CHAPTER 10

13 AUGUST 1970 STAGING

The moon was yellow, low on the horizon, just above the blackness of the mountains. Straight up was blue-black. Eighty-four men sat, leaned against their rucksacks, lay on the ground with the chill of the earth passing into their muscles and bones, eighty-four men trying to catch a few moments sleep, trying to have time pass without tiring them more than they were already tired. They lay quietly in the deep monsoon-carved gullies surrounding the landing strip, trying not to think, trying to sleep on the gravel and stone and hard clay of the ravines of the staging area. Twenty soldiers in this ravine; thirty in the next; twenty-four in the one across the landing strip. A few sat back-against-back on the tiny hard ridge dividing the ravines, sat smoking, the faint glow of cigarettes swinging in the darkness.

To Chelini the strip looked like an eighth-mile mini-dragway; to Jackson like an oasis above the ground mist cloaking the surrounding rice swamps; to Minh like an immense multi-legged dragon with eighty-four sucklings squeezing and squirming in the gullies of its legs. The monsoons of last winter had eroded the sides of the strip and gullies had cut deep into it and had grown to sharp V-shaped ravines. The dry season sun had baked the ocher clay and red stone gravel into one solid narrow mesa. The strip had been grated and rolled flat but the lesions had been allowed to remain for they served as trenches.

In the darkness of the pre-dawn a second wave of CH-47 Chinook helicopters approached the staging area. Nothing at first, only a feeling of their nearness. Then powerful headlight beams visible high over the South China Sea, then a slight vibration in the air, then the harsh slapping of rotor blades spanking the sky. Men unable to shut their eyes, to keep them shut, to keep from watching the approaching helicopters, to keep from feeling time’s slow forward pacing.

On the strip a strobe light flashed, an RTO spoke directions into the handset of his radio, moving in the flashes like a character in an ancient film flickering. The dark silhouettes of the birds grew in the sky, the noise became larger enveloping the strip in quick pulsations, shattering the air. Chelini watched fascinated, as pathfinders guided the birds in with long red-dipped flashlights. The strobe went out, the helicopters descended, hovered, descended. In the blackness of the trenches men hid behind their rucksacks and pulled their shirts up tight around their necks. Some men covered their heads with olive drab towels. Cherry watched naively. The rotor wash from the big birds sent dust then sand and stones hurling from the landing strip into the trenches. The birds set down, tails opened releasing more infantry troops, more boonierats scurried to the protection of the trenches. The helicopters lifted and blasting sand lashed the ravines again.

“Okay, People,” someone yelled. “Down here. Charlie ‘Company down here. Don’t go mixin up with Alpha.”

Again it was quiet. The men in the first ravine rolled back, shook the sand from their hair, dug the sand from their scalps and from under their shirts, rolled back onto the hard gravel, exhaled the smell of jet exhaust, lay and attempted to rest. Cherry spat dirt from his mouth and tried to clear his eyes and ears of the sand. Now one hundred fifty-two infantrymen waited, rested, waited restless.

The sky grayed. At the helicopter pad on the ridge above the battalion base at Camp Eagle a Huey helicopter arrived and touched down. Supply personnel, hunching beneath the rotors, carried armloads of OD green equipment to the bird and stacked it on the steel floor. An operations officer and a supply NCO boarded and the Huey lifted. Two companies of the 7th Battalion, 402d Infantry had already rucked up, boarded the large CH-47s and had flown to LZ Sally. At 0605 hours, first light, the third wave of Chinooks departed Camp Eagle for the twenty-eight kilometer flight to the combat assault staging area.

The staging area for the combat assault was on the western edge of LZ Sally, a tiny outpost situated between the sprawling headquarters and base camp of the 101st at Eagle and the division’s 3d Brigade base at Camp Evans. From the staging area the third flight of CH-47s looked like a line of awkward sea gulls. They approached from a point over the Tonkin Gulf where land, water and sky merged to a long thin green-blue-gray line. Again the Chinooks became larger, distinct in the graying sky. Again the air broke with the deep slapping noise from the blades.

“Oh God,” Cherry muttered to himself. “Here they come again.” He rolled on his side, his rucksack between him and the landing helicopters and he watched the monstrous OD bellies drop slowly, watched the sixty foot rotors blur until the wind and dust became so violent he had to close his eyes tight and wrap his arms about his head and bring his knees to his chest to keep the wind from penetrating.

Three companies ordered themselves in the ravines. Two more companies, three scout dog teams and three sniper teams were scheduled to arrive by 0800. At 0817 the combat assault to the Khe Ta Laou River valley would begin.

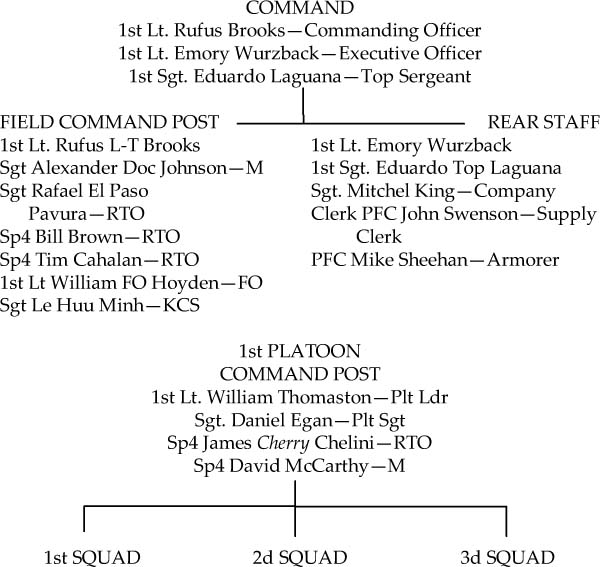

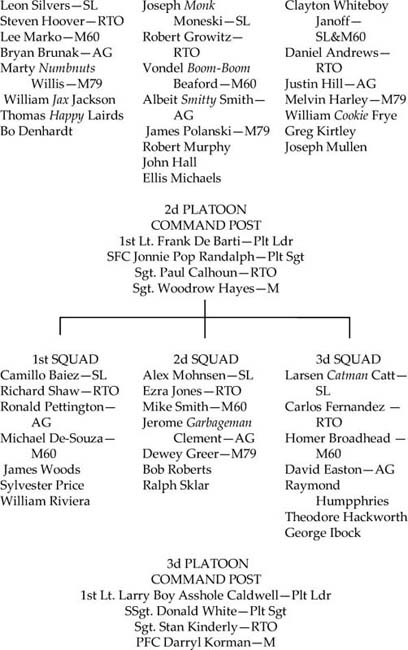

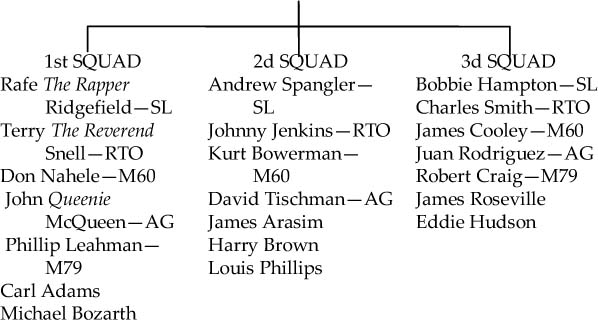

On 15 May 1970 the 7th Battalion, 402d Infantry was reorganized under Department of the Army TO&E 7-35F. Headquarters and Headquarters Company was organized under TO&E 7-36F and the rifle companies under TO&E 7-37F. A few months later Companies D and E were added. Company E was a weapons support element with 81mm mortars and 90mm recoilless rifles. A reconnaissance platoon that was designed to work as a highly mobile rifle platoon or in six-man recon teams under direct control of the battalion commander was attached to Company E.

Officially an airmobile infantry battalion organized under these TO&Es at full strength had the capability to: close with the enemy by means of fire and maneuver in order to destroy or capture him; repel enemy assaults by fire, close combat and counterattack; seize and hold terrain; conduct independent operations on a limited scale; maneuver in all types of terrain and climatic conditions; and to make frequent airborne assaults.

At full strength the rifle companies fielded 121 men plus six attached personnel. A company consisted of three platoons and a command post. Each platoon had three 12-man squads and a platoon CP. A squad consisted of seven riflemen, a thumper man (M-79 grenade launcher), an M-60 ma-chine gunner and an assistant gunner (the AG carried an M-16), an RTO (carried an M-16) and the squad leader.

Platoon CPs consisted of the platoon leader (usually a 1st lieutenant), a platoon sergeant, a medic (attached) and an RTO. The company CP was headed by the company commander and had three RTOs. Attached to the main CP were the company medic, an artillery forward observer (usually a lieutenant) and a Kit Carson Scout, a Vietnamese interpreter-scout-liaison.

On 13 August Company A was at 68% strength. This was typical of the entire battalion. Bravo Company was at 70% strength, Charlie at 59%, Delta 66%, and the Recon Platoon of Echo at 74%. HHC stationed at Eagle was at 81% strength.

A military unit tends to have a character of its own, an identity comprised of its history and traditions and of the personality of its commander. A squad becomes an extension of the squad leader, a platoon a compromise of the platoon leader and platoon sergeant; and the company, the body of the captain or lieutenant who leads it. Battalion tends to be the last level where the brunt of a commander’s whims, likes and dislikes are felt by the individual soldier; yet even at brigade level the colonel marks the collective personality of the units below and again at division and corps and army. At the beginning of August 1970 there were 403,900 US military personnel in Vietnam: 293,600 Army, 22,600 Navy, 48,200 Air Force, 39,300 Marines and 200 Coast Guard; all deriving a multifaceted American personality from the leadership of MACV in Saigon and from the Pentagon and Joint Chiefs and on up to the President, Commander in Chief of all US military forces.

The division personality of the 101st was hard-ass spartan, perhaps the most spartan of all army units in Vietnam. The division ethos was purposefully directed and developed from the style, zeal and esprit de corps of the airborne of World War II. Tradition, heritage, rugged, tough and Airborne All The Way; that was the 101st Airborne. The 101st had stormed through Europe at Eagle’s Nest and Berchesgadten and Zon, had endured the Battle of the Bulge at Bastogne with General Anthony C. McAuliffe’s famous ‘Nuts’ reply to German demands for surrender, had jumped into Normandy on D-Day. In Vietnam the firebases were named after World War II locales and slogans: Veghel, Bastogne, Eagle’s Nest, Ripcord, Airborne, Checkmate, Rendezvous and Destiny.

In 1969 the division became Airmobile and by 1970 most of the troops no longer were hardcore jump-qualified paratroopers. However, most of the senior officers, the leaders, were.

Lieutenant Colonel Oliver Henderson, the GreenMan, ran the 7th of the 402d. He was a strong commander. The stronger a commander the more he affects the men he commands. Henderson ran the 7/402 with stern exacting leadership. He allowed himself few luxuries and he allowed his troops none. Henderson seemed to be unaware of American troop withdrawals and the winding down of the war. He was busy fighting. His ‘SKYHAWKS’ battalion was a proud fighting unit.

Each infantry unit had a particular spirit of independence. This too was planned. Each company, each platoon, each squad and each man was independent and responsible for himself or itself, first and then responsible up the chain of command, link by link. The infantryman, infantry unit, ultimately, like no other military entity, operates alone. Some commanders expected their soldiers to execute orders like automatons but this, especially after the expose of My Lai, was neither the official nor the most prevalent style and it was not the GreenMan’s style. Soldiers were expected to follow orders but they were also expected to know the rules of the host country and of international warfare. If a superior did not follow the rules a soldier was expected to protest. More often soldiers were expected to interpret their own situation to determine the optimum course to accomplish the military objective. As an outgrowth of My Lai, no longer was an American soldier able to excuse barbaric actions by saying, “Sir, I was only following orders.” The GreenMan strongly emphasized that each individual was part of his own leadership and he was responsible for his actions.

The following chart outlines the organization and personnel of Alpha Companny, 7th Battalion of the 402d Infantry (Airmobile) on the morning of 13 August 1970. Symbols:

| AG—assistant gunnner | M60—machine gunner |

| FO—forward observer | M79—thuumper man |

| KCS—Kit Carson Scout | RTO—radioman |

| M—medic | SL—squad leader |

During the pre-dawn Cherry had lain bewildered and silent in the trench at LZ Sally. He had been silent yet he had wanted to talk. He had contemplated asking Jackson something but he could not think of anything to ask. He could not rest. The anxiety about the coming combat assault had caused his muscles to tighten, his stomach to squeeze.

He had been up at 0400 hours. Then it had been hurry up to chow, hurry up and pack, hurry up lug that crazy ruck up the hill from the battalion area to the Oh-deuce pad then wait. At 0440 he had hurry-upped into the Chinook and at 0503 he had hurry-upped out of the bird and into the trench. Then he had waited. “Hurry up and wait,” he had muttered. “SOP. Standard Operating Procedure.”

Throughout it all no one had spoken to him. It was as if he had never met them. It was as if he had not spent the entire night drinking and smoking and talking to them. Again he was an outsider.

It was still cold in the trenches and it was uncomfortable. Restlessly he fiddled with his helmet, his weapon, the radio in his ruck. He fiddled self-consciously, quietly, trying not to disturb anyone, hoping someone else nearby would be fiddling with his equipment also so he could speak. Cherry lay back and closed his eyes. He tried not to force them to stay shut but tried to allow them to remain closed of their own relaxed accord. His eyes would not cooperate.

The sky grayed. The silhouette of mountains to the west turned green-black where the lifting darkness accentuated ridges yet remained jet-black in the canyons. Within the ravines darkness still hung. Laconic chats and extended grumbles disrupted the close silence, the tiring rest.

Doc was suffering hangover pains and pains from the lump on the back of his head and the laceration on his forehead. The thought of the open wound irritated him. “What a sucka. Man, a cut’s a real sucka. Fuckin helmet rub it and keep it open for all them bacteria. Mothafucka gonna get infected. Can’t wear no fuckin helmet.” Doc tied his helmet to the top of his rucksack, shook the pack to be sure the helmet was secure and that it would not rattle when he walked.

“That a good cut, Doc,” Jax said. “Wish I had a cut like that. I think I’s catchin cold. That good too.”

“You need somethin fo it?”

“No way. Not yet. I got this cold now an I’s gowin keep it.”

“You need somethin.”

“I needs this cold, Man. Sound pretty bad, huh?”

“Sounds bad.”

“Like bronchitis?”

“Gettin there.”

“Yeah. Good. In three or fo days I get pneumonia. Gotta keep smokin.”

“There’s mo cig’rettes up in the Sundry pak.”

“Yeah. I’s got get me sah mo. Yo need any?”

“I got em.”

“Ef I’s get pneumonia in a few days you gowin send me in on resupply fo a week a bed rest.”

“If you gets pneumonia.”

“I’s bet I can pull that out ta a month profile,” Jax said. He pulled out his hair pick and fluffed up his ‘fro. He said, “Then with the rains startin they aint ee-ven gowin send ol Jax back out. I’s gowin sit in that hootch all day with my water bowl an get fahhcked up. Let everythin pass til—WHAM! E-T-S.”

Morn’s early pallor penetrated the last light of the moon, permeated it, diluted it and finally diffused it until the moon disappeared. The fourth wave of Chinooks deposited Delta Company at LZ Sally. Warm sun assailed the ocher clay. The ground became warm then hot; the air lost its morning heaviness, the paddies their mist. The sun became blinding. In the ravines 246 boonierats huddled, covered their heads and eyes with towels or buried their faces beneath olive drab helmets still hoping time would pass without their having to endure its long uncomfortable minutes, its lagging dragging slow minutes, still waiting for the assault to begin. Slow minutes only a soldier knows. No, they are not like the minutes in a locker room before the big game nor like those backstage minutes before the opening night curtain rises. They are unique minutes. Soldier’s minutes. Boonierat minutes, undistinguishable minutes, undistinguishable millennia, unsavored, endured lonely minutes 13,000 miles from home. Once the assault begins the minutes will be different. They will be filled minutes. But these. These minutes. These. Perhaps the last minutes.

Above the first set of ravines the platoon sergeants of Alpha surveyed their men; Egan from the first; Pop Randalph from the second; Don White from the third. They spoke slowly and easily, the mark of old-timers. They laughed at each other’s quips and gestured toward the fuck-ups and laughed and cursed. The light skin of Egan’s face was already beginning to re-blister from the sun. Pop’s face, tanned deep red-brown with concentric creases surrounding watery red eyes, was dirt splotched where helicopter dust stuck to sweat. Don White, tall, wiry, coffee black, shrugged an unconcerned shoulder to the sun and lightly mocked Egan as Egan wiped salve on his lips.

“Mothafuckin cunt whore son of a bitch,” Egan mumbled scraping sand bits from sun blisters on his face and arms. “I hate these mothafuckin Shithooks and this fuckin REMF sun.”

Egan bent down and rifled through a sundry pak at his feet. The box contained candy and cigarettes, razor blades and shaving cream, toothpaste and brushes, writing paper, pencils and various odds and ends. The other sergeants picked through the box too. They left the box open for anyone who wanted to come up. Sporadically troops approached, took the candy and the cigarettes and returned to the ravines. Egan bent down and picked up a package of light blue stationery, then he rose, spat toward the trench and sauntered away. Fuck it, Mick, he said to himself. Drive on. His platoon was in order, had been in order for two hours. Echo Company still had not arrived.

Company commanders and operations officers and NCOs from Intelligence formed small groups on the landing strip. They had long since hashed and rehashed the operation schedules and objectives and now stood mostly silent, waiting to be under way. The sniper teams came in by Huey and reported to their assigned companies, dropped their rucks and regrouped on a small sharp ridge between the ravines of Alpha and Charlie companies. They too were mostly silent, smoking, checking their rifles and scopes.

The platoon leaders of Alpha joined Pop and Don White by the sundry box. All three were first lieutenants, young, in their early twenties, white, all-American ROTC officers. Two carried M-16s. Lt. Larry Caldwell carried a CAR-15. Pop sneered at him and the carbine and thought, that piece a shit. That weapon couldn’t hit a water-bo at two paces. Goddamn barrel’s too short, the buffer don’t sweep right and the damn thing jams evera other round. Wonder why Brooks lets Boy Asshole carry it.

In the trench below them one man finished reading a Fantastic Four comic book. He passed it to the man next to him who had been studying a worn skin magazine. That man passed his material to a man sitting up the ravine wall who had been reading a book on the religions of the people of Vietnam. The man on the ravine wall put the book down, glanced at the magazine, passed it on and returned to his book. The sitting and waiting became unbearable so men stood and waited. There was nothing else to do. It was impossible to rest anymore. Some men hunched over their rucksacks and adjusted the straps and ties and checked the pins on the grenades tied to the sides of the pack, tightening anything loose, checking the extra ammo to insure its easy accessibility. Other men cleaned their rifles, cleaned, polished, applied a light coat of LSA oil. It was the most repetitive action of the infantry, cleaning weapons. Soldiers disassembled their rifles, cleaned them, assembled them, checked them and then began again. Time passed.

Bellowing laughter exploded in a gully halfway down the landing strip, one very loud guffaw followed by secondary eruptions of giggles and chuckles. Men in other ravines stood and looked, strained their necks to see. Cherry climbed a step up the ravine wall to witness the joke. A smile came to his face. Yet the looking seemed to extinguish the joke and the gully quieted and the soldiers returned to their immediate worlds.

The restless infantrymen in the trenches and their clustered sergeants and lieutenants and captains on the landing strip represented a collective consciousness of America. These men, Chelini, Egan, Doc, Silvers, Brooks, all of them, were products of the Great American Experiment, black brown yellow white and red, children of the Melting Pot. Their actions were the blossoming of the past, blooming continuously from the humus of decayed antiquity, flowering from the stems of living yesterdays. What they had in common was the denominator of American society in the ’50s and ’60s, a television culture, the army experience—basic, AIT, RVN training, SERTS, the Oh-deuce and now the sitting, waiting in the trench at LZ Sally, I Corps, in the Republic of Vietnam.

A feeling of urgency, a contagious expectation swept over the men. The terrible enduring of minutes gave way to impetuous movement and thought, accelerating gradually, continuously, as lift-off time approached.

At the north end of the landing strip Egan sat alone, his legs dangling into a ravine. He was thinking of the World again, his non-Nam, pre-Nam World. I never did send her those sketches, he thought. He pictured the drawings of two homes that he had designed for a pre-architecture course. In their student days, his and Stephanie’s, he had sketched homes for her and she had designed interiors for him. In their heads they worked for each other yet they seldom actually sent the works to each other. Fuck it, Mick, Egan said to himself, I’ll bring them to her when I get back. He stared for a moment into the paddies before him then at the writing paper on his lap. He began a letter to Stephanie. He did not include date, time or salutation.

You are on my mind again. It is three years, maybe four now, since we lay on the freshly mowed lawn in the sun of mid-spring’s warmth. Maybe it is longer. Perhaps it is five years since we walked down darkened city streets in the quiet of pre-dawn or since we first sat on the floor in your room and listened to Sandy Bull’s Fantasia. I remember every moment, every word we said, everything we did. I do not know why my time here has not blunted my memory of you. Days with you stand out as if they were happening today, even with all that has happened between. I think I laughed a lot. You’d have to tell me for I don’t laugh like that anymore and it is possible I did not laugh then either but simply think I did when I think about you and me. I need to know if we ever really had what I sense we had or if it is just something in my mind now and it never was a reality.

When I was drafted—I wasn’t drafted. I enlisted. Did you know that? Was I that honest with you? I think you knew that whether I was honest or not. I have experienced it now, all and more than I wanted and I think now I could have stayed there with you and you would have been all the experience I’d ever have needed. But if I’d not gone I would have never known. Stephanie, we are starting a new operation this morning and I must get busy. I’ll continue this later.

Leon Silvers sat in a trench with Minh, Whiteboy and Doc. He also was restless. The others were fidgeting but not talking. Silvers opened his journal to make the day’s first entry.

Day 223—I look around me at my boonierat brothers and their sincerity amazes me. My own sincerity amazes me. I do not know if I am or am not my brother’s keeper or if I should be. I do not know if it is morally proper for my country to attempt to assist another to stop the infiltration from a third. I do not know if we should fight and spill our blood and have those we try to rescue spill theirs and again spill much of our enemy’s. Perhaps we should not. Perhaps we should not have gone to Korea either. Or to Europe for the First and Second World Wars. I don’t know if morality has anything to do with it, yet I look around and see these young men here about me. How can we feel this responsibility? Is that not morality?

All mankind is my brother.

Am I not my brother’s keeper?

If then, one of my brothers

Turns against another,

Am I not responsible to maintain

The latter’s keep?

All mankind is my brother.

I do not wish to side with one Brother against another.

I do not wish to have a brother

Against me.

But if all mankind is my brother

Mustn’t I be the keeper

Of my brother in need?

Why do some of my boonierat brothers think we should withdraw completely? Would we then not be like so many Jews in the 1930s allowing the world to push them around? I look about me and I know these men believe as I do, most of them at least, we must be here. If we were to leave, it would be immoral. Once we behave in an immoral way, we will lose our spirit and wander in the wilderness.

Silvers stopped writing. He looked around. It was very warm. There still was nothing to do. He removed a sheet of paper from the back of his journal and began a letter to his brother.

Friday, 13 August 70

Ab,

So your old lady wants you to marry her. No sweat, GI. Want me to discourage it? Can do. Can do it in a very tactful way. Tell her first you can’t wed til I get back, which really you can’t. I gotta be there. That’s about five months off and nobody gets married in January so you got it made at least til spring. I’ve got a year after I leave here and no telling where they’ll send me that I won’t be able to get back from so that puts it in winter again. Maybe what you should tell her is like this—tell her you want to get married in Europe while you’re racing formula 3 or 2 (if you can rob a bank). What could possibly sound more romantic than getting married in the pits at Monte Carlo just after your oil cooler’s sprung a leak and put you out of the race? The cars are still zinging by. You are covered with oil and depressed. Your bride is in a white leather suit of hot pants and vest (no bra) and boots. Just the sound of the whole thing will make your lady want to put the ceremony off til then. And that is, at least, a stay sent from the governor himself.

Now then, to the business at hand. What are the specs on the Hawke Super Vee? Is it a good car? Have you seen the new Lola and all the others? I find myself rather anxious over this buy. You salesmen can be sold anything. Are you going to drop down to 145 pounds? I’ve a feeling this could be a big year. I don’t mean big money-wise, but big for the breaks for the rest of your career.

I’m seriously thinking about joining Uncle Jake in business. He wrote to me with a real nice proposal saying he wants me to get my travel business license and open up an agency for him and me. I could really get into that, I think. I have got to have my own place or a place that is like half mine but where the other half doesn’t come around.

I’m going to enclose some notes on the Southeast Asia situation as I see it. Maybe you’d like to read them to some young ladies and then have them meet me at the airport with their panties at their knees. Two months to R&R. I’m going to fuck myself to death in Bangkok.

More later,

Leon

First Lieutenant Rufus Brooks sat alone on the edge of the landing strip, staring west. The heat of the sun was on his back and on the light black skin of his neck. He stared beyond his men’s restless shifting in the trenches, beyond the rice farms where peasants had appeared seemingly from nowhere, beyond the foothills with their clump greenbrown brush, staring at the mountains. Had there been a thousand more troops surround-ing him or none at all, it is inconceivable he would have noticed. I had her convinced that she was inadequate?! he thought. He sat still but in his mind his head shook woefully back and forth.

“Hey, L-T,” Egan said softly. He had come from the end of the strip where he’d been sitting, writing. Egan sat down beside Brooks. He looked toward the object of the L-T’s gaze. “What’s happenin?”

Rufus Brooks did not look at Egan. After a short silence he said, “I was just thinking about last night.” He did not want to mention his wife.

“Yeah,” Egan said. “That got to be a pretty heavy rap.”

“Yeah,” the lieutenant agreed. They were both silent for a moment. Brooks knew Egan had come to console him but he was not yet ready to talk about it with anyone. Brooks said, “Do you know what causes war?”

“Yeah,” Egan said relieved. He also was not yet ready to talk though he felt a duty to their friendship. “It’s when people shoot at each other over land. If they just do it, it’s a feud but if they got some crazy mothafucker leadin them, then it’s a war.”

“No,” the lieutenant said. “It’s how we think. People think themselves into wars.” He was happy to talk about war causation.

“I didn’t think me into this one,” Egan said.

“That’s not what I mean,” the lieutenant smiled though he was still looking at the mountains. “I was thinking mostly about cultural differences and how they affect our thought patterns and perceptions and actions.”

“Yeah,” Egan answered. “You can see it. I don’t know if I ever really thought a lot about it before.”

“You know, the causes of war are very deeply seated in white American culture and black America is being assimilated by that culture. This is an impossible war for black Americans to understand.”

“It aint too easy for whites either,” Egan said instinctively defending his race. They were silent again.

“What I mean,” Brooks said mildly, “is that the roots of war are in mankind, in each individual and the individual is manufactured by the traditions of his culture, A man is like a rough casting entering a machine shop. He’s already made but the culture he’s brought up in is going to sharpen his edges. That culture is going to re-form him, cut away at his humanity, mill him down to size and get rid of what the culture doesn’t think is necessary or efficient or beneficial.” Brooks was sounding like a professor again. “Traditional black culture,” he said, “cuts out the warcausing metal; traditional white culture accentuates it and sharpens it.”

“Hey,” Egan countered defensively, “you’re the L-T. You’re the boss man. You tell me.”

“Oh Danny, I don’t mean you and me specifically. I’m just talking. I want to think this out. If I go back to school, maybe I’ll write it all down. I kind of started on it last night. It doesn’t mean anything.”

“Fuck it, L-T. Don’t mean a fuckin thing. Now, what’s happenin? We goina get this clusterfuck in the air?”

“Yeah, soon. How’s your cherry doing?”

“I don’t know. He’s goina be okay. I’ll go talk to him. Get him psyched up.”

As Egan rose Sergeant First Class Jonnie Randalph came toward him and the lieutenant. Brooks continued sitting, staring to the west. Behind him Egan gestured to Randalph. Egan’s hand was at his own temple and his head was cocked toward Brooks, his hand twisted back and forth indicating that the L-T might have a screw loose.

“Mornin, Sir,” Randalph said as he sat next to the lieutenant. “Somebody said yer ol gal sent ya a Dear John. Thought I’d come by an cheer ya up some.”

Jonnie Randalph, platoon sergeant of the 2d Platoon, was at the midpoint of his third tour in Vietnam. He was thirty-six years old but looked sixty. He had been with the 7/402 on and off for fifteen years and had spent all his Vietnam time with the ‘SKYHAWKS’ battalion. In a society where the youngest man is eighteen and the mean age is twenty-one, a man of twenty-five seems old and a man over thirty is ancient. It was uncommon to find a man as old as Randalph humping a rucksack. The boonie-rats called him ‘Pop.’

“Pop, you old drunk,” the lieutenant smiled, “have you got your platoon all squared away?”

“Yea Sir. They been fine for a long time now so I thought I’d just come over heah and git ya fine too.”

“Thanks,” Brooks said laughing.

“Yea Sir. Happens to bout everabody. Happened ta me bout six weeks inta my first tour. Just bout the best thing evera did happen ta me.”

Brooks could not keep from chuckling as the small leathery old soldier slapped his knee, rolled his head around and chattered softly. “That gal a mine, why when I got back I looked at her and you know she’s got her legs crossed like this”—Pop flopped his right leg over his left—” like her cunt’s made a gold an I’m bout ta steal it. Well, Sir, we done it up right. There’s just one way ta do it, Sir. When you get back you an ye ol gal jump on one a them dee-vorce charters ta Alabam. Ya just go there with everabody else one weekend an they pro-nounce ya all dee-vorced. That’s what we done. Lordie! Then ya all come back on the same flight an ya all are a’ready dee-vorced so ya can party. Dang best ol party me an my ex eva went ta. Regular downhome orgy.”

The sun seared the staging area. Soldiers clustered. Leon Silvers, Doc, Minh and Whiteboy formed a closed foursome.

“Whut do you find ta write about au the time?” Whiteboy asked Silvers.

“Everything,” Leon said.

“Naw, Ah mean lahk whut?”

“Everything, Man. If you just let your mind use itself, you’d have hundreds of things to write about. I just write about what is or what I see and what I think.”

“You mean like you write bout this place all the time?” Doc asked.

“Shee-it,” Whiteboy laughed. “We aint done nothin in Ah doan know how long cept hump them fuckin-trails up en back. Up en down them fucken mountains. Humpin til one hill doan look no different from no othah hill en one NDP doan look no different from the las.”

“Whiteboy,” Silvers said, “just because there isn’t somebody there every minute to tell you how to think or what you’re seein doesn’t mean yer mind is supposed to stop. Look at this strip. We’ve never left on a operation like this one.”

“Yeah? Whut about Ripcord when we was gonna go in there en bail em out?”

“Damn,” Silvers said. “You remember that mothafucker?”

“Yeah,” Doc said. “We was gettin the word second-hand all the time. Man, dint nobody know what the fuck was happenin.”

“Yeah,” Whiteboy said. “Ah remember they sayin theah was fifteen dink reg’ments out theah. They was s’pose to be like ants movin up the side a the hill. They was losin whole comp’nies.”

“That is the way it was,” Minh entered the conversation. “I talked with a scout who was there. They had human wave attacks.”

“Yeah,” Doc concurred. “They say when the last bird was leavin that sucka the dinks was on top throwin smoke grenades tryin ta get the birds back in. That sucka was completely overrun, Mista. OVERRUN.”

“They lost some artillery tubes up theah and Ah heard the gooks got em.”

They were speaking to pass the time, entertaining each other with old tales. Chelini could hear the discussion. He wanted to be part of it but he did not know how to get their attention. He listened for an opening.

“They spiked them tubes with thermite grenades,” Silvers said authoritatively.

“Yeah,” Whiteboy agreed. “But they dint destroy em all. Ah heard the gooks got some of em off the top.”

“No,” Silvers insisted. “They brought in the fast movers and bombed the entire hill and destroyed everything. Shee-it. Remember those days when it was bein overrun. It was supposed to be any minute and we were goin out.”

Doc said emphatically, “We sat there fo three days. Three days, Mista.”

“Yeah. Shee-it.”

“When they give each a us a plastic bag a plasma Ah near shit mah pants. Ah was so scared sittin theah Ah was shakin lahk a leaf in a twister.”

“Man, when they finally told us Ripcord’d been overrun I was one fully relieved mother. I think I wrote a dozen letters in those three days.”

“Ah’ll tell you, that was the only time Ah ever heard a the 101st losin men. But Ah wasn’t gonna write home about it. The way Ah heard it, theah was wounded left behind.”

“Yeah,” Silvers said. “That’s somethin that should be written about. Man, I just write notes to myself so I’ll remember what this place was really like. I don’t want to be spreadin any bullshit when I return. That’s the whole trouble with this war. Everybody’s tellin war stories and nobody’s tellin it the way it is.” Silvers paused. He turned to Minh. “Hey, Minh, what’s the word you got about where we’re goin?”

“I think I only know what you already know,” Minh said.

“Come on, Fucka,” said Whiteboy. “What do the othah scouts say about wheah we goan?”

“They say it is a bad AO. But you have already heard that.”

Until 1968 Le Huu Minh had never supported any of the numerous governments of South Vietnam. He had not supported the communist National Liberation Front or the North Vietnamese infiltrators or the American presence in his country. Until 1968 he had been an anarchist. Like many of the young men from the city of Hue and the surrounding province of Thua Thien, Minh was highly educated and believed strongly in the autonomy of his region. As a student he was fond of quoting the ancient Vietnamese saying, “The authority of the government stops at the hamlet gate.” To Minh that saying had many facets. A national government had authority only down to the province, a province government only to district, district only to hamlet and hamlet only to the doors of a man’s home. No one had the right to intrude upon a family and no member of a family had the right to intrude into the thoughts of an individual. That was the natural course of the universe.

Minh had been born in the village of Phu Thu, twelve kilometers south of Hue. Like most peasant boys he worked in the rice paddies from the age of four and by six he was responsible for his family’s two water buffalo.

In 1958 most schools in South Vietnam were still segregated between Europeans and Asians, a vestige of colonial days. For Europeans education was universal, for Vietnamese it was nearly universally prohibited. Unlike most of the boys of his village who never received any formal schooling until conscription forced them into military training, Minh, at ten, was enrolled into the French-built Catholic school in Phu Luong. At fourteen Minh left his family and entered Quoc Hoc High School in Hue, the same school that had been attended by Ngo Dinh Diem, Ho Chi Minh, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap. In 1966 Minh became a student at the University of Hue, one of three universities in South Vietnam. The school had five colleges—Law, Medicine, Letters, Science and Pedagogy—scattered throughout the city, and it served some 3000 students. Minh was enrolled in the School of Letters, a very big step for a peasant boy.

Hue University was the Berkeley of Vietnam, a center of political activism and controversy, a haven for Vietnamese draft dodgers and a source of falsified identifications. As long as a male had identification proving he had not yet reached his eighteenth birthday, the military would not, could not draft him. At the university there were men who had been seventeen years old for years.

Hue itself was a beautiful city and the most independent city in all of Vietnam, North or South. The old Imperial City with its Palace of Perfect Peace, its villas and gardens, temples and ancient palaces, embodied the glory and traditions of the past. Wide boulevards paralleled the beautiful parks along the River of Perfumes, an ancient name derived from the choking lotus that thrived in the deep meandering waters. Old French Citroens rolled past tile roofed houses inside and about the Citadel and past the long villages of sampans floating in the sweet smell of the river.

Hue was established in 1687 by Nguyen dynasty warlords, who built two great walls stretching from the sea to the mountains designed to help them defend the South from the Trinh warlords of the North. The walls were built just north of the present DMZ, a line that had traditionally divided the countries. In the late 1700s Quang Trung, who united all of Vietnam and drove the Chinese out of Hanoi and the North, proclaimed himself emperor and ruled from Hue. The city became the national capital. In 1802 Gia Long captured Hue with French assistance and he re-established the Nguyen dynasty which lasted for 81 years. Under Gia Long the impressive, nearly impregnable Imperial City, the multi-walled Citadel, was constructed. In 1883 the French bombarded the Citadel and captured the royal court. From then until 1939 Vietnam was ostensibly ruled from Hue by emperors condoned by the French colonialists and then until 1945 by emperors condoned by the French, who were in turn controlled by the Japanese. In August 1945 the last Vietnamese emperor, Bao Dai, renounced his throne to the Viet Minh revolutionaries. The French returned only to be ejected in 1954. Over the next six years lines were re-drawn for the North-South conflict.

No longer a national capital, Hue became the scene and center of dissent, the heart of the 1963 Buddhist uprising against the Catholic regime in Saigon and the center of the Vietnamese intelligentsia. The spirit of Giai Phong, liberation and independence, increased and fostered numerous political factions. It was to one of these factions Le Huu Minh attached himself and developed his own strong political beliefs and it was with this splinter group that in the fall of 1967 Minh joined the alliance of the Right Bank Resistance. As he plotted for the general offensive and uprising that would liberate Hue from the oligarchy of Americans and Catholics and the Saigon puppets, Minh never thought that a replacement machine of northerners might be both more repressive and more exploitative. It never occurred to him that the northern political machine might fully replace the current regime and exclude his faction. As a member of a splinter group Minh knew little of the plans for the offensive, but as an activist he was able to state the needs and reasonings behind it. The TET Offensive against the city of Hue, against his city, by the NVA 800th, 802d and 804th Battalions began his cruel awakening to the realities of power.

Chaos, that most wonderful word to an anarchist, became terror. The NVA and Viet Cong, in control of the Right Bank from early morning 31 January 1968, systematically hunted down and executed an unexpectedly long list of targeted people, a list that included apolitical doctors and missionaries, Buddhists, Catholics, university professors and students. By the end of the first week of the Year Of The Monkey Le Huu Minh found himself sheltering enemies of the people. The city was in shambles. Virtually every building south of the river had been smashed jagged by mortars or rockets from the opposing armies. Triangulated steel truss bridges over the River of Perfumes lay twisted as if they had been constructed of rice paper and bamboo. Behind the heavy walls of the Citadel the fighting raged. Minh was exhausted, nauseous, for weeks. The land and city he loved had been devastated.

In July of ’68 Minh hoi chanh-ed to an American MP. He was interrogated and released. Peace had returned to the lowlands and American memories are very short. But peace was not in Minh. He convicted himself of war crimes. Again Minh gave himself to an American MP and again he was interrogated. He pleaded to become a scout and was finally accepted into the Loc Luong 66 program, a program for ex-VC and ex-NVA who had ‘rallied’ to the GVN.

Minh was shipped to Saigon for indoctrination and then to Tam Ky for training. From Tam Ky Minh was assigned to the 10lst where he underwent additional indoctrination at Camp Eagle. Minh was shipped to Camp Evans, buddied-up with an American line unit soldier and “oriented” for eight more days. Finally Minh and his buddy went through the standard SERTS training. Upon completion of the program Minh was assigned to the unit of his buddy, to the Reconnaissance Platoon of Company E, 7/402, as a Kit Carson Scout. As his ability to speak English improved he moved up to better jobs, first to S-5, Civil Affairs, where he worked as interpreter for MEDCAPs and then to Senior Scout for Headquarters Company. With the arrival of higher ranking Vietnamese soldiers Minh was demoted and became the scout for Company A.

The perpetual smile on Minh’s face angered Whiteboy. “Damn gook a’ways laughing at us,” he would say when Minh was not around. Minh was a foreigner; he could never be part of Whiteboy’s Alpha Company. “Minh, you lit’le fucka,” Whiteboy said, “the Jew asked you a civil question. Why doan you give him a straight answer?”

“Whatcha gettin on his case fo?” Doc said. “He tellin ya it’s goan be a bad mothafucka. Goan be another 714. Huh, Minh?”

“I do not know,” Minh said still smiling. “I hope it will not be so.”

“Fuckin ay, dammit, best not be,” Whiteboy snapped. “Ah’ve ordered me a Super Sport ta hop up when Ah get back home an Ah sures hell expect ta be theah when it arrives.”

Minh continued to smile. The muscles of his face ached from smiling but it was his only response to the Americanisms which he did not understand. Later, if he was alone with Doc or possibly El Paso, or if he were in the rear with Lamonte, he would ask questions and he was often surprised to find that many of the American soldiers had as little understanding as he of 427s or 352s or Holly four-barrels which were not weapons. Minh had often been surprised and pleased to find that Americans smiled outsider smiles just as he.

But with Minh it was that way more often than not. The creases from the constant smile on his face became deep and permanent. The Americans looked at the dumb smile and they saw the misunderstanding in him and they saw their own lack of knowledge of Americana and they hated him because of it. Minh knew he was an outsider and this scared him when he was in the boonies. He feared that if Alpha got in trouble, became pinned down in contact, the Americans would not jeopardize their lives to save his. Minh was thus overly cautious and the American soldiers thought him a coward. In turn Minh hated most of the Americans he served. There were individuals, El Paso and the L-T and Doc, whom he developed genuine friendships with, symbiotic intellectual relationships, exchanging and defining against each other their cultural heritage and in that, themselves.

In his village and among his city friends Minh was also an outcast. To them he had become Americanized. The riches of the wealthiest land on earth were at his disposal. He was a farmer milking the great cow, prostituting himself and his country for material benefits. Minh was a man alone with broken ties to his culture and with shallow ties to the American military presence.

“Hey,” Silvers said, “you know what I was just remembering?”

“Yeah,” Doc laughed. “I’m inside your head.”

“I was remembering when I first came in-country,” Silvers said laughing along with Doc. “I remember we had just gone through in-country training and, ah, everybody was still scared. There was so much that was unknown.”

“Damn”—Whiteboy drew the word out for extended emphasis—” that so far back, Ah can’t recollect none a it.”

“I remember it very clearly.” Silvers gazed into the ground then looked up. “Or at least this part. I remember we didn’t know where we were going or what it was goina be like. During training we kept hearing about this one battalion that had been mauled really badly and we still hadn’t gotten our assignments as to where we were goin. I remember goin into the EM club there and getting a beer. I had just gotten assigned to Alpha Company, 7th of the Four-oh-deuce. And the guy says to me, ‘Where you going?’ I said, ‘Alpha Company, 7th a the Four-oh-deuce.’ And he says, ‘Here.’ He says, ‘Here. The beer’s on the house.’ This cold chill ran up and down my spine. I thought, ‘Oh God, it’s all over. The minute this guy hears where I’m goin he gives me a free beer.’”

Doc and Minh laughed and Whiteboy said, “You really remember au a that? Ah doan know. Ah got two mo months then Ah’m gettin out.”

“What you goan do?” Doc fed Whiteboy the question.

“Ah’m gonna do, Ah guess, just lahk ma daddy did. Think Ah’ll get on with the railroad. Ah’m sure my daddy can get me on as a brakeman or sompthin. Ah got a letter from a friend the othah day and he says mah ol sweetheart’s had a kid an looks lahk a Sherman tank. Ah guess Ah’ll just drift a bit then get on with the railroad but Ah doan really know.”

“What about you, Doc?” Silvers asked. “What are you goina do?”

“Too early ta say yet,” Doc dodged the question. He would like to have said he was going to continue his education in medicine, become a nurse or a technician or even a doctor, but he believed those things were beyond the hopes of a poor Harlem black. “I think I’ll jus get out first,” he said. “What bout you, Minh? We know the Jew goan buy a respectable whorehouse but what yo gonna do? You in fo the duration.”

“To me,” Minh said, “it is most important for peace to return to my country and for all of you to go home. We do not have futures as long as the war continues and as long as your army is in my country.”

“God A’mighty,” Whiteboy snapped. “We’re heah bustin our guts out for you lit’le fuckers and au you can think of is throwin us out.”

“Why you gettin on his case again?” Doc said. “If I said to you it’s time yo left yo’d say ‘Right On!’ and thank me. Shee-it. Minh, I say thanks fo wishin me the fuck out.”

“Ah, fuck this shit,” Whiteboy said and strode up the ravine.

Whiteboy moved his great bulk smoothly, stepping lightly over Jackson and around other soldiers, over Cherry and up the loose gravel incline onto the landing strip. Cherry had been following their conversation on and off and as Whiteboy stepped over him he smiled trying to indicate to Whiteboy his own approval of the big soldier’s position. Whiteboy did not acknowledge him and as he passed Cherry thought, that guy, he shouldn’t treat Minh like that. Whiteboy proceeded past the lieutenants and the sergeants to the devastated sundry pak where he grabbed a new deck of playing cards. Whiteboy nodded to Pop who was standing with Don White guarding the remaining supplies. The big soldier flexed his muscles, squinted up and down the strip and returned to the ravine.

All the men in the ravines were sweating. The sun had turned the small canyons into ovens. The men chatted blindly. Some men opened canned C-ration fruit. Others munched candy bars. They shared the fruit and candy, sometimes passing food between groups.

Whiteboy sat again with Silvers, Doc and Minh. He broke the seal on the deck of cards, removed the jokers and began to shuffle.

The last wave of Chinooks approached. Whiteboy held the cards tight. Troops turned their backs to the storm of the descending helicopters, a shower of loose landing strip pelted their worn fatigues even though the CH-47s set down at the far end of the strip. Echo Company and the scout dog teams disembarked. The big birds lifted, climbed, swung toward the sea and were gone.

Jax got up from near the card game, walked up the ravine to the sundry paks, removed a can of shaving cream, shook it up then artfully designed a large elliptical peace symbol on the hot hard ground. El Paso came up behind Jax, looked at the peace symbol, tapped Jax on the shoulder and said, “Never happen.”

“Na, Dude,” Jax responded, “doan be a fool. Yo gowin be outa here and I gowin be outa here before it happen but I bet ten ta one Cherry doan pull no full tour.”

In the trench sitting back against his ruck, sitting beside Jax’ ruck, Cherry scratched sand from his scalp. Dust and grit stuck to his sweating arms and neck. He was miserable. He was still alone.

The staging area was now a cluster of hundreds of individual activities. Cherry was surprised, as he looked up and down the strip, to see so many men. In a ravine behind him a platoon sergeant snapped at the troops from Charlie company. “Come on,” the voice demanded. “Turn in all your pot. Let’s go. Pot, pills, hash. All that shit. Come on now, I know you got that shit. I’m going to go for a walk. Go up and throw it in the sundry box. No questions asked. If you don’t turn that shit in, I’m going to find it on you. If I find it in the boonies, yer goina be in a world a hurt.”

“Shee-it, Egan,” a voice boomed out. “I don’t know how you kin smoke them gook cigarettes. They smell like they come outa the asshole of a dyin gook whore.”

Egan was coming down the ravine. Cherry did not look up though he followed Egan’s approach with his peripheral vision. Egan was looking directly at him. For the first time Cherry really noted Egan’s physical appearance, noted the ill-fitting faded and torn fatigues draped over the wiry thin body, the dilapidated jungle boots worn bare of color, the jungle sores and sun blisters and scars on Egan’s face and arms.

Egan squatted beside Cherry and in a voice coming from low in his throat he said, “Aint this a fucker?”

“This? What?”

“This,” Egan said looking Cherry up and down and then straight in the eyes. “You doin okay?” he demanded.

“Yes.”

“Aint this a bitch though?”

“What?”

“This havin ta go look for em,” Egan said teasing Cherry with the half statement. He spoke at Cherry, aimed his voice at Cherry’s face. “My bag is killin gooks,” Egan said. “I really love it. Didn’t I tell you that last night?”

“Ah … no …” Cherry stammered.

“I remember the good ol days,” Egan said. His eyes shone. “Tet a ’69. It was tremendous. We had gooks runnin around the battalion AO. Right in Eagle. Man, they’d gotten through the perimeter. This is a fucker but back then you didn’t even have ta go lookin for em. Shee-it. Now you don’t find enough ta fill an ant’s asshole. But before—you could just walk out in back a the orderly room and shoot a few.”

Cherry stared at Egan. Egan was glaring him in the face. Cherry looked away, frightened. My God, he thought, this character’s sick. Cherry looked down at his knees. He still wore one of the uniforms he had been issued at Fort Lewis. It struck him how new his fatigues were. He looked up at Egan then past Egan and he realized that he, of all the men in the ravine, had on the only new uniform. His skin was the only clean skin, the only skin without sores and scabs and bandages.

Egan’s voice rose in an eerie whisper. “Maybe we’ll get ta shoot some gooks today—shoot em right through the fuckin head. Would ya like that? DAMN! War is good. Really good. You love it, don’tcha? Don’tcha?” Egan leaned forward pressing Cherry for affirmation.

Cherry trembled imperceptibly. “War,” Egan said forming his lips into a trumpet and sensuously blowing the word at Cherry. “They send you to the far corners of the earth. You hear the blasts of artillery and bombs. You get weapons, helicopters. You can call all heaven down, all hell up, with your radio. War. It’s wonderful. It don’t make a gnat’s ass difference who the enemy is. Every man, once in his life, should go to WAR.” Egan harshly flicked the butt of his cigarette across the ravine then spat into the earth between himself and Cherry.

Cherry hesitated, then muttered, “Yeah, but is it right?”

“Winning makes it right,” Egan snarled. “You can count your cherry ass on that.”

“What about the corruption?” Cherry asked more aggressively.

Egan snapped harsher, “Corruption?! What corruption? Thieu? Are you goina tell me if the gooks win, they won’t be corrupt? Do you think they’ll be better? Do you think their honchos won’t rape and pillage? You can kiss my ass. You’re missin the point. Fuck the honchos. It’s us or them. WAR! May the best man win. WAR. Beautiful WAR. When yer kids ask ya, ‘Daddy, who’d the night belong to? Daddy, did you kill anybody?’ tell em the night belonged to Egan—and he killed everybody.”

Egan stomped away. Cherry did not look at the men about him. He was sure everyone was staring at him. He breathed deeply trying to gain control. Things had been coming together slowly for him. At first everything seemed detached from every other thing; each incident, meeting, conversation seemed to be a separate entity. Then things began to blur; one incident became indistinguishable from another, the starting and stopping in time and physical arrangement became all screwed up in his mind. Egan’s tirade had suddenly caused a connection, a clear slash of reality through the haze. It was the beginning of understanding, the beginning of Cherry’s loss of innocence. Chelini was at war. “You are finally goina see it,” he mumbled to himself. “You’re finally goina be a part of it.”

Off the landing strip at the beginning of a tiny divide between two ravines of Alpha Company troops, Lieutenant Brooks re-briefed his platoon leaders, forward observer and two platoon sergeants. In one hand he held a map of the operational area, in the other his M-16 rifle. “Birds will be here in one-three,” he said. “They’ll land at thirty-second intervals. We’re going up in platoon order, first, second and third. Have your men arranged in pick-up order. Where’s Egan?”

“I think he went off to write a letter to his lady,” Lieutenant Thomaston said.

“Tell him to get moving. Okay, let’s break it up. Have em get em on.”

Lieutenants Caldwell and De Barti walked off with their platoon sergeants. Lieutenant Thomaston strode over toward where Egan stood cussing.

Seven men approached Brooks from the center of the landing strip. They were dressed in smartly tailored, well-starched fatigue uniforms. Leading the group was the 3d Brigade commander. He wore a spotless helmet with a freshly starched cloth helmet cover. On the front of the cover were embroidered gold letters spelling out OLD FOX in a horseshoe wreath. Inside the wreath was the silver eagle insignia of his rank.

By the side of the Old Fox was Lt.Col. Henderson, the GreenMan. Both men wore web gear over their fatigues and both carried .45 caliber pistols in polished leather holsters. Their boots were so shined that somehow the dust of the strip had not dulled or coated them.

Behind Henderson was his aide and behind the Old Fox was his entourage of aides and advisers. The commanders approached Brooks together while the aides hung back a respectful three or four feet.

“Good morning, Sir,” Lieutenant Brooks saluted.

“Good morning, Lieutenant,” the two senior officers saluted in unison.

“Lieutenant Brooks, I do not think I have had the pleasure of your acquaintance before but I’ve heard nothing but positive reports about you for the past week. I’d like to say it is an honor to have you in my command.”

“Thank you, Sir,” Brooks replied uneasily.

The Old Fox spoke perfectly, weighing each word for effect and calculating the response each received. “Brooks, I am the Colonel, The Man, The Old Man if you like. And what I say goes.”

“Yes Sir.”

“Lieutenant, if there is one thing life has taught me it is this: You have to pay for what you get. Don’t you agree?”

“Yes Sir.”

“You have to pay for liberty, for freedom, for justice.”

Christ, Brooks thought. What am I in for now?

“I want to tell you something about war, about this war. I want to impart to you lessons I’ve learned that seem to be lost on our youth today. I’d be very pleased, Lieutenant, if you’d impart this lesson to your platoon leaders and NCOs. I’d’ be very pleased if my words filtered down to your brave men. How old are you, Lieutenant?”

“Twenty-four, Sir.”

“Twenty-four,” the Old Fox repeated quietly, shaking his head. “Lieutenant,” he said louder, “this infiltration is like a cancer to this nation. It’s like a tumor which we’ve attacked. We’ve halted its growth and possibly reversed its gnawing, rotting progress. When Marines first landed in I Corps back in ’65 most of their contacts were made within five to eight kilometers of the cities. In ’67 and ’68, with the exception of the Tet Offensive and Counter-Offensive, the fighting had moved into the jungles and away from the populated lowlands. Now, Lieutenant, we are in the mountains thirty, forty, fifty kilometers from the cities we must defend. A lot of Americans have paid dearly for this protection and we have been paid back. We have checked this cancer. But until the victim is strong enough to combat this disease by himself, our aid is paramount to his survival.”

“Yes Sir.”

“One of our problems is public opinion, Brooks, and you and your men are part of the public. That’s why I want to address you personally. The North has never publicly admitted either to infiltrating the South or to its ultimate objective of conquering the South. That lack of a clearly stated objective has tricked many Americans into questioning whether their objectives, so fully exposed by our intelligence network, are indeed real. Many Americans simply do not believe it or choose not to believe it yet we are about to tangle with a massive element of NVA regulars—infiltrators.

“The purpose of our being here is to defend South Vietnam, not to occupy or to dominate it. We are an army opposing an army. They are an army who has come to conquer. We may well try to capture or control the same objectives but our intent is not identical. We are defenders, not aggressors. As President Johnson once said, ‘Aggression unchallenged is aggression unleashed.’ We are here to challenge the aggression from the North. Do you believe that, Lieutenant?”

“Yes Sir.”

“Good, Lieutenant, because if you believe in what you are fighting for, if you support the cause, you are more apt to be willing to die for that cause. If you do not believe in what you are fighting for, you fight badly. If you fight badly, you are more apt to lose and more apt to die. It is a paradox of traditional warfare that if you believe in the cause for which you fight, you are more apt to risk your life, more apt to win, less apt to fight badly and less apt to die. More risk but less death. That, Lieutenant, is why you and your men must believe in what we are doing.

“We are the strongest, toughest, hardest fighting division in the Army. But by the news releases that I see every day, one would think we are a bunch of pansies. Lieutenant, I believe in our just cause and I want you to know you are backed by our every asset. Either we shall all pull together, fight together or we shall die together. That’s the way it is. Lastly, Lieutenant, you would not be here, your men would not be here, if your country did not need you. Believe me, Lieutenant, your country will repay you many fold.”

The Old Fox saluted Lieutenant Brooks, awaited a return salute, executed an about-face and marched toward the commander of Charlie Company. Colonel Henderson waited until the brigade commander was a dozen paces off then said smiling, “Rufus, that man’s on our side and I’m sure he likes you. You might get a personal letter of recommendation from him for your file. Now I’ve got several operational changes for you and clarification and delineation of objectives. May I see your map?”

In the corner of his vision Brooks watched the Old Fox and his entourage as they approached then encircled the commander of Charlie Company. He lifted his map for the GreenMan with detachment, momentarily concentrating on the Old Fox.

“Rufus, you’ll CA to 848 as planned,” the GreenMan spoke excitedly. “You’ll work west across the ridgeline and north down this finger and then onto the valley floor here and then work toward this knoll as best you see fit.” The GreenMan pointed to the center of the valley on the map where brown concentric circles indicated an elevation rise. He studied the map as if he were planning the operation for the first time, directing attention to topographic details with his stubby clean fingers. “This knoll is your ultimate objective. I see it taking ten to twelve days to clear this AO.

“There’s a strong enemy force in this valley. We’ve added a reinforced company from 3d of the 187th to secure Firebase Barnett and this is going to give us two additional maneuver elements. As you know Bravo Company is going to assault here, northwest of you. They’ll set up a blocking force on the northeastern end of the valley. Charlie Company will not secure the firebase. Instead they’ll be inserted here to the west and secure that flank against any additional enemy units coming up the valley and block any units trying to escape. Delta Company will go in here and set up a blocking force on the north escarpment and check out the caves. Recon will be inserted directly behind you, here. They’ll follow you by a day or two until they reach this point on the south ridge where they’ll close off any NVA travel between this valley and the O’Reilly area. Each of the blocking forces will search their areas for bunker complexes and enemy concentrations. But you, Rufus. You’re going to be the rover.

“I want you and your men to check out the valley floor and to work toward this knoll. Have you got that?”

“Yes Sir.”

“Rufus, I’m looking for a fight,” the GreenMan said exuding enthusiasm. He boasted, “We are hos-tile, a-gile, and air-mobile. I don’t know how much of a cancer these NVA are. I don’t pretend to know what the political picture is. But what I do know, Rufus, is how to fight. I know how to find and defeat the enemy and how to do it with the least casualties. I promise you the utmost support. I know what you’ve accomplished in these mountains and I know the sacrifices you and your men have made. You are a natural born soldier, Rufus. A real jungle man. Your sacrifice has bought time for the people of our area, from, Quang Tri to Hue and all the way south, and it has brought peace to this population. We can’t fail them now. We don’t allow failure.”

Brooks kept his face down to the map while Henderson spoke. He’s like a chubby little kid, Brooks thought. Like a little kid playing with tin soldiers on a dirt mound in his backyard in the middle of Missouri or some place. He’s having a good time now. That’s cool. It’s partly because he plays so well that we’re good. Because we’re good our opponents cut us some slack. It makes it easier.

“Rufus,” the GreenMan continued, “you are a thinking human being. Your men are intelligent and experienced. I’m not going to send in a lot of plays from the sidelines. You be your own quarterback. And Lieutenant, we are playing for keeps. I know you know that. This is the big game, Rufus.” The GreenMan checked his watch. “The Air Force has prepped ten landing zones. We’ll use five; five are diversionary. You’ve got a good company, Rufus, a goddamned fine company. Best in the battalion, in my opinion. Maybe best in the whole goddamned division.”

“That’s a real honor for a first lieutenant. If things work out well we’ll see that you get that promotion to captain. Who knows, maybe we’ll get you a Silver Star. That always looks good on a young officer’s record.”

“We’re ready. Sir,” the colonel’s aide interrupted. “The birds are due here in zero-three.”

“Thank you.” The GreenMan paused and looked Brooks coldly in the eye. “Best get your men lined up,” he said, his chin tight and hard. Then he saluted Rufus Brooks and said, “For the Glory of the Infantry, Lieutenant.”