ONE EVE NING AFTER A LONG DAY’S shearing, Domingo and I and a gang of high sierra shepherds were sitting in Ernesto’s Bar in the woods below Pampaneira, eating tapas of meat from the grill – carne a la brasa – and doing some earnest costa tasting. The conversation had turned to how much we all loved our ganado: our flocks. Odd though it may seem, this is a fairly popular topic of conversation hereabouts.

As the shepherds droned eloquently on about their feelings for their charges, I noticed Ernesto’s son watching me. He was fairly well gone and seemed to be plucking up the courage to ask me a question. Finally on his way back from the bar he lurched towards me and whispered breathily in my ear, ‘Do you too love the ganado?’ ‘I cannot deny it but I do,’ I whispered in reply, and we smiled bashfully at one another.

Domingo caught the undertone. ‘What do you mean?’ he interrupted. ‘You don’t even know your own sheep. When did you last walk with them? You’ve been putting up fences to do your job for you. Those sheep of yours wouldn’t even follow you if you wanted them to. That’s not loving the ganado.’

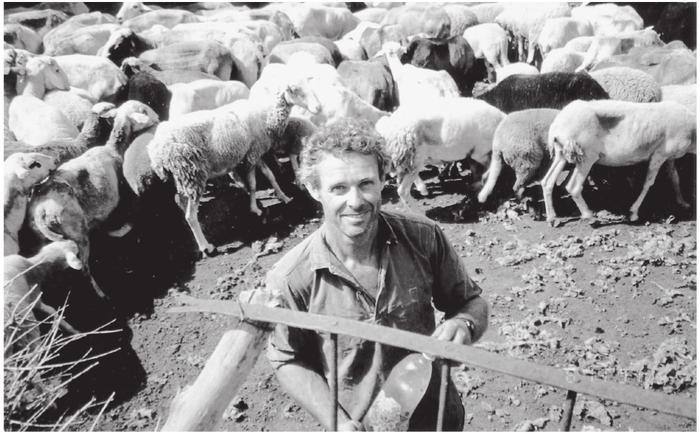

These were wounding words, but I couldn’t deny that there was a certain truth in them. Since the fiasco of the lost flock I had been busy erecting fences over a large swathe of the secano precisely so that I could shrug off the more wearisome duties of the shepherd and get on with more pressing jobs on the farm. Also neither I nor the sheep had quite mastered the easy technique of the Alpujarran shepherd who strides at the head of a flock, whistling for the sheep to follow. Instead I would be left bringing up the rear, shouting and pitching stones. It wasn’t the most flattering comparison. My sheep were in good condition, well kept and produced a good number of lambs, but then no one was criticising my sheep. I shrank back under these mortifying reflections and waited for Domingo’s show of pique to pass and for the conversation to turn to other matters.

Soon enough the tender eulogising of sheep had shifted into an angry tirade against the dealers. Everyone, it seemed, had fared badly at the last round of selling and all were swearing to hold out for a better price next time.

‘I don’t see why we should bother with the dealers at all,’ I piped up. ‘We can’t do worse than we’re doing now if we cut out the middle man and sell our lambs ourselves.’ It was a bold outburst in such company but I rather enjoyed the lull it created in the conversation. ‘When the dealers get a knockdown price they take the lambs to Baza to turn over a quick profit,’ I continued recklessly, ‘so why shouldn’t we try our luck selling direct? I know I’m going to give it a go.’ A few seconds before I hadn’t known anything of the sort but the looks of startled interest on the faces around me had transformed the vague idea that had been hovering at the back of my mind into a one-man mission. It felt good to be back in the role of innovator again.

Baza market is the largest livestock market in Andalucía, set on a high plateau about three hours’ drive away in the north of the province. The dealers who frequent it are a hard-bitten crowd and trying to offload lambs direct would be tricky and contentious even without the handicap of being a foreigner and a relative novice to the trade. But I couldn’t back out now.

‘The dealers won’t like it a bit,’ announced one of the shepherds, his eyes glinting with excitement at the thought. ‘No,’ said another, ‘but it’s something that’s got to come, they can’t go on screwing us for ever.’

‘Well, the dealers can look after themselves,’ I replied. ‘I’ve got forty good lambs that are ready to go. Does anyone want to come with me?’

Perhaps I hadn’t phrased the question clearly enough because the debate raged on in abstract terms without anyone actually answering it. Domingo’s voice, however, eventually cut through the bluster. ‘I’ll come with you,’ he said. ‘You have a word with Baltasar about his trailer. We can give it a try at the market a week tomorrow.’

Baltasar, one of my sheep-shearing cronies, has a powerful four-wheel-drive truck and a livestock trailer. He agreed to take us to Baza Market because he needed to stock up on hay-racks and things for his flock. So, on a sharp winter’s evening, we loaded the lambs into the trailer and, as a counterweight, stuffed the car with various people who had decided to come along for the ride. Baltasar drove; then there was Domingo and his cousin Kiki, a lad I’d not met before, for the good reason that he was just out of jail for an episode involving a sawn-off shotgun and a discotheque; and lastly Baltasar’s father, Manuel. Naturally I was stumping up for the expedition.

We set off in a leisurely fashion at about nine o’clock in order to get to the market at midnight. This was some unfathomable notion of Domingo’s. The market started at six in the morning but Domingo reckoned it was best to get there before the rush started; midnight seemed a bit excessive to everybody else but Domingo was adamant. In the event, as ever, it took a while to get away. As we passed through Órgiva we were flagged down for a chat by every passer-by who happened to know Domingo or Baltasar, or anyone who was simply curious about the trailerload of lambs. By the time we finally left the town it seemed that all its inhabitants knew of my madcap plan to sidestep the local dealers and sell the lambs direct at Baza market.

The same thing happened in Lanjarón, Baltasar’s home town, but at last we were away, leaving the mountain roads of the Alpujarra and grumbling slowly up the long hills that lead to Granada. The cool evening had become a freezing night, so the heater was on and the car was full of soporific fug. Soon everyone was asleep except Baltasar, Manuel and me. Baltasar was awake because he was driving, Manuel was awake because he was holding forth in an unbroken narrative, and I was awake because I was too polite to go to sleep when someone was talking to me. The others had heard it all before.

Manuel is a curandero – something between a faith healer and a barefoot doctor. His speciality is bones, muscles and the nervous system. He is known throughout Andalucía and I have heard of his successes from Málaga to Jaén. He is a fine-looking man with a bearing of unpretentious dignity, and despite his tiny frame he possesses an almost supernatural strength as well as a limitless capacity for talking. He sat in front with Baltasar. It was his car, so he was accorded that dignity, although he never would presume to try and drive the thing. Like reading and writing, driving is the province of a younger, more advanced, technologically literate class of person.

As he spoke he twisted round in the tall seat to address me and make sure I was still listening. ‘Well yes,’ he explained when I broke the monologue with a question. ‘There was a doctor in the town shortly after the war, and he didn’t like me practising at all. He made life as difficult as he could, got the Guardia Civil to harass us: he was friends with the town comandante. The church doesn’t like curanderos, you see, and the doctor, as well as being a second-rate practitioner who only attended the needs of the rich people of the town (and that badly) the doctor was a very churchy man. So I could only practise with the greatest difficulty. One winter, the Guardia locked me up in the town jail for three weeks – no heating and not enough to eat – and gave me a thorough beating, too.’

‘But it didn’t make you want to give up the healing?’

‘No, it’s a gift, the healing. Like the gifts of sight or hearing it’s hard to stop using them. People come to me with their pains and their sicknesses and I know I can help them. So I do; I can’t help it. I don’t take any money for it, only what people want to give, but I do get an awful lot of pleasure from it.

‘Anyway, late one night there was a knock at the door. When I opened it I found a woman wrapped from head to foot in a dark blanket. I led her in to the light, and as I turned to look at her I understood why she had covered herself so. She was the wife of the comandante. She told me she was in great pain with her legs; she hadn’t slept for weeks from the pain and the doctor had told her there was nothing he could do.

‘I soon discovered what was wrong with her; it was trapped nerves, the poor woman could hardly walk. I treated her several times during the course of the week – she always came at night and hidden, it wouldn’t do for the wife of the comandante to be seen consorting with curanderos – and at the end of the week she was completely better, not a trace of pain. From then on I never had any more trouble with the Guardia.’

Manuel’s stories were too good to doze through. He told them well, fluently and with a fine sense of balance and dramatic timing. Those who cannot read or write have the advantage in this; the ability to keep a long story in one’s head tends to diminish with literacy.

He launched into another story about what happened to the doctor – of course he got his come-uppance – and I had no doubt that the story was true. Then he moved on to a tale about another doctor. Various people of the town, the butcher Sevillano, the baker, the café owner who had been nursed by a donkey, all wandered in and out of the narrative. He kept up non-stop, wriggling round every few minutes to see that I was still listening. I crouched forward to catch his quiet voice above the thrum of the engine and rumbling of the trailer.

As we turned east and ground up towards the Puerto del Lobo, I realised that the monologue had shifted into new territory. The workaday world he described was being infiltrated by new and unlikely characters. A fisherman appeared on the scene. Lanjarón is high in the mountains and twenty miles inland; one thing it does not have is a fishing fleet. Then came elements that seemed somehow strangely familiar. With some surprise I realised that Manuel had moved seamlessly into the Tales of the Arabian Nights. The jealous doctor and the venal priests were soon eclipsed by a procession of princes and djinns and viziers and sages.

We swung through the main gate of the market not long after midnight.

‘You’re the first here,’ said the half-frozen man in the gatehouse. ‘Five hundred pesetas and you can have a pen right at the top, best position of all.’

‘Marvellous,’ I said, handing over the money. ‘Good thing, getting here early.’ Baltasar grunted. Everyone else was fast asleep.

We pulled across the empty concrete plain of the market yard and stopped by the top row of pens. Baltasar switched off the engine, stretched and groaned. I opened the door to get out and stretch my legs – and immediately closed it again. I didn’t know Spain got this cold. It wasn’t till I read the next day’s paper, which quotes Baza as one of the extremes of temperature for Andalucía, that I found out that it was ten degrees below zero.

Apparently the human body gives off the equivalent of a kilowatt of heat, so five of us ought to have heated up that car like a steam-bath. It didn’t work. Everyone was awake within five minutes, teeth chattering, squirming this way and that, unbearably uncomfortable. ‘Surely there’s a bar or somewhere where we can go and sit in the warm?’

‘Not till later.’

‘Run the engine then, for heaven’s sake, man!’

‘Not now, I can’t keep it running all morning.’

At four o’clock the bar opened. It was ten degrees below outside; it was ten degrees below inside. The bar was a huge, stone-floored, white, neon-lit shed designed to be cool on hot summer mornings. We left the door open; there didn’t seem to be much point in shutting it. The bartender came in, shivering and complaining bitterly. We drank brandies to occupy ourselves while the coffee machine got up steam. The barman went out and returned with some olive logs with which he lit a barbecue in the corner by the kitchen door. We all edged towards it. A couple of girls stumbled in, just out of deep sleep and marginally on the right side of hypothermia. They stood by the now blazing barbecue and surveyed the customers with indifference.

At around four-thirty others started to dribble in. Heavily-swaddled lorry drivers and shepherds. A dealer, noisy in a sharp suit and quilted anorak, holding forth to his entourage of toadies. A short man in a leather jacket and beret limped in and sat on a chair near the fire.

‘You’ve got a nasty limp there!’ said Manuel enthusiastically.

The beret looked at him in astonishment, for although it is the custom in Spain not to deny people their afflictions, it’s not usually done quite so directly. ‘It is a nasty limp,’ he said slowly. ‘And what’s it to you?’

‘I take an interest in such afflictions. I make them better. What’s wrong with the leg?’

‘Well, they’re both bad, been like it for twenty years now. The doctors say it comes from the cold on these mountains and they can’t do anything about it.’

‘Can you straighten them both out like that?’

‘No.’

‘Bend them like this?’

‘No, not that way either.’

‘What you need is to do exercises. I do them every day, and look at me; the cold hasn’t even got to me yet.’

This was not an empty boast since Baltasar’s family have the highest farm on the mountain above Lanjarón, a spot that enjoys truly gargantuan weather, and Manuel has spent most of his life working there. But the man in the beret looked dubious. He wouldn’t do the exercises, I could see that. He hobbled off to get another brandy. Manuel set off to do a tour of the bar and see what other interesting afflictions he could find.

Domingo and I, leaving Baltasar to watch out for Kiki and make sure he didn’t pull some stunt in the market bar, went to pen up the lambs and cast an eye over the opposition. Our pen seemed to be a long way from all the others. The action, such as it was, was taking place at the bottom end of the market. Here there were larger lots of lambs, a hundred, two hundred to a pen. My forty lambs were good, but a little smaller than most, and the fact of their being huddled up in a corner of the pen didn’t show them off to their best advantage.

In the pen next to mine was a mixed bag of old goats, and on the other side a smelly billygoat milling about amongst a small bunch of ill-favoured lambs. Apart from us, all the other pens up our end were empty. It didn’t take a lot of thought to work out that this was where they put the punters who didn’t know the ropes. My neighbours were certainly not out of the top drawer of modern-thinking shepherds.

My five hundred pesetas had rented a concrete pen beneath a huge open shed. Here I displayed my wares to their best advantage, leaning on the door nonchalantly as if it were a matter of complete indifference whether I sold them or not. The dealers moved around the pens with an entourage of note-takers, purveyors of unsolicited advice, toadies and desperate shepherds. The vendors made their own deals with the buyers on the basis of whatever information they could pick up by listening in to the dealing at the other pens.

By six, the lower end of the market was seething with activity. It was the darkest and coldest hour of the night. I thought I had dressed warmly but it wasn’t enough for this. Frozen solid from my toes to my ears, I could hardly talk – I certainly couldn’t get my mouth around sheep-dealing Andaluz. Domingo wandered up from the pens below.

‘Bad news, the prices are getting lower. One of the shepherds in the big pens down there has just accepted seven thousand and his lambs are the biggest and best here. Smaller lambs are going for nothing. Also Luís Vazquez is down there and unless I’m much mistaken he has spread the word that nobody should take any interest in your lambs.’

‘Why ever not?’

‘He was angry because you didn’t sell him your lambs when he came to see you…’

‘Of course I didn’t, not at the ridiculous price he was offering!’

‘Well anyway, he and the other dealers of the Alpujarras are not pleased with the prospect of more shepherds bringing their own lambs to market. It’ll put them out of business.’

‘Good thing too.’

‘Yes, but they’re not going to take it lying down. Luís has been talking to all the dealers here in the market. They’ll want to teach us all a lesson.’

Occasionally, as if to lend weight to Domingo’s words, a dealer and his entourage would break away from the melee at the lower end of the market and saunter up past my pen, look at the lambs with a sneer and pass on without a word. Domingo did his best to engage them in conversation and draw attention to the advantages of my lambs, but to no avail.

I leaned forlornly on the wall, looking at the poor frightened creatures in the pen. How much longer would this ghastly ordeal go on? Everywhere I could see batches of lambs being shoved down the corridors to the loading-bays. Fat-bellied dealers were climbing into their Mercedes and sweeping away through the gates. It looked like I would have to endure the humiliation of taking the lambs home again, a wretched double journey as well as a night of cold and misery for them.

‘We won’t go yet, though,’ said Domingo. ‘It often happens that prices get better towards the end of the market. Perhaps some dealers won’t have made up their quota and there’ll be fewer lambs to choose from. We may be lucky yet!’

We weren’t. The spasm of buying and selling had climaxed and ebbed. A feeble white sun crept up from behind the horizon and illuminated that horrid place with rays devoid of warmth. The big pens of lambs emptied and the big dealers disappeared one by one. In the carpark beside the shed, the village dealers and small-time operators cruised up and down the lines where those too canny to pay the five hundred pesetas for a pen plied their wares. Here were battered Renault 4s, their windows steamed with the breath of a dozen lambs, a goat trussed up and lashed to the back of a tractor, an old man standing forlornly with a couple of thin sheep on a rope. But nobody came even to look at my lambs. I felt lost and lonely, like a new boy at school.

I had a coffee with Baltasar, leaving Domingo to try and drum up some interest among the remaining buyers.

‘It doesn’t look like you’re going to sell them today.’

‘Yes, I suppose I’ll have to take them home again.’

‘You should be a little careful, you know; you’ve made some enemies among the dealers, and they’re bad people to cross. You never know what they might try, not in broad daylight like this but on a dark night on a lonely mountain road…’

He left the sentence unfinished. I thought he was being a little dramatic, but maybe it was serious. I was breaking the mould, sticking my neck out. It was a foolhardy failure. We loaded up the lambs again and headed for home. As we passed through Lanjarón and Órgiva we made frequent stops to satisfy the curiosity of passers-by. Some of them had already spoken to the dealers and they seemed to know already the minutest detail of our humiliating journey.

Predictably enough there was a flurry of interest among the dealers to see if they could get the unsold lambs for nothing. I would have to sell them; it wouldn’t be long before they went past their best, and then I really would have to give them away. The man who gave me the most reasonable deal was a gypsy from Órgiva called Francisco. He was such a small operator that he hadn’t the wherewithal to go to the market in Baza. Domingo told me to watch him, as he was known to be a bad payer, but he paid me in advance as he took the lambs away in four batches of ten over the next month.

I have sold to Francisco ever since, and so far he has not let me down. Now I’ve come to like selling the lambs locally. It’s by far the most ecological option; it saves the lambs a stressful journey, saves on transport costs, and it pleases me to be supplying the community in which we live. Occasionally people will come up to me and compliment me on the quality of lamb they buy at Francisco’s stall in the market. Francisco himself is a firm believer in the superior quality of carne campero.

‘No, this bringing the lambs up on high-protein feed in the dark is a modern notion. In my father’s time as a butcher, a lamb wasn’t considered fit to eat until it had grazed for a summer in the high pasture. The lambs were bigger and older then but the flavour was superb. My older customers complain that they can’t get any good meat any more. The stuff they buy just shrivels to nothing in the pan. So I’m really pleased to see you producing carne campero. I’ll buy whatever you produce.’

It was no October Revolution, leading the shepherds of the Alpujarras to cast away their chains, but for me, perhaps, things had turned out again for the best.