10

Saturday Night Alive (and Dead)

The 1990s, Part I (1990–1995), Seasons 16–20

Between the years 1986 and 1990 (seasons 12–15), SNL boasted a stellar cast consisting of Dana Carvey, Nora Dunn, Phil Hartman, Jan Hooks, Victoria Jackson, Dennis Miller, and Kevin Nealon, who was promoted from featured to regular player in season 13. Mike Myers, who joined the cast as a featured player in the middle of season 14 (14.10), was bumped up to a regular at the start of season 15. A second featured player, some guy named Ben Stiller, started in March 1989 (14.15), but he only stuck around for six episodes. Three years later, Stiller and Judd Apatow created The Ben Stiller Show (1992), a one-camera sketch comedy show on the Fox Network featuring Janeane Garofalo, Andy Dick, and Bob Odenkirk. Although Fox pulled the plug after twelve episodes, the show won a Primetime Emmy for “Outstanding Achievement in Writing in a Variety or Music Program,” beating the writing staff of Saturday Night Live. Stiller did return to host SNL in 1998 (24.4) and 2011 (37.3).

As to be expected, some members of SNL’s cast decided it was time to move on. Jon Lovitz and Nora Dunn, who had both been there for five seasons, departed at the end of season 15. Dunn left amidst the controversy surrounding her public refusal to share the stage with host Andrew Dice Clay (15.19), though she did return for the season finale hosted by Candice Bergen (15.20). Lovitz later admitted in a July 1997 interview with Playboy that at the time he wasn’t sure if he had made the right decision. “Should I have left? I did that for about two years,” he said, “Then I got a job and I was OK.” At the end of season 16 (1990–1991), SNL lost two more major players: Dennis Miller, who had anchored Weekend Update for the past six seasons, and Jan Hooks, who headed to the West Coast to join the cast of Designing Women (1986–1993).

To prepare for the inevitable loss of the five remaining cast members (Carvey, Hartman, Jackson, Myers, and Nealon), Michaels started to stack the deck with new talent. Over the course of season 16 (1990–1991), he added seven featured players to the remaining two (A. Whitney Brown and Al Franken), bringing the total to nine. Three of them were from improvisational theater: Julia Sweeney was a Groundling, while Chris Farley and Tim Meadows worked together at Second City in Chicago. The remaining four—Chris Rock, Adam Sandler, Rob Schneider, and David Spade—were stand-up comics. All but Sweeney were in their mid- to late twenties, which was significantly younger than the outgoing and remaining “veteran” cast members with the exception of Mike Myers, who was twenty-five when he started on the show.

The fact that seven out of the eight newcomers were males under the age of thirty would have a significant effect on the show’s comic sensibility in the early 1990s. Their brand of humor appealed more to viewers like themselves.

Adam Sandler epitomized a brand of humor popular among the same demographic that watches Comedy Central, who Wired magazine’s Frank Rose describes as “white, college-educated, post-frat-boy males.” On SNL, Sandler’s specialty was mostly mentally challenged men who act like children and speak in odd voices, like Canteen Boy, Cajun Man, and the Herlihy Boy. Since leaving SNL, Sandler has had a lucrative movie career playing adult males suffering from arrested development in comedies like Billy Madison (1995), The Waterboy (1998), and Big Daddy (1999). But on the show, Sandler was at his best when he was singing the news headlines as “Opera Man” on Weekend Update or original holiday songs like “The Thanksgiving Song” (18.7), “Santa Don’t Like Bad Boys” (19.9), and “The Chanukah Song” (20.7). As for the others, all but Chris Farley, a fearless physical comedian with improvisational experience, were stand-up comedians, so there was a learning curve before they seemed entirely comfortable doing sketch comedy. Chris Rock used his voice as a stand-up comic to create his most popular recurring character, an angry black talk show host named Nate X. David Spade raised the bar on snide humor as the receptionist at Dick Clark Productions, a flight attendant on Bastard Airlines, and an entertainment reporter doing “The Hollywood Minute.” Rob Schneider took the longest to stand out, though his character, Richard Laymer, introduced one of the most popular SNL catchphrases of the 1990s (“Makin’ copies.”).

Their humor was not sophisticated, but then again it wasn’t trying to be, though at times it was too crass and sophomoric for SNL. In December 1993, New Yorker magazine James Wolcott wrote a scathing review of the show, accusing each cast member of being “issued a single shtick, which he or she beats to death”: David Spade (“practices nasal one-upmanship”), Adam Sandler (“does the annoying Opera Man”), Rob Schneider (“never broadened beyond his copy-machine kibbitzer”), and Chris Farley (“the most overindulged one-note”). “As for the women in the cast,” Wolcott quipped, “they could stage a work stoppage and who would know?”

Wolcott was right about the female cast members. In season 16 (1990–1991), there were three women in the cast (Hooks, Sweeney, and Victoria Jackson). After Hooks’s departure at the end of season 16, Jackson and Sweeney were joined by four new female featured players: Beth Cahill and Siobhan Fallon, who both lasted only one season; Melanie Hutsell; and Ellen Cleghorne, bringing the total number of cast members to an all-time high of eighteen. At the time of Wolcott’s review (during season 19), there were four women—Cleghorne, Hutsell, Sweeney, and newcomer Sarah Silverman—and twelve men.

Consequently, between seasons 16 and 20, the majority of recurring characters were male. By comparison, you can count the number of prominent recurring female characters during that time on a six-fingered hand: Zoraida the NBC Page and Queen Shenequa (both played by Ellen Cleghorne), Jan Brady (Melanie Hutsell), and the three sisters of Delta Delta Delta (Hutsell, Siobhan Fallon, Beth Cahill). Then there’s androgynous Pat (Julia Sweeney), who falls somewhere in the middle, raising the count to six and a half.

Allegations that Saturday Night Live is a “boy’s club” were nothing new, but the show was certainly low on estrogen. Between the years 1985 and 1990, the male-to-female cast member ratio was 3:1. In a February 1992 piece for the New York Times entitled “Women in the Locker Room at Saturday Night Live,” Eve Kahn addressed SNL’s gender politics both behind and in front of the camera. Lorne Michaels admitted that in trying to replace Jan Hooks, he got carried away when he hired four women who are all different types at the same time, calling it an “accident” (was it an “accident” that he added six guys in 1990 to a cast that already had five male regulars and two male featured players?). He also makes the point that he would not run a woman’s sketch for its own sake. “If it’s not funny,” he explains, “it doesn’t matter if it’s well intentioned.” But according to Kahn, the reality is that the female cast members get less airtime, which is why “all the new women are now frantically trying to write skits for themselves . . . but for the moment, they still appear only briefly on each show, and they may never dominate skits, the way the tenured male comics—Phil Hartman, Kevin Nealon, Dana Carvey—do.”

Whatever they were doing seemed to be working. In December 1992, Entertainment Weekly named the cast of Saturday Night Live “Entertainers of the Year.” “In its 18th year,” Mark Harris wrote, “Saturday Night Live has, with the buoyant rudeness that made its reputation in 1975, reclaimed its status as the show of the moment, and refashioned itself as something big enough to embrace both Wayne’s World and Wayne’s parents.” Harris cites the mixture of political and celebrity impersonations, which he says “coexist, immortalized in mockery, along some slightly less real but no less famous names” like Wayne and Garth, Hans and Franz, Dieter, Nat X, Mr. Subliminal, etc. In addition, there were some surprises over the past few years, like a visit by none other than Barbra Joan Streisand to Coffee Talk (17.14), and the ending of Sinéad O’Connor’s rendition of “War” in which she tore up the pope’s picture (18.2) (see chapter 16).

Two years after praising the show and its cast, a headline in Entertainment Weekly posed this question: “Is Saturday Night Dead?” The March 1994 article by Bruce Fretts offered SNL “20 helpful ideas” in honor of the show’s upcoming twentieth anniversary. The list of complaints and personal attacks sounded like something David Spade would read in his “Hollywood Minute” segment (as Spade would say, “It’s called backlash. Get used to it.”). In fact, Spade is the subject of their first suggestion, which is to have him replace Kevin Nealon because he “could bring the same snide sensibility to current events that he does to showbiz.” Other suggestions that made the list were to retire the Gap girls (Farley, Sandler, and Spade in drag) because the women on the show have “little to do,” produce new commercial parodies each week (and stop rerunning the same ones over and over), stop booking athletes as hosts, book hipper musical guests, teach cast member Melanie Hutsell a new facial expression, and tell Chris Farley to keep his shirt on.

So what happened between December 1992 and March 1994 that prompted Entertainment Weekly to do a complete 180° about Saturday Night Live? Answer: season 19 (1993–1994), which according Doug Hill was “generally considered” by the critics to be “a disaster.” Hill wrote an extensive piece for the New York Times at the start of season 20 that tried to put what was going on with the show in perspective and some of the possible causes for the decline in the ratings last season. The list included the loss of five veteran writers, which left head writer Jim Downey with “a nervous group of neophytes on both sides of the camera”; behind-the-scenes tension and “internal feuds” involving writers, production staff, and cast members; and interference by top brass at NBC, who Lorne Michaels characterized as a “much more activist management.” Although changes had been made, including the addition of seasoned comedic performers, like Chris Elliott, Michael McKean, and Kids in the Hall’s Mark McKinney, the criticism launched against the show only continued with reviews that featured headlines like “After Two Decades, How Much Longer?” (John J. O’Connor, New York Times), “Dear Saturday Night Live: It’s Over. Please Die.” (Rich Marin, Newsweek), and “Saturday Night Moribund” (Craig Tomashoff, People). One major loss to the show was the departure of the beloved Phil Hartman, whose impersonation of President Bill Clinton was prominently featured at the end of season 19. Darrell Hammond would eventually fill that gap when he joined the cast in season 21.

The negative press just kept coming, and Warren Littlefield, president of NBC Entertainment, was not helping by publicly criticizing the show. On March 8, 1995, Littlefield told Bill Carter on the record in a New York Times story that some of the “major changes” suggested by the network were “accomplished” but “there are a lot of things left undone.” He added that there was no question the show needed “sharper writing and a new batch of stars” and that “both those areas are being addressed.” Carter pointed out that it was not a decline in ratings that caused NBC to make changes in the show, which was still making money for the network. Although the show had reach a 9 rating in the 1992–1993 season, the current (1994–1995) 7.6 rating is the same as it was back in 1990–1991 (at the time, one rating point equaled 954,000 households). Also adding fuel to the fire that same month was a devastating thirteen-page cover story in New York magazine by Chris Smith entitled “Comedy Isn’t Funny: Saturday Night Live at Twenty—How the Show That Transformed TV Became a Grim Joke.” Smith spent a significant amount of time behind the scenes, observing and talking to the cast and writers. The article captures the turbulence, dysfunction, and discontent that permeated the seventeenth floor of 30 Rock. Some of the people Smith spoke to were not identified by name. One new cast member, Janeane Garofalo, was unhappy with the fraternity atmosphere and the limited roles she was getting to the point that she got out of her contract to go do a movie. The article ends with Garofalo waving goodbye during the “good nights” on her final show (20.14).

Memorable Characters and Sketches (Seasons 16–20)

Simon (16.5)

Simon (Mike Myers) is the British boy who hosts his own show on BBC 1 from his bathtub. He’s neglected by his father, with whom he travels, and lives in hotels because his mummy is “living with the angels” (16.5). He likes to do “drawerings” and shares them with us—but you better not look at his bum, “you cheeky monkey.” Sometimes he has other children in the tub with him whose fathers work for the same big American company: Trevor (Macaulay Culkin) (17.7), who shares his cowboy drawings; Vinnie Esposito (Danny DeVito) (18.10), a crude little Italian lad (“Where you lookin’ at my ass?”); and Kelly Clayton (Sara Gilbert) (19.11), whose mother is dating Simon’s father.

The Dark Side with Nat X (16.5)

The Dark Side with Nat X: “The only show on TV written by a brother, produced by a brother, and starring a brother [played by Chris Rock]!”

Live from Compton, California, Nat X (Chris Rock) is a militant African American with a large afro and the only 15-minute show on TV “because the man would never give a brother like me a whole half-hour!” He gives his top five list (reasons why white people can’t dance) and insults his white guests like Vanilla Ice (Kevin Bacon) (16.12), and then has his sidekick Sandman (Chris Farley) sweep them off the stage with a broom.

Bill Swerski’s Super Fans (16.10)

Bill Swerski’s Super Fans is a television show broadcast from Ditka’s Restaurant in Chicago, Illinois, home of a “certain football team, which has carved out a special place in the pantheon of professional football greats. . . . Da Bears!” In the first of five sketches, which aired in the 1990–1991 season (16.10), Bill Swerski is played by Chicago native Joe Mantegna, though in subsequent sketches his brother Bob (George Wendt) has taken his place due to Bill’s heart attack. Bill/Bob are joined by fellow Chicago Bears fans Todd O’Connor (Chris Farley), Pat Arnold (Mike Myers), and Carl Wollarski (Robert Smigel), who wear dark glasses and have mustaches—just like Coach Mike Ditka. They sit around drinking beer and eating sausage and predicting the score of the next game. Depending on the time of year, they also discuss Chicago’s other team—“Da Bulls!” In September 1991, they are joined by host Michael Jordan (17.1), who gives a short on-air plug for “The Michael Jordan Foundation.” (See also chapter 21.)

Richard Laymer, a.k.a. the Richmeister (16.11)

“Makin’ copies!”: Richard Laymer (Rob Schneider), a.k.a. the Richmester, has a front-row seat to the office photocopier.

Richard Laymer (Rob Schneider) is the annoying guy in the office near the photocopier who likes to give his coworkers nicknames every time they walk by and narrate what they were doing (“makin’ copies”) (“Steve-ster, Steve-man, Sandy the Sandstress,” “The Great Randino”). At one point, the copier has to be taken away (16.12), and his coworkers (Phil Hartman and Julia Sweeney) are concerned about the Richardmeister, who moves the coffeepot over to his desk. We also learn via a flashback that Richard (Macaulay Culkin) has been doing this since grade school when his desk was next to the pencil sharpener (17.7). In later sketches we see Richard in other office locations, such as L.A. Law’s (1986–1994) McKenzie, Brackman, Chaney, and Kuzak (17.12), and on the Branch Davidian Compound (18.15) where David Koresh (the “Christ-meister”) is “makin’ copies.” (See also chapter 21.)

Daily Affirmation with Stuart Smalley (16.12)

The television host Stuart Smalley (Al Franken) is introduced as a “caring nurturer, but not a licensed therapist” though he seems a little more focused on himself and his own issues than other people (his mantra is “I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggonit, people like me”). He does try to help a couple, John and Lorena B. [Bobbitt] (Rosie O’Donnell and Mike Myers) (19.6), who have filed for divorce, to share their feelings (Smalley gets her to apologize for cutting off his penis). He also shows viewers the meaning of true love when he chats with a pair of newlyweds, Michael J. [Jackson] and Lisa Marie P. [Presley] (Tim Meadows and Marisa Tomei), who can’t keep their hands off one another. (See also chapters 21 and 23.)

Chippendales Audition (16.14)

Chris Farley blew the needle off the laugh meter in this sketch in which he competes with Patrick Swayze to be a Chippendales dancer. Before they get started, the head judge (Kevin Nealon) tells them that either of them would make a wonderful addition to the Chippendales family. The music, Loverboy’s “Working for the Weekend,” begins. The handsome and lean Adrian (Swayze, a former dancer) has all the right moves. Barney (Farley) also has the moves, but when he takes off his shirt, he reveals his large belly. In the end, Nealon explains that the job goes to Adrian because Barney’s body is “fat and flabby.”

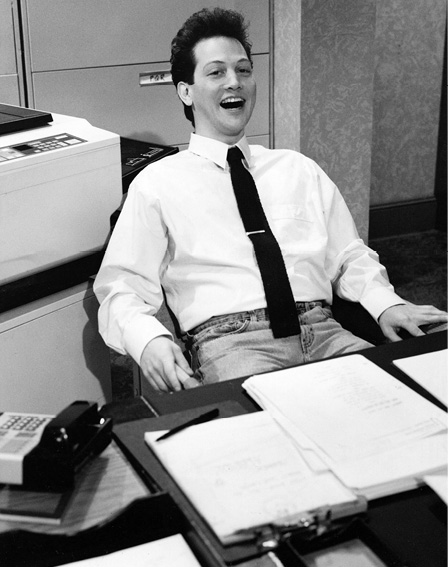

In one of his most memorable sketches on the show, Chris Farley (right) squares off with guest Patrick Swayze during a Chippendales audition (16.4).

According to Farley’s biography, The Chris Farley Show, SNL writers and cast members had mixed reactions to the sketch, ranging from “fantastic” to “lame” and “mean.” The sketch, written by Jim Downey, appeared in Farley’s fourth show. In the same biography, Downey recalled giving Farley the note that what’s important here is that he is not at all embarrassed when he’s told by the judge that the audience prefers a “more sculpted, lean physique as opposed to a fat, flabby one.” Whatever you may think about it, the sketch was definitely a turning point in Farley’s career. One of his agents, Doug Robinson, recalled that the sketch was key to getting the other agents at CAA to sign him as a client. “All we had to do was show everyone a video of the ‘Chippendales’ sketch, and it was done,” Robinson explained, “We signed him right then.”

The Chris Farley Show (17.2)

On a rare occasion, Chris Farley got the chance to play a character who was not loud and overbearing. In this case it was himself as the host of his own talk show. Only he wasn’t very good at asking his guests Jeff Daniels (17.2), Martin Scorsese (17.6), and Paul McCartney (18.13) questions. All he could think of to ask Sir Paul is, “You remember when you were with the Beatles . . . that was awesome.” When he brings up McCartney’s recent arrest in Japan for pot possession, Paul says he would like to forget all that. Farley reacts by hitting himself and saying, “Idiot! That’s so stupid! What a dumb question.” It was a pleasure just to watch Farley sit still in a chair for five minutes and demonstrate his skill as a comedian with great timing. The name of the sketch was used as the title of Farley’s biography by his older brother Tom and Tanner Colby. Head writer Jim Downey remembered the idea came from Farley himself, a “comedy nerd,” who would ask him about old sketches and essentially recite the entire thing for him. “Yes, Chris,” Downey would ask, “What about it?” “That was awesome,” Farley replied.

Coffee Talk with Linda Richman (17.3)

Modeled after his first wife’s mother, Linda Richman (Mike Myers) was a middle-aged Jewish woman, complete with Liz Taylor hair and large eyeglasses, who spoke in a heavy New York accent. She occasionally threw in a Yiddish word (or a word that was close enough), her favorite being “I’m a little verklempt” (verklempt means choked up or speechless). At that point she usually threw out a topic for her viewers to discuss, like “The New Deal was neither new nor was it a deal” or “The chickpea is neither a chick nor a pea.” But her favorite discussion topic was Barbra Streisand, who made a surprise appearance on the show (17.14). Richman loved The Prince of Tides (1991) and Streisand’s nails, which were “like buttah.” Myers also did an impersonation of Streisand on SNL in a parody of President Clinton’s Inaugural Gala (18.11) and as one of the many performers who records a duet with Frank Sinatra (Phil Hartman) (19.6).

Dick Clark Productions Receptionist (17.8)

This simple sketch lets David Spade do what he does best: be snide and condescending, cut people off mid-sentence, and then tell them to “take a seat.” He has no idea who rapper Hammer is, nor does he allow Kremlock, an alien from Planet Orton 5 (Dana Carvey), to see earthling Richard Clark so he can go on the “television airwaves to warn people of this planet of imminent doom and destruction” (17.8). He irritates Roseanne Arnold because he’s never heard of her or her show (“I only watch PBS.”), tells a women claiming to be Clark’s long-lost biological mother (Julia Sweeney) to “be a dove” and keep the area clear in front of his desk, and doesn’t recognize Jesus Christ—from the Bible (“I’m not a big reader. If you could just have a seat.”) (17.14). The last time we see Spade as the receptionist he’s working for the chief of the Los Angeles Fire Department during the Malibu fires (19.6), which gives him the chance to pull the same attitude on celebrities like Charlton Heston (Phil Hartman), Sean Penn (Jay Mohr), Penny Marshall (Rosie O’Donnell), and Marla Gibbs (Ellen Cleghorne), who are all desperately trying to get past his desk to see their ravaged homes.

“Tonight Song,” Sung by Steve Martin and Cast (17.9)

Backstage before the show, Chris Farley shows Steve Martin his old King Tut costume, which makes the host realize that back then he used to care—when the show meant something. And that’s his cue to launch into one of the more elaborate opening numbers sung by Martin and the season’s sixteen cast members in which they all vow to do their best tonight.

Debate ’92: The Challenge to Avoid Saying Something Stupid (18.3)

The three contenders for the Democratic nomination in the 1992 presidential election—former California governor Jerry Brown (a.k.a. Governor “Moonbeam,” a nickname given to him by onetime-girlfriend singer Linda Ronstadt); former U.S. Senator from Massachusetts Paul Tsongas; and governor of Arkansas Bill Clinton—were not high-profile candidates. The public knew little about them, which accounts for their SNL debut in a cold opening in March 1992 (17.15), in which all three candidates (Dana Carvey as Brown, Al Franken as Tsongas, and Phil Hartman as Clinton) address a Star Trek convention as part of C-SPAN’s coverage of “Road to the White House.” Once Clinton is declared the Democratic nominee, he joins a three-way debate between incumbent President George H. W. Bush and the independent candidate, a short, bossy Texas billionaire named Ross Perot. Dana Carvey, who had spent the last four years perfecting his George H. W., is forced to do double-duty and impersonate the diminutive Perot. In the first presidential debate, which SNL dubs “Debate ’92: The Challenge to Avoid Saying Something Stupid,” Carvey plays both Bush and Perot, whose answers to questions were previously recorded. At one point Perot led the polls, but his popularity stalled due to a variety of factors, including his decision to exit and then reenter the election and his questionable campaign tactics. With his small size, heavy Texan accent, and bigger-than-life personality, he was the ideal target for parody. After the poor performance of his running mate, Vice Admiral James Stockdale, a highly decorated, navy hero and former Vietnam POW, in the vice-presidential debate, Perot tries to ditch him on a country road (18.4). Stockdale, who was unprepared to be a political candidate, is portrayed by Phil Hartman as a shell-shocked old man.

Clinton Visits McDonald’s (18.8)

On the same episode that opened with a Wayne’s World sketch in which derogatory remarks were made about First Daughter–elect Chelsea Clinton (for which Lorne Michaels and Mike Myers later apologized; see chapter 22), there was a funnier, less-than-flattering sketch about her father. President-elect Clinton (Phil Hartman) jogs about three blocks with the Secret Service in tow and makes a pit stop at McDonald’s. At the time, Clinton’s bad eating habits were no secret. He gained thirty pounds on the campaign trail, and, according to a December 1992 New York Times story, he made a “solemn vow” to eat right. Clinton starts to mingle with the people, and as he does, he begins to eat their food, even using it as props to explain his position on sending troops to Somalia. He even gets an Egg McMuffin on the house (and puts barbecue sauce on it). When Hartman exited SNL at the end of the 1993–1994 season, he left the show without a Clinton impersonator. The following season opens (20.1) with cast members Chris Farley, Chris Elliott, David Spade, and Tim Meadows auditioning to be the show’s new Bill Clinton (they all get rejected). Consequently, the president was MIA during season 20, though new cast member Michael McKean impersonated him for two sketches in which he outlines his health care bill (20.2) and delivers his Christmas message with Mrs. Clinton (Janeane Garofalo). In the following season, Darrell Hammond takes over the role for the remainder of Clinton’s years in the White House.

Matt Foley, Motivational Speaker (18.19)

Happy Mother’s Day!: The season 17 cast members and their moms celebrated the day in style in a prime-time special that aired on Sunday, May 10, 1992.

A popular character on SNL in the early 1990s, Matt Foley (Chris Farley) was developed on the Second City stage in Chicago by Chris Farley and writer Bob Odenkirk. According to Farley’s biography, The Chris Farley Show, he was named after a classmate at Marquette University who became a priest. Farley’s Foley is a big, loud, overbearing, hyperactive motivational speaker who tells his audience about the harsh realities of life, including his own, which is meant to serve as a warning that if they don’t wise up, they might end up like him: “35 years old, eating a steady diet of government cheese, thrice divorced, and living in a van down by the river!” It doesn’t matter if the people he’s talking to are young or old or if someone has a great life and/or a successful career—he will mock them and tell them to shut up. In the process he throws his large frame around, sometimes breaking furniture in the process.

In his first appearance (18.19), concerned parents (Phil Hartman, Julia Sweeney) hire Foley to talk to their kids (David Spade, Christina Applegate) after they find a large bag of weed in the family room. Foley was downstairs in the basement drinking coffee for four hours before he comes upstairs and starts going off on the kids, during which both Spade and Applegate can barely contain themselves. In later episodes he’s hired to straighten out Halloween pranksters (19.5), works as a motivational Santa in a mall and tells kids there is no Santa Claus (19.9), and speaks to juvenile delinquents in a Scared Straight program (19.14). When Farley returned to host the show in October 1997, Foley made his last appearance (23.4), in which he is working for a fitness instructor to motivate his spinning class and, in the process, destroys the bike he’s using for a demonstration.

“So Long, Farewell” to Phil Hartman (19.20)

On the final show of season 19, the entire cast bid the audience adieu by singing Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “So Long, Farewell” from The Sound of Music with most of the cast dressed as their recurring characters (Mike Myers as Linda Richman, Julia Sweeney as Pat, etc.). At the end of the song, Hartman sits down on the stage next to a sleepy Chris Farley (dressed as Matt Foley) and puts his arm around him and says, “I can’t imagine a more dignified way . . . to end my eight years on this program.” In retrospect, seeing the two of them together in that final moment is touching and very sad as both of them died within the next four years—Chris Farley in 1997 at the age of thirty-three and Phil Hartman in the following year at the age of forty-nine.

During his final week on the show, the much beloved Hartman was given a bronze stick of glue because his castmates considered him “the glue” of the show.