CHAPTER 25

18 AUGUST 1970

First light broke upon the valley as ugly gray mist. The drizzle had not ceased during the night. Alpha was awakened by a horrible roar as if they lay beneath a speeding freight train, then a boom, then the explosion. Jax jolted up. It was still dark on the ground. The top of the grass was just distinguishable from the moist sky. SSSSSEEEECKK-boom-BOOOOMM split the air above him. “Motha! They firin dat thing too mothafucken close.” The roar split the sky again. “Shee-it.” Jax lay back down and tried to sleep. Another round passed over. An eight-inch howitzer from Firebase Jack far to the south had begun the road mission. Alpha was on the GTL, gun-target line, a straight line from the gun to the target. They heard two explosions for each projectile, the small sonic boom of the shell traveling faster than the speed of sound, then the explosion of the round. As each round passed over Jax could feel his back trying to grab the ground, trying to mix his molecules with those of the dirt. The howitzer fired twelve rounds over a half-hour period and then ceased.

Jax pulled his poncho and poncho liner tighter over his head. The drizzle became rain. Grayness penetrated into the grass. A single large drop of water worked its way under Jax’ poncho and onto the skin of his back. A chill ran up his neck and down his arms and legs to his fingers and toes. Quietly Jax rolled over and went back to sleep. A minute later another drop squeezed past the poncho and fell into his ear.

“Okay, okay,” he muttered. “I’s gettin up.” Jax threw off his poncho. His fatigues were soggy and his skin felt as gray as the sky. Jax removed packets of cocoa, sugar and cream, and a piece of C-4 from his ruck. He grasped his canteen cup which had filled with clean rainwater during the night and put it on his C-rat can stove. He lit the C-4, it flared white hot and died out. The water boiled. Jax mixed the packets and sipped the steaming brew. His breath formed a cloud before him as he blew the cocoa to cool it. Around him no one else was stirring. Jax scrounged in his ruck for a clean pair of socks and the foot powder Doc had given him. He sat down and removed his boots and socks. The skin of his feet was clammy gray and swollen. The constant moisture was causing the surface tissue to peel. Jax looked at his feet for a moment then said, “Hello, feet. Remember me? I’s the dude got yo dowin all the dancin. I jest want ta let yo know Jax ree-lee a-preciates the job yo ol boys down der dowin fo me up here. Guess whut? I brought yo somethin. Got yo dudes some powder an a pair a socks that like new. There”—Jax sprinkled the powder on his feet and rubbed it in—” how dat feel? Fix yo dudes right up. Yo jest take it easy now. Yo hear da news? Yo pappy’s a squad leader. How bout dat? Hey, hey. L-T say we gowin sit here today. Gowin take it easy. First thing I gowin do, feet, is get yo back in yo stinkin home. Then we gowin clear this AO a leeches, then we gowin rest.”

The fog cloak over the valley floor rose with the dawn. It now lay ten to twelve feet above Alpha. Visibility below the fog would have been perhaps an eighth mile had the thick grass permitted it. Boonierats woke cautiously, quietly. Egan was up, sitting on his ruck, writing. Cherry was awake though he had not yet moved. He looked at Egan. Egan’s face was swollen and his right eye was swollen half-shut from the leech bite. Cherry lay motionless. It had not been a good night. He had lain awake long after the conversation had ceased and when he did finally sleep, he dreamed.

Cherry had had first radio watch. During the watch he had thought about Silvers, about how he died. He analyzed every detail and he thought about alternative ways to carry his radio so it would not announce to snipers or trail watchers his important communication function. During his vigil he did not close his eyes. He lay back. His body tense. It was as if all his nerves were one long thin filament stretched taut. And it was in motion, vibrating, like a piano wire. It was as if someone had started a wave action in the wire and the waves oscillated and moved up the wire quickly, hit the end and bounded back through new waves zinging up. He had lain there jangled and taut, not in fear of death or of being hit, but in fear of not acting, not knowing how to act. His face burned as if all his energies were being forced into his head.

Cherry reviewed everything he could recall about jungle warfare. He recalled basic training and AIT, RVN training and SERTS. There had been night-fire classes, quick-fire drills, first aid and ambush classes. Cherry wanted to be good, had to be good, he decided, if he was to survive. In his mind he rehearsed what he should do if he were in column and they were ambushed from the left. He imagined his body reacting left. Then to the right. Front, rear. If someone near him were hit he placed himself mentally in the situation. Then he thought about calling in artillery support. He could do it—if he had to. Of that he was certain. He said to himself, if you think about a situation happening and you think about the proper response, when it happens you will respond properly without having to think. What did Silvers do? How does El Paso sound? Egan. How does Egan move so quietly? What does he do? How does he look? see? smell? feel? Cherry tried to assimilate all their lessons.

Then Cherry had passed the radio to Egan and had lain back and closed his eyes. A picture of Leon Silvers burned on his mind. Wrapped about Cherry, his water-soaked poncho liner became a blanket of sticky warm blood. He opened his eyes. He thought of turning to Egan, of offering to allow Egan to sleep while he took another watch. He decided against it. When the single shot felled Leon on the road Cherry had not jumped from the noise. His mind had been wandering and though the AK pop had startled him, it was the sight of others diving into the grass which brought the awareness of danger to him. I was probably the last fuckin guy off the road, he said to himself.

Cherry quivered. His insides pounded hot, pulsed painfully. His brain ached. He could barely breathe. He forced himself to allow the nightmare to begin. He forced himself to observe his mind in terror.

Half of him was on the enemy road. Everybody had scattered. Leon lay crumpled in a massive bloody heap at Cherry’s feet. The sweet smell of blood rushed to Cherry’s nose. The image was entirely still except for Cherry’s own motion as if Cherry stood in a color photograph. He screamed. “That bullet. That was mine. That was meant for me. For my neck.”

From out of the trail, rising ghost-like from the earth, through the vehicle marred road, rose a figure. The figure wavered as though seen through heat. It was dressed in US jungle fatigues and it was soaked in blood. The image of Cherry’s body beneath its ruck shook. Its chest tightened as Cherry’s chest tightened on the ground where he lay. Breathing became difficult. Cherry allowed the image to run. He realized he had control over it, could stop it now, whenever he wished. He watched his image watch the horror of the sordid scene on the road. In the photo Cherry froze now as the figure on the trail continued to rise and once at full height the rippling mirage solidified. It was that face again, a firm face, tight yellow-tan skin stretched over delicate bones, deep brown eyes laughing. The figure took one step forward and the face burst in deep red gush splatter. Cherry laughed.

The picture shifted. It came alive. The bloody Silvers at Cherry’s feet became an angered, wounded, filthy rat clawing toward the grass shrieking and dragging its shattered gory abdomen. In the grass a hundred foul creatures scurried aimlessly in interlocking circles. Then the ghost figure before Cherry dropped. The head became a skull and glowed iridescent green. It approached. It came closer. It became larger and larger and winds swirled about the green glow until they whisked Cherry’s weapon from his hand and blew his helmet from his head. Cherry spun and fled and laughed madly. He ran with every atom of energy in his being. The glowing skull became larger. The frozen wind lashed at Cherry’s back. “You’re not God,” Cherry’s image teased, tormented the spirit. “You’re not God. You’re Satan. Fuck you. You can’t touch me. I’m God.”

“Hey,” Egan woke Cherry. “What the fuck you laughing at?”

Cherry did not fall back to sleep or to dream. He thought about Leon. Hadn’t he and Leon exchanged addresses only a few days before? Didn’t Cherry agree to write to Leon’s sister and brother-in-law? Yes, now he recalled that clearly. How could he write? What could he say? He still did not know what he had done with the address. Tears welled up in Cherry’s eyes. He just got blown away. Just like that. Oh God, I can hardly believe it. Thinking about Silvers made Cherry feel very alone and very vulnerable. Them mothafuckers. Them mothafuckin dinks. I’m goina kill every mothafuckin gook slope I see. For you, Leon, you poor bastard.

Cherry’s thoughts wandered aimlessly through the darkest night hours. He thought of Linda. He masturbated, quietly shooting his juices into the cold muck outside his poncho. He thought about food, about eating. Eating is a very social behavior, he said to himself as if he were reading a study for a psychology class. It’s very important to boonierats. It’s the only time we kinda socialize. It’s the only time we talk. Man, there aint no social life here in the boonies except that twice or three times a day when we eat. Cherry felt a flash of guilt from his first days in the army, from his very first KP. He had not yet even been assigned to a basic training brigade. He was in the transfer center at Ft. Dix. They had awakened him at 0330 that morning to pull KP. All day he washed dishes and pots and pans and washed the dining hall floor between meals and at four in the afternoon he and three other KPs were ordered to cut up carrots and celery for the evening soup. Tiredly they chopped and sliced, carelessly cutting the vegetables, dropping them on the floor, stepping on them, picking up squished pieces and dropping them into the giant pots, laughing and joking.

Later he had been inserted into the serving line and he had ladled out the soup and had felt nauseous and guilty watching the other recruits and he felt even sicker when he thought about what others might do to the food he ate. Since that time he had always held a rigid standard about teamwork of army units, the communal eating, living, the communal everything, the total communistic society, the societal ideal so opposed by the military minds. And here in the army, he thought, who is the most vehement opposition to authoritarian communalism? It is the same political left draftee who comes very close, some indeed go beyond, proposing that all society should be communal. Not militaristic but communal just the same, communal but for the strongest advocates who would replace the old order with the new, and who would be at the top of the new order. And who would be exempt from the common communal life which they see everyone else living happily. The Great White Father in Washington looking after his boys wherever they are, wherever he sends them. What wonderful control, what complete authority. “Fuck it,” Cherry laughed. “Just say fuck it. Don’t mean nothin. Drive on.”

It was now light. Cherry watched Egan writing for several more minutes, then he got up. He sat on his ruck and brushed his hands through his hair and pushed out pieces of vegetation. His scalp was crusted with sweat and dirt. He had never been so dirty. Cherry felt his forehead, his nose. They were covered with pimples. On his cheeks his beard was a splotchy stubble which itched. His arm sores had become worse. He pressed about them. The wet scabs broke easily and oozed pus. His crotch rot was worse. The skin of his scrotum and inner thighs was red sore and white sore.

Cherry watched Egan. They did not speak. Egan carefully put his writing tablet and pens in the waterproof can at the base of his ruck. He removed a razor and soap and toothpaste. Cherry watched Egan shave in a puddle, watched how attentive Egan was to his cleanliness, even in the boonies. Cherry decided to emulate the platoon sergeant. He washed. With the corner of his towel he scrubbed his face and torso. He borrowed Egan’s razor and shaved. He shaved in his own puddle, leaving on only the sprouts of a moustache. Cherry scrubbed his arms. The scabs broke and the soap stung in the open sores. He brushed his teeth. He tightened his boots. He repacked his ruck leaving out coffee, cocoa, pound cake and fruit cocktail for breakfast. Instead of repacking his toothbrush he placed it in his fatigue shirt pocket so that the bristled end stuck through the pen slit in the pocket flap. Egan kept his toothbrush in his shirt pocket like that. Cherry wanted to emulate everything.

Now Cherry was eager to move out. He did not want to lie in the muck any longer. He fidgeted and adjusted his ruck straps again. He looked around. No one else was up. Cherry, you en your cherry ass, he assured himself, you’re getting it down.

He decided to write a letter. He rose, then squatted by his ruck. He extracted a plastic bag containing pens and writing paper. The paper was damp. Cherry sat back on the ruck. I should write to Silvers’ sister, he thought. I should. Cherry stared at the blank paper. He thumbed the edge of the page then began, “Dear Vic,” he wrote. I’ll write to the Silverses next, he told himself. “There must be a few things in the world more boring than sitting with an infantry company when they have nothing to do.” How can you write that? he asked himself. Twelve hours of quiet and you’re bored. Something is fuckin with my mind. He began again. “Don’t believe anything you read in the papers about Nam. In twenty days I know more about this place than in four years of concern back in the World.”

Cherry stopped again. Now how can I say that? Before I knew exactly where the government stood and I knew just what was happening. Now I don’t have any idea what we’re doing and everything the government said seems either to mean nothing or to be a lie.

He began a third time. “My mind came very close to total collapse these past few days. In five days in the field I have shot a man and I have seen my best friend killed. Yesterday I felt like vomiting. Today, immunity, sweet immunity is setting in and I’m finally crawling out from under my shell as the apathy and insensitivity take hold.”

A slap jolted Cherry’s shoulder and he leaped, grabbed for his rifle and swung around. Egan lurched for his 16 when Cherry jumped. Jax was in the grass between their rucks. “Rovers,” he whispered quickly to identify himself as a member of Alpha. “Doan shoot me Bros. It me, Jax.” He had a huge sheepish smile.

“Oh fuckin Christ,” Egan sighed. “Cherry, you make me jumpy as shit. Jax, what you come sneakin up on us for?”

“Yo guys up, huh?”

“Yeah,” Egan hissed.

“Marko on watch,” Jax explained as he wiggled his ass onto Cherry’s ruck and shared the seat. “I could not sleep,” Jax orated, his eyes twinkling. “I’s there all tucked up in my poncho an one big ol drop a rain squeeze hisself inside with me en join me bout the neck. I get cold, Man. Chills run up my pretty black neck, down my pretty black back. My toes get colder en yesterday’s cow flop.” Jax’ voice was in its best rhythmic gait. Egan laughed and tapped his feet in the muck in which he had slept. Here was Jax, after their words of the past few days, back to his old style. Egan felt warmed by Jax’ gesture.

“I looks up,” Jax continued. “An the sky comin almost light nough so yo know it there. I pulls my poncho over my head an rolls back over an tries ta sleep again. ‘Jest one minute,’ say Ol Mista Rain. I’s cold out here too. Yo let me come in there with yo an warm up.’ I says, ‘Aint no way, Mista Rain.’ But he doan listen an he squeeze in again an this time he saunter his sillyass inta my ear. ‘Okay, okay,’ I says. ‘I gettin up.’ Then I peers out en see Ol Mista Rain, he aint cuttin nobody no slack. I get up. I says, ‘body a Jackson, how yo this mornin?’ Ol bod say, ‘Beautiful cept my feet is faauuukkupp.’ So I says, ‘Why doan we go up en see Eg en Cherry? Yo know Eg aint never asleep.’ An sho nough, here Ol Jax right wid ya now.”

Egan held his right fist out and Jackson met it lightly with his own right fist as they dapped. The two fists tapped knuckles-to-knuckles and back-to-back. Open hands passed over each other in sensual caresses of brotherhood. Left hands came forward and touched and passed open over clasped rights and slid up right arms to shoulders then pulled across to the center of each man’s chest and clenched into fists. “I’m glad you’re here,” Egan said.

Cherry watched silently then got up suddenly, very quickly said, “Excuse me,” and rushed for the perimeter. A loose warm rush swept down into his bowels. He stopped, opened his pants, squatted. A watery brown gush sloshed onto the jungle floor muck. Feces splashed onto his boots. “Oh God, no,” Cherry groaned. “Not the shits.”

“Sky Devil Niner, Quiet Rover Four,” Brooks radioed Delta Company’s commander. At 1100 hours, after a lethargic morning, Alpha’s CP and 2d Plt began, moving north in column back toward the road. 1st and 3d Plts had patrols reconning to the south, east and west. At the NDP the remaining boonierats continued silent restful guard.

“Rover Four, this is Sky Devil,” the radio rasped in jocular reply. “Your wish is my command. Over.”

“What the hell?” Brooks muttered to El Paso. El Paso shrugged. “Devil,” Brooks transmitted, “my papa element is in your ballpark six zero zero mike to your sierra. We would like to play ball and will jump the red rope on your comic book to close in one hotel. Over.”

“Roger dodger, Rover. Check it out. Rendezvous with Sky Devils echo tango alpha one hotel. My team is ready to play ball and wilco. Over.”

“Thanks much, Niner,” Brooks said. “Out.”

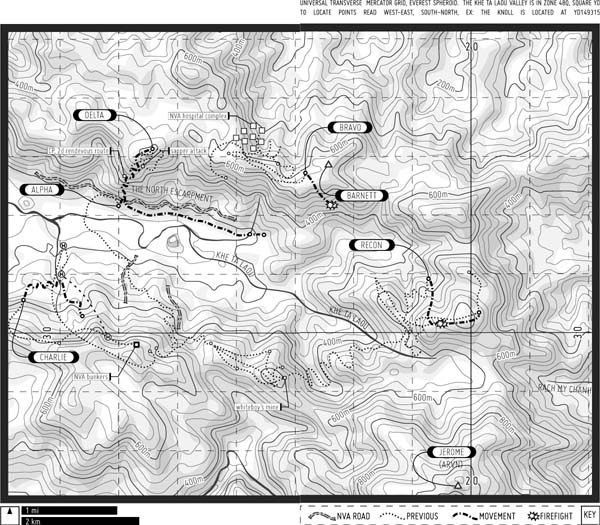

Delta Company had been moving back and forth on the north ridge for five days, being careful never to progress too far from their first secured LZ. Since daybreak they were to have been moving down the mountain toward the road and toward the rendezvous with Alpha. In reality only their CP had moved from a fixed position Delta’s 3d Plt had established atop the ridge to a fixed position Delta’s 1st Plt had 400 meters down a rocky finger. Alpha’s rendezvous element would do most of the humping.

Brooks signaled with both hands, thumbs jerked outward. 2d Plt and the CP quietly spread out through the grass forming a long line. Again on signal they moved now sweeping forward, slowly, approaching to within two meters of the road. There they halted. They stood completely still for several minutes then one by one squatted or sat to observe. In the midday light and with the higher fog ceiling the corridor was yet more awesome. The surface was composed of rock and gravel and the drainage system was elaborate. On the walls signs of natural material marked junctions and turnaround points. One eight-inch round from the pre-dawn barrage had impacted directly on the road. The explosion had cratered the road surface and destroyed a thirty-foot section of roof. The crater had filled with water. There was no other evidence of damage from the artillery. Brooks radioed the TOC with a new road description and the arty results. Then he cautiously moved forward. The flank gunners also moved to the road’s shoulder. They searched the far stretches. Through the hole blown in the roof Brooks could see a small cut in the cliff and a passageway up to Delta. He walked in the grass down the line, observing from various angles.

At Alex Mohnsen’s squad Brooks stopped and stood still. The squad leader came to him. “L-T,” Mohnsen whispered, “we aint goina NDP with Delta, are we?” Brooks did not look at him. “They’re the noisiest dudes in battalion, L-T.”

“I know,” Brooks whispered back not taking his eyes from the north ridge wall.

They were all silent again. They waited. The road remained empty. Halfway down the line Garbageman tapped one finger against his rifle in time with a silent song being played by a rock group in his head. Toward the far end, Hackworth muffled a cough in the crook of his arm, trapping the sound completely. He stifled the next urge to cough. And the next. Brooks stood rigid. Like everyone else’s, his uniform blended well with the grass. Mohnsen looked up at him several times. Brooks, motionless, was difficult to discern from even this short an interval. “Patience,” Brooks muttered beneath his breath. He was very aware of the suppressed restlessness of his men. Still they waited and observed.

After forty minutes Brooks moved. He returned to the CP. They rose. In both directions boonierats slowly stood, one by one. Brooks led off. He stepped from the concealment of the grass onto the road, crossed to the narrow cut and began climbing. He climbed slowly yet steadily. A stream fell through the cut. The water felt cold flowing in his boots. Behind the commander others crossed and climbed. Flank security remained out until almost the last man had crossed the road; then the flanks collapsed, crossed and followed. When the entire rendezvous element was on the mountain slope, Brooks paused. He was winded. The passage was steep, the climb exhausting. Pop Randalph crawled past him to take point. Lt. De Barti moved to slack. 3d Sqd slid in behind, then the CP, 1st and 2d. They climbed in column north, then northeast, always up, always toward Delta.

The vegetation on the north escarpment of the Khe Ta Laou was sparse and offered very little cover. Pop stayed low and stayed in gullies as he climbed. Behind him boonierats stepped into his footsteps. At just under fifty meters up the wall, Pop broke through the fog. High above the sky had a broken cloud cover. To the east there were patches of blue so bright Pop could not look at them. To the west over the Laotian foothills, the horizon was heavy dark and foreboding. Pop continued up. He climbed for half an hour reaching an area where the land leveled and thick jungle congestion concealed their advance.

“Tim,” Brooks whispered, “call Delta. See if they’ve got us visual.”

“Yes Sir,” Cahalan answered. The column continued. “Sky Devil, this is Quiet Rover,” Cahalan began.

“We see ya, Good Buddy,” came the flippant reply. “Just yall stand right up and walk on in. Ol Delta got you covered. We’re just thirty mikes up the high feature.”

Company D’s CP and 1st Plt were situated amongst a multi-peaked rock outcropping that overlooked the valley on three sides. On the fourth, the finger ridge ran perpendicular up to the main north ridgeline. The outcropping looked like a bartizan battlement on a castle wall, the sheered off south face aiming directly toward the knoll at the center of the valley. Alpha’s rendezvous element circled the position. The 2d Plt boonierats stopped outside the perimeter. Brooks, his RTOs, FO and Doc Johnson entered the perimeter and walked silently toward the center. From all sides came jeers. “Man, look what just dragged in.” “Hey, Hardcore, don’t go givin the old man any ideas.” “Aint that them crazy fuckers from Alpha?” “Break out the dew. Them dudes need a toke.”

Brooks walked erect, eyes forward, oblivious to the Delta troops. FO followed the L-Ts example, as did El Paso and Doc. Brown nodded to several of the men he knew. Cahalan paused to talk to an old friend. At the center of the NDP Delta’s CP had erected a poncho hootch large enough for six men to sleep beneath. Throughout the outcropping ponchos were stretched over bootlaces to make pup tents, or tied to rock walls to form lean-tos. No one had made any attempt to camouflage the shelters. Under every shelter there were men sleeping or reading. All of them appeared dry.

“Hi,” shouted Captain O’Hare from within the CP hootch. The Delta commander was a stout jovial man with a bushy moustache. His uniform was clean. His hands were clean. “Glad you could make it,” he called. “You’re just in time for coffee.”

“Hello, Peter,” Brooks said formally, softly. He squatted outside the hootch and looked in. Delta’s commander and RTOs had been playing poker.

“Come in, come in,” O’Hare persisted. “Sit down and grab a cup of coffee. Geez, this operation sure’s turned into a giant clusterfuck, huh? Why don’t you have your men come in and join me and my boys? Do you believe all this rain?”

“They’re okay where they are,” Brooks said coolly. “GreenMan give you anything for me?”

“I’ll say he did,” O’Hare said, “but first let me get you that coffee.” O’Hare rolled to his knees and crawled to the edge of the hootch where a ten-cup pot was steaming. “All the comforts of home,” he chuckled as he poured rich black liquid into a canteen cup. “Here.”

“Thanks,” Brooks said. He took the cup, sipped the coffee and passed it out to El Paso. O’Hare sighed. “Peter, I need all the bug juice you and your men can spare. My men are being eaten alive by the leeches in that valley.”

“Yeah, I was surprised to find you guys crossed the river.” O’Hare avoided Brooks’ eyes. “How is it down there?”

“Peter,” Brooks said, “I need insect repellent and I want to know what the GreenMan said.”

“Well, Ruf. Let me first say I’m sure glad the old man didn’t pick my company to go tricky-trottin down inta that. You guys just marched right through the middle of Gookville like you was comin down the middle a Main Street. I bet that scared them gooks halfway to hell.”

Brooks stood and backed away from the hootch a few steps, hoping to draw O’Hare out. “Shit, L-T. Look at that,” El Paso whispered from behind him. Several Delta troops on the perimeter were smoking and passing their smoke back and forth. The butt popped sending sparks flying. The soldiers laughed. “Holy Mother of God,” El Paso whispered. “They’re blowin dew out here.”

The personality of Delta Company was as different from Alpha as Brooks was from O’Hare. The companies were like brothers who had grown apart. On the surface Alpha was quiet, pensive, cautious yet daring. Delta was loud, boisterous, macho. In many ways Delta was a throwback to an earlier American personality in Vietnam which exuded bravado and faith in the American military way, while Alpha was the younger brother, taught tactics primarily by the NVA. Yet both companies came from the same parentage, the same battalion, division, country. The same technology was behind both, and the same can-do spirit, and the same ugly withdrawal symptoms sent from a country turned sour on war and demanding the return of its soldiers. Oh God, Brooks thought. Just let up a little, just relax and let them relax, and this is what you’ll have.

O’Hare came out from beneath the poncho roof. He had put on a rain jacket. “Did you hear, Bravo got another POW? They got em an NVA honcho.”

“When?” Brooks asked. He stepped away from O’Hare coaxing the other commander into open neutral ground.

“Earlier this morning. They killed another gook and got this honcho, and an AK and two RPGs. Can you believe it? Taking a prisoner in this shit.”

“Where’d they get them?”

“Another bunker complex. Those bastards are dug in all over this valley.”

“They weren’t moving?”

“Nope. Not from what I monitored anyway. They said both gooks were clean and healthy.”

Brooks signaled to Cahalan. The RTO approached immediately. “Get a full sit-rep on Bravo’s action,” he whispered then walked off pulling O’Hare with him. Alpha’s CP contingent followed at a distance. “How much bug juice did your men come up with?” Brooks asked O’Hare quietly.

“I’m sorry, Ruf,” O’Hare said sheepishly. “My boys don’t seem to be carrying much at all. I got three or four vials you can take.”

“That’s it?”

“Yeah. Like I said, we weren’t carrying much. If you’d radioed earlier I could have asked the GreenMan to bring some out. He dropped in yesterday and talked to me for about thirty minutes. Then his bird came back and he left. Can you believe, flyin in weather like this? Crazy, huh?”

Brooks had continued walking while they talked. Now he was at the edge of the cliff overlooking the valley. O’Hare stopped a few feet back. FO, El Paso, Brown, Cahalan and Doc stopped fifteen feet away. There were no Delta troops at the edge and indeed no perimeter positions along the cliff at all. Brooks seemed mesmerized by the view. He stared silently. O’Hare shuffled his feet. The valley was multiple shades of gray, the floor and Alpha’s lower element covered by a dirty thick gray fluff. Above was lighter gray, to the west very dark, the hills almost black, in the distant east unexpected patches of blue sparkling like jewels.

“Every time I see that mother,” Brooks said nastily, nodding toward the lone tree protruding above the valley fog, “it gets bigger. That’s one colossal tree. Look at that thing. Look at the size of that. Peter”—Brooks turned to O’Hare then turned back—” how far do you think that tree is from here?”

“About a klick,” O’Hare said.

“If you were up there you could see the whole valley,” Brooks said.

“Ah, Ruf,” O’Hare stammered, “do you want to know about the GreenMan?”

“Yes,” Brooks answered. He turned again and leaned casually against a rock at the cliff edge.

O’Hare began in alarm, “He wanted me to tell, ah, to offer you one of my platoons.” Brooks shifted. O’Hare stepped back another foot. “It’ll be op-conned to you while you’re down there. Ah, he, ah, thought you might need some more bodies.”

Brooks set his gaze on O’Hare’s eyes. Even leaning Brooks was taller than the stocky commander. Brooks did not move a muscle, his breathing was imperceptible. That’s why I don’t DEROS, he thought. That’s why. My men might get stuck with a man like O’Hare. I wouldn’t give any of them a fifty-fifty chance in the valley with O’Hare. “Peter,” Brooks said.

“Yes, Rufus,” O’Hare jumped nervously.

“Do you like small unit tactics? Harassment and attack?”

“Huh? Yeah. Of course.”

“So do I.”

“Oh. Yeah.”

“You’ll be up here—won’t you—if we get in trouble?”

“Yeah, Ruf. You know you can count on us.”

“You could probably be down to us in two or three hours if we were this side of the river.”

“Yeah. I’m sure we could. Ah, well. You know. It would depend.”

“Let’s just leave it that way,” Brooks said gently. “Okay?”

O’Hare laughed. “That’s what GreenMan said you’d do,” he said. “You know, Ruf, it’s good talking to you. You’re the only other commander I’ve spoken with in the bush in I can’t remember how long. We got to talk more often, ya know? We got to stick together.”

“Right on, Bro,” Brooks gave O’Hare a power salute.

O’Hare nodded furiously. “Sometimes it gets lonely out here, being in command. It’s good to talk to another commander. We understand each other.”

“Captain,” Brooks let the disgust come through, “if you need understanding, look to your men.”

Brooks rejoined his CP group and led them through the tiny hootchcity of Delta’s NDP. On their way out the calls came again, friendlier this time, “Go get em, Alpha.” “Do em a job, Man.” “Kick ass. Don’t take no names.”

Outside the perimeter, regrouped with 2d Plt, Brooks relaxed. He turned to FO, pointed and asked, “Bill, how far is that tree from here?”

FO glanced to the valley center. “Fourteen hundred meters,” he said. “Maybe fourteen fifty.”

Brooks nodded. “We’re going to circle that mother,” he said. “I want to go clear around it before we hit it.” The men around him nodded agreement.

They began the descent. Halfway down to the road the fog enveloped them. They paused. Brooks whispered very quietly to El Paso, “If you ever get a commander like O’Hare, waste him.”

At the road an eerie feeling swept through the rendezvous element. No one said a word. They crossed quickly and blended into the elephant grass. The crater which the eight-incher had blown in the road had been drained and partially filled. The hole that had been blasted in the roof was already less than half the size it had been when Alpha had crossed to climb to Delta. No one was around.

* * *

At dusk, forty minutes after 2d Plt and the CP reunited with Alpha, Alpha moved out. They moved in column, generally east, staying on the valley floor between the road and the river. 1st Plt humped between 3d at point and 2d at drag. Cherry quietly followed Egan. He was weary. Other than the few words with Jax and Egan at dawn Cherry had not spoken to anyone in twenty hours. When 2d Plt left for Delta, Cherry had manned 1st Plt’s CP alone. Egan had gone out on patrol, Thomaston set up a separate two-platoon CP where the company CP had been, McCarthy went with Hoover. Late in the afternoon Cherry had broken squelch on his radio and whispered, “Sit-rep negative,” in response to a call from El Paso. At that point he had realized those were the first sounds he had made in nine hours though he had been carrying on conversations in his imagination with himself, with his brother and with Egan. When Egan returned he had immediately waved Cherry into silence, pointed a finger in the air and circled. We’re surrounded, Cherry speculated. He began to indicate his puzzlement when the rush hit his bowels again and he sprinted for the perimeter. It was his seventh trip since daybreak.

While Cherry squatted, Whiteboy went running by, his pants half down, his hand on his penis. Doc McCarthy was chasing’ him with at least three cigarettes burning. Behind McCarthy, Hill, Harley and Andrews were all giggling, trying to keep silent, trying to keep up with the medic. Whiteboy circled back and Hill and Harley cornered him.

“Aw, Gawd A’mighty. Whut am Ah gonna do?” Whiteboy whispered. He was still holding his penis.

“Shoot it with Little Boy,” Harley laughed staring at Whiteboy’s groin.

“Here, Whiteboy,” McCarthy whispered catching up. He held up the cigarettes. “I’ll get rid of it for ya.” And the medic descended upon Whiteboy who let him get to within a foot then jumped back.

“Ah got to figger,” Whiteboy said. He half giggled at McCarthy approaching like that but he was obviously afraid and in pain. Cherry pulled up his own pants and approached. He looked at everyone’s object of concern. Hanging out of Whiteboy’s urethra was the tail end of a leech,

“Come on,” McCarthy chuckled. “I won’t burn off more than an inch. You got plenty ta spare and you aint usin that thing here, anyhow.”

Egan appeared, as always, seemingly out of nowhere. He immediately perceived the situation and produced, to everyone’s astonishment, a small bottle of bug repellent. Without a word he walked to Whiteboy, removed the bottle top and dropped half a dozen drops on the leech. It squirmed and began to withdraw. Egan squeezed several more drops on. “Hold still,” he ordered.

Whiteboy was nearly in tears of joy. “More, Eg,” he pleaded. Egan squeezed another drop. The leech seemed to back out further. “Whut are you, Eg? A junkie? More. Please.” Egan squeezed, another drop fell then the bottle deflated empty. Egan tossed it over his shoulder, smiled, shrugged and left. The others stood silently around staring at Whiteboy and the leech, stifling their laughs. Cherry ran back to his perimeter spot, pulled his pants down and squatted. Then he snapped upward and looked back for leeches.

Alpha forded several wide though shallow streams on the move east. They crossed all without ropes. Each time they crossed they proceeded in similar manner to the crossing of the day before, sweeping, pausing, observing before entering the open space. Each time Brooks felt the maneuver went smoother and quicker. With each stream crossing the vegetation changed. Alpha left the brutal elephant grass for the congestion of bamboo and then for a scary sparse low brush and sand meadow.

The valley floor here was a series of rolling swells. “Hold them up,” Brooks told El Paso when the CP reached the meadow edge. “Who’s at point?”

“3d Sqd, 3d Plt,” El Paso answered. He radioed the halt forward.

That dumb son of a bitch Caldwell, Brooks thought. He pulled out his topo map, made note of the location’s coordinates, looked up and ordered a slow withdrawal from the sparsely vegetated area. 3d Plt withdrew and the point headed south then east again skirting the meadow. Half a kilometer beyond the meadow, the point called a halt.

“What do they have?” Brooks asked El Paso.

“Cornfield,” El Paso said.

The CP moved forward. Before and beside the point there stood tall cornstalks in a well-cultivated field. Silently Brooks directed elements to flank the field. The column advanced from behind filling the voids created by the circling troops. Almost immediately 3d Plt found the field’s parameters. It was barely six meters wide and thirty meters long. Brooks led a sweep up the center. El Paso picked an ear of corn. He peeled back the husk. The kernels looked ripe and juicy. He cautiously licked the ear. No taste. He took a small bite. Sweet. He picked another ear and gave it to the L-T. Taste it, he signaled. Brooks did. Doc watched, picked, tasted, then picked several. Soon every man on the center sweep was harvesting the corn. Pick it but keep moving, Brooks signaled.

Alpha left the cornfield, reformed in column and climbed up and over the next swell east. Brooks called a halt. Brown and FO worked their way to the back of the unit and into a position to observe the enemy food supply.

“Fire mission, over,” FO whispered into the handset. The radio responded. To FO the handset felt alive. His words spoken into the small plastic and metal apparatus set the FDC and the gun bunnies scurrying. He was the eyes of the artillery unit.

“Rover Four, Two. Stand by for shot,” the radio rasped.

“Roger Two,” FO radioed. To Brown he said, “Pass the word, stand by for shot.”

“Shot out,” the radio sounded.

“Shot out,” FO repeated. Then he counted to himself, “… one thousand five, one thousand six …” Twenty meters above the valley floor a white cloud popped into existence. It was fifty meters right of the field. “Left fifty,” FO called. “Fire for effect.” Three HE rounds impacted across the near end of the field. Then three more. “Oh, oh. Boys, yo on the money,” FO cheered the arty unit via radio. The rounds passing over Alpha and exploding at FO’s command, even so near, sounded friendly. Up and down the line boonierats felt warmed by the violent eruptions. “Add fifty,” FO called. The field was progressively decimated. Half of Alpha’s boonierats crunched joyously into the sweet raw corn.

The rain became heavier as darkness closed about Alpha and the fog again descended to ground level. The unit moved cautiously through high discontinuous brush, moved generally eastward, the land slowly rising, the vegetation slowly thickening. When it was very dark the unit stopped, the column shortened and widened, the boonierats sat, covered themselves with poncho and poncho liner, ate, and set up LPs and guard watches. The CP meeting was concise and only Thomaston and Caldwell and the CP group attended. Cahalan’s report was also short. Bravo and Recon had both made contact, both in bunker complexes, both at the eastern edge of the valley. Bravo’s contact had taken forty minutes. They killed one NVA and captured one who wore first lieutenant insignias. Recon’s engagement lasted less than a minute. They also killed one NVA and captured one. Recon’s prisoner was half-dead, blown to pieces. Both prisoners were evacuated by medical helicopters. Except for Delta, all the other SKYHAWK companies were tightening their grip around the Khe Ta Laou. The gaps between the units were receiving continuous artillery H & I fire and constant high level electronic and infrared surveillance. There was no evidence of major enemy movements into or out of the Khe Ta Laou and intelligence teams suspected they had overrated the valley’s significance.

Cahalan’s report was followed by a brief discussion. Then Brooks said, “Tomorrow, we cross the river and check out the south bank.” The meeting ended. It was early, dark, quiet and cool. The night promised to drag by slowly. Half of Alpha slept, the other half fidgeted. Brooks too was uncomfortable. At 2300 hours he radioed 2d Plt and requested Pop Randalph to bring six volunteers to the CP. Ten minutes later Pop crawled into the CP circle followed by all of Mohnsen’s squad except Roberts and Sklar.

“Yes Sir,” Pop reported.

“3d’s got an LP due east fifty meters,” Brooks said to the assembled team. “I want you to go out to them, leave them there, move 150 meters farther east and set up an ambush site.”

“Aye aye, Sir,” Pop said. “I know just the spot.”

Brooks whispered a few questions checking out the team. He had Ezra Jones, Mohnsen’s RTO, contact the LP and inform them of the move. “Plenty of time, Pop,” Brooks patted the old boonierat on the shoulder. “Take your time.”

The team departed but still Brooks felt uneasy. He lay back and tried to sleep. El Paso was on radio watch. Cahalan was breathing easily. Minh and Doc were whispering a few feet away. Brooks crawled to them. Then Egan showed up. Then Jax. Then Cherry. The men formed a tight cluster. The discussion began almost as if it had not ceased the night before.

“Do you know who was the first American to die for freedom?” Doc asked.

“You mean here?” Cherry asked.

“I mean ever, Mista. I mean the very first.”

“Who?”

“Crispus Attucks,” Doc said proudly. “Killed in the Boston Massacre in 1770. That man won’t even free yet he died so your great-grandpappy could own mine. That man was a black slave.”

“Right on,” Jax laughed. “A black begun the first revolution an it was over blacks the second was fought. Now this black gowin begin the third. Let whitey eat my turd.”

“Oh, eat my asshole,” Egan snapped.

“The revolution is at hand,” Jax giggled. He was having a good time. “Come wid me, Bro, join our band. A new gov’ment we’ll give the land.”

“Look around, Man,” Egan said. “Is this what you want ta do back in the World? You want ta hump a 60 back there?”

“How are you going to overthrow the government?” Cherry asked seriously.

“We shall unite the people,” Jax said. “People of the world unite! Fight imperialist dogs! Stand up, be courageous! Advance! Wave upon wave of my people will descend upon the filthy butchers. We gowin form a platoon.”

“If one shot is fired” Egan took Jax’ bait, “your revolution’ll create a monster.”

Jax just laughed.

“You mothafucker,” Egan laughed back bitterly. “You mothafuckers talkin revolution. You just want to steal what other men created. Color only gives you an excuse.”

“They been doin it to us forever,” Doc said. “There aint no Brothers doin it out here. We all pullin our weight.”

Jax reached out and grabbed Cherry’s arm. “Bro, why doan you join us? Yo get back Jax gowin need a good RTO.”

“I got a long time to go,” Cherry avoided answering.

“You’re just tryin ta get over,” Egan sighed.

“Like au yo white granddaddies did on mine,” Jax said.

“Not mine, Man,” Cherry said.

“All the whites did,” Doc said.

“Fuck that,” Cherry whispered firmly. “My ancestors were serfs in Italy while yours were slaves here. Hey, Man, my grandparents came to this country in 1896 and at that time most of the Italians lived in crowded city tenements and worked in mills. Back then only twenty percent of all Americans lived in cities. My people were trapped there just like yours. But they didn’t go cryin to the government, ‘bus my kids to the WASP countryside.’”

“Course not, Bro,” Jax laughed. “They won’t no buses in 1896. Yo’d have ta a walked.”

“Ha,” Cherry huffed. “But my people didn’t stay there either.”

“Right on Little Bro,” Jax said. “Yo learnin. That jest what I’s sayin. We doan condone the pigs. Ef yo dowin whut they wantin yo ta do, yo helpin ta perpetuate their system. The revolution is at hand. Join us.”

“People are dumb,” Egan injected. “They’re dumb and they’re apathetic and they like to be used. They don’t like to make decisions or to be responsible. Even for themselves. They want to be led. They want to be exploited.”

“Do you really think so?” Brooks asked softly. He was enjoying the conversation, and now too, the night.

Egan looked through the blackness toward Brooks. He was aware of the L-T’s debating skills and he proceeded cautiously. He had already committed himself. “Yes, I do. Look around. You have to beg people to be platoon sergeants, even. There’s a dozen guys in 1st qualified to be platoon sergeant who are satisfied sitting back puttin in their time.”

“Jax,” Brooks’ soft whisper floated in the black mist. “Why do you think the people allowed themselves to be exploited by a … an elite?”

“That whut I’s sayin, L-T. We doan condone it no mo.”

“But blacks did before?”

“They had to.”

“Could it be as Danny said. They were too lazy or simply did not care?”

“Lazy and shiftless, L-T?” Doc whispered nastily.

“What do you think, Minh? Your country was exploited for a very long time. Could the people secretly have wished to be members of the elite and thus wanted it to remain?”

“Oh no, L-T,” Minh’s whisper was high and thin. “I do not think this is so. But it may be so. To have an elite you must have the masses, yes? Perhaps they are a unity. Perhaps one cannot be eliminated without eliminating both. And then who remains?”

“Huh?” Cherry uttered.

“Thank you, Minh,” Brooks said. “Maybe we should think about that. Perhaps many blacks in the World no longer want to be used. Perhaps they now refuse to condone being automatically relegated to society’s lowest levels. But they’re not, no matter what they say, on the road to destroying the country. Perhaps they are securing the perpetuation of the system by fighting to be the elite. Perhaps they are out to build a better country.”

“Like they built a better Watts?” Egan suggested sarcastically. “Or maybe a better Detroit? By rioting and burning the place down? By forming guerrilla platoons, secret armies, to overthrow the government?”

“Guerrilla groups doan just happen, Mista,” Doc said. “Riots doan just happen. You know that. They produced. They produced in a kind a society where there’s hopelessness.” Doc paused. He flashed on hot summers in Harlem, heat wave days when the TV crews showed up to film eggs frying on car hoods and black children playing in the gushing water of fire hydrants. It always looked like so much fun. Like an amusement park. Inside the tenements, unfilmed, men lay sprawled, near naked, gasping for breath. Only the putrid air seemed more listless than the jobless old women who sat unable to move. Very old people died in their rooms unnoticed until evening when they were carried out. The evening brought little relief from the heat. Doc remembered the summer when Marlena, a tiny child, was nearly killed by roof rats in her makeshift bed. For a month the wounds on her legs seeped. Doc cleared his throat. The others were silent. “Riots doan just happen,” he repeated sadly. “They come from despair, Mista. You know what I mean? They doan come from repression. They come from crushed expectations. It aint far from hopelessness to riots.”

“Doc, I don’t understand. I don’t see things as hopeless,” Cherry said easily, trying to sound sympathetic yet encouraging. “I see opportunity everywhere.”

“You brought up that way, Mista. You see people makin it. Where I come from, I see people wastin way. Hopeless, Man. You can say what you want but nobody listens. Like you. You can’t hear me. They pass laws, they say they spendin money. Nothin happen. Jax right, Bros. The government gonna fall. It’s the government who decide who live, who die. The government decide who drafted, who shipped to Nam, who a boonierat, who get jobs, who starve.”

“It’s not that way for everyone,” Cherry said.

“The revolution is comin,” Doc said very sadly. “It comin an the government can’t stop it. They can’t stop it cause the guerrilla is the heart of the people. The heart of the people that the government discards.”

“Maybe you dudes are right,” Egan said. This time he had really listened. What was being said went against much of what he believed but he could not deny it. “It’s right to say the government’s in control. They got the guns. All political legitimacy comes out of the barrel of a gun. All human rights, speech rights, property rights. If you really don’t have them maybe you do have to revolt. I take back a lot of what I said. If the government tries to take your freedoms you got to revolt. That’s power out of the barrel of a gun. Americans have traditionally had a low flash point. That’s why we know such great freedoms. And you’re right. We are losin it. We’re losin it little by little to the Nixon machine and to the bureaucratic machine. But you know somethin? We’re askin to lose it. We’re sellin our freedoms one by one to that bastard. We’re sellin it to be taken care of by a paternalistic government. And that’s cause people are lazy and they don’t care. Yeah. If you gotta revolt, that means you care.”

“Right on, Bro,” Jax whispered.

After a pause Brooks said, “It is important for us to understand how racial violence occurs if it is to be avoided in the future. Doc, you said something just now that really hit me. Race riots don’t just happen. Wars do not just happen. Would you do me a favor and ponder that? I want to talk some more, but later.”

The little group broke up and the men returned to their positions. Brooks went to his ruck and silently removed a stenographer’s pad from the waterproof ammo can at its base. The time had come. He would write down his observations and thoughts about conflict. In the dark he wrote carefully, large and cryptic. On the cover he printed, AN INQUIRY INTO PERSONAL, RACIAL AND INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT. On the first page he wrote: Conflict does not just happen. Wars do not just happen. Divorce does not just happen.

Then he put the notebook away. To himself he said, I must DEROS now. I must write my dissertation. I’ll radio GreenMan in the morning. Should I tell anyone else?

Why do I always come out sounding like a bigot? Egan asked himself. He and Cherry were back amongst 1st Plt. Egan mulled over the argument with Jackson and reviewed the other conversation at the CP. He did not, could not, believe he was a racist. He would not even describe himself as right wing. He believed he was very open minded, very much a man who weighs all sides of an argument.

Cherry’s whisper disrupted his thoughts. “What?” he said.

“How do you think Jax and Doc and the L-T feel about you comin down on blacks?” Cherry repeated.

Holy Shit, Egan thought. Was I that bad? Egan spoke softly in that jungle-night voice developed in veteran boonierats, a firm voice with almost no sound. “Boonierats is a race,” he said. “We can say things like that. Nobody takes it personal.”

“Not even you callin Silvers a token Jew?”

“You don’t understand yet,” Egan said. “Takin it personal is for people back in the World. We got a separate culture out here. And in some respects it’s better. Fuck Man, an AK round don’t care what color your paint job is.”

Cherry took a deep breath and exhaled slowly. “You got no feelings, Eg,” he said. It was the very first time Cherry had ever used the nickname. He felt slightly apprehensive yet it brought him to Egan’s plane.

“You don’t understand, Man,” Egan said. “You’re goina have to experience it all for yourself first. I got feelings.”

“Goddamnit,” Cherry grunted. “I don’t understand you. I think you just hide in that hardass role you’re always playin.”

“What?”

“Silvers gets blown away. Brunak gets wounded. You either don’t care or you hide it awfully well.”

“Man, you’re bein an asshole.”

“Silvers got blown away. I’ll never see him again. He’s dead, Man.”

“What difference does that make to you? Or to me?” Egan was feeling quite heated. “He’s dead. You want me to write his folks and say, ‘Ah, I knew yer kid. He didn’t die bad. There wasn’t time for pain cause he caught it in the neck.’ Maybe you’d have me go easy. Say, ‘He got it fuckin a sleeze in the ville at the height of orgasm.’ What the fuck do you want from me, Man?”

“Nothin,” Cherry said. Their conversation wasn’t going as he had expected.

“Look, Cherry,” Egan calmed. “If I’m goina mourn for a dude, I gotta do it in my way, in my time. Man, boonierats are different kinds of people. You want to think about Silvers, think about why he got blown away. For me, I gotta think about what to do. I had to replace him, make Jax squad leader. That wasn’t easy. Marko and Denhardt both could a been made squad leader.”

“You didn’t do that cause Jax is black, did you?”

“Fuck no. Denhardt’s got no brains at all and Marko couldn’t lead his grandmother through a supermarket without antagonizing her. I mean it when I say boonierats is a race. Look, I love these guys out here. I know I can depend on em.”

Cherry did not answer.

“One night on 882 we had twenty-eight wounded,” Egan said. “Everybody seemed to be bleedin. Black, white, yellow. None of the docs said, ‘Go find a medic yer own color. I only treat my kind.’ The docs treat everybody. Pointmen lead everybody. When some of those dudes died everybody felt bad. Jax felt for his white boonierat brothers just like I felt for my black ones. It don’t always show. And I hate to see fucken blacks riot in the World. Fuck it. I don’t think it’s s’pose ta show.”

Cherry and Egan lay back. Cherry was on radio watch. Egan passed quickly from awake to semi-consciousness. His mind zigged and zagged in agitation. Stephanie appeared and calmed him. He watched her form, the image solidify. The sun came out. It was spring and warm and the air was sweet with the smell of fresh cut grass. How had he ever let her slip away? Perhaps he hadn’t. Perhaps she would be there when he returned. The closer he came to his DEROS and ETS the more he thought of her.

Daniel Egan visited Stephanie often during the summer of her divorce and through the following autumn and winter. His memory exploded with small anecdotes of those days. His entire body burned with desire for her. The soft sleepy neck of Stephanie rose from a woeful droop and swung back tossing her hair in a gleeful, careless arc. Her eyes glistened. Her moist lips trembled with laughter. Come, her image beckoned to him. Come with me. On the jungle floor Egan’s body quivered in resistance. Come, she beckoned. His body shook. He felt at peace. Smoothly, silently, pleasantly, his spirit slipped from his body and joined Stephanie in the image in his mind. For a moment Daniel glanced back at the soldierly figure, the cold filthy miserable body crumpled on a hundred-pound pack, then the spirit turned its back and smiled at Stephanie. They strolled in a glistening world by a small stream. Before them a stone bridge arched.

They walked to it and crossed and walked on to a pond. The day was warm. Fat-leafed maples reflected in the water. Daniel broke pieces of bread from a loaf he was carrying and tossed the pieces to the ducks swimming nearby. The colorful birds paddled closer, a few even came out of the water to feed near their feet. The ducks fought one another aggressively yet they remained timid and watchful as Daniel tossed the food to them. Stephanie knelt down by the water’s edge and the ducks came to her and took the bread from her hand. She sat back and the ducks stretched their necks across her lap. She stroked them tenderly and they ate. Daniel inched nearer to pet one. They all scattered. We’re all like that, he had thought. Anyone can come to her without fear, yet she herself is so timid. She’s so strong yet so timid.

“Do you remember the book you left me in New York?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said lying back.

“When you came back I told you I hadn’t read it.”

“I remember.”

“You said, ‘I knew you wouldn’t.’”

“I didn’t say that, did I?”

“Um-hum, you did. If you bring me The Sun Also Rises, I promise I’ll read it. I started Hawaii two weeks ago.”

“How do you like it?” he asked.

“I’m really enjoying it,” Stephanie laughed, “but I must admit big books kind of scare me.”

The image flowed. The physical being on the jungle valley floor pushed it, trying to force it, to speed it up as if time were running out and the body wished to relive as many episodes as possible. “I received your book today,” Stephanie’s voice came to Daniel over the phone. He was back at school. He had sent her his battered copy of The Sun Also Rises. “It’s a beautiful book,” she said. “I haven’t started it yet but I like to touch it and to look at it. It’s beautiful.

“I’m sending you my Sandy Bull album, Fantasia. I think it’s more me than any others I have or anything else I have, except my eyes. Which I can’t give you though I’d like to.” Stephanie laughed gleefully for a time and Daniel laughed though no sound came from him. “I’m reading The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand,” she said. “You’ve probably read it but if not I’ll send it to you. I really like it and Howard Roark reminds me of you. How is the Alaska house coming? Please don’t forget how much I want to see your drawings.”

On some plane in between, Daniel Egan was aware he never showed Stephanie the Alaska house drawings. Now, in another image, she let him have it. They were in a small upstate bar, Stephanie was sad and serious and so delightful. “I told myself I wasn’t going to do this but I am. You know, Daniel, in some ways you’re very selfish. I know you know it. Talk to me, Daniel. I know it’s there but you won’t give it to me. I love you and hate you for doing it.

“Daniel,” she pleaded, “I want, and I am trying, to come to your level. Oh, that sitting back level, that observing confident level. I want it. I’m getting it. But Christ, Daniel, will you talk to me? Are you doing it purposely? I bet you are. I can meet you there. TALK TO ME! You bastard. You beautiful bastard.”

“Stephanie,” Daniel answered her now an answer he had never given. “I care. I care for you more than for anything else I’ve ever known. I just don’t know how to say it.”

His thoughts sped on. Stephanie, I’m striving to gain your level, the level of natural humanity uncluttered with mass produced technology. I care for you … I care … I love … I love you.

“I’ve been volunteering at the daycare center.” Stephanie smiled. They were lying together. The day had been exquisite and the night was warm. Stephanie was happy and sorrowful and troubled. “I’ve been working in a room with eleven children, seven of which are Negro. The first day I walked in all I had to do was smile and there were six children hanging around my neck and on my legs. They seemed so starved for affection. This one little boy named Jeremiah is one of my favorites. Daniel, he is just darling. I want to adopt him. His mom is on relief and she’s an alcoholic. Jeremiah comes to the center with no underwear, pants five sizes to big with the zipper broken and the pants pinned to his shirt so they won’t fall down. I went to a rummage sale and bought him underwear and shirts and sent them home with him. The next day his mom sent a note with him saying she didn’t mind Jeremiah coming to the center but she did not approve of us trying to buy his love with clothes. Wow, Daniel, I was really hurt. I guess I’ve got a lot to learn.

“Oh, Daniel, there are some sad moments but mostly we really have fun. I could go on and on about the funny things the children do. I wish you could see them. You’d love them too.”

Daniel sat and listened and loved her for being so enthusiastic and so sensitive and for loving the children. But he said nothing except to ask her if she’d given up art completely. She responded in a way he never understood. “Daniel, no one will ever really know, will they? No one will ever know what’s inside you. They can get an idea but they’ll never really know. That makes me sad.”

“I’ve always believed,” Daniel’s image sounded very far off, “that a person is what he does. A person is what he accomplishes, what he creates. An artist, for example, is a person who creates art. It’s not one who fosters the image to others that he creates art when in fact he creates nothing. That’s a pseudo-artist. A person who takes care of children is a child care specialist. That’s who they are. Do you see? If you are what you do then identity crises are caused by not knowing what to do or by not doing. An identity must be constructed by doing, creating, building …”

“How about by reading and thinking and dreaming?”

He heard her say that now. He saw the hurt on her face now. Why wouldn’t I allow myself to hear her? he asked now. I was a bastard.

Again, tumbling through weightless voids and into another scene. His body no longer wanted to push the fantasy. He no longer wished to reexperience all their times yet he was out of control. The picture flowed at its own speed, its own discretion, on its own energy. It was the same scene he had remembered the day of the CA but this time it was clearer and their positions were reversed. They were in a room in the old Martinson Hotel which looked out across the railroad tracks to a dully lit cobblestone street. It was raining. Daniel was standing by the only window in the room. The empty eyes of the stores across the tracks, across the street, reflected mud-ash earth and debris. On the corner up the street a tavern sign flashed Iron-City Beer—On Tap.

The window sill and frame of the hotel room were partially lighted from the light of the street. The room was dark with the exception of a single candle burning in the corner. Stephanie lay in the bed looking at Daniel’s back. The room was old and dingy. Stephanie rose, circled the bed and put her arms around Daniel’s shoulders. She lay her cheek against his back. Daniel turned and she let go. She was still naked. She stretched her hands gracefully toward him, he took them softly and held them then brought her to him.

“I’m sorry, Steph,” he said. “I didn’t understand.” It was his spirit speaking. It was not his image. He had hurt her while they made love. During his campus exploits he had developed a harsh dominant athletic style which did not suit Stephanie at all. Harshness hurt her. The abortion had left scar tissue at her cervix which caused her pain on deep thrusts. “I’m sorry,” Egan’s spirit said. “I’m sorry for all of this. Someday, I’ll make it up to you.”

After that time he did not see Stephanie for many months. Now watching the lone mirage he thought how insensitive he was to all the things Stephanie said. That is the tragedy of his life. He was not sensitive to Stephanie when it had been possible. He had not even been sensitive to his own feelings. The hallucination rolled and shook violently. He was above his own body, his cold wet sleeping body wrapped in poncho and poncho liner. Squatting beside him was the sapper. The enemy smiled—his teeth glistened. I’ve got you this time, the soldier seemed to say to the hovering spirit. Slowly the machete lifted. In slow motion the dark foe whipped the silver blade in a circle then powerfully brought the blade down toward Egan’s face. “I’ve got to get back,” the spirit cried. “I’ve got to get back into my body. I’ve got to help him.” The spirit was frantic, the body on the ruck cowed, the enemy blade descended in slow motion. The razor sharp edge pierced the bridge of Egan’s nose. Slowly the blade, driven by the might of the enemy’s powerful hand, cleaved into Egan’s eyes dividing the orbs. The spirit slipped back into Egan physically expanding his cringing viscera. A series of small explosions shook his ears. Then an M-60 opened up far to the north.

“What’s that,” Cherry whispered.

Egan grabbed his face. He was silently crying.

In the dark, in the rain, two NVA sapper teams noiselessly crawled up the cliffs of the north escarpment to the rock outcropping which held Delta’s NDP. Below, half of Alpha was asleep, half was on vigilant watch. Egan was in the midst of dream. The sappers slid silently to the perimeter edge then froze and observed. For two days the NVA had been watching the Americans from above. Delta barely altered their alignment from the moment they set up and they quickly established a routine movement pattern. The sapper unit studied Delta’s fighting positions, the positioning of the poncho hootches and the behavior habits of Delta’s troops. They carefully conceived and detailed their attack. At dusk they began to execute the plan.

The two teams climbed straight up the cliff, one settled among the rocks at the cliff edge, the other veered and followed the path which Alpha’s rendezvous element had used during the afternoon. For three hours the sapper teams motionlessly watched as Delta troops fidgeted and fussed and divulged their positions. Then the team at the cliff edge penetrated the perimeter. The sapper team leader found two Delta soldiers asleep with their M-60 machine gun on bi-pod between them. Noiselessly the sapper thrust a thin-bladed bayonet into the first soldier’s throat. He drove the blade upward toward the back of the head, twisted and withdrew. The body twitched then relaxed. Next to him his buddy slept on. The sapper cautiously circled the dead man. The second guard awoke, startled. He tried to sit up to scream. The sapper smashed stiff fingers into his Adam’s apple knocking the man back, stifling his scream. Then, quickly, he bayoneted the man’s throat. The team infiltrated the NDP, worked to predetermined points among the rocks and brush and became rigid. At Delta’s CP two men were smoking.

The second sapper team remained outside the perimeter. Slowly, soundlessly, they crawled about Delta’s claymore mines. As they found each one, they turned it around and aimed it in upon the defenders. Then they all lay quietly. After a pause of fifteen minutes the outside sapper team again began to move. They made a little noise. Delta did not react. The sappers moved again making more noise.

“Sir,” a Delta perimeter guard came to the CP. “I think we got movement inside the claymores.”

“You see anything?” O’Hare asked. He was up. He put out his cigarette.

“Whatcha got, Bobby?” an RTO asked.

“I aint sure. Bat Man thought he heard somethin.”

“Throw a frag at it,” the RTO said.

“No, wait a minute,” O’Hare said. “Call the firebase,” he directed the RTO. “Tell em we want some illum.”

The guard returned to his position and several minutes later a mortar-launched illumination flare popped over Delta casting the rocks and vegetation in a queer flat light. The sappers remained low and motionless. More flares popped and floated gently downwind on their parachutes. The sapper team within Delta’s perimeter eyed their foes. The illum glimmered on the wet poncho-hootches. More flares popped. The mortar team kept the area lighted for twenty minutes until O’Hare cancelled the mission. Delta went back to sleep.

Two hours passed. The sappers had not moved a hair. Delta twisted beneath their poncho tents. “Let’s keep it down,” O’Hare called out to a perimeter position at one point.

“Augh, Sir, it’s Willie,” a troop called back. “The fucker keeps snorin.”

A third voice called out, “Bullshit. Now shut up.”

From another position a man giggled. Then the chatter subsided and Delta slept again. The sappers moved. The outside team infiltrated between two sleeping guard positions. The inside team spread out. On a single click-signal all the sappers unloaded and fused their sachel charges. Then deftly they placed the charges by and where possible between the heads of the sleeping Americans. Immediately they began their withdrawal. The first team in crawled back to their cliff entrance and grabbed the M-60 and the ammunition. The second team crawled out. The first sachel charge exploded. Then another and another. All the GIs were up. People were running, screaming. More sachel charges exploded. O’Hare’s RTO found one between him and the captain and flung it out of their hootch. It exploded wounding a perimeter guard who had run for the CP as the blasts began. Someone yelled, “SAPPERS!” An M-60 opened up firing into the NDP. Other soldiers fired at their own men. Several Delta troops began running, shouting, trying to organize the unit. The M-60 fired upon the running troops. There was mass confusion. Delta did not know who was who. Then came a quick succession of small explosions.

Explosions vary in length of time depending upon the amount and type of explosive. A quick explosion makes a sharp sound. Slower, longer burning materials cause a deeper sound, more of a roar. The sachel charges were slow and of relatively little power. The first few blew heads apart but most at best only blew out eardrums or eyes. At Alpha, a kilometer away, the old-timers recognized the sound. Four months earlier, on Hill 714, the NVA had killed five Alpha boonierats using similar tactics. Now the NVA were throwing sachel charges into Delta’s perimeter to increase the chaos, get the GIs up and running so they would be shot by their own men.

The unmistakable crackblast of a claymore resounded from Delta. Everyone in Alpha was up then down. Alpha lay perfectly still, prone, in the mud. On 100 percent alert. At Delta a perimeter guard had squeezed his claymore claquer firing device. The claymore removed his face.

“What’s that?” Cherry whispered to Egan.

“Sappers. Nobody up there firin. See if you can monitor.”

“I don’t know their freq.”

A call came from El Paso. “Pass the word. Sit tight.”

Egan slithered off to check his platoon. “Lie quiet,” he repeated to each position. “Ambush team and LPs comin in. Watch for em. Don’t fire em up.” At Jax and Marko’s location Egan found the two talking. “Stop the chattering. Keep it down.”

Jax rolled over. “Oh Man. Cut it out. If yo was a dink, would yo come tricky-trottin inta our AO? Theys fuckin wid Delta, Man. They aint even gowin fuck with us after they woke everybody up.”

El Paso radioed the platoon RTOs. “L-T says we’re movin when the Dust-Offs come. Have em packed up.”

When the medical evacuation helicopters reached the Khe Ta Laou they repeated the night medevac procedure they had used when Bravo had been hit five days earlier. A flare ship circled high above dropping flares and illuminating the entire sky. Four Cobras and two LOHs escorted the four Dust-Off Hueys. Above the flock of birds was the charlie-charlie of the GreenMan. The noise was tremendous after the silence of the night.

On the valley floor Egan led off. Jax walked his slack. The LPs and the ambush team, all accounted for, formed a rear drag. The light above the medevac site glowed in the fog over the valley but on the ground it was dark. Egan bulled his way through the vegetation. He did not cut a path. He moved slowly. Sometimes he crawled, sometimes he sidestepped, but he never stopped. He used a lensmatic compass for direction and he led Alpha east. He walked as if he knew the terrain, as if he had been expecting to lead the column on this exact move, as if he had practiced it. The medical evacuation from Delta took over an hour. The birds did not extract all the dead or the routine wounded. They would be evacuated during daylight. The birds removed only the eleven seriously wounded.

Alpha had moved almost 200 meters east by the time the last medevac and the escort fleet left the valley. Egan stopped. He sat down and waited as Brooks had instructed. Behind him the entire company sat. And sat quietly for the rest of the night. The next day would begin their fight.

SIGNIFICANT ACTIVITIES

THE FOLLOWING RESULTS FOR OPERATIONS IN THE O’REILLY/ BARNETT/JEROME AREA WERE REPORTED FOR THE 24-HOUR PERIOD ENDING 2359 18 AUGUST 70:

RAIN CONTINUED ON THIS DATE THROUGHOUT THE OPERATIONAL AREA CAUSING THE CANCELLATION OF 18 TAC AIR SORTIES AND THE POSTPONEMENT OF ONE COMPANY-SIZE ASSAULT.

ONE KILOMETER WEST OF FIREBASE BARNETT, AN ELEMENT OF CO B, 7/402 ENGAGED AN UNKNOWN SIZE ENEMY FORCE IN A BUNKER COMPLEX KILLING ONE NVA AND CAPTURING AN NVA 1ST LIEUTENANT. THE POW WAS EVACUATED FOR INTERROGATION. THE UNIT ALSO CAPTURED ONE AK-47 AND TWO RPG LAUNCHERS.

LATER IN THE MORNING, RECON, CO E, 7/402 WAS AMBUSHED BY AN UNKNOWN SIZE ENEMY FORCE IN THE VICINITY OF HILL 848 AT YD 193303. THE UNIT RETURNED ORGANIC WEAPONS FIRE KILLING ONE NVA AND CAPTURING ONE POW. THE POW WAS EVACUATED FOR MEDICAL TREATMENT.

AT 1805 HOURS CO A, 7/402 DISCOVERED A CULTIVATED CORNFIELD VICINITY YD 158320. THE FIELD WAS DESTROYED BY ARTILLERY FROM FIREBASE BARNETT.

ARVN UNITS MADE NO SIGNIFICANT CONTACTS ON THIS DATE.