CHAPTER 27

20 AUGUST 1970

By first light the raindrizzle had ceased. Alpha was socked in beneath thick valley mist. The boonierats hardly moved. For an hour the only noise was the RTOs calling in situation reports and resupply requests and Brown calling in the altered supply order for now seventy-five men. Doc Johnson had convinced the L-T to send Whiteboy to the rear because of the big soldier’s eye wound. Melvin Harley would act as squad leader until Whiteboy returned.

Alpha rested. Today would be resupply day and they anticipated none of the complications of the last resupply. Brooks cut them as much slack as he dared. He sent out only three five-man patrols, one from each platoon, and they were instructed to stay relatively close. “Just have a look around,” he had told the platoon leaders. “Get us some targets for arty, collect intelligence, but avoid engaging the enemy if possible.” Everyone had agreed enthusiastically and had left Brooks alone in the dawning while he called the GreenMan.

“Red Rover One, this is Quiet Rover Four,” he radioed. He was not sure how to proceed. He had a personal request.

Brooks spoke with the TOC RTO and finally got the GreenMan. “Four, this is One Niner. Over.”

“One,” Brooks addressed the GreenMan. How could he say it other than just saying it? He could not think of a way. “One, Quiet Rover Four Niner requests to delta echo romeo oscar sierra on two eight August. Over.” There! Finally he had said it. There was a long pause. He wanted to DEROS in eight days. He would be out of the field in five days or less. His decision was made. Now it would be up to the GreenMan to approve it and up to Personnel to implement it.

“Four,” the GreenMan’s voice came from the handset, “that’s a rodge. That’s affirm. I have you deltaechoromeooscarsierra on two eight August—providing Texas Star reaches termination. Four, I need you. Over. Out.”

There had been no CP meeting the previous night because of the fleeing and hiding. In the unreal security of dawn the usual boonierats gathered at the CP. They felt extra tired, extra irritable, yet they generally maintained the macho, though dampened, facade of young soldiers.

Cherry sat quietly monitoring the various companies’ internals about the valley. Doc, Minh and Whiteboy spoke quietly among themselves. Brown and Cahalan shared a cold can of Spaghetti and Meatballs. El Paso monitored the reconning patrols and he and FO plotted targets. Egan painstakingly cleaned his weapon. Thomaston, Caldwell and De Barti savored the smoke of a single last cigarette.

“Hey, Eg,” Thomaston called lowly, “how many today?”

“Eighteen en a wake-up,” Egan answered. “What about you?”

“Twenty-one.”

“You cherries,” Brooks laughed. “EIGHT!” he announced.

“Is that fucken right?” Thomaston said astounded.

“You finally decided,” Egan added.

“You owe it to yerself,” Doc said. “Right on.”

“I didn’t think you’d ever leave,” El Paso smiled.

“But I still have eight days,” Brooks said. He was happy and they were happy for him. “Let’s get down to business.”

The boonierats closed in about their commander. They whispered one-to-one the cliches they always whispered when a boonierat brother left. “Get some for me.” “Look out, Mama, Daddy been holdin it so long, it gonna explode.” “I bet he shoots his load before he ee-ven enters the door and still blows her eyes out.” “Bet yer ass he will.”

“Well,” Pop Randalph smiled at them all, quieted them as he leaned into the center of the circle, “when yer twenty you can send a squirt right across the room. When yer twenty-five you still got enough muzzle velocity to fire from the hip. But, I gotta let yall know, when yer thirty-seven, goddammitall, it’ll still come out with a bit a coaxin but you best have a bucket under it. How old are you, Sir?”

“Old enough to reach halfway across the room,” Brooks chuckled.

“Why, hell. Here all this time I thought you was seventeen.”

They all laughed then Brooks put a damper on the meeting. They discussed yesterday’s ambush of Mohnsen’s squad. What happened, why it happened, how it could have been avoided. “Recon elements should not pursue ambushers,” Brooks said. “It’s the same damn thing that happened to Bravo down on the Sông Bo. They sucked them in then blew them away.”

“L-T, I don’t think you can say that,” Lt. De Barti challenged him.

“I agree, Sir,” Pop said. “You gotta return fire, suppress their fire, an gain fire superiority. Otherwise they goan eat you up.”

“Not a seven-man recon element,” Brooks said. “When they began taking fire they should have held their position until maneuver elements could have flanked them.”

“No Sir,” Pop said. “I disagree. Most times you can’t wait for nobody. You gotta break the back of a ambush.”

“That’s true,” Egan said.

“Yes,” El Paso agreed then tried for a compromise, “but I think what Mohnsen did was run through his ambush. They should have stopped the second they realized there were enemy on their sides. They could still have disengaged.”

“Hey,” Brooks said. “Listen. As long as I’m in command here, recon elements are to return fire but to disengage as rapidly as possible. They are to wait for reinforcements or for arty or ARA. That’s it. Any questions?” No one answered. Egan bit down and tightened his jaw. Pop examined his fingers. The weariness that was in them all seemed to seep to the surface. Brooks removed his odd baseball-style hat and scratched his scalp. “We’re going to have plenty of opportunities over the next few days to mix it up with Charlie,” Brooks said. “Don’t worry about that. Green-Man still wants us to clean out this valley. After resupply we’re coming back here. We’re going for their heart.”

Before Alpha moved out Brooks walked to each platoon. He wanted to tell as many of his men as was possible. He especially wanted to tell the old-timers. He wanted to say he was leaving them but not abandoning them. That was always bullshit. It seemed everyone always said that in one form or another just before they DEROSed. Then they would leave and perhaps send a letter or maybe even a package. But soon that ceased and they were out of touch; the old unit was filled with cherries and the vet was surrounded by a different and demanding world. But Brooks believed he would be different. He would not forget. He wanted them to know that. Slowly he moved to 1st Plt’s area. He carried only his weapon and a notebook. Yes, he thought. It is also time to write down their views and perceptions on conflict. Perhaps, in the next five days, I can make enough notes to lay the foundation for a thesis. And yes, one thing more, he felt it, knew it without verbalizing it, to write these things down and to speak them out would calm his troubled mind. It had been near impossible for him to look at Egan this morning. Perhaps he would tell Egan his dream. Not explicitly, generally. Egan had lady problems too. They all knew that even if no one said it. It would be easy to talk to him.

“Ssssssttt. Jax.”

“Here, L-T.”

“How you doing, Little Brother?” Brooks asked. It was going to be harder than he had thought.

“Like a uncorked jug upside-down. Drained, Man.”

“You’ve already heard?”

“Right on.”

“How do you feel about it?”

“Doan mean nothin,” Jax said softly. “Only yo din’t have ta do it like that. I never thought yo do it like that. Yo aint one a em.”

“Jax, it’s my time to go.”

“That aint it, L-T. Shee-it. Yo owe it to yerself. I’s happy fo yo but I aint believin yo din’t know. Jest spring it on us like locust attackin.”

“I’m sorry, Jax,” Brooks said. Jax sounded very depressed and it saddened Brooks.

“Who gowin get the company?” Jax asked. “Yo aint gowin give it to that mothafucken honky Thomaston, is yo?”

“That’s not my decision. The GreenMan decides that. Thomaston’s pretty good though.”

“That honky fucka doan know his weapon from his ass wid out Eg point it out to’m. An Eg leavin in two weeks. We gowin get our asses kicked seven ways ta hell.”

“Jax, it’s going to work out.” Brooks felt a little disgusted. Goddamn, he had the right to leave. “Hey, what are you going to do?” Brooks shrugged and tried to sound carefree.

“Gowin start a war,” Jax said very factually.

“No, Jax. Now listen. You’ll lose everything you ever worked for if you do that.”

“Aint gowin miss somethin I aint never had.”

Doc and El Paso approached Jax’ perimeter position, whispered the password and came forward. They sat, one to each side of Jax and the L-T, and aimed their weapons outward. “Doc,” Brooks whispered, “when I’m gone I want you to keep an eye on Jax here. Watch over him, okay? El Paso, you too.”

“He okay,” Doc said. “He’ll be watchin over us. What’s happenin, Jackson?”

“War,” Jax said. “War in our homeland.”

“Can’t fight with that,” Doc said.

“You guys be careful, huh? Please.” Brooks pulled out his notebook. “Hey,” he said. “I want to give you guys my address. Look me up when you get back.” He wrote his name and address several times and tore the bottom from the page. “Here,” he said. “Give me your addresses too.”

“There aint gowin be no address when I get back,” Jax said. “I’s gowin be roamin. Sabotagin. Blowin up the cities, creatin terror. We gowin hold a million people hostage. Trade their lives for King Richard’s.”

“Take the countryside first,” El Paso said. “Then the cities’ll fall.”

“Not this time, Bro. We got the cities already. We jest gowin hafta squeeze. Then the country’ll fall.”

“What about your kid, Jax?” Brooks said softly.

“I’m gowin do it fo my kid!” Jax snapped emphatically. “Whut yo think I’s talkin bout?”

Egan and Cherry slid into the thicket beside El Paso. The vegetation was so dense they could not see Doc on the other end. Doc rolled to his knees and crawled to the other end. He exchanged abbreviated daps with Egan and Cherry. “Jax pissed about L-T skyin,” Doc whispered.

“They killin our fucken people, they killin Pap, and they takin the best man away from me,” Jax continued. He launched into a quiet tirade of name calling and complaints. He quoted Eldridge Cleaver, “The oppressor has no right which the oppressed is bound to respect.” And he added his own invectives.

“They all a time inventin programs to help minorities which all a time helps keep em down. You hear bout affirmative action. I got affirmative action. Right here in my 16.”

“What do you think about all this, Danny?” Brooks asked Egan. Egan shrugged and said nothing. He did not want to get into it.

“What about you, Doc?” Brooks asked.

Doc shook his head. He looked at Egan. Egan always had something to say. “Doan you care about us no mo, Eg?” Doc said.

“What?”

“Doan you care about Jax no mo? We gotta hear from you. L-T leavin. We gonna be lookin to you ta carry us inta the new honcho. Keep him cool. You dig, Mista? You always got somethin ta say cause you always sayin somethin. What you think?”

“Well, I think there are alternatives to racially administered programs or racially interpreted legislation. And I think they might be more effective because they won’t stink and there won’t be any racial backlash.” Brooks was listening intently to Egan. He began to take notes on his steno pad. Jax glared at Egan, looked at the L-T unsure, interested. Egan continued. “We might call it communityism or something. We could base the action taken to equalize opportunities on communities and not on race. Each community might be defined as this thousand or maybe twenty-five hundred people, no larger. That way it couldn’t be corrupted like if you had one community for a city of one hundred thousand or something.”

“That’s an interesting idea, Danny,” Brooks said.

“Yeah,” Egan agreed. “It could get around all the racism bullshit. You know, why should a black doctor’s kid have preference in a job or in getting admitted to school or something over a white laborer’s kid. That’s not the problem we’re trying to solve. I think if a poor community, and there’d be lots that’d be all black or all Chicano or all Indian or something, if they were treated specially so the poor did not stay poor, the whole idea of equalizing opportunity, ah, hum … what am I trying ta say? You know, you could break the poor produce poor and the illiterate produce illiterate syndrome. And that’s what we’re trying to do. Break down the ghettos but not because they are race ghettos, because they are jails which imprison people and don’t let them get out. Let’s make sure everyone who wants to get out has the opportunity to get out but not simply because they are black. And don’t nobody stress race so there’d be no backlash and no hate. Poor could be mixed with rich and vice versa by busing or somethin. But not blacks with whites simply because blacks are black and whites are white. That only keeps the emphasis on race. It institutionalizes race and it institutionalizes the ghettos. That shit keeps blacks down no matter how many programs you got.”

Alpha moved out of the bamboo thicket, across paths, trails, roads. They moved generally south, generally up, ascending toward a knoll on the side of Hill 636. FO called in a random pattern artillery barrage in the path of their advance, clearing their way, and a sweep of rounds exploding in the trail behind them to close off their rear. They moved slowly, climbed cautiously yet steadily. Under no circumstance did the L-T or any of them want to delay resupply. They pushed on without stopping. They crossed through elephant grass and into brush. Over the mounds they went and to the base of the cliffs. They were two kilometers farther east in the valley than they had been on their original descent. The cliffs here were bluffs and with their half-empty rucks they climbed easily. With each step up the fog thinned, each foot higher the sky lightened. The scrub brush became jungle forest and suddenly the pointman was blinded by the bright searing sun. Alpha rose like a column of dead out of the mist and into the sun-dappled jungle. Like moles the boonierats squinted, blinded by the sun. And then they were there, on a large vegetated hump on the side of 636. They worked like madmen, two platoons on security, one chopping, slashing with machetes, clearing an LZ. A bird, the first unfogged view of a helicopter in many days, passed over, returned, hovered, kicked out two cases of TNT and left. The demo crew set about blowing the larger trees down. “Cheap fuckers,” the demo team members cussed, “dynamite stead a C-4. Shee-it.” Then, “Fire-in-the-hole. Fireinthehole … fireinthe-hoooo …”

Cherry looked around at the men he had been with. Their eyes were hollow, haunted. The weariness of the valley showed on their skin, their drawn cheeks, mostly in their eyes. Could I possibly look that bad? he thought. No way, Breeze. No way.

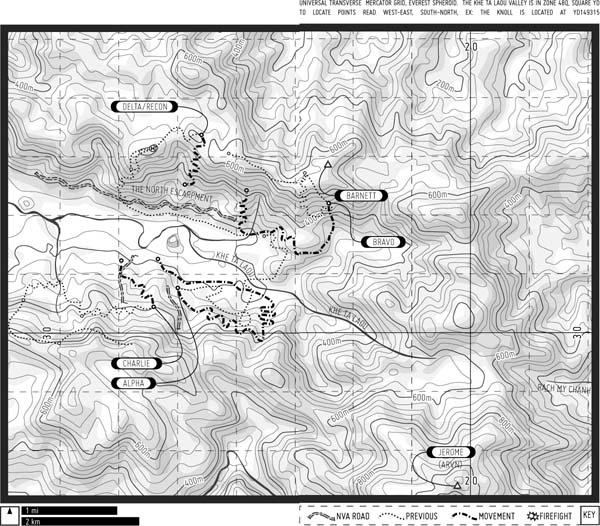

The sun seared and dried the newly exposed jungle floor and the surface turned to dust. The boonierats stripped off their shirts to expose their skin and it too dried, flaked and peeled. In the jungle the security teams hung their fatigues on branches and opened their rucks and spread their equipment. The sun filtered through the canopy and the dancing shadows accentuated the gaunt faces, the ghoulish stares which possessed half of Alpha. Brooks sat alone below the LZ workers, above the perimeter guards, sat alone obsessed with the view of the valley before him. Marshmallow Lake, he thought. It looks like a marshmallow lake. From above the mist again looked soft and clean and white yet it was not beautiful anymore. It was ugly. Brooks glared at the valley, at the rising cliffs and at the ridges and fingers, at the gorges and the undulating foothill mounds all hidden beneath triple canopy. Brooks snarled at the valley floor cloaked by bamboo forests and elephant grass and that blessed terrible ever-present mist. Entire NVA divisions were concealed in those landforms. Enemy, enemy everywhere. Perhaps the valley itself was a malicious adversary. And there in the middle above the mist ugliness, above it all, alone, stood that immense tree. Brooks sat still, hypnotized by the tree. He cursed it in his mind. What must be at the tree’s base? Brooks removed the topo map of the valley from the large pocket on his fatigue pant thigh. He traced the river, located various high features and aligned the tree. There, right there, he thought, right there on the river. On a knoll on the river. All signs, all intuition pulled him toward the knoll and the tree. That was his mission. Alpha had circumvented the knoll on their first descent into the valley, now they would spiral back down, in tighter. Seize the knoll. Why not? Why not just go direct? Why not walk right up to it? Follow an arty raid on in. No. One more time around. One more time through Leech Row. Then we’ll cross the river and hit it.

“L-T,” Doc Johnson approached the commander from the LZ.

“Hey,” Brooks called up, coming from his trance.

“Dry em out.”

“What?”

“Let me see your feet,” Doc said. “Take off them boots.” Doc did not raise his voice but he spoke with absolute authority. Brooks grumbled as he unlaced first one boot, then the other. “Socks too,” Doc said. “We got trouble.”

Brooks peeled his OD issue socks from his ankles and feet as if they were a second skin. “Uuuumm,” he groaned. He wiggled his toes. The skin was gray and ulcerated.

Doc grabbed one of the L-T’s feet and inspected it. Brooks winced. “You lucky you ken walk, Mista,” Doc said disgustedly. “Half your company sufferin from immersion foot. You expectin these dudes ta walk any place you best get em dried out.”

Brooks stood up barefoot and twisted in small spasms of agony as twigs ripped at the soft convoluted flesh of his feet. “Let’s inspect them all,” he said to Doc and the two set off on a slow circuit of the perimeter inspecting that prize asset of the infantry—feet.

Half the company was suffering from the onset of immersion foot. Doc and the L-T looked at foot after foot. Every foot was wrinkled and gray. A quarter of Alpha’s feet were swollen. A tenth had progressed to being convoluted. The two worst cases, both in 3d Plt, were Arasim in 2d Sqd and Roseville in 3d. With both of these men the immersion foot had progressed to the point where the skin cracked and fungal infections had begun. The outer skin layer of Roseville’s left foot had completely died and was peeling off in putrid chunks. Below, the tissue was raw.

“Evac those two,” Brooks agreed with Doc. “Get them out of here on the first log bird.” Arasim was delighted. He was packed in a minute.

On the opposite side of the perimeter Whiteboy was also all packed and ready to leave. His eye was worse than it had been when originally cut. The eye watered constantly now and Whiteboy said it felt …” lahk someone throwed a shovel full a ground glass in theah.”

“Whiteboy,” Brooks said, “do you really feel like I should medevac you? We need your firepower.”

“L-T, Ah caint keep mah eye open.”

“Really?”

“L-T, Ah’d stay out heah. Haven’t Ah always done mah part? Ah’ll be back, L-T, in no time a’tall.”

“Okay, get up to the LZ with Roseville. But listen, we do need you. Get back as soon as possible. Okay?”

“Yes Sir, L-T.”

Brooks completed the circuit and sat down again below the LZ. How, he thought, can I tell a man to get back here as soon as possible, that we need him, when I’m leaving? About him now half his company was not only barefoot but naked. To his left Cherry lay in the sun, his pants at his ankles. His legs spread wide apart, his penis flopped up upon his belly, his red raw thighs, burning ass and crotch rot drying and baking in the sun.

“Hey,” Brooks called to Cherry. Cherry looked over. They were not cautious about noise. What with the machete hacking and the blowing down of trees, everyone in the valley knew exactly where Alpha was. With the LZ completed much of Alpha was in the open. They knew it was unlikely the NVA would hit them. The sky was full of helicopters and FAC planes. Ownership of the night may have been in dispute but the day very much belonged to the Screaming Eagles. The perimeter guards still camouflaged themselves. There were three two-man OPs hidden 100 meters out. The security guards rotated hourly with soldiers loafing about the LZ. The slicks which were to resupply them at 1100 hours had been called off for an emergency CA of ARVN infantry nine kilometers to the south. Resupply was rescheduled for 1330 hours. Alpha lay back in the sun.

“Hey,” Brooks said again getting up and reseating himself a few feet from Cherry. “Several weeks back we were talking about war and you said something about it being biologically determined. Would you tell me something about it?”

Cherry twisted his body to look at the L-T while keeping his legs spread for the sun. “Yeah, I guess,” he said. “What kind a thing did you want to hear?”

“You know,” Brooks said not looking at Cherry, “theories maybe. Are there biological theories about war?”

“Yeah, sure,” Cherry said. “Kinda.” His mind had been far from biological theories.

“You’re a biologist, aren’t you?”

“No,” Cherry said. He sat up yet still kept his legs open to the sun. “I got a BA in psych.”

“Where’s the biology come in?”

“I did a lot of reading and research into physiological correlates to behavior,” Cherry said. “After I decided to go into psych I found I thought most of it was bullshit. Almost all of it except the material based on neurological or physiological data.”

“Oh,” Brooks said. He was disappointed.

“But wait a minute,” Cherry said. He wanted to tell Brooks his views. Cherry felt eager to impress the L-T and talking, thinking about his subject brought him a step back toward reality, toward a world he was quickly forgetting. “Ya see, L-T, what you’re talking about is behavior, human behavior. That’s the realm of psychology. It’s just that so much of psychology has been individual conjecture that it turned me off. There are physiological correlates to all behavior. When I was a student my interests were about what happens in the central nervous system when a person does something, or what happens there before he does something. What makes him do it, behave? War is a kind of behavior.”

Brooks changed his position and became more attentive. “Are there books on the biological, ah, on psychological or physiological, ah … connected to war?”

“Well … well there are some.” Cherry hesitated. “Not exactly like that but.… well … you might want to read The Territorial Imperative. I forget who it’s by.”

“Wait a minute.” Brooks pulled a ballpoint from his pocket and the steno pad from his pants. “The … Territorial … Imperative,” he said slowly writing the name down.

“Yeah, and ah, African Genesis,” Cherry added. “I’m sure they both contain bibliographies.”

“Good,” Brooks said.

“L-T, the crux of their position is that man is an animal. It gets a little complicated but it’s possible to extrapolate from the known data to relatively sophisticated ideas or maybe theories, hypotheses anyway, about war.”

“Tell me more,” Brooks said moving closer.

“Okay,” Cherry said settling back and attempting to recall segments of his formal education. Brooks was poised to take notes. “I’m goina throw some facts and figures to start with to help me think. Okay?”

“Yeah. Okay.”

“Okay. First, mankind is like three million years old. Maybe older. He’s been evolving the whole time.” Cherry frowned, paused, rolled to his side and continued. “Man a long time back was a hunter. As an animal he either hunted game or he gathered food. He didn’t cultivate crops or raise animals for slaughter until something like ten or fifteen thousand years ago. Long time back he had a very tiny brain. Try to picture these pre-men men. They lived in small packs and hunted. They ran game. And they were evolving. But during evolution they never lost their hunterbrain. Instead, what happened was, they developed new layers over the old brain. Not really layers like you’d pack a snowball or something but like you’d take a snowball then add another ball to it here, and another there and over hundreds of generations the new balls became larger and larger and wrapped themselves about the original ball which we’ll call the brain stem. Can you see that?” Cherry began sketching his image in the earth.

“Okay,” Brooks said. “So?”

“Well,” Cherry jumped the conversation forward, “these two balls are the neocortex. They’re maybe five hundred thousand years old. Now it’s been shown through neurological experiments and … ah, there’s another guy you should read, Wilder Penfield. I think one of his books was something like Mechanisms of the Brain. Something like that. He and others did a lot of work on functional mapping of the brain. Do you know what that means?”

“Like separating the brain into parts by function?”

“Yeah. Exactly,” Cherry smiled. “Into functional areas instead of anatomical parts. For example they found that there is a specific area for reading, another for memory of words while you’re reading. There’s an area for writing which has its own word memory area which is why a person’s vocabulary for reading or writing or speaking is all different. There are specific areas for specific motor movements. Specific areas for things even as specific as remembering a tune. There are mechanisms for integrating memory with new information being received to form concepts. The way our neural pathways are structured has a lot to do with the way we think or behave.”

“That’s fascinating,” Brooks said. He was taking sketchy notes. A word here or there.

“Wait a minute,” Cherry said. “I’ll get back to this but first let me say that emotions, fear, aggressive behavior, territorial behavior, the strong emotions, they seem to be located in the brain stem or are at least activated by stimulating the brain stem. The higher cortex is the location of abstract thought and complex concepts and planning and worry. Stuff like that.” Cherry was becoming wound up. It was like taking his oral comprehensive examinations prior to graduating from college except that this time it was fun. He was surprised at the avalanche of thoughts and facts, of figures and ideas that crashed down upon his speech center all trying to be communicated to the L-T at one moment. “You see,” Cherry said, “our brains are built on an ancient brain stem and our brain stem dates back to when we were animals, maybe back to when we were reptiles. You can’t understand human behavior in the present without looking at man’s evolutionary history. We were built, muscles, heart, skeleton, maybe mind, to run or to attack. Physiologically we want to do these things. We bring a lot of our past to the present in the anatomical and functional makeup of our bodies and brains. Humans were aggressive territorial animals. We still are today but now we’re more refined and we’re capable of building and using helicopters and fighter-bombers to express our ancient physiological emotions.”

Brooks was now writing feverishly. It was a new approach for him and it fit in with his other beliefs about war. The concept excited him. He put to the back of his mind the LZ and the valley and everything else about him. There was something significant in what Cherry was saying. Something that went deeper than even Cherry knew.

“The brain stem still functions,” Cherry began again when the L-T’s pen slowed. “When people are under stress they revert or regress to earlier forms of behavior. The neocortex is, ah, the brain kind of short circuits and bypasses the neocortex. Let me back up a moment. I said before physiologically we want to run. It’s more basic than that. The most basic need of any organism, the most basic drive, is for stimulation or information from its environment. That’s what’s behind man’s drive to explore the reaches of space. If we want to understand the complex behaviors, first we have to understand the most basic, and that is the drive to acquire information from the environment. The acquisition may be equated with stimulation, so it may be said that man requires or has a drive for stimulation. Follow that to its extreme, daredevil sports are almost maximum stimulation. The only thing more stimulating is war.”

“That seems a bit farfetched,” Brooks said.

“Maybe,” Cherry said. “Maybe the last part but in combination with our evolutionary makeup, the idea of a drive for stimulation and the fact that if we’re stimulated in a stressful way we’ll regress to our animal instincts … see? Combined, they push us to fight.”

“Hmm. Yeah,” Brooks said cautiously. He found it easy to accept Cherry’s statements but difficult to accept his conclusions. “I’m not sure …” Brooks began.

“We should have a course on bio-knowledge or bio-culture,” Cherry interrupted him. “One of the questions no one’s been able to answer is how much information we’re born with. How much of our present do we organize because of information we possess within our cells? In our DNA or RNA? How much knowledge is passed genetically from generation to generation?”

“Hum,” Brooks mused. “If that were true …”

“Yeah,” Cherry said. “Do you know there have been birds hatched in incubators and raised completely alone and yet in a planetarium these birds can navigate the course they’ve got to fly to migrate with their species? It’s as if they have a complete map of the stars in their genetic structure and a complete understanding of how to use it. They don’t learn it. They’re born with it. How much knowledge do you think man’s born with?”

“If that’s true,” Brooks said quickly trying to get a word in edgewise, “I wonder if different races maybe have slightly different organizations of their brain structures and maybe even of the information passed from …”

“It’s true,” Cherry said. He was feeling very good.

“Hey,” Brooks said softly, “talking about evolution, there’s physical evolution and there’s also cultural evolution.”

“I’m not sure I understand.”

“Well, a culture passes knowledge from one generation to the next and that body of information grows. The culture evolves to a higher form, a more complex society.”

“Yeah, of course.”

“I’ve got some questions,” Brooks said. “Why must every man make the same mistakes in his life that his father and his grandfather made in theirs? Why must every generation have its war? Each year our weapons systems evolve to a higher and higher state but mankind just repeats itself again and again and all the time with larger weapons and with larger consequences. Why can’t the mind of man evolve?”

“It does, L-T. Well …” Cherry stopped. He was thinking that it does because of the higher layers and that it doesn’t because the brain stem continues to repeat itself. Cherry’s face contorted and showed his conflicting thoughts. “Evolution isn’t really clean,” he said finally. “Like, did you know that Neanderthal man had a larger brain than present-day man. Anthropologists say that we have superior verbal abilities but maybe he just didn’t … ah … maybe he lost his brain stem. Like he wasn’t aggressive enough. Homo sapiens destroyed him.”

“Maybe we talked him to death,” Brooks laughed. Cherry laughed too. The two of them talked on and on as Alpha dried out, rested, rejuvenated.

Brooks continued taking notes. He was skeptical but now was the time to find ideas—later he could validate or discard them. At one point he wrote: It would be arrogant to believe that man is the last creature of creation. Will the Creator stop here or will He create something superior to us? Brooks read that to Cherry to get his reaction.

Cherry looked at him oddly then said, “God created man in his own image. Then God became man. Do you know why? It’s because Man is God.”

At 1330 hours El Paso and Doc interrupted the conversation telling them the log birds would be on station in one five.

The first resupply bird delivered what Alpha had come to call the très bien resupply. Doc had heard Minh use the term and he thought it was Vietnamese for ‘Three Bs’ as in beans, bullets and batteries. Jax had picked it up from Doc and from those two it had spread and become universal company jargon. With the très bien resupply, amongst the cases of C-rats, ammunition and radio batteries packed onto the helicopter, was Spec 4 Molino.

“Hey Man,” Molino screamed to Whiteboy, the two passing in the roar of the helicopter rotorwash, “they stickin it ta me, too.”

Then the bird and Whiteboy, Arasim and Roseville were gone. Molino stood on the silent LZ in starched, tailored REMF fatigues. He squinted at the Alpha troops near him. He stood stock-still shocked. He had seen them all on stand-down only eight days past. They had been drunk and cheerful and healthy-looking. They had transformed to vacant shells, to wraiths, to apparitions. Yet they did not know it. They lugged cases of Crats off the LZ and broke them down, they cleaned their weapons, they resolutely worked at their tasks, attempting to appear like living soldiers. On all of them Molino saw death. He shuddered.

“Hey, Egan,” Molino called spotting the barefoot platoon sergeant in the shade of a palm frond lean-to.

Egan looked at him. “Three Buds and three Millers,” he mocked.

“Comin right up,” Molino laughed. He could not keep his eyes on Egan. Egan’s feet were gray and smelled dead, even at ten paces. Scabs and sores crusted his arms. His lips were cracked, blistered, peeling. “Hey, the Murf was by. He come over the other day to see ya.”

“Fuckin Murf,” Egan smiled. “How he doin?”

“Man, he couldn’t believe you went back out. Man, he said ta tell ya about Mama-san. Said, Man, that you’d wanta know.”

“Which mama-san?” Egan snarled suspiciously.

“You know, Man. The one the Murf always goes up to.”

“What about Mama-san?” Egan asked.

“She been blown away, Man. She an three of her gook kids. All her daughters, I think. They tryina say the VC done it but the Murf thinks it was GIs. Some dude the old bitch fucked. Maybe give him some bad dew … Hey, where ya goin, Man?”

To Molino, El Paso looked much healthier than Egan. Tough brown skin, Molino thought, like Dago skin. The ex-bartender/ librarian cornered the barefoot senior RTO in amongst the CP’s ruck pile. “Hey, “¿que pasa, Senor?”

“You are, Bro,” El Paso said quietly.

“I brought ya somethin, Man,” Molino said. He slipped his shoulders and arms from the unfamiliar straps of his ruck and let the weight crash to the ground. “Fucken things,” he cussed. He dug through the jumbled contents and pulled out a thick paperback. “Here,” he said handing El Paso the book. It was a copy of Vietnam: A Political History by Joseph Buttinger. “It come in just before the GreenMan stuck it to me,” Molino explained. “I know you read this stuff so I checked it out for ya.”

“Well,” El Paso said accepting the book, “check it out, Bro. Check … It … Out! Thanks.”

“Yeah, I was sure you’d want it.”

“Hmm,” El Paso moaned reading the backcover then the table of contents.

“Hey,” Molino said trying to maintain a mellowcool voice, “this … they say this is a bad AO.”

“Could be worse,” El Paso said detached, leafing through the book.

“Gotta be a bad AO. They tell me Rapper Rafe got clean scattered to the breeze.”

“You mean Ridgefield?”

“They said you couldn’t even find his chest or arms and that you guys just put the pieces in a bodybag.”

“I wasn’t there,” El Paso said eyeing Molino. Molino was staring off toward the valley. “I wasn’t there but that’s not how it happened. Sniper got him. Only one round. Maybe two.”

“That’s not what I heard,” Molino said lowly. “Shit. Him an Escalato in the same week. That’s fucked, Man.”

“Yeah, it’s fucked,” El Paso agreed matter-of-factly.

“No fuckin way I wanted to come out here, Man,” Molino said. El Paso did not answer. “Don’t nobody expect me to accept my own execution. That’s for fools and Mama didn’t raise no fools. I’m gonna fight it every mothafuckin step of the way. You’d do that, right?”

“Yeah,” El Paso said.

“Hey,” Molino said. “Hey Bro, would you do me a favor?”

“What do ya need?”

“Oh, it’s nothin, Man. Maybe I shouldn’t even ask.” Molino squirmed pretending discomfort.

“What is it?”

“Well, I.… ah.… I was wonderin … ah … if you could, you know …”

“Know what, Man,” El Paso let him squirm.

“If you could talk to the L-T, Bro,” Molino pleaded. “I’d like to get inta the CP. Man, I can’t even picture myself down with a squad. I’d probably get half of em killed if I ever had ta walk point.”

“Naw, you’d be good, Bro.” El Paso smiled to himself. “Es verdad. I know. You are a cagey person. You’d be very good to have at point.”

“Oh no, no, no. Not me Bro. Hey … ah … I’m … ah … outa practice at that sort’a thing. Bro, I know you could set it up for me. Man, I’d hump yer books if you get me into the CP.”

“Ah, my friend …”

“El Paso,” Molino was becoming frantic, “I’ll hump yer batteries.” El Paso looked down and shook his head. “Man, yer water. That’s half the weight of yer ruck.”

“I caint do, my friend,” El Paso said sliding into a deep chicano accent. He threw up his hands. “L-T, he say, send Molino to Mohnsen. You go there. 2d Sqd, 2d Platoon. There, there is only Mohnsen and Sklar left. You caint kill half a squad when there are only three people.”

The GreenMan burst upon Alpha bringing more enthusiasm than Alpha’s ascension to the sun. Along with his radiant smile and praise he brought dry cigarettes and lighters, bug repellent, foot powder and a crate of XM-203s. He also had with him the battalion executive officer, Major Hellman, and Command Sergeant Major Zarnochuk. He had ordered them both to smile. All three looked pink against the grayness of Alpha. Pink and clean and spit-shined.

“Lieutenant,” the GreenMan’s voice was clear and strong, “you’re doing one helluva fine job. One helluva fine job. You and your men have been wreaking havoc down there.” The GreenMan raised his voice so the entire LZ crew could not help but hear him. “Your kind of success calls for rewards,” the commander beamed, “and I’ve got a bunch coming your way. Major. Break out that first box. We’ll get to the other one later.”

Half a dozen troops had approached to a respectful distance. They squeezed closer. The GreenMan played to his audience. Major Hellman bent over slowly. He slit the cardboard with his knife and peeled back the lid. The GreenMan stepped forward. His eyes twinkled like a boy playing ringmaster beneath the big top. He reached into the box and pulled out five shiny chrome Zippo lighters and he tossed them to the infantrymen standing, staring, acting no different from the Vietnamese peasant children when they themselves tossed cigarettes or gum to the kids in a ville.

“Oh wow, Man! Look at this,” the children-soldiers squealed. The lighters were engraved on one side with a map of Vietnam and on the other:

BOONIERAT

A/7/402

101ST AIRBORNE

AUGUST ’70

WAS A BITCH.

“There’s one for every man here,” the GreenMan beamed.

“Let’s keep this orderly,” Brooks said as a second half dozen soldiers clustered forward. “El Paso. Call the platoons. Have them send up one man from each squad for the lighters and cigarettes.” Brooks bent and grabbed a lighter and smiled. The Zippo had a nice feel, a nice heft. “Thank you Sir,” he said to the GreenMan and the GreenMan beamed brighter. In minutes every Alpha troop was smoking a firm dry cigarette lit with his new Zippo.

Then the smiles stopped. At one end of the LZ Old Zarno cussed out Jax for the hair pic stuck in his growing fuzzy ‘fro. Hellman indiscreetly jumped on a sleepy FO for the sloppy example the forward observer was setting. FO was naked, “… in full view of enlisted troops.” The GreenMan shook his head and hustled Brooks away from everyone with a ‘Let’s-have-a-look-around’ gesture.

“Tell me about Delta,” the GreenMan said when they were alone. “How were they set up? What were they doing when you were there? How did they act? Were they quiet?”

Brooks told him what he and the others had observed. The GreenMan seemed concerned, sincerely concerned and hurt. “How am I supposed to help these men?” the GreenMan whispered. “Lieutenant, if no one informs me about how badly one of my units is performing, I cannot correct it. That was a massacre, Lieutenant. And I’ve half a mind to have you court-martialed for not reporting O’Hare’s incompetence to me.” The GreenMan did not speak in anger. Not yet. He seemed very saddened by the event at Delta two nights previous. Then he burst out, “What the fuck was the motherfucker doing?” The GreenMan cussed like a trooper. “That sadass got his fucking self and five others killed. Seventeen wounded. If he hadn’t got himself killed, I’d of killed him myself.” He paused to take several deep breaths. Brooks had never seen the GreenMan upset. “Lieutenant, a lot of people in America are screaming about our ground forces still pursuing the enemy.” The GreenMan’s voice became bitter. “They’re asking why we don’t stay in our bases and let them come to us. Those people do not understand the first thing about war. If we sit in fixed defensive installations they’d murder us all in three months. We must constantly be searching for the enemy, finding him, hitting him before he can hit us. The moment we set up, the NVA moves. If we do not pursue he can resupply at will, advance at will. He can choose the time, the place, the method of attack. That’s why we’re out here. If you set up some hideous semi-permanent base here, like O’Hare, I promise you, the enemy will know and he will maul you. Get these men moving. Keep them moving. All my companies will be moving.

“That Delta thing, that was strictly a leadership failure,” the Green-Man continued. “Lieutenant, O’Hare failed his men. Perhaps I failed O’Hare. I’m not going to fail you. You,” the GreenMan called to a troop they were passing as they walked, “come here.” Cherry approached the colonel. He was not sure if he should salute or not. “Why hasn’t this man shaved?” the GreenMan growled at Brooks. “Look at his rucksack. It’s filthy. A mess like that makes enough noise to let the entire valley know where you are. Get that man squared away. Lieutenant, follow me. I want to inspect every one of your troops.”

Cherry sighed soundlessly watching the GreenMan stomp off.

“This entire battalion’s too fat, too lazy.” the GreenMan was now ranting with anger. “This is the 101st. This is SKYHAWKS, Seventh of the Four-oh-Deuce. I’ve stripped every possible man from the rear. You got Molino, that worthless candyass. Running a goddamned club when there’s nobody in the rear except clerks and jerks. I’ve sent nine men to Delta, three to Bravo. All the cooks are on Barnett. We’re going to leanout this unit, Lieutenant. Every able-bodied man in the bush. You have two men in the rear on charges, don’t you?”

“No Sir. That’s another company.”

“If you get any, they can wait for their trials out here.”

“Yes Sir.”

“I need leaders, Lieutenant. Any officer who can’t do the job is … is not going to be transferred. He’s going to become a rifleman. I’ll make sergeants acting platoon leaders before I’ll let a piss-poor lieutenant kill any of my men. If you have problems with your leaders, let me know. Right now. We’ll shuffle them around this afternoon. I’ve got the authority to do that. What do you need?”

The GreenMan’s rage had taken Brooks by surprise. “Nothing, Sir,” he said without thinking.

As they passed through the 3d Plt CP set-up the GreenMan switched back to his sales manager voice. “Rufus,” he said, “I’m impressed with your moves so far. I think Alpha is doing a fantastic job. Truly fantastic. I know you’ve been plagued by the weather but the intelligence information alone that you have amassed has been enough to sufficiently alter the balance of force in this valley. The Old Fox said that to me himself. The NVA will never again be able to run through here unmolested.”

The two commanders completed their circuit of the perimeter and were now back beside the LZ. The GreenMan again showed disappointment. He had taken in tremendous detail. As they stood the GreenMan listed every improperly discarded tin can, every unconcealed soldier, every weapon lying on the ground and not ready in the hands of a boonierat. Then they stood in the shade of vine-choked trees and peered into the valley and discussed intelligence reports and tactics. Brooks retold him of Leech Row and of the enemy roads and the thickets and fog. “You go back down there and finish the job, Lieutenant,” the GreenMan said. “You can do it. It won’t take much longer. There’s two less enemy there now than there was this morning. My pilot and I got two on our way over here.”

“Yes Sir. I heard,” Brooks smiled. He paused then said, “Sir, about my request to DEROS …”

“You go back there, Lieutenant. Finish the job and you can go home knowing you left this country safer. You should be able to clean this place up in two or three days. Go back down there, Lieutenant. Become a guerrilla behind the guerrilla lines. Can you do that?”

“Yes Sir,” Brooks said. The GreenMan seemed to be expecting him to say more so he added, “I can hide down there, Sir. In the thickets. Among them. We can pick them apart, piece by piece.”

“Good,” the GreenMan smiled. He was satisfied. “Follow me,” he beamed loudly marching to the unopened crate he had brought to the LZ with the cigarettes and lighters. “Break that one open, Major. Lieutenant, bring up all your thumpermen.”

Major Hellman broke open the crate and lifted from it the first new XM-203. The XM-203 was a replacement for the M-79. It was an over/under, an M-16 rifle on top mated to an M-79 grenade launcher on the bottom, all on an M-16 stock. Hellman handed one to Old Zarno then reached in and lifted another. “Look at these beauties,” he said smiling. And indeed the men who received them considered them beauties.

“You’ll be a one man army with that,” the GreenMan said to one smiling troop. “What’s your name?”

“Willis, Sir,” Numbnuts said smartly snapping the new weapon to his shoulder.

“That’s the first one of its kind in all I Corps,” the GreenMan said to Numbnuts. “You’ve got the first, Alpha’s got the first nine.” The sound of the C & C bird could be heard as it approached Alpha’s location. “Good luck with those,” the GreenMan beamed to all of the company’s thumpermen. “And good hunting.” The C & C bird hovered, set down. The GreenMan saluted Brooks. “Find em. Fix em. Fight em. Finish em. For the glory of the Infantry, Lieutenant.”

Brooks returned the salute. “SKYHAWKS, Sir,” he said sharply.

The third bird in brought mail, clothes, two members of the 7/402 battalion kitchen staff and mermite cans of Kool-Aid and chipped beef.

“What the fuck is this?” Molino moaned to Mohnsen when the kitchen orderly slopped a ladleful of the brownred mush atop a soggy piece of toast and handed it to him on a paper plate.

“What the fuck do you care?” the orderly laughed.

“It aint Cs,” Mohnsen smiled.

“Shit-on-a-shingle,” Molino shook his head. “Christ, last time we had this was when Zarno threw that correspondent out of the mess hall.”

“What correspondent?” De Barti asked from behind Molino.

“Didn’t you guys hear?” Molino asked.

“Naw,” said Calhoun. “We never hear nothin.”

“That dude, Caribski,” Molino laughed. “Lamonte brought him down to battalion mess. You shoulda seen Zarno. He turned red as a beet. Begins screamin at this guy. Ya know, this dude’s got muttonchop sideburns and hair about this long.” Molino motioned with his hand just above his shoulder. “‘Get outa here,’ Zarno screams. ‘We don’t want no bums in our mess hall. Get out.’ I mean Zarno’s screamin at him. PIO is there tryin ta calm Zarno down. ‘Sergeant Major,’ he says, ‘this man is a civilian news correspondent.’ ‘I don’t give a shit,’ Zarno yells. ‘Get that long-haired hippie bum outa my mess hall.’ I thought Zarno was goina hit him. Instead he shoves Lamonte. You shoulda seen it.”

“Well, what happened?” Mohnsen asked. Five of them had worked their way through the chow line and now sat clustered in the sun on the LZ.

“The guy got up and left,” Molino laughed. “He got up and walked out and everybody got up and gave him a standing ovation. Man, you shoulda seen Zarno. His whole face turned purple. I thought he’d blow a blood vessel right there on the spot.”

“Man, I wish I was there,” Calhoun said.

“What for?” De Barti laughed. “This food’s worse than Cs.” They all laughed.

“You know what they do at division?” Molino said. He was enjoying being the center of attention.

“Tell us, Man,” Mohnsen said. Mohnsen had clung to Molino ever since the ex-bartender had been assigned to him. Molino somehow filled the vacancies in Mohnsen’s mind, the vacancies of the dead and wounded from his squad.

“Man, you wouldn’t believe it,” Molino said. “But I shit you not, this is the God’s honest truth.”

“Come on,” De Barti prodded him.

“You know,” Molino said, “like at the general’s mess. He has, like, thirty people to dinner every night.”

“Bet they don’t eat this shit,” Hayes laughed.

“Man, like they eat steak or lobster tail every night. Every night, Man. They get a choice of three entrees. And, they get served immediately. Steak, lobster tails and one other every night. Rabbit or chicken or duck. That’s the third. You know how they do it?”

“Oh wow. I wish I could eat there just one night a month,” Calhoun said.

“How?” De Barti asked.

“You know how they can serve everybody immediately?”

“How?”

“They cook up three times as many entrees as people they got comin. Then if everybody orders lobster they got thirty lobsters cooked up. They dump the rest of it.”

“Naw. No way.”

“I shit you not. Dudes on KP got it set up so they always throw the leftover entrees inta one garbage can. Then at night the dudes from the headquarters companies, they sneak down and eat the general’s garbage.”

“Mail for Choo-lee-nee,” El Paso called out as he came toward 1st Plt. “Sorry, Bro,” he whispered to Egan. “Nother letter for Choo-lee-nee. Nother letter for Choo-lee-nee. Oooo! This one smells nice. Postcard for Choo-lee-nee.”

Cherry blushed. A postcard and three letters. Half the mail for 1st Plt and all for him. El Paso read the card aloud. “‘Dear Jimmy, We always think of you and I pray for you every night. Uncle Tony said CYA—you’d understand. Much love, Aunt Millie.’ Aaww, aint that sweet! Oooo-ooo! Smell this one.” El Paso handed the letter to Doc McCarthy who sniffed it and passed it to Cherry.

Cherry got up all smiles. He moved a short distance away and opened the letter from Linda. As he began reading he heard El Paso say, “Anyone want Leon’s Newsweek? Here’s some good shit. Listen, ‘… five years of warfare against the US have so badly depleted Viet Cong ranks that today an estimated 75% of the communist troops in main-force units are North Vietnamese … barred by a lack of popular support from reverting entirely to guerrilla warfare, the communists are limited in what they can accomplish …’”

“Hey, El Paso,” Thomaston chuckled. “Who the fuck are the other twenty-five percent?”

Cherry shuffled the pages of Linda’s letter, looked at them for a moment without reading as if the shape or color might tell him what she would say. Then he read.

Hi Jim!

Guess what? I got a new job in downtown Norwalk. I’m a secretary to two men who sold their business about eight years ago and bought a whole bunch of properties which they manage. It’s a real small office—the two owners, a bookkeeper, an accountant and me. I’m the only girl. I know I couldn’t have stood working in a big office with all the catty women so I found something more me. I bet you thought by now I’d be off somewhere carousing, huh? Well, I was a little confused as to what I wanted but things are a little better now. Not that I’m settling in, I’m just content for now.

My sister got engaged about a week ago and is getting married in October. She hardly knows the guy. He isn’t exactly welcomed into the family either but if she wants to marry a darkie (he’s not black, just dark) that’s her business.

My Dad got a new car. It’s white. I already don’t like it because the first time I got into it I hit my head. I’ll probably hold this grudge against it until I smash it up. Dad wants me to get one of my own but I say I don’t need a car. There’s always one available here if I want it.

Oh, what else has happened? I made it to Boston last month and I love it there. If things work out as I hope they will, next January I may take an apartment up there with a friend who goes to college in Boston. I’ll work. I really love Boston. The people are very friendly.

If my money situation works out I’ll have enough for a car and an apartment. My parents won’t say too much. What can they say? If they say no, I’ll go anyway and they know it. I know they wouldn’t hold me back from doing anything. I made it to NYC a few days since you left. I’ve a friend at Columbia, so I stay there for freesies. I don’t really like New York too much, but for a lack of anything else better to do, I go there.

Time out to eat. I’m still a skinny little bitch! One night I went for a ride because I was bored. I stopped at a gas station and asked where I was just out of curiosity. Massachusetts. Nice little ride I had.

Well, Jim, have a happy. I’ll be thinking about you.

Love,

Linda

* * *

“God, Mista. Oh God!” Doc was sobbing.

“What’s the matter, Doc?” Egan asked. They were at the CP. The radio message had arrived just before Egan came up to talk to Brooks about their move back into the valley. “What is it?” Egan asked perplexed. He could not imagine anything that had happened to Alpha or to any of the battalion units that would cause Doc to cry now.

“It’s Whiteboy; Eg. Aw Eg. They got Whiteboy. They got his bird wid a .51 cal, Mista, they done got his mothafucken bird comin outa Barnett. In the chest, Eg. A .51 cal in the chest.”

Egan stopped. Everything in him stopped. He looked at Doc then turned without saying a word and walked away.

Whiteboy had boarded a helicopter on the firebase which would take him to Camp Eagle. The forward supply crew had razzed him about his minor eye wound and he had laughed with them. Then as the bird left the peak and sped down the mountainside an NVA fire team had opened up with a .51 caliber machine gun. Several rounds impacted in the bird doing minor damage. One round hit Whiteboy in the lower left abdomen. The round smashed upward at an angle moving through his diaphragm and stomach, shattering ribs and exiting through his right front chest. It took the helicopter sixteen minutes to have him at the 326th Medical Detachment at Camp Evans. He received immediate aid and was flown to Phu Bai and operated on. He was then evacuated to Da Nang. The next day Clayton Janoff would be evacuated farther, this time to Zama, Japan, where he would die seventeen days after having been wounded.

In late afternoon the back bird arrived to take out the kitchen staff and mermite cans, all the unclaimed food and weapons and anything else Alpha wanted to DX but did not want to fall into enemy hands. The sun was still hot like a white fever blister in the sky. Alpha was packed and ready to move. The LZ was spotless. Brooks had screamed at every troop within range after the GreenMan had left and after the shock of Whiteboy’s wounding had jolted him. “Clean this site,” he had snapped. “I don’t want to see an uncrushed can, a usable piece of cardboard or a usable fighting position. Don’t leave a fucking thing the dinks can use. And if I hear a sound from a soul, every man here’s going to pay.”

And Alpha had cleaned. They cleaned their weapons and themselves and they cleaned the LZ. Even in their filthy ragged fatigues every troop looked sharp. Everything was tightened, trimmed. Ammunition was cleaned, almost polished. Alpha knew it was going to fight. Alpha wanted a fight. And in their fight the last thing they wanted was a weapon jammed with mud-caked ammo. They cleaned with hate, prepared with hatred. Fuck up Whiteboy, huh? Have the colonel yell at our L-T, huh? Well, fuck em. We’ll show em.

Then the back bird arrived. Alpha had received almost no clean fatigues from the company clothes fund during resupply but now they received one-hundred-fifty pair of clean dry boot socks. They had received seventy-five tiny bottles of insect repellent. Now they received two-hundred-fifty bottles more. Doc hustled around distributing the goods and Alpha sat, changed socks and cooled down.

Alpha moved out, up around down, back onto the valley floor. They leap-frogged down and west. 3d Plt led then 2d with the Co CP and finally 1st. As the others left the high ground, 1st Plt dug and chopped pretending to be digging in for the night. 3d Plt moved slowly, in column, through the discontinuous brush and on into thickets of bamboo. They halted and formed a tiny perimeter. 2d Plt followed 3d by twenty minutes. They reached 3d’s position and worked through and beyond by 200 meters. Then they too halted. 1st Plt left the LZ and followed. They moved through 3d, then through 2d and finally beyond, west 200 meters.

During the descent to the valley floor Brooks was plagued with doubt. “Step by step,” he whispered to himself trying to dispel the uncertainty. “Step by step. Down into a tiny hell I struggle to go. May the gods pardon me for leading seventy-five men into this inferno.” Then he stopped whispering and just thought. Why do I do this bidding for others? Why do I ask these soldiers to do bidding for me? Stop it. Don’t question it. Not now. Step by step. Down. One step at a time. One thought at a time. One tree, one blade of elephant grass. An endless progression of life goes before me. One by one. Steps, trees, thoughts, lives.

Twenty minutes after 1st Plt had stopped, 3d rose. 3d leap-frogged 2d then 1st and moved 200 meters beyond. At each set-up Alpha hoped to catch the NVA moving. They spotted no movement. They slipped back under the valley’s mistblanket and the mist sapped the sun’s residual warmth from their bodies. The trail was thickslick mud. The valley stench clogged their throats like sputum in the throat of a derelict. Old fears surrounded them like the mist, dampening their hatred and bravado. They fought the fears.

“Hey, Cherry,” Egan whispered, “aint we about on the 18th hole of yer golf course.”

“Yeah,” Cherry laughed, fidgeted. “I’m goina put the green right under yer ass.”

“You leave my ass alone,” Egan winked. “Play with yer own putter.”

Beneath the mist it had become dark. The platoons continued leapfrogging. Now west, now north. One klick. Two klicks. They were in it deep, in thick vegetation, in enemy territory. The knoll would be only 500 meters north of them. Brooks called a halt. No one made a sound. No one ate. FO radioed in DT and H & I coordinates so quietly that Brown next to him couldn’t hear. And Alpha sat. It became darker.

“Hey, Cherry.” It was Thomaston. “Company’s staying here tonight,” he whispered. “You got LP. Go out—to the north about fifty meters. Take Willis with you.”

“With Numbnuts?!” Cherry blurted.

“Ssshhh. Yeah.”

“No way, Sir.”

“What?”

“No fucken way, Sir.”

“It’s your turn,” Thomaston said.

“I’ll go,” Cherry said, “but if Numbnuts is goin, I aint. No way.”

“What do you mean you’re not going?”

“Hey, that noisy fucker falls asleep every night,” Cherry whispered.

“I do not,” Numbnuts’ voice came from behind Thomaston.

“I aint goin with him,” Cherry said firmly but quietly.

“I didn’t fall asleep that night …” Numbnuts began then his voice muffled and Cherry could hear Egan on top of Numbnuts whispering shutup and cursing.

“Me en Cherry’ll go,” Egan whispered to Thomaston. Numbnuts disappeared in the darkness.

Cherry crawled behind Egan, crawled, duck-walked, slithered, down a narrow path and then into a thicket. They moved very little yet managed to open a tiny two-man cave in the growth. Then Egan left. He set out two claymore mines beside the path then returned to the cave. They positioned the radio between them, their rifles across their legs, frags spread before them, they sat for a long time without speaking. Both were awake, alert, listening.

Egan broke the silence after two hours. “How’s your lady?” he asked very quietly.

Cherry paused before answering, taking time to listen to the darkness. “Okay,” he answered. Then, “She’s a spoiled bitch.”

They spoke now very quietly, leaving long gaps between phrases to listen. “Good lookin?” Egan asked.

“Beautiful,” Cherry whispered.

“I’m a fucken fool when it comes to beautiful women,” Egan confessed.

“I’ve done some pretty dumb things myself,” Cherry admitted.

They sat silent again for a long time then Egan told Cherry an anecdote from his high school days. Because of the pauses the story took an hour. “I had a crush on this one lady,” Egan said. “She was captain of the cheerleaders and, Man, she had the greatest legs in the world … and I was a shy mothafucker … One time I take one of the other cheerleaders to a dance and we go parking afterward and I play all sorts of games so I can grab her tits and stick my hand on her pussy … feel her all over … had a great time. Word gets out I’m fast … shy me, fast. I aint never been a fast dude in my life but I don’t give a shit about this one so I grab her all over. Annie with the great legs lets it be known that she wants to go out with me and the next dance is after our last football game … I work up the nerve to ask her. I could talk to her but I couldn’t ask her out … finally I ask her … she’s let everyone know she wants to go with me so of course she accepts. I’m trippin. I don’t know if this is gettin across to ya. I had a crush on her … she was the prettiest girl in my school and I was a funny lookin Irish kid who tripped over his tongue. Annie says she’d go. I almost cream my fatigues on the spot.” Egan paused for a long time. He was not sure if Cherry was listening or if he could even hear him. He was not really sure he was speaking at all. “I take her to the dance and she’s got to sit up on some podium because she’s Queen of the Victory Parade … somethin like that. I’m gettin frustrated … can’t say anything cause I’m shy. After the dance we go out … we’re doublin with this dude who’s our star tailback. We go out to the bluffs … that’s where we always go parkin. He and his honey are gettin it on in the front seat while this lady and I, I’m terrified, we’re talkin in the back seat and I don’t know what to do. Then Annie leans over and begins kissin me and Man, I’m in number-ten shock. Like I can’t respond … Fucked up, huh?”

Cherry laughed very quietly, so quietly Egan did not hear. He said nothing for perhaps twenty minutes. Then he said, “I did that once too.” Long pause. “Once I had a crush on this chick. I useta walk by her house late at night … shit like that.”

“I useta do that with Annie,” Egan whispered.

Ten-minute pause. “One time I’m out cleanin the yard,” Cherry said. “She walked by … she said hi and I turned red. She walked on. Man, I waited til she was outa sight then I ran behind the stores, circled back up the block and came walkin down the sidewalk toward her … like three blocks away. All I could do was smile … she laughs and we walk by each other … Then I circle the buildings again. I think I gotta say somethin to her. I run up the backstreet to her street … sit against a tree and wait for her and she comes walkin up and she looks scared and runs by. I never talked to her once and I was always ashamed when I saw her after that.”

“Fucked up, huh?” Egan laughed.

“Yeah,” Cherry said.

Doc and Minh had gone to sleep on a tiny mound on the valley floor. It was not much of a mound but it had felt drier and softer than the surrounding mud and they had covered it with one poncho, covered themselves with the other and had gone to sleep. Suddenly they both woke and both were burning all over. They felt as if someone were lighting matches on their skin. Doc jumped and jerked. Minh rubbed himself all over. They both jumped up. They were on top an anthill and both of them were covered with ants. The ants bit their legs and backs and stomachs and scalps. The bites burned. There were ants in their boots. It was almost as if the ants had covered them cautiously then on command all began biting at once. It was pitch black. Doc and Minh tried to be silent but the ants were eating them. They pulled their gear away from the mound and stumbled on bushes in the dark. “Au, au,” Minh squealed quietly. “Mothafucka,” Doc cried grabbing his armpits and falling to his knees. They shook out their ponchos. Cahalan and Brooks rose and questioned them and helped them but they couldn’t get away from the ants. Doc sprayed a full bottle of insect repellent on himself. He covered his face. There were ants hiding in the kinks of his hair. He ripped at his scalp. He rubbed repellent into his hair and got it in his eyes and it stung. Minh splashed the repellent on his clothes but that did no good. They could not see the ants to brush them off. They stripped and washed themselves in repellent.

Sporadically through the night a single ant would sting one or the other.

The talk of their ladies had set Egan consciously to thinking of Stephanie. He would write her one more time, he decided. One short letter. He would write her in the morning, he decided, but he would think now about what he would say. Relaxing now, he penned in his mind. Can’t get enthusiastic about this war or this country anymore, he imagined writing. It isn’t a good war to stay at or to watch for very long. I’ve been here too long. Shit. I can’t write her that. He closed his eyes and tried to make her appear. He could feel her burning within him. Deep inside all good things burn, he told himself. All things of enough good for one to recognize their existence. Any feeling, if it is strong enough, if it works its way from the mind down to the viscera, is good. That’s where you are, Steph. You are strong enough in me to exist, to move me, to obsess me. Saying those words, saying her name, made him feel very clear-headed and peaceful.

Egan looked about in the silent blackness. He leaned against the radio and felt Cherry’s arm on the box. “I’m sackin,” he whispered.

“Roger that,” Cherry answered.

Now Egan dreamed of Stephanie. He could see her. They were in the park. When? It must have been very late. Pigeons cooed. Small birds tweeted. He laughed and danced and laughed again. The boughs of the trees swooshed with the wind in rhythm to his jig. Leaves swirled on the walks in miniature tornadoes. The sun felt warm. She sat there cold. She laughed at his jig. “Come on now,” he sang out. “Aren’t you alive? Can’t you feel the joy of this beautiful planet?” Stephanie sat and smiled and looked pretty. Perhaps she was angry. He had not interpreted it that way then. It’s nice to be free with the breeze, he had thought. To be high with the wind is wonderful but for her it is impossible. What’s the matter with her? What’s going on? Her blood seems to run too thickly through her brain for her to move. Perhaps it is her precision, her preciseness, that won’t allow her to move, to dance, to sing. That’s crazy, he now thought. She had such beauty of movement.

“Come here,” his image ordered her. She did not move. “Come here,” he pleaded. “Come and love with me.”

“You’re a fool,” Stephanie said graciously. Daniel heard her say it, heard her now. It had been a bitter thing to say and she looked away sorry for having said it but he had not been aware of her then, except that she seemed unable to move.

Perhaps he had known it. They both knew he had been too lax this time. He hadn’t written. He hadn’t called. How much time had he allowed to pass, he could not recall. It must have been too much. He had not even answered her letters. I got bogged down in my studies, he told himself. His memory of those last letters was hazy yet he could see excerpts of Stephanie’s beautiful handwriting.

I feel like you’re right here with me. Oh Daniel, I wish you were here. I really want to kiss you. When are you coming. I’m so anxious. I so want to see you and hear you.

One letter was a series of overlapping and interlocking sketches. They were exquisite. Faces of children, still lifes of pillows and wine bottles and candles in long slender candelabrums. And eyes. Very fine lines catching every detail of soft and harsh eyes.

The short letter arrived. This one burned deeply when the words passed through Egan’s mind.

Dear Daniel,

I don’t know what your opinion will be but I feel I must tell you what’s been happening to me these past months. Up until today I thought I was very much pregnant. I have been terribly upset—Oh Christ! I don’t even want to talk about it, but everything from suicide to running away has been clogging my head. Trying to make plans to go back to school but not knowing if I could see them through. I suppose you can imagine. I went to a doctor a few weeks ago and he said it was too early to tell. The relief of mind I had today was amazing.

I am going to school. Looked all day for a room but didn’t find one. It’s 1:30. I should be asleep but I had to write you. I tried writing before but I just couldn’t. You know, Daniel, I think you’re more trouble than you’re worth. I’ve been very much alone. It was bad throwing around the thought of pregnancy again.

Daniel, when trust goes out of love, then love has lost its meaning and is no more. Trust is part of love and freedom and friendship. As trust runs down relationships strain and the habitants become jailed by their fears of each other. Trust is not built on words or pleasantries. It has to be a mutual pact built on sharing and on responsibility. One must give as one receives. One must respect the life of another, and must have that respect returned for trust and love to grow and for one to say and have said of him, “Him I trust. Him I love.”

I’m sorry about this letter but it’s late—I’m tired—but I knew I couldn’t sleep until I wrote.

Sometimes I wonder where my mind, my heart and my soul are. Or if they even are. I’m sure they are but blissfulness makes them love to hide.

Love,

Stephanie

I was crazy about you, Daniel said to her in his mind as he lay in the muck of the valley floor. Don’t you see, he tried to explain. I had to go. We were caught up by a world that ran us. That ran over us. I remember saying good-bye to you. You always made me so happy. I think I said to you, ‘Neither you nor I wish to have the things having each other would bring. You’d never have security with me and I’d never feel free with you.’ Oh Steph, I remember saying that. I remember the song that was playing in the car the day I left. We’ll Sing In The Sunshine. To me, it was our song. Stephanie, now my year is over. Oh shit. I’m sorry. I remember you said I hurt you. I wanted to bring you sunshine. Wanted to laugh every day. I hurt you. I don’t think it ever sunk in until maybe just now. Oh God, I’m such a dumb Mick. How long is that? Three years? I’m pretty slow. You’ll have to help me. Can I say it now—I’m sorry if I hurt you.

SIGNIFICANT ACTIVITIES

THE FOLLOWING RESULTS FOR OPERATIONS IN THE O’REILLY/ BARNETT/JEROME AREA WERE REPORTED FOR THE 24-HOUR PERIOD ENDING 2359 20 AUGUST 70:

DURING THE ENTIRE DAY SPORADIC FIGHTING WAS REPORTED BY THE 2D AND 4TH BNS, 1ST REGT (ARVN) IN THE FIREBASE O’REILLY AREA. ENEMY LOSSES INCLUDED 250 ONE-HALF POUND SACHEL CHARGES, 100 82MM MORTAR ROUNDS AND FIVE CREW SERVED WEAPONS. ARVN CASUALTIES WERE TWO KIA AND NINE WIA.,

THE 7TH BN, 402D INF CONTINUED OPERATIONS IN THE VICINITY OF FIREBASE BARNETT ON THIS DATE WITH ONLY LIGHT CONTACT. AT 1427 HOURS THE BATTALION COMMANDER’S C & C HELICOPTER SPOTTED FOUR NVA IN THE OPEN. ARTILLERY WAS EMPLOYED RESULTING IN TWO NVA KIA. AT 1710 HOURS A HELICOPTER FROM D COMPANY, 101ST AVIATION BN RECEIVED .51 CALIBER MACHINE GUN FIRE WHILE DEPARTING FROM FIREBASE BARNETT. ONE US SOLDIER WAS WOUNDED. THE AIRCRAFT RECEIVED MINOR DAMAGE.

AT 1830 HOURS FIREBASE BARNETT RECEIVED 19 ROUNDS OF 61MM MORTAR FIRE, SEVEN IMPACTING WITHIN THE PERIMETER. ONE US SOLDIER WAS WOUNDED. COUNTER BATTERY FIRE WAS EMPLOYED WITH UNKNOWN RESULTS.