7

Season 6—The Worst Season (So Far)

The 1980s, Part 1 (1980–81)

“The new version—new cast, writers, and producer—had no compensating satirical edge. It was just haplessly pointless tastelessness.”

“[T]he shows were just not watchable.”

“We did suck. I can’t blame it all on the press. The show sucked.”

On March 7, 1981, in the cold opening of episode 6.12 of Saturday Night Live, the show’s seven new cast members—Denny Dillon, Gilbert Gottfried, Gail Matthius, Eddie Murphy, Joe Piscopo, Ann Risley, and Charles Rocket—visit guest host Bill Murray in his dressing room to commiserate over the negative press the show and the cast have been receiving since the season 6 opener back in November. In his signature half-joking manner, Murray quotes from some of the show’s actual reviews (the critics are not identified): “Saturday Night Live is Saturday Night Dead,” (Newsday’s Marvin Kitman); “From Yuks to Yeccch” and—Murray’s favorite—“Vile from New York” (both by the Washington Post’s Tom Shales).

Murray offers each cast member some constructive criticism. He tells Rocket he’s funny, but warns him to watch “his mouth” (Rocket dropped an f-bomb during the “good nights” the previous week [6.11]). Murray pats sad-eyed Gottfried on the back and tells him to “cheer up”; recommends frizzy-haired Dillon comb her hair; suggests Piscopo change his last name; and compliments Risley and Matthius on their looks, but admits he can’t tell them apart. Finally, he turns to nineteen-year-old Murphy, who was promoted to a regular player a few weeks back, and says, “You’re black . . . that’s beautiful. You can do whatever you want.”

Murray then launches into the same “anti-motivational” speech he delivered in the summer camp comedy Meatballs (1979) to the kids at North Star Camp, who were the underdogs going into a competition against a rival camp. Murray leads them in a chant: “It just doesn’t matter! It just doesn’t matter!” Suddenly, he realizes if he goes out there, he risks humiliating himself in front of millions of people. He panics and reaches for a drink, but the cast stops him. Together they open the show with “Live from New York, it’s Saturday Night!”

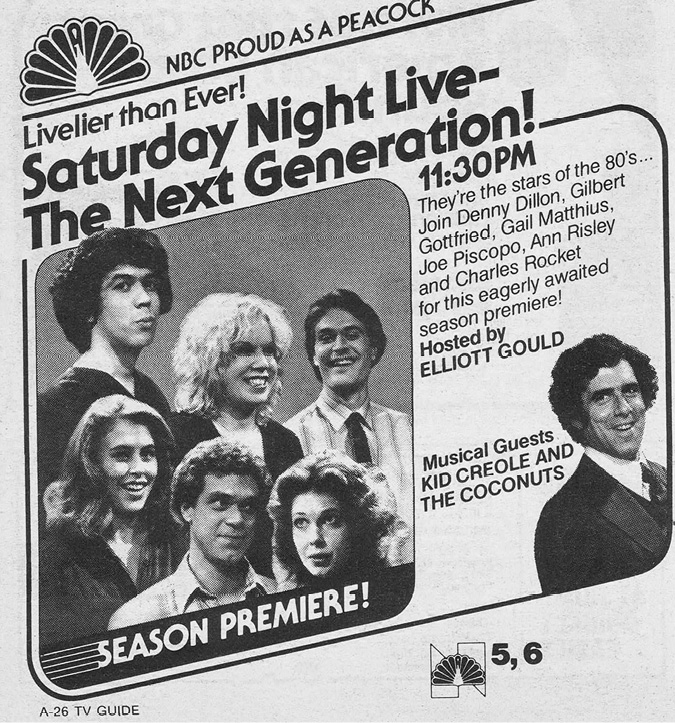

Advertisement for the premiere of season 6 of SNL highlighted the show’s six new cast members.

It’s understandable why Murray panicked. The reviews were abysmal, and while there was plenty of finger-pointing going on both inside and outside the walls of 30 Rock, it was producer Jean Doumanian, the cast, and the writers who, deservingly so, bore the brunt of the blame by the critics. Gary Deeb, critic for the Field Newspaper Syndicate, called the new season of Saturday Night Live “embarrassing” to the network. “The new cast of Saturday Night Live is pretty terrible, so are the dozen new ‘comedy’ writers who dredge up the rotten material to be performed.” In his review of the season opener, Los Angeles Times critic Howard Rosenberg directed his remarks to the writers: “For much of Saturday’s debut, the writing was sophomoric, or even banal, either close to the vest or crude rather than creative. The writers (they’re all new, too) sought security in cheap targets: Anita Bryant, Jimmy Carter.” Rosenberg also felt the show only “regained its old zest” with the short films (Foot Fetish and “Gidgette Goes to Hell”). The harshest review, entitled “Yuk to Yeccch,” was by Shales, who found the new SNL to be “a snide and sordid embarrassment.”

Thanks to Murray, the next ninety minutes was a major improvement over the first ten episodes. The sketches even managed to generate some genuine “yuks” from the studio audience. In the first (and best) sketch, Murray is a writer whose characters come to life in the background as he composes his next novel. Unfortunately for them, the writer keeps changing his mind, so the characters are scrambling around trying to keep up, resulting in some very funny bits of physical comedy. In Altered Walter, a parody of the film Altered States (1980), Murray impersonates the recently retired Walter Cronkite, who now spends all of his time holed up in a sensory-deprivation tank in search of “the big story.” Murray also revisits some of his old characters. He sings up a storm as Nick Rivers, who performs in the Paddlewheel Lounge aboard the Riverboat Queen during a Mardi Gras cruise (his musical selections include “Proud Mary” and “Celebrate Good Times”). It’s too bad the boat never made it to New Orleans due to engine trouble, and the passengers had to celebrate Mardi Gras on a dock in Cincinnati. On the revamped Weekend Update (renamed Saturday Night Newsline), Murray does his annual Oscar predictions, but throws out all the nominees and predicts all of his former castmates will win: Best Supporting Actress: Laraine Newman in Wholly Moses! (1980); Best Supporting Actor: Chevy Chase in Oh Heavenly Dog (1980); Best Actress (it’s a tie): Jane Curtin in How to Beat the High Cost of Living (1980) and Gilda Radner in Gilda Live (1980) and First Family (1980), etc. Best Picture goes to Murray’s film Caddyshack (1980).

Later, at approximately 12:58 a.m, Murray stands center stage, surrounded by the cast, ready to say good night. But before he does, he looks into the camera and addresses his former castmates directly: “Danny, John, Gilda, Laraine, Garrett, Jane . . . I’m sorry for what I’ve done.” The current cast bursts into laughter. Murray gives the audience a half smile and waves. Once again, it’s not clear if he really meant what he said. As the cast moves in for a group hug, Murray looks very uncomfortable.

So what was Murray really thinking at that moment? Did he really feel the need to apologize for trying to salvage what the critics and NBC executives already considered a sunken ship? In Shales and Miller’s Uncensored History, Murray revealed that he contacted the show’s new producer, Jean Doumanian, and offered to host. “It was a tough week,” he recalled. “We worked really hard writing and rewriting, and the show turned out good, and I thought, ‘This could work.’” But even the talented Bill Murray couldn’t prevent NBC from giving Doumanian the axe, bringing her twelve-episode stint as SNL’s second producer to an abrupt end.

Doumanian, who had been with the show since 1975 as a talent coordinator (her title was changed to “Associate Producer” beginning with episode 2.2), was hired to succeed Lorne Michaels at the end of season 5. At that time, the remaining cast’s five-year contracts were up, and the writers were ready to move on, although director Dave Wilson and some members of the production staff stayed with the show. Lorne Michaels reportedly would have stuck around if NBC had met his terms.

Jean Doumanian, SNL’s second producer, remained with the show for only twelve episodes.

On June 17, 1980, Tony Schwartz did a New York Times story on Michaels’s departure from the show and the hiring of Doumanian as his successor. According to Schwartz, Michaels decided to quit after long negotiations and settled for a one-year deal with NBC to develop shows for prime time and late night. He spoke candidly to Schwartz about how the “spirit” of SNL had changed over the years: “As everyone became more and more successful, and got other offers, it was harder to do. The show was purer in the first three years. I don’t think it became decadent, I just think it became successful.” He added that he wanted to do something different and felt he couldn’t create that by the start of the next season in September.

Meanwhile, Doumanian shared her “vision” for the future of SNL: “I want to keep the elements that have made ‘Saturday Night’ great, the repertory company, the guest host, showcasing music, and to add new dimensions. I feel as if we’re beginning a new show, because there will be an entirely new cast and I’ll bring my own ideas to it. The challenge is to see if we can grow and still keep our audience.” Doumanian was a surprise choice—especially for Michaels. When he created the show, he was an experienced television comedy performer, writer, and producer with an Emmy on his shelf (for writing Lily Tomlin’s 1973 special). As Michaels explained to People magazine’s Richard K. Rein, Doumanian was a booker (the person responsible for booking the hosts and musical acts): “The job was important, but it had nothing to do with the spirit, the improvisation, what the show should be about. The writers and performers were a family, but Jean was never a part of that group.”

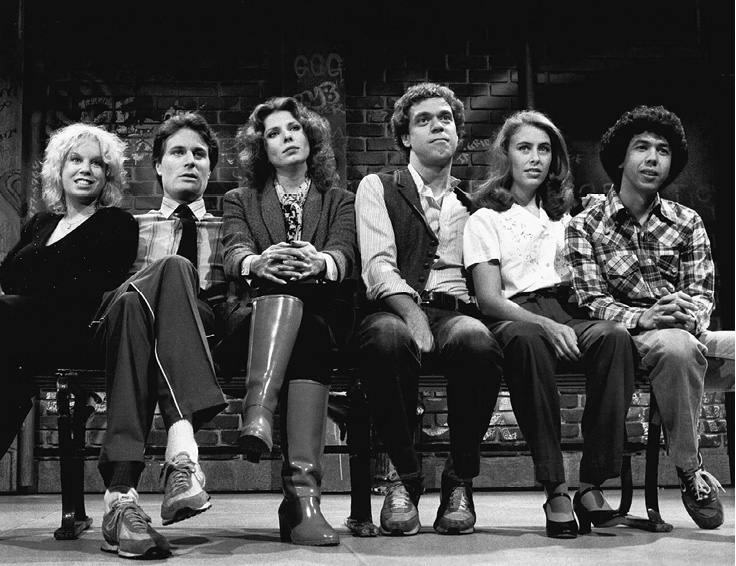

Saturday Night Live cast members for season 6: (from left to right) Denny Dillon, Charles Rocket, Ann Risley, Joe Piscopo, Gail Matthius, and Gilbert Gottfried.

Four months later, in mid-October 1980, Schwartz wrote another piece for the New York Times in which he revealed the names of the six new cast members. Variety later reported that Doumanian leaked their names to Schwartz after a “disgruntled ex-staffer” gave them to the New York Daily News (ironically, the Times published them first). Consequently, a big press conference NBC had planned to introduce the new cast was canceled, and Doumanian’s bosses, NBC president Fred Silverman and president of NBC Entertainment Brandon Tartikoff, were not pleased she leaked the names to Schwartz without their knowledge.

Like the Not Ready for Prime Time Players, the six new cast members all had limited television experience:

• Denny Dillon appeared on Broadway in the 1974 Angela Lansbury revival of Gypsy, a short-lived 1975 revival of The Skin of Our Teeth, and a stage adaptation of Harold and Maude. She also had a small role in the film Saturday Night Fever (1977) and was a regular on NBC’s Hot Hero Sandwich (1979–1980), a Saturday morning television show featuring comedy sketches and musical performances shot in Studio 8H (sound familiar?).

• Gilbert Gottfried was a stand-up comic in New York.

• Gail Matthius, an actress from Sioux Falls, South Dakota, had been performing in comedy clubs in Los Angeles.

• Joe Piscopo, a New Jersey native, appeared in regional theater productions and on The Merv Griffin Show (1962–1986).

• Ann Risley was a character actress who had small roles in several Woody Allen films (Annie Hall [1977], Manhattan [1979], and Stardust Memories [1980]).

• Charles Rocket was a former news anchor in Providence, Rhode Island; Pueblo, Colorado; and Nashville, Tennessee; and a front man for a number of bands before pursuing a career in comedy.

Rounding out the cast were three featured players—Yvonne Hudson, Matthew Laurance, and Eddie Murphy, who was the only one promoted to a full cast member (6.8).

Doumanian was smart to play it safe and ask Elliott Gould, who had hosted SNL five times, to host the season opener (at this point, Buck Henry held the hosting record with ten). She told the Associated Press’s Tom Jory that she “thought it would be a good idea to have someone who had done the show before.” Granted, Doumanian was aware of the challenges she was about to face. “It’s really like it was starting the show five years ago. But it’s tougher because the audience has a preconceived idea of what the show should be like. I have to sell it all over again.”

Season 6, episode 1 of Saturday Night Live opens with a funny bit: Gould wakes up in a large bed with the six new cast members, each of whom introduces himself or herself as a cross between two of the show’s original cast members: Matthius is Gilda + Jane, Rocket is Chase + Murray, Risley is Gilda + Laraine, and Gottfried is Belushi + “that guy from last year . . . nobody could remember his name” (Harry Shearer). When Piscopo, who apparently isn’t a cross between anyone, asks Gould about drug use backstage on the old show, the host tells him “cocaine was everywhere” and everyone used it, even Tom Snyder, Roger Mudd, Tom Brokaw, Edwin Newman—“they all snort a few lines” before they go on. Finally, the sixth cast member, Denny Dillon, appears from under the covers and officially opens season 6 by saying, “Live from New York, it’s Saturday Night!”

Even to this day, SNL’s season opener is not necessarily one of the better episodes of the season. The writers and the cast usually need a few episodes to find their comedic footing. Those involved in season 6 were also under the added pressure of trying to live up to the show’s legacy (even if season 5 was not the strongest due to the absence of Belushi and Aykroyd) and, at the same time, to some extent, reinvent the wheel. Season 6 failed to do either. There’s no question that as producer, Doumanian was the one who was ultimately responsible for what goes on the air. But television is a collaborative medium, so it is only fair that everyone involved bear some of the responsibility as well, and in the case of SNL’s season 6, there was certainly enough blame to go around.

In the early years of SNL, political satire was one of SNL’s strong points, thanks to Chevy Chase’s hilarious portrayal of President Ford as a clumsy idiot and Dan Aykroyd’s dead-on impersonation of President Carter. Season 6 debuted eleven days after the 1980 presidential election. The Carters would soon be returning to Georgia, while Nancy and Ronald Reagan were heading east to Washington, D.C. But the new SNL floundered in both its comedic treatment of the transition and the Reagans’ first few weeks in the White House.

In the first official sketch of season 6, Rosalynn Carter (Risley) convinces her depressed husband that losing the election was a good thing because now they can resume their sex life. The characterization of the First Lady as undersexed comes out of nowhere, though there is an allusion to Carter’s admission in a November 1976 interview with Playboy that he “looked on a lot of women with lust.” (“And now honey,” Rosalynn says, “you can release all those lustful thoughts.”) The sketches about the Carters were not satirical pieces. They had very little to say about the public image of the outgoing president and his family. A few weeks later, right before Reagan’s inauguration, Carter is seen sitting in a Washington bar drowning his sorrows, while the guy next to him, who doesn’t recognize the president, tries to cheer him up (6.6). In the cold opening of the following week, the Carters spend President Reagan’s Inauguration Day dismantling the interiors of the White House (6.7).

The early Reagan sketches also didn’t work due to in part to Charles Rocket’s weak impersonation of Ronald Reagan, who is portrayed as a clueless, doddering old man. In a speech to the American people about the state of the economy, Reagan uses what look like a child’s drawings to illustrate his points (6.9). The saving grace of two other sketches is Joe Piscopo’s impersonation of Frank Sinatra, who, along with Nancy Reagan (Gail Matthius), is really running the show (6.7). In the last sketch (6.10), Reagan addresses the nation and publicly clears Sinatra’s name in regard to his alleged ties to the mob. After denying he knows Manny the “Horse” and Louie the “Squid,” Sinatra asks Reagan to pose for a picture with Sinatra’s buddies, who all look like hoodlums.

Several new cast members were added for the final show of season 6 (6.13), including (left to right) Laurie Metcalf, Tony Rosato, Robin Duke, Tim Kazurinsky, and Emily Prager. Metcalf appeared in only one episode, and Prager was never seen on camera because all of her sketches were cut after dress rehearsal.

Rocket was better suited to play the role of anchor on Weekend Update. He not only looked the part, but before he became a comedian he was a professional news anchorman. But the writing was simply not as strong as past seasons, and there were problems with his delivery. Instead of playing the part of an anchorperson, something Chase and Curtin did so well, he delivered the news like he was doing stand-up by changing the intonation of his voice, putting unnecessary emphasis on certain words, and then reacting to what he just said. Rocket’s smug persona was much better suited for the Rocket Report, his filmed man-on-the-street interviews and reports. At one point he even travels down to Washington, D.C., to give a rundown of Reagan’s daily schedule, substituting unrelated film footage for what we are supposed to believe is actual footage of the president. Overall, he appeared more comfortable out in the field than behind the Weekend Update desk, where he occasionally stumbled over words while reading the news. But it didn’t matter because the jokes were often flat, and one too many punch lines were greeted with mild chuckles or dead silence from the studio audience.

Matthius, Piscopo, and Dillon were the most adept at creating characters, many of whom were recurring over the course of twelve episodes. Matthius introduced teenage valley girl Vickie in a sketch on the first episode in which she’s on a date with a forty-year-old businessman (Elliott Gould) (“Do you have a job or some junk?” she asks him). She really wants him to take her to the Homecoming Dance at school. Of course, he can’t, and she tries to hide that she’s upset by saying another guy is going to take her who is a Marine and “sort of black.” He reacts because he knows she’s lying. She calls him a racist and storms out, leaving this pathetic guy all alone.

Critic Randal McIlroy of the Winnipeg Free Press singled out Matthius as “the only new player with any flair for a line” and the sketch for its blend of “dark humor with pathos in the best Saturday Night Live tradition. It was funny in a bitter way and suggested that the new show may have a chance after all.” Critic Tom Shales, who was not amused by the season opener, remarked, “it was one of the few sketches with any sort of resonance or subtlety.” In later sketches we see Vickie and her best friend Debbie (Denny Dillon) pay a visit to Planned Parenthood (6.3), hang out at the Cedar Mall (6.5), go to a club to meet punk rocker Tommy Torture (host Ray Sharkey) (6.6), and talk to a girl (host Deborah Harry) who dropped out of high school (6.10).

Denny Dillon, who was a guest performer on SNL during season 1 (1.3), was by far the most enthusiastic and energetic member of the cast—the kind of performer who was up for anything. She specialized in brassy female characters, including kids like Amy Carter and Mary Louise, a nasty little British girl whose best friend is a sock puppet named Sam. Both she and Matthius certainly deserved to be asked back for season 7.

On the whole, the cast was also trapped in some really awful sketches. The second episode of the season (6.2), hosted by British actor Malcolm McDowell, included one misfire after another. In “The Leather Weather Report,” a leather-clad dominatrix named Thelma Thunder (Dillon) gives the weather forecast while beating a man (Rocket) who is tied horizontally across a map of the United States. The next sketch, “Commie Hunting Season,” is not only a season low point, it’s a candidate for the single worst sketch in the history of Saturday Night Live. The sketch opens with a bunch of southern hicks with their rifles in hand gathering for the opening day of “Commie Hunting Season.” The sketch was a response to a jury’s recent acquittal in Greensboro, North Carolina, of six members of the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party who were accused of shooting and killing five protest marchers, members of the Communist Workers Party, during a “Death to the Klan” rally on November 3, 1979. On November 17, a week prior to the airing of this sketch, the jury returned a not-guilty verdict on all five counts of murder. The sketch is in poor taste, and the studio audience responds with uncomfortable laughter and silence—especially when Uncle Lester (Charles Rocket) answers first-timer Jim-Bob’s (Joe Piscopo) question, “How can you spot a Commie if they ain’t demonstrating?” “All you got to do is shoot yourself a Jew or a Nigger,” Uncle Lester explains. Silence—ten seconds’ worth to be precise—though on live television it feels more like ten hours. The viewers at home obviously had the same reaction. According to the United International Press, the NBC switchboard in New York received 150 telephone calls complaining about the sketch in addition to complaints registered directly with the NBC affiliates in South Carolina. The sketch is intended to be satirical, but its use of racist language to combat racism is problematic. Unlike the Chase-Pryor “Word Association Sketch,” in which the audience is aligned with Pryor, no one in this sketch has a negative reaction to what’s being said.

There were also some missed opportunities. For example, in her monologue, Jamie Lee Curtis (6.4), whose reputation as a horror film scream queen was well established, treats the audience to her trademark scream. This was 1980—the height of the slasher film craze (Friday the 13th, Terror Train, and Prom Night, the latter two starring Curtis, were all released that year). But in SNL’s attempt at a horror parody, “The Attack of the Terrible Snapping Creatures,” Curtis and her roommate (Matthius) move into a new apartment inhabited by “snapping creatures” or as my mother like to call them—clothespins. Clothespins? Really? This was the best they could do?

Some of the best moments of season 6 were not live from Studio 8H. In the season opener, Elliott Gould introduces two shorts (he calls them “Short Shots”) by established directors: Foot Fetish, a stop-motion animated film by Randal Kleiser (Grease [1978]), and “Gidgette Goes to Hell,” a music video directed by Jonathan Demme (Silence of the Lambs [1991]), featuring the post-punk group the Suburban Lawns. Episode 6.4 included a truncated version of director Martin Brest’s film short from his days as a film student at NYU, Hot Dogs for Gauguin (1972), starring Danny DeVito. SNL also aired the pre-MTV cult music video “Fish Heads,” written and sung by Barnes and Barnes, a pair of fictional twins named Art and Artie Barnes, who are actually former child actor Billy Mumy and his childhood friend Robert Haimer. The song, recorded in 1978, was inspired by a meal at a Chinese restaurant during which an actual “roly poly fish head” was served. The song developed a cult following thanks to radio show host Dr. Demento, who appears in the video along with its director, actor Bill Paxton. Although they are more entertaining than the sketches, the inclusion of these films also contributes to the general unevenness of the season 6 episodes, which, from cold opening to the “Good nights” consisted of approximately twenty segments, as opposed to the average of fifteen segments that comprised the season 5 episodes. More importantly, most shorts featured on Saturday Night Live are produced by SNL’s resident filmmakers or members of the writing staff and cast, so their tone and style are in sync with the overall comedic tone of the show.

The highlight of season 6 was the addition of nineteen-year-old cast member Eddie Murphy. His first appearance is as an extra in a sketch, a spoof of Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, in which host Marlin Perkins (Charles Rocket) sends Jim Fowler (Joe Piscopo) out into the wild in search of a “Negro Republican” (6.1). Over the next few shows he begins to have speaking roles in sketches and introduce some of his characters like Raheem Abdul Muhammed and Mr. Robinson of Mr. Robinson’s Neighborhood. Neil Levy, the talent coordinator responsible for bringing the comic to Saturday Night Live, helped Murphy get an even bigger break when an episode was running five minutes short (6.6) and he suggested to Doumanian to let Murphy do part of his stand-up about “black people fighting.” Three shows later, Murphy’s name appears in the opening credits between Matthius and Piscopo as a cast member.

After the season 6 opener, the show’s ratings declined steadily. The first three programs averaged a 10.2 Nielsen rating and 30 percent share. The episodes that aired in comparable time periods the previous year (season 5) averaged a 14.2 rating and 40 percent share. Adding insult to injury, ABC’s Fridays (1980–1982), a sketch comedy airing late on Friday nights that was mostly dismissed as an SNL rip-off when it debuted in April 1980, was finding an audience. Although it was not in direct competition with SNL, the fact that Fridays was more popular than the show on which it was modeled was a kick in the teeth for NBC.

By December 1980, the problems SNL was facing were hardly an industry secret. A December 17 Variety article by John Dempsey entitled “‘Saturday Night Live’ Just Ain’t” outlined the “behind the scenes turmoil” involving Doumanian (who Dempsey predicted would be “gone by midwinter or sooner”) and the writers. What his sources describe sounds like a perfect storm of “creative dysfunction.” According to Dempsey’s anonymous sources, Doumanian was unqualified to be producer and needed to be in total control, which ultimately affected the content of the show, including her choice of hosts. Instead of choosing “strong comic performers” like Chevy Chase and Steve Martin, she chose actors who were less likely to question the material. With the exception of Elliott Gould (his sixth and final time hosting the show), former cast member Bill Murray, and Robert Hays, the guest hosts (Ellen Burstyn, Jamie Lee Curtis, David Carradine, Deborah Harry, Charlene Tilton) were not known for their comedic talents. She seemed to be more concerned with the quantity than the quality of sketches. Instead of writing a few sketches and devoting the rest of their time polishing and rewriting what they’d written, they were expected to continue to churn out more sketches. The writers also objected to Doumanian’s reliance on associate producers Letty Aronson and Michael Zannella for advice. Ironically, Aronson, younger sister of Woody Allen, who was a close friend of Doumanian’s, later replaced Doumanian as executive producer of her brother’s films after Allen sued Doumanian for allegedly cheating him out of an unspecific amount of profits for eight films (the suit was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount).

One individual who voiced his criticism of Doumanian was Irv Wilson, senior vice president of programming at NBC. Speaking on the record, Wilson told Dempsey that Doumanian “needs help badly. There’s a major writing problem, and the actors are not getting the proper staging. The show has no bite—it should be providing intelligent irreverence but instead it’s mostly taking cheap shots.” When a television executive criticizes a show on his or her own network, you know it’s just a matter of time before heads will roll.

In yet another New York Times article by Tony Schwartz about the current state of SNL, aptly titled “Whatever Happened to TV’s ‘Saturday Night Live’?” former head writer Michael O’Donoghue identified one of the show’s chief problems—“the absence of an identifiable point of view.” “Good humor exploits real tensions that are upsetting people,” O’Donoghue explained. “Ten years ago, sex and drugs were big issues, but now there are plenty of others things to be upset about: Iran, the hostages, the oil situation, Reagan. That’s where the humor ought to be coming from.”

On March 10, 1981, three days after her last show (6.12), Doumanian told Variety that she resigned “because the show had not attained the high standards I set for it. . . . By stepping aside, I hope the network will be successful in realizing the full potential of the show.” The article also announced that Dick Ebersol was hired by NBC to take over the show, which would go on a one-month hiatus.

Season 6 both resumed and ended with episode 6.13 due to the Writers Guild strike. One strategy Ebersol employed was something he felt should have been done with the first episode of season 6—an “on-air” transition between the old guard and the new. “The first show of the season was a repeat of the very first Saturday Night with all the original members,” Ebersol told the Los Angeles Times’ William K. Knoedelseder Jr. “The next week it was an entirely different show with all new people and no similar writers, so there was no familiarity for the audience out there.”

To bridge the past and the present, Ebersol enlisted Chevy Chase, who opens episode 6.13 with a trip down memory lane as he goes into a storeroom and finds remnants from the 1970s—his Land Shark costume, the Coneheads’ cones, and Mr. Bill, who Chase saves from a trashcan and then accidentally step on him. Chase is not the official host (there is none), so there’s no monologue. As for the cast, Gottfried, Risley, Rocket, and featured player Matthew Laurance were gone. Piscopo and Murphy remained, as did Dillon, Matthius, and Hudson, though this would be the last show for all three women (Hudson later appeared uncredited in sketches during seasons 7 and 8). The new players included two cast members from television’s SCTV—Robin Duke and Tony Rosato—and a member of Second City, Chicago, Tim Kazurinsky. There were two additional featured cast members: Chicago stage actress Laurie Metcalf and National Lampoon alum Emily Prager. Metcalf appeared in a filmed segment during Weekend Update in which she asked people on the street who they would take a bullet for and if they would take one for the president. Prager’s sketches were all cut in dress rehearsal, so she doesn’t appear in the show at all. Consequently, she is the only performer credited as a cast member to never appear on the show.

To really experience season 6 of SNL, you should hunt down bootleg copies of the thirteen episodes, though you can still get a sense of how bad it really was by watching the heavily edited, shortened versions available on Netflix.