1

“A Major Show in Television That People Will Talk About”

The Birth of an American Institution

The story of Saturday Night Live begins with the “King of Late Night” himself—Johnny Carson. In the 1970s, Carson was NBC’s biggest star, and the highly rated The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson (1962–1992) was one of the network’s top moneymakers. Since January 1965, NBC affiliates had the option of airing a rerun of The Tonight Show after the local 11 p.m. news on either Saturday or Sunday night. Nine years later, at Carson’s request, NBC pulled the show from its weekend late-night schedule. Carson may have decided America didn’t need to hear “Heeeeere’s Johnny!” six nights a week, or perhaps he was just thinking ahead. In December 1977, New York Times media critic Les Brown reported that Carson negotiated a new contract with the network raising his annual salary to $3 million and cutting his work schedule down to three shows a week for half the year. A guest host subbed for Carson on Monday nights, but on his second night off NBC aired a repeat of The Tonight Show.

Whatever Carson’s reasons, Herbert S. Schlosser, president and CEO of the National Broadcasting Company, agreed it was a good idea. Keeping the network’s highest-paid star happy was certainly a priority, and giving America a break from Carson over the weekend would certainly not affect the show’s stellar ratings. Schlosser expressed this point in a memo dated February 11, 1975, to NBC Network president Robert T. Howard: “There is a question in my mind whether or not telecasting the Saturday/Sunday ‘Tonight Show’ repeats may not in the long run begin to hurt us. The ‘Tonight Show’ has now reached an all-time peak. Certainly overexposure of a repeat on the weekend can’t help what we have going Monday through Friday.”

Like most programming decisions, the primary reason NBC agreed to the schedule change was financial. The hole in the weekend schedule provided the network with the opportunity to generate additional revenue by creating a brand new show that affiliates could air either on Saturday or Sunday night. The show also fit into the NBC family of shows that began with Today and The Tonight Show in the 1950s and continued with Tomorrow and The Midnight Special.

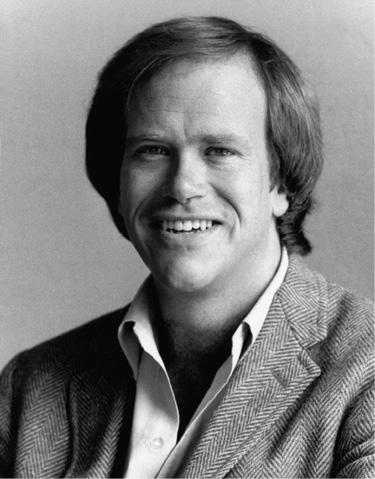

Twenty-six-year-old Dick Ebersol, NBC’s director of weekend late-night programming, oversaw the development of NBC’s Saturday Night and produced the show in the 1980s.

At the time, The Tonight Show was on weeknights from 11:30 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. On Mondays through Thursdays, Carson was followed by Tomorrow (1973–1981), a talk show hosted by Tom Snyder and launched by Schlosser in 1973. On Friday nights, The Midnight Special (1973–1981), a taped concert series, aired after The Tonight Show from 1:00 a.m. to 2:30 a.m. As Schlosser explained in a 2007 interview for the Archive of American Television (AAT), “I thought it was kind of a no-brainer. If you can get people to watch on 1 o’clock on Friday night, what’s wrong with Saturday night? And at 11:30—an earlier hour—I really thought that would work.” To develop the new late-night Saturday show, Schlosser hired twenty-six-year-old Dick Ebersol as NBC’s director of weekend late-night programming. At the time, he was working as an assistant to Roone Arledge, president of ABC Sports.

The original model for Saturday Night Live’s format was The Colgate Comedy Hour (1950–1955), a 1950s variety series that had not one but several hosts who rotated each week. In a 2009 interview for the AAT, Ebersol recalled how he was happy and surprised when Richard Pryor, whose edgy brand of stand-up comedy was hardly censor friendly, accepted his offer to be one of the hosts. As a result of landing Pryor, Ebersol was also close to signing George Carlin and Lily Tomlin. But Pryor suddenly dropped out at the urging of his new manager, who told him that he could never do his own material on network television. Losing Pryor was a setback for Ebersol, and the idea of rotating hosts was eventually dropped.

In the same February 11 memo to Robert T. Howard, Schlosser outlined his vision for “a new program concept called ‘Saturday Night.’” The memo, consisting of eleven “considerations and questions” (excerpts of which are included below in italic), served as the blueprint for a “new and exciting program” that would one day become an American comedy institution.

1. This program would play from 11:30 PM to 1:30 AM Saturday night in place of the Saturday/Sunday “Tonight Show,” each Saturday except when “Weekend” is on. What arrangements would we make with stations to help get maximum clearance on Saturday night? (Note: the program would be two hours long.) To the extent that we do not affect clearance on Saturday night stations could play it on Sunday night while we work towards greater Saturday night clearance. But under what title would the show play on Sunday night? Would we have separate titles for those stations who play it on Sunday night?

According to Ebersol, the Saturday vs. Sunday scheduling time was still an issue at this point because only one rerun of The Tonight Show aired each weekend: on Saturday night for 65 percent of the NBC affiliates and on Sunday night for the remaining 35 percent. But the affiliates would no doubt recognize that the new show’s major selling point is that it was live (and had Saturday in the title).

The length of the show was cut down from two hours to ninety minutes (same as The Tonight Show, which Carson trimmed to sixty minutes in 1980). Weekend (1975–1979), the other program mentioned in the memo, was a Peabody Award–winning late-night news magazine show hosted by Lloyd Dobyns that combined investigative reporting with light feature stories. The show continued to air on Saturday nights on the weeks SNL was “dark” (meaning not airing live) until 1978 when it was added to NBC’s prime-time schedule.

2. This would be an effort to create a new and exciting program. “Saturday Night” should originate from the RCA Building in New York City, if possible live, from the same studio where we did the “Tonight Show” or perhaps from [Studio] 8H.

The RCA Building (30 Rockefeller Center, or, thanks to Tina Fey, better known today as “30 Rock”) has been SNL’s home since 1975. The show is broadcast from Studio 8H (on the eighth floor), and the writers’ offices occupy the seventeenth floor. Studio 6-B, home to The Tonight Show from 1957 until the show relocated to Burbank in 1972, is the future home of The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon.

3. It would be a variety show, but it would have certain characteristics. It should be young and bright. It should have a distinctive look, a distinctive set and a distinctive sound.

From Edie Baskin’s title sequences, to the imaginative production and costume design of Eugene and Franne Lee, to the jazz theme song by musical director Howard Shore, Saturday Night Live, from the very beginning, had a very distinctive youthful, and for want of a better word, “hip” look and sound. The comedic sensibility of the cast and the writers, most of whom were under thirty, would also be a major factor in capturing the show’s young target audience.

4. We should attempt to use the show to develop new television personalities. We should seek to get different hosts who might do anywhere from one to eight shows depending on our evaluation of each host. It should be a program where we can develop talent that could move into prime time, either in the summer, as a January replacement, or even in the fall. It would be a great place to use people like Rich Little, Joe Namath, and others. If we give the show sufficient style and promotion it could attract certain guest stars because of the uniqueness of the show.

5. The show should not only seek to develop new young talent, but it should get a reputation as a tryout place for talent.

The idea of rotating hosts was part of the original concept, but the network settled on the idea of a new guest host each week. While it made SNL unique, it was not exactly an original idea. The Midnight Special, for most of its run, also had a different host each week. Singer Helen Reddy hosted for one season (1975–1976), but for the other five years The Midnight Special was hosted by a singer or comedian, including three of SNL’s early hosts: George Carlin, Richard Pryor, and Lily Tomlin. (Frequent SNL guest Andy Kaufman and original cast members Chevy Chase and Laraine Newman guest hosted during its final season in 1980–1981.) During the six-year period (1975–1981) when SNL and The Midnight Special were both on the air, they also showcased some of the same musical talent.

In terms of guest hosts, producer Lorne Michaels took a unique approach by not limiting hosting duties exclusively to comedians and musical performers. During seasons 1–5, SNL boasted an eclectic list of guest hosts that included television legends Desi Arnaz (1.14) and Milton Berle (4.17), White House press secretary Ron Nessen (1.17), Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner (3.3), activist Ralph Nader (2.11), veteran character actors Broderick Crawford (2.16) and Strother Martin (5.17), athletes O. J. Simpson (3.12) and Bill Russell (5.3), and television producer Norman Lear (2.2).

SNL certainly did live up to Schlosser’s original concept in regard to using the show to “develop new young talent,” yet Michaels didn’t necessarily see SNL as a training ground for future prime-time stars. Rich Little and the New York Jets’ star quarterback Joe Namath, who had recently signed a contract with NBC, never hosted or even made a cameo appearance on SNL. Rich Little briefly had his own comedy-variety series on NBC (The Rich Little Show) in 1976. Namath, who made frequent guest appearances on talk shows (he even guest hosted The Tonight Show), was given his own sitcom, the short-lived The Waverly Wonders (1978), in which he played a high school basketball coach. According to Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad’s Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live, Little’s name was brought up again to Michaels and Ebersol during a meeting. Schlosser added the name of another NBC favorite to the talent list—Bob Hope. Keeping his young target audience in mind, Little and Hope were exactly the kind of performers Michaels wanted to avoid.

6. As indicated, if possible the show should be done live. If it were done live at 11:30 PM it would permit people from Broadway shows to appear on it on Saturday night. However, if not done live it should be taped earlier in the evening the same day it goes on the air to maintain its freshness and topicality.

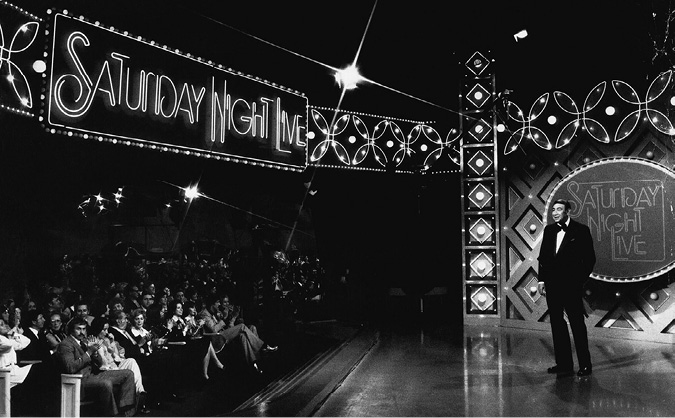

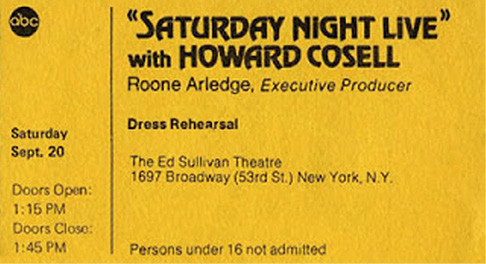

A live weekly variety show was certainly a novel idea in 1975, yet SNL was not the only live show to be added to the fall 1975 television schedule. On September 20, 1975, nearly one month before the premiere of NBC’s Saturday Night, Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell debuted in prime time on ABC. Broadcast live from the Ed Sullivan Theatre in New York City (the current home of the Late Show With David Letterman [1993–present]) with live remotes from around the world, the premiere episode featured singers John Denver, Paul Anka, and Shirley Bassey; from London, the British pop group the Bay City Rollers; and from Las Vegas, entertainers Siegfried and Roy.

Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell’s executive producer (and Dick Ebersol’s former boss), Roone Arledge, managed to book A-list performers like Bill Cosby, Roberta Flack, Frank Sinatra, and George Burns; star athletes, including Walt Frazier, Willie Mays, and O. J. Simpson; and an assortment of B-list celebrities and comedians. But Arledge came from the world of sports and knew nothing about putting on a live, weekly variety show. The same can be said for Cosell, who was his usual irritating self. It was no surprise when the show was a critical and ratings failure. In his interview with the AAT, the show’s director, Don Mischer, admitted the Cosell show was “chaotically produced,” dubbing it “one of the greatest disasters in the history of television.”

“Live from New York . . . It’s Howard Cosell!” Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell premiered three weeks before NBC’s Saturday Night at the start of the 1975–1976 TV season. Unfortunately, Cosell was no Ed Sullivan, and the show was canceled four months later.

Once ABC yanked Cosell from their Saturday night lineup in January 1976, NBC obtained the rights to the title, which was officially changed on March 26, 1977, to Saturday Night Live. This was not the only connection between the two shows. Cosell’s show featured three comedy performers, billed as “The Prime Time Players,” which is how SNL arrived at the name “The Not Ready for Prime Time Players” for their original cast. Better yet, the three Cosell regulars—Bill Murray, Christopher Guest, and Brian Doyle-Murray—would all eventually become SNL regulars. According to Chevy Chase’s biographer, Rena Fruchter, Chase originally wanted to call the show Saturday Night Live Without Howard Cosell, but NBC wouldn’t allow it (no surprise there).

7. All of this sounds like a very expensive, high budget show. It should not be that. Based on sales and other projections we would have to determine a reasonable budget. Could we make out if it cost $85,000 to $125,000? What are the parameters? We should set a goal and hire a producer who can do it for the parameters we establish.

8. We should not look upon this effort in terms of a short term financial evaluation. We undertook “The Tomorrow Show” knowing that we might only break even for some period of time.

Schlosser understood that it took time and money to create a hit television show. According to Hill and Weingrad, in the early days SNL cost far more than it was making. The cost per episode was initially estimated at $134,600, but the show was going approximately $100,000 over budget per episode, and the network was only getting $7,500 for a thirty-second commercial spot. Once SNL’s status as a hit show was established, NBC was spending $406,000 per episode (season 4), which rose to $553,000 per episode (season 5, the first season the show came in under budget). According to Shales and Miller’s Live from New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live, the ratings for season 4 were at an all-time high of 12.6 and 39 percent share (that’s the percentage of homes with their television sets on that were watching SNL). In the plus column, the show was earning the network somewhere between $30 and $40 million a year.

9. Saturday night is an ideal time to launch a show like this. Those who now take the Saturday/Sunday “Tonight Show” repeats should welcome this and I would imagine we could get much greater clearance with a new show.

A ticket to the dress rehearsal of the premiere episode of Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell (1975–1976).

Schlosser concludes on an optimistic and foretelling note: “With proper production and promotion, ‘Saturday Night’ can be a major show in television that people will talk about.” When asked about his contribution to the making of Saturday Night Live, the NBC executive quite humbly admits he didn’t really meddle in the content of the show, only fielded the weekly complaints from the head of standards and practices. In his interview for the AAT, he credited producer/creator Lorne Michaels for giving him more than what he outlined in his memo: “What he gave me was not only more than I thought, it was really a new kind of show, it was a breakthrough . . . nobody was doing what he was doing on television. Nobody.”