CHAPTER 28

21-23 AUGUST 1970 CAMPOBASSO

The sky yellowed and stood still. Alpha froze. No one seemed to breathe. Then the mist began to move, to roll, to twist. Lightning split the heavens, flashbulbed the mist. Thunder burst like great artillery. Rain fell heavy, hard, in close thick drops. Alpha moved.

Egan led off. Cherry walked his slack. 1st Plt followed, then the Co CP, 2d Plt in the protected middle and 3d at rear security. The column moved quickly beneath the dawn storm, moved northwest then north to the river’s edge. The move began three days and nights which lost Alpha in a blurring haze of time and space and rain. The recent past dissolved. The near future never approached. Black nights passed to dark gray days almost without distinction. Alpha scrapped with the NVA—small running firefights, ambushes, pursuits. The actions mingled with non-action, became encased in hardened empty dullness, in glass-eyed madness.

“Fuck it,” they repeated a thousand times. “Fuck it. Don’t mean nothin. Drive on.” The mantra of the infantry.

“Got it,” Cherry said. He had stripped in the cold rain, tied the rope about his waist and had slipped into the river. They were 800 meters west of the knoll at valley center. The frigid water chilled him and softened his oozing sores. He was barely cognizant of the chill and the sores. He focused his eyes and mind on the north shore. Artillery rounds exploded 200 to 500 meters downriver. Mortar rounds impacted randomly upriver.

“Go for it,” Egan whispered. Cherry dove.

1st Plt was spread on line at the river’s edge, a meter inside the vegetation. All eyes were on Cherry breast stroking silently against the rainswell waters, or on the north bank shrub mist searching for movement. Asses were in three inches of cold rain mud.

“This is fucked,” Jax whispered to Doc. “This mofuck division fucked up.”

“What he pushin fo?” Doc shook his head woefully. “What fo, Mista?”

“L-T gettin fucked up,” Jax said.

“He pushin too hard,” Doc said. “He becomin a lifer. I can’t believe it, Bro. He aint nevah goan leave.”

“We’s all gowin die here,” Jax said painfully. “We’s all gowin die.”

“Why, Mista? Why?”

“Asshole.” Egan joined Doc and Jax in the grass. He raged quietly not perceiving their mood.

“What’s happenin, Bro?” Doc asked.

“Rope’s goina drown Little Brother in the blue feature. Assholes. Shoulda never sent him across. Nobody could swim that shit.” Cherry was approaching mid-stream, pulling, snapping into a short glide, pulling, working like mad, making no discernible progress through the main current.

“Dis fucked,” Jax repeated.

“Fuck it,” Egan snarled.

Cherry exerted, inched toward the north bank. The current was forcing him downstream, the rope holding him in the on-rush. He reached, pulled, extended, pulled. All of 1st Plt watched. Pull, they cheered him silently. Pull. Cherry’s frogkick clapped, his arms pulled, he shot forward a foot, glided, the current pushed him back ten inches, he stroked again. Past mid-stream, toward the north bank, the current fell off. He reached, pulled, reached the bank. Up. Out. Disappeared into the land of Leech Row. Egan stripped off everything except his fatigue pants. He plunged into the river with his and Cherry’s M-16s and pulled himself across on the rope. Mechanically 1st Plt converged on the rope, waded into the river and pulled. Cherry returned to the water as lifeguard and guide, then Egan assisted and then Brooks.

“I didn’t know black men could swim,” Egan nudged Cherry over Brooks’ back, all three fighting cold riverwater swell to stay in place.

“They can’t,” Brooks laughed looking quickly from Egan to Cherry. “I’ve got Dago blood in me. The oil keeps me up.”

Then they were up and out and Alpha was again moving quickly, moving, spraying insect repellent on the leeches, rain diluting the repellent, leeches sucking, boonierats bitching. “Fuck it. Don’t mean nothin. Drive on.”

Alpha followed a streambed north. It was hardly more than a watery shallow gutter in the valley floor yet it afforded two advantages. It was lower than the surrounding earth giving them a natural protective, concealing trench. And it made the going easier. Woody brush and vegetation choked both streambanks. Branches bridged the narrow trench at three, four, five feet. Only grass grew in the streambed, grass and leeches. Thighs and legs swished through the grass re-saturating fatigues and boots with every step. Moneski led Alpha north 150 meters through the tunnel then emerged east into a thicket. Alpha inched across the valley floor crossing trail after trail, red balls, and an engineered road with traffic signs that Minh said warned enemy logistic and supply troops against loitering. Alpha moved east 700 meters to another dense thicket, a thicket across the river from the knoll, 150 meters north of the swollen river.

“Man, this is so thick, we could stay right here,” Egan told Brooks. “Nobody could touch us. They couldn’t attack into this shit. With a halfdozen OPs en LPs, we could wreak havoc down here.”

“No way, Man,” Bill Brown shook his head.

Brooks smiled. Egan asked Brown, “Why not? Think about it. If they were set up in a thicket as thick as this shit, could we attack them? Ya can’t walk in here. Ya can’t move up on anybody in force.”

“Like Br’er Rabbit,” Doc chuckled nastily from behind. “Doan throw me in the briar patch. L-T, doan throw me up in them hills.”

“It may be possible,” Brooks said. He had already decided. He called a halt.

Alpha was in the middle of an elongated network of NVA supply trails. Brooks ordered them to circle up, slip in and hide: Let the morning and the rain come.

Alpha hid. Morning came. The rain continued. The position was a low area, a large shallow pit, surrounded by a natural earthen berm and cloaked beneath a variety of very dense vegetation. The CP set up near the center of the pit and the platoons manned the berm. Brooks had the word passed, “We’re staying until tomorrow.” The boonierats dug in quietly. They carved small hollows and trenches under the thickest brambles or bamboo clusters. Quarters were close. Two of every three men slept, slept soggy, rested, prepared for the day and night to come.

Like all Americans they could not resist giving their location a name. Their base NDP came to be known amongst them as Campobasso. It was Cherry who came up with the name. In Italian Campobasso meant low field or possibly base camp. Cherry did not tell the L-T or Egan or any of his boonierat brothers that Campobasso was his maternal grandparents’ hometown. He simply suggested the name and it stuck. The name fit. It was easy radio-ese. Alpha used it. Cherry loved it.

“What do you think, Pop?” Brooks whispered to Pop Randalph.

“Don’t know, Sir,” Pop answered in his high hoarse whisper.

Brooks sat cross-legged, draped with a poncho, his notebook and his maps across his lap. “Three tours? Why Pop? What makes you keep coming back for more?” The L-T’s voice was barely audible.

“You know why I’m heah, Sir?” Pop rasped. “I’m heah, Sir, because I am a soldier. An I’m a good soldier. I’m a better platoon sergeant than you’ll find anywhere. Except for that dumb son of a bitch, Mohnsen, I’d have a near perfect record.”

“But what keeps you here?” Brooks asked. “What keeps you as a soldier here?”

“Sir,” Pop’s face twitched. “We have a mission. An I can accomplish that mission better’n anyone else. Better en with less loss of life.”

“Do you really believe that, Pop?” Brooks asked. He asked it sincerely without the slightest skepticism.

“Yes Sir,” Pop answered.

“Good,” Brooks said. “Who’s going with you?”

“Sergeant Egan en his cherry.”

“Good,” Brooks said.

Pop, Egan and Cherry had volunteered for the first MA mission. From Campobasso Brooks had already sent out six LP/ OPs. Recon patrols were being organized. Ambush teams would come later. Brooks called them all Rover Teams and the name excited the boonierats. At dusk they would go out in every direction to determine the enemy situation and feed information to the commander for the planned assault on the headquarters complex, if they could find it, if it existed. But first, Brooks decided, we must disrupt NVA movement all about us. We’ll set MAs on the red balls.

The three men of the first team emptied their pockets. They removed all excess equipment. Using only light webbing Cherry strapped his radio tightly against his back. Egan carried five claymore mines in a towel. Pop carried a used radio battery, rolls of det cord and trip wire, a slide-type trigger mechanism and blasting caps. All three carried their 16s, bandoleers of magazines and four fragmentation grenades each.

“Break squelch twice,” El Paso instructed Cherry. “Then all’s cool. Three times you sittin tight waitin for trouble to pass. Four, you comin back in. We’ll notify the perimeter.”

“Right on, Bro,” Cherry whispered.

Rover Team Stephanie departed north, moving quickly beyond the perimeter, out beyond the LP/ OP toward the enemy road below the north escarpment. Wind and rain covered their movement and the sound of their footfalls. Pop led them unmercifully under the heaviest thickets, through the most vile muck, into the stench of sewer-decay humus, a path the NVA would never choose, would never expect Americans to attempt. Much of the time they crawled. Between each motion they lay flat, listening. They moved more and more slowly, crossing trails only when necessary, skirting them when possible. They lay motionless, face-in-the-muck prone for ever-increasing periods. Then they crawled again. The road/ red ball was north, they had only to avoid enemy and head generally north and they would hit it. “If they can’t see you, they can’t shoot you,” Egan had said to Cherry before they had left. “They aint goan see us,” Pop winked.

Now they lay before the road, in a foul quagmire. They lay prone beneath brambles. They observed. They listened. Their ears were stimulated just below their threshold of recognition. Had an enemy squad just passed? Had they almost been stepped on? It reminded Cherry of summer night hide-and-seek when he was young. His favorite place to hide had been in the thick grass below the quince trees. There he would watch his brother Vic walk by, almost step on him. Cherry laughed silently to himself. Can’t find me, mothafuckas. His body trembled.

Egan looked at Cherry. That dumb mothafucker, he thought. He’s got to experience it all. Can’t tell him a fuckin thing. Egan wanted to shake him. Cherry, he wanted to say, for godchristsakes can’t you listen and learn? Can’t you see all I’m tryin ta do is teach you, speed up your learning so you don’t have to make the same mistakes I made? It’s a wonder mankind’s gotten as far as it has, Egan thought. It’s a wonder we’re not all still learning and relearning that fire burns. Fuck it. Maybe we are.

L-T’s goan nuts, Pop thought, though he could not describe it to himself. Tactically their maneuver was perfect. He had never seen such an AO and he had never known a commander to direct and execute an infiltration so superbly. Yet something was not right. L-T en his questions, Pop scrunched up his face thinking. L-T goan nuts.

Cherry’s thoughts skipped. We could talk about our home lives and our upbringing. I could tell Jax or Doc about my family and they could tell me about theirs. I’d say, ‘I never had a black friend. I mean, like, I never truly knew a black person.’ I could say, ‘I grew up with blacks. You know, we went to school together, played together. Every once in a while we went to each other’s homes. But it was always like another world to me, as if I didn’t understand the language or wasn’t allowed. It was as if there was a law against getting to know a black.’ And then his imagination filled with Doc saying, ‘Fo blacks, it is a law.’ Squelch broke twice on Cherry’s radio, El Paso signaling for a situation report. Cherry keyed his handset twice and stared at the road. All was still except the rain and the wind.

Pop stealthily slipped from the muck and slid to the road. Egan signaled Cherry to stay put. He followed Pop onto the road. Without an utterance they commenced to deploy the ambush. Egan set one claymore two feet off the road, below brush, ten feet up the road. He angled the mine slightly upward, up and across the road. Pop unscrewed the plastic fastener used to secure a blasting cap, inserted an end of det cord and screwed the fastener back in place. Then he unrolled the cord and brought it across the road to where Egan was aiming a second claymore. Pop measured the cord, cut it and returned to the road. Carefully he camouflaged the cord, burying it in the road mud, being extra careful to reconstruct the cartwheel grooves after burying the cord. Egan waited until Pop was finished. The two worked methodically, steadily. Egan inserted and secured the cord to one side of the second claymore connecting the first two mines. Pop took over and secured the new end of the det cord roll to the second insert on the mine and unrolled and weaved the cord through the brush down the trail to where Egan was aiming a third claymore directly across toward Cherry. Pop connected this mine to the second. Egan set up a fourth and fifth down the road, one on each side. Pop daisy-chained the remaining mines to the first three. At the center of the MA, opposite Cherry, Egan stretched a monofilament trip wire line across, three inches above, the road. He fastened the trip wire to one side of a slide trigger. Egan secured the other side of the trigger to a rigid brush stump and camouflaged it. From one side of the trigger he ran a blasting cap wire to one terminal of the battery. Pop removed an electrical blasting cap from his shirt pocket, unwound the wires, attached one to the trigger slide and inserted the cap into the first claymore. Egan checked the slide mechanism, checked the trip wire and camouflage for the mines and the battery. Then he retreated to Cherry. Cherry watched fascinated, a smile on his face, twinkles in his eyes. Pop signaled for them both to withdraw. He quickly visually rechecked the booby trap then armed it by attaching the second blasting cap wire to the second terminal of the battery.

While Pop, Egan and Cherry were north on the road, Rover Team Claudia—Snell, Nahele and McQueen of 3d Plt—worked their way south to the river then upstream 200 meters. They sat immobile observing the river and across to the knoll. Within twenty minutes of set-up they spotted an NVA squad on the south riverbank. The enemy squad began unloading materials from a long wooden sampan. Snell radioed El Paso, spoke with Brooks, then called Armageddon Two. “Fire mission. Over.”

Rounds landed in the river and on the swamp valley floor geysering riverwater and valley mud up with the flash and cordite smoke. The next three salvos were airbursts and geysered down showers of explosion-propelled shrapnel. The arty raid killed, all members of Rover Team Claudia agreed, at least five NVA. They were credited with a body count of four.

“¿Que pasa?” Brooks asked El Paso. “You are, L-T,” El Paso smiled.

“What are you thinking?” Brooks asked staring intensely at his senior RTO.

“I was thinking of my mother,” El Paso answered. “You know, L-T, she used to say to me, ‘Rafael, come in and stay with your mother. Today, I am very tired.’ She used to say that to me all of the time.” Brooks rubbed his hand up under his baseball cap, wiped rain from his forehead, and continued searching El Paso’s face. “I should have taken her advice,” El Paso said.

Brooks smiled. He and El Paso were the very center of Alpha and he liked that. He liked his RTO. Here they sat together on one poncho, under one poncho, wet together, in control together. They had spoken very little for days. Most of their interaction had been official. Earlier this day they had briefly discussed left-right politics but each time they began they had been interrupted by demands of the mission. Brooks opened his notebook carefully under the poncho.

“What were you telling me about Spanish?” Brooks asked after a pause.

“You mean the con?” El Paso asked.

“Yes,” Brooks said eagerly.

“It is like this,” El Paso began in a voice easy to listen to, as if he were telling a story. “You see, a Chicano is with something. Anglos, they are for something. We do not say I am for this or for that, we say con, with this or with that. When you say you are for something you disassociate yourself from it. You and it are different. Don’t you agree? But Spanish-speaking people, we are with an idea or an issue. We say I am with this candidate or with this policy. It is we and we are it. It does not exist by itself as it does for the Anglos. When my people talk about the government it is not to be an entity by itself that we must serve. It is us and it must serve us.”

Brooks made a few notes then said, “I hear you yet I don’t see that in reality.”

“Maybe you do not know enough about Spanish-speaking people. It is the con, why we are so passionate.”

“The con,” Brooks repeated to himself attempting to assimilate the concept. He repeated it again.

“Before we were talking about right and left governments,” El Paso said, “and right or left factions. I don’t think that is a realistic representation of American politics. L-T, you are interested in words as symbols and how they affect our thoughts. If we continually use right-left dichotomies to describe a particular polarization, does the description become part of the cause for the polarization?”

“I don’t know,” Brooks said writing the question down.

“This is what I think. Politics are not lineal. The left-center-right line is a poor descriptive symbol. Let’s put a policy decision, a topic like this war, in the center. The right demands that we remain here, that we redouble our effort. And the right criticizes the government for not following a rightist course. From the left there are others pulling at the government. They want all American troops withdrawn now. They criticize the government not following a leftist course. And we only have two alternatives. Maybe that is because that is the rules we set up for ourselves. But it is not the real situation.

“What we, the government and the people of the United States, do could be better represented by a sphere with a dot at the center. The dot is our policy. On the surface of the sphere are all the interested parties. There’s Dow Chemical with a big line to the dot and there’s Irma Dinkydau from Lost City, Nevada, with a thread, and there are a hundred million others. Everybody’s pulling the dot in different directions and it’s staying pretty close to center.”

“Hey,” Brooks smiled. “And true polarization occurs only when the surface participants are pushed to the poles. Perhaps when you have heavy concentrations of interest groups. Or maybe one side polarizing forces the other side to polarize.”

“Yes,” El Paso agreed. “But in a free society you do not get complete polarization because the interest groups are capable of wandering around anywhere on the surface of the sphere.”

“If they know it a sphere,” Doc said sliding under their poncho. He had overheard fragments of their conversation from his wet hole only an arm’s reach away. “What happen, Mista, when somebody come long an purge an entire pole? Huh? Then your dot gonna be way outa whack.”

Egan and Cherry materialized silently from the mistblur. “Rover Team Stephanie reports,” Cherry whispered.

“Yeah,” El Paso said attempting to disarm Doc’s argument, ignoring the return of the rover team. El Paso liked his model and he wanted to defend it. “However, we don’t have purges in our society. Not great purges like they’ve had in Russia or China. See, there people are forced off the sphere. There people can’t stabilize the policy dots in the center because they aint allowed to wander about and pressure and pull the dot from all angles.”

“What you mean we don’t got great purges? What happened to the red race, Mista? You fogettin somethin. White fuckas always have purges.”

“Hey,” Egan jumped right in, “we got repression of minorities and we got some purged people but it’s not like in the Soviet Union or in China or even in North Vietnam. Asian fuckas,” Egan mocked Doc’s voice, “always have purges. You can’t name a great American purge.”

“We couldn’t have one now,” Cherry said. “Too many people would stand up and object.”

“Exactly,” El Paso stated firmly. “Free criticism is good. It keeps government honest and stable.”

The conversation turned away from racial problems and back to war. El Paso delivered a lecture on the legality of the war. “There are very sound arguments holding this war to be unconstitutional,” El Paso said. “Like when Nixon decided to send troops into Cambodia. That was not legal. He reigns over our lives, he reigns over the country. He makes decisions by himself without regard to anyone else pulling on the policy dot, almost as if he were a dictator. It simply cannot be legal. Not under these circumstances. The president can order invasions if our country is threatened. The Constitution says that that is okay. And there are legal precedents for similar action. FDR sent Americans into North Africa and then into Europe without congressional approval but the power to declare war does not rest with the president. That power is in the hands of Congress. Congress must declare war and the president must approve.

“There are many precedents in our history which extend the president’s original war powers. President Polk attacked Mexico in 1845 without congressional approval. Only after the fact did Congress declare war. President Wilson, he had the navy bombard Vera Cruz and he sent American troops into Mexico after Pancho Villa. But no earlier president ever stretched his powers like Johnson in 1965. He completely usurped all the war-declaring power from Congress.”

“Hey, what about the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution?” Brooks asked.

“That only authorized the president to retaliate to that one attack. It can’t be used to justify half a million men and full-scale war. Besides, under the Constitution, Congress cannot give its powers away.”

“What about the SEATO treaty?” Cherry asked.

“That treaty states that all countries involved must act in accordance with their constitutional processes. A treaty cannot supercede the constitution.”

“Then why are you here?” Brooks asked.

“L-T, if I did not come, I’d be in jail,” El Paso said.

During the discussion Brooks had been watching first El Paso, then Egan, then Cherry, then Doc. His mind jumped back to earlier statements. “Do we each have within us,” Brooks asked, “a dot which we pull in many directions, a dot which determines our personal policy and course?”

There was contact to the south. A single burst of fire, a silent second, then answering fire and mingling fire. Then all was quiet. At Campobasso Brooks and El Paso waited for the report while the others prepared themselves. The report seemed a long time coming. Then Rover Team Danielle, four boonierats from 1st Plt, 2d Sqd led by Moneski, radioed its report. They had made Alpha’s first direct contact since the river crossing. It had been short, small, sweet. Danielle ambushed a two-man NVA trail watcher unit. The Americans had set up moments before in an NVA position off one trail. The NVA had come from behind, unsuspecting, ready to move into their own position. One enemy soldier had been killed instantly. The other was hit and had fled. Rover Team Danielle pursued, caught the wounded man, took and returned fire, blowing the NVA soldier to pieces. The team sustained no casualties.

The nightly CP meeting on the 21st took place before dusk. Rain had fallen all day, the monotonous pattering drops being sporadically disrupted by cloudbursts. The sky had again settled back, it seemed in response to Brooks’ meeting, to the dark gray of steady rain. The meeting was brief. Eighteen platoon members attended, all the platoon sergeants and leaders and the platoon CP RTOs and all of the squad leaders or a stand-in for those on patrol. The soldiers sat close together, almost in each other’s laps, to hear Brooks give the operational orders for the next two days.

The NVA were not accustomed to American units working at night, moving at night and setting up during the day. They were not accustomed to it because so few American units did it. Brooks had been consulting his advisers individually since resupply and he was now convinced Alpha was in position and could pull it off. “We’re going to pick them apart from right here,” Brooks said. “Hide and hit. Melt into the mud and ambush them. If this is as important a supply area as S-2 says it is, they’ve got to be moving. It’ll be no different than our usual nightly ambushes except that we’re going to have twelve ambush teams out at once. This time, you’re not ambush teams. You’ll be Rover Teams. And you’ll be out for two days.” Brooks detailed the operation. Half of every squad would go; half would stay in or near Campobasso. The company and platoon CPs would provide men for three teams and radios for four. Brooks assigned each Rover Team a specific Area of Operation. He suggested ambush locations in each area. He rose and climbed among his men, pointing out to each leader, on the individual’s map, the spots he thought looked promising, the trails in each area he had marked on his map from the first circuit they had made about the knoll. “Hide and hit,” Brooks said coldly. “Hit and run. Evade detection. Don’t engage more than you can kill immediately. Ambush.”

“Ambush,” Moneski repeated. “Just like earlier today. It’s a dream.”

“Snipe,” Brooks said. “We’ve got three Starlight scopes. Use them.”

“Snipe,” Snell nodded. “And call in arty.”

“Let arty get some.” Brooks smiled. The group was psyching up. Cold blood lust, contempt for the enemy, spewed from one then another. “Use your MAs,” Brooks said.

“Blow em away,” Catt cooed.

“Kill the fuckers,” Cherry giggled venomously.

“Kill the fuckers,” Mohnsen cried, wept bitter tears.

Brooks let them seethe then purposefully settled them back down with a few cautions and a few questions. “Field ingenuity,” he whispered. “Every boonierat must think for himself, adjust himself to the situation he finds himself in. You guys have to be more versatile, more flexible than the dinks. And you have to be smarter. Think about what you are going to do before you do it. Plan. Out-fox them. Don’t go out of your own AOs without clearance. Don’t ambush each other. No chatter on the nets. Rovers!”

“Aye, L-T,” they whispered.

“Kill em, kill em, kill em,” Mohnsen beat his rifle butt against the ground.

“Teams Cindy, Joan, Ellen and Laurie,” Brooks whispered, “you leave at 1900 hours. Teams Claudia, Beth, Irene and Mary, you leave at 1915 hours. Teams Danielle, Suzie, Jill and Stephanie—1930.”

Before the first boonierat could rise an ear-splitting concussion rocked Alpha. The MA on the road below the north escarpment had detonated.

As Rover Team Stephanie—now Egan, Cherry and Bo Denhardt—rucked up, Brooks collared Egan. “I want to ask you some questions before you sky, Danny,” Brooks said. He was a man now completely different from the one who had led the briefing, rally, only minutes before. He spoke in his graduate student voice, concerned, contemplative, the exact opposite of the previous passion. And he seemed unaware of the change. Indeed Egan noted what seemed to him to be a complete repression or denial of the commander role. It made Egan uncomfortable.

“Danny,” Brooks said meekly, “what causes conflict?”

Egan dropped his ruck and sat atop it. “I’ll tell ya what I know,” he said. “I been thinkin about this for ya. You’ll have ta check it out for yourself but here’s some shit I remember from school. And some shit I just think.”

Brooks smiled softly in the rain, silently begging Egan’s indulgence as he uncovered his notebook and covered it and himself with his poncho.

“I had an engineering prof, guy named Tom Wheeler, who did his thesis on the effects of technological advances on population demographics. Something like that. Basically what he said was every major advance in technology is followed by a period of prosperity, then a population explosion. Works like this. A technological advance alleviates the pressure of population but then the pressure builds up again except now to a higher level. Follow me?”

“Kinda,” Brooks whispered, writing.

“Look,” Egan said. “Go way back. Hunter/ gatherer mankind learns how to herd animals. He stabilizes his life following pastures. For a while everyone has food and prospers. Then there’s a population explosion followed by overcrowding, disease and famine.”

“And war?”

“Yeah, I guess. Anyway, now nomadic mankind learns how to cultivate crops. He settles down on fertile lands and he becomes more stabilized but at a more complex level. For a while everyone prospers, has food, the whole thing. Then there’s a population explosion followed by overcrowding, disease, famine and probably war and migration. Mankind then learns how to store food against famine, how to irrigate against drought. For a while everyone prospers, again at a more complex level. With no pressure man seems to be more fertile. The population explodes and puts the pressure back on and the same problems occur.”

“Are you saying,” Brooks asked softly, “that war is a means of limiting population?”

“Wait a minute,” Egan said. “I don’t know if I got there yet.”

“Excuse me,” Brooks apologized.

Egan’s concentration on his thoughts deepened. “Each advance brings greater stability yet with a higher, more complex structure supporting it. Each period of stability brings a population explosion. That can be documented. If you plot the growth of human population before every major increase you’ll find a major technological advance. After each major increase you find population pressure and war. Pressure is conflict, L-T. Want to stop the pressure? After the next advance, stop people from fuckin each other.”

“Sew up all the cunts of the Third World, huh?” Brooks joked, laughed, trying to lessen Egan’s intensity, and also trying to reduce Egan’s last statement to the absurd because to Brooks it smacked of racism.

“The whole world,” Egan said sharply, defensively. “Fuck it, Man. You listenin? There aint no chance about this. There aint no such thing as chance. Only ignorance of natural laws.”

“I didn’t mean to put your theory down,” Brooks said. “I’ve been writing what you’ve been saying. How does it fit though, in a world where some nations are rich and some poor? Some advanced, some not?”

“Advances in technology don’t just happen, L-T,” Egan said calmer. “Technology grows. It has prerequisites.” Brooks shifted beneath his poncho. Egan slid lower on his ruck, then slid off the ruck and onto the ground next to the lieutenant. “Look, in what are today’s industrial nations, before they were industrial, certain conditions existed. The advanced societies today were the early machine societies. And those societies changed to accept new styles of living. And they gave up a lot to do it.”

“What did they …”

“Wait a minute. In places like England there was a belief in rational thought, in natural sciences and in mathematics. They prized analytical thinking. They had to give up more comfortable religions for ones that would accommodate their science. Maybe they gave up their souls. But see, L-T,” Egan was concentrating hard again, burning his words out quietly, “those things led to a high degree of technology built on a substructure of technology. The less complex fed the more complex. Technology, with only minor lapses, stayed ahead of their population pressures. If the pressure ever catches up and undermines the substructure all developed countries have a long way to fall.”

“Well, why can’t Vietnam use the technology too?” Brooks asked. “If they could use it to stay ahead of their population pressures there’d be no war.”

“No base. Development is not a matter of the industrialized nations giving equipment and advice to the Third World. That just doesn’t do it.” Egan was trying to pull old thoughts from areas of his mind that he had not used in a long time. “It just hasn’t worked that way,” Egan said. “These people can blame America or western Europe for conspiring to keep them down, for keeping the price of their raw materials low while selling high-priced finished goods to them but the fact is there’s no conspiracy. The conspiracy is in the minds of communists who want to control these people. It’s really a matter of no base structure.”

“Then what you’re saying,” Brooks whispered, “is that Third World societies just haven’t accepted the pain of giving up their old cultures and building the base for new westernized forms.”

“Well, yeah. There it is, L-T. These people got something we lost. To gain economic prosperity you got to want to work, you got to want that wealth bad enough to work at boring dehumanized work, highly technical work. You got to love machines like papa-san loves his water-bo. Cause that’s what technological advances are.”

“We think ourselves into what we are and our thought patterns are determined by the culture of our upbringing,” Brooks repeated a statement of his own theory which he wanted to tie to Egan’s.

“Oh. Okay,” Egan said. “Now I read you lumpy chicken. That’s what you meant when you said we think ourselves into war.”

“Yeah,” Brooks said. “That’s what I meant. So, industrialism is based on a people whose culture identifies with strong causative forces, with logical cause and effect patterns of thought. And western culture is based on logical thought patterns. And to get that we gave up something.”

“Yep,” Egan agreed. “Or at least we accepted something along with it that isn’t positive.”

“War,” Brooks said.

“It’s inevitable,” Egan said.

“We think ourselves into it and our minds don’t have an alternative. We’re a war-or-peace culture.” Brooks wrote that down.

The two of them sat silently in the rain, in the gray darkness, feeling close again. For some moments neither spoke. The valley seemed quiet. Artillery rounds were bursting far away. The noise of the rain had become so normal they did not notice it. Campobasso held only twenty-five soldiers and in the thicket none could be seen.

“Do you think war is against human nature?” Brooks asked just as Egan was about to rise to leave.

“No way,” Egan said settling back down. “People are always sayin it’s against human nature for man to war against man.” Egan spoke with contempt for the idea. “They say any advocate of war is against mankind. You can make just as good an argument for war being man’s nature. If you want the truth all you gotta say is man’s nature is intermittently warlike. War and peace. They have a continuous, maybe sine-like, maybe erratic, function. Did you know that on any given day there’s an average of twelve wars goin on on earth? There’s been over a hundred wars since World War Two. You don’t gotta justify war. Fuck the pansyass politicians and the pantywaist left. War’s its own justification.”

“That’s sad,” Brooks said.

“Why?” Egan demanded.

“We’re here and that justifies our being here?” Brooks made it sound ridiculous.

“The only justification you need for Nam is we’re doin it. It is, thus it is right. That goes for everything. If it is, so it is.”

“That’s crazy, Danny.”

“Don’t worry, L-T. It’s supposed to be. The stupider the war, the more the blunders, the better for mankind. Shit, if we ever become one hundred percent proficient at killing each other, then we’ll kill one hundred percent of us minus one. Like if we have thermo-nuclear war. We’re a lot better off runnin around with 16s than if we begin tossin ICBMs at each other.”

“Why can’t we change mankind and eliminate the need for conflict yet still remain different and flexible. It would only require tolerance.”

“Never happen.”

“Why?”

“You’d have ta change it all—every last man, woman and child—if you wanted ta break the cycle of peace-war-peace-war. You’d have ta build a new base. If you can’t change the system that produces war there’s one thing you best mothafuckin do—you better win them fuckin wars.”

“Amen,” Brooks said.

Egan began rising. “We gotta get to our AO,” he said to Brooks. “I gotta find what happened to the MA.”

“Wait a minute,” Brooks said. “I want to ask you just ah … about something else.”

“Yeah.”

“I want to switch to personal conflict. Like,” Brooks hesitated then nearly blurted it out loud instead of whispering it in his field voice, “like between my wife and me. You know the situation?”

“Yeah. I know.”

“You ever not been able to get it up?” Brooks asked.

“You mean like …”

“Yeah.”

“When drinkin,” Egan admitted.

“What about, you know, like when perfectly sober?” Brooks asked.

“I never had that problem,” Egan said, “but I think it’s common. Temporary impotence they call it. Like if you’re nervous. Playboy, I think, they had an article on it. I think it said it happens to fifty percent of all dudes at one time or another.”

“Really?” Brooks was amazed.

“Yeah.”

“Ah …” Brooks began slowly again, “have you ever fantasized about another man being with your lady?” He now had almost no voice at all. “I mean, like seeing an image of another dude and your lady making love?”

“Oh yeah,” Egan answered robustly. “All the time. I think everybody does that.” Suddenly to Egan, Brooks seemed transparent.

“It doesn’t mean, ah, like ah …”

“This is really botherin you, huh?”

“Yeah. I guess so.”

“Happen in Hawaii? Begin there?”

“Yeah. How’d you know?”

“Same thing happened to Hughes. Happened to Rattler too.”

“Really?” Again Brooks was amazed. “What about, like seeing you and another guy and your lady? Three of you?”

“Yeah. Sometimes,” Egan said. “I don’t think a guy can get it on with a lady who he knows has had other dudes and at some point not think when he’s eatin her he’s gettin some other dude’s cum or when she’s stickin her tongue in his mouth thinkin like she’d wrapped that same tongue around somebody else’s meat. It’s almost like he was blowin the other dude.”

Brooks looked at Egan, shocked. Then subdued he said, “Yeah. I guess so.”

“Yeah,” Egan continued. “Rattler said the Doc … not Doc but the shrink at Division … he called it the Nam Syndrome.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. Rattler thought he was turnin fag. He was really shook up, L-T. You didn’t know him then. He was really nuts. That’s why he went to the shrink.”

“I thought that was because of what happened on 714 and 882?”

“Well, he couldn’t come out en say somethin like that.”

“Yeah, I guess not,” Brooks agreed. “Hey, Danny, ah, either of those guys tell you what happened, ah, what kind of thoughts …”

“Yeah, that’s what I mean,” Egan said. “Rattler said he kept jerkin off fantasizin he was gettin butt-fucked.”

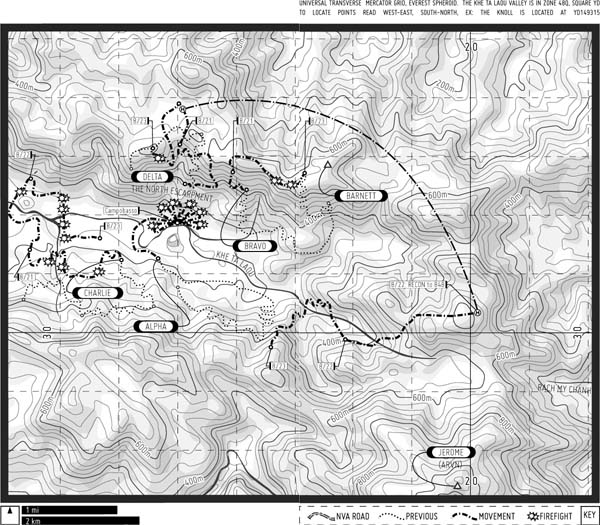

A single shot cracked the air. Nothing more. It came from south and west of the CP. In the rain splattered valley night the exact direction and distance of a single shot was impossible to determine. An aerial diagram of Alpha’s set up would have looked like the cross-section of an orange cut perpendicular to the axis. The very center would be almost empty. Only a skeleton CP remained. The first circle out would be formed by the apex of the sections. This would be the thinned though still tightly packed berm perimeter of Campobasso. Farther out, spaced almost evenly about the center, are six dots, seeds, LP/ OPs protecting the center. Expanding beyond and filling the circle are twelve sections, the AOs of the rover teams. To the south is the river. To the north is the road. The teams with sections to the southwest were Mary, Claudia and Laurie. There was no report. Then the squelch on El Paso’s radio was broken three slow times. Sitting tight. Nothing more happened.

At the CP Cahalan monitored a krypto call that excited Brooks and FO. Bravo Company’s honcho POW from several days earlier had agreed to lead that company to a headquarters bunker complex he maintained they had swept over twice without discovering.

“There it is,” FO said, smiling, relieved.

“Thank God,” Cahalan said. “They’re goina send Bravo back up that ridge.”

“Least it aint us,” El Paso said.

“I still think there might be a bunker complex on that knoll,” Brooks said cautiously.

“You heard the man, L-T,” Cahalan said wanting to believe the call. “Their hotel quebec is down by Bravo.”

“Don’t get your hopes up too high,” Brooks said. “Bravo still hasn’t found it.”

After an hour the squelch on El Paso’s radio was broken twice. Rover Team Laurie reported laconically, “Kilo india alpha one november victor alpha. Counted two seven moving november. Out.”

Cherry and Egan and Denhardt left Campobasso well after dark. The rain had not ceased. It was very dark. Egan led them at a slow walk. The move even to the close perimeter of their NDP was hard. They cleared themselves with the guards, radioed the LP and walked out erect. They made no sound. They moved slowly, Egan leading, Cherry laying one hand on Egan’s ruck following in the middle, Denhardt holding Cherry’s ruck at drag. No one spoke. No one coughed. No equipment rattled. Egan kept one eye on the luminous dial of his compass. Cherry counted their steps. Every few meters they froze and listened. Then they moved on. Twenty meters, forty, sixty. They froze. The LP should be to their left. Cherry keyed his handset three quick clicks to break the natural static of the radio at the LP. The LP acknowledged by repeating the signal. Rover Team Stephanie moved on. And on.

They came to a trail Pop had skirted earlier when he had led Egan and Cherry to the road. Egan dropped slowly to his knees. He felt the ground for a thin, rigid piece of grass. He found one. He lifted it to his face and brushed it across his nose. He brushed it against his pant leg, over the compass, on the ground. Egan hefted the grass blade in his right hand then spread prone, on his stomach in the trail. Cherry followed Egan down kneeling behind him in the muck of the trail, grabbed Egan’s left foot with his left hand. Denhardt slowly squatted behind Cherry. The team inched forward.

Egan brushed the ground before him with the grass blade before each movement. Very slowly he extended his right hand with the grass checking each inch of trail for booby trap trip wires. There was no rush. He had all night to cover only a few hundred meters. He retracted his hand then pulled himself forward the cleared one-third meter. Cherry and Denhardt crawled forward with him. Egan repeated the sweep. The trail was bare of growth because of heavy traffic. The mud was three-inch thick slime. It seeped into every opening in Egan’s fatigues, into all their boots. Somehow it was not uncomfortable. It was soft. It was no wetter than they already were. It even felt warm. Cherry felt very relaxed.

Where puddles inundated the trail Egan put the grass stalk between his lips and walked his fingers slowly through the water. Then he slid into the puddle and checked the next arm’s length of dark territory. Cherry continued counting. After every fifty movements he shook Egan’s left foot. After three hundred and fifty movements they ceased moving. The road, the smell of cordite, was directly ahead.

Jax’ skin was almost rotted through. Of that he was sure. His muscles were cramping from the cold and the hours of stillness. He was sure he would die of exposure. “Au this fucken way,” he whispered to Hoover. “Au this way ta die a nee-moan-ya.”

“My pecker’s freezin off,” Marko whispered over.

Earlier Jax had been more enthusiastic. When the L-T had asked him for the name of his Rover Team, Jax had cooed, “I’s be Jax, they’s my Jills; Jax en Jills goes up the hills ta fetch nine pail a mud; Jax come back, the Jills got sack; carryin nine pail wid gook blood.”

Rover Team Jill was the farthest east of any Alpha element and long into the night they seemed to be in the quietest locale. They had set up in a hollow in a bamboo thicket three meters from a narrow trail. They had left Campobasso on schedule at 1930 hours and had reached, found, their night position by 2100. For five hours they had sat still, cold, waiting. They had gone out with great anticipation and enthusiasm for the tactic, had gone with the expectation of a first-time fisherman, and with the same patience.

Jax could no longer control his arms, legs and chest from shaking. He was wet, had been wet for what seemed like forever. The hot dry interlude at resupply was forgotten. Jax’ teeth began to chatter. Hoover snuggled up to him on one side, Marko on the other. They each wrapped an arm over Jax’ back. The warmth felt good but it was not enough.

“Fuck it,” Marko said. “Just say fuck it. Don’t …”

“The fuck it doan,” Jax whispered wildly, standing up. “We gotta …”

At that there was an explosion perhaps thirty feet away. They froze, solidified like statues. Jax’ chillchatter vanished. The sound had been a loud pop, a giant explosive cork blasting from a bottle. POUAHK. A second mortar round was launched. Jax turned to Marko then siezed a grenade from his belt. “Frags,” he whispered. Hoover and Marko immediately grabbed two each. Jax stepped forward, one pace, two, three, to the edge of the trail. Hoover was to one side, Marko to the other. The sound of the mortar team chattering in Vietnamese came from their close right front. “Throw two, then hit it,” Jax whispered. “On go.” He paused to give them time. Then he whispered, “Go.” They cocked and threw.

Another mortar round was launched.

Jax, Marko and Hoover each immediately depinned and threw their second fragmentation grenade. Then they hit the ground. Marko’s first frag went beyond the NVA, Jax’ to the left, Hoover’s also behind. All exploded simultaneously. An enemy soldier screamed. The second three frags exploded. There was scurrying in the brush, there was the sound of a body being dragged. Then all was silent. Rover Team Jill lay perfectly still until first light. Jax smiled the rest of the night.

In the center of the Khe Ta Laou River valley nothing moved before first light. The NVA had called a halt to routine early morning moves. During the preceding afternoon and night they had been in contact five times with unknown elements of the American battalion that was stamping around in the hills and most probably sending a coordinated series of ambush teams into the valley on a one-shot attempt. All five contacts had resulted in North Vietnamese losses with no apparent American losses. The situation could not be serious. Americans never stayed in one area for long without building an outpost. They had not built one so they must leave soon. Sit tight, the NVA command ordered. Sit tight until tonight.

During that same pre-dawn Cherry had his last rational thoughts. Rover Team Stephanie had moved from the trail they had crawled up, into a tangle of debris, vines and bamboo. They spoke not a word. They breathed the smell of burnt explosive and the smell of blood hour after blackrain hour. Chill set into every bone. Egan took it in stride. He always did. His sense of easiness, almost casualness, permeated the others and they too relaxed. Denhardt breathed slowly, deeply. The war odor was pleasant to him. Stuck in that remote rotting valley of death one had either to accept the smell and be pleased with it or accept the smell and abhor it. Either way, sanity fled.

Earlier at Campobasso Cherry had been nearby while Brooks questioned the platoon sergeant. He had heard snatches of speech and had wanted to comment but he had not been invited into their circle. In his mind he now pictured Egan and him in serious discussion. Suddenly he found himself with Egan. They were at a CP, chatting softly, almost intimately.

Every day since they first encountered each other at Phu Bai Cherry and Egan spent more and more time together. They were now almost older brother, younger brother. Hadn’t Egan even called him Little Brother earlier that very day?

“Yer such a cherry,” Egan’s image laughed to the image of Cherry.

“I thought you were on the other side of that,” the Cherry-image answered firmly.

“A man’s got a right to have more than one opinion,” Egan whispered. “Goddamn, if I believed everything I’ve ever said I’d be so mixed up I’d be crazy.”

“Sometimes, yer such an ass,” Cherry joked.

“And yer such a cherry,” Egan retorted and he grabbed Cherry’s head and mussed his hair playfully. Then he said seriously, “Ya know, Cherry, all my life everybody’s been tellin me how nice I am and that kinda shit. And all my life I been tellin myself what an ass I am. Then I came to Nam. And I discovered I wasn’t a fuckhead. I discovered I was okay. Now everybody tells me I’m an ass. Cherry, yer a cherry ta life. People want you ta be an asshole so they tell ya when yer being an ass how good ya are and when yer bein okay what an ass ya are. It makes em feel superior. Fuck em. Fuck it an drive on, Breeze. It don’t mean nothin.”

“Eg,” the Cherry-image said lightly, good-naturedly, the way only the closest of friends can laugh during serious conversations, “Eg, you gotta live with people.”

“Fuck em all,” Egan said.

“Man. Man, you are doomed. Man, you are doomed to being a lonely person. Shee-it, when a dude can do everything for himself, when he don’t need anybody, he’s goina be lonely. Nobody can please you, Mister Egan. Nobody’s good enough for you. You gotta do it all yourself and that’s lonely, Eg. Lonely.”

“Yeah,” Egan’s image agreed. “But here, in Nam, here it’s alive too. You can’t trust somebody else with your security cause aint nobody goina look out for you as well as you. You remember that when I’m gone.”

Cherry dozed. He awoke in despair, in agony. Something from the very depths of his body was screaming. The sky hinted at becoming light. Cherry snapped his head toward Egan. The platoon sergeant was there where he should be. Egan nodded to the trail. Cherry looked. Something in his mind snapped. Cherry stared at the darkened rain-blurred scene. He stared at the carnage only feet away. Egan motioned for Denhardt to recon the trail to their east. Egan snaked through the grass west. Cherry continued staring. The sky lightened in imperceptible stages. Cherry’s body twisted. He snarled then laughed to himself. “Fuck it. Really don’t mean nothin. Drive on.”

Cherry rose slowly. He rose to full height and stretched. He threw his shoulders back, stretching out the night cramps. He arched his back, he wiggled his toes and fingers. He felt for his frags. They were in a pouch on his belt as was right. His rifle was in his left hand. He ran his fingers over it. He aimed the muzzle downward and slowly withdrew the bolt carrier halfway, draining any water which might have entered the barrel during the night. Noiselessly he let the bolt slide back closed and he shoved hard to insure it seated completely. Then he looked up again. They, it, was still there.

Cherry took a half step forward. He advanced without his ruck. He looked left for Egan, right for Denhardt, then stepped among it on the road. He laughed quietly, apprehensively. He looked up and down the road and he looked straight up at the woven canopy, beyond into the rain into the lighting sky into heaven. He half-stepped forward and he stepped on a half head, a half face. He jolted back nervously and giggled. An eye was looking at him from the mud. Cherry stared back. The eye looked at him. Cherry’s leg snapped out reflexively. He felt the eye pop beneath his heel. There were at least five bodies, perhaps six, strewn over forty feet of road. Cherry smiled. How could Egan have placed the claymores so perfectly? How had he known the first man would miss the trip wire allowing the squad to completely enter the kill zone? That cunning mothafucker. Mangled them all. Must have gotten em all, too, Cherry thought. No one left to collect their weapons. Cherry bent down and lifted a Soviet AK-47 assault rifle from the mud. A hand came up with it. A hand and four tattered inches of wrist and arm. He carefully pulled the fingers from the trigger guard. The skin was cold, stiff, slimy. The stock of the rifle was splintered. Cherry dropped it back onto the piece of hand and arm and maybe a chunk of abdomen.

That raggedy-ass mothafucker don’t look so bad, Cherry thought advancing to the next body. He unsheathed his bayonet and removed two NVA ears. As he hacked off the second there was movement at the corner of his eye. He spun and sprawled flat amongst the dead, aimed his 16 up the road, flipped to automatic and began to squeeze on an advancing blur.

“SKYHAWKS,” came an immediate whispered call. Cherry toyed with the idea of squeezing the trigger anyway. “SKYHAWKS,” Denhardt’s whispered call came again.

Cherry relaxed. “SKYHAWKS,” he whispered as Denhardt materialized from the mistdarkness. Cherry returned to the NVA corpse and retrieved the ears. “These are for Whiteboy and Silvers,” he whispered to Denhardt. Then he went back to the half head and cut the ear from it. “Here,” Cherry said. “This one’s for you.”

When Egan returned from his recon west he directed Rover Team Stephanie to police up the MA site. There were four AK-47s and an RPG launcher, ammunition, letters and documents. The boonierats split the load, Egan retrieved the trigger mechanism for the MA. Then they dissolved into the thickets to hide and to eat and to wait for dawn. “Wait til Pop hears of this,” Cherry said happily to Egan. “Pop’ll be just so proud.” Egan looked at Cherry and nodded.

Cherry ate a C-ration meal of Spaghetti and Meatballs in Tomato Sauce. He ate it ravenously. His stomach was still empty. He opened another can. This one was pork slices. Cherry plucked a thick firm slice from the can with his mud-crusted fingers. He jammed the slice into his mouth. He chewed twice, swallowed, jammed in another slice. He drained the juice from the can into his mouth then dropped the can beside the spaghetti tin.

Egan reached over and picked the cans up and signaled for Cherry to put them into his ruck. No signs of American presence were to be left by the rover teams. “Pack it back here to Campobasso,” Brooks had directed the team leaders. “Pack everything out that you pack in,” he had said. “Except your shit. Bury that deep and camouflage the spot.”

Cherry ate a B-2 unit tin of Crackers and Cheese and washed it down with water from the blood-stained blivet that had been Leon Silvers’. The pimples that had formed days earlier on his arms and legs and face and back and had then turned to sores and then oozing ulcerations were now filth-covered jungle rot. The sun and drying at the LZ on Hill 636 had accomplished little. The treatment had been too short and the patient had returned too quickly to the wet rotting valley floor.

Cherry did not care. He aped Egan, washing carefully in a puddle but it was for show, for camaraderie, not for cleanliness. He wasn’t concerned about the sores. They were beyond the point of hurting. “Like my shoulders,” Cherry would have said had he even thought of it. “My shoulders hurt like hell from the ruck at first but they toughened up. Now they don’t hurt at all. My skin’s the same. It’s getting tougher.” Indeed, Cherry was becoming callused hands, shoulders and mind. The wetness softened the calluses on his hands and shoulders and they rubbed off. The wetness had no effect on the calluses of his mind except to make them thicker.

Combining with the toughening of his mind were new abilities, the new keenness of ears, sharpness of eyes, the education of his nose to jungle smells. Cherry developed a new acuteness of these senses which allowed him to know the primitive world which extended all about him, to know it more quickly and more fully, he was certain, than any other boonierat, even Egan.

But Cherry did not think of these things now. They did not really matter. Cherry only thought of two things. He thought of eating and he thought of killing. “Let’s go,” he pleaded to Egan when Egan dawdled over his morning coffee. “Let’s set up another one. I got an idea just where.”

The MA Cherry set up under Egan’s watchful direction was similar to the first booby-trapping of the road beneath the cliffs except that it used only three claymores. It did not need more and they did not have an unlimited supply. Cherry picked the site. It was beneath the woven canopy of the road at a spot where the ceiling needed repair. “This’ll be a riot,” he told Denhardt. “Wait’ll they try to fix this one.”

Cherry worked as methodically as Egan and Pop had worked setting the first MA. He set and aimed the claymores from one point, in three directions. He hid the mines on the road corridor wall aiming across, up and down the trail. He imagined the enemy crew carelessly approaching the site, their security out, their work about to begin. Cherry set the trip wire in the canopy so it would be triggered when the repair team began reconstructing the roof. “Let em get in a good close clusterfuck,” he laughed.

“Oing douk mann cowy?” Doc tried.

“Ông duoc mahn khoe?” Minh repeated.

“Ông douk manh cowee?” Doc tried again.

“Da, Cām on,” Minh said.

“Ya, cam urn,” Doc repeated.

“Oh, that is very good,” Minh said. “Tôi lā Minh.”

“Tôi lā Alexander,” Doc said.

“Oh yes, very good,” Minh said. “Now, môt, hai, ba, bôn, nam, sáu, bay, tám, chin, múoi.”

“Mot, hi, ba, bon, nam, sow-oo, bay …”

“No, no, no. Môt, hai, ba. Ba,” Minh intonated. “Not baa. Ba.”

“Hey Man, I aint never gonna learn it. You say ba not ba. There aint no difference.”

“Yes, yes. Listen. Ba. Here, we shall write it and then say it.”

“Minh,” Doc said. “I gotta get these dudes up. Lazy fuckas. Half em still crashed.”

“We should write. Viêt, dó lá môt cách noí không bi ngat lái.”

“What’d you say?”

“That is a quote from Renad. ‘Writing is a way of speaking without interruption.’”

“No shit.” Doc chuckled. “Minh, you my main man. Here, eat this.”

“Daily-daily?”

“Daily-daily.”

Doc slithered from beneath the poncho he and Minh had strung eighteen inches above the earth the afternoon before. They had covered the sides of the hootch and one end with palm and bamboo scraps and had camouflaged the top with a tangle of bramble branches. After they had set up they had simply crawled in and rested and let the valley, the rover teams and the war go on about them. The whole idea of hiding an infantry company in a valley and breaking it into ambush teams was, to both Doc and Minh, insane. With the sounds of each explosion reaching their hootch Doc had squirmed out into the rain and had edged over to El Paso to find out what was happening and if he was needed. El Paso and the L-T had set up a similar though smaller rain shelter less than five feet away. Brown and Cahalan’s hootch made a triangle of the three. Each time Doc found El Paso, El Paso had nothing to report and Doc had returned to his hootch and rested. Restlessness came with first light. Minh and Doc traded words, English for Vietnamese, for half an hour. Then Minh began in earnest to try to teach Doc Vietnamese.

Doc looked at the sky in disgust. Rain. Fog and rain. His boonierats were melting. Doc shook his head. He stepped lightly to the rear of his hootch, relieved himself, then went to check in with El Paso and Brooks.

“Daily-daily,” Doc whispered cheerfully handing in two tiny white anti-malaria pills. “Up ya go, L-T. Hey, your boys soundin like they done a J-O-B las night. What the score?”

“We got at least ten,” El Paso beamed. “It’s like shootin tacos in a barrel a refried beans.”

“No shit?”

“No shit.”

“Nooo shee-it?”

“No shit, Man. I shit you not.”

“Shee-it!”

“No shit.”

“Shit, Man. I think you shittin me.”

“I shit you not, Bro.”

“Will you guys cut that shit out?” Brooks laughed and the three of them giggled. Doc shimmied in beneath their poncho with them and the three lay on their backs looking up at the damp plastic coated ceiling less than an arm’s reach above.

They were silent for a moment then Doc said, “No shit,” very quickly and the three of them burst into giggles again. “I gotta get Minh,” Doc said sliding back out into the rain. He stood up and walked the two paces to his hootch then returned and ducked his head in and whispered, “Sshheeee-yit.”

Soon there were four beneath the single poncho. They lay like packed sardines, not moving, not talking. Brooks was half outside on one side and Doc was half out on the other. After perhaps four or five minutes Doc and Brooks and El Paso whispered, starting very low and building to a whispered crescendo, “ssshheeEEE-YYITT.”

They found it hilarious and forced fingers into their mouths to keep from laughing loudly. Minh did not get it and they found that even funnier. “What is so funny about shit?” Minh asked seriously, a smile coming to his face.

“Don’tcha get it?” El Paso chuckled.

“No,” Minh said.

“No Shit,” Doc said and the four of them giggled.

“Hey,” Brooks called a pause to the laughter. “I want to ask you some shit …” The laughter became uncontrollable again. “Come on,” Brooks said. He was feeling better this day than he had for many days past. “Come on,” he repeated. “No shit.” Giggles, suppressed giggles. “Anybody want some mocha? I got a hot cupful.”

“Ooooh shit, that is hot,” Doc laughed grabbing the cup, spilling the hot liquid on Minh.

“Ouch!” Minh screamed suppressed, bolting upright, hitting the top of the poncho, snapping a line on the roof and caving in the head end which held a puddle in a swale. The water splashed onto El Paso’s laughing face.

“Augh fuck,” El Paso said shaking his head violently.

“Oh, now we goan from shit ta fuck,” Doc teased him but he did not laugh. The laughing was over.

Brooks, Minh and Doc moved to Doc’s hootch for the discussion. As he had with the others Brooks opened with the question, “What causes conflict?”

“Life is motion,” Minh said. “Life sways between plus and minus. You view this as conflict. Why?”

“I’m not imagining conflict,” Brooks defended his thoughts, his thesis. “It’s there. Personal, interracial, international. Jesus, Minh! We’re in the midst of a war and you ask me why I view it as conflict?”

“You have asked for weeks everyone the same thing. Everyone gives you an answer. You still ask. Perhaps you do not seek the answer. Perhaps you are more satisfied with the question. It is a good question.”

“Perhaps.” Brooks was thinking furiously, trying to make a connection.

“Yes, perhaps,” Minh said. “The ultimate reality is not static matter but the motion of physical existence.”

“Say that again,” Brooks said.

“Reality ultimately is not static matter but the motion of physical existence,” Minh said. “The most essential thing about life is that it is not static. If it does not flow, if you place emphasis on having instead of doing, you will miss the essence of life.”

“Wow!” Doc said rolling on his side to look at Minh. “Wow! That’s heavy Mista.”

“I have learned very much with Americans,” Minh said. “I have learned much by watching you and thinking about you.” Minh was gazing at the roof of the hootch, looking as though through it to a very distant point. “You Americans,” Minh said. “You have so much. You think you can do everything. You think you can control nature with your words and your theories. I think sometimes you miss the point.”

“Words are important to me,” Brooks confessed. “I want to find out, if, first, our thoughts control our actions. Then, if our thoughts are determined by the language we learn and finally, are the determinants of conflict, of war, built into the structure of our language. Can’t you see? If all that is true, we would be able to restructure human languages to eradicate war.”

“Oh, L-T,” Minh sighed. “You are more intelligent than most Americans but that only makes your plans more complex. You are like them all. You think you can do anything.”

“It can be done, Minh.”

“L-T Brooks, man does not control nature with his scientific theory or with his engineering principles or with his history or with words of any kind. All he does is seek to explain nature. We seek to know how it works. Perhaps to be able to forecast the future from the past. We can arrange elements but we are one with nature and perhaps nature has simply had us arrange the elements for her. Things happen. People die. That is the flow of reality.”

“Do you accept war, Minh?” Brooks was agitated. He tried to hide it by speaking even more softly than usual. He still sounded accusing. “Do you accept a war that has ripped your country apart for thirty years?”

“I can do nothing else but accept it. It is. Perhaps it is not all evil. We go to war. America sends her technology to my country and we learn and we will never again be so backward. Maybe this war is good.”

“Egan said something about that. He said technology only thrives in cultures where the religion and … what did he say? Wait one. Let me look.” Brooks flipped back through several pages of his notebook and scanned his writing. “He said some cultures are passive and believe a man must bend with the wind and flow with nature while other cultures are active. Active cultures have active religions and beliefs and think they can control their own fate. Industrialism only grows in active cultures for it requires those active thoughts as a base.”

Minh did not say anything for what seemed like a long time. Brooks and Doc remained silent. They listened to the spattering rain on the poncho above them and to the slight breeze in the vegetation. At a far distance, perhaps at the firebase, a lone helicopter was landing. Earlier Brooks had received the report and forecast. A storm had come in from Laos. The rain would last forty-eight to seventy-two hours. Then it would clear. The valley would remain in intermittent fog.

Minh broke the pause by asking Brooks what he meant by activist culture and activist religion. They discussed this lethargically for some time.

“No L-T,” Minh said. “You make a mistake. I am Taoist and Zen but they are not my religion. They are not religion in your western use of the word. Maybe my Tao is more close to being principles of consciousness. It is what I live by. How I see myself and people around me and nature around people. Occidentals have no knowledge of their principles. Your principles are based only on not dying. The most terrible thing ever to an occidental is to die. You will do anything to live a day longer. What may be worse than dying is living without dignity or without … I do not know how to say it in English … without Tao. You have moral codes and religious laws and civil laws imposed on you but it is unusual to find an American with principles of living inside him. All Vietnamese know this. There is nothing in your culture to lead you to develop your inside principles. That is why you require outside laws. We are just the reverse. Then Europeans came and conquered our land and brought us their true religions and their true gods and their god-made laws. Now we have that too.

“The problem with your active church,” Minh continued, still staring up through the poncho, “is that you propose to have all the answers. All you really have is a systematic format on which to pose the questions. Your answers are rhetorically achieved and predetermined from the format and thus are only true within the framework of your system. Your religion has no more meaning, no more real answers, than the Tao did twenty-five hundred years ago. And the Tao did not then and does not now have a rigid format or a firm construction so its answers were not and are not conceived in the asking. Do you understand, Sir?”

“That’s exactly it,” Brooks said. “That’s what I’ve been saying about war. War is predetermined from the format of languages and culture. If we could unstructure the language then restructure it on a less rigid format … see? War would not be conceived in our speech.”

They talked for hours. Brooks left several times. For two hours he was gone—over to FO’s lowslung hootch to study the maps of the valley and to piece together the intelligence reports from the rover teams and from battalion and brigade. Brooks consulted with El Paso and Cahalan. After each tactical consultation he returned to Minh and Doc. They talked to the hour where, beneath a rainsky, day and night are indiscernible.

Doc Johnson had been becoming more melancholy and contemplative all afternoon. “Yea, though I walk through this valley of the shadow of darkness and death,” he quoted the 23d Psalm, “I shall not fear, for thou art with me.” Doc looked at Minh and the L-T. “That mean somethin to me, Mista,” Doc said.

“Nor shall I fear,” Brooks said, adding a common boonierat paraphrase of the psalm, “for thy arty and thy B-52s are on call to comfort me.”

“That fucked Mista,” Doc said sadly.

“Yeah, I guess so,” Brooks said. “But we’re only a tiny part. Somebody else is running the show.”

“A man should control himself,” Minh said. “It is not the rightful pursuit of any man to try to control the life of another. And each village must be responsible for its own internal affairs. The provincial government must stop at the village gate and the national government should control only interprovince relations. No nation should control another.”

“You both educated men,” Doc said. “This makes me feel sad. I feel sad, Mista. My country fuckin with yours. I don’t know why. You tell me why?” Neither Minh nor Brooks answered. They had been over it many times before. “You know somethin, Mista? We can do most anything. In fifty years we increased life expectancy in America by fifty percent. That’s right. If we keep goin, average dude in the World in fifty years gonna live to one hundred twenty years old. We wipe out typhus, smallpox, polio, diphtheria. Why, Mista? Why? Like the L-T wanta know. Why caint we wipe out war?”

“I have a solution for my country,” Minh said.

“Well, what the fuck you doin here?” Doc asked harshly. “You belong in Saigon.”

“What is your solution, Minh?” Brooks whispered.

“No one,” Minh said staring straight up again, “no one will accept a national election of the North and the South with the winner-take-all result. But we could reunite at a very high level similar to your federal government over your state governments. We could still maintain a government in Saigon and a government in Hanoi. Then we would have a neutral federal national government in Hue. That government would stop at the next level down. We would have our harmony restored.”

At 0200 hours Rover Team Danielle spotted an enemy force approaching their position. The NVA were moving slowly up a medium-use trail. The point and slack each carried American rucksacks. The third soldier carried an American PRC-25 radio.

They all had rifles which they carried in tight against their bodies. The pointman advanced cautiously, raising and lowering a bulky tube to and from his face between each movement. It appeared to be a scope of some kind. Five meters behind the lead element were four soldiers, two pushing two pulling a small cart. The cart looked much like the market place carts of Da Nang or Hue with their bicycle wheels at the sides and their wooden traces. It was overflowing with supplies but in the dark neither Moneski nor Beaford could distinguish what comprised the load. They woke Gorwitz and Smith silently and pointed out the advancing enemy. The NVA were perhaps ten meters down the path. Rover Team Danielle had occupied an old NVA fighting position a meter off the trail. They waited. Moneski wanted the cart. He wanted to engage the unprepared cartmen with their weapons in the cart. Danielle waited. The NVA approached. Beaford’s hands sweated on his machine gun. The enemy squad used five minutes to cover ten meters. When the point was opposite Moneski he stopped. He put his weapon down and turned to the slackman and said something very quietly. There was a pause then they laughed quietly and proceeded. Beaford urinated in his pants. The cart passed. The laborers were breathing hard, forcing the wheels through the mud of the trail. Moneski waited until they were up the trail to a point where it bent. Rover Team Danielle opened up with two M-16s and Beaford’s 60. All four cartmen were shot and killed. The other enemy soldiers fled. They did not return fire. The rover team decided to abandon the cart. They backed out of their position and retreated to a secondary position they had chosen earlier.

An hour later Paul Calhoun of Rover Team Ellen killed a lone NVA soldier as the enemy rose from a riverwatcher position not ten meters from Calhoun, Pop Randalph and Jim Woods. Then Rover Team Laurie ambushed and killed three enemy soldiers next to the river. Pop Randalph’s second MA, set up between RTs Laurie and Ellen, killed two soldiers fleeing Laurie’s ambush. The night had settled down for only a short time when Cherry’s MA exploded.

“Get em all,” Cherry pleaded from his hidden muck-filled trench. “One for the Garbageman and one for Ridgefield. Get one for Silvers and … oh shit … get em for anybody.” Cherry moved to rise. He wanted to count the dead. Egan grabbed him, held him still. “I gotta see,” Cherry whined.

“I don’t wanta put ya in for a Purple Heart,” Egan answered.

They waited. They waited until half an hour after first light. Cherry fidgeted. His eyes were glassy. He had not slept. He rolled over and with his back to Denhardt and Egan he fondled himself. He thought of the stewardess on the flight from New York to Seattle who had been pleasant and he imagined her naked. Then he thought about Linda. His girl. Not anyone’s girl. She made him angry. Off to Boston. Off to New York. Philadelphia. They had never made love yet he could picture her naked too. He could see her fine legs and her soft muff. Cherry rolled his tongue inside his mouth and imagined it in Linda’s vagina. That bitch, he thought. I bet she’s screwin like a rabbit. I bet she always has. Been screwin guys left and right even when we were goin out. Never gave me none. Bitch. Cherry’s anger raised his excitement. Christ, he thought. I need a girl. I need someone to fuck. I got so much jizz stored up if I fucked right now I’d shoot so hard I’d blast her ovaries up to her sinuses. Oh, get em all.

Egan allowed Cherry to recon the MA site while he and Denhardt pulled security. They had killed three NVA soldiers. All three had been carrying rifles. One had had an old infrared-night scope. Later, when Cherry packed it back to Campobasso, FO identified it as French, vintage 1954. The scope amazed everyone in Alpha because they had all been led to believe the US Starlight scopes, technically and in concept, were very recent developments.

Brooks’ mind had been working all night. By first light he believed the NVA knew Alpha was on the valley floor and within range of the knoll and NVA guns, but he also believed the enemy did not know Alpha’s specific location any better than Alpha knew the enemy’s. No enemy troops harassed Alpha’s base, nor did mortar rounds impact on or near Campobasso. Bravo and Delta companies had both been hit. Firebase Barnett was mortared. Two Americans were killed, three wounded.

Brooks spent the day of 23 August much as he had spent the day before except that instead of talking he wrote. Occasionally he left his hootch. He spent an hour with FO and several shorter periods with each Doc, Minh, El Paso, Cahalan and Brown. Brooks spoke via krypto radio with the GreenMan. The operation was going well, and the GreenMan encouraged and advised him. When Lt. De Barti returned with Rover Team Joan Brooks briefed and debriefed him thoroughly yet he always returned to his notebooks. He wrote for the best part of ten hours and in that period he completed the rough draft of his thesis on conflict.

AN INQUIRY INTO PERSONAL, RACIAL AND INTERNATIONAL

CONFLICT—RUFUS BROOKS—AUGUST 1970

We think ourselves into war. The antecedents are in our minds.

Conflict, major conflict, does not just happen. It evolves. It may explode over a particular incident but the tension evolves leading gradually to the incident and the explosion. The elements of any conflict, whether it be between individuals or between nations, must form, grow, approach, collide and ignite. Let us here explore the causes and dynamics of conflict and of ultimate conflict—WAR.

Our world is coming apart and it is imperative that we go one step farther and develop a new perspective about, and response to, conflict. Conflicts are actions. Conflict is active disagreement, in its final stage violent disagreement, fights, riots, wars. Here we must set a premise—action, all human action, is preceded by thought. The argument can then be drawn, if thought precedes action then thought precedes conflict. Let us explore the thoughts, and the origins and dynamics of those thoughts, which lead to conflict.

EXPLORATION ONE: The roots of conflict and the expansion and escalation to violence grow from our competitive instincts and are accentuated by our language patterns. When we get into a conflict-compete situation we accentuate the differences in order to strengthen our position. Why? Is this innate in man or is it a part of our mythos, a culturally transferred response handed down from generation to generation? Is the mechanism for transfer language? Written and spoken? What elements in human languages cause us to think ourselves into war? What causes us to perceive a given situation as a conflict situation? What forms our character? What passes xenophobic responses?

LANGUAGE: Thought structured by language. And whose language? English. The white man’s language.