Chapter Five

When Kids Have Kids

Phoebe

We’d arrived at the hospital and my contractions were happening every three minutes. I’d brought a nightie, a Mars bar and my sewing kit. I didn’t really think this was it – I still had three weeks to go. Suddenly there I was, being hideously shaved by the roughest nurse, who could have worked for the Gestapo. I dragged my husband John into a bathroom, locked the door and got into the bath. ‘Give me a cigarette,’ I demanded. ‘This is ghastly.’ I had to regroup, to stop the hospital taking over. They seemed to think they owned me, and I wasn’t going to let that happen. This was our child and my birth experience. John went rushing off and bought tons of freesias. I was deep-breathing to the beautiful smell of flowers. It was completely magical. It was a perfect birth.

The next day was God-filled. A nurse found me weeping and asked if I was all right. ‘Oh, yes,’ I said. ‘I’m more all right than I could ever imagine being.’ God was golden in my heart and in my soul. I was weeping with gratitude for my beautiful child. Phoebe was so perfect. Everybody else’s baby was so ugly. I felt sorry for them. I didn’t know that’s how all new mothers feel.

Phoebe had been born on 29th December. On New Year’s Eve I was sitting with some other mums on our rubber rings. We were at that bad time – third day in – when the glory’s over and reality’s kicking in and you’re very sore and your milk’s coming in and it really isn’t a good feeling. John, his brother and my young nephew bribed their way with champagne to the fifth floor of the hospital. They’d brought a crate of the stuff. ‘Hold on… you can’t… Oh, Happy New Year!’ And in they came to this diverse group of mums and babies, and got us all completely merry. We had thought no one was going to be bringing in the New Year with us. Everybody else’s husband was off at this party or that. We had a great time, and the next day all our babies slept for ages.

We brought in 1975 very well. Anyone capable of instigating such fun is bound to be trouble.

That was John.

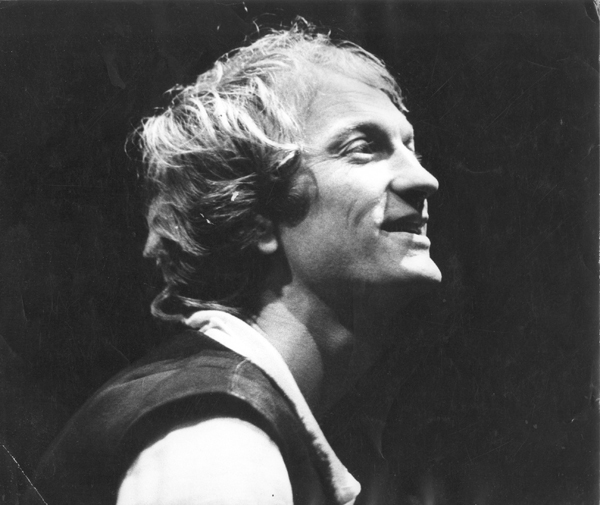

He and I had been a sparkling couple. We’d raced fast. We had a Jaguar XK150. He’d played Mercutio in Franco Zeffirelli’s multiple-Oscar-nominated film Romeo and Juliet. I’d already starred in films with Marlon Brando and Ava Gardner. We both loved to play. He had his flying machine and I had my doll’s house. We played like kids. Regardless of the time of day or night, we went with the game of the moment. We’d been to A-list parties but decided we didn’t like that life, and had taken our vows, made a home and started a family.

John

I first met John McEnery when I was 17. We were both working at the Liverpool Everyman Theatre. He was 21 and one of their leading actors. Once, while I was at The Everyman, John had taken me out for a bowl of soup at the local greasy spoon. I’d found myself rather stuck for things to say. He was this leading man, on the cusp of great things – soon after he’d be invited to join the National Theatre. One weekend we’d all gone to the Lake District for a break. John arrived with a girl from London. She had a Vidal Sassoon haircut and a kitten; very sophisticated – very Chelsea. I was just a wardrobe assistant playing juvenile leads.

It was seven years later when I got a part in Shakespeare’s The Tempest at The Nottingham Playhouse that I met John properly again. He was playing Ariel. Playing a spirit totally suited his mercurial nature. My friend Marsha Hunt used to call him ‘John McMercury’.

When The Tempest finished its run, John and I were cast to play opposite each other in The Playhouse’s next production: Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming.

Rife with sexual tension, The Homecoming is more about what’s not said between its characters than what’s said. The atmosphere on stage was electric between us. John and I took that off stage as well. It was intense. We were on fire. We became inevitable. We were soon living together.

John was vibrant, charismatic; full of life and brimming with energy. He was a very striking man to look at: blond hair, piercing blue eyes, a tall and slender frame. Around John you always had the sense that something quite unexpected might happen. We danced on an electrifying high wire.

And then there was his talent. I defy any woman not to fall for a man who exudes it. In terms of fame and fortune, John was devoid of ambition. In terms of his craft, he shone with a passion. Every performance was packed with everything he had to give, no matter how big or small the role. To watch him on stage was to watch a master at his craft.

And more – he was unpredictable. That was exciting. He was the first person I’d met who could react as fast as I could. The only trouble was, there was no thought between the idea and the action.

There was also a shadow of misery cloaking him, with an underlying difficultness I found both intriguing and challenging. Foolish woman that I was, I thought I could save him.

I loved this man – this totally irresponsible, incorrigible man.

We went to Tunisia. It felt like a honeymoon. John asked me to marry him and I said ‘yes.’

Back in London we arranged our wedding for three days later. My sisters Didi and Jenny and my brother Richard were living abroad and couldn’t arrange to be back in England in time. My father said he was playing golf and couldn’t get out of it. It didn’t matter. Mummy came and wore a big hat. All we wanted was to get married.

The day before the wedding, while we were shopping for strawberries and champagne for the reception, John asked me what I planned to wear. I hadn’t given it any thought. He went missing for the rest of afternoon, returning three hours later with a dress and a pair of shoes.

I’d never seen a dress quite so beautiful and extraordinary. It was a very simple tunic of two layers of white cotton. If you pulled the top layer up, it could be worn as a veil. It was unique and of its time, and very me. I was amazed that my husband-to-be could get it so right at a moment’s notice. I couldn’t have chosen a more perfect outfit. He wore one of my white silk shirts.

That was John.

Our friend Andrew McAlpine, an incredibly gifted art director, made me a bouquet of magnolia blossoms, and my two King Charles Cavalier Spaniels stood in as bridesmaids. My first dog, Amoreena, had been a gift from Michael Winner and Marlon Brando when we’d finished The Nightcomers. When she had puppies I kept one and called her Minnie. On the day of my wedding, with their leads and collars adorned with flowers, Amoreena and Minnie scratched their way through the service.

During the reception the reality of what we had committed to hit me. This was for real, it wasn’t a game. It was for life. To me, that was really important.

John’s wedding ring accidentally went down the drain the day after we were married. ‘I never did like wearing rings,’ was all he could say.

That was John.

Soon after we were married I became pregnant. I was delighted. The thought of motherhood and children hadn’t crossed my mind before I’d fallen in love with John. When that happened, my values changed. Now all I wanted was a family. My career suddenly meant very little. Even so, I decided to change agents so I could be represented by the same one as John – thinking it best if one person was in charge of both our careers and working lives. So began a long, for-richer-or-poorer, for-better-or-worse, till-death-us-do-part relationship with the brilliant Maureen Vincent at United Agents. It’s outlasted my other marriage by 30 years.

I was just under three months pregnant when John and I were cast to play the roles of Hamlet and Ophelia in a production of Hamlet at the Edinburgh Festival. But my pregnancy ruled me out of playing the Prince’s deranged, sickly and erstwhile love interest. It was decided I should play his other love interest, Gertrude – his mother.

At the beginning of the play Hamlet berates Gertrude for having married his uncle so soon after his father’s death. During rehearsal, and in character, John pushed me and I fell. I had a miscarriage and spent three weeks in the Royal Infirmary. We both blamed ourselves for what had happened – vain, uncompromising actors, putting our art above all else. It was a painful lesson.

Months later we were in Scotland again, staying with friends. On the day of our return to London I asked them to take a picture of us standing in front of John’s Jaguar.

‘Why do you want a photo?’ they asked.

‘I just do,’ I replied. I knew I could feel new life inside me. I was right. Phoebe was already waving.

Despite the Gestapo nurse but aided by John’s flowers, the birth went as smoothly as I could have wished. When the baby was crowning, just beginning to come out, John was so excited he said, ‘Look, it’s coming!’ and pushed my head down to see, and I nearly bumped heads with my baby – only John being John.

When he first held her, he looked at her face and said, ‘Oh, it was you all the time.’

Our Nuclear Family

In 1969, with the fee I’d earned for my role in the film Tam Lin, I’d bought a flat in Hampstead. John had a Georgian sandstone on top of a hill in Nottingham. We trailed between the two – car packed with carrycot, pram and dogs. I slipped seamlessly into the role of being a mother. I adored my baby. Her tiny fingers, her big bright eyes, the expressions and noises she made. She brought me such joy. I cooked, I cleaned and I stitched and sewed; making her clothes, smocking her little dresses. It was the beginning of a new life for me. My career now felt secondary – somehow rather unfulfilling and dull. I only wanted to work if it didn’t take me too far from Phoebe and the hours weren’t too long. It was as if my eagerness and ambition had left; now channelled as love for my baby. I still cared for my craft, but babies and family life had become more important.

And God’s golden light continued to glow for me – bringing me work I could do on my terms. A couple of months after Phoebe’s birth I was in Pete Walker’s The Confessional with Norman Eshley and Susan Penhaligon – or Susie Penhooligan, as I call her. It was filmed in St John’s Wood, just round the corner from the flat.

It was a really bad movie, but very convenient. I took Phoebe to work in her basket.

‘How long are we going to be waiting for the lighting?’ Pete would ask while we waited for the sparks. ‘Come on, Stephanie’s tits are filling up.’ It was great; I was working and still attached to my bubba. Pete: ‘Was that the kid mewling? (sigh) Let’s go for another take.’ Pete was lovely.

John came with me to the screening. He was totally silent throughout. When it was over, he turned to Pete. ‘How much did that cost to produce?’ he asked. What else could he say? It was unspeakably bad, and I wouldn’t have missed doing it for the world.

I took to being a mother with ease, but for John, despite the fact that he was besotted with Phoebe, parenthood was a huge challenge. Ten days after she’d been born I left her with him while I popped to the shops. ‘She’s bathed, she’s changed and she’s asleep,’ I told John as I reached for my coat. ‘All you have to do is keep an eye on her.’

I got back 20 minutes later. Phoebe wasn’t in her cot. ‘John, where’s Phoebe?’ I asked, slightly bewildered.

‘Ah…’ he responded. My heart sank. Whenever John said ‘Ah…’ it was always a sign he’d done something… odd.

A trail of baby clothes – a cardigan, a babygro, a tiny hat – led to the bedroom. I followed them. Phoebe was hanging by her hands from the ladder to our platform bed. She was stark naked. Her face had turned puce.

I scooped her into my arms. ‘Phoebe’s stark naked and hanging from a ladder!’ I yelled.

‘Yes,’ he said, following me into the room, quite unperturbed by my obvious shock and horror.

‘I thought she needed her back stretched,’ he explained. ‘I read about it in the paper – it’s that baby monkey theory. If you hang a baby from a ladder they can sustain their weight. Didn’t you know?’

‘But she’s 10 days old!’

‘I thought it’d be good for her. Anyway, she looked a little hot in all those cardigans – all wrapped up like that.’

‘Hot, John? It’s January.’

That was John.

He always did these things with the best of intentions, though.

A few months after our second daughter Chloe was born in 1977, I was working on Pirandello’s The Old and the Young in Italy. She’d been quite a sickly baby since she’d been born and now she’d gone down with pneumonia. The Italian doctors had put her on a huge dose of antibiotics that weren’t working. I was phoning specialists in Rome to see if she’d been prescribed the right medication. Meanwhile, she wasn’t getting any better. Back home, John had gone missing and I didn’t know how to reach him. It was a nightmare and I was getting more and more distraught. Following the advice of the doctors in Rome, I had Chloe wrapped up in a darkened room. Finally John turned up. I didn’t know where he’d been, but suddenly he arrived in Italy. He walked in, pulled open the shutters, tore open the windows, took Chloe out of her cot and took off every stitch of her clothing. He marched out of the room and the next thing I heard was a splash – he’d jumped into the swimming pool with her.

I’d been doing what the doctors in Rome had told me. John just walked in and thought, ‘This is ridiculous.’ She got better quite quickly after that.

John did things his way.

I got home from work one afternoon and couldn’t find the dogs. It was pouring with rain. I asked, ‘Where are the dogs, John?’ Then I heard a whimpering sound, which I followed out into the garden. I found them. There they were, forlorn and rain-drenched, on the flat roof of the kitchen. John said they’d been getting under his feet.

Children came as a massive shock. Suddenly I was at the beck and call of a tiny, needy pink thing. Nature gives mothers instincts; maybe the hormones that are released into the body during pregnancy prepare you for motherhood. I fell into motherhood with enormous joy. Men are less fortunate. John had a moment of elation and then, suddenly, life was all about the pram and the paraphernalia of babyhood.

In our house in Nottingham we’d had three rooms laid out with Scalextric. It was very elaborate, with bends, bridges, chicanes, pit stops, trees and little people waving us on. I was a John Player Special – very sleek and black – and John was a red Ferrari. When Phoebe was born, I sold half of the track. I don’t think John ever forgave me. We had to get other toys and they weren’t our toys any more; they were for a baby. He had to get rid of the XK150. It was a hopeless car for a baby and two dogs.

John’s a one-off wonder, but a good and sensible husband? No. He’s a true artist – completely selfish. That’s what true artists are. They have to serve their art. They can’t help it. Any good bit of work I did, I was a less good parent.

I think if you have a baby you should make a contract with your partner which says, ‘For the first five years of this child’s life we just get on with it. We’ll look after our child and won’t even discuss whether we love each other, and we won’t break up.’ The truth is, if you break off a relationship you’ll come across the same problem in your next one because, guess what, you take yourself with you. We’d had the heady 1960s but we hadn’t got to the age of self-help books, let alone good therapy. Back then we’d only got as far as discussing Freud or Jung.

When you’re tending to and loving your baby for at least 15 hours of the day, it’s very hard to want to be tending to your husband, too. Maybe he should be tending to the two of you. Joseph is standing behind Mary, looking after Mary, who’s looking after Jesus. The man is not meant to be in competition with the baby. You only have a few. Let’s do the baby now.

Make sure your man wants to have a child, because otherwise he may not be able to be as responsible as you’d like him to be. Do we listen to what our men say? They usually tell us the truth, in actions if not words. Or do we decide on a man based on what we think we need? I’ve got friends with biological clocks ticking who have made unsuitable choices and then been amazed when their partners haven’t behaved properly. Their men told them the truth but they didn’t want to hear it. Half the time, we don’t listen to each other.

Everybody has to learn what they have to learn in his or her own way, but I think we have a huge number of questions to ask ourselves about the kind of parents we became. I’m talking about us freedom-seekers of the 1960s. We’re a very selfish generation and we’ve bred an even more selfish one, and it’s our fault. But then isn’t everything that our kids do that’s difficult our fault? It’s only the good things they do that are them. I could write a book about that.

Rather than taking away our ability to play, children rewrite the way we can play. Like nothing else, apart from acting, they give us licence to play. Children have free access to the imagination. They’re closer to the source, closer to the creative self – that is, the God-self. Half the time they’re the ones playing while we’re the ones sighing and tidying up. Have a good play with them, we can all tidy up later.

Chloe

Chloe was born in 1977. Her birth was very difficult. Two months before she was due, my membranes ruptured and I was losing amniotic fluid. I went to hospital immediately and was told labour would start within 24 hours, and that I had to stay there because I was no longer sterile and my baby was at risk of infection. I asked them at what stage of development my baby was. Her chances of survival didn’t sound good. They put me in a small ward on strict bed-rest. I lay on the bed and breathed, feeling my baby’s tiny body inside me. No longer with any fluid to act as a cushion, I could feel her skeleton – this still baby inside me was not moving. I just lay completely prone and breathed. I knew this baby had to ‘cook’ for longer. Guru Maharishi’s Transcendental Meditation came into its own. Everyone had been given a mantra. I couldn’t remember mine. I made one up. I concentrated on my breathing, and concentrated on the mantra. Slowly the amniotic fluid replaced itself. ‘Baby… Live… Baby… Live…’

Meanwhile, back home, I’d left Phoebe with John. My parents had gone to stay to help with Phoebe, but they couldn’t cope with John. They lasted a couple of days and then left. Phoebe got her head stuck in the cat flap and the fire brigade had to be called out. Then she managed to get her hands on a bottle of Calpol. She drank its contents and slept for 24 hours. I knew I had to get home.

I asked the doctor if my baby was viable. I was in hospital trying to save the life of one baby, while the welfare of my other one was at serious risk. It felt time for this baby to come out. I was induced. Chloe was born three weeks early. She’d been due on my birthday but came into the world an Aquarian. An hour after Chloe was born, as far as the hospital was concerned, I went missing. I didn’t. I’d picked up this little newborn bundle and taken us both to a bathroom that had a bath you walked down into. I filled it with water and poured in salt and iodine, and sat in it. It was very uncomfortable. My little bundle was on the side of the bath at eye level. ‘It’s just you, me and your sister now, honey,’ I told her.

It was hard for John to accept ‘the full catastrophe’ of a wife and two kids. He just wasn’t up to it; it was down to me. I was determined to get out and get home as soon as possible. The love had left the household and I had to look after my babies. I was beginning a new life which I’d brought upon myself.