Chapter Three

Theatre

In the Beginning

My first two appearances on stage could have put me off acting for life and, ever since, I’ve probably just being trying to make up for them.

Out of all the children in school I was specially selected to present our Reverend Mother with a posy of flowers at a farewell ceremony before she left for a sabbatical in France. During the ceremony I had to climb the stairs to the stage with the posy, make my way to where she was sitting and, having presented the flowers to her with a little curtsey, bid her bon voyage. How hard could that be?

Well, quite hard when you’re only four years old, actually. Trying to retain two words of French when you’re that small is like having to learn the entire canon of Shakespeare, and it really didn’t help that said posy was not a posy at all but a bunch of gladioli that matched me in height. I got rather fussed about the whole thing. It wasn’t helped by the fact that Didi and all her ‘big girl’ friends were watching me and smirking. Under the weight of all the flowers I tripped on the stairs and, by the time I reached Reverend Mother’s chair, I’d forgotten my line. I promptly burst into tears in front of the whole school and hid in her voluminous black skirts. Let’s just say it wasn’t one of my finest moments on stage.

The next ghastliness was playing Chanticleer the cock, a minor role in the nativity play. My mother had sewn a jagged bit of red felt onto a balaclava to represent wattles. The felt flopped over and the hat was so big I couldn’t see properly. Maybe that’s the reason I’ve been so fussy about my costumes ever since. There were no floppy wattles for Sable.

I think I was 12 when I conned my way into the National Youth Theatre. My friend Roz and I went for an interview in one of the big white houses in Eccleston Square, near Victoria Station in London. It was number 22. I can’t remember exactly how old I was, but I remember the address. Funny, the things we remember. We said we were 15 and I got in, Roz didn’t. She said her favourite actor was Alfred Findley; I managed to remember his name was Albert Finney. They said I was too late to audition for an acting job so would I like to do admin or elecs? Since I hadn’t a clue what either of those was, I plumped for elecs and hoped for the best. I got a job helping work the electrics board at the Scala Theatre for the summer. Left in charge for five minutes, I managed to fuse the board and cause a blackout in the middle of a scene from Richard III when a blackout wasn’t needed. Neil Stacey was playing Richard and I had a crush on him. He was very kind about the blackout; it was the only time he spoke to me.

That wonderful actor Kenneth Cranham was friendlier and used to share his sandwiches with me. Years later, in 1979, we’d do The London Cuckolds together at The Royal Court Theatre. We were also at RADA at the same time – he was in the year above me. We had supper together a few months ago when we happened to be in the same city. It’s good to know people for over 50 years.

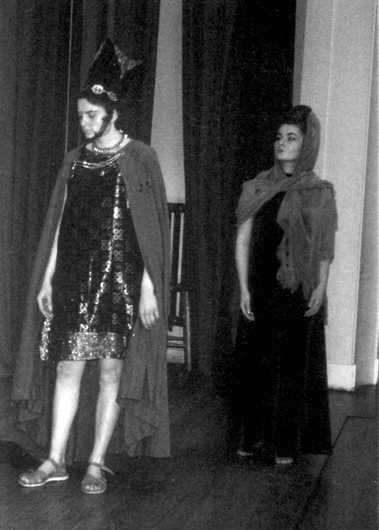

I only performed in one school play: Sophocles’ Electra. Miss Iliff was in charge of Drama. Her brother Noel taught me radio technique at RADA. They probably came from a theatre background. I was offered the part of Chrysothemis but I didn’t want to do that. ‘What’s the name of the play?’ I asked. ‘Electra? I’ll do that then.’ Hey, if I was going to have to stay in after school and not get to go out dancing I might as well play the big part. I got it, and became obsessed with the role: her plight, her revenge, the tragedy. I should have known then that I’d become an actress. My sister Didi says she’s still waiting for me to do something better.

Me as Electra – glad I wasn’t playing the boy

I left school after taking only Art and English A Levels, and went to Paris to study mime with Etienne Decroux. Decroux had taught Marcel Marceau, but if you asked him about Marceau, Decroux would just pull a long face and say, ‘Il est mort; il n’existe plus’ – ‘he is dead; he no longer exists.’ This was because Marceau had used props and had become what Decroux considered commercial. Serious stuff this mime business. I was entranced for a few weeks.

While in Paris I supported myself by working as an au pair, but the family’s maid took a dislike to me. Quite rightly: I was a terrible au pair. One day she threw a boot at my head and I was given a lot of Chanel No. 5 and sent back to England.

I went up to Liverpool to visit my boyfriend at the time. He’d just got a job with the newly established Liverpool Everyman. It was 1964 and Liverpool was happening. The city was alive. It was far more exciting than anywhere else. The Beatles were just one of many bands who, along with singers and beat poets, had made the city into what the poet Allen Ginsberg thought was the centre of the creative universe.

When I arrived, the company’s directors, Terry Hands and Peter James, were auditioning for Carlo Goldoni’s 1743 play, The Servant of Two Masters. It just so happened they were looking for a juvenile lead. I still remembered a Juliet monologue from Romeo and Juliet. I’d learned it for my English O Level.

At every stage of my life I’ve found myself in the right place at the right time – always at the centre of where the energy of the moment was percolating. Without any acting training I auditioned for the part – and got it.

I fell in love with theatre; my passion and openness for learning carried me. I learned on the job – from Terry and Peter, and from the rest of the company.

As well as The Servant of Two Masters, we were doing Shakespeare’s Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 and Macbeth, and Kenneth Grahame’s Toad of Toad Hall. It was the start of my career as an actress. In a review in the Liverpool Echo I was called ‘the girl with the golden glow’.

I’ve treasured that review ever since.

I’d been in Liverpool for nearly a year when Terry decided not to cast me for their next production, Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. He said I didn’t have the technique to do Wilde. I’d learned as much as I could with the company, and gone as far as I was able. Terry suggested I audition for RADA. It just so happened that John Fernald, RADA’s Principal, was visiting the Everyman. After he had seen the show that night, Fernald asked me: ‘What have you done before?’

‘Nothing,’ I replied.

‘What are you going to do next?’

‘Terry says I need technique and should go to RADA.’

‘Then you had better come down and see me,’ he said, looking over at Terry.

I did.

Being a student at RADA in the Sixties was a perfect time to be there. The world of theatre was going through a phase of growth and change. When we weren’t making it ourselves, or talking about it, we were going to see it. I was passionate about the theatre. I went to see anything I could. There was so much innovation. Through his Poor Theatre – and Theatre Laboratory – Polish director Jerzy Grotowski was revolutionizing the way people looked at, thought about and experienced theatre. I managed to get a ticket for a Grotowski production, on one of the rare occasions that he was actually in England, and turned up at the venue only to be led to a van and then taken on a magical mystery tour. Eventually we were taken to a basement where we sat, very uncomfortably, for three hours of Shakespeare in Polish. I also remember being amazed by it.

Closer to home, the British director Peter Brook was experimenting with using improvisation to create theatre in innovative ways. I remember, one evening, participating in an event he led at the Roundhouse in Camden Town. Audience participation has never been high on my list of comfortable activities, but it was exciting nonetheless. Experimental theatre was high art and a must-do for a drama student, as was queuing all night for tickets for Olivier’s Othello when the National Theatre was at the Old Vic. There were a lot of great actors and great theatre. I remember being entranced by Geraldine McEwan in Georges Feydeau’s A Flea in Her Ear.

The theatre’s a sacred place for me; it always has been, and it’s never stopped pulling me back for more. It had been its theatre of rituals that had drawn me to Catholicism when I was a child. There’s little glamour involved in performing in the theatre, though. It’s hard work – and touring with a play is the hardest work of the lot.

I get nostalgic remembering the way theatres used to smell – greasepaint, sweat, cheap disinfectant and dust. The smell I miss most is size. It was used to prime canvas backdrops before painting. Fresh size meant fresh backdrops, a new production and an opening night; good luck cards slipped under dressing room doors, nerves and last-minute adjustments. Actors’ sweat has a sharp smell: adrenaline. Adrenaline’s very strong and addictive. I keep being drawn back for more.

The Harsh Reality

There’s something quite stressful about Mondays on tour. First of all you have to find the theatre. I don’t know why actors are always trusted to turn up. I’ve always envied pop stars their tour buses, and love the way a car arrives for you when you’re working on a film. In theatre there’s no such luck – you spend a lot of time buying train tickets and studying Google Maps. You go in and do a sound check, have a try out and a walk through – you familiarize yourself with the stage. Then I prepare my dressing room. I have a collection of sentimental things that I always put in my dressing room. There’s a beautiful lace pillow case that I lay my make-up out on and there’s my dressing gown. It’s seen so many productions it’s nearly falling apart, but I won’t throw it away; it’s my lucky dressing gown – we’re a very superstitious bunch, us theatre folk.

Once my little home is set up I make sure I know my route to the stage. I’ll make sure my props have been laid out on the props table and that my wardrobe is where it’s easiest for any quick changes. It’s a new space so there’s a lot of organizing and finding out to be done. Then we get to do the show. After that we usually meet ‘Friends of the Theatre’. Then suddenly you’re alone. You haven’t been to your digs. You probably don’t know where they are. You’re all by yourself. You haven’t got water, you haven’t got flowers, and you haven’t sorted out anything to eat. Grabbing the sandwich left over from tea time, with too many bags in your hand you click off the light with your elbow, close the dressing room door and go off into the night. There’s no glamour and it’s not much fun after the show on a Monday.

Chances are on Tuesday morning you’ll wake after having had a rotten night’s sleep because by the time you got to your digs you couldn’t work out how to operate the heating and hot water. I always travel with a hot water bottle when it’s cold, in case I can’t sort out the heating. I prefer to be self-catering and not stay in a hotel. If you’re in a hotel the restaurant will be closed by the time you get back and the most you would be able to do is charm the porter into rustling you up a sandwich – another sandwich.

On Tuesday, if your name is above the title on the poster you’re probably up bright and early to do a local radio show – because the circus is in town and you’re part of the elephants’ parade. It’s certainly not all free time and just the show in the evening. You’re probably going to have to do an interview for the local paper for next week’s theatre and then you might have a little bit of rehearsing to do, as last night’s show didn’t go quite right. There was a hitch on your entrance when the door stuck because the stage is on a different rake and the set had gone up just before the show, as if by magic.

One of the best tours I ever did was in the Middle and Far East for the British Council. I was playing Olivia in Twelfth Night; Judy Geeson was playing Viola. They’re not huge roles so we got to do a lot of sightseeing. Imagine playing Shakespeare to Tibetan refugees in Kathmandu. They didn’t understand a word and laughed in all the wrong places. It was a lot of fun. I’m told I’m the only person ever to have asked to plug in their heated hair-rollers in Kathmandu.

With Judy Geeson, rehearsing Twelfth Night

Sometimes the matinee will be on a Wednesday, which means you haven’t yet had time to take a breath. I love matinee audiences. They’re usually old and, I always say, a standing ovation from an older audience is when they clap with their hands higher than their hearts. They’ve seen all the touring plays and are the most theatrically educated audience of the week. I really appreciate the effort made to get the bus, struggle through town and turn up.

On Thursday you might get to the cathedral or to the local art gallery. Chances are, though, you’ve got to do some repair work on yourself or buy new tights, get your nails done, get your hair washed or whatever it is that needs doing.

By Friday night it feels like you’ve been living in your digs for a year. I call Fridays ‘Reluctant Husbands’ Night’. It takes a lot of energy to keep those poor men interested, or even awake, after a long week at the office.

Saturday morning you have to pack up and get straight to your next digs by lunchtime to get to the theatre for the matinee – putting your suitcase, to carry on to the next venue, wherever the company manager tells you to. The two shows on a Saturday fly by and are generally fabulous fun. You know the theatre, you know the backstage crew and you know where the microwave is for a snack between shows. By Saturday you own the space. The dressing room you’ve taken over, which looks as if you’ve been living there for a year, has to be packed up during the show. By Saturday night when you leave the theatre, giving in your tenner to say ‘thanks’ to the man on the stage door for being nice, you’re very tired. Depending on whether you have a long way to go, and if it involves travelling from Edinburgh down to Brighton, you might not get Sunday at home. You might have to go straight in and do digs, or you might just manage to get home and push your front door against a pile of mail.

It’s hard and lonely work. A famous drummer friend of mine used to say he got paid to tour and did the drumming for free. I feel the same about my work – it’s got enormous highs but, along with those, corresponding troughs. My life’s been like that, too, and I feel blessed.

Rituals

I love rehearsals. They’re an opportunity for a special kind of playing. It’s when everything’s a possibility. Ritual and theatre go hand in hand. Playing is the ritual of the imagination.

When I come into the theatre before a performance I have a ritual for settling myself in and leaving the energy of the day behind me. I wander around in ever-decreasing circles; greeting people, doing what needs doing, sorting what needs sorting, round and round until I’m by myself in my dressing room. Just like a dog does before it can lie down. It takes me time to shake off the day. I can only get into character if I get rid of my day and get rid of me.

The sacred moment of opening a new script is a ritual, too. A new script really shouldn’t be flicked through for the first time on a bus or the Tube. Of course, later it’s going to be in my handbag and constantly rustled with, but the first reading is very important. That is, until you get to episode 147. At that point you just flick through the pages, saying ‘bullshit, bullshit, bullshit – oh, my bit…’

Some jobs you take for one reason and then you suddenly get involved with the whole thing on a different level and another reason emerges. I’ve made a few pretty dire films, but I got to go to Budapest, I got to live in Paris, I got to work with some fabulous people and I got to play.

The ritual of cleansing after a performance is very important. Some actors think it’s only possible in the pub. The thing is, the body can’t tell the difference between acting and reality. Whatever you’ve gone through on stage in the theatre is as real to your body as if you’d gone through it at home in your front room. You have to be very careful what you do with yourself after you’ve finished a performance. The trouble is it’s late at night so the swimming pool and the sauna are probably closed, and you can’t get a massage, so what do you do? Go and eat or drink; not a good idea late at night. It can be hard coming down after a performance – very hard. It’s easy to have a dark night of the soul after a performance, and on a daily basis. It’s when the drinking to oblivion often starts. I don’t drink – I never have. If I’m in the UK I usually phone America because they’re still up. In the past I’ve gone roller skating and dancing – lots of dancing. You don’t want to talk, chances are you don’t really want to think, you just want to come down. Sometimes I spend an inordinate amount of time in the ritual of taking off my make-up.

Beyond the Fourth Wall

I love theatre when it’s alive – when I can feel a synergy between the actors and the audience. Pantomime is perfect for that. When Jude, my grandson, was six years old I played the Wicked Queen in Snow White. I wanted him to be able to see me in something he’d enjoy. It was the first time I’d done pantomime and I loved it. Unfortunately we forgot to explain the rules to Jude and he got really upset when everyone booed me. The first time it happened he stood up and shouted ‘No!’ After the show I explained that booing for baddies was their clapping. When he came to see the show again he was the most enthusiastic boo-er in the audience. He’s going to look after his ‘Glamma’, that boy. He’s never forgotten my Wicked Witch. I asked him what he thought after he came to see me play Maria Callas in Master Class. ‘Hmmm,’ he pondered, ‘I think that was better than Snow White.’ My Maria Callas did look a bit like a wicked queen.

Panto is hard graft, two shows a day, but it’s a lot of fun. You’re free to acknowledge the audience and play with them. A baby starts crying: ‘Bring it here and I’ll wring its neck.’ You can come forwards and talk to your audience. Restoration comedy’s like that, too. There’s no imaginary fourth wall that you pretend the audience aren’t behind.

If you’re doing a Harold Pinter play, the audience isn’t there. They have to exist for laughs and timing, but beyond that they’re not there. They’re not part of your experience on stage. You’re just talking to other characters in a living room; there’s nobody watching you.

Harold Pinter’s meant to be quite highbrow so there’s no playing allowed, but the naughtiest actors always find a way. In 1970 I did two Pinters in the West End, at The Duchess Theatre: The Basement and The Tea Party, both with Donald Pleasance and Barry Foster. Donald was always trying to make me laugh on stage. His character wore glasses and he played one of our scenes with his back to the audience. On one occasion, as the lights came up on stage, there were two grapes where Donald’s eyes should have been. I tried to get him back but it was very hard – he was utterly concentrated. Then, during one of our performances when I was doing a staged leap, the crotch in my trousers ripped. Donald was shaking with laughter.

In the Sixties everybody had to take their clothes off at some point or other, even for Harold Pinter. There was a low-lit scene in which I had to undress and get into bed with Barry Foster. Then the set revolved and the next scene was me building a sandcastle in a bikini. While we were in the bed, looking like we were doing other things, Barry was helping me on with my bikini – only one night the bikini wasn’t in the bed. I had to do a quick change in the wings, get back onto the revolving bed and straight onto the beach, lights up. I remember sitting on that beach building a sandcastle wondering whether my bikini was on straight. Without the fourth wall I could have played that completely differently.

When Ken Cranham’s wig fell off during a performance of The London Cuckolds, I started laughing. It took away any discomfort or embarrassment the audience might have felt and they started laughing, too. That made Ken behave very badly. He started putting his wig back on upside-down and back-to-front until we were all in hysterics.

When I did The Rover with Jeremy Irons for the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1988, we had a similar moment. Jeremy did something that made me giggle. I can’t remember what: a naughty wink, or a funny look or something. I told him to stop and the audience started laughing. Once they started, I couldn’t stop. I was laughing so much I had to go and wipe my eyes on the curtains upstage. The audience adored seeing a film star and a television star enjoying being on stage together, and really cracking up. They felt that they were a part of something completely original, and they were.

If you laugh and the audience sees what you’re laughing at, your laughter will make them laugh, then their laughter will make you laugh even more; you can go on forever. It is great fun, but you’ve got to be very careful because you have to be able to pull the play back. It’s real laughter, and it’s a real moment. One moment the audience is just watching a play, then suddenly they’re a part of the play, and everyone’s wide awake.

Like Pinter, Noel Coward’s plays happen behind the fourth wall. In 1991 I played Rupert Everett’s mother Florence in Coward’s The Vortex at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles.

After the production finished I took a trip to Sedona, Arizona. I wanted to spend some time in a terrestrial vortex. Sedona is known as a sacred site and also as the location of vortices of spiritual energy. It’s set in quite an unusual and stunning red rocky landscape, in the highland of the Arizona desert. The red sandstone is totally unique to that area. One morning while I was meditating, sitting on one of the red rocks, the sun suddenly disappeared and I felt cold flecks on my skin. I opened my eyes. It was snowing, but only on the rock that my friend and I were sitting on. After a minute or two it stopped as suddenly as it had started. Then the sun came back out again.

Paid to Play

All through my life I’ve been tantalized with reminders of what happened on that rooftop at RADA. Very occasionally, when I’m on stage acting there is a perfect moment. If you stop and think, ‘This is a good moment,’ you’ll dry up on the next. You can only acknowledge it after it’s happened. There’s an experience of energy and communication; something happens. It’s about the synergy between the actors and the audience in the theatre.

RADA prepared me in so many ways for my career as an actress, including the experience on the rooftop. At the time it was another amazing new experience in a life that had been fuelled by new experiences. I put it in my medieval suede bag and it’s always been there, casting a glow over my life.

Theatre is its own kind of magic. Hamri, a wise Moroccan expert on magic, told my anthropologist boyfriend Bernie:

In the early human times there was magic everywhere, then over the millennia as mankind became civilized, magic declined and became ritual. Now in the modern world all that is left of true ritual is the theatre.

There’s nothing fantastical about make-believe; fantastic, yes – because believing is three-quarters of the way to achieving. I don’t have fantasies, I just make plans. I think of something fantastical and then I plan how I can make it happen. Everything begins as an idea, as a thought that bubbles up from the imagination. And being able to play, allowing yourself to play, exercises the imagination. The creative self is the God-self, born from the imagination. To create is to conjure an idea into existence; it’s magic. Being a creator is not playing at being God; it really is drawing on that God-self we all carry within.

I’m exceptionally lucky – I’m paid to play.

When I was in The Colbys I remember Charlton Heston and me injecting magic into some very dull scenes. Never mind the fact that the peripherals of the show were all about gloss, we still cared that its content should have a spark of magic. That great star Charlton Heston was a grafter, and he had real integrity. I’d go up to him, and he’d say, ‘Oh dear, I see the fingers are going,’ because my fingers wiggle around when I’ve got ideas. And I’d say, ‘Chuck, I’ve got this idea, because this looks rather bland the way it’s been written,’ and he always listened. We’d add subtext and superimpose meaning onto dull scenes, for the fun of it and because it made it a richer experience to do and to watch. As a rule, technicians – the chippies and sparks – don’t bother to hang around the set during filming. They do their job, and then clear off. But when Chuck and I had a scene and the First Director called, ‘Quiet on the set, we’re ready for a run-through,’ we’d gather an audience. They knew they’d get to see a little bit of theatre because we cared enough to want to create some magic.

It’s a very interesting thing not to kowtow to an audience, but to woo them without being a whore; to gather them up. It’s an art. It’s usually about the cast working together, unless you’re the main focal point on stage. When I toured Master Class in 2010–2011, I had sole responsibility for gathering the audience and taking them with me. The play’s set inside the Juilliard School of Music. It’s based around a master class being given by the great diva Maria Callas. For two hours, Maria talks to the audience as if they are Juilliard students. It was an extraordinary experience. The way I would woo them, the way I would gather them was different in each town. In Cheltenham, where everyone seemed to me to be so fragile and insecure, I had to be rather gentle and encouraging, whereas in Brighton the audience just adored Maria flagellating them!

My preparation before going on stage is sacred, and silent. Some people natter; I don’t. I absolutely have to zone in. Immediately before going on I rub my hands together until I feel the energy all around myself, and then excitement. Then I just say, ‘Let go, let God.’ It’s a ritual I’ve always done. It’s all about me getting out of my own way; I get out of my way to let the higher power come in and guide me. I let go and let God.

Once on stage you have to be truly in the moment, following each one as it comes to pass. There’s no living in the moment quite like there is on stage, apart from, perhaps, childbirth. If you’re thinking ahead, you’re mucking up. If you’re doing a post-mortem about what went slightly icky a moment ago, you’re mucking up. It’s like skiing slalom – like downhill racing. You can’t think ‘I’ve just flicked that post’; you have to think, ‘I’ve got to do this one and this one and this one.’ With ‘let go and let God’, you are released to be in each and every moment of the performance, conscious and awake to its unique magic. If I didn’t do this I’d be nervous, ego-ridden, fixated on wanting to do well, and fearful.

You can apply it to any situation that demands some kind of performance. If you’re going for an interview, or to an important meeting, it’s the only way to be. As long as you’ve done your best to prepare. After all, you’ve got to do the work – this isn’t about expecting God to do it for you. If you’ve done your preparation, take off your mental pinny, wash your hands and say, ‘Let go, let God.’ Just be in the moment. Only put in the energy that each moment requires. Don’t try too hard. Trying too hard is trying too hard. Trying too little is too little. Just be there. If you’ve done the work, just being there is enough.

Charlton Heston once said to me, ‘We’ve got the best job in the world, but don’t tell anyone. They’ll all want to do it.’ And I can remember Kenneth Cranham breathlessly exclaiming, as we came off stage during a performance of The London Cuckolds: ‘Oh Steph, this is better than sex!’ It’s true; it can be a lot of fun – as well as hard work. And it’s not just actors who have licence to play.