1356 |

Professional Writing for Corrections Officers |

Working in the field of corrections, it’s very important to have the ability to accurately express incidents, both in verbal and written communications, so that those who were not present can visualize the incident and understand the necessity and reasonableness of the actions that were taken to resolve the situation.

—Warden Sergio Desousarosa, Rhode Island

Department of Corrections

What you will learn in this chapter:

• The types of writing and the writing process for corrections officers

• The attention to detail required for clear and precise writing

• The opportunity to comment and improve on actual documents from correctional officers

Corrections officers (COs) have demanding jobs. It may come as a surprise that report writing is one of the most important skills in a CO’s repertoire. In addition to describing inmate infractions, ranging from minor violations to serious offenses, COs must document episodes that involve the use of force against an inmate. The written report is used to determine whether the officer’s actions were justified. In 2012, www.corrections.com reported that COs recognize they often need help with a variety of writing skills, including grammar and sentence structure (ToersBijns, 2012). As with police officers, what they write will be read by their superiors up the chain of command, including legal personnel, and how they write will ultimately impact their professional career.

Some departments of corrections have online databases with drop-down menus to help support the officers who need to document inmate infractions that occur throughout the course of a shift. This is helpful given that officers typically do not have much time on their shifts to sit at a computer when they have to be at their posts. These drop-down menus are helpful and do expedite the documentation of more routine inmate 136violations, but they do not substitute for a complete and professionally written report. The www.corrections.com website report adds that,

Officers must avoid “cookie cutter” reports that serve no purpose and only provide attorneys the “bullets” to tear the validity of the report apart. Sharing or copying reports should never be encouraged or instructed by supervisors as the value of the report is degraded when such action exists and is exposed or revealed by other sources such as district attorneys or defense lawyers who will attack the credibility of the writer if written in synchronization with other reports submitted at the time of the incident.

Officers interviewed for the www.corrections.com article offered the following guidelines for reporting:

• Cover the who, what, when, where, and how (if known).

• Carefully follow up with the type of action(s) taken to handle or manage such an incident.

• Do not overwrite (unnecessary or redundant words, sentences, paragraphs).

• Do not underwrite (omitting essential information).

• “(D)on’t use words that are extravagant or fancy.”

• “(S)tick to the facts.”

• “(S)pell check (and review) the entire document to make sure that it is both readable and structured in a format for the reader and purpose designed.”

There is one common factor that could in fact enhance or improve an officer’s performance and the agency’s standpoint in their battle to fight frivolous litigation in this business. One such focal point [is] good report writing for correctional officers and other staff inside prisons. It appears that we have not moved forward a bit in this area in the last few years and some even feel we have lost ground in the importance of good report writing.

—www.corrections.com/news/article/30175-report-writing-for-correctional-officers

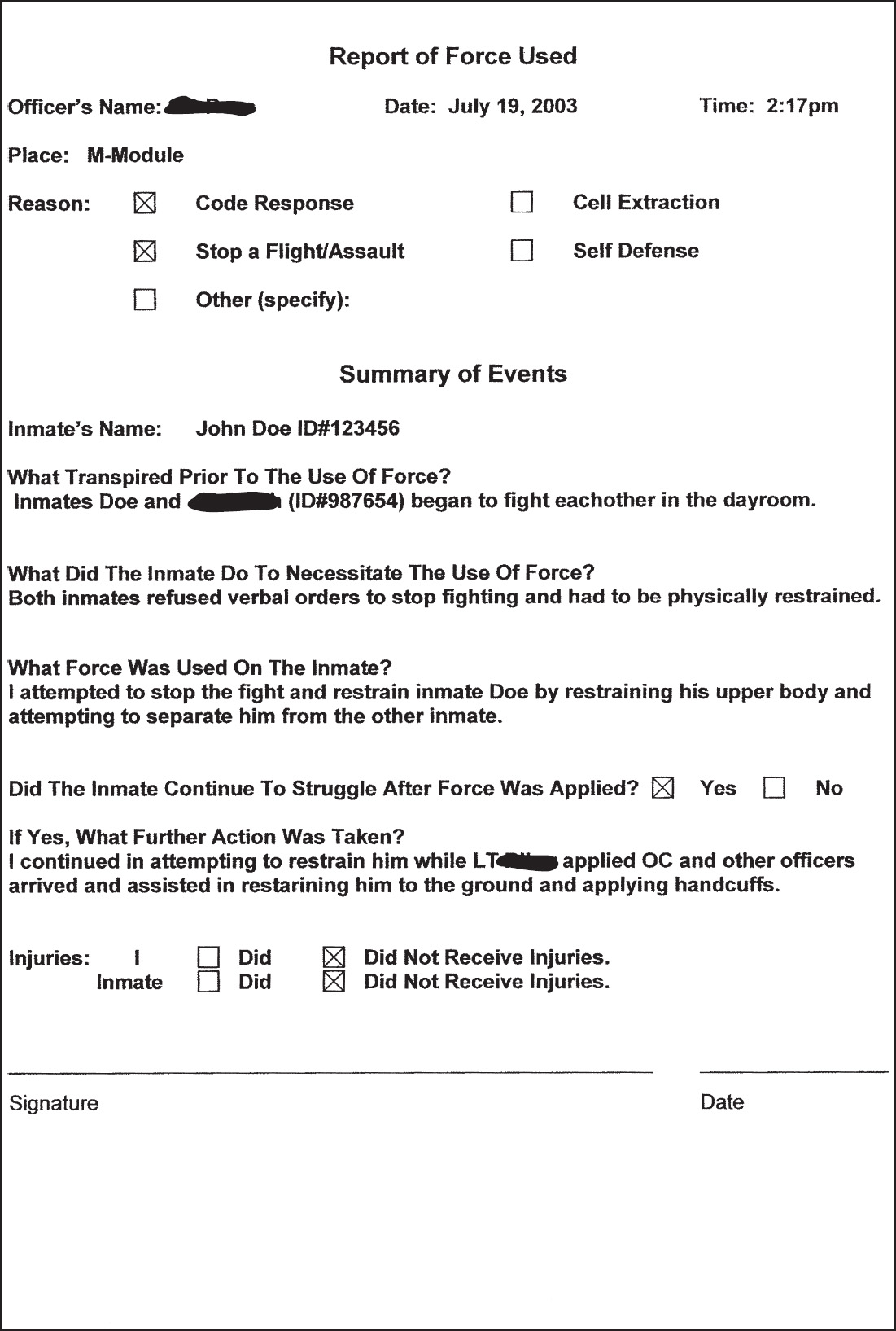

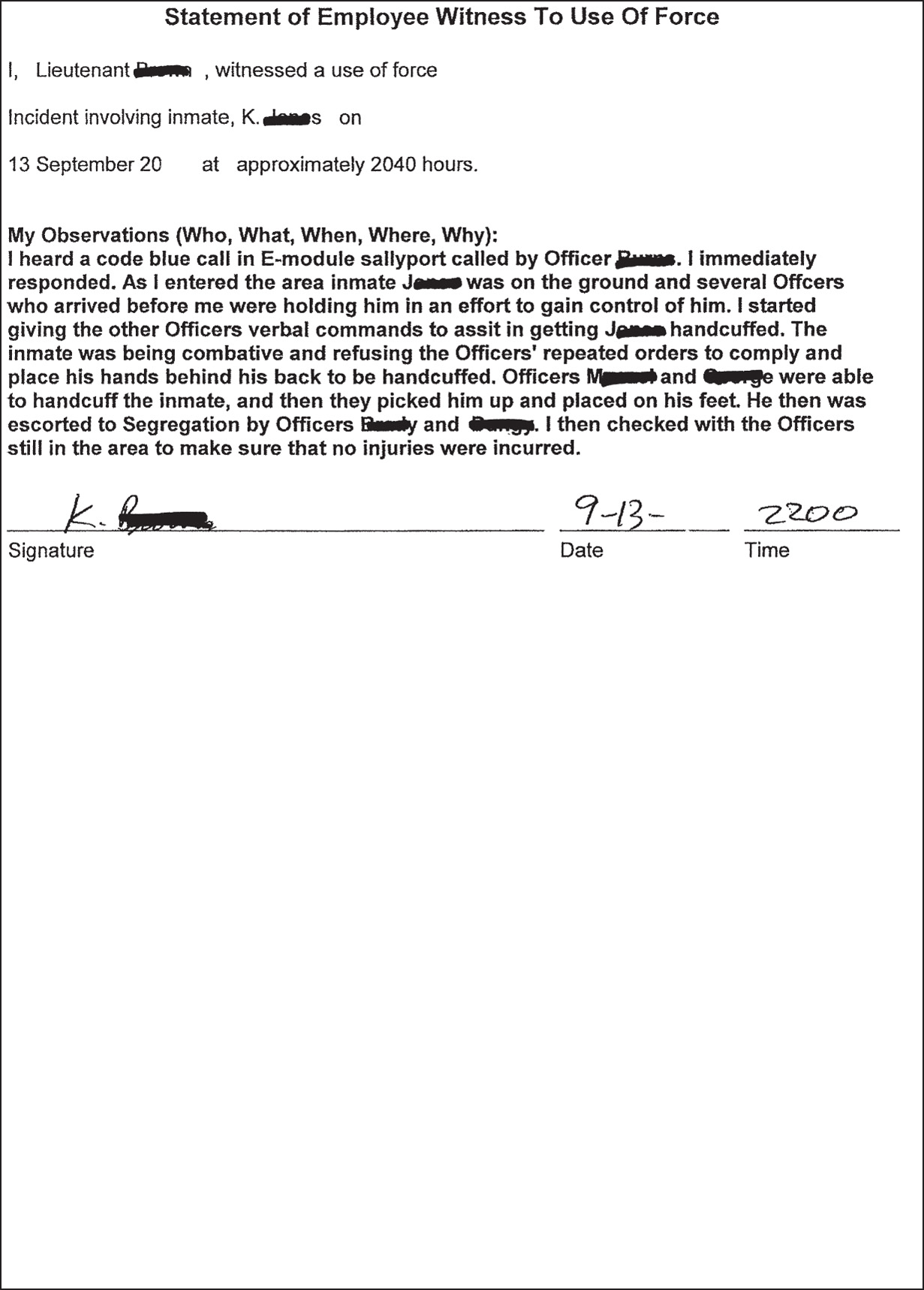

In this section, we focus on one of the most important documents that correctional staff may need in their career: The witness report on the use of force against an inmate. Why is this so important? Consider the following quote:

Litigation costs the corrections institution precious resources that it cannot afford to spend frivolously. Writing effective witness reports is a direct and practical way for you to protect yourself, your colleagues, and the inmates of your facility. Get it done right.

137 Original Report: Statement of Employee Witness to Use of Force

Original Report: Statement of Employee Witness to Use of Force

“I, Lieutenant Gold, witnessed a use of force incident involving inmate C. Downs, on 13 September 2012 at approximately 2040 hours. I heard a code blue call in E-Module sallyport called by Officer Burnham. I immediately responded. As I entered the area inmate Downs was being guided to the ground and several Officers who arrived before me were holding him in an effort to gain control of him. I started giving the other Officers verbal commands to assist in getting Downs handcuffed. Once he was handcuffed, He was guided to his feet by Officers Maise and David. He was then escorted to Segregation by Officers Thoms and Durgen. I then checked with the Officers still in the area to make sure that no injuries were incurred.”

Explanation of Corrections

When this report arrived on the warden’s desk, the warden was not satisfied with the clarity of the report and asked Lieutenant Gold to rewrite it. The warden explained to the lieutenant that his observations of who, what, when, where, and why were not satisfied. What is more, the lieutenant’s narrative was not synchronized with the video camera that recorded the event. How many officers and inmates were there? If the inmate was combative, how could he be guided to the ground? As the video showed, how could he be guided to his feet if still combative and handcuffed? Any jury watching the video, according to the warden, would not use the word “guided” to explain the way the officers took the inmate down to the ground. The warden said that such a statement might become suspect and may infer that the actual event of getting the inmate under control and restrained was much rougher and more aggressive than described.

The lieutenant’s revised report contained the following additional statement: “The inmate was being combative and refusing the officers repeated orders to comply and place his hands behind his back to be handcuffed.” Yet, once again, the warden was not satisfied with the report and felt that it needed to be revised. His chief complaint was that it was not precise enough to withstand legal scrutiny. Lieutenant Gold returned to his desk and tried again.

138 Revised Report

Revised Report

“I, Lieutenant Gold, witnessed a use of force incident involving inmate C. Downs, on 13 September, 2012 at approximately 2040 hours. Officer Burnham called a code blue in E-Module sallyport. I immediately responded. As I entered the area, inmate Downs was visibly combative. He was trying to punch Officers Maise and David with both fists. Officers Maise and David were ordering him to calm down, so they could handcuff him. Inmate Downs refused to comply and continued swinging at the officers with his fists. Officers Durgen and Thoms approached from the rear, held the inmate from behind, and brought him to the ground. The inmate continued to be combative, striking out with his legs. He kicked Maise and David, who were in front of him. I started giving the officers orders to turn him on his side to handcuff him. These four officers held him to the ground in an effort to gain control of him. They turned him onto his right side and got the handcuffs on him. At this time the inmate continued to be combative, resisting the handcuffing by clenching his fists and trying to wave his arms in different directions. He continued to kick at the officers, even when he was on the floor. Two officers physically placed inmate Downs’ hands behind his back while one held his legs and the other held his chest. Once Downs was handcuffed, Officers Maise and David pulled him to an upright position. He was then escorted to Segregation by Officers Thoms and Durgen. I then checked with the officers involved to determine if they had injuries to report.”

In the lieutenant’s first two Witness to Use of Force statements, his narrative did not adequately describe the severity of the incident. Most importantly, it did not describe the effort the officers went through to restrain the inmate, who was visibly combative and refused their commands. Once the original report arrived at the warden’s desk, he expressed concern that there was not sufficient information about the inmate’s behavior, especially if the inmate later alleged that the use of force was unjustified.

In the revised version, the lieutenant described the inmate’s behavior and the entire episode in sufficient detail that the event would be understood by the officer’s supervisor, and, if necessary, legal counsel, a defense attorney, and a judge. Furthermore, the lieutenant’s report needed to be synchronized with the Use of Force reports that would be submitted by officers Maise, David, Thoms, and Durgen, who were also involved in the incident.

Note that the final narrative followed a chronological sequence, and avoided judgmental and pejorative language. Lieutenant Gold supported every characterization with a description of the inmate’s behavior (e.g., “continued to be combative”. . . “clenching his fists and trying to wave his arms in opposite directions”). The report contained very few adjectives or adverbs. It was straightforward and sufficiently objective that a reviewer would take it seriously. Finally, there were no writing errors.

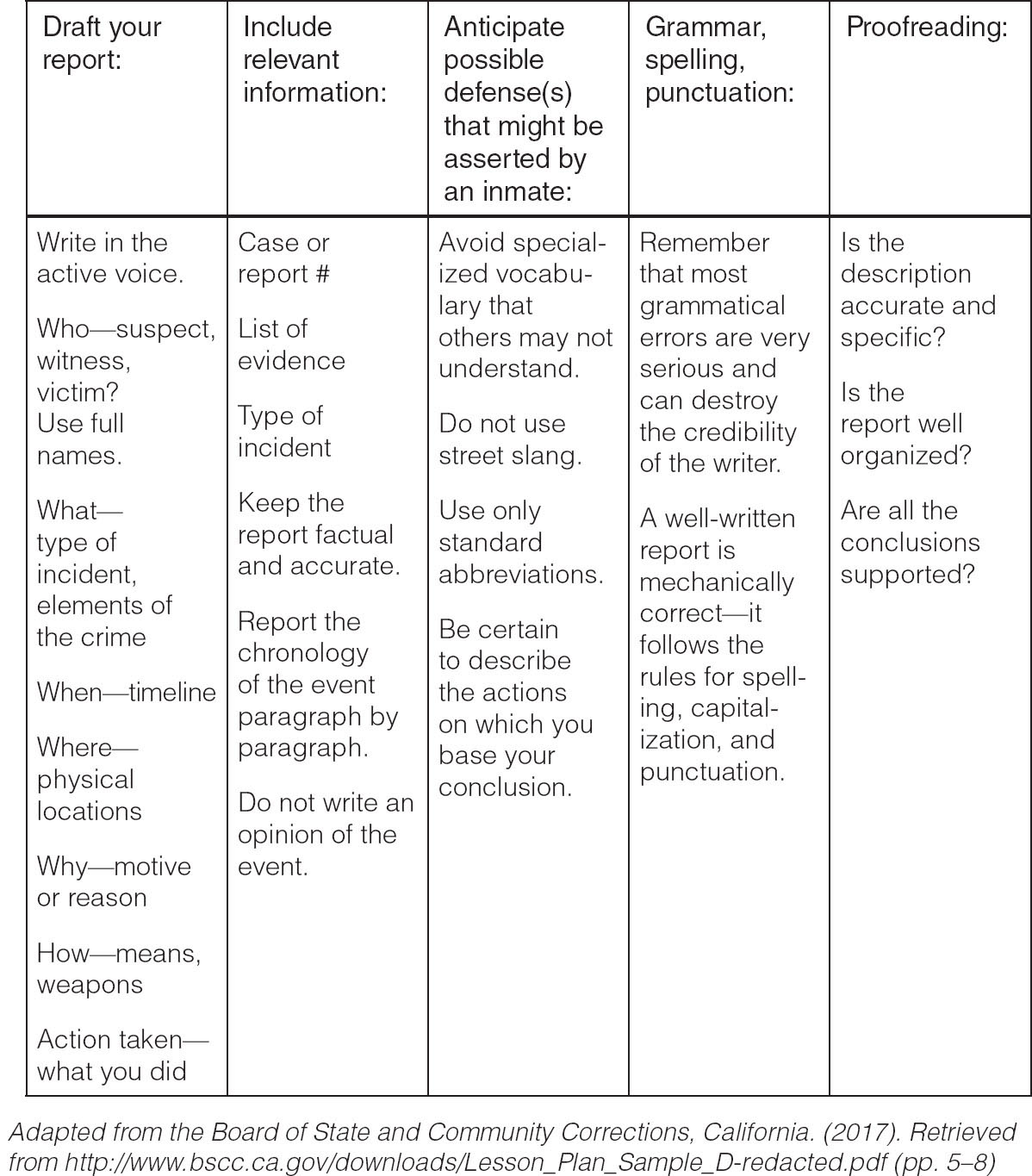

In Foundations for Critical Thinking, Paul and Elder (2009) suggested using a checklist to analyze the logic of writing. Box 6.1 lists nine key elements to be assessed.

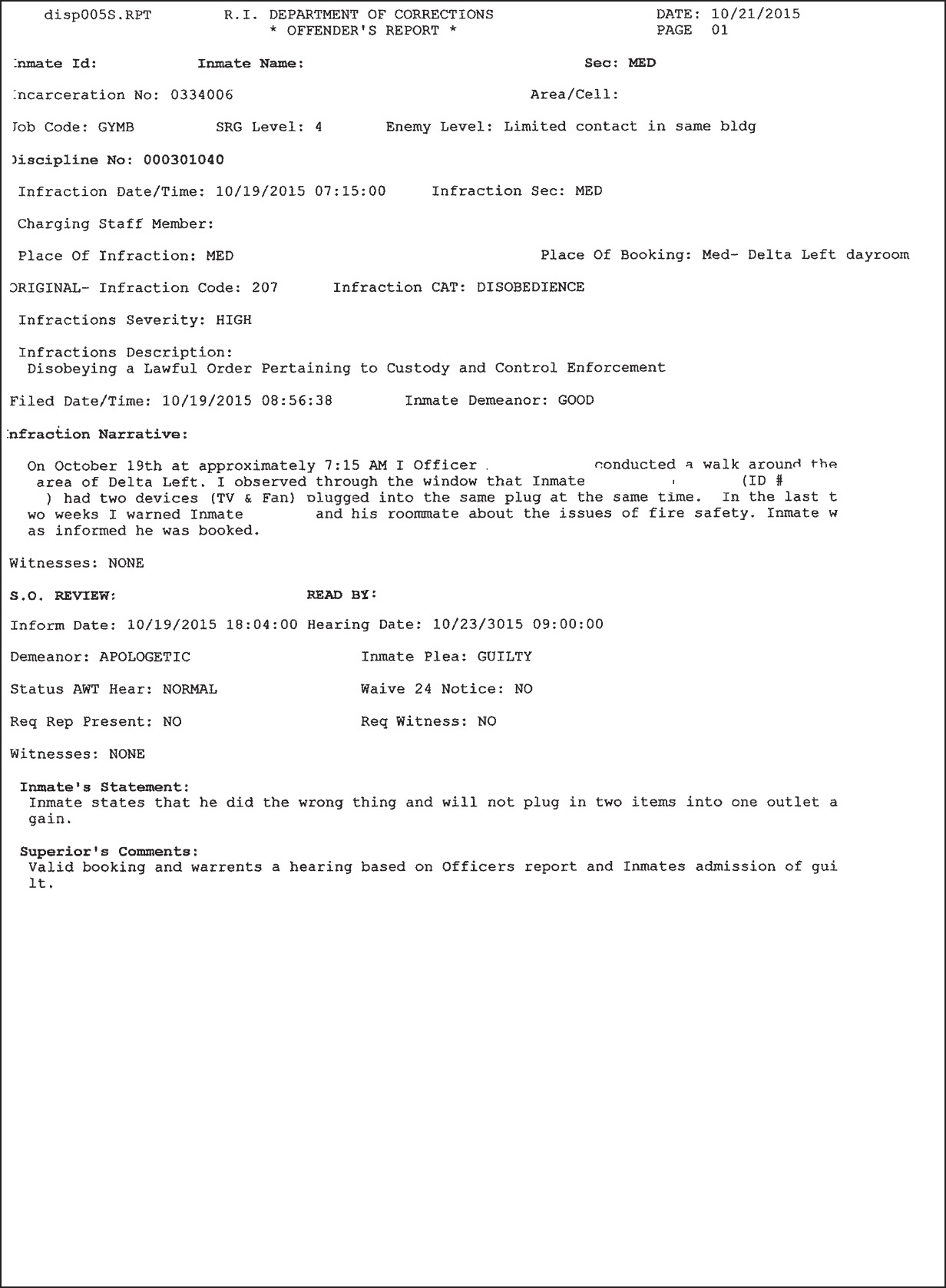

Probably the most common mini report that COs have to do involves describing an inmate’s infraction. This is called an infraction narrative. An infraction is a violation during incarceration and can range from minor, such as having too many books or magazines in a cell, to a major event, such as being aggressive toward another inmate or correctional staff. Most prison systems use a database to record these events. These databases come with a drop-down menu from which the officer selects a code that best applies.

139BOX 6.1 Report Writing Checklist for Corrections Officers

Because every incident is different, reports require written narratives in addition to standardized drop-down menus. The officer’s commanding officer and warden are likely to read the narrative. Based on what we have written, a superior may accept (validate charges) or reject (dismiss the charges) our report. On the surface, rejecting a report does not seem like a big deal, but remember that it can undermine our effectiveness on the job. If a charge didn’t stick because the report was inadequate or was not what the video camera recorded or was not what another officer at the scene reported, the larger inmate 140population may (correctly) see you as someone they can take advantage of. COs can develop a reputation with the inmate population, and it is unlikely that anyone wants to have one in which the inmates know they can commit infractions with impugnity. Needless to say, the drop-down menus can only supplement your written narrative to make an infraction charge valid and credible.

Inmate conformity to prison rules is paramount for an orderly, safe, and secure prison environment. Disciplinary offenses are typically categorized into four classes: Class A (or sometimes called 100 level) offenses are the most severe and can include hostage taking; assault with injury resulting; participating in a riot; starting a fire; throwing liquids, such as urine or feces; or making an escape or attempted escape. Class B (or sometimes called 200 level) offenses are making or possessing a weapon with intent to use it; willfully tampering with locks, fences, doors, gates, or video cameras; knowingly inhaling or using substances to become intoxicated; committing or soliciting sexual acts or masturbation; interfering with a staff member’s duties; failing to report to work or other duties; selling or misusing medications; and communicating directly or indirectly with persons or family members related to victims in a case. Class C (or sometimes called 300 level) offenses vary and can be anything from willfully inflicting harm on oneself (such as attempting suicide); offering a bribe; willfully taking another’s property without permission; and possessing stamps above the authorized limit. (Stamps are easy to hide and are often used as a prison currency.) Class D (sometimes called 400 level) codes, obviously the smallest of infractions, can include transgressions like gambling; negligently not finishing an assigned work task; possessing contraband (such as having too many books or magazines in one’s cell); and being in an unauthorized location. After a report is filed and approved, an infraction charge will go to a board hearing to determine its validity and assign a sanction.

An infraction report includes the following information:

• Inmate identity number

• Enemy level

• Job code

• Incident date and time

• Infraction code

• Staff member charging the infraction

• Infraction type

• Place of infraction

• Infraction severity (highest, high, medium, minimum)

• Witnesses

• Inmate statement

• Inmate plea

• Inmate demeanor

• Infraction narrative

The infraction narrative must be concise. Typically, we are expected to write into a text box and submit the report electronically. This means that we do not have the luxury of reviewing or revising it once we hit Submit. Our goal is to write accurately the first time, so that the infraction report passes the supervising officer’s scrutiny. An investigating lieutenant will get statements from the inmate(s) involved, and submit 141those statements into the same electronic form. Once it is approved, the infraction moves to the hearing board where the inmate may make a statement about his or her plea. Inmates may plead not guilty, guilty, or guilty with explanation. The hearing board then determines whether the infraction stands, and if yes, sanctions are imposed on the inmate.

Here is an example of a form with a narrative that was rejected by the shift command captain at the time the report was filed:

Inmate ID number: 035420X

Enemy Level: Not housed in same building

Job Code: SRG Level

Infraction Date/Time: 10/18/2015 13:35:00

Staff member charging the infraction: Lester

Infraction Code: A161

Place of Infraction: Minimum

Infraction Severity (Highest, High, Medium, Minimum): Highest (non-predatory)

Inmate Demeanor: Unknown

Witnesses: Unknown

Inmate Plea: Guilty, with an explanation

Inmate Statement: Will make statement at board

Infraction Description: Fighting (inmate on inmate) No serious injury

Infraction Narrative: “On the above date and time I Officer Lester called a Code Blue after witnessing inmate Chaves and inmate Williams fighting in room 15. After calling the Code Blue Officer Ferguson and I ordered the inmates to stop fighting. They did not want to comply. We had to break up the fight. Officer Ferguson cuffed inmate Chaves and escorted him to a holding cell. I cuffed up inmate Williams and escorted him to the nursing station for evaluation. No further incidents to report.”

When this electronic report reached the captain’s desk, she had several questions for Officer Lester. She asked that he clarify and elaborate on, “They did not want to comply,” and “We had to break up the fight.” In her opinion, these statements were not accurate, precise or clear enough. There seemed to be a gap in the logic that needed more specificity: In what way did they not comply? How were they fighting? How were the officers easily able to escort them? Who was the instigator? What was the fight about?

Breakout Writing Assignment

Imagine that you are Officer Lester and witnessed the altercation. Rewrite the aforementioned infraction narrative to include missing details. Use the checklist in Box 6.1 as an aid.

Conclusion

COs have very difficult jobs, arguably the most challenging in the justice system. Besides working in tightly structured institutions with involuntary populations, the CO must write numerous reports, often documenting situations and episodes in which 142he or she is a participant or witness. And every report may be reviewed by supervisors and supervisors’ supervisors, all the way up the organizational structure and into the legal system.

Using the example of a witness report involving the use of force, the chapter illustrates how original field notes lead to drafts and, through a process of critical thinking, to a comprehensive and competent report. We conclude with a critical thinking-based checklist for report writing, developed by Paul and Elder (2009).

References

Board of State and Community Corrections, California. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.bscc.ca.gov/downloads/Lesson_Plan_Sample_D-redacted.pdf (pp. 5–8)

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2009). The miniature guide to critical thinking, concepts and tools: The foundations of critical thinking (6th ed.). Dillon Beach, CA: Foundations of Critical Thinking Press.

ToersBijns, C. (2012). Report writing for correctional officers. Retrieved from http://www.corrections.com/news/article/30175-report-writing-for-correctional-officers

143Field Documents

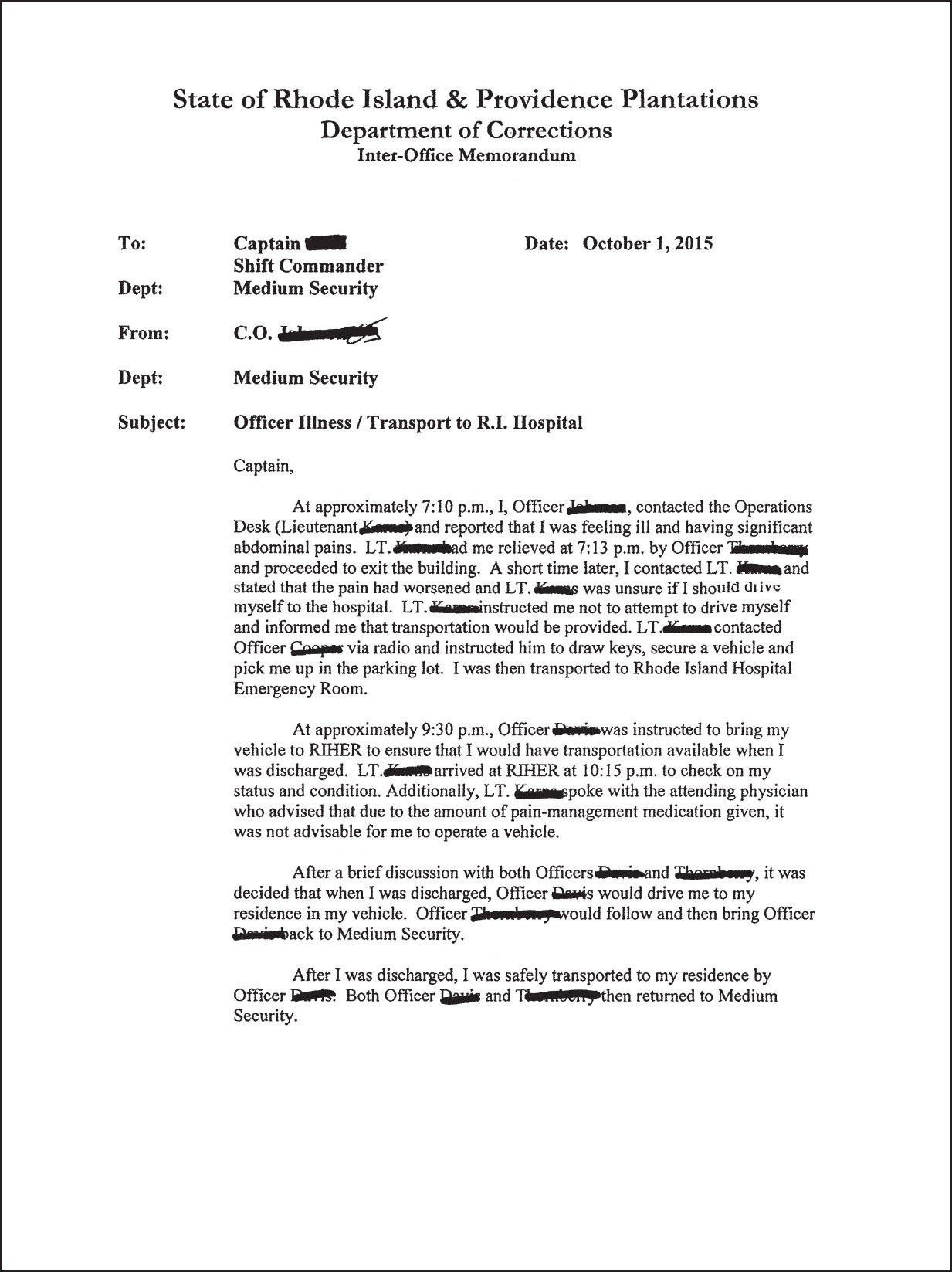

Following are some actual documents, edited to protect confidentiality.

144

145

146