Valance “Val” Cull from Port Saunders, Newfoundland, is a steady-as-she-goes kind of guy.

His friends describe him as dependable, fair, hard-working, and very smart, to name just a few descriptors.

Val speaking to audience during award ceremonies at the Atlantic Marine Industries Hall of Fame Awards. Val was awarded in the builder category during the North Atlantic Fish and Workboat Show in St. John’s.

Born sixty years ago, Val lived his first ten years in Great Brehat, on the tip of the Northern Peninsula. When Val was ten, his family moved to nearby St. Anthony.

Val is highly respected in the boat building and repair industry in Newfoundland and Labrador. He got his start by building a small rowboat at a very young age, and then progressed through the many stages of the business to become owner and operator of Northern Boat Repair, a large boatyard in Port Saunders on Newfoundland’s northwest coast.

For years his business concentrated on vessel repair, which included everything vessel owners needed done, up to cutting vessels in two and lengthening and widening them.

People say Val Cull knows every detail of the boat-building business and can do anything on a large or small scale.

Today, he is also known as the builder of a couple of the largest fishing vessels ever built in the province, including the sixty-nine-foot Atlantic Charger, which got caught in a vicious storm in September 2015 and sank near Baffin Island.

Northern Boat Repair is actually one of the few yards building large fishing vessels in Newfoundland these days. At the time of this writing in November 2015, the yard was busy building a seventy-two-by-twenty-six-foot vessel for an enterprise owner in Conception Bay. This boat was the largest build undertaken at Northern Boat Repair.

Val’s early years were fairly typical of boys in Newfoundland and Labrador fishing communities. The son of a fisherman, he spent most of his summer days in his dad’s stage, cutting out cod tongues to sell or pronging fish from the boat to the wharf. His dad, Joshua Cull, also gave Val a little corner of the stage to salt his own fish.

“I remember when I was about eight or nine, the schooner Norma and Gladys was buying salt fish up our way, and they were paying six dollars a quintal.”

Val laughs at that memory, explaining that a quintal is 112 pounds, and $6 translated to about five cents a pound. The pay was so little in the 1950s and 1960s, Val says that his dad and other fishermen often resorted to the barter system and traded fish for groceries and other household needs.

As a teenager, Val fished with his father out of St. Anthony. When Joshua purchased the longliner Wavey Gay, Val fished with his dad in several northern areas, including Black Tickle, Labrador. Val liked fishing, but the northern cod resource was showing early signs of decline, and with fish prices ridiculously inadequate to earn a decent living, he kept an eye out for a different line of work.

He would hang around with anyone building a boat, carefully observing and studying the art of wooden boat construction. He would eagerly offer a helping hand if asked. By the time he was in his teens, Val had acquired the knowledge of most boat-building apprentices.

It seemed boat building would be Val’s destiny.

In 1973, he met Jane Hynes, a young woman from Port au Choix, and before long the two were making long-term plans for a life together. They married in 1974.

Ironically, Jane’s dad, Gordon Hynes, was a boat builder. Val was hired as a labourer and worked alongside his father-in-law at Kennedy’s Boatyard in Port au Choix, and from that day, his corporate destiny was more or less determined.

Fishing vessels were built of wood in the 1970s, and with a vibrant winter dragger fishery on the west and southwest coasts of Newfoundland, there was a fairly consistent demand for repair work and modifications on existing vessels.

There was lots of work, and Val was becoming known as one of the best in the business. It was that recognition by vessel owners that led to a life game changer for Val.

In the late 1980s, Bobby Spence was going to build a new boat, and he wanted Val to do the entire job. The only way that could happen was if Val owned his own company. That was the impetus for the formation of Northern Boat Repair Ltd. Val rented floor space at the government-owned marine service centre in Port Saunders and did the construction job for Bobby.

Val admits he is a risk taker, and in 1992, at the age of thirty-seven, he made a business decision that appeared so risky that some people even called him crazy. He leased the large service centre in Port Saunders to operate his growing repair and building business.

Ordinarily, Val’s business move might not have attracted much attention, but his decision to heavily invest into the boat repair and building industry was the same year the federal government declared a moratorium on cod fishing, which had long been the backbone of the Newfoundland and Labrador fishery.

“That’s why they all said I was crazy,” Val explains. “But I love a new challenge, and this was about as challenging as it could get at the time.”

Val’s foresight and business intuition proved the naysayers wrong, and Northern Boat Repair was soon carrying out a brisk business.

Fishermen diversified their operations and fished different species like mackerel, herring, and others. Adapting from cod to new fisheries subsequently required different fishing gear, and that in turn meant a need for vessel alterations.

Along with an increase in shrimp stocks and the addition of access to a newly discovered northern crab stock, orders for vessel upgrades and modifications poured in. It was also at the time when fibreglass became popular, and dozens of vessel owners wanted glass installed over their wooden-hulled boats.

The introduction of fibreglass was the next game changer for Val. It was a totally new technology to him, but he recognized that he had to adapt or his business wouldn’t survive. He had a team of fibreglass experts come to Port Saunders and teach him and his staff about the proper use of chemicals and all the requirements of fibreglass construction.

Val’s leasing deal with the government included rental of a 200-ton travel lift that had the capacity to lift large vessels, sixty-five to seventy-five feet, in and out of the water. Having one of the largest lifts in the province, Val was soon getting calls from boat owners in other areas, including the Maritimes, especially Nova Scotia.

In 1997, Val decided it was time to make another career change and purchased the service centre, the travel lift, and everything else that went with the government-owned marine service centre.

By then, Northern Boat Repair was well-established with a workforce of more than thirty people, and his regular client base continued to grow. Owning the entire operation outright gave him the flexibility he needed to expand on that growth with greater certainty.

By 2005, Val Cull had defied the odds and won on so many occasions that making one more major life change was less daunting than some previous decisions.

In 2005, in his fiftieth year, Val decided to try his hand at something entirely different than boat building. After a few conversations with Jane and their two daughters, Nadine and Natrisha, Val sold Northern Boat Repair and moved to Alberta.

After being his own boss for many years, Val couldn’t imagine working for someone else, so instead of working directly for one of the oil companies, Val stuck with his construction skills and remained self-employed. At first he secured contracts as a building framer. He framed up houses for home building contractors. Later, on his own initiative, he built a large, high-end house on spec and sold it.

That worked well, so he built more houses and sold them privately. Nearly three years later, he was having second thoughts about the faster lifestyle in Alberta, and the call of home grew stronger every month. His yearnings to leave landlocked Alberta were cemented when he escaped death by what he describes as “just a fraction of a second.”

“I was driving south on a highway near Grand Prairie when a truck going west came barrelling through a red light at more than a hundred kilometres an hour and T-boned me. He struck the front of my truck and totally demolished both our vehicles. If he had hit me a fraction of a second later, he would have struck me dead on and I would have been killed. That was about when I decided it was time to go home.”

Not long after that incident, Val and Jane packed their things and moved back to Newfoundland. Ironically, the shipyard was for sale again, and Val bought it back. He is still working there.

Val still suffers some physical discomfort from the accident, along with recurring nightmares.

Meanwhile, home had no shortage of close calls for Val, either.

He was about one year old when he first narrowly avoided death. His father came home from working in the woods one cold winter’s evening in Great Brehat and was told that Val had died. Val recounts the story in his matter-of-fact manner of storytelling.

“My grandmother had me laid out for dead. It was at a time when measles, whooping cough, and all kinds of stuff like that was on the go. She looked at Dad and said, ‘Your son is gone, Josh.’ So, with that, Dad ran upstairs where I was, and he picked me up and opened up the big window in the room and held me outside. It was about minus twenty degrees, and I suppose shock of the bitter cold opened my pipes and lungs or something, and a big gasp of air went through me.”

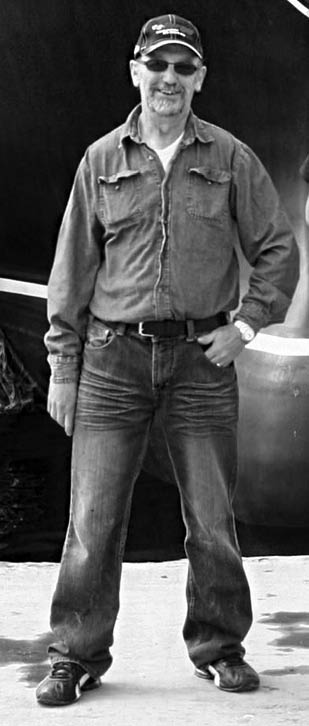

Val on the deck of a new longliner construction at the yard in Port Saunders.

After some careful home care nursing techniques, Val made a full recovery.

Val says that was his first close call of what would be many. His next close encounter came five years later, when he fell overboard.

“I fell from the wharf and, unable to swim, I sank to the bottom. One of Dad’s sharemen saw me on the bottom and dived down. By the time he got me up, I was almost gone. That was my second close call, and I was still only six years old.”

Val has had so many hair-raising brushes with death that he is reluctant to talk about all of them, but one of the closest happened at the boatyard.

“A large piece of plywood got jammed in a heavy industrial table saw in the yard, and it let go and went flying through the air. That piece of plywood struck my chest bone with such force it drove me about twenty feet backwards across the floor and popped my heart right out of its socket. I remember feeling really cold, and two weeks later at the ICU in St. Anthony, they told me that my heart stopped beating and the blood stopped circulating, and that’s why I felt cold.”

On another occasion, Val nearly got shot to death.

“We had been duck hunting, and this guy was walking up from the beach about ten feet behind me. He had a brand new hammerless double-barrel and he had the shells left in, and something happened and the gun went off, and the shots just missed me—I felt the wind on my face from the shot as it went by me. And then, the shot hit a mudbank right in front of me, and mud came flying back into my face.”

He wasn’t hurt other than being a little shook up.

Listening to Val recount some of those amazing stories is reminiscent of childhood days when outport boys would gather in a shop or some place where elderly men would congregate and spin yarns. When asked if he has any more, he answers, “Yes, there are more, but I think that’s enough for now,” he chuckles, saying something about how no one would believe him if he told all of the stories. With a little extra plea, Val consented to just one more yarn.

“Well, not one like the others, but a couple of years ago we were at the cabin, and this young inexperienced guy had a gun pointed straight at me. I don’t know if he realized it or not, but it was loaded and the hammer was cocked, so all he had to do was accidentally touch the trigger and I’d be a goner. I didn’t want to move quickly or say anything that would cause him to make a sudden move, so I slowly reached out and moved him aside and took the gun away.”

Val says that might not sound like a big deal, but when you see a loaded high-powered gun with hammer cocked and pointed directly at you just a couple of feet away, you need to take a deep breath and move gently to get out of harm’s way, and get the gun away from there and disarm it.

Val bought a motorcycle recently and enjoys riding. He says he hopes nothing goes wrong that would use up another one of his apparent nine lives.

Meanwhile, feeling lucky that he’s escaped so many close calls, Val has put the wheels in motion to wind things down and get ready for retirement.

At the time of this writing, Val was finalizing details to sell the yard once again, and as part of the deal, he will stay with the company for a couple of years to ensure a solid transition for the new owners.

“That’s why I wanted to do it now,” Val explains. “I figure if I wait till I’m sixty-five, it would mean I’d be sixty-six or sixty-seven before I could be fully out.”

Whatever his age at closing time, Val can look back at a job well done and a life riddled with near misses that will probably help him appreciate retirement a little better.