“We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea, whether it is to sail or to watch—we are going back from whence we came.”

— John F. Kennedy

Red Bay, Labrador, is best known these days as a UNESCO World Heritage Site showcasing a Basque whaling station that was active there almost 500 years ago. Because of that designation, the southern Labrador community is now world-renowned.

In the 1500s, the shores of Red Bay were part-time homes to hundreds of Basque whalers who hunted bowhead and right whales for blubber, which were rendered into oil for export to Europe.

On Saddle Island, located at the mouth of the harbour, remnants of whale oil rendering ovens and cooperages still sit where Basque hands first built them. Today, you can wander around the former whaling town and immerse yourself in that dynamic history.

You can visualize the day the San Juan sank in 1565 and stand at the whalers’ burial ground where 140 colleagues and friends were carefully laid to rest.

For tourists captivated by the Basque whaling activities, the town is a fascinating link to a mystical life nearly 500 years ago, but for fifty-eight-year-old Wade Earle, Red Bay is simply home—a place of joyous childhood memories, but also a place of dark and haunting memories that troubled him for much of his adult life.

In the 1980s, Wade fished with his father, Edward Earle. In 1987, Edward had been suffering back problems and worried that salmon fishing would aggravate his problem even more.

Hauling and setting nets from a small speedboat was extremely hard work. Most of Red Bay’s fishery was carried out in small boats like the twenty-two-foot flat-bottomed boat Edward and Wade owned.

There were no powerful hydraulic systems to do the heavy lifting. Edward knew that the additional wear and tear on his weakened back could seriously aggravate the problem and cause more damage.

After reluctantly coming to terms with the fact that he would have to sit out the summer fishing season, Edward told his son that he should look for another crewman.

Wade was thirty in 1987, and one of his friends was twenty-one-year-old Leslie Dumaresque who was also a relative and, despite his relatively young age, was known as a good and hard-working fisherman.

As a father of a two-year-old daughter, Leslie was a very responsible and dependable man, and Wade knew he would be a great asset to his fishing enterprise. The two men chatted, and after Wade told his young friend the situation with Edward, it was soon decided that Leslie would fish with him that summer.

The commercial salmon fishery in the Red Bay area of Labrador was carried out in the many various bays and inlets up and down a stretch of coastline, as far as twenty or more miles away. Crews consisted of only two or three men, and most had small shacks or “stations” set up in their chosen location to provide shelter for the season.

Crews would fish from Monday to Friday evening or Saturday morning and go home for the weekend. If catches were good, the men would have to travel to the local fish plant just about every other day to land their catch, because salmon shouldn’t be kept on ice for any longer than a day or two to maintain top quality.

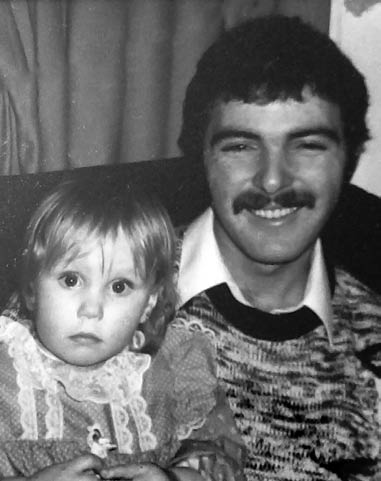

Leslie Dumaresque with daughter Jenna.

Wade and his father had fished in a small location known as Green Bay, eighteen miles north of Red Bay. A couple of other two-man crews also fished in the same cove alongside the Earles.

On Monday morning, June 8, 1987, Wade and Leslie left Red Bay at approximately 5:30 a.m. About an hour later, they arrived at Green Bay.

It was early in the season, and the men were anxious to check their salmon and lumpfish nets after the weekend soak time.

Wade recalls there was hardly any wind that morning, but a sea was heaving up from the northeast. The entrance to Green Bay was always tricky to manoeuvre in seas like that.

The water was very shallow at low tide, and with rocky shoals on the east side of the mouth of the bay combined with a sandy bottom, seas were often confused—not following any regular pattern—and difficult to read.

To get to their cabins, they had to transit the mouth of the bay to brackish water where a river flows into the bay. Mainland Canadian and foreign tourists would pay big money to spend time in a place like that, but for everyday salmon fishermen in Labrador it was just a good sheltered place to build their summer stations.

Because of the rock and sand formations, combined with fast tides in the shallow waters, fishermen usually picked certain times of day to go to and from their cabins.

“We always tried to go in and out on rising or high tides,” Wade said.

The boat ride to Green Bay on Monday morning was as good as it gets. Sunshine and practically no wind made it like a pleasure cruise instead of work. Things were going well as Wade and Leslie checked their nets and set them out again.

Two other crews were doing the same thing. Harold Ryan and his son Warren Ryan were nearby, as was Clarence Yetman, along with his nephew Gregory Yetman.

Both the Yetmans and the Ryans were friends as well as neighbours in their Green Bay fishing stations.

After working all morning, the crews went to their cabins for a snack and to plan the rest of the day. One item on the agenda was a short trip to hunt birds.

“Me and Clarence went out the bay and got a meal of white-wing divers [a local saltwater bird]. We went back in, and the boys cleaned the birds. Leslie was a good cook, and he said he’d cook up a feed the next evening—Tuesday,” Wade says.

It was customary for the crews to get together in one of the cabins after a hard day of work while someone cooked up a meal, and afterwards sit around and have a chat before bunking down for the night.

Late Monday afternoon, Wade and Clarence worked on one of their nets. Greg and Leslie decided to join them, but Clarence was aware that the seas and tides warranted close attention at that time, so he suggested that Leslie get in the Yetman boat with Greg and said that he would join Wade, as the two more experienced of the four fishermen would work on the net.

Sensing that things could get a little tricky in the shallow water with a strong sea running, Clarence gave a stern warning to the two young fellows to stay offshore, where waters were calm.

“’Whatever you do, stay outside. Don’t come in, and we’ll be back out soon.’”

In fact, they were out sooner than expected.

The plan was to secure a shorefast—a ringbolt anchored to a rock to secure the net line to the shore—for one of their nets, but the seas quickly foiled that idea.

“A big sea rolled in over the rock. The swell came back out, and we just about swamped right there and then. We were lucky. We got out of it and left without saying a word,” Wade recalls.

No words were necessary—both men were experienced enough to know that those sea conditions were not to be taken lightly, and it would be foolhardy to try to land Clarence on the rocky shoreline and then get him safely back on board the boat after securing the shorefast.

Monday ended uneventfully, but the experience with the rough seas that evening was a reminder that even when things appear perfectly normal, fishermen need to be keenly aware that the Labrador Sea can get nasty in a split second.

The next morning, the Labrador Sea would show them just how nasty and how deadly it could get.

Tuesday, June 9, 1987, dawned a nice Labrador morning, and except for the same kind of bumpy sea that caused some concern the previous evening, it looked to be a fair day for fishing.

The fishing crews of Ryans and Yetmans, along with Wade Earle and Leslie Dumaresque, were up bright and early, cooking breakfast before heading out to their salmon and lump nets. Harold and Clarence left their cabins a few minutes before Wade and Leslie were ready.

As Wade was putting on his rubber boots, he asked Leslie to pass him his rubber jacket.

“When I turned around he was holding out a life jacket to me. I looked at him and told him I couldn’t wear that because I couldn’t clean and switch nets with that jacket on. Well, he looked at me and said, ‘With the sea that’s on this morning, I don’t think we’re gonna switch very many nets—I’d feel better if you put it on.’”

Wade paused for a second and remembered that Leslie never got into a boat without wearing a life jacket. Knowing it was the right thing to do, he eventually agreed. “Okay, I’ll put it on,” Wade said, and the two headed for their boat.

Wade Earle had no way of knowing it at that moment, but that life jacket would become the most important thing in his life just a short time later that morning.

Shortly after Wade and Leslie left their cabin and were into the open waters outside Green Bay, they saw Harold and Warren Ryan coming back. By the time Wade had arrived at their first net, Harold pulled his boat alongside and said there was no point going out any farther, because the seas were rough and the best thing to do was head back to the cabin before the tide would be too low to get into the brook.

“Okay, we’ll just clean up this net here and we’ll come on back,” Wade said to his half-brother.

Just as Leslie and Wade finished working the net, they saw Clarence and Gregory coming toward them. Clarence echoed Harold’s sentiment that it was too rough outside to work on any more nets, so Wade decided to join his friends and head back to the cabin and wait until sea conditions improved before tending more nets.

By then, Harold and Warren had already arrived safely at their cabin. Suddenly, Harold felt a strange nagging sensation. He felt a need to walk out on a sandbar and watch for the other two boats.

There was a big sea running, and with a falling tide, the shallow waters at the entrance to the brook were getting rougher. Although he had fished in that same area for more than twenty years, Harold did something he had never done before—he went out on the bar and, after catching the attention of Clarence and Wade, Harold attempted to spot his friends safely into the brook.

Wade remembers thinking that, although it was somewhat unusual behaviour for Harold, it was good to have him keeping an eye on the wider view to help them through the brook’s shallow entrance.

“You know how the big waves usually come in threes, and then there’s a lull before more come in, right? Well, Harold could see what was going on behind us and all around us, and so this time, after the third big one went by, he waved for one boat to come on in, so Clarence and Gregory went ahead and got into calm water in the brook, and then we would be next,” Wade explains.

It wasn’t long before Harold observed another set of three large waves breaking, and he signalled that it was time for Wade to get ready to ride the surf and make his entry to the brook after the third and, hopefully, the last big one had rolled in. But it seems this time there were more than three big successive waves cresting in toward the brook. Wade remembers every detail of what happened next as if it were yesterday.

Red Bay

“We were in a fibreglass flat-bottomed boat. I had a fifty-five-horsepower motor on her. I was standing with the handle of the motor between my legs and one hand on the handle. We never got very far before I felt one wave give me a push. I glanced over my shoulder and I saw that I was sittin’ on a wave at least twenty feet high, maybe higher—the boat made a sharp cut sideways, and that was it. Next thing I knew, I was sittin’ on the bottom.”

As in many cases when the human brain is subjected to sudden and intense trauma, Wade’s recollection of the next little while is a sequence of a totally surreal set of events or, as Wade describes it, “weird.”

“It was totally weird. It seemed like I was sitting there on the bottom for an eternity, but even with the life jacket on, somehow I couldn’t move. I wasn’t short of breath; I wasn’t panicking or anything—it was like someone had me pinned to the bottom and I couldn’t get up. I was just sittin’ there looking at bubbles bouncing along in front of me, back and forth. I could see the sand rushing in and out with the tide and wave action. It was just a very strange, weird feeling,” Wade recalls, speaking softly, seemingly reliving the moment again twenty-eight years later.

The “eternity” ended as Wade managed to roll himself over from his sitting position to lie face down in the ocean. With the help of the life jacket, he floated to the surface, and he was surprised to find that he could actually stand on the bottom and that the water level was just above his waist.

That’s when Wade’s thoughts turned quickly to Leslie. His fishing partner and friend was nowhere to be seen.

“The first thing I did was to look and see if I could see him. I could see the boat—she was bottom up—and I could see the sea coming in and coming down right on top of the bottom of her, but I couldn’t see Leslie anywhere.”

Wade figures he was about 200 to 250 feet from the beach where the boat was located. Not knowing where Leslie might have surfaced, Wade intuitively pushed himself through the water toward the capsized boat, all the while calling out to Leslie, hoping to hear a response. There was nothing, at least not then.

“All I could think about was Leslie, because he was not only my friend—we grew up together, we fished together, he was my stepsister’s son, and he was the closest thing you can get to being a brother—he was family.”

Unable to see Leslie anywhere in the rough seas, Wade pushed himself through the waist-high water toward the overturned boat as fast as he could, all the while calling Leslie’s name. What happened next is as vivid in Wade’s memory today as it was twenty-eight years ago.

“When I finally got to the boat, I sang out again and I’m sure I heard three knocks—thump, thump, thump—and I still say it was Leslie. I walked around the head of the boat and around to the outside and reached down with one hand to grab hold of ’er. The boat was down flat on the sand on the bottom, so I reached down with my other hand and lifted the boat—I brought her up across my chest, and when I did, Leslie floated out from underneath, face down with his floater on. I let the boat go and grabbed him by the shoulder and got him on his feet, and when he stood up he was looking me right in the face. I said, ‘Oh my God, I’m some glad to see you.’ I thought he tried to say something, but I don’t know for sure. Looking back on it now, it might have just been water and air coming from his lungs or whatever, but I thought he was alive, so I picked him up and started walking to the shore.”

Wade pauses at this point to explain that some people doubt his account of lifting the boat. They argue it defies logic that anyone could lift an overturned twenty-two-foot speedboat out of the water. He says he understands his doubters, but maintains that although he can’t explain his extraordinary strength at that moment, he swears that it is exactly what happened.

Actually, Wade’s account of that incident is not rare. We’ve all heard many stories about people performing what can only be described as superhuman feats when involved in extraordinarily stressful and traumatic conditions.

Whether Leslie was still alive when Wade was carrying him to shore is not known. But a few minutes later, Wade says, an already dire situation got worse.

“When I got about halfway in, Greg and Clarence came out in their speedboat to help. I tried to get Leslie aboard the boat, but seas were rough and the boat got pushed up on a wave, and when she came down, she hit Leslie, and he fell backwards and knocked me back with him. He was on top of me, and then the boat was pushed in over the top of us again, and this time Leslie was torn out of my arms. When I got back on my feet, I ran over to Leslie, and his floater was keeping his face above water, and I just had enough strength left to keep holding up his face. The water was only just above your knees, so Clarence jumped in the water and picked up Leslie and ran with him in his arms. Leslie was about 185 pounds and soaked, but still Clarence managed to run with him, probably 150 yards, to where Harold was on shore. The boys ran up to the cabin and got sleeping bags to wrap around Leslie while Harold and Clarence tried to revive him. By the time I dragged myself to shore, they had Leslie put on board the boat to get him to hospital, but they wouldn’t let me come with them, so I got in the boat with the other two guys and we followed behind.”

Wade says seas were rough and that it was almost miraculous that they all didn’t swamp on the way to Red Bay.

“There was a sleeping bag in the front of the boat I was in, and it was floating around in water,” he says.

On the way to Red Bay, Wade didn’t know whether Leslie was alive or not. He says he kept telling himself that Leslie had survived, although when Clarence tried desperately to resuscitate Leslie during the trip to Red Bay, there was no response.

“We didn’t know until we arrived in Red Bay, where someone on the wharf was waving us to a different wharf, and that’s when we were told that Leslie didn’t make it. I heard afterwards that he had an injury on his head, so he might have been struck by the boat.” Wade says it could have occurred in the initial capsizing in Wade’s boat or when Clarence’s boat was thrown on top of them.

Whatever the precise cause of death, what is certain is that twenty-one-year-old Leslie Dumaresque died on June 9, 1987, leaving behind a young wife and Jenna, his two-year-old daughter.

Losing such a close friend had a huge impact on Wade Earle.

He remembers the pain of having to sit and explain to Leslie’s family and his own people what happened that fateful day. He also recalls hearing the rumours of townsfolk that started just days after the accident.

Although the gossipers knew little or nothing about the actual events of that day, some of the things circulating around town were very hurtful because they suggested carelessness or even worse.

Wade also had a classic case of survivor’s guilt. He remembers torturing himself wondering what-if.

There were times he needed to sit and talk about it, but he found people were reluctant to get involved and would avoid him.

Wade continued to fish for several years, although he never went back to Green Bay or the location where the accident happened. Years went by, and he found himself sinking emotionally into a dark place—a place where he says “a forty-ouncer became my best friend.” Friends didn’t want to talk to him about the tragedy because it was awkward for them, so Wade was left alone to work through the emotional chaos that was going on in his head.

Finally, several years after the accident, a friend told Wade about a counsellor in West St. Modeste and suggested he should see her.

Wade was hesitant at first, but he eventually agreed to make an appointment with the counsellor, who also happened to be a nun.

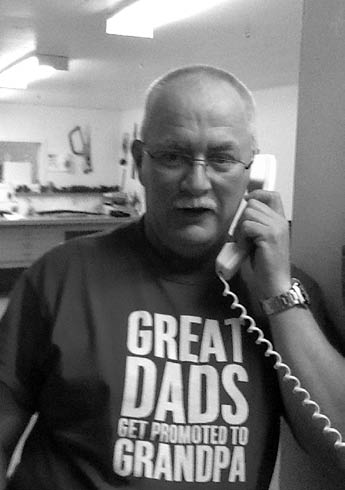

Wade Earle

“You know, it’s funny, but men often think they have to solve all their own problems by themselves, and I must admit that the first few times I went to see Sister Marjorie, I’d wait in the parking lot until I thought no one was looking and would see me going in there. Well, let me tell you, after two or three months I was almost out there advertising the fact I was getting counselling, because I was finally getting better. That lady is not just a nun, she’s a saint, because I don’t know if I’d be here now if it wasn’t for her.”

Wade says he will always hold himself responsible for Leslie’s death, although it was an accident. He has made a lot of progress in finding some level of closure—one step at a time. He named a son, born years later, in Leslie’s memory.

“Some people didn’t like it, but I tried to tell them that it wasn’t a case of trying to replace Leslie—it was merely a way of honouring him.”

It’s been twenty-eight years since Leslie died, and Wade has suffered many years of torment about the incident.

He is a different man than he was before the accident, but he says he is a better man now and pays tribute to Sister Marjorie every chance he gets.

“She saved my life—it’s as simple as that,” he says, all smiles.