And then what happened?

CHRIS STEWART BRINGS EVENTS UP TO DATE

Ten years on from the publication of Driving Over Lemons, Chris Stewart talks about life at El Valero, what’s changed in his valley, how the success of the books has affected him and his neighbours, and whether he ever regrets leaving Genesis.

Chris, the first thing everyone always wants to know is – are you still living on the farm, at El Valero?

It’s funny how often people ask that. They tend to say: ‘Are you still living on that dump of a farm you describe in the books, or have you moved to some marble-clad villa in Marbella?’

Clearly those people have not read the books! Either that or I have failed absolutely to get the message across. The answer is a crystal-clear yes. After twenty years, we still greatly enjoy living here, and the only way we are leaving is in a box – and not even then, as a matter of fact, as both Ana and I would like to be buried beneath an orange tree on the farm.

Mind you, I do sometimes wonder if we could have stayed at El Valero without the books and the royalties we earn from them. A lot of farmers, and especially organic farmers, find they simply can’t get by without some other source of income. It was pretty fortunate that our source turned out to be writing books.

Do you still feel the same way about the farm as when you moved here?

I had just turned forty when we bought El Valero; Ana was a few years younger. Looking back, it was a good age for a move. We could manage the constant round of work and still have energy left to look about us and make improvements. I can’t imagine starting out on some of those schemes today – fencing off the hillside for the sheep, for example, was an absolute killer of a task.

Curiously, during the first years I grew convinced that the one thing we needed to put everything in order was a tractor – as if it was a universal panacea that would sweep away the drudgery of farm work. I remember thinking, when I was offered a contract for Driving Over Lemons, ‘Maybe, I’ll be able to buy that tractor.’

And when I got my first royalty cheque, I did buy a tractor – a ropey old model which had reached the end of its useful life in Sussex. It was a vehicle that should have been put out to rust rather than shipped to Spain, especially to a farm like ours. I drove it for a few weeks but found it completely terrifying, wobbling and tipping on the tiniest of inclines. Which is the way a hell of a lot of farmers go, with a tractor tipping on top of them. So I’ve kept a pretty wide berth from it ever since.

Did the success of Driving Over Lemons have any immediate impact, beyond buying tractors?

It gave us freedom from daily worries about money – that’s a very welcome thing. It was a relief to no longer be pitied by friends or family, who thought we had been daft to sink all our money into a subsistence farm. And I no longer had to tear myself away from the farm to go shearing in the gloom of the Swedish winter, or do the rounds so much in Andalucía. Not that I regret all those shearing expeditions in the high mountains. They gave me an insight into a vanishing way of life, a ready source of stories, and a lot of local friends. We would have had a very different experience of Spain if we hadn’t needed to go out and find paid work.

The book also carried some sense of vindication of the crazy decision we had taken when we upped sticks and moved here. Even my mother, who had always hoped I would live in a nice Queen Anne house in the south of England, volunteered that she now almost understood what it was that we saw in the place.

Just how tough was it in the early days?

I’m not sure we stopped to think about it. We weren’t exactly hand-to-mouth, as the shearing brought in enough for us to get by on, given that we had the fruits of the farm. We always had fresh orange juice, olives, wonderful vegetables, and an occasional leg of lamb. But we were, I suppose, pretty close to the breadline, which I think did us good. It would be foolish to extol the virtues of poverty, but you can learn a lot from a few years of straitened circumstances. For us, it bound us as a family and rooted us on the farm. We had to make things work because that was how we fed ourselves.

Driving over the river, with Chloë aged about five. The farm really is on the wrong side of the river – and we still have to ford it to get across.

Were you prepared for the book’s success?

Every publisher makes it their first task to tell an author, once they have commissioned their book, that they won’t make a bean out of it. And mine were the same: ‘Don’t give up the day job,’ they said. Not that there was any choice about that. If you’re a farmer, you can’t. I had no inkling that my whole life was going to turn around and the writing would become the thing that I do.

Although your books are sold as ‘Travel’, you actually stay at home!

That’s right. I hardly move from the farm from one chapter to the next in Driving Over Lemons, though the orbit extends to Seville and back to Britain in A Parrot in the Pepper Tree, and there’s a chapter in Morocco in the third book, The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society.

But the main things I write about are the kind of everyday things that happen to all of us, in our different ways. Children growing up and leaving home to become students, as has just happened to us with Chloë. And all the peculiarities of life – the snarl-ups and delights – which are perhaps odder for us because of the remoteness of where we live.

Of course, in Spain, where I have recently been published, they really can’t put my books under travel, so they put them under ‘Self-Help’, along with books on the spiritual path and harvesting your inner energy. Strange bedfellows.

You’ve become a bestseller in Spain over the past couple of years. Have your neighbours now read the books?

When Driving Over Lemons was published, Domingo – my nearest neighbour and the book’s true hero – got his partner Antonia to translate and read it to him… but only the bits in which he appeared. Later, when it came out in Spanish, he read a chapter every night before going to sleep. Of course, he never mentioned this to me, though he told Antonia that he enjoyed the book.

But the funny thing about Domingo is that he is not Domingo at all – he has a quite different name. For many months, as I was writing the book, I would tell him that I was writing a book in which he appeared as a major character. Would it be okay to use his name or would he rather I change it? ‘Me da igual,’ he would say in his typically Alpujarran way; ‘It’s all the same to me.’ I was pleased because I felt I had created an affectionate portrait of a good friend, and it felt right to use his real name.

Well, I asked him again and again, just to make sure, and each time received the same assurance. And then, at the last possible moment, he came up to the house, very animated, and said: ‘Cristóbal, I’ve been talking to somebody who knows about these things and he tells me that I could get into a lot of trouble as a result of this book – legal problems and family problems and God knows what else. So I want my name changed.’

I could see that somebody in a bar had been spreading a bit of mala leche – ‘bad milk’ – as the Spanish put it. I was a bit sorry about it, but he was adamant, so I set about changing the names of all his relatives and his farm, and so on. Of course, anybody local reading the book would still know exactly who Domingo was, but he didn’t seem to mind that. As far as he was concerned, as long as the character was called a different name, it wasn’t officially him.

Lemons and Parrots in Spanish

Then, as time marched on, my-friend-aka-Domingo, inspired and encouraged by Antonia (who, of course, isn’t called Antonia), took up sculpture and started making a bit of a name for himself by creating the most dazzling bronze figures of animals. By this time Lemons was selling like hot buns. And so he decided to go for an alias – and to my great delight chose to call himself, for artistic purposes, Domingo.

What about your other neighbours? What was the reaction like from them?

There was a bit of everything. One woman in Orgiva complained very publicly that I had not painted an accurate picture of the people of the town, ‘because we don’t eat chickens’ heads’. Apparently everything else was fine: it was just the culinary stuff that stuck in her throat, so to speak. Well, having comprehensively researched the subject of chicken head cuisine, I can say authoritatively that some Orgiveños do and some of them don’t. I know this because I’ve had the pleasure of sharing the odd chicken’s head myself.

The locals in general began to register the success of the book because people started to turn up clutching copies. This gave a bit of a boost to the drooping Orgiva economy, which made me popular with the café owners. Antonio Galindo, who owns the bakery, a café, two bars and a discoteca, embraced me publicly in the high street and said I had turned his fortunes around. So that felt good. And not long after, I was honoured to be the recipient of the Manzanilla Prize for Services to ‘Convivencía y Turismo’ (which loosely translates as ‘harmony between cultures and tourism’). This singular honour was manifested in the form of a tin sculpture of a manzanilla (camomile) plant – what the Spanish often call a pongo (as in the phrase ‘Dónde demonios lo pongo?’, which means ‘Where the devil do I put this?’).

News of the award got into the national paper, El Pais, where it was seen by an anthropology professor, who then published a scathing letter stating that I had contributed more to the dilution and demise of Spanish culture than any other single person. That shook me a bit, and a few days later I was stopped on the road into town by Rafael, who farms olives, oranges and vegetables in Tijola, our nearest village. ‘I have just read your book, Cristóbal,’ he boomed. I hung my head to await the worst. ‘You are the greatest writer of the Alpujarra,’ he intoned. ‘You are…’, he paused searching for a very particular epithet, ‘a Rambo of the mind’.

It’s the nicest critical review I’ve ever had.

So is it the people, as much as the farm, that keep you in Andalucía?

Without a doubt. We’ve been made incredibly welcome here. And the Spanish rural way of life suits us. But the land has got into our blood, too. When you spend twenty-odd years building and gardening and planting trees on a plot of land, you develop a connection that runs deeper than the normal sense of ‘home’. All those repetitive chores of tilling, sowing and harvesting exert a subtle influence that affects the essence of who you are. And if you believe that you are what you eat, then we’ve become Andaluz through and through, since for two decades now we have turned the earth and pulled up vegetables, picked fruit from the trees on the terraces we’ve tended, collected and eaten the eggs from the chickens whose care is the first imperative of every day, and eaten the sheep that graze amongst the wild plants that grow on the hills around the house.

And there’s the water, too. Nearly eighty percent of us, give or take a few bottles of wine, is made up from the water from our very own spring – I’ve wondered a little what we look like inside, given the amount of limescale at the bottom of our kettle. But I feel sure this place has seeped into us. We’ve been formed by all the little griefs and agonies, and triumphs and delights, that have peppered our lives since we moved here.

So how could you ever leave a place like this? How could you sell it? How could you put up with estate agents tramping around it with notebooks and snooty clients pointing out loudly how sub-standard and ill-conceived everything is? El Valero was never a buying and selling property. We didn’t buy it as an investment; we bought it as a home. Which is lucky because it may well be the only property in Spain worth less than it cost twenty years before… and I’m glad because I’ve never wanted to sell the place anyway.

What do you think Spaniards in general see in the books? You’d think the humour is peculiarly English.

I thought so, too, and the books weren’t published here for some years. But it turns out that the Spaniards find just the same bits funny as the British. They enjoy the way the rural Spanish are portrayed. I’ve had all sorts of people coming up, some of whom I didn’t know could even read, wanting to tell me the bits they find funny. That said, the urban Spaniards think that we are completely bonkers. Our farm – and the Alpujarras – is very far from the spotless way that most modern Spaniards like to live.

Translation’s a funny thing, though. I was interviewed by two young Taiwanese journalists, who explained to me what a humorous book the Chinese had found Driving Over Lemons. Out of curiosity I asked them if they could translate the title. I know a bit of Chinese and it struck me as peculiarly long. They scratched their heads, then said, ‘Sheep’s Cheese and Guitar Heaven: a Ridiculous Drama of Andalucia’.

What did Chloë think about the books?

Well, she was mystified by the English title! I have a vivid memory of her worried face when she first heard us discussing it. ‘Driving Over Lemons – an Octopus in Andalucía… what on earth does that mean?’ I think she was about seven at the time. So ever since then I have been the ‘Octopus in Andalucía’.

She once said she would much rather I wrote novels: to her, my books are really just diary pieces and too familiar to be interesting. But secretly I think she gets quite a kick out of my success. A few months ago, she went to open a bank account in Granada, and as she handed across her ID card, the woman behind the counter exclaimed, ‘Ay, Chloë Stewart… you must be the girl in the book! Ay, how I loved the book.’ It’s no bad thing to be known at the bank.

Do you think Chlöe – or Ana – might write her own version of life at El Valero one day?

No. Ana has not the remotest desire to write, although she types with style and wit. (And has just reminded me that she might still go into competition with a plot for a ‘body-stripper book’). It’s hard to say with Chloë; I hope that we’ve given her a childhood that could give her something to write about. But right now she’s a university student – and has flown the nest. She shares a flat in Granada and, as you might expect, has euphorically embraced urban life. Nothing is more likely to induce an enthusiasm for all things urban than a country childhood.

So now there’s just Ana and me again on the farm, rattling like peas in a drum. This has been a tough rite of passage, and nobody tells you about it. You spend eighteen years living your life around, and for, your offspring in the most unimaginably close and intimate way… and then they’re gone. There’s nobody to wake in the morning and make sandwiches and breakfast for before heading off to the school bus.

Of course, we get a lot of pleasure from Chloë’s happiness in her new life, and we’re proud of her independence and her making her way in the world. But it’s an odd stage, nonetheless.

What is the menagerie cast these days? You’ve got the sheep, and chickens…

It’s the same old crew really, with occasional losses due to ‘natural wastage’, which of course is where I’m headed myself. The top of the pecking order is the wife, my favourite member of the menagerie, along with Chloë – who still, I think, sees this as her home. Then there’s there the unspeakable parrot, Porca, Ana’s lieutenant and familiar, who arrived by chance to make his home with us about nine years ago. This creature is one of the villains of my second book, A Parrot in the Pepper Tree.

The parrot dominates the five cats, who range far and wide on the farm, feasting abundantly on rats. Then there are two dogs: Big, a hairy terrier we found abandoned by the road, and Bumble, an enormous and amiable mongrel, whose function is to monopolise the space before the fire and bark at intruders. And since we’re so remote and there are few visitors, he and Big keep in practice by barking all night long at the boar and foxes and other nocturnal creatures. Which makes it hard to sleep. The dozen or so chickens earn their keep by providing us, as you might expect, with eggs. And we’ve got a colony of fan-tailed doves, which are on the increase again after a winter when a pair of Bonelli’s eagles reduced their number from around a hundred to just seven. They are more cautious now and don’t go outside much. Paco, my pigeonfancier friend and telephone engineer, is going to get me some stock from Busquistar, up in the high Alpujarra. Apparently those pigeons know how to deal with eagles, because the crags and valleys up there are thick with them.

And finally there’s the sheep, and there always will be the sheep, for I cannot imagine the dull silence of the farm without the bongling of the bells and the bleating of lambs. They provide us with the most delicious meat and, take it from me, eating home-grown lamb is one of the best treats of country life. The flock keeps the grass beneath the orange and olive trees neatly trimmed like a lush lawn. And then they range far and wide on the hills above the house, grazing on the woody aromatic plants that grow there: rosemary, thyme, broom, anthyllis, wild asparagus. At night they return to the stable, and there they copiously deposit the little heaps of beads and berries that, trodden into the straw, make the rich dung which goes to nourish the fruit and vegetables and, at one remove, us. The whole, wonderful circular ecological system.

It sounds like farming is still a passion, even if you’ve become more of a writer than a farmer.

I’ve loved farming since I discovered it at twenty-one, but if truth be told I’m not very good at it. Maybe it is a vocational gift, like medicine or music, neither of which I’m particularly good at, either. I long for the model farm, but under my care weeds seem to get the upper hand, the livestock sieze every chance to destroy the plants, and every agricultural villain seems to be stalking me – mosaic virus, red spider, scale insect, aphids, blossom-end rot. You name it.

Orange trees and sheep – the mainstay of the El Valero eco-system

So it is lucky that, in terms of making a living, I’ve gravitated to becoming a writer. Albeit a writer who spends a lot more time farming than writing. If you’ve spent your life doing physical work it’s hard to take entirely seriously the idea of sitting down for a day’s work at a computer. I still do a bit of shearing, too, which is something I am quite good at – and which nobody else around here can do, except my-friend-aka-Domingo. So at least there’s something that enables me to hold my head up in an agricultural way.

I made a living out of shearing for thirty years, but it’s hard when you hit your fifities, and now I only do a few days a year – my own sheep, Domingo’s, and one or two other jobs in the village. I dread these shearing days because I know what a physical effort it’s going to be. But when I actually get down and stuck in, it’s like dancing a dance you knew and loved long ago. Also, I get to see my handiwork year-round, idling on the hillsides, happily scratching themselves.

And it means that people still know me around the town as the Englishman who shears sheep. I know most of the farmers and they’ll come and holler into my ear in bars. So I’ve got two different kinds of local identities. The sheep man and the book man.

You originally had a peasant farm with no running water, no electricity, no phone for miles around. Are things now very different?

We still rely on solar power, but more and better – enough, in fact, to run a freezer, which is a boon. Meantime, our house becomes ever more ecological. We’ve just installed ‘green roofs’ – a flat roof, lined and covered with soil and drought-resistant plants and grasses – by means of which insulation we have managed to raise the winter temperature in our bedroom to a comfortable six degrees. And we’ve got a solar water heating system that I’m currently working on.

If it weren’t for the great thug of a four-wheel drive parked on the track, our carbon footprint would be virtually nothing at all. That has become of the utmost importance to us… and, at the risk of sounding sanctimonious, so it should be to all of us .

You care a great deal about environmental issues. Do you think your views have become more trenchant since moving to Spain?

I’m not so sure about that. I was a pretty trenchant ecologist long before I moved to Spain. But one of the amazing things about writing a successful book is that people suddenly start to listen to what you have to say. This is rather gratifying, as you may imagine, but it’s not that you are saying anything different. It’s just that you no longer have to raise your voice to be heard. I think it’s the duty of anybody who finds themselves with access to the public ear to use that platform to expound ideas for reducing the sum total of human damage and misery.

Up the mast during an epic trip across the Atlantic, told in Chris’s new book, Three Ways to Capsize a Boat

The building of a dam casts a shadow over both Driving Over Lemons and its sequel, A Parrot in the Pepper Tree. How did that work out?

Well, as you can see, we’re not underwater yet. By great good luck, the authorities ended up building a dam much lower than their original plan, so unless they knock it down and start again the water level will never affect our farm. It is a sediment trap rather than a reservoir, so it’s filling up at a great rate with rich alluvial silt, which is wonderful for spreading on the land. It’s beautiful, too, the way the river meanders amongst the banks of mud, and there’s an aquatic ecosystem developing there, with ducks and herons and legions of frogs.

Talking of water, in your latest book, Three Ways to Capsize a Boat, you leave the land altogether to recall some epic and extremely funny seafaring adventures.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. Yes, Capsize is a book that I had to get out of my system. It seems odd, but I found myself writing snippets of it throughout the last ten years, maybe even longer. It was as if my mind was fixating on the sea. In buying El Valero I had to make a choice between the mountains and the coast. It’s curious how being born and raised in inland Sussex I should come to see these two types of landscape – neither of them prominent around Horsham – as somehow fundamental to my wellbeing.

I chose the mountains, and have lived in them very contentedly for twenty years, but I do have a yearning for the sea, which comes from my early thirties when I had a brief lifechanging encounter. It all started when I talked my way into a job skippering a yacht in Greece – without knowing how to sail. So I had to learn, and one thing led to another and I ended up crewing across the North Atlantic. It marked me for life. Writing about it was fun. I didn’t have any notes, because back in those days I didn’t have the remotest intention of becoming a writer, but many of the experiences I had were so vivid that they all came flooding back. It was a great pleasure, too, thinking myself back to the sea, reliving it in a sense.

The trouble is that it has opened that old wound, and I am now to be found at any hour of the day or night lost in a reverie, staring at pictures of wooden sailing boats and wondering if I ever might own one.

My plan, a new gauntlet that I am throwing down for myself, is to sail around the world before I finally slip away. Not with all the ballyhoo and fol de rol of round-the-world racing and record-breaking. I’m not that sort. For me it’s a matter of ambling slowly around it and wondering at all the terrible, immeasurable beauty of it. Ana indulges these crazed notions with diplomacy and tolerance. I have suggested that she may be permitted a pot of basil on the stern rail in lieu of a farm and garden – and, I suppose, having the beastly parrot along would be most appropriate.

It sounds like you were pretty smitten with the Greek islands, too. You enthusiastically describe sailing to Spetses, before embarking on your Atlantic adventures.

There’s a whole lot to be said for Greece: it has the mountains and the sea in the most glorious combination, as well as the gorgeous influence of Byzantium and the Levant. And its great advantage over Spain is that the Greeks have so far not destroyed the beauty of their coasts and islands. If they do, the old gods will never forgive them.

I could have happily lived in Greece, with its sea and mountains, and the olives and oranges and the Mediterranean climate to go with it. But I always had a romance about Spain, its language, music and culture, and the great cities of Sevilla, Granada and Córdoba. So I have no terrible regrets.

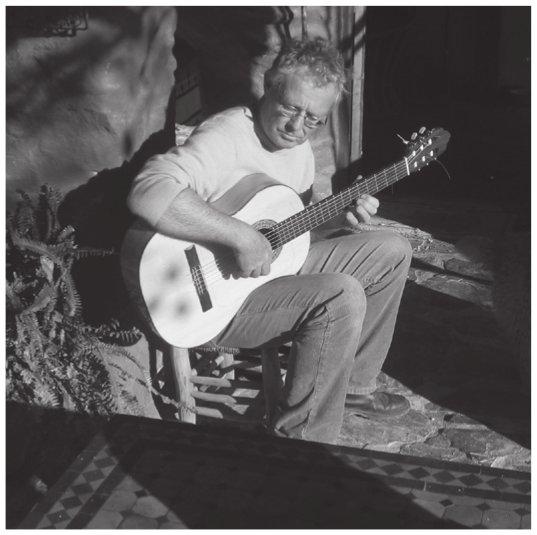

Even the Spanish seem obsessed with Genesis – and my schoolboy career as their drummer. I’m on the right here, pouting next to Peter Gabriel.

One final question that you are always being asked is your role in Genesis. You were in the original band. Can you tell us more about this?

I wrote about this a bit in A Parrot in the Pepper Tree, where I confess that I was never a very good drummer. The other members of the band very sensibly threw me out when I was just seventeen, having played on just two not very good songs on the first album. So I narrowly missed rock stardom. Actually, with me on board I fear that they would have got nowhere – and, once Phil Collins took my place, they did rather well for themselves, for which I’m delighted.

Our paths cross from time to time, and I’m always surprised by how they’ve managed to surf the vicissitudes of celebrity life and come through unscathed. I get the vaguest sense of it even here in Spain, where Genesis have a huge following. I emerged one day from an interview in a recording studio in Madrid to find no fewer than four young recording engineers lined up to shake the hand of a founder member of the great band.

If you could do it all over again, would you still have thrust a wad of notes into Pedro’s hands and bought El Valero?

Without a moment’s hesitation. And, if I’d known things were going to turn out the way they did, I’d have given him double the asking price. If I’d had the money, of course, which I didn’t. I don’t think there’s anything better you can do in the middle of your life than to pick it up and shake it around a bit. Do something different, live somewhere different, talk another language. All that keeps your destiny on the move and keeps your brain from becoming addled. So there you have it – maybe the Spanish are right and Driving Over Lemons really is a self-help book.