin? Man, you know what I’m sayin? Why? Tell me why, Mista?”

“Don’t mean nothin,” Egan said. He removed two OJs from his shirt and handed one to Doc and one to Lamonte and lit them both.

“I think it is time you all go,” Minh said from the far end of the bar.

“Yeah, I think so too,” George said. “It’s three-twenty. What the fuck you guys doin in my AO at three-twenty?”

“No,” Minh said. “I mean it is time you all leave my country and let us work out our separate peace.”

“Minh,” Egan said, “you know, if we were all to leave, even if we negotiate a separate peace, that won’t mean peace for your country.”

George mumbled, “That’s like oh three-hundred and twenty.”

“This is true,” Minh said. “But, my friend Egan, then the war will be a Vietnamese war and not an American war. Your money is too much and now I do not recognize my own home. Your president must have you leave.”

“Oh-three-two-zero,” George muttered. “Up at oh-four-three-zero.”

“Man, you really out of it,” Lamonte said to George. “You are really wasted.”

“Time to sky up,” Egan said lifting his body as though he were lifting a great bulk weight.

“One more hit,” Lamonte said. His eyes gleamed. “Get the shotgun.”

“Oh shee-it,” Doc laughed. “You gonna blow his mind away.”

The shotgun was a tube of seven Coca-Cola cans taped together end-to-end. Grass, bulk marijuana which could be purchased by the sandbag for ten dollars MPC, was burned in the second can. The shotgunner blew into a large opening in the first can and the smoke flowed and swirled up and down and cooled in the five following tins until it peed out a tiny puncture at the end of the tube, until it sniped put in a thin straight line where the shotgunnee could stand back eight or ten inches, mouth gaping, and swallow the smoke stream.

Lamonte loaded, lit and fired. The shotgun worked its way about the room, Lamonte shotgunning his honored guest, Doc. The Doc gunning Egan and Egan George and finally George gunning Cherry. Cherry couldn’t stand after the hit and Egan gunned Lamonte and Lamonte reloaded the tube for a second round.

Cherry sat on Lamonte’s cot and stared into the room and beyond. What am I doing here, he thought. I’m just a kid, just a dumb kid. These are just kids, he said the words inside. The thought was a jumble of words and phrases, of pictures whirling and of names as ideograms. Kids from the suburbs, he thought. Rich kids. We’re kids who’ve dreamed of far lands and exotic places, of the lands and wars of Hemingway and Mailer. Kids dreaming of seeing hobo jungles and shanties and of jumping a Steinbeck freight and of seeing America and the world. I’ve seen Daytona and Ft. Lauderdale at Easter and Cheyenne during the Round-Up but I never saw a dust bowl or mass poverty like the descriptions of the Depression by my folks or by the television. How the hell does an American middle-class white kid see what life is like if they get rid of all the rough edges? Shit. The L-T is as middle class as I am. And Doc. That’s not poverty he comes from. Or El Paso, a low class peasant? With a college degree? A year of law school? That’s not poverty. Jackson? Maybe. But he’s makin the almighty greenback right now more en me. Spec 4. That’s about four-hundred a month with combat and overseas pay and he’s gotta be gettin an allotment for his wife and he’ll get another hundred for his kid. Maybe six bills a month. Then poverty’s gone. So come to Asia and see the poverty. See the poor fuckin gooks with their Hondas.

The music in the hootch was turned up. It blared in through his ears. Now he could not feel his body. Everybody was laughing at him. Everything was sprinting in his head. Everything was clear, so clear. He squinted and the candle flames starred and shot rays in every direction. A flat star first, lines, a halo, glowing growing into a sphere halo and the lines glowing exploding fuzzy clear beams shooting speeding toward him, fire reaching penetrating his eyes. Cherry closed his eyes. He could see the future. The light revolved, rotated, the light stood still and he revolved and rotated. He tried to duck the light then the colors. All colors. They were all giggling at him now.

“Oh, the colors,” he moaned.

They all laughed harder.

“Oh, the colors,” he bellowed. “The colors. They’re … they’re speeding right through me. The fire is speeding through you.”

“Jesus, Egan,” Lamonte chuckled, “you got a super cherry. He’s really funny.”

“Come on, Cherry,” Doc picked him up. “You gettin silly.”

Cherry put his arm around Doc’s shoulder. “Colors, wonderful colors. Colors with jelly. Covered with jelly.” He began chuckling then laughing hysterically.

“He’s cool,” Lamonte laughed. “He’s really all right.”

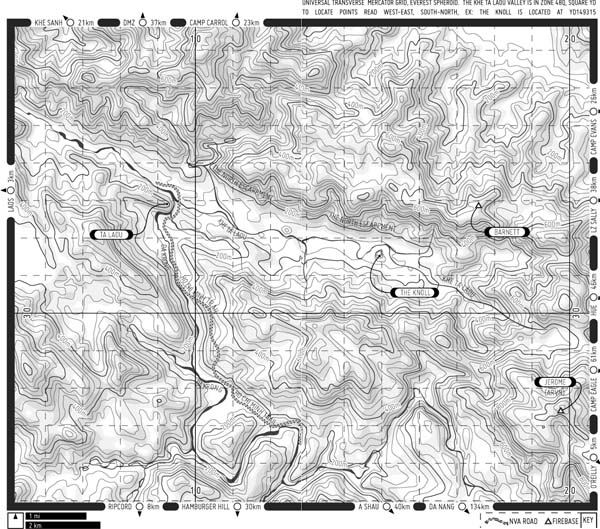

In five hours they would be high again, this time in the air, CAing to the Khe Ta Laou River valley.

AUGUST 1970

SIGNIFICANT ACTIVITIES TO DATE*

THE FOLLOWING CUMULATIVE RESULTS FOR OPERATIONS IN THE O’REILLY/BARNETT/JEROME AREA WERE REPORTED FOR THE TEN-DAY PERIOD ENDING 2359 12 AUGUST 70:

97 ENEMY KILLED, 15 BY US—82 BY ARVN; 18 INDIVIDUAL WEAPONS CAPTURED BY ARVN; 14 CREW SERVED WEAPONS CAPTURED, EIGHT BY US—SIX BY ARVN. FIVE ARVN SOLDIERS WERE KILLED IN ACTION AND 33 WERE WOUNDED IN ACTION. US CASUALTIES WERE TWO SOLDIERS WITH MINOR WOUNDS.

ON 11 AND 12 AUGUST A TOTAL OF 112 ENEMY WERE KILLED AND 17 CAPTURED IN THE VICINITY OF FS/OB O’REILLY. SMALL ARMS CONTACT BY ELEMENTS OF THE 1ST AND 4TH BATTALIONS, 1ST REGIMENT (ARVN) ACCOUNTED FOR 19 ENEMY KILLED. THE 2D SQUADRON (AMBL), 17TH CAVALRY (101ST) KILLED 23 AND TACTICAL AIR STRIKES (USAF) AND AERIAL ROCKET ARTILLERY (101ST) KILLED 70. ONE ARVN SOLDIER WAS KILLED AND 11 WOUNDED DURING THE TWO DAYS OF CONTACT.

* Throughout the book, “Significant Activities …” have been adapted from Defense Documentation Center document AD 515195:101st Airborne Division, Operations Report—Lessons Learned for the period ending 31 October 1970; declassified 11 November 1977.