5

English Experiences

SIR JOHN CHAMBERLAIN was an independently wealthy gentleman who spent his time writing the news to correspondents all over Europe, and he reported the Treasurer’s arrival in June 1616: “Sir Thomas Dale is arrived from Virginia and brought with him some ten or twelve old and young of that country, among whom the most remarkable person is Poca-huntas (daughter of Powhatan a king or cacique of that countrie) married to one Rolfe an English man.” Chamberlain highlighted the exotic nature of the visitors by using the term “cacique,” meaning ruler, which appeared in reports from the Spanish colonies.1

The Virginia Company’s strategy was working. Pocahontas and her company were already attracting favorable attention. No one mentioned what she and her party thought of London and its crowds.2

The Virginia Company was determined to present Pocahontas properly. Native men who were brought to London were displayed wearing their traditional garb, because they were seen as exotic specimens. Pocahontas was now the Lady Rebecca Rolfe, and her clothing needed to show her status as a Christian gentlewoman. Her huge challenge was getting used to the clothes she had to wear.

For a woman used to the relative freedom of her own native clothing, putting on her new English lady clothes was a horrible shock. Ladies had an experienced maid to do all the lacing, tying, and hooking involved in these complicated clothes. First you put on a smock, a long shirt-like garment made of linen. Over that, your maid tied on a pair of bodies, what we would call a bodice or corset, that the maid laced together down your front or back. Bodies had channels sewn into them that were filled with whalebone or bundles of reeds, called bents, in the channels that ran up and down. After it was all laced together, a piece of horn or wood, called a busk, was pushed down the front to stiffen it.

Then a petticoat was tied to the bodice, and over that, the maid placed a roll of cloth, called a bumroll, that went around your waist so your skirt would stick out all around you. Pocahontas wore a “high-bodied” gown that had buttons at the top and a skirt, which is what the English called the tabs that hung from the waist. The wings that extended out from the shoulders covered the line where the sleeves joined the gown. At the top, your maid tied on a large starched collar that was supported by a network of wires. So your clothes poked and scratched you throughout the day, not to mention how heavy it all was. No woman could afford to slouch ever. Add to that the discomfort of wearing hard-soled shoes, maybe even with small high heels.3

One advantage of all this elaborate clothing was that it covered up Pocahontas’s tattoos. George Percy wrote that women in Virginia “pounce and race their bodies, legs, thighs, arms and faces with a sharp Iron, which makes a stamp in curious knots, and draws the proportion of Fowls, Fish, or Beasts, then with paintings of sundry lively colors, they rub it into the stamp which will never be taken away, because it is dried into the flesh.” Only tattoos on her face would have been visible to curious Londoners, and no one mentioned seeing them.4

Pocahontas also had to get used to wearing her hair up. Married English women wore their hair pinned into coils on their heads. They covered it with a linen cap, referred to as a coif, and then a hat with a tall crown and brim over the cap.

English food was also very strange. Having beer or wine with every meal was disorienting to people used to fresh water, and they began the day with an unaccustomed wooziness. The variety of foods was much more limited than the Virginians were used to, and their preparation was definitely unappetizing.

In the absence of refrigeration, there were only three ways to preserve food: drying in salt, boiling in vinegar, or making a jam with sugar. Salt and vinegar were used to preserve meat and fish. So except in the summer months, Pocahontas’s party ate a lot of salted or pickled food, but they would have had roast beef and roasted or boiled chicken as well as salt cod and beef. Their vegetables in winter were mainly roots: carrots, parsnips, and turnips.5

Apples and pears could be kept in cool cellars, and plums could be dried into prunes; but other fruits were only available preserved in copious amounts of sugar. England did not yet have its own sources of sugar from Caribbean plantations, and imported sugar was very expensive; so most people had little fruit in the winter. Some medical experts claimed that fruits were dangerous to eat anyway, so lack of them in the winter was no problem.

As you progressed down the income and status scale, bread became a larger and larger part of your diet. Everyone ate bread and butter for breakfast, and the richer you were, the whiter the bread. In England as in Virginia, these years saw many poor harvests and consequent food shortages. There was a harvest failure once every seven years, according to one source. In the worst times, the poor ate bread made of acorns rather than wheat, oats, or rye. Acorn bread, if the visiting Powhatans saw it, would have been familiar to them because they ate it at home. A character in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar refers to the “stinking breath” of the common people, which was a result of their poor diet. Low consumption of fruits and vegetables also contributed to chronic low-level scurvy, caused by vitamin C deficiency.6

London was a rapidly growing city: from fifty thousand inhabitants in 1500, its population had increased to two hundred thousand by 1600.7 When Pocahontas and her entourage were in London, they stayed at the Belle Sauvage Inn on Ludgate Hill, near St. Paul’s Cathedral. It was originally called the Bell Inn, and an early owner, named Savage, added his own name. So it is pure coincidence that the inn name seems to echo the way Londoners saw Pocahontas. The inn’s courtyard was a playhouse, and the Belle Sauvage was a place of constant traffic of Londoners going in and out.8 The government made persistent efforts to stop performances of plays in inns, but it is unclear how effective the ban actually was.

In Ben Jonson’s play The Staple of News, a character says, “I have known a Princess, and a great one, come forth from a tavern.” When challenged, the character retorts, “the blessed Pocahontas (as the Historian calls her and great Kings Daughter of Virginia) hath been in womb of a tavern.” The historian referred to here was Capt. John Smith.9

The Virginians were thrust into a bustling part of London. The cathedral bell would have kept them in time with the passing hours, and they would have seen London’s busy and varied population. The courtyard of St. Paul’s Cathedral was not the quiet place of contemplation we might associate with a churchyard. Rather, it was the center of the English publishing industry. Printers and more than two hundred booksellers crowded the area, and their patrons created a constant flow of people. That is where you went to hear the news and all the latest gossip.10

St. Paul’s was in the western-most part of the old City of London, enclosed in the wall originally built by the Romans. Ludgate was one of seven gates in the wall, and because it was adjacent to the cathedral, it had a singularly important role. To the west was Westminster, then a separate city and the seat of government, so “Ludgate was the threshold between St. Paul’s and Westminster, between spiritual and earthly power.” Coronation processions passed through Ludgate on their way to Westminster, and the gate was closed on the death of Queen Elizabeth. And Ludgate also served as a debtors’ prison to separate debtors from common criminals. Ludgate Hill became Fleet Street as it moved down the hill, and Fleet Street eventually turned into the Strand.11

Just outside the gates of St. Paul’s was a huge market where farmers brought vegetables for sale. In addition to locally grown produce, London also imported onions, carrots, and cabbages from the Netherlands. This market grew so big that it was moved to Covent Garden, newly rebuilt by Inigo Jones, a few years later.12

The Blackfriars Theatre was just a few blocks away. Shakespeare had been a member of the King’s Men, the company that played there, but he died in April 1616, just two months before Pocahontas’s arrival. His Tempest, with its echoes of American experiences, was performed at the Blackfriars. The nearby Mermaid Tavern saw regular gatherings of poets and playwrights, including Ben Jonson, John Donne, and Inigo Jones. Cheapside, center of London’s commerce and home of its wealthiest goldsmiths, runs along the northeast side of St. Paul’s. This is another misleading name; rather than being a place for the thrifty shopper, its name comes from an old English word, ceap, that meant bargaining or a place where bargaining took place.13

Nineteenth-century engraving of the Belle Sauvage Inn from Henry C. Shelley, Inns and Taverns of Old London (Boston: L. C. Page, 1909).

Prisons were also near neighbors. The Fleet, where political prisoners were housed, and the large Newgate Prison were both close by. Bridewell, where the poor were kept out of the way, was also right there. Poor children from Bridewell were later sent to Virginia as servants. On the other side of St. Paul’s was Bethlehem Hospital for the insane, whose name was compressed into “Bedlam.”

The Fleet River, for which the prison was named, ran nearby, and the Virginians were not far from the Thames, with its constant traffic of boats and ferries. London had no sanitation system, so all the by-products of industry and the waste of daily life ultimately ended up in the rivers. As they compared the crowded, noisy, and dirty city to their own Werowocomoco, the Virginians had a lot to think about.14

Prince Henry, the golden youth for whom the Henrico settlement in Virginia was named, had died in 1612, not long after his namesake town was settled. Henry was very athletic, and rumor had it that he had insisted on swimming in the foul Thames, where he caught his fatal illness. Queen Anne, in her extreme distress, had sent to Sir Walter Ralegh to make a “cordial” of the medicines he had brought from Guiana in the 1590s. Ralegh sent his balsam of Guiana, and Henry briefly seemed better.15 He was eighteen years old when he died, and his younger brother, Charles. now became the heir apparent.

Pocahontas engraving, by Simon van der Passe, 1616, National Portrait Gallery (Accession Number: NPG.77.43).

Pocahontas’s London. Designed by Scott Walker from The Map of Early Modern London, edited by Janelle Jenstad. Map derived from the Agas Map, produced in ca. 1633, depicting the City of London in the 1560s.

The Virginia Company, insisting that it was bringing new royalty to England, rushed an engraved portrait of Pocahontas into print. Rather than having her portrait painted, something that would have been seen by a very few, the company chose to have a large number of engravings created for wide distribution. Inexpensive engravings were the social media of the day, and her image was seen by people of all classes.

Other Natives from North America had been in England, and people had flocked to see their strange dress and manners. As Shakespeare’s Tempest testified, people wanted to experience the exotic.16 Pocahontas, on the other hand, was presented as the ultimate English lady. What mattered was that she was the daughter of an emperor and a Christian gentlewoman married to an English man. Her portrait showed her in the most expensive and elaborate dress. Her hat was of felt made from beaver fur that had been bleached white, an expensive process that only the wealthiest could afford. She wore an elaborate brocade gown with a wide starched lace collar, drop pearl earrings, and a fan of three feathers. No one could doubt that she was an important personage, someone to be looked up to and admired.

Immediately beneath Pocahontas’s figure in the engraving, it says that she is in her twenty-first year, 1616. Around her image is a ribbon of text that says in Latin, “Matoaka als Rebecca Filia Potentiss: Prince: Powhatani Imp: Virginia.” Below the portrait is the translation, “Matoaka als Rebecka daughter to the Mighty Prince Powhatan Emperour of Attanoughkomouck als Virginia, converted and baptized in the Christian faith, and wife to the worthy Mr. John Rolfe.” “Als” here means something like “aka” or “alias.” Attanoughkomouck was one of the names for Powhatan’s territory that the English had learned. The more commonly used one was Tsenacommaca.

One of the most remarkable things about the portrait is that the name Pocahontas does not appear anywhere on it. This shows how closely the printer was watching the emerging story. Samuel Purchas, the man who made a profession of collecting and publishing travelers’ accounts, wrote that the leading intellectuals in London seized the chance to learn more about Virginia Algonquian religion. Sir Theodore Goulston, an important London physician and scholar and Virginia Company member, held salons several evenings at his home, where Uttamattomakin, the Powhatans’ chief priest and Pocahontas’s brother-in-law, talked with these learned men about his people’s religious beliefs and practices. Henry Spelman, identified by Purchas as “Sir Thos. Dale’s man,” acted as interpreter for these meetings. Uttamattomakin revealed that Pocahontas’s real name had been concealed from the English because of fears they could harm her if they knew her name. Pocahontas was a nickname they had been told to use to protect her. Now that she was baptized with the name Rebecca, her real name, Matoaka, could be known. Alexander Whitaker had written in his letter of 1614, published in Ralph Hamor’s True Discourse in 1615, that after her baptism, he knew that her name was Matoa.17

Over the evenings of meetings, Uttamattomakin, according to Purchas, sang and danced “his diabolical measures,” and he was very happy to answer questions and to describe his people’s beliefs fully. The one thing he warned his hosts against was trying to convert him. Purchas wrote that he was “very zealous in his superstition, and will hear no persuasions to the truth.” Uttamattomakin described how priests were able to make the deity Okeus appear among them when they gathered in a secret place and performed the rituals. He actually said the secret words that would cause Okeus to appear, but Henry was unable to translate them. Uttamattomakin said that Okeus was a “personable Virginian” in his appearance and had a long lock of hair on the left side reaching down almost to his foot. Uttamattomakin maintained that it was in imitation of their God that Virginia Algonquian men wore their hair this way. Purchas was scandalized that the lovelock now so fashionable among London dandies was actually an imitation of a deity that he considered to be the Devil.18

Many of the scholars and intellectuals gathered at Goulston’s salon had been associated with the famous English mathematician and scientist John Dee. Dee died in 1609, so he was not present; but he certainly came to mind as they watched Uttamattomakin’s rituals. Dee was known all over Europe for his learning, and Queen Elizabeth consulted him many times. Elizabeth summoned Dee when a very bright comet appeared in the night sky in 1577, and they spent three whole days discussing its significance. Some people, who were suspicious of his activities, called him the “Queen’s Conjuror.”

Dr. Dee was like Uttamattomakin in that he “conversed” with angels in person, including the archangels Gabriel and Michael, and received instructions from them. Just as Uttamattomakin used special words to call Okeus, Dee summoned the angels using special prayers. He used three crystal stones to concentrate the rays of light in which the angels appeared, and one of the crystals had been left for him by the angels outside his study window. He set up his crystals and their table according to the instructions the angels gave him. He believed that the angels were bringing him knowledge direct from God and that, using that knowledge, he and other scientists could begin to restore the earth to the way it was at the first creation. Queen Elizabeth actually came to his house to see the crystals for herself, and some said that Dee was the model for the magician Prospero in Shakespeare’s Tempest.

The revelation of the American continents, previously unknown to Europeans, was one indication that God was encouraging the creation of new knowledge. Studying the newly revealed people, plants, and animals was already contributing to greater understanding, and Dee, who was the first to use the term “British Empire,” was deeply interested in America. He wrote a book, now lost, on ways to convert American Natives, and he was an adviser to several voyages to the far north searching for the Northwest Passage that would allow ships to cross through to the Pacific Ocean.

As a reward for all Dee’s efforts, Queen Elizabeth issued a patent that gave him, on paper, ownership of most of Canada. One of his last acts was to write a report on the blazing star, Halley’s comet, seen by the first supply fleet carrying Thomas Savage, and he sent the report to Thomas Harriot. Both men were deeply involved in the study of optics or light, partly because light, in which the angels appeared to Dee, was God’s first creation.19

As scholars sought understanding of this previously unknown culture and its deepest meanings, English elites honored Pocahontas as visiting royalty, and John Rolfe faded to the background. Samuel Purchas described how she was honored: “I was present when my Honorable and Reverend Patron, Lord Bishop of London, Dr. King entertained her with festival state and pomp beyond what I have seen in his hospitality to other ladies.”20

Pocahontas and Uttamattomakin were “graciously” received at court, where they were in the audience for The Vision of Delight, a masque written by Ben Jonson, staged by Inigo Jones, and performed on Twelfth Night (January 6, 1617). It was part of the court’s Christmas celebrations, and the two Virginians were “well placed” among the spectators; “well placed” meant near the royal family.21 Being near the king meant that Pocahontas and Uttamattomakin had the ideal view of the scene. People seated on the sides had to crane their necks to see.

Masques presented allegorical characters that represented good and bad forces. The Vision of Delight, which was set at night and in midwinter, opened on a life-size streetscape, with a “fair building.” Delight entered first, followed by Grace, Love, Harmony, Revel, Sport, Laughter, and Wonder, and they sang of the pleasures of spring. Then suddenly some antimasquers entered. These were the bad elements. A she-monster gave birth on stage to six “burratines,” grotesque characters from Italian comedy. In addition, there were six outlandish older men, called pantaloons, who danced with the burratines.22

The speeches were shot through with double meanings and sly hints of lechery and gluttony. Pocahontas and Uttamattomakin may not have caught the allusions from English popular culture, but they certainly took in the strange and wonderful events unfolding before them. Night rose in a “chariot bespangled with stars” and trailing a train of flames. The moon also hovered over the scene. Soon clouds covered the skyscape, and Fantasy broke forth with a long speech about all the kinds of dreams he could provide. The wild antimasquers broke onto the stage again.

Then suddenly, with a burst of loud music, the scene changed to a spring setting. Green countryside replaced the London street, and lambs and flowers dotted the landscape of green plants and flowing rivers. The masquers danced, and they and the audience experienced a waking dream of the spring to come. The character Wonder asked how this transformation could have come about. The air was suddenly mild, fields had their “coats,” and winter was banished underground. Wonder posed the question, “Whose power is this? What God?” Then Fantasy stepped forward and gestured toward King James, saying, “Behold a King, Whose presence maketh this perpetual Spring.”

Masques presented order and disorder as opposing forces vying for control. At the conclusion, the king always restored proper order. In this particular masque, the dancers were presented as figures in dreams, and the audience was invited to see themselves as dreamers also. The first lines of the masque were sung, so Pocahontas and Uttamattomakin could see real connections with worship in their own community, which was conducted in song. Did Pocahontas think back to the dance performance with which she and her friends had welcomed Capt. John Smith? Smith called it a “Virginia Masque,” and it shared many elements with this English one.

Uttamattomakin and Pocahontas would have understood and responded to the dreaming dancers. Dancing could produce a dream state, and, in their worship, dancing allowed them to connect with the world of spirits. Dreams were powerful for them, and Uttamattomakin, as a priest, was the carrier and interpreter of dreams because he was able to move between the human and spirit worlds. English people could also experience dreams as important links to the supernatural. John Rolfe had written in his letter explaining why he wanted to marry Pocahontas that God came to him in his sleep urging him to spend all his effort to make her a Christian. The visitors from Virginia found powerful and familiar themes in The Vision of Delight.

Masques were extreme costly and lavish productions, and they often had only one performance. Sets were large and intricate, and the masquers wore costumes in the most expensive fabrics. They were accompanied by large numbers of professional musicians. The Vision of Delight required ten French musicians. Because masques were meant to show off the importance of the king and his courtiers, the expense was part of the show. The Vision of Delight did have a second performance later in the month. But two performances were little enough for the £1,500 or so (over £100,000 in modern currency) that it was said to have cost. The caustic letter writer John Chamberlain wrote, “I have heard no great speech nor commendation on the masque neither before nor since.”23

Uttamattomakin was not impressed either. When he met with Capt. John Smith toward the end of his stay in England, Smith reported that Uttamattamokin said Powhatan “did bid him to find me out, to show him our God, the King, Queen, and Prince, I so much had told them of.” Smith did his best to describe the Christian God, and he told Uttamattomakin that he had seen the king for himself. Uttamattomakin refused to believe that the unimpressive man he had met was actually the powerful monarch of whom he had heard such reports.24

English observers always described Powhatan as a man of immense dignity, and as Henry said, he did not dress differently from other men because he was set apart by the great honor his people showed him. English royalty gained respect in the opposite way, through lavish display. King James’s coronation robe cost £2,172, and that for his queen, Anne, was £1,996, the equivalent of hundreds of thousands of pounds today.25

James I was awkward, not dignified, in his self-presentation. Sir John Oglander, a staunch supporter of the monarchy, began his “Note on King James” with the statement, “King James the First of England was the most cowardly man that ever I knew.” Oglander did praise his learning and wisdom and his concern for his people’s welfare. Oglander also recorded that James loved men more than women, “loving them beyond the love of men to women,” and singled out the royal favorite, the Duke of Buckingham. James hated the fact that ordinary people thought they had a right to see their king. When the public pressed around him, his courtiers told him they “came out of love to see him,” and his reply was, “God’s wounds! I will pull down my breeches and they shall also see my arse!”26

Capt. John Smith described the very formal way that Powhatan washed and dried his hands before and after eating, but James I was said to have hands as soft as silk because he never washed them. The Duke of Buckingham once closed a letter to the king saying, “And so I kiss your dirty hands.”27

When Smith finally convinced Uttamattomakin “by circumstances” that the man he had met really was the king, Uttamattomakin remarked on James’s stinginess, a serious defect in a man who wanted to be thought great. Powhatan earned the respect of his subjects partly because he distributed everything he had to his people, but as the fabulously expensive masque showed, James I accumulated wealth for himself and his favorites. Uttamattomakin reminded Smith that he had given Powhatan a white dog, which Powhatan kept with him always, “but your King gave me nothing, and I am better than your white Dog.” His report when he returned to Virginia must have been really interesting.28

Other Virginians were in London then. Squanto, the man who later became famous as the Pilgrims’ adviser and interpreter in New England, was in London at the same time as Pocahontas. The English applied the name “Virginia” to the entire east coast of North America, so Squanto, a Patuxet from New England, was also a Virginian in English eyes. Several different people wrote his story, and each telling was slightly different; so our understanding of what had happened to him is a bit murky. Patuxet was on the Massachusetts coast near where Cape Cod begins, and many ships ranged those waters. The northern New England and Newfoundland coasts attracted huge transatlantic attention because the rich fishing grounds provided badly needed protein for Europe’s burgeoning population. The French explorer Samuel de Champlain had traveled around Massachusetts Bay early in the seventeenth century, and his map showed the site of Squanto’s village.

Capt. John Smith, after his departure from Jamestown, felt that his contributions had been undervalued, so he turned his attention to New England, which he argued was a better place for English people to prosper. He actually invented the name “New England” as a promotional tool. He wanted his readers to see that the more northern sections of North America’s east coast were better suited to English bodies than hot Virginia was, and he published his first book promoting the region in 1616, when the Virginia Company was working hard to garner support for its colony.29

Smith had gotten backing for two ships to scope out possibilities in 1614. They planned to hunt for whales and to look for mines with valuable ore. If neither worked out, they would try to get fish and furs. They did manage to get some fish, and Smith’s ship returned to England to sell some of their take.

The other ship, captained by Thomas Hunt, stayed behind, supposedly to salt and dry the rest of their fish for sale in Spain. But Hunt actually had a very different plan. This “worthless fellow” lured twenty-four young Native men onto his ship and then took “these poor innocent creatures” prisoner. Squanto was one of the twenty-four. Hunt was “more savagelike than they,” and his scheme was to sell his captives into slavery in Málaga in Spain. But Hunt’s plan was thwarted when Spanish authorities intervened, and his captives were turned over to Roman Catholic priests to be instructed in the Christian religion.30

Málaga is on Spain’s Mediterranean coast, so it is surprising to learn that there was a small community of English merchants there. The merchants’ ships brought fish from Newfoundland, which was especially important to Spain’s Roman Catholic population for their fish days. In return, the ships carried wine and raisins back to England. This was a mutually beneficial connection, and the authorities did not want rogue traders like Hunt messing it up. The presence of the English merchants in Málaga solves another mystery about Squanto’s life: how he got to England. He traveled on one of the merchants’ ships with the all-important wine shipment.

One thing about Squanto’s life that we do know for sure is that he was living in England in 1616 and 1617 when Pocahontas and Henry Spelman were there. He stayed with John Slany, treasurer of the Newfoundland Company, at his house on Cornhill, a short distance from Ludgate, where Pocahontas and her train were lodged.31 At that time, plans to colonize in Newfoundland were not going well, largely because the fishermen went there in the spring and returned in the fall and did not need an expensive permanent residence. And after Sagadahoc in Maine had been abandoned, there were no English colonies in New England. So the Newfoundland Company had no incentive to trumpet Squanto’s presence with the kind of publicity and show that advertised Pocahontas and her entourage.32

But given the few short blocks that separated their living quarters, it is tempting to imagine that Pocahontas or Uttamattomakin met Squanto.33 The Powhatans and the Patuxets spoke languages of the Algonquian language family, so they might have been able to communicate on some level, just as Spanish and Italian speakers can. Squanto’s experience recalled Paquiquineo, the Paspahegh man tutored in Christianity by priests in Spain before his return to the Chesapeake, and Uttamattomakin would have valued better understanding of those experiences.

The Newfoundland Company may not have been interested in fundraising in 1616, but two huge campaigns competed for the public interest that year, one by the Virginia Company and the other for a Guiana venture by Sir Walter Ralegh.

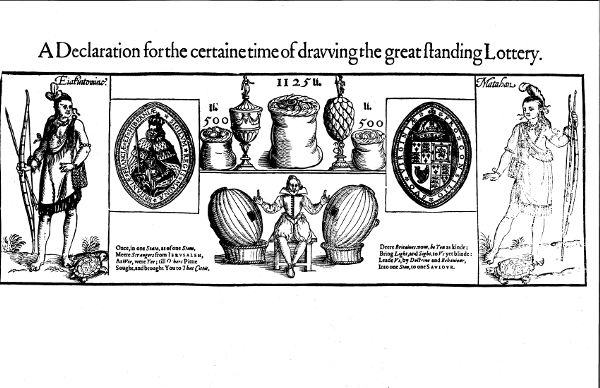

The Virginia Company tweaked a project it had had in the works since 1612, a lottery scheme to bring in revenue. The company’s 1612 charter had authorized a lottery; it was held in London, and the company tried to create a stir around it. The Virginia Company set up its lottery house at the west end of St. Paul’s churchyard to catch all those who were looking for the latest news. Agents created a broadside advertising the 1612 lottery, and the new Spanish ambassador, Diego Sarmiento de Acuña, Count of Gondomar, was interested enough to secure one and send it to Spain. It is now in the archives in Simanca as the sole surviving copy. But this lottery and the ones that followed were disappointing. There was a large time gap between a person’s buying a ticket and the announcement of the prizewinners, sometimes many months or even years, and there had also been charges of corruption among the managers.34

In 1615, the company decided to hold another “Great Standing Lottery,” with high ticket prices and lavish prizes promised. For this lottery, the company commissioned a ballad, “London’s Lotterie,” to the tune of “Lusty Gallant.”35 And in February 1616, just a few months before Pocahontas’s arrival, the Virginia Company published a prospectus for its new and improved lottery that carried pictures of two men: Eiakintomino and Matahan. Eiakintomino was displayed in St. James’s Park, and a Dutch visitor did a watercolor painting of him that was used in this prospectus.36 Both men are holding bows, and each has a turtle by his feet. The poster, which also carried an image of King James I and the Virginia Company seal, advertised the lottery and the cash prizes it offered, illustrated by bags of money. It showed a man sitting between two huge bins, from which the winning tickets would be drawn. Patriotism had not worked as well as the Virginia Company hoped in attracting money, so it thought appealing to people’s greed and love of gambling would be better. It all sounded perfect, but this one still failed to sell enough tickets.

So, in 1616, the Virginia Company again revamped its plan. The previous lotteries had been in London and were called “standing lotteries,” but now company officials created what they called a “running lottery.” Company agents went to cities and towns all over England and proposed holding a lottery in them. The town would benefit, and part of the proceeds would go to charity. Delays in announcing winners had discouraged prospective ticket holders, but the running lotteries offered instant results and real rewards. The running lotteries created a festive atmosphere, and they brought Virginia to popular attention all over the country. They also brought in money.37

Meanwhile, Sir Walter Ralegh was soliciting funding for a venture to Guiana on the Caribbean coast of South America. He had been freed from a very long imprisonment in the Tower of London in March of that year in order to carry out his plan. Ralegh had been the backer (and owner) of the ill-fated Roanoke colonies in the mid-1580s. Although he never went to Roanoke, he did lead an expedition to Guiana in 1595, and he returned convinced that the fabled golden city of El Dorado was there, as he argued in The Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana, with a Relation of the Great and Golden City of Manoa (Which the Spaniards Call El Dorado) (1596).

When James I came to the throne after Queen Elizabeth’s death in 1603, he believed that Ralegh had conspired to block him from becoming king, and he committed Sir Walter to prison on a suspended sentence of death. From 1603 on, Ralegh campaigned to be allowed to return to Guiana in search of the wealth he was certain was there, and his appeal was finally effective in 1616. His permit stipulated that there would be no violent clashes with the Spanish. King James was not going to rekindle the war with Spain from Queen Elizabeth’s time through some hotheaded actions over there.

During 1616 and the first part of 1617, Guiana and Virginia dueled for a place in the public imagination. Ralegh gathered £30,000, a sum close to what the Virginia Company had raised over the previous decade, and his expedition set sail in June 1617. His ship was aptly named Destiny.38

Ralegh had left two English boys in Guiana in 1595, but neither was present in 1617. Ralegh had promised to return in 1596, but as often happened with this kind of plan, events in England prevented it. Francis Sparrey had been captured by the Spanish and taken into prison in Madrid, where he became Francisco Espari. Hugh Goodwin had been killed by tigers, according to Spanish reports.39 Thomas Savage and Henry Spelman would have been abandoned in the same way if Lord de la Warr had not arrived in the nick of time when the Jamestown colonists gave up and headed for home in 1610.

Ralegh’s new expedition did not find the hoped-for gold, and some of the men attacked a Spanish fort while they were in Guiana, violating the king’s instructions. Ralegh’s 1603 death sentence was carried out after his return in 1618, and his execution made many people unhappy. Chamberlain wrote three weeks later, “We are so full still of Sir Walter Ralegh, that almost every day brings forth . . . ballads” and other “stuff.”40

The search for American gold had once again ended in tragedy with Ralegh’s execution, but the Virginia Company also faced negative publicity. The Virginia Company was certain that tobacco was going to be the gold to finance its colony, but tobacco still seemed to be a problematic product. Ideally, the colony would have produced something essential to life, such as the medicines that the apothecaries looked for, and enhanced England’s economy that way. Tobacco was clearly not essential, and many people thought it was corrupting.

Pocahontas’s people used tobacco for ceremonial purposes and to sustain themselves when on long journeys, but in Europe, tobacco was swiftly becoming a big exotic fad. Tobacco had been coming into England from the Spanish colonies for decades, but it was expensive and only for the ultra rich. Soon, with tobacco cultivation spreading over the land in the Chesapeake, it was a product almost everyone could buy. Drinking tobacco smoke, as they put it, was Europe’s first huge consumer craze.

Some people argued that tobacco was actually beneficial to health, as the exhalation of hot and dry smoke would help eliminate excessive cold and moist humors from the body. Thomas Harriot, in his book on the people and land of the Carolina coast, had praised tobacco, saying, “it purgeth superfluous phlegm and other gross humors, openeth all the pores and passages of the body, . . . whereby their bodies are notably preserved in health.” He also testified, “we ourselves during the time we were there used to suck it after their manner, as also since our return, & have found many rare and wonderful experiments of the virtues thereof.” To detail all tobacco’s healthful qualities, he wrote, would require a whole book in itself.41

Others, including King James, considered smoking both filthy and dangerous.42 In 1604, long before there was an established tobacco industry in English-claimed territory, James had written A Counterblast to Tobacco. In 1607, as Jamestown was first planted, Cambridge University authorities forbade students “taking tobacco,” which they associated with excessive drinking.43

When Pocahontas and her party were actually in London, Thomas Deacon published, with the king’s official stamp of approval, Tobacco Tortured; or, The Filthy Fume of Tobacco Refined: Shewing All Sorts of Subjects, That the Inward Taking Tobacco Fumes, Is Very Pernicious unto Their Bodies; Too Too Profluvious for Many of Their Purses; and Most Pestiferous to the Public State. Deacon linked the derangement caused by tobacco smoking to all kinds of public disorder, up to and including the “Gunpowder Treason” of 1605. Another author claimed that the imprisoned Gunpowder Plot traitors “took tobacco out of measure” and were so drugged that they seemed to have no fear or feelings as they faced their terrible executions.44 Capt. John Underhill in New England later reportedly said that he had actually had a religious experience uniting him with God while “taking a pipe of Tobacco.”45 With its consciousness-altering properties, tobacco continued to be problematic, especially as it was considered an American, and therefore alien, substance.

Everyone was soon able to buy tobacco because, as the Virginia crop grew, the price continued to drop, making it available to the masses. In 1592, the Earl of Northumberland, George Percy’s older brother, paid four pounds for a pound of tobacco, and John Aubrey, writing later in the seventeenth century, remembered his grandfather saying that a pound of tobacco had cost a pound of silver. In his grandfather’s day, the gentry had pipes made of silver; “the ordinary sort made use of a walnutshell and a straw.” By 1618, a pound of tobacco cost two or three shillings (there were twenty shillings in a pound). And a decade later, the price had dropped to a few pennies (there were twelve pence in each shilling). A satirical book called The Honesty of Our Age claimed that a survey found seven thousand stores and taverns selling tobacco in London and its suburbs at the time Pocahontas was there. And the Virginia colony benefited immensely from it. John Pory wrote in 1619, “All our riches for the present do consist in Tobacco.”46

Meanwhile, the Virginia Company was making plans to move Pocahontas and her party out of London. They may have made one short trip to Norfolk, to John Rolfe’s home in the village of Heacham; local tradition there maintains that he brought Pocahontas and their son to visit his family. Pocahontas would have welcomed the chance to see some of the landscape away from the dirt and noise of London, especially after seeing the countryside portrayed in The Vision of Delight.

Image of tobacco shop window, 1617. Richard Braithwaite, The Smoaking Age. Courtesy of the British Library Imaging Services.

Henry Spelman’s home was also in Norfolk, and he presumably met with some of his family during his time in England and persuaded his fifteen-year-old brother, Thomas, to go to Virginia. Thomas, who was identified in the records as a gentleman, paid his own way in 1616 and therefore was eligible for a land grant. Maybe the three pounds he had received in the will of his great-uncle Francis Saunders early in 1614 had helped pay the cost of an ocean crossing. In 1625, the court records show that he left a boy with a planter named Luke Eaden in exchange for a barrel of corn; he intended to redeem the boy when he was able to repay the debt.47

Pocahontas and her party did move away from London to Brentford, a suburb to the west of the city next to where the royal botanical gardens at Kew would be founded in the next century. The Virginia Company decided that a healthier and cheaper environment would be better for the visitors, and George Percy helped arrange the move. Brentford was the site of Syon House, the London home of the Percy family. George’s older brother Henry, the present Earl of Northumberland, was confined in the Tower of London on suspicion of involvement in the Gunpowder Plot, but George was living in Brentford.

Although the sources do not mention their meeting, another man with American experience was also present. Thomas Harriot had his own cottage at Syon House, where he carried on his scientific work.48 The Earl of Northumberland’s interest in science had earned him the nickname of the Wizard Earl, and Harriot, who had become one of the leading practitioners of the new science of the day, worked with him, bringing him materials and expertise for his experiments in the Tower.49

Harriot and the Virginia visitors probably met many times while they were all in Brentford. Harriot himself had learned coastal Carolina Algonquian from Manteo, the Carolina Native who stayed with the Roanoke colonists. Because Harriot could speak and understand the language, he wrote that he had had “special familiarity with some of their priests.” The chance to talk with Uttamattomakin and further his own understanding of the Algonquians’ religion and beliefs about creation and the afterlife was a wonderful opportunity for Harriot.50

Capt. John Smith also seized the opportunity to visit Pocahontas in Brentford. While she was in London, the Virginia Company had kept close tabs on her and decided who could visit her, but Smith had access to her in the country. Now that she had become a celebrity, he played up his earlier association with her. He wrote a letter to Queen Anne, James I’s wife, about Pocahontas and about the help she had given to the Jamestown colony in its most difficult time. In writing about Pocahontas, he was also highlighting his own role in the colony’s early years, and his account was filled with personal tags to elicit an emotional response. For an ordinary Englishman to write to the queen of England was a bold move, and he took the further liberty, several years later, of publishing the letter.51

Smith also published an account of his meeting with Pocahontas in Brentford. At first, it was disappointing, because when Pocahontas saw Smith, she “turned about, obscured her face, as not seeming well contented.” She was angry at him for staying away while she was in London. Rolfe suggested that they leave her alone, which they did for several hours, during which time Smith was “repenting myself for having writ that she could speak English.” When they rejoined her, Pocahontas began to talk, and she chided Smith, reminding him of all she had done for the colonists, and said, “You did promise Powhatan what was yours should be his, and he the like to you.”52

Pocahontas remembered that Smith had referred to Powhatan as “father, being in his land a stranger,” and she said that now that the situation was reversed, she would call Smith father. He said that he did not dare to allow that in England because she was a king’s daughter, at which Pocahontas exploded. He had acted without fear in Virginia, and yet in his own country, he was afraid of a word! She insisted that she would call him “father” and he would call her “child and so I will be for ever and ever your Countryman.” She wanted to restore the close friendship they had had in America.

Then Pocahontas went on to set the record straight. The colonists had told the Powhatans that Smith was dead, but Powhatan had directed Uttamattomakin to seek him out and learn the truth: “because your Countrymen will lie much.” Smith was clearly proud of his relationship with Pocahontas and her people. Smith wrote that he visited her several times with various friends and courtiers, and he reported that all those sophisticated men told him that she exceeded many English ladies in both her appearance and her behavior.

As spring approached in 1617, the Rolfes made preparations to return to America. The Virginia Company had invested heavily in making the visit a success in order to attract the favorable attention that its project needed. Chamberlain, ever scornful, spoke for at least some of the investors when he sent Pocahontas’s picture to his correspondent in the Netherlands: “Here is a fine picture of no fair Lady and yet with her tricking up and high style and titles you might think her and her worshipfull husband to be sombody, if you do not know that the poor company of Virginia out of their poverty are fain to allow her four pound[s] a week for her maintenance.”53 Four pounds was a lot of money. Still, it was a bit much to think that Pocahontas and her entourage, torn from their own country, should be self-supporting. And the four pounds presumably was to keep her entire household in London.

As the time for the party’s return to Virginia neared, the Virginia Company revealed the great scheme that was behind Pocahontas’s lavish treatment and the important people she had met. In February 1616, even before the Rolfes had arrived, King James had ordered the two archbishops, of Canterbury and York, to direct every parish in the country to take up a collection for money to set up schools and churches among the Powhatans in Virginia, “for the education of the children of those barbarians.” Uttamattomakin had told Samuel Purchas that he was too old to be converted and said that the English should start with the children; his thinking matched what English leaders had already decided. The royal command said that the collection was to occur every six months for two years, four collections in all. Some bishops suggested to the parish officers that the collection should be done house to house to make sure that everyone contributed. Just as the Rolfes were awaiting a favorable wind, the Virginia Company did something remarkable. On March 2, the company received £300 that had been raised in the parishes all over England. A week later, it appropriated a third of that sum to the Rolfes to be used in educating Powhatan children and in converting the Powhatans to Christianity. The actual grant said that it was £100 “for the Lady Rebecca . . . for sacred use in Virginia.” The company recorded that John Rolfe promised “in behalf of him self and the said Lady, his wife,” to use all “good means of persuasions and inducements” to win the Virginians to the “embracing of true religion.”54

These plans came to nothing. Pocahontas died as the ship that would have carried her home sailed down the Thames, and she was buried in the chancel of St. George’s Church at Gravesend on March 21, 1617. Burial in the chancel was reserved for people of high rank, so her status was reaffirmed in this final English scene. As with the inn the party lived in, the Belle Sauvage, the name “Gravesend” seems to have a special affinity with Pocahontas’s story, but just as the inn name derived from previous owners, the name “Gravesend” originally referred to the medieval office of landgrave, or count, and the edge of his jurisdiction.55

The sources are frustratingly skimpy on how or why Pocahontas died just as she was entering her twenties. Her lungs had been troubling her, and pneumonia or even tuberculosis may have been the cause. But there are also reports of her profound unhappiness with the prospect of returning to Virginia. Chamberlain, reporting the gossip, wrote that the Rolfes were waiting for a good wind to take them back across the Atlantic but that it was “sore against her will.”56 It seems highly possible that she was suffering great inner conflict because of that Virginia Company grant and the promise that she would devote herself to converting her people to Christianity. As long as she was in England, or even in the English colony, she could occupy the role of the celebrated first convert. But to go among her own people and try to subvert the very basis of their culture and traditions must have seemed impossible to her.

Pocahontas remembered Paquiquineo’s story of having been trained by Spanish priests and returned to Virginia to convert his people. Paquiquineo solved his problem by destroying the mission that brought him back in the 1570s, but Pocahontas, as the mother of young Thomas, was tied to the English in ways that were quite different. Her inner turmoil over what would happen once they were back in Virginia must have been intolerable. What we call stress-related illness seventeenth-century people called a broken heart, and some said Pocahontas died of a broken heart. Whatever physical illness she had was made far worse by the stress she felt.

Henry Spelman had seen death before. His father died when he was eight, and early death was common in the England of his time. He had been so good with Iopassus’s young child, and we can imagine him coming forward to comfort Thomas Rolfe and soothe his crying as the baby longed for his mother. Thomas was apparently inconsolable, and even Henry’s efforts were not enough.

As soon as Pocahontas was buried, the ship carrying Henry, John Rolfe, and baby Thomas traveled on, with Samuel Argall once again in command, but they stopped at Plymouth on England’s west coast. Thomas was not doing well, and Rolfe and Argall feared he would not survive the rigors of the ocean passage. He was sent to live with his uncle Henry Rolfe, so the boy grew up in John Rolfe’s home in Heacham. He never saw his father again.

Uttamattomakin and Mattachanna also sailed with the company, although some of their people stayed behind. One man lived with George Thorpe, who later went to Virginia with big plans for mass conversion. The Virginian was baptized with his protector’s name two weeks before he died, and the records of St. Martin’s in the Fields noted the burial of “Georgius Thorp, Homo Virginiae,” on September 27, 1619.57

Two of the women who attended Pocahontas remained in London. Both were Christians, and they had taken the names Mary and Elizabeth. Mary, who had worked as a servant for a while, became “very weak of a consumption,” which was how the English described tuberculosis. The Virginia Company allocated twenty shillings a week for her medicine to Rev. William Gough, who “hath great care and taketh great pains to comfort her both in soul and body.” Reverend Gough was pastor of St. Anne’s in the Blackfriars and cousin to Rev. Alexander Whitaker. He was the cousin to whom Whitaker had written in 1614 about Pocahontas’s conversion and marriage.58

By 1621, the company was chafing at the cost involved in keeping the two women. It decided to send them to Bermuda, which belonged to a spin-off from the Virginia Company, and the company sent them off in state. Each woman was provided with two servants, which would make her more attractive to a potential marriage partner, and clothes and bedding, soap and starch, food, a Bible, and a psalter. The total cost was over seventy pounds. The company instructed Nathaniel Butler, the Bermuda governor, to be especially careful in “bestowing of them,” as they were daughters of viceroys in Virginia.59

Mary died on the ocean voyage, but Elizabeth was married in the Bermuda governor’s front room to “as agreeable and fit husband as the place would afford”; the ceremony, witnessed by over a hundred guests, was followed by a lavish feast of “all the dainties” that could be provided. The governor described the bride as the sister of Opechancanough and a princess in her own right. Officials hoped that she and her husband might eventually go to Virginia and take on the conversion job they had planned for Pocahontas and John Rolfe.60

Henry Spelman now returned to Virginia with the rank of captain, so he had achieved the recognition of his adult status that he had craved. As he moved out of nonage, he hoped for a new, more independent life in Virginia and one in which his special skills would be recognized and valued.