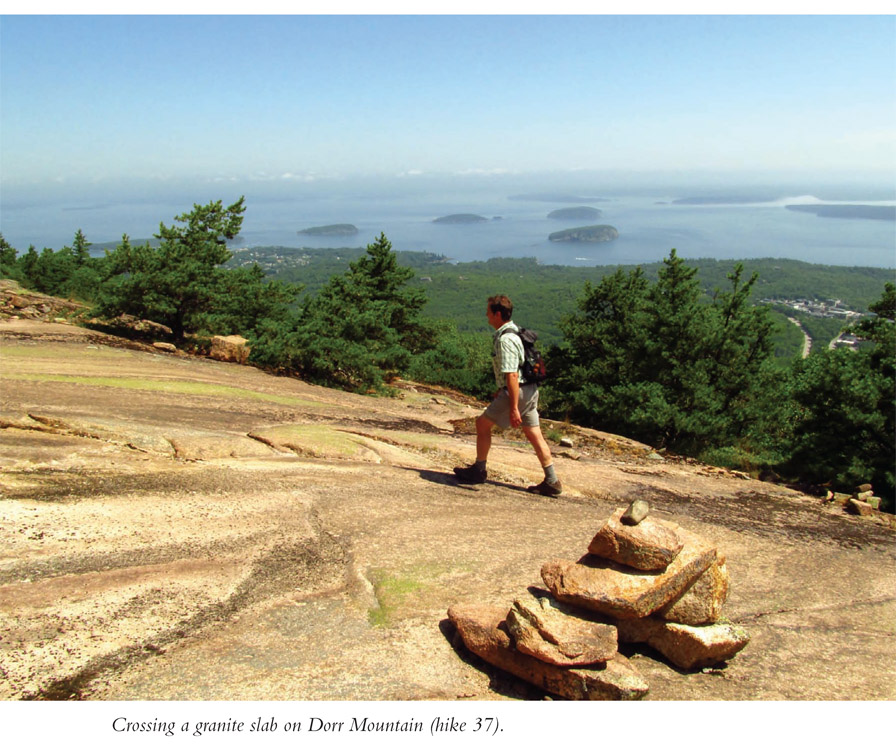

Walk an oceanside trail meandering along rocky cliffs above the Atlantic Ocean near Ogunquit, Maine. The walk starts by Ogunquit Beach and then heads south, working for a couple of blocks through the heart of touristy Ogunquit. Rejoin the coastline, savoring sweeping aquatic panoramas of the Atlantic beyond, with outcrops, coves, and small beaches in the foreground. The nearly century-old path ends where former fishing boat docks now harbor resort restaurants.

Start: Beach Street in Ogunquit

Distance: 2.8 miles out and back

Hiking time: 1.5−2 hours

Difficulty: Easy

Trail surface: Mostly asphalt

Best season: Summer for tourist watching

Other trail users: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs not allowed

Land status: City of Ogunquit, Maine property

Fees and permits: No fee for trail; parking fee almost certain

Schedule: Sunrise to sunset

Maps: Marginal Way

Trail contact: Town of Ogunquit, 23 School St., PO Box 875, Ogunquit, ME 03907; (207) 646-3032; townofogunquit.org

Finding the trailhead: From exit 19 on I-95 (Maine Turnpike) near Wells, Maine, take ME 109 east for 1.5 miles to a traffic light and US 1. Turn right onto US 1 south and follow it for 5.2 miles into the heart of Ogunquit. Make an acute left turn onto Beach Street. Follow Beach Street 0.3 mile, crossing a bridge to Ogunquit Beach and parking (fee). To pick up the Marginal Way, walk back across the bridge on Beach Street toward US 1 and pick up the gravel track leading left between two houses. Trailhead GPS: N43 14.998' / W70 35.823'

The Hike

When thinking of something as being marginal, you might conjure up something being minimal or barely making the grade. Well, the Marginal Way is anything but marginal in that context. The trail, in existence since 1925, presents spectacular far-reaching views of the Maine coastline as it arcs into the distance while delivering nearer looks to the rocks, beaches, coves, and crags that abut the Atlantic. So how did such an outstanding trail get such a name? The path curves along the edge of the Atlantic cliffs—the margin between the mainland and the chilly waters below—as the path links Ogunquit Beach to Perkins Cove.

Maine’s coastline has always been something special. Ogunquit was settled in the 1640s and became a fishing village. The name in native Abenaki language translates to “beautiful place by the sea.” And that certainly is true. However, Ogunquit’s harbor was not very good—there wasn’t one. Local fishermen tired of bringing their boats ashore nightly and took the matter into their own hands, forming the Fish Cove Harbor Association. The members dug a channel between the Atlantic and the unnavigable Josias River and then let the tide scour the passage. The anchorage became Perkins Cove, where this hike ends. Shipbuilding subsequently rose in Ogunquit, and the fishermen were a lot happier too.

Over time, visitors discovered the town’s ocean scenery. Ogunquit began evolving from a fishing and shipbuilding village to a tourist and summer cottage destination. By the early 1900s folks were already building seasonal cottages all along the southern Maine coastline, enjoying the mild summer temperatures, the ocean breezes, the beaches, and the views. Raymond Brewster became alarmed at the speed at which the natural coastline was being altered, as well as the general public losing beach access. Raised in nearby York, Maine, Brewster had moved to Ogunquit, where he became civically involved.

Brewster’s much older friend and neighbor from the York days, Josiah Chase, saw the value of the Maine coast as well. He began buying up coastline to sell to those wanting summer cottages. It was right here in Ogunquit where Chase had 20 prime acres along the elevated margin of land where the wild coastal habitat met the crashing foam of the Atlantic. It was a scenic spot, and there was a lot of money to be made by subdividing those 20 acres. Brewster petitioned Chase to instead donate his land to preserve its natural features and be enjoyed by the public in perpetuity. However, Chase had already filed a subdivision plan with the county.

Chase, who by this time was in his 80s, had served the public himself. Chase was a Union officer in the Civil War. He then practiced law and later represented York in the Maine legislature. He also directed York’s water management body. Brewster continued appealing to his friend, who, at the age of 85, eventually deeded his 20 acres to the village of Ogunquit.

▶The thirty-nine benches along the Marginal Way honor donors to the Marginal Way Preservation Fund.

Shortly thereafter, the trail that became the Marginal Way was constructed. Through the donations and easements of other property owners, the path was extended. Over the decades, the Marginal Way has been battered by storms, reconstructed, and paved with asphalt. To this day it is enjoyed by thousands of visitors every year. In order to maintain the path, a preservation fund was established in 2010. The Marginal Way Preservation Fund continues to solicit monies to maintain the Marginal Way, come what may.

The small lighthouse you see along the Marginal Way has its own story. In the 1940s Ogunquit was pumping its effluent directly into the Atlantic. The ocean waters off the town were less than clean, and beaches were closed due to health concerns. Ogunquit needed a water treatment plant, albeit a small one, to handle the town’s needs, but no one wanted an ugly pumping plant marring the scene that so many came to see. In 1948 the seaside pump was built, disguised as a little lighthouse. That is how the Marginal Way Lighthouse came to be. Disguising the water treatment pump became a model for other coastal towns. The Marginal Way Lighthouse was rebuilt in the 1990s, making the replica more in line with authentic New England lighthouses.

When you walk the Marginal Way, remember the persistence of Raymond Brewster and the generosity of Josiah Chase, because now we can enjoy some very valuable Maine coastline via the far-from-marginal Marginal Way.

Miles and Directions

| 0.0 | Start on the first gravel path leading left (south) from the west side of the bridge between the town of Ogunquit and Ogunquit Beach. Walk between a house to your left and the Marginal Way House & Motel. Soon the gravel track crosses a wooden bridge with excellent views of Ogunquit Beach and the tidal Ogunquit River. |

| 0.1 | Reach Wharf Lane. Turn right and then come to busy Shore Road. Turn left here, walking south through tourist central. |

| 0.3 | Turn left onto the balance of the Marginal Way, an asphalt track, after passing the Anchorage by the Sea resort. After you turn left onto the Marginal Way, the Sparhouse will be to your right. The narrow passage quickly reaches the Atlantic Ocean. Turn right, walking the edge above rocky cliffs to your left. Enjoy fantastic views of the coastline and beyond. |

| 0.6 | Come to a rocky outcrop to your left, near the outlet of the Ogunquit River. Walk out for stellar panoramas. Ogunquit Beach is across the river. Look north as the coastline recedes into the mist of the Atlantic. A small beach is below the outcrop. Stone steps lead to the mini-beach and a few other sandy spots betwixt the rocks. Rejoin the Marginal Way. |

| 0.7 | An asphalt spur trail leads right to Locust Grove Way. Stay straight on the Marginal Way. |

| 0.8 | Pass a spur trail leading right to Briar Bank Way. |

| 0.9 | Reach Israel Head Road and the Marginal Way Lighthouse. Keep south along the coastline. Ahead, work around a deeply cut inlet. |

| 1.1 | Pass a spur to Frazier Pasture Road. Just ahead, the trail briefly splits at a point and then comes together again. Turn into Oarweed Cove. |

| 1.2 | Cross over a bridge. Ahead, cedars shade benches overlooking the water. |

| 1.3 | Pass a second spur leading to Frazier Pasture Road. |

| 1.4 | The Marginal Way ends at a restaurant overlooking Oarweed Cove, with Perkins Cove across the way. Backtrack or turn right onto Perkins Cove Road, then right on Shore Road, then right again on Beach Street, walking past shops and restaurants galore. |

| 2.8 | Arrive back at the trailhead. |

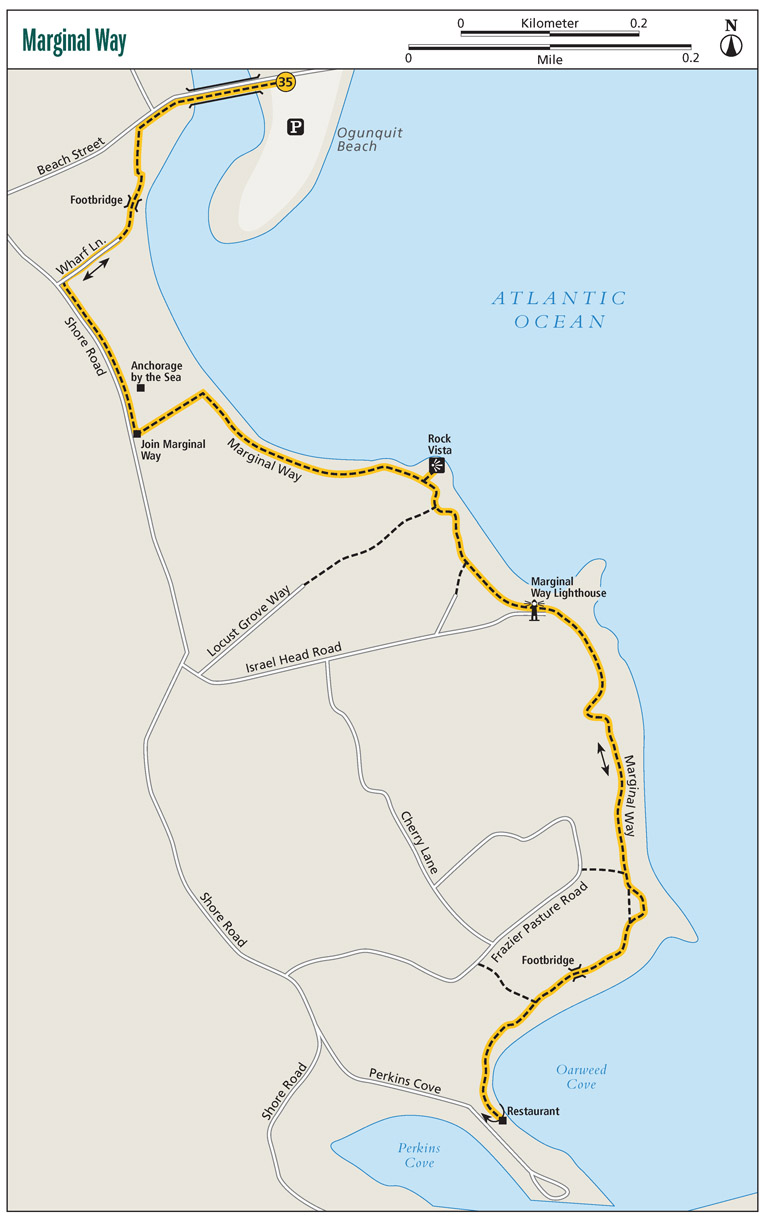

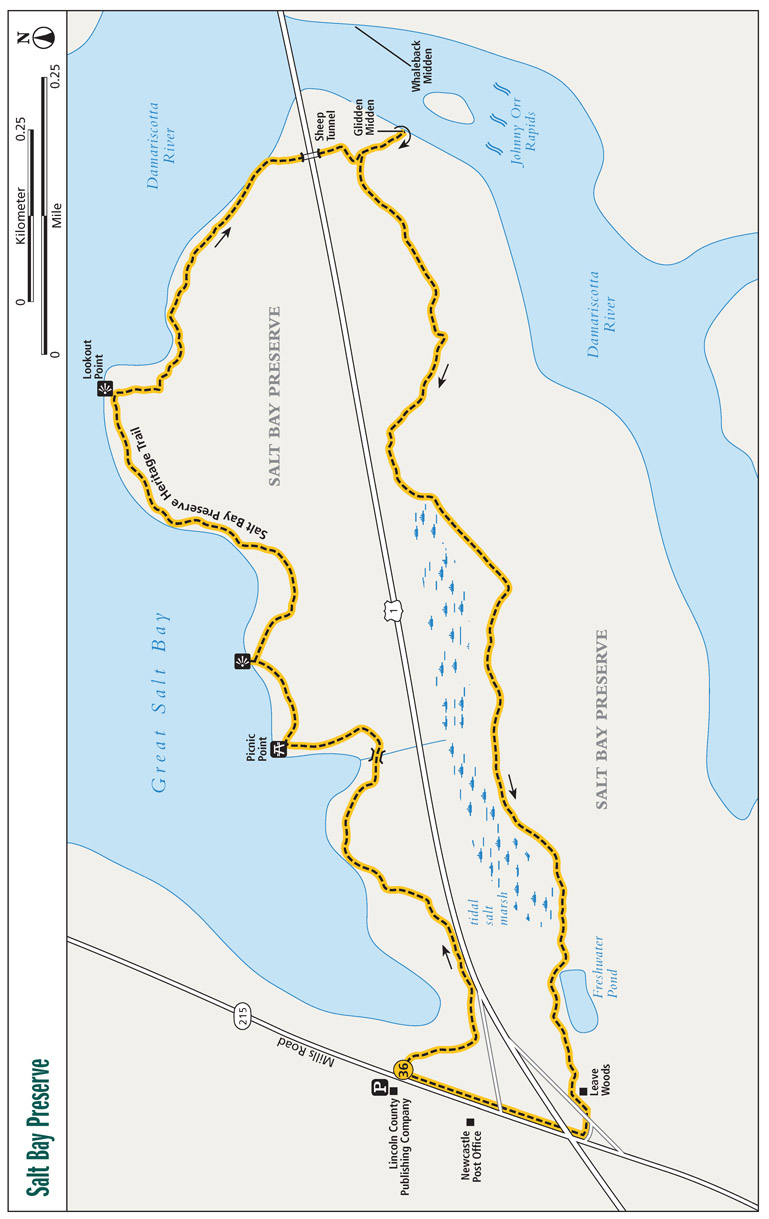

Take a walk to one of the oldest archaeological sites in Maine—the Glidden Shell Midden on the banks of the Damariscotta River. Here prehistoric tribes piled oyster shells along the shore after consuming their meats. Your hike starts along boardwalks astride Great Salt Bay. Wind through pine and hardwood forests, gaining views of the estuarine waters. View an old sheep tunnel and then reach the Glidden Midden. View the shells and complete your loop, passing a tidal marsh and a freshwater pond.

Start: Across from Loudon County Publishing on ME 215

Distance: 2.8-mile loop

Hiking time: 2−2.5 hours

Difficulty: Easy to moderate

Trail surface: Natural

Best season: Year-round

Other trail users: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs not allowed

Land status: Damariscotta River Association property

Fees and permits: No fees or permits required

Schedule: Open sunrise to sunset

Maps: Salt Bay Preserve Heritage Trail

Trail contact: Damariscotta River Association, PO Box 333, Damariscotta, ME 04543; (207) 563-1393; damariscottariver.org

Finding the trailhead: From the intersection of US 1 and ME 215 in Newcastle, Maine, take ME 215 (Mills Road) north 0.2 mile to Lincoln County Publishing Company, just north of the Newcastle post office. Trailhead parking is at Lincoln County Publishing, which they allow. However, park as far from the business building as possible, closer to the road and trailhead. The trailhead is directly across the street, on the east side of ME 215. The Lincoln County Publishing Company address is 116 Mills Rd., Newcastle, ME. Trailhead GPS: N44 2.539' / W69 31.982'

The Hike

The human history of what became Maine goes back a long time—to a period after the glaciers receded, to a time when ancient peoples settled on the shores of the shellfish-rich Damariscotta River, feasting on oysters that thrived in the warmer waters of the tidal waterway. Over time, perhaps 1,000 years, the ancient peoples piled mounds of shells on both sides of the Damariscotta. Later, European settlers found these enormous shell heaps, known to archaeologists as middens. Middens are more than just shells. They are garbage piles of sorts, containing not only shell remains but also tools, pottery, and bones of anything the ancients were using—then discarding—at the time.

On this hike we visit the Glidden Midden. Just across the Damariscotta stands the Whaleback Midden, which was once much larger than it is today. That story comes later. These two middens are the largest shell heaps on the East Coast north of Florida, and together they comprise a significant archaeological site.

Damariscotta River Association

The Damariscotta River Association is a private philanthropic organization formed in 1973. They “promote the natural, cultural, and historical heritage of the Damariscotta River and surrounding areas for the benefit of all.” The organization protects and maintains over 2,900 land acres that include 22 miles of mainland and island shoreline. You can join their group or simply make a donation. For more information visit damariscottariver.org.

There is a reason the oysters thrived here on the Damariscotta. After the glaciers receded thousands of years ago, the oceans were quite cold as they rose with the new ice melt. However, on the Damariscotta just downstream of these midden sites, the tides passed back and forth over a shallow rocky area known as the Johnny Orr Rapids—likely caused by glacial debris. These rocky shallows warmed and trapped waters of the river and Great Salt Bay, making them better suited for oysters. And the prehistoric peoples thrived along with the oyster beds, leaving a record of their presence in the form of the Whaleback and Glidden Middens.

Johnny Orr, for whom the water-warming rapids were named, settled hereabouts in the 1790s. Orr paid a high price to leave his name on these rocky shoals: His boat capsized, and he drowned floating through them. These rapids are also known as the Damariscotta Reversing Falls, since the river flows both ways due to the tides.

You will see plenty of tidal influence along this hike. After starting at the signed ME 215, bisect a small forest and then enter grassy flats on Great Salt Bay, pulsing with the flow of the Damariscotta River. Plank boardwalks lead through the flats. The Salt Bay Preserve Heritage Trail then rejoins pine-oak-evergreen forests, skirting the shore. Pass a tidal inlet to visit a pair of rocky points delivering excellent views of Great Salt Bay. Bring your lunch and dine at aptly named Picnic Point. More woodsy walking leads to Lookout Point, a narrows where the tides rush between two rocky peninsulas.

▶It is theorized that Glidden and Whaleback Middens were built up over several hundred years, starting around 2,400 years ago.

Upon reaching US 1, you will find the sheep tunnel—a metal culvert running under the highway. As its name suggests, sheep could once safely access grazing tracts on either side of this watery peninsula via this underpass. Next visit the Glidden Midden, on the National Register of Historic Places. The Glidden Midden is a waterside shell heap cut vertically by the flowing Damariscotta, making it easy to see the layers of shells marking the passage of time, much as the rings of a tree do. You can stand along the shore and see the midden rise from the water.

What is left of the Whaleback Midden is across the river and is a Maine state historic site. A 0.5-mile trail leads from the historic site parking area to the midden. The Whale-back Midden was once much larger than the Glidden Midden. However, the shell heap was seen as a valuable resource to be ground down and turned into lime. Ultimately that is what happened—the remarkable midden was literally turned into fertilizer and chicken feed! Back in 1886 the Damariscotta Shell and Fertilizer Company was formed, shipping more than 200 tons of ground shells in the first year. The Whale-back Midden was already considerably reduced. Even as the midden was mined, the excavators noted that they discovered “. . . charcoal, bones of fish and animals, and of the human frame; stone hatchets, chisels, and deep sea sinkers; bone stilettos, and tools of art and the chase; pottery, sometimes ornamented; and even lumps of clay.” What once was 15 feet high, over 1,500 feet long, and extended 400 feet back from the river was reduced to a mere “shell” of its former grandeur. The operation ceased within a few years; the business buildings burned. Think of all the lost archaeological artifacts and knowledge!

At least we still have the Glidden Midden, thanks to the Damariscotta River Association. Without them we couldn’t take this historic hike.

Miles and Directions

| 0.0 | Start from the Lincoln County Publishing Company parking lot. Cross ME 215 and join the signed Salt Bay Preserve Heritage Trail. Enter woods and quickly open into a cove of Great Salt Bay. Join a long segmented plank boardwalk spanning a grassy wetland. Come near US 1. Wild roses grow on the mainland. |

| 0.2 | Leave the boardwalk and enter oaks, pines, spruce, and balsam. Great Salt Bay extends to your left. |

| 0.5 | Cross a small tidal stream on a metal bridge. Peer into the water, looking for saltwater life such as horseshoe crabs. Reenter woods. |

| 0.6 | Reach Picnic Point. The pine-shaded locale looks north on Great Salt Bay and has a stone protrusion extending into the water. Resume the loop after your break. |

| 0.7 | Come to a second, unnamed point. This one also looks north into Great Salt Bay. Begin curving past a hill to your right as the path continues to parallel the shore. |

| 1.1 | Emerge at Lookout Point. This spot presents a good opportunity to see the tidal action of the Damariscotta River squeezing through a narrows. From here turn southeast, walking along a bluff. Look for broken shells along the trail. |

| 1.4 | Come to US 1. The metal culvert ahead of you is the sheep tunnel, once used by flocks to access grazing plots across US 1. Cross the highway and rejoin the Salt Bay Preserve Heritage Trail. Cross a wetland on a boardwalk. |

| 1.5 | Split left at an intersection and descend to the Damariscotta River and the Glidden Midden. Once at the shore, head left and come along the vertically cut mound, tide permitting. What is left of the Whaleback Midden stands across the river. Johnny Orr Rapids are downriver to your right. Backtrack and continue the loop, heading west on faded woods roads. A meadow stretches to your left. |

| 1.9 | The trail gets mushy in places as you travel between a tidal marsh to your right and seeping hillside to your left. |

| 2.1 | Come to a turn. Here a woods road you have been following keeps straight and uphill for a private home, while the trail splits right and descends. Ahead, the trail can be brushy where open to the sun. |

| 2.4 | Come along a freshwater pond to your left. |

| 2.6 | Emerge onto an on ramp for US 1. Walk left along the ramp and join ME 215, heading north. Walk under the US 1 bridge. |

| 2.8 | Arrive back at the trailhead and Lincoln County Publishing. |

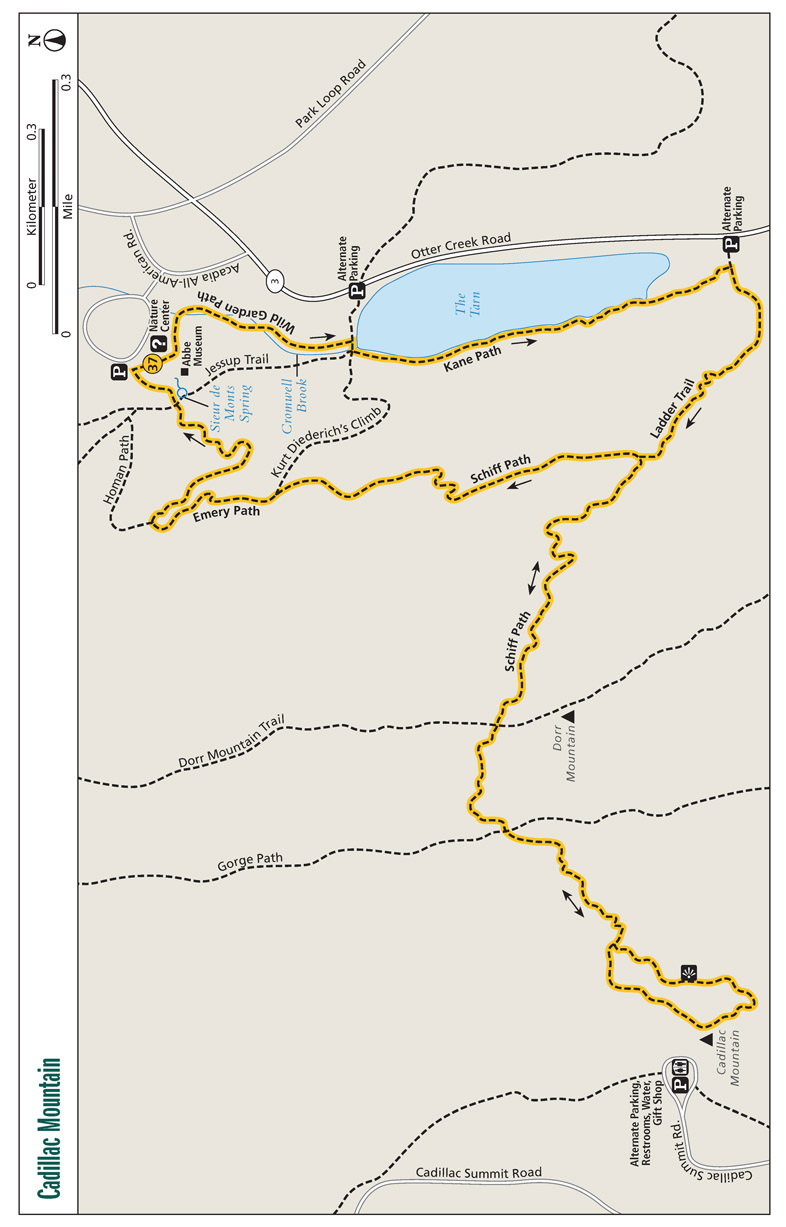

Start this view-heavy hike at historic Sieur de Monts Spring. Visit the Abbe Museum of American Antiquities, then hike century-old paths to Cadillac Mountain, Acadia National Park’s high point. En route, pass The Tarn, then climb the Ladder Trail. Surmount the open slopes of Dorr Mountain, named for the man who helped the park come to be. Make a final push for Cadillac Mountain, where vistas of the adjacent hills, Atlantic Ocean, and the isles of Maine make this a classic New England hike.

Start: Nature Center at Sieur de Monts

Distance: 4.7-mile loop with spur

Hiking time: 4−5.5 hours

Difficulty: Moderate to difficult due to elevation gains and rocky trails

Trail surface: Natural

Best season: Whenever skies are clear

Other trail users: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs allowed

Land status: National park

Fees and permits: Entrance fee required

Schedule: Park open 24 hours per day year-round

Maps: Acadia National Park

Trail contact: Acadia National Park, PO Box 177, Bar Harbor, ME 04609-0177; (207) 288-3338; nps.gov/acad/index.htm

Special considerations: Much of this hike is open to the sun—bring a hat and sunscreen. Sections are steep, involving ladders and irregular granite boulders as well as precisely laid steps. Do the hike on a clear day and be prepared to take pictures aplenty. Free bus shuttles run through the park, enabling you to hike point to point. Check the park’s website for schedules.

Finding the trailhead: From the village green in Bar Harbor, Maine, take ME 3 south toward Northeast Harbor/Seal Harbor. Drive for 2.2 miles to the Sieur de Monts entrance into Acadia National Park. Turn right on the entrance road and then quickly left into the Wild Gardens/Abbe Museum area. The hike starts at the back of the nature center. Trailhead GPS: N44 21.711' / W68 12.444'

The Hike

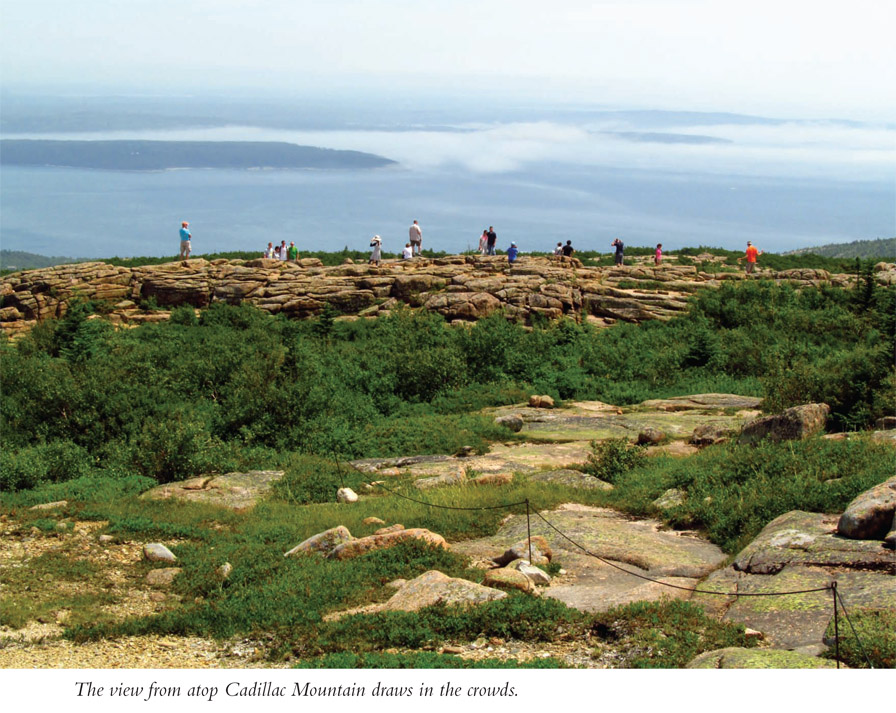

Acadia National Park proudly boasts being the first national park east of the Mississippi River. The park story took many different turns and involved many different people. The starting point is Mount Desert Island, that spectacular granite parcel just off mainland Maine, a place with a picture postcard coastline and the objective of our hike—Cadillac Mountain—at 1,530 feet the highest point on the North American Atlantic coast. You have to go south all the way to Brazil to find a peak rising higher from the Atlantic Ocean.

From the iconic summit of Cadillac, appreciate the national park level scenery—granite-topped peaks rising above an island-dotted ocean; ponds and streams adding an inland aquatic component; and more than 165 species of plants and 60 mammal species calling the park home. Also, see the villages of Mount Desert Island, where lobstermen, summer cottage owners, and tourists like us live, work, and play. Your view from atop Cadillac Mountain shows why Maine is known as “Vacationland.”

This story starts with the Wabanaki peoples. You can learn about them at the Abbe Museum, seeing artifacts from their days on Mount Desert Island. They worked Somes Sound, hunting, fishing, and gathering berries (you too can gather berries on this hike starting midsummer). Then came the French and British, battling for the coast of Maine, when Frenchman Antoine de la Mothe, Sieur de Cadillac, claimed Mount Desert Island but only left a name (thankfully only his last name). Ultimately the British kept claim to Maine, and a sailor named Abraham Somes liked that harbor on Mount Desert Island so much he moved his family here, establishing the first permanent English settlement on the island. Other harbors came to be, each supporting small fishing and shipbuilding villages.

Two artists, Frederic Church and Thomas Cole, visited Mount Desert Island, tired of painting the Adirondacks and Catskills. Their unrestrained landscapes of this truly picturesque place drew art admirers to see if the coast of Maine matched the images these painters created on their easels. Mount Desert Island was even better in person. These early visitors weren’t called tourists yet, they became known as “rusticators.” Since there wasn’t anywhere to stay on the island, local families took them in as they explored the mountains, ponds, and shoreline.

Mainers quickly saw dollars could be made by catering to the rusticators. Hotels, restaurants, and entertainment options rose around Mount Desert Island. The village of Bar Harbor came out on top, becoming a nationally recognized tourist destination. Coastal Maine’s mild summer weather sure beat the stifling cities of the pre−air conditioned Northeast.

Then came the elites of the Gilded Age. People with names like Ford, Astor, Pulitzer, Morgan, Vanderbilt, and Rockefeller built incredible summer residences they called cottages. Mount Desert Island was changed forever—or at least until the national park came. These moneyed folk saw that as natural resources (read: wood for building) were extracted and more facilities were built for tourists, especially with the advent of the automobile, the unspoiled landscape would become, well, spoiled. Summer resident and president of Harvard University, Charles Eliot, formed a public land trust to halt the despoliation. Eliot hired Charles Dorr to spearhead the effort. The mountain we climb en route to Cadillac Mountain is named for Dorr.

It took Dorr a little while to get going, but he purchased a signature feature near Bar Harbor known as “The Beehive,” a cliffy coastal headland that is popular with hikers to this day. He then obtained Cadillac Mountain. More land was acquired. Just about this time, pressure was being put on the federal government to create some national parks in the East. Dorr got national monument status for the land in 1916, and Congress created the national park in 1919. George Dorr was the first park superintendent and stayed in that position until 1943. The park wasn’t called Acadia in those early days. It went by Lafayette National Park, for the Frenchman who aided the Patriots in the American Revolution.

Name aside, the park grew with more acquisitions, especially when John D. Rockefeller donated more than 10,000 acres to the park, as well as his famous carriage roads. And about that park name . . . A family on the Schoodic Peninsula wanted to donate 2,000 mainland acres to the park but didn’t like the idea of the preserve being named for a Frenchman. Their piece of land would come only if the park’s name was changed. It took a lot of arm-twisting by George Dorr—and an act of Congress—but the additional land was secured and the park renamed Acadia.

All was well until 1947, when a dry Maine summer got worse. A fire erupted near the Bar Harbor dump, spreading over 10,000 acres of the island. It burned much of the park and also the summer homes of Bar Harbor’s elite, the millionaires who bankrolled the purchase of Acadia National Park, the first park ever to be bought entirely with private funds. Mount Desert Island was changed yet again. Hardwoods replaced conifers, and tourism for the masses replaced the exclusive playground of the elite (who are now primarily ensconced in Seal Harbor and Northeast Harbor on Mount Desert Island).

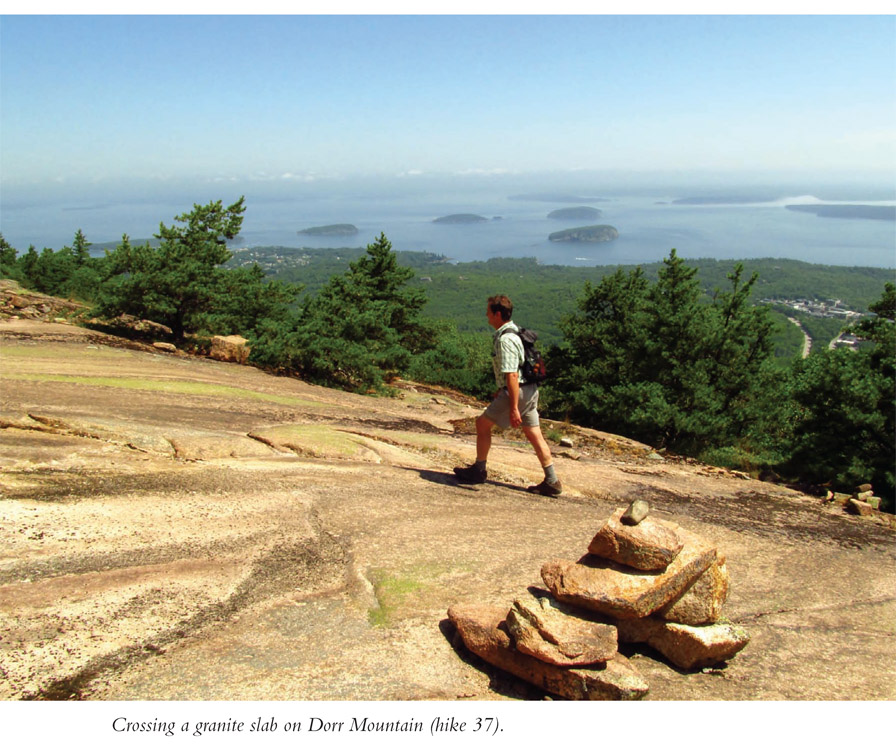

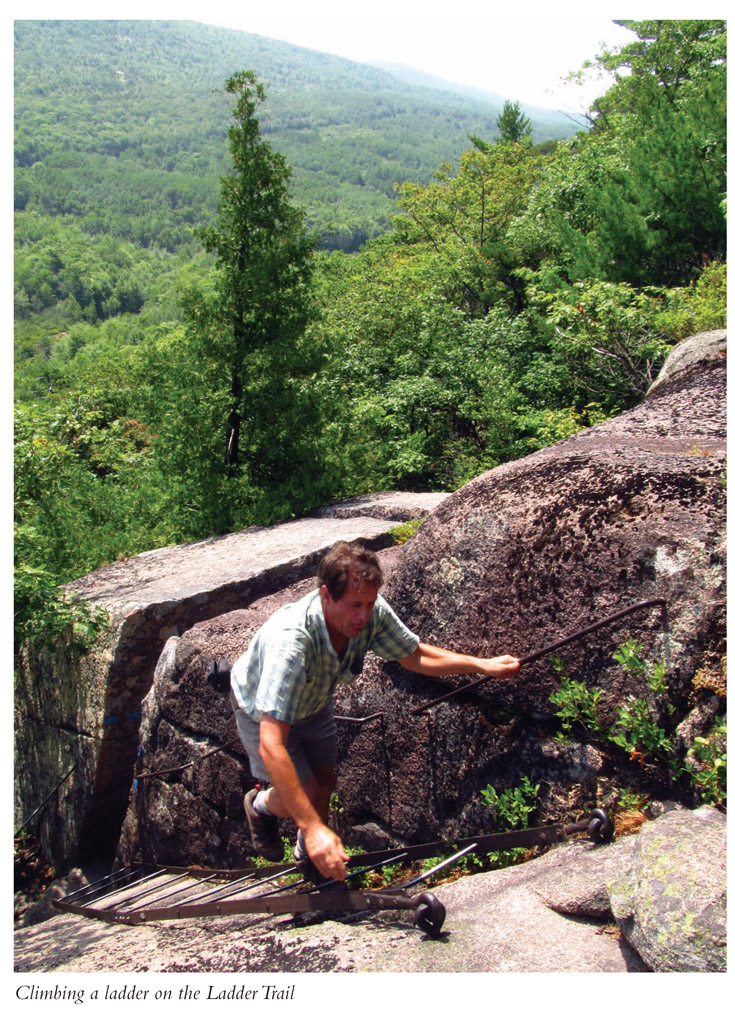

Our hike examines the legacy left by those park founders and uses trails they laid out, pathways of granite. After examining the springs, wild gardens, museum, and nature center, take off for The Tarn. Walk amid waterside boulders and then ascend the Ladder Trail, where metal ladders make the hike fun and challenging. After gaining elevation and the first of dozens of vistas, reach the crest of Dorr Mountain. Descend to a deeply wooded gorge and then climb Cadillac Mountain. Your return trip takes you past more vistas of land and sea.

Miles and Directions

| 0.0 | Start from the rear of the nature center. Walk south and join the Wild Garden Path, not the actual Wild Gardens set of interconnected pathways. Traverse a natural-surface path east through hardwoods. Come alongside Cromwell Brook. |

| 0.2 | Bridge Cromwell Brook. |

| 0.4 | Ascend granite steps to reach The Tarn. Turn right here, cross Cromwell Brook, then turn left onto the Kane Path. Walk south along the west side of The Tarn among boulders. |

| 0.8 | Turn right here on the Ladder Trail, ascending granite steps. |

| 1.0 | Reach the first of three metal ladders ascending granite slopes. Views open in exposed rock areas. |

| 1.2 | The Ladder Trail ends. Head left on the Schiff Path. Walk over open view-laden slabs between stunted pines. |

| 1.7 | Meet the Dorr Mountain Trail. It is 0.1 mile left to the peak. This hike descends a bouldery path into a rift between Dorr and Cadillac Mountains. |

| 1.9 | Reach a four-way intersection with the Gorge Path deep in evergreen woods. Keep straight here for Cadillac Mountain. Quickly emerge into open bouldery slopes. |

| 2.1 | Come to a popular outcrop used by those who drive to the top of Cadillac Mountain. Amazing panoramas open of Frenchman Bay and beyond. Continue to the mountain peak, reaching a pebble-and-concrete loop path. Restrooms, water, and a gift shop are atop the mountain. Backtrack toward Dorr Mountain. |

| 2.9 | Return to the four-way intersection and ascend the west side of Dorr Mountain. |

| 3.1 | Meet the Dorr Mountain Trail a second time. Continue backtracking. |

| 3.6 | Reach the Ladder Trail and Schiff Path. Now turn left, joining a new segment of the Schiff Path. Walk north on the east slope of Dorr Mountain. |

| 4.1 | Head left on the Emery Path. Incredible views open ahead. A side trail heads right toward The Tarn. |

| 4.3 | The Homan Path leaves left. Stay with the Emery Path, slicing between cliffs, over open slopes on a steep slope. |

| 4.7 | Pass the Jessup Trail and Sieur de Monts Spring and arrive back at the nature center. |

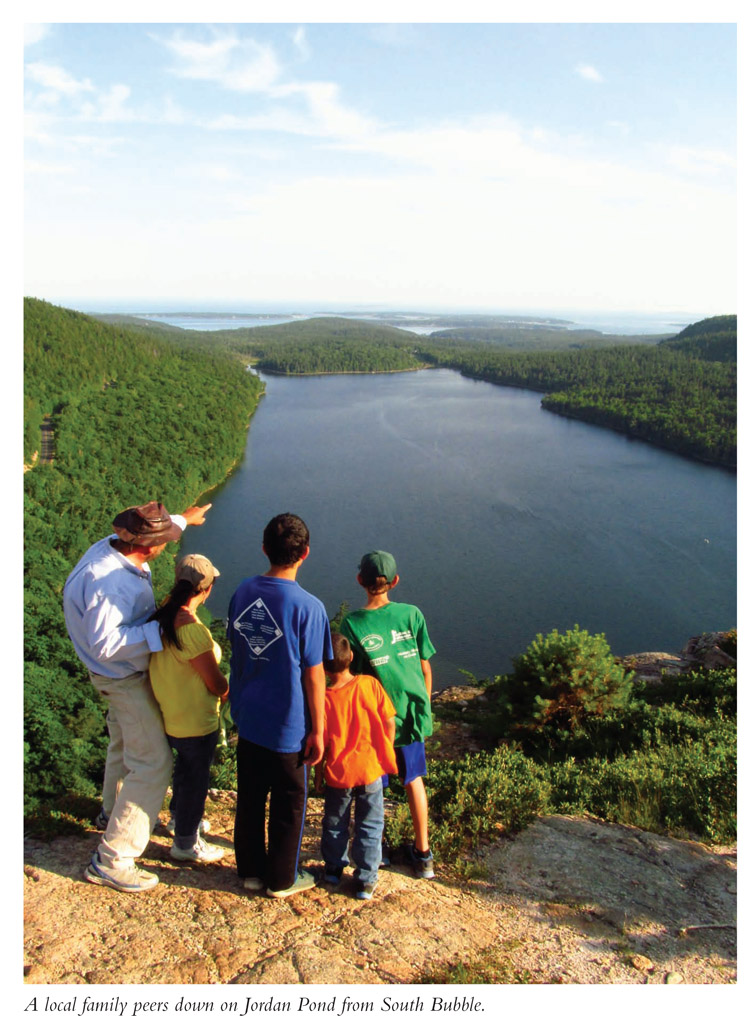

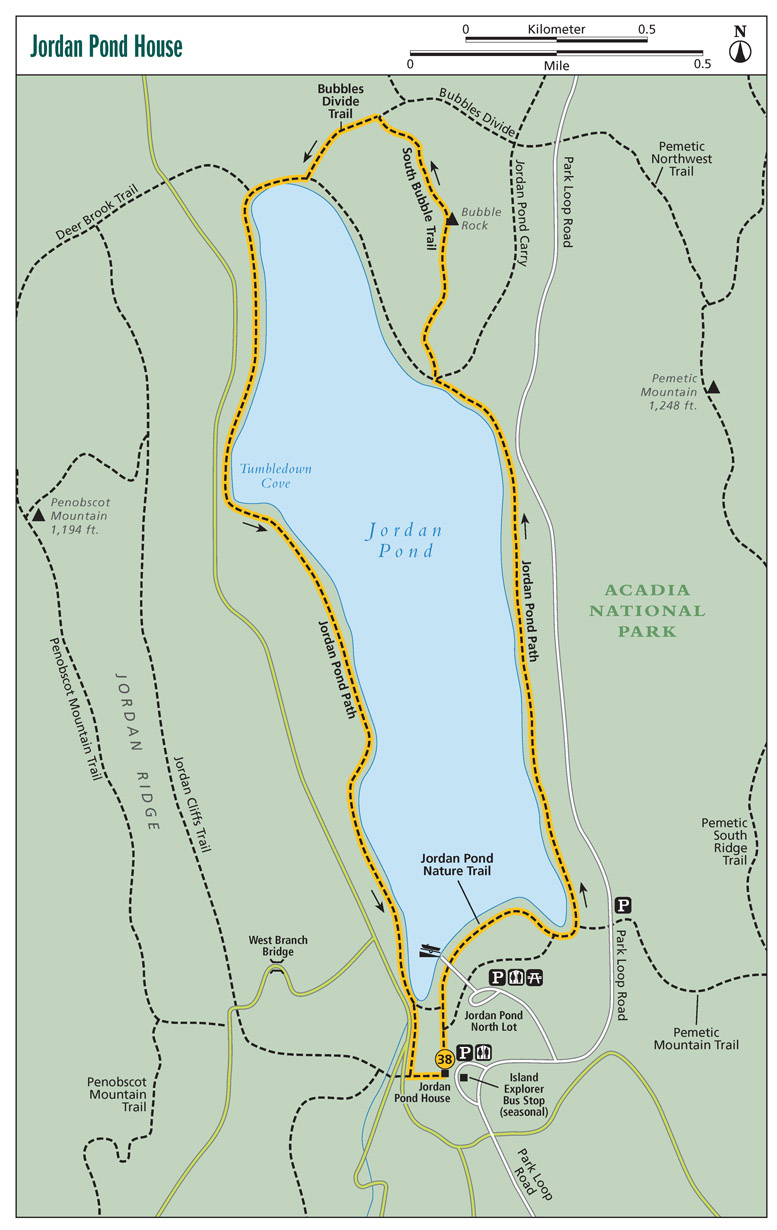

This Acadia National Park hike is long on beauty and history. Start at the Jordan Pond House, where social gatherings based on popovers and tea became legendary. From there walk around Jordan Pond, as visitors have done for more than a century. Climb South Bubble for a fantastic view of Jordan Pond and Atlantic Ocean beyond. On your return trip, walk a section of the historic carriage roads that lace the park.

Start: Jordan Pond House parking area

Distance: 4.2-mile loop

Hiking time: 2.5−3.5 hours

Difficulty: Moderate due to 480-foot climb

Trail surface: Natural, some pea gravel

Best season: Mid-May through Columbus Day for popovers

Other trail users: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs not allowed in Jordan Pond House

Land status: National park

Fees and permits: Entrance fee required

Schedule: Trails open year-round, Jordan Pond House open mid-May through Columbus Day

Maps: Acadia National Park

Trail contact: Acadia National Park, PO Box 177, Bar Harbor, ME 04609-0177; (207) 288-3338, nps.gov/acad

Finding the trailhead: From the intersection of ME 3 and the Stanley Brook entrance to Acadia National Park in Seal Harbor, Maine, take the park road from the Stanley Brook entrance north for 1.2 miles to reach Park Loop Road. Turn left onto Park Loop Road and continue for 0.5 mile to the Jordan Pond House entrance on your left. The hiking trails start at the rear of the building, near the restrooms. Trailhead GPS: N41 40.539' / W73 30.494'

The Hike

Jordan Pond lies within the boundaries of Acadia National Park, on Mount Desert Island, with national park−worthy scenery. Jordan Pond is a deep, clear tarn walled in by Penobscot and Pemetic Mountains, as well as a pair of rounded peaks known as The Bubbles. Jordan Pond is no doubt alluring. This is where George and John Jordan, from nearby Seal Harbor, built a farmhouse and sawmill back in 1847 to tap the verdant woodlands that rose all around them. Along came Melvan Tibbetts, who saw the scenic beauty of Jordan Pond and its enveloping mountains differently. After purchasing the Jordan farm in 1864, Tibbetts began renting boats for the budding Mount Desert Island tourist trade. He then saw another need and began serving food to visitors who came to boat, picnic, and hike; he even added a dining room to his place.

Tibbetts’s food idea was improved upon—some say perfected—by Mr. and Mrs. Thomas McIntire, who bought the Jordan Pond House in 1895. Mrs. McIntire began baking a hollow muffin known as a popover, serving it to guests, who loved to slather it with savory butter and preserves! A tradition was born. The island’s wealthy elite came to dine on these popovers while recreating at Jordan Pond.

The McIntires ran the Jordan Pond House for a full fifty years, establishing it as a must-visit destination for Acadia National Park visitors. It was during the last half of the McIntires’ running of the Jordan Pond House that one of Mount Desert Island’s elite part-time residents, John D. Rockefeller, bought the Jordan Pond House and its surrounding property and later donated the land as an addition to Acadia National Park.

The Jordan Pond House was eventually taken over by a park-endorsed concessionaire. Tragedy struck in 1979 when the Jordan Pond House was consumed by fire. A new structure was built, and visitors can still enjoy dining on the Tea Lawn overlooking Jordan Pond, with The Bubbles rising in the background, framed by Penobscot Mountain to the west and Pemetic Mountain to the east. The rebuilt Jordan Pond House may not have the charm of the old structure, but the setting remains spectacular.

In his nearly thirty-year involvement with Mount Desert Island and Acadia National Park, John D. Rockefeller built over 45 miles of rustic carriage roads that wind through the park. Mr. Rockefeller, a skilled horseman, wanted auto-free roads upon which he could ride. The carriage roads, now an integral part of the Acadia National Park experience, were laid out with the landscape in mind, integrating the trails into the contours of the mountains and traversing places where the scenery can be best appreciated. Large blocks of granite lining the road serve as guardrails and are affectionately known as “Rockefeller’s teeth.” Cedar signposts are installed at carriage road intersections. There are seventeen rustic stone-faced bridges, each uniquely designed with the date of construction placed somewhere on it. Each bridge is named and adds to the impressive trail system of not only the carriage roads but also the hiking trails here at Acadia National Park.

You will hike a portion of these carriage roads, constructed between 1913 and 1940, and see a couple of the bridges. First the walk leaves Jordan Pond House, where you should ignore temptation for a popover until after your hike, and joins the Jordan Pond Path. Views of the pond and the adjacent hills are immediate and inspiring. Skirt around the edge of the lake on a level path, stabilized with elaborate rockwork, especially where intermittent streambeds flow down from the lands above. The hike parallels the eastern shore then reaches South Bubble Trail. Gaze back across the pond and then take the bouldery South Bubble Trail. It is a short, steep, fun scramble up the south face of South Bubble. Open onto outcrops affording magnificent views. Look back on Jordan Pond, Jordan Pond House, Seal Harbor, and the Atlantic Ocean, dotted by the Cranberry Isles. Take a side trail to view Bubble Rock, a balanced boulder seemingly about to topple. Capture vistas of Cadillac Mountain and Eagle Lake before dropping off South Bubble back to Jordan Pond. Walk alongside a sandy beach and then turn toward Jordan Pond House, walking the pond’s edge. Open onto boulder fields as you pass through Tumbledown Cove, named for the boulders fallen from Penobscot Mountain above. Next comes a fun-to-hike extended boardwalk along the pond. Reach one of Rockefeller’s historic carriage roads and cross a rustic bridge, tracing the carriage road a short distance before making a final jaunt back to the Jordan House.

What Is a Popover?

Made with eggs, flour, and milk, popovers are baked in muffin tins in a very hot oven. Air trapped in the batter makes the inside of the popover hollow and doughy, while the outside is baked to a crispy, flaky perfection. Popovers have been served at Jordan Pond House for more than a century. They are traditionally eaten with butter and jam. The best part is that after your hike, you can eat them guilt free!

And then you can have a popover.

Miles and Directions

| 0.0 | Start from the rear of the Jordan Pond House, near the restrooms. Look for a gravel path heading right and descending toward Jordan Pond. Pass the Tea Lawn on your right. |

| 0.1 | Reach the pond and the Jordan Pond Path. Head right, counterclockwise around the pond. Soon pass a spur leading back to the Jordan Pond House. Views open of The Bubbles. Walk by the boat ramp. |

| 0.4 | Pass the last access back to the Jordan Pond area. |

| 0.5 | The Pemetic Mountain Trail leaves right. Keep straight on the Jordan Pond Path. Walk north along the scenic tarn, stepping over rock-lined intermittent drainages flowing into Jordan Pond. |

| 1.3 | Come to a trail intersection. Here the Jordan Pond Path continues along the water and Jordan Pond Carry Trail leads to Park Loop Road. You take the rocky South Bubble Trail. Begin scrambling up boulders on a marked path. Stone steps are integrated into the rock. The path steepens and becomes less wooded. |

| 1.6 | Open onto an outcrop and a view. Gaze upon Jordan Pond, the Jordan Pond House, and the Atlantic beyond. What a view! Continue up South Bubble. Ropes cordon off revegetating areas. Take the spur path leading right to Bubble Rock, also known as Balanced Rock. |

| 1.7 | Reach Bubble Rock. Views open of Cadillac Mountain, Eagle Lake, and territory northwest of Cadillac Mountain. Backtrack, pass over the crest of South Bubble, and leave the outcrop, entering a mix of forest and rock. Descend. |

| 2.0 | Come to an intersection. Turn left on the Bubbles Divide Trail. Descend an irregular boulder garden beneath thin woods. |

| 2.2 | Return to the Jordan Pond Path. Go right here on level trail, walking alongside a little beach. Bridge a stream. |

| 2.3 | The Deer Brook Trail leaves right and could be used to access a parallel carriage road. Stay left on the Jordan Pond Path. Ahead, pass through boulder fields along Tumbledown Cove. |

| 2.8 | Begin the long boardwalk running parallel to the shore. |

| 3.4 | Leave the boardwalk and join a gravel track. |

| 3.7 | Reach the southwest corner of the lake and emerge onto a carriage road. Cross the stone bridge here and turn right on the carriage road. |

| 3.8 | Come to a major intersection. Most paths go right over a bridge, but you take a left, uphill, on a singletrack trail. |

| 4.2 | Arrive back at the rear of the Jordan Pond House. |

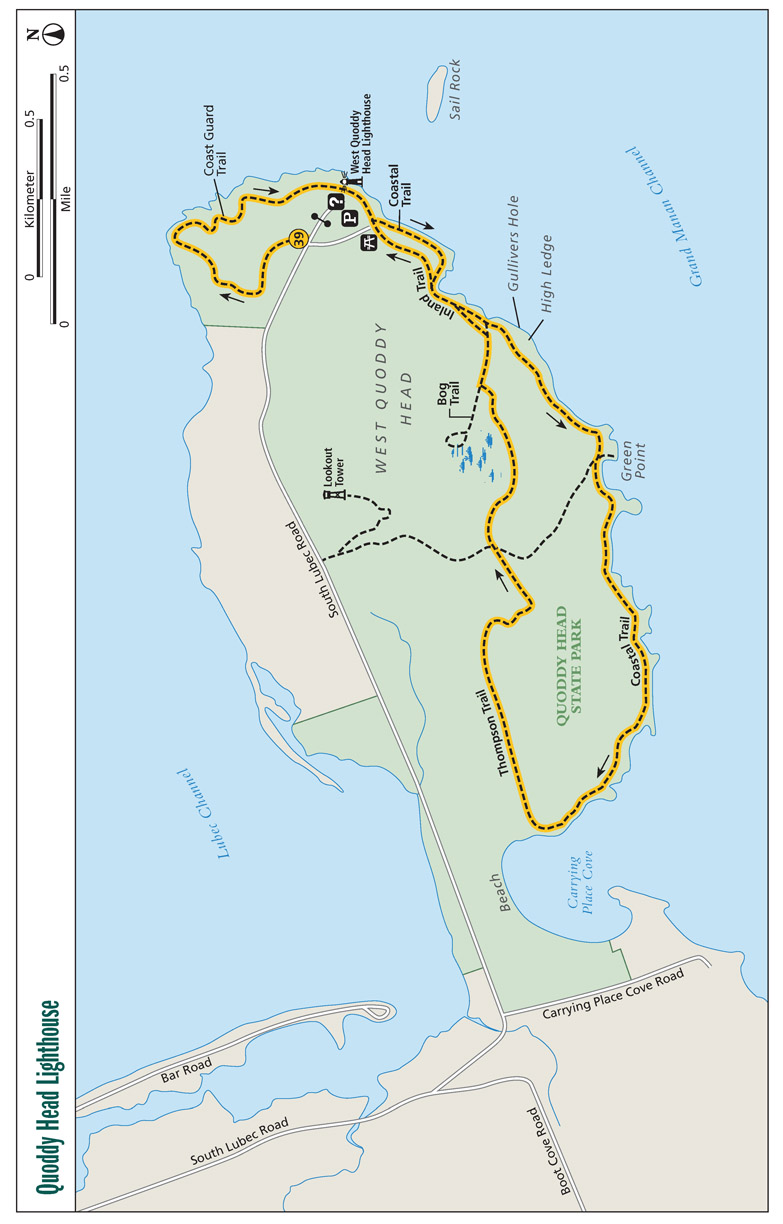

This is one ultra-scenic hike. Start at the easternmost point in the entire United States, then curve along the rugged Maine coast to reach historic West Quoddy Head Lighthouse, its current incarnation in operation since 1857. Continue walking along cliffs above the Atlantic, viewing crashing waves in the near, with island and big water panoramas in the far. Return to the trailhead via deep woods inland paths.

Start: West Quoddy Head Lighthouse parking area

Distance: 4.4-mile loop

Hiking time: 3−3.5 hours

Difficulty: Moderate

Trail surface: Gravel and natural

Best season: Summer to access visitor center

Other trail users: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs allowed

Land status: Maine state park

Fees and permits: Parking fee required

Schedule: Open sunrise to sunset

Maps: Quoddy Head State Park

Trail contact: Quoddy Head State Park, 973 South Lubec Rd., Lubec, ME 04652; (207) 733-0911 (Apr−Oct); (207) 941-4014 (Nov− Mar); maine.gov

Finding the trailhead: From ME 189 in downtown Lubec, Maine, turn right onto South Lubec Road and continue 2 miles to a fork. Bear left and continue 2 miles to the park entrance. Trail-head GPS: N44 48.966' / W66 57.158'

The Hike

This part of Downeast Maine is also known as the Bold Coast, where high cliffs and rock shores give way to sporadic cobble beaches facing the crashing Atlantic Ocean head on, where slow but sure weathering has carved a landscape that is inspiration for painters and photographers alike. Then there’s West Quoddy Head Lighthouse, the historic red-and-white-striped beacon with its caretaker’s house complementing the natural splendor. Finally, add the distinction of using the easternmost trail system in the United States at the easternmost point in the entire nation!

This hike of superlatives will deliver exceptional scenery, even if the area is blanketed by one of the fogs for which it is famous. The mist will add an air of otherworldliness to the trek. But first, let’s go back in time to 1800, twenty years before Maine was admitted to the Union, to when mariners operating out of nearby ports petitioned the US government to put a lighthouse hereabouts, assisting passage through these waters. In 1808 the first beacon at Quoddy Head was lit, and lighthouse keeper Thomas Dexter began earning his $250 annual salary.

Yet the original octagonal wooden structure was headed for darker times. During the War of 1812, nearby Eastport was occupied by the British. They also commandeered the lighthouse, giving it the dubious distinction of being the only lighthouse in Maine to be foreign-occupied, albeit for a brief period. We Americans have a penchant for making things bigger and better; thus, in 1830 a second lighthouse was built here. The white, circular structure of stone was an improvement over the wooden original.

However, that wasn’t good enough. In 1857 the circular brick structure you see today was constructed. (These three increasingly strong towers recall the childhood story of “The Three Little Pigs.”) This newest model cost $15,000. The structure was not only sturdier but also had a Fresnel lens—a magnifying complex of mirrors that vastly improved the distance from which the light could be seen. That same lens is still in use today.

How Many Stripes?

The painting of lighthouses, despite their colorful anointings, is not a matter of whimsy. Lighthouses are painted different from one another so that mariners can differentiate one light from another on sight, helping them figure out their position. The West Quoddy Head Lighthouse is easily distinguished by its red-and-white horizontal stripe pattern. However, the number of stripes has changed during the lighthouse’s numerous paint jobs these past eight generations. There have been as few as six red stripes and as many as eight alternating with the white stripes. Go figure.

A lighthouse keeper’s employ was a unique sort of job and life, the type of job Hollywood would have a reality show about today if lighthouses weren’t automated. That first light keeper, Thomas Dexter, was a Revolutionary War veteran who “hauled oil, lit lamps, rang foghorn bells and endured bad weather.” His house doesn’t remain. The keeper’s house currently on-site was also built in 1857 and now serves as the lighthouse visitor center. Inside, there is all sort of fascinating information about life here at the easternmost tip of the United States. Originally built for one family, the house was added onto in 1899 and then divided into a duplex, whereby the lighthouse keeper and the assistant lighthouse keeper—and their families—could reside here at Quoddy Head. The structure was returned to a one-family dwelling in the 1950s. The last light keeper lived here until 1988, when the light became automated.

The lighthouse is still an important beacon, helping boaters navigate the island-and-rock-studded Bay of Fundy, also known for its enormous tides and the biggest whirlpool in the Western Hemisphere. Nevertheless, this part of the Atlantic Coast is best recognized for its fog. An important function of the West Quoddy Head Lighthouse was to sound out during fogs. This process also underwent an evolution much as the lighthouse itself did. Cannons, bells, triangular bars, even compact air trumpets were used, all with limited effect. Even at that, the soundings did decrease shipwrecks. As time went on, steam-powered whistles were used. Things changed by 1900, when the first incarnation of the foghorn was invented. Its deep sounds carried well in the mist. In the 1930s the foghorn was fully developed and remains in use today.

Don’t be surprised if your hike here is in the fog. If so, the coast will have an ethereal effect. However, clear days will deliver stunning views of Canada’s Grand Manan Island, among other coastal features. Fog or sun, the immediate shore will make you want to stop and snap shot after shot. The trek starts on the Coast Guard Trail, where it heads north and stops by a vista point on an elevated wooded deck. You can see across to big Campobello Island and the balance of Passamaquoddy Bay. Turn back along the coast and reach the West Quoddy Head Lighthouse, very near your starting point. Stop in the visitor center and appreciate this brick beauty as it shines for passing mariners. From there, head south along the coastline, passing the park picnic area and an accessible cobblestone beach. Ahead, visit places like Gullivers Hole and High Ledge. Look for freshwater cascades spilling from the cliffs below. Green Point and other outcrops will beckon you. The trail turns into quiet Carrying Place Cove, where Indians portaged the peninsula to avoid the swift tides and dangerous whirlpools of the Bay of Fundy. The hike then enters inland forest on the Thompson Trail, where you travel under rich, mossy, evergreen maritime forests. Take the optional spur to an arctic bog and grab one more look at the lighthouse before ending the scenic walk.

Miles and Directions

| 0.0 | Start on the Coast Guard Trail, a gravel path heading north from the parking area and away from the lighthouse. Enter rich evergreen woods of spruce and fir, below which spreads spongy moss. |

| 0.4 | Reach an observation bench looking north toward Canada. A wooden observation deck is reached by forty-four steps. From this perch, the view widens to the east. After leaving the observation deck, resume the Coast Guard Trail, now a primitive, rooty, rocky track. Keep along the coastline. Great views lie ahead. Occasional spurs head to vistas. |

| 0.8 | Emerge at the West Quoddy Head Lighthouse, with its additional outbuildings. Enter the visitor center to absorb in-depth local history. From there walk south along the coast and pick up the signed trail indicating “To Beach.” |

| 1.0 | Come to the park picnic area. Keep straight on the Coastal Trail and soon pass wooden steps leading down to a cobblestone beach. |

| 1.2 | Reach an intersection. Stay left here; the path leading acutely right heads back to the picnic area. |

| 1.3 | The trail splits again. Stay left as the trail heading right, the Inland Trail, goes toward the bog. (This is your return route.) Ahead, a shortcut leads right to the Inland Trail. Pass by steep cliffs and Gullivers Hole, an eroded, nearly enclosed cliff. |

| 1.7 | A short spur leads left to Green Point. Continue working along the coast through woods and brush, over undulating terrain. The views continue to amaze. Use occasional bridges, wooden steps, and boardwalks to make your way among dramatic headlands. |

| 2.7 | Meet the Thompson Trail after turning into Carrying Place Cove. Turn right onto the Thompson Trail as a user-created path keeps straight. Head inland on a slight uphill. |

| 3.8 | Reach the Bog Trail. (Option: To explore it, leave left and circle through an arctic bog.) To continue, stay right, now on a gravel path. |

| 3.9 | Pass a shortcut leading right to the Coastal Trail. |

| 4.0 | Meet the Coastal Trail. Keep straight. |

| 4.1 | Take the Inland Trail spur leading left to the picnic area. |

| 4.2 | Emerge at the picnic area. Rejoin the Coastal Trail, returning to the West Quoddy Head Lighthouse. |

| 4.4 | From the lighthouse, take the short, gated road back to the trailhead. |

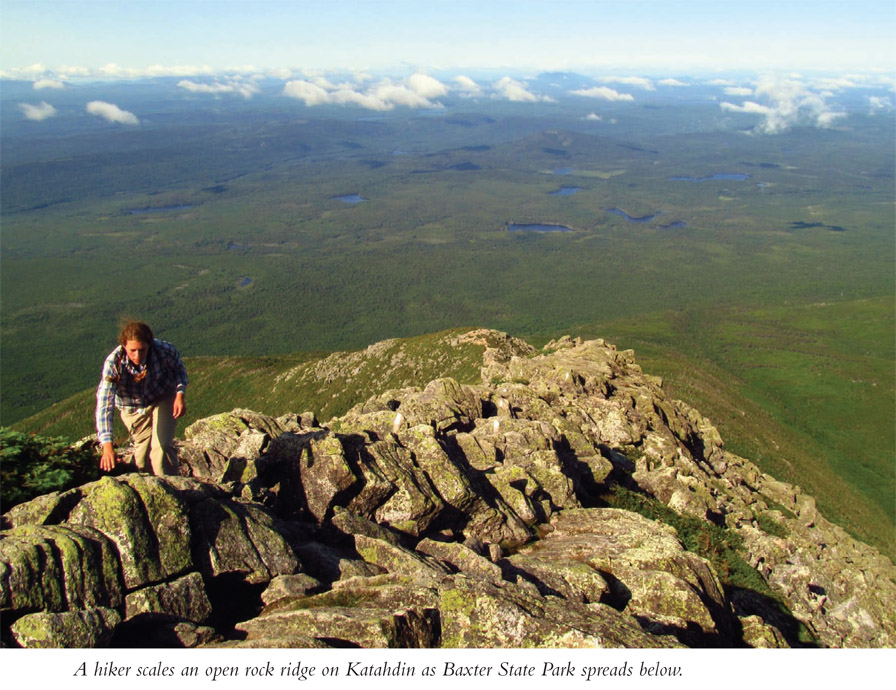

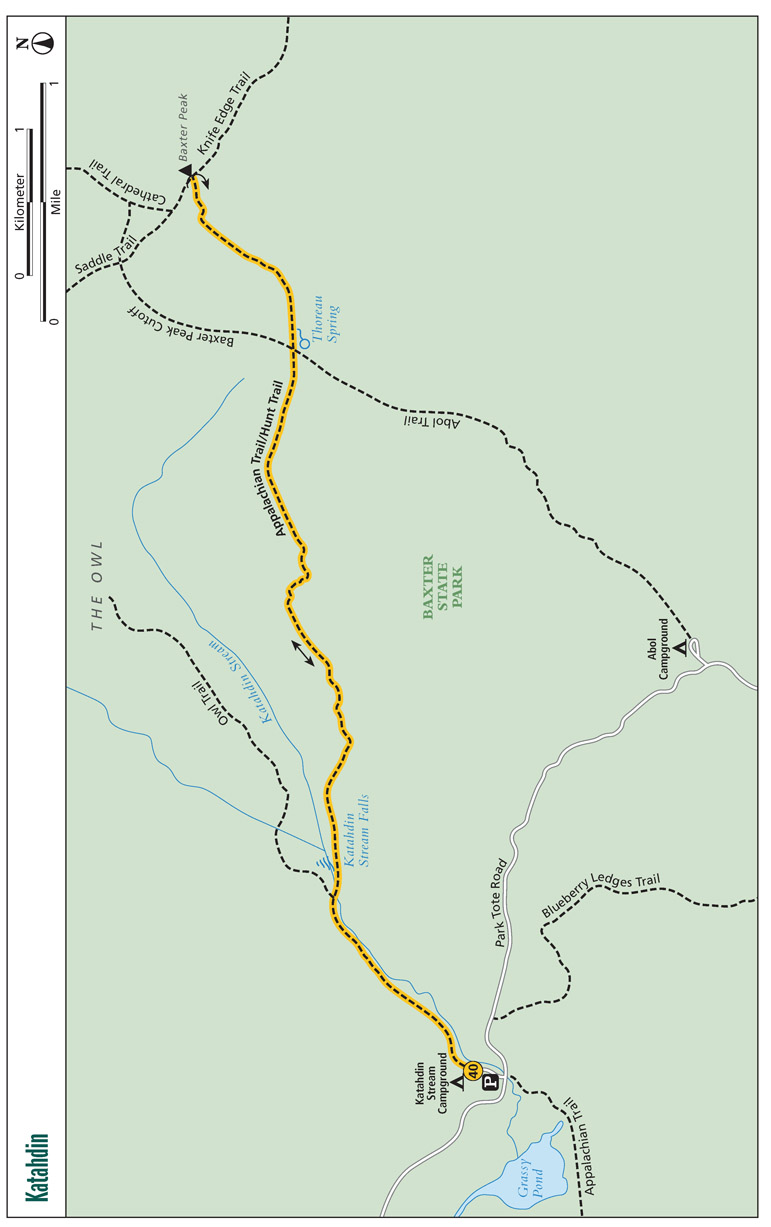

This is the most difficult hike in this guide, to arguably the most significant peak in all of New England. Katahdin is the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail and is a good place to contemplate the historic nature of the AT. The route to the peak uses a long-traveled path within the confines of equally historic and wild Baxter State Park.

Start: Katahdin Stream Campground

Distance: 9.6 miles out and back

Hiking time: 8−11 hours

Difficulty: Very difficult due to 4,188-foot climb

Trail surface: Natural

Best season: Summer for long hours of daylight for hiking

Other trail users: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs not allowed in Baxter State Park

Land status: Maine state park

Fees and permits: Park entrance fee required

Schedule: Park open 6 a.m. to sunset during the warm season

Maps: Baxter State Park, Abol Trailhead map

Trail contact: Baxter State Park, 64 Balsam Dr., Millinocket, ME 04462; (207) 723-5140; http://baxterstateparkauthority.com

Finding the trailhead: From exit 244 on I-95 near Medway, Maine, take ME 157 west through Medway, East Millinocket, and Millinocket. Proceed through both traffic lights in Millinocket. Bear right at the three-way intersection after the second traffic light in downtown Millinocket. Bear left at the next Y intersection, staying on the main road. (ME 157 ends in Millinocket; the road to the park is unnumbered and has many names—Baxter State Park Road, Lake Road, and Millinocket Lake Road.) Eight miles from Millinocket, pass buildings and the Northwoods Trading Post on the right. Continue another 8 miles on the blacktop road to Togue Pond Gatehouse. All the major turns are signed for Baxter State Park. Trailhead GPS: N45 53.240' / W68 59.993'

The Hike

You just never know where a hike may lead you. In the case of Percival Baxter, hiking, fishing, and camping in the Maine woods led the one-time Maine governor to purchase lands for and create Baxter State Park, the entity that encompasses Mount Katahdin—Maine’s highest peak at 5,268 feet, as well as the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail. And it is to the top of Mount Katahdin where this hike leads us. After all, Baxter’s idea was to create a park “for those who love nature and are willing to walk and make an effort to get close to nature.”

Baxter’s foresightedness inspired. And it was at that same time and in the same vein that the Appalachian Trail was conceived and routed end to end. However, let’s start with the year 1930. Baxter’s three-year term as governor had ended six years prior. In 1930 he made his initial purchase of 6,000 acres, acreage that included Mount Katahdin. The next year he donated the land to the State of Maine. And so it went—purchase land, give it to Maine, purchase land, give it to Maine—for a stunning thirty-two years!

But that wasn’t all. Baxter had a specific vision for this state park. To execute his directives, which included having wilderness, logging, and hunting areas, the land needed to be managed. And that cost money. To that end, Percival Baxter left $7 million in a trust to endow the park with operating funds, rather than burdening the taxpayers of Maine. To this day, nary a dime comes from the state. Monies to staff and operate the park originate from the endowment, timber sales, and fees paid by park users.

Baxter State Park comprises a whopping 209,644 acres, one of the largest state parks in the nation. It contains not only the Katahdin massif but also rolling lower elevation forests, streams, ponds, wetlands, and trails galore to explore in this year-round home to moose, black bear, deer, and lesser mammals. The richness of life moves down the chain, even to annoying bugs such as mosquitoes and blackflies. Flora ranges from the unique and fragile alpine tundra atop Katahdin down to the hardwood and evergreen forests carpeting the lower reaches.

The massif held sway with aboriginal Mainers. The Penobscot Indians dubbed it Katahdin, which means “greatest mountain.” However, in 1931 the US Geological Survey named the actual high point, the summit, the tiptop, Baxter Peak—a nod to Percival Baxter. So don’t let that confuse you. Besides, almost everyone refers to climbing Katahdin rather than Baxter Peak.

In the twentieth century, Mount Katahdin’s fame spread nationwide. It started with Benton MacKaye conceiving the idea for an “Appalachian Trail” extending the entirety of the eastern mountains, a destination to which man could break off from the grind of modern life. The first mile of the Appalachian Trail was laid out in 1922, and by 1937 the first end-to-end route was completed.

▶Charles Turner made the first recorded ascent of Katahdin in 1804.

Katahdin’s place in AT lore came to be when another proud Mainer named Myron Avery, who happened to be the chairman of the Appalachian Trail Conference, put forth the idea of making Mount Katahdin the trail’s northern terminus. It was made so. And today, among AT enthusiasts, the name Katahdin is spoken with a reverence unlike any other peak on the trail.

Traditionally, the Appalachian Trail has been thru-hiked from south to north—from Springer Mountain, Georgia, to Mount Katahdin, Maine. Thru-hikers normally begin in spring, ending up in the shadow of Katahdin anywhere from four to six months later. You may see some thru-hikers in late summer/early fall, making that final ascent. Even after covering roughly 2,180 miles (the exact mileage continually changes due to trail reroutes), they still have 4.8 miles and 4,188 feet to climb. Once they get to the top, they have to get back down.

The Glory of Katahdin

Percival Baxter realized the revitalizing qualities of time spent in nature and that Mount Katahdin was one of those special places. Being a Mainer, the peak was dear to his heart. When Baxter gave the mountain away, he penned the following words. They are inscribed on a plaque embedded into granite at the base of the mountain, where this hike starts.

Man is born to die,

His works are short-lived.

Buildings crumble,

Monuments decay,

Wealth vanishes.

But Katahdin in all its glory,

Forever shall remain

The Mountain

Of the People of Maine.

This route to Katahdin follows the AT/Hunt Trail, leaving Katahdin Stream Campground. You will follow Katahdin Stream, crossing it just before arriving at Katahdin Stream Falls, a crashing 60-foot cataract. The ascent sharpens and you begin working up boulders. The route later joins an all-rock ridge, where you are working over boulders most of the time. The going is extremely slow. Pass through the Gateway, the upper part of the boulder ridge, before opening onto the aptly named Tablelands, an above−tree line windswept plain of rock and fragile alpine plants. Pass Thoreau Spring, named for the renowned New England naturalist who climbed Katahdin in 1846. The AT winds upward through continual rock gardens, topping out on Baxter Peak, marked with an oft-photographed sign. It is well worth the challenges to scale Katahdin.

Here is some important advice: Start early, very early. It usually takes longer to get down than up, due to fatigue, the trail’s steepness, and irregular terrain. Be prepared for weather extremities of wind, temperature, and precipitation atop the mountain. The hike requires using all fours, and at times it is more bouldering than hiking. This is a hike not be taken lightly. That being said, thousands of trekkers do it every year. Be prepared.

Miles and Directions

| 0.0 | Start on the Appalachian Trail/Hunt Trail at the upper end of the day-use parking area at Katahdin Stream Campground. Walk through the upper campsites, with Katahdin Stream to your right. Pass campsite #16, then pick up a bona fide hiking path. Sign the trail register. |

| 1.0 | The Owl Trail leaves left. Stay straight with the AT/Hunt Trail. Ahead, bridge Katahdin Stream. There is a restroom after the crossing. |

| 1.2 | Reach Katahdin Stream Falls. A spur trail leads left to the crashing stair-step froth of whitewater. Continue up, clambering over stone steps among low shrubs. The trail steepens. |

| 1.9 | Cross a streamlet. This is a good place to rest before the climb ahead. |

| 2.2 | Pass an overhanging boulder to your left. Big boulders become more common. |

| 2.6 | Emerge onto an open boulder field among stunted trees. Views open of the lands below. Begin the prolonged boulder ascent, at times using metal rungs hammered into rock. Take your time, and make every move count. |

| 3.3 | Emerge onto the Tablelands after passing through the Gateway, the final maze of boulders. You are above tree line. Follow the blazes across a surprisingly level plain of rocks and fragile alpine flora. Stay on the trail. |

| 3.8 | Reach a four-way trail intersection at signed Thoreau Spring. Keep straight on the AT/Hunt Trail. A moderate but steady ascent soon resumes. The ridgeline narrows. Expect strong winds. |

| 4.8 | Reach Baxter Peak, the apex of Mount Katahdin, marked by a sign. Other trails spur from here. Backtrack, giving yourself more time to make it down than up as you descend the boulder fields. |

| 9.6 | Arrive back at the trailhead. |