23

From the Small Screen to the Big Screen

SNL Goes to Hollywood

Since the 1950s, Hollywood has been turning television series into motion pictures with limited success. For every M*A*S*H (1972–1983), Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997–2003), and Friday Night Lights (2006–2011), there are countless unsold pilots and bomb television shows based on popular films. There is simply no guarantee a television series based on a classic Hollywood movie, a box-office hit, or a cult film will garner high ratings, particularly if you subtract one of the major elements that contributed to its popularity. Who wants to see a TV version of Casablanca (1983) starring David Soul in the Humphrey Bogart role? Or Ferris Bueller (1990) without Matthew Broderick? Or Delta House (1979), the short-lived TV version of the box-office hit Animal House (1978), minus John Belushi?

The reverse is also true. Some television series simply don’t translate to the big screen. The ones that do score at the box office (and, in some instances, with the critics), like The Addams Family (1991), Get Smart (2008), and the Mission Impossible (1996) and Star Trek (1979–2013) franchises, are updated and/or retooled to broaden their appeal to contemporary audiences. Still, that doesn’t stop some studio executives from overestimating the ticket-buying public’s interest in certain old television shows and “greenlighting” television-to-film adaptations, which is exactly what happened with the film versions of Car 54, Where Are You? (1994), My Favorite Martian (1999), The Mod Squad (1999), The Honeymooners (2005), and Land of the Lost (2009).

The adaptation of a comedy sketch with one or more recurring characters into a feature-length film poses even greater challenges. Recurring characters on sketch comedy shows are thinly drawn and certainly not as developed as sitcom characters because there simply isn’t time in a five- to eight-minute sketch. On SNL, the character(s) and comedic premise are introduced in the first sketch, so by the third or fourth sketch the audience’s expectations are firmly established, which is why recurring sketches are fueled by repetition.

When it’s time for characters to make the leap to the big screen, screenwriters face the difficult task of expanding a five- to eight-minute sketch into a ninety-minute film. In most instances, a backstory is developed for the main characters, additional characters are added into the mix, and the characters’ “universe” is expanded beyond the sketch’s main setting. The audience sees where Pat Riley lives, discovers what the Roxbury Guys do during their daylight hours, and meets Mary Katherine Gallagher’s guardian, who was mentioned but never shown on SNL.

All of the following films feature characters that first appeared on SNL. With the exception of the two Blues Brothers films and It’s Pat: The Movie (1994), they were all produced by Lorne Michaels. Most of the films were released in the 1990s, beginning with the box-office hit Wayne’s World (1992), though none of the subsequent films came close to repeating its success. As the list below illustrates, few of the SNL films turned a substantial profit if any at all, and two in particular—It’s Pat and Stuart Saves His Family (1995)—were major financial disasters.

|

SNL Sketch Films (1980–2010) |

Budget/Box Office (worldwide) |

|

Gilda Live (1980) |

None/$2.2 million |

|

The Blues Brothers (1980) |

$27.5 million/$115.2 million |

|

Wayne’s World (1992) |

$20 million/$183 million |

|

Coneheads (1993) |

$33 million/$21.1 million |

|

Wayne’s World 2 (1993) |

$40 million/$48.1 million |

|

It’s Pat (1994) |

$8 million/$60,822 |

|

Stuart Saves His Family (1995) |

$6.3 million/$912,082 |

|

The Blues Brothers 2000 (1998) |

$28 million/$14 million |

|

A Night at the Roxbury (1998) |

$17 million/$30.3 million |

|

Superstar (1999) |

$34 million/$30.6 million |

|

The Ladies Man (2000) |

$24 million/$13.7 million |

|

MacGruber (2010) |

$10 million/$9.3 million |

The Blues Brothers (1980): “They never got caught. They are on a mission from God.”

Directed by John Landis. Written by Dan Aykroyd and John Landis. Producer: Robert K. Weiss. Executive Producer: Bernie Brillstein. Cinematography: Stephen M. Katz. Editor: George Folsey Jr.

Cast: John Belushi (Jake Blues), Dan Aykroyd (Elwood Blues), James Brown (Reverend Cleophus James), Cab Calloway (Curtis), Ray Charles (Ray), Aretha Franklin (Mrs. Murphy, Carrie Fisher (Mystery Woman), Henry Gibson (Head Nazi), John Freeman (Burton Mercer), Kathleen Freeman (Sister Mary Stigmata), Steve Lawrence (Maury Sline), Twiggy (Chic Lady), Frank Oz (Corrections Officer), Judith Jacklin (Cocktail Waitress), Rosie Shuster (Cocktail Waitress), Steven Spielberg (Cook County Assessor’s Office Clerk).

Distributed by Universal. Running time: 133 mins. Rated R.

The Blues Brothers 2000 (1998): “The Blues Are Back.”

Directed by John Landis. Written by Dan Aykroyd and John Landis. Producers: Dan Aykroyd, Leslie Belzberg, and John Landis. Cinematography: David Herrington. Editor: Dale Beldin. Original Music: Paul Shaffer.

Cast: Dan Aykroyd (Elwood Blues), John Goodman (Mighty Mack McTeer), Kathleen Freeman (Mother Mary Stigmata), B. B. King (Malvern Gasperon), Nia Peeples (Lt. Elizondo), Aretha Franklin (Mrs. Murphy), Steve Lawrence (Maury Sline), Darrell Hammond (Robertson), Paul Shaffer (Marco), James Brown (Cleophus James).

Distributed by Universal. Running time: 123 mins. Rated PG-13.

The Blues Brothers—“Joliet” Jake (John Belushi) and Elwood (Dan Aykroyd)—made their first of three appearances on SNL on January 17, 1976 (1.10). Host Buck Henry introduced them as “Howard Shore and the All-Bee Band,” and instead of their signature black suits, white shirts, and skinny black ties, Jake and Elwood, along with the rest of the band, wore bee costumes, which was part of a running gag in season 1 (bandleader Shore was dressed as a beekeeper). Jake sang “I’m a King Bee,” a swamp blues song written and first recorded by Slim Harpo, accompanied by Elwood on the harmonica. At the time, viewers didn’t know what they were watching was not just another SNL Bee gag, or even a gag at all, but the birth of a legitimate revivalist rhythm and blues band. This was also not their first public performance. They had played around New York City and warmed up SNL audiences before the show. More importantly, Belushi and Aykroyd did not think of themselves as actors playing characters as one does in a sketch. Their alter egos, Elwood and Jake, were serious blues men, and their band included members of the SNL house band along with other recruits, all of whom appear in the film under their real names.

Over the next four years, the Blues Brothers’ debut album, Briefcase Full of Blues (1978), would go double platinum, reaching #1 on the Billboard 200 in January 1979. During that time, the Brothers appeared twice on SNL (minus the bee costumes). On April 22, 1978, they were the musical guests with host Steve Martin (3.18), for whom they opened at the Universal Amphitheatre. They returned on November 18, 1978, with host Carrie Fisher (4.6), who also appears in the film, and opened the show with “Soul Man,” which reached #14 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. In the summer of 1980, Universal Studios released The Blues Brothers, a big-budget screen comedy that reunited Belushi with National Lampoon’s Animal House director John Landis.

In the thinly plotted film, Jake and Elwood try to raise the $5,000 that’s needed to prevent the foreclosure of the Catholic orphanage where they were raised. They manage to reassemble their old band, but their first gig, for which they pose as a country-western band, the Good Ol’ Boys, is a bust. They blackmail their old booking agent to get them a gig at the Palace Hotel Ballroom, where a record executive comes backstage and offers them an advance for a recording contract. With the money they need, the brothers rush to the assessor’s office in downtown Chicago to pay the tax bill and save the orphanage.

The Blues Brothers is part musical, part action comedy, though most of the film’s 133 minutes are devoted to car chases and crashes shot in and around Chicago. Some of the stunts are impressive, such as when Jake and Elwood’s car, an old police car dubbed the Bluesmobile, jumps the 95th Street drawbridge. But the car chases, particularly a long sequence inside a shopping mall, and the resulting car crashes and pileups are excessive, and by the second hour, repetitive.

The action sequences were a successful strategy to attract young ticket buyers who Aykroyd, Belushi, and Landis probably assumed have little or no interest in what The Blues Brothers was really selling—rhythm and blues music. The film’s real high points are the musical performances by living legends James Brown, Cab Calloway, Ray Charles, and Aretha Franklin, who, in between all the chases and wreckage, get to do their thing.

According to a 2013 Vanity Fair article by Ned Zeman chronicling the making of the film (including Belushi’s heavy drug use that reportedly slowed the production down), Universal Pictures executives were not pleased with the film’s rising budget, which did not go unnoticed by the critics. Variety (6/18/80) called The Blues Brothers a “diverting, but not hilarious, farce [that] has enough to offer to draw sizable crowds but, as always with such inflated enterprises, extent of ultimate payoff is questionable.” For Time magazine’s Richard Corliss (7/7/80), “The most impressive thing about The Blues Brothers is its numbers: a budget in the $30 million–$38 million range, a cast of 91, a crew of 191, a stunt team of 78, and the cooperation of nearly every able-bodied Chicagoan except Dave Kingman [a slugger for the Chicago Cubs].” Roger Ebert, film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, was surprised how much he enjoyed what he described as “the Sherman tank of musicals . . . a big, raucous powerhouse that proves against all odds that if you’re loud enough, vulgar enough, and have enough raw energy, you can make a steamroller into a musical, and vice versa.”

The Blues Brothers didn’t die with John Belushi. The band continued to play and even did a world tour in 1988. Ten years later, they reunited for the film sequel, The Blues Brothers 2000, directed by John Landis, who once again cowrote the screenplay with Dan Aykroyd. Set eighteen years later, the film opens on a somber note. Elwood is released from prison and learns that his brother Jake is dead (the film is dedicated to the late John Belushi, John Candy, and Cab Calloway). Unfortunately, it rehashes the plot of the first film, with Jake reassembling the old band plus two new members—Mighty Mack McTeer (John Goodman) and an orphan, Buster Blues (J. Evan Bonifant). The action extends beyond Chicago’s city limits as the band heads to New Orleans with the police, white supremacists, and the Russian mafia on their tail. All roads lead to a mansion, the home of a voodoo queen (Erykah Badu), where the Blues Brothers participate in a battle of the bands against the “the Louisiana Gator Boys,” which includes an impressive lineup of musical greats like B. B. King, Eric Clapton, Clarence Clemons, Bo Diddley, Isaac Hayes, Billy Preston, Lou Rawls, and Steve Winwood. The film also features performances by Aretha Franklin and James Brown, reprising their roles from the first film.

The critics gave thumbs-up to the music, but found the film as a whole to be a “lame comedy” (Roger Ebert, 2/6/98), a “wildly uneven sequel” (Joe Leydon, Variety, 2/5/98), with a “disposable plot” (Lawrence Van Gelder, New York Times, 2/6/98).

Coneheads (1993): “Young ones! Parental units! We summon you!”

Directed by Steve Barron. Written by Tom Davis, Dan Aykroyd, Bonnie Turner, and Terry Turner. Producer: Lorne Michaels. Executive Producer: Michael I. Rachmil. Cinematography: Francis Kenny. Editor: Paul Trejo. Original Music: David Newman.

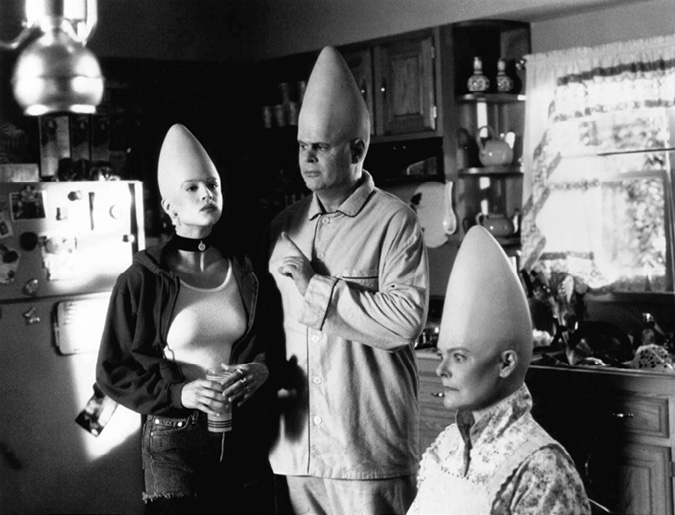

Connie (Michelle Burke, left), Beldar (Dan Aykroyd), and Prymaat (Jane Curtin) adapt to suburban life in Coneheads (1993).

Cast: Dan Aykroyd (Beldar Conehead/Donald R. DeCicco), Jane Curtin (Prymaat Conehead/Mary Margaret DeCicco), Michelle Burke (Connie Conehead), Laraine Newman (Laarta), Phil Hartman (Marlax), Chris Farley (Ronnie the Mechanic), Kevin Nealon (Senator), Jan Hooks (Gladys Johnson), Michael McKean (Gorman Seedling), Jason Alexander (Larry Farber), Lisa Jane Persky (Lisa Farber).

Distributed by Paramount Pictures. Running time: 109 mins. Rated PG.

Fourteen years after we first watched them from our “living chambers,” the Coneheads were the subject of a feature-length “celluloid fantasy” (that’s Conehead-speak for “film”). The screenplay was written by Coneheads creators Tom Davis and Dan Aykroyd, who cowrote the screenplay with Bonnie and Terry Turner, SNL writers and creators of the aliens-on-earth situation comedy 3rd Rock from the Sun (1996–2001) starring Jane Curtin. Coneheads recounts the story of Fuel Survey Underlord Beldar Clorhone (“Conehead” is the Americanized version of their last name) (Aykroyd); his wife, Prymaat (Curtin); and their teenage daughter, Conjaab (known as “Connie” on earth) (Michelle Burke) and their assimilation to suburban life on earth (Laraine Newman, who originated the part of Connie on SNL, has a cameo). All the while they are being pursued by an INS agent, Gorman Seedling (Michael McKean) and his equally sleazy assistant (David Spade). As in the sketches, the initial jokes revolve mostly around the Conehead family’s assimilation to suburban life on earth. The second half of the film is set on the planet Remulak, where Beldar is forced to fight a garthok, a fierce six-legged beast, to the death.

In addition to McKean and Spade, Coneheads doubles as an SNL cast reunion with Chris Farley in a featured role as Connie’s insecure lovestruck beau, Ronnie, and smaller bit parts played by former and current cast members including Phil Hartman, Jan Hooks, Tim Meadows, Jon Lovitz, Peter Aykroyd, Tom Davis, Garrett Morris, Kevin Nealon, Julia Sweeney, and Adam Sandler.

Critics were not impressed by the film. “Not much is really funny,” complained Roger Ebert. “The story is without purpose; there nothing for us to care about, even in a comedic way.” In her review for the New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote that the film “has its dopey charms,” but “falls flat about as often as it turns funny, and displays more amiability than style.” On a more positive note, Variety critic Leonard Klady called Coneheads “a sweet, funny anarchic pastiche that should find broad based popularity. Its sly combination of the outrageous and the mundane is surprisingly appealing screen entertainment that transcends the one-joke territory it inhabited on television.” But Klady was wrong. The film did not find “broad based popularity,” and the box-office returns were disappointing.

Gilda Live (1980): “Things like this only happen in the movies.”

Directed by Mike Nichols. Written by Anne Beatts, Lorne Michaels, Marilyn Suzanne Miller, Don Novello, Michael O’Donoghue, Gilda Radner, Paul Shaffer, Rosie Shuster, and Alan Zweibel. Producer: Lorne Michaels. Directors of Photography: Ted Churchill, James Contner, Alan Metzger, Peter Norman. Editors: Ellen Hovde, Lynzee Klingman, Muffie Meyer. Musical Director: Howard Shore. Musical Consultation: Paul Shaffer. Original Broadway production produced and directed by Lorne Michaels.

Cast: Gilda Radner (various characters), Don Novello (Father Guido Sarducci), Rouge (Diana Grasselli, Myriam Valle, Maria Vidal), Paul Shaffer (Don Kirshner/The Candy Slice Group), Howard Shore (The Candy Slice Group).

Distributed by Warner Bros. Running time: 90 mins. Rated R.

In 1979, between seasons 4 and 5 of SNL, Gilda Radner spent her summer vacation onstage at the Winter Garden Theatre, where she starred in her own Broadway musical comedy revue, Gilda Radner—Live from New York. Produced and directed by Lorne Michaels and written by Radner and members of the SNL writing staff, Radner entertained New York audiences with a mixture of songs and sketches. Gilda Live, a film version of the concert, was released the following year.

The film, directed by Mike Nichols, is like watching a “Best of Gilda Radner” DVD. All of the characters that made Radner a household name are showcased in this ninety-minute stage show filmed in front of a live audience. Roseanne Roseannadanna gives the commencement speech at the Columbia School of Journalism. Emily Litella is substituting at P.S. 164 in Bedford-Stuyvesant for a teacher recovering from his recent “stubbing” (stabbing). Little Judy Miller bounces around her bedroom as she entertains herself with “The Judy Miller Show.” At her piano recital, Lisa Loopner performs “The Way We Were” in honor of her idol, composer Marvin Hamlisch. Zonked-out punk rocker Candy Slice honors Mick Jagger with “Gimme Mick.” Former 1960s girl group Rhonda Weiss and the Rhondettes reunite to mourn the loss of a sugar substitute with “Goodbye, Saccharin” (which Radner sang on SNL in episode 2.16). Ironically, the film’s highlight is the closing number in which Gilda is just being herself. She sings “Honey (Touch Me with My Clothes On),” an original song she wrote with Paul Shaffer. In between we catch glimpses of Radner getting in and out of her costumes backstage and some comedic bits from Paul Shaffer (doing his Don Kirshner impression) and Father Guido Sarducci (Don Novello).

It’s all very familiar—and that’s the problem. Is it worth the price of a Broadway show admission (average cost back then was around $20) or a movie ticket to see someone perform in person or on film what you have been watching for free on television? The film critics agreed: Radner is funny and talented, but the material lacks the depth one expects for the stage or big screen. As Herald Examiner critic Michael Sragow points out, “What’s [sic] we miss most in “Gilda Live” is Gilda live . . . In the night-by-night, rehearsed revue format, the satire loses its spontaneity, its air of luck.” It’s also not surprising that many critics felt that as Father Guido Sarducci, Novello’s talents were better suited for the revue format because he is a solo performer, unlike some of Radner’s characters, like Roseannadanna, Litella, and Loopner, who are paired on SNL with other characters like Weekend Update cranky anchor Jane Curtin and Lisa’s equally nerdy boyfriend, Todd (Bill Murray).

Gilda Live may have been a critical and box-office failure—but Gilda’s fans are grateful that her performance has been preserved. Radner did return to Broadway in 1980 to star in Lunch Hour, a comedy written by Jean Kerr and directed by Mike Nichols.

It’s Pat: The Movie (1994): “A comedy that proves love is a many gendered thing.”

Directed by Adam Bernstein. Written by Jim Emerson, Stephen Hibbert, and Julia Sweeney. Based on characters by Julia Sweeney. Producer: Charles B. Wessler. Coproducers: Richard S. Wright and Cyrus Yavneh. Cinematography: Jeff Jur. Editor: Norman Hollyn. Original Music: Mark Mothersbaugh.

He or she? The question remains unanswered when the mystery known as Pat (Julia Sweeney) hits the big screen in It’s Pat (1994).

Cast: Julia Sweeney (Pat Riley), Dave Foley (Chris), Charles Rocket (Kyle Jacobsen), Kathy Griffin (Herself), Julie Hayden (Stacy Jacobsen), Kathy Najimy (Tippy), Camille Paglia (Herself), Tim Meadows (KVIB-FM Station Manager).

Distributed by Touchstone Pictures. Running time: 77 mins. Rated PG-13.

Born on the stage of the Groundlings Theatre in Los Angeles, the androgynous Pat Riley made his-her SNL debut in a graveyard sketch (the last sketch of the night) in December 1990 (16.7). Bill (Kevin Nealon) gets a new job in an office, but he can’t seem to figure out the gender of his new boss, Pat (Julia Sweeney). Donning a black wig, large framed glasses, mannish clothes, and a body suit that makes it impossible to determine what Pat has above or below the waist, Julia Sweeney’s androgynous creation only manages to add to the confusion whenever Bill or anyone else asks Pat a question that aims to figure out if Pat is a he or a she. Pat tells Bill his-her ex-fiancé is named “Chris.” By the next sketch (16.13), they’ve apparently reconciled because Pat introduces coworker Sue (Roseanne Barr) to Chris (Dana Carvey), another human question mark with long blonde hair who wears a purple silk shirt (or is it a blouse?) and pants. Pat’s coworkers even resort to playing strip poker—but Pat doesn’t lose a hand (17.10). At one point it seemed our questions would finally be answered when Pat joins a health club and has to enter the locker room. At that very moment, the sketch is interrupted by Weekend Update anchor Kevin Nealon with breaking news (17.6). In later sketches, Pat appears in parodies of Basic Instinct (17.17), Single White Female (18.3) (the ad for a roommate reads “Single White Person”), and The Crying Game (18.16), featuring the film’s stars, Miranda Richardson and Stephen Rea. In the final sketch, he-she is about to reveal his-her gender, but an audience member, played by Adam Sandler, pleads with Pat not to reveal the truth (18.11).

As in the sketches, there is a character in It’s Pat: The Movie, a neighbor named Kyle (SNL alum Charles Rocket), who is trying to solve the mystery surrounding Pat’s true gender. Kyle’s quest turns into an obsession to the point that he starts stalking Pat and invading his-her privacy. Of course, the mystery is never solved. But the film’s central plotline focuses on Pat’s personal problems surrounding his-her inability to hold a job and choose a career, which affects his-her relationship with Chris. What’s surprising about the film is how screenwriters Sweeney, Stephen Hibbert, and Jim Emerson made Pat into such an unlikable character. In an interview with Variety in 1999, Sweeney explained the origins of Pat: “We all had someone that’s like Pat: it has nothing to do with gender. It’s just someone who’s annoying, who’s oblivious, who’s always getting in people’s way.” But does an audience want to spend 77 minutes with a character who is designed to be annoying? More importantly, the film seems to be a missed opportunity—it could have used the character of Pat to make a larger statement about sexual and gender-related issues, such as stereotyping or the acceptance of differences. Instead, it’s just silly.

Disney clearly didn’t have any faith in the film. It’s Pat was released in “limited regional engagements” (three cities, actually) and grossed around $60,000. The critics used adjectives like “shockingly unfunny” (Variety) and “truly terrible” (Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times). It’s Pat received five Razzie nominations, but thankfully didn’t take home any awards, losing to bad films seen by more people, like Showgirls (1995) and The Scarlet Letter (1995).

The Ladies Man (2000): “He’s cool. He’s clean. He’s a love machine.”

Directed by Reginald Hudlin. Written by Tim Meadows, Dennis McNicholas, and Andrew Steele. Producer: Lorne Michaels. Executive Producers: Erin Fraser, Thomas Levine, Robert K. Weiss. Cinematography: Johnny E. Jensen. Editor: Earl Watson. Original Music: Marcus Miller.

Cast: Tim Meadows (Leon Phelps), Karyn Parsons (Julie Simmons), Billy Dee Williams (Lester), John Witherspoon (Scrap Iron), Jilly Talley (Candy), Lee Evans (Barney), Will Ferrell (Lance DeLune), Sofia Milos (Cheryl), Eugene Levy (Bucky Kent), Julianne Moore (Audrey), Tiffani Thiessen (Honey DeLune), Rocky Carroll (Cyrus Cunningham), Chris Parnell (Phil Swanson), Mark McKinney (Mr. White).

Distributed by Paramount Pictures. Release date: October 13, 2000.

Leon Phelps (Tim Meadows), better known as “The Ladies Man,” was a popular SNL character that made frequent appearances between 1997 and 2000. Phelps hosts his own call-in television show in which he dispenses advice about love, sex, and the art of seduction. But like his waterbed and scented candles, the bottle of Courvoisier cognac he keeps nearby, his oversized Afro, and his affinity for 1970s fashion (tight pants, polyester shirt, and leather vest), Phelps’s sexist attitude toward women is outdated. According to the press notes for the film, Meadows modeled Leon on the kind of men he encountered as a teenager while working in a Detroit liquor store: “They were the sort of guys who played the lottery every day and always wore outfits which, though they were cheap, were completely matching. . . . None of these guys had girlfriends, but they had lots of women, and they thought they were pretty cool.”

Phelps occasionally featured women on his show, like local actresses Deborah Hogan (Julianne Moore, who has a cameo in the film), who helps him demonstrate how to sweet talk a lady (23.16), and Julie (Cameron Diaz) (24.1), who plays Monica Lewinsky opposite Leon’s Bill Clinton in a reenactment of their sexual encounter detailed in The Starr Report. The real Monica Lewinsky even joined Leon (24.18) and answered some of the callers’ questions. Based on her own experiences, she strongly advised against getting involved with people at work or telling other people, including your best friend, that you ever have phone sex.

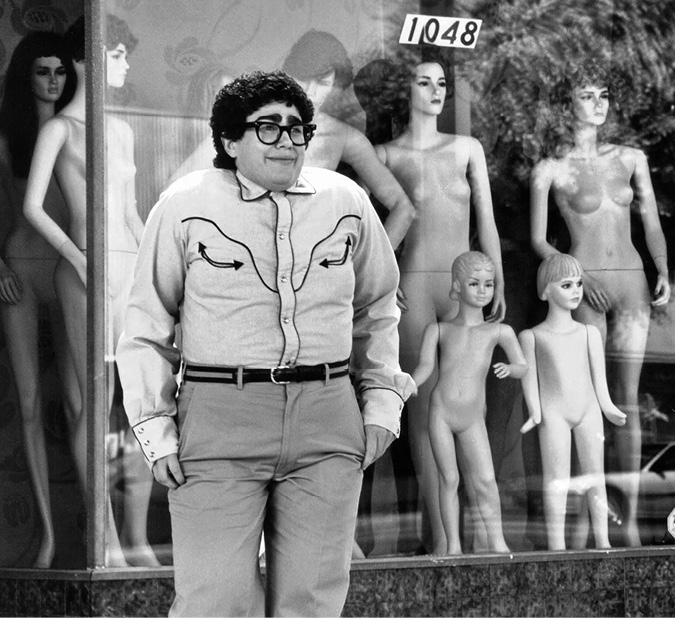

Leon Phelps (Tim Meadows) is the smooth-talking radio show host known as The Ladies Man (2000).

It’s not entirely clear why someone thought expanding the sketch into a feature-length film was a good idea. Like Pat Riley, Phelps is essentially a one-joke character in a one-joke sketch. When he’s not giving his listeners questionable advice, he’s bedding women—actually any woman who is willing and weighs under 250 pounds. There is something innocent about Phelps’s sexist ignorance, but it’s not enough to make him endearing, making it difficult to believe that his smart, good-natured producer and eventual romantic interest, Julie (Karyn Parsons), would remain loyal to him when he gets canned from a Chicago radio station.

The second plotline focuses on a band of desperate husbands whose wives all cheated on them with the same man. They spend the entire film trying to track down Phelps, and in the film’s climactic scene, the men, led by Lance DeLune (Will Ferrell), finally corner Phelps, which is his cue to show his human side and convince the men it’s all their fault that he slept with their wives. If they were more attentive husbands, their women would not have been going after him.

The critics were not amused. Roger Ebert gave it one star and called it “desperately unfunny.” New York Times critic A. O. Scott was kinder than Ebert, but only because Ladies Man is better than Stuart, Pat, Roxbury, and Superstar. Some other choice adjectives used by critics included “slapped-together” (Kirk Honeycutt, Hollywood Reporter) and “disconcertingly bland” (Robert Koehler, Variety). Boxofficemojo.com reported the film’s domestic and foreign total gross at $13.7 million, a little more than half its $24 million budget.

MacGruber (2010): “The Ultimate Tool.”

Directed by Jorma Taccone. Written by Will Forte, John Solomon, and Jorma Taccone. Producers: John Goldwyn and Lorne Michaels. Executive Producers: Erin David, Ryan Kavanaugh, Seth Meyers, Akiva Schaffer, Tucker Tooley. Coexecutive producers: Kenneth Halsband and Ben Silverman. Cinematography: Brandon Trost. Editor: Jamie Gross. Original Music: Matthew Compton.

Cast: Will Forte (MacGruber), Kristen Wiig (Vicki St. Elmo), Ryan Phillippe (Lt. Dixon Piper), Val Kilmer (Dieter Von Cunth), Powers Boothe (Col. James Faith), Maya Rudolph (Casey Fitzpatrick).

Distributed by Universal. Running time: 95 mins. Rated R.

MacGruber is a parody of the television series MacGyver (1985–1992), starring Richard Dean Anderson as Angus MacGyver, a low-key secret agent who refuses to carry a gun, choosing instead to defend himself by using his resourcefulness and knowledge of science. Between 2007 and 2010, Will Forte starred in nine shorts (usually shown in three parts over the course of an SNL episode) that basically revolve around the same plot. MacGruber and Casey (Maya Rudolph), who was later replaced by Kristen Wiig as Vicki, are in trouble, and he must beat the clock and defuse a bomb using a combination of objects, such as a paper clip, twine, a gum wrapper, and dog turd (32.11) or a paper cup, pine needles, and pubic hair (32.11). With only seconds left, MacGruber gets easily distracted by matters that seem trivial by comparison, like his receding hairline (33.2), the plummeting stock market (34.5), and his son Merrill’s (Shia LaBeouf) homosexual tendencies (33.11). MacGruber sketches were also used as part of a Pepsi campaign in a series of three commercials that aired during the January 31, 2009, episode of SNL. In the spots, which featured Forte, Wiig, and MacGyver’s Richard Dean Anderson, MacGruber has become a pitchman for Pepsi. In one ad, MacGyver accuses MacGruber of “selling out” (because if you acknowledge that you are doing so, maybe you won’t get criticized). Another ad, in which MacGruber changes his name to Pepsuber, aired during Super Bowl XLIII. Not since season 1, when host Candice Bergen and cast members did live commercials for Polaroid, has SNL been in partnership with Madison Avenue. Commercial parodies are a hallmark of SNL’s special brand of satire, so it’s ironic that they would be joining forces with an industry they have been targeting since the very first episode.

MacGruber appears to die at the end of every sketch, but that didn’t stop Forte and his coscreenwriters John Solomon and Jorma Taccone (who also directed) to give the ’80s action hero big-screen treatment in what is certainly one of the better sketch-to-screen SNL films in recent years. Set in the 1980s, the film shows mullet-haired MacGruber, the former Green Beret, Navy Seal, and Army Ranger, coming out of retirement to battle the villainous Dieter von Cunth (Val Kilmer), who has seized control of the X-5 nuclear missile with a nuclear warhead. MacGruber’s mission to stop von Cunth is also personal because he killed MacGruber’s wife, Casey (Maya Rudolph). When his entire team of experts is killed, MacGruber assembles a new team consisting of his old friend Vicki St. Elmo (Kristen Wiig) and Lt. Dixon Piper (Ryan Phillippe), who has difficulty adapting to MacGruber’s unorthodox methods.

In an interview with New York magazine, director Taccone described the film as “an affectionate homage to eighties-era action films like Commando and Die Hard with an idiot in the middle of it.” He added that it is “so dirty it’s hard to show things from the movie in the trailer. Ninety percent of it you can’t show.” The R-rated humor is not entirely surprising considering Taccone is one of the Lonely Island trio (with Akiva Schaffer and Andy Samberg).

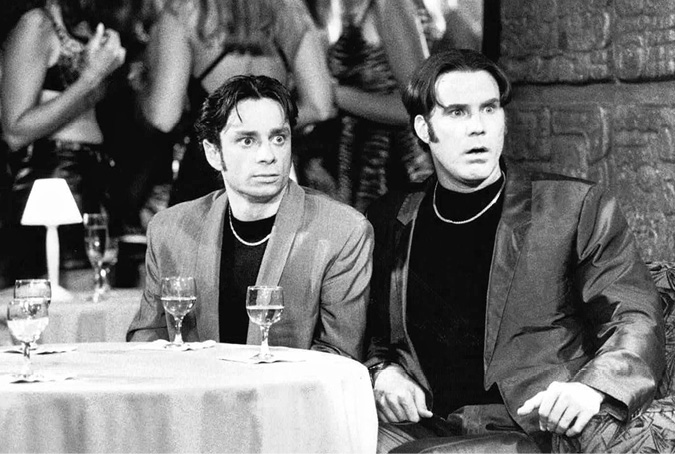

Doug Butabi (Chris Kattan, left) and his brother Steve (Will Ferrell) dream of owning their own club in A Night at the Roxbury (1998).

Some critics found the film’s comic sensibility challenging and even objectionable. In her review for the Washington Post, Ruth McCann thought MacGruber was too much of a “schmuck” and found “the whole package . . . often lamentably unsubtle. Like a kid banging pots in a kitchen, it’s a little bit funny, until it’s not.” New York Times critic A. O. Scott was puzzled by the “scatology and sexual immaturity of the humor,” which indicated that the film’s purpose was to “amuse teenagers,” yet it’s clear the filmmakers were aiming for an R rating. On a more positive note, Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers, who had not been a fan of past SNL films, commended Jorma Taccone for “spoofing the school of Stallone-Segal-Schwarzenegger with a sense of style and unabashed affection.”

A Night at the Roxbury (1998): “Score!”

Directed by John Fortenberry. Written by Steve Koren, Will Ferrell, and Chris Kattan. Producers: Amy Heckerling and Lorne Michaels. Executive Producer: Robert K. Weiss. Cinematography: Francis Kenny. Editor: Jay Kamen. Original Music: Dave Kitay.

Cast: Will Ferrell (Steve Butabi), Chris Kattan (Doug Butabi), Dan Hedaya (Kamehl Butabi), Loni Anderson (Barbara Butabi), Molly Shannon (Emily Sanderson), Dwayne Hickman (Fred Sanderson), Lochlyn Munro (Craig), Maree Cheatham (Mabel Sanderson), Colin Quinn (Dooey), Richard Grieco (Himself), Chazz Palminteri (Benny Zadir), Gigi Rice (Vivica), Elisa Donovan (Cambi), Michael Clarke Duncan (Roxbury Bouncer), Jennifer Coolidge (Hottie Cop), Meredith Scott Lynn (Credit Vixen).

Distributed by Paramount Pictures. Running time: 82 mins. Rated PG-13.

According to the press kit for A Night at the Roxbury, the film’s stars, Chris Kattan and Will Ferrell, recalled the inspiration for the Butabi Brothers. They were in a club in Los Angeles, and they observed a guy leaning against the bar who really wanted to dance. “He was sort of pathetic,” recalled Kattan. “We kept checking him out and started picking up on his expressions and mannerisms. Something about this out-of-it guy intrigued us.” Ferrell added that the guy “was dying to be a part of the scene, but he’d try and try, and come up with nothing. He was really out of his element—a dorky fish in glitzy water.”

The Roxbury Guys, Steve and Doug Butabi (Will Ferrell and Chris Kattan), made their Saturday Night Live debut on March 1996 (21.16). In the first sketch, they’re standing at the bar of the China Club moving to the beat of Captain Hollywood Project’s “More & More” and repeatedly mistakenly thinking someone is signaling them from across the room to dance. They trap an unsuspecting woman (Cheri Oteri) between them and start bouncing her between their chests. Once she gets free, they high-five each other and shout, “Score!” A few weeks later (21.20), the clueless duo are at it again with one major change—for the first time we hear what will become their official theme song, “What Is Love” by Haddaway. They are also joined by a third Roxbury guy (Jim Carrey), and together they bop their heads to the music as they try their luck at a few other venues, like a high school prom, a wedding in a catering hall, and a retirement home. Other hosts seen clubbing with the Butabi brothers include Tom Hanks (22.1), Martin Short (22.8), Alec Baldwin (22.14), and Sylvester Stallone (as Rocky Balboa) (23.1). On the flip side, host Pamela Lee (22.18) can’t seem to shake the brothers, who follow her to her gym where they pop up in the sauna and Jacuzzi.

So little was known about the duo beyond their favorite song, so veteran SNL writer Steve Koren, who penned the screenplay with Ferrell and Kattan, moved the location to Los Angeles and gave the Roxbury Guys a life outside of the clubs. Steve (Ferrell) and Doug (Kattan) Butabi are brothers and best friends who still live with their parents in Beverly Hills and work in their father’s florist shop. They dream of one day owning their own club, but they need to be able to get inside the Roxbury, which is for A-listers only. Their prayers are answered when they get into a fender bender with 1980s television actor Richard Grieco of 21 Jump Street (1987–1991) and Booker (1989–1990) fame (playing himself), who gets them into the club and brings them closer to their dream.

What follows is a short (eighty-two minute) but strained comedy. You suspect that Ferrell and Kattan had more fun making the film than the audience had watching it. With a glut of SNL films coming and going in theaters, the critics began to rank them with Wayne’s World at the top of the list as the best and several others competing for the bottom spot. Variety critic Dennis Harvey writes that as “an amiable, if flyweight diversion,” A Night at the Roxbury “stands just a peg higher” than It’s Pat, Stuart Saves His Family, and Blues Brothers 2000. New York Times critic Anita Gates observed that the film is “a lot like the brothers themselves: undeniably pathetic but strangely lovable. Still, do you really want to spend an hour and a half with them in a dark room?”

Stuart Saves His Family (1995): “You’ll laugh because it’s not your family. You’ll cry because it is.”

Directed by Harold Ramis. Written by Al Franken, based on his book. Producers: Lorne Michaels and Trevor Albert. Executive Producers: C. O. Erickson, Dinah Minot, Whitney White. Cinematography: Lauro Escorel. Editors: Craig Herring and Pembroke J. Herring. Original Music: Marc Shaiman.

Cast: Al Franken (Stuart Smalley), Laura San Giacomo (Julia), Vincent D’Onofrio (Donnie), Shirley Knight (Stuart’s Mom), Harris Yulin (Stuart’s Dad), Lesley Boone (Jodie), John Link Graney (Kyle), Julia Sweeney (Mea C.), Joe Flaherty (Cousin Ray), Robin Duke (Cousin Denise).

Distributed by Paramount Pictures. Running time: 95 mins. Rated PG-13.

Stuart Smalley (Al Franken) is a “caring nurturer” (but not a licensed therapist) who hosts his own cable access show in Chicago, Daily Affirmation with Stuart Smalley. He is also a member of several 12-step programs, including Adult Children of Alcoholics, Overeaters Anonymous, Debtors Anonymous, and Al-Anon, a support group for friends and relatives of alcoholics. Julie (Laura San Giacomo) is his best friend, confidante, and Al-Anon sponsor who is there for him when his life is on a downward spiral. His show gets canceled, and then he gets sucked into Smalley family drama triggered by an inheritance left by Stuart’s recently departed Aunt Paula. Stuart’s family is a bastion of dysfunction. His dad (Harris Yulin) is a mentally and emotionally abusive alcoholic, while his mother (Shirley Knight) is his enabler. His sister Jodie (Lesley Boone) is addicted to food and abusive men, and his unemployed brother Donnie (Vincent D’Onofrio) drinks and smokes pot. Stuart does his best to keep his distance, but his efforts to help settle a family legal matter lands the Smalley family in court. While Stuart has newfound success when his Daily Affirmation show is picked up by a cable network, his family back in Minnesota continues to fall apart. When his drunken father accidentally shoots Donnie, the Smalley family plans an intervention in hopes that Dad will agree to go to rehab.

Stuart Smalley’s first Daily Affirmation episode aired on SNL in February 1991 (16.12). Over the next four seasons, Stuart dispensed words of wisdom to SNL viewers, usually in the form of 12-step platitudes (“Denial ain’t just a river in Egypt,” “It’s just stinking thinking,” etc.). He has also welcomed some very special guests on his show, like basketball great Michael J. (no last name to protect his anonymity), who encourages him to repeat the affirmation, “I don’t have to be a great basketball player.” Stuart helps another basketball great, Charles B. (19.1), with some help from Muggsy B., to own the fact that despite all his success, he still feels empty inside because it’s not coming from (pointing to his heart) here. Franken’s character could easily be misperceived as a parody of 12-step, New Age, self-help types, which it is not. If you read Franken’s book of daily affirmations, I’m Good Enough, I’m Smart Enough, and Doggone It, People Like Me, it’s actually firmly rooted in the philosophy of 12-step programs.

“And doggone it, people like me!” is the mantra of television host Stuart Smalley (Al Franken) in Stuart Saves His Family (1995).

Stuart Smalley was inspired by Al Franken’s experiences in Al-Anon, a 12-step program for family members and friends of alcoholics. In a 1995 interview with Nancy Spiller, Entertainment News Services, Harvard-educated Franken explained that one of the things he learned in Al-Anon is that “you can learn from people who aren’t necessarily smarter than you. I’d hear somebody say something and I’d be very judgmental and say, ‘Oh, that person’s an idiot,’ and a month later the same person would say something that would touch me deeply.” Although he won’t discuss his own family, he does reveal that his father was not an alcoholic, and the dysfunctional Smalleys were not modeled after his own family.

What distinguishes Stuart Saves His Family from the other SNL sketch film is that it is genuinely trying to say something about family, human relationships, and self-esteem. Roger Ebert found the film to be “a genuine surprise. A movie as funny as the SNL stuff, and yet with convincing characters, a compelling story and a sunny, sweet sincerity shining down on the humor.” But other critics were not convinced. Peter Rainer, critic for the Los Angeles Times, found Franken’s “deep-down commitment to Stuart’s dumpy self-love” on SNL to be “funny” and “touching” but accused Franken of “starting to take Stuart altogether too seriously. It’s kind of creepy.” New York Times critic Janet Maslin was even more dismissive, calling Stuart Saves His Family “little more than a set of intermittently funny skits strung together by a sketchy nonplot about Stuart’s relatives.”

Hopefully, no one showed the reviews to Stuart, who would probably end up curled up in bed with a box of Oreos and the covers over his head.

Superstar (1999): “Dare to dream.”

Directed by Bruce McCulloch. Written by Steve Koren. Based on characters created by Molly Shannon. Producer: Lorne Michaels. Executive Producers: Robert K. Weiss and Susan Cavan. Cinematography: Walt Lloyd. Editor: Malcolm Campbell. Original Music: Michael Gore.

Cast: Molly Shannon (Mary Katherine Gallagher), Will Ferrell (Sky Corrigan/Jesus), Elaine Hendrix (Evian), Mark McKinney (Father Ritley), Harland Williams (Slater), Glynis Johns (Grandma).

Distributed by Paramount Pictures. Running time: 81 mins. Rated PG-13.

According to the film’s production notes, Shannon created Mary Katherine Gallagher when she was a student at New York University during an improvisation exercise in which actors were required to enter and introduce themselves as a character. Mary is a “combination of herself, her childhood friend Ann Ranft, and ‘no one in particular.’” The character was refined in a show she cowrote after college with Rob Muir and later through her collaboration with SNL writer Steve Wayne Koren, who wrote the screenplay for Superstar. Shannon explains her appeal: “I think people identify with her adolescent struggles because she’s hopeful. It’s not like she’s just a loser that’s not going to succeed, but she has hope and she’s a fighter. She gets hurt and put down but she never lets that defeat her. She just keeps going after what she wants. She’s a character with a lot of heart and passion.”

Like her creator, there is something genuinely appealing about the awkward and geeky Gallagher. Although the film is short on plot, the gag-driven story centers around Gallagher’s two goals in life: win a school talent contest and get a first kiss, preferably from the school’s star football player, Sky Corrigan (Will Ferrell), who unfortunately is hot and heavy with her blonde (and bulimic) nemesis, Evian (Elaine Hendrix). We learn more about Mary Katherine’s background and meet her wheelchair-bound guardian/grandmother (Glynis Johns), a former Broadway hoofer, who is against her granddaughter pursuing a career in show business. As one would expect, the humor is a bit sophomoric and the jokes are very hit-and-miss, but under the direction of Bruce McCulloch, the film is fueled by the performers’ high energy level, especially Shannon and Ferrell, and some enjoyable musical moments, like a robot-dance number in the cafeteria. Variety’s Dennis Harvey was pleasantly surprised by “this amusing, if uneven, comedy,” but other critics were not, like the New York Times’ Anita Gates, who remarked that Shannon is “in fine form as the heroine” but couldn’t get past the fact that “the majority of the jokes fall flat, and in the end Mary Katherine has proved (and she would have trouble accepting this) that she’s a joy only for five minutes or so at a time.”

Nuns keep their eye on Mary Katherine Gallagher (Molly Shannon, center), a Catholic school girl with a big dream in Superstar (1999).

Wayne’s World (1992): “You’ll laugh. You’ll cry. You’ll hurl.”

Directed by Penelope Spheeris. Written by Mike Myers, Bonnie Turner, and Terry Turner. Based on characters created by Mike Myers. Producer: Lorne Michaels. Executive Producer: Howard W. Koch Jr. Cinematography: Theo van de Sande. Editor: Malcolm Campbell. Original Music: J. Peter Robinson.

Cast: Mike Myers (Wayne Campbell), Dana Carvey (Garth Algar), Rob Lowe (Benjamin Kane), Tia Carrere (Cassandra), Lara Flynn Boyle (Stacy), Michael DeLuise (Alan), Dan Bell (Neil), Lee Tergesen (Terry), Kurt Fuller (Russell Finley), Chris Farley (Security Guard), Meat Loaf (Tiny), Colleen Camp (Mrs. Vanderhoff), Ione Skye (Elyse).

Distributed by Paramount Pictures. Running time: 94 mins. Rated PG-13.

Wayne’s World 2 (1993): “You’ll Laugh Again! You’ll Cry Again! You’ll Hurl Again!”

Directed by Stephen Surjik. Written by Mike Myers, Bonnie Turner, and Terry Turner. Based on characters created by Mike Myers. Producer: Lorne Michaels. Coproducers: Dinah Minot and Barnaby Thompson. Executive Producer: Howard W. Koch Jr. Cinematographer: Francis Kenny. Editor: Malcolm Campbell. Music: Carter Burwell.

Cast: Mike Myers (Wayne Campbell), Dana Carvey (Garth Algar), Christopher Walken (Bobby Cahn), Tia Carrere (Cassandra Wong), Kim Basinger (Honey Hornée), Kevin Pollack (Jerry Segel), Chris Farley (Milton), Lee Tergesen (Terry), Dan Bell (Neil), Rip Taylor (Himself), Aerosmith (Steven Tyler, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Hamilton, Joey Kramer), Ralph Brown (Del Preston), James Hong (Jeff Wong).

Distributed by Paramount Pictures. Running time: 95 mins. Rated PG-13.

In a Wayne’s World reunion celebrating the film’s twenty-first anniversary, Mike Myers explained that Wayne’s World grew out of his years as a “heavy metal kid in the suburbs of Toronto” and his fascination with Manhattan Cable, which aired cable access programs like The Robin Byrd Show. Wayne’s first appearance was on a segment entitled “Wayne’s Power Minute,” which aired on It’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll, a 1987 summer series on CBC Television. In his first segment, he points out the misspellings in the names of heavy metal bands (there should be an “e” in “Led Zepplin” and “Ratt” shouldn’t have two “t’s”).

Wayne’s World debuted on February 19, 1989 (14.13), as a graveyard sketch (the last sketch of the night, between the last musical performance and the “good nights”), which usually means one of two things: comedy wise it’s not up to par with the rest of the show, or it’s so far out there that only the die-hard SNL fans will still be tuned in. The latter may have been true, but the former was certainly—to quote Wayne and Garth—“not!” Wayne’s World is a cable access television show broadcast from Garth’s house over Cable 10, a community access channel in Aurora, Illinois. Their guests that night were Garth’s father, Beev (Phil Hartman), who owns the Wishing Well convenience store, and an excellent babe from school, Nancy (Jan Hooks). In a 1990 interview for The Floridian, Myers told Eric Snider that Wayne’s World is a spoof of “the adolescent suburban heavy metal experience” and Wayne was much like the guys he grew up with in the suburbs of Toronto. Although Wayne Campbell is Myers’s creation, he also gives credit to his four collaborators on the SNL writing staff—Greg Daniels, Conan O’Brien, Robert Smigel, and Bob Odenkirk. Much of the sketch’s humor is rooted in the language, namely the exchanges between Wayne and Garth, whose catchphrases consist of teen jargon. Wayne’s World has the distinction of contributing to the teen lexicon of the late 1980s/early 1990s—words and phrases like “Babelicious,” ”Schwing!,” and “We’re not worthy!” (see chapter 21 for a complete list).

Wayne’s World and its sequel, Wayne’s World 2, are the SNL films that got it right. The central characters—Wayne and Garth—are not only from the same demographic that the film is targeting (teenagers, particularly males), but they share the same cheeky, postmodern comic sensibility. Its style is reminiscent of a Marx Brothers movie in which the plot merely functions as a device to hold a string of gags together, most of which involve references to pop culture. Wayne’s World even has a “Scooby Doo” ending, while one of the endings of Wayne’s World 2 has Wayne and Garth driving over a cliff à la Thelma & Louise (1991). The sequel also references kung-fu movies, The Graduate (1967), and The Doors (1991). The humor is also highly self-reflexive. Two decades before 30 Rock, Wayne’s World featured a hysterical sequence that points out the use of product placement within the film.

The plots (a term I use loosely here) of both films revolve around Wayne’s battle against the establishment in the form of a network that takes over his cable show and a handsome TV executive (Rob Lowe) who causes problems for a jealous Wayne and his girlfriend Cassandra (Tia Carrere), a rock singer from Hong Kong. It’s an ironic premise considering the filmmakers can also be accused of taking a television sketch and turning it into a feature-length film to make some cash (but hey, that’s Hollywood). In Wayne’s World 2, Wayne is jealous of a sleazy music executive (Christopher Walken), who is trying to break up him and Cassandra so he can make her a star. With the help of the spirit of Jim Morrison, Wayne is on a mission to do something with his life, so he organizes Waynestock, a music festival. If only he could get Aerosmith to play.

Wayne’s World took many critics by surprise. Roger Ebert admitted he walked in expecting a “dumb, vulgar comedy,” but was surprised by the film’s “genuinely amusing, sometimes even intelligent undercurrent.” New York Times critic Janet Maslin observed that the reason the film succeeds is that Wayne and Garth’s “mock-moronic attitudes are intentional and the viewer is let in on the joke.” Not everyone appreciated the film. Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times felt it was “unimaginatively padded” as “there is not nearly enough satisfactory plot and incident to film’s bare bones 95 minutes.”

It sounds like the movie made him hurl.

Wayne’s World posed a challenge for its distributor, Paramount Pictures, as every other word of dialogue is an expression to which there needs to be an equivalent in non-English-speaking countries. The solution was to create and distribute pocket-sized dictionaries in German, French, Italian, and Spanish that contained translations of some of the more popular phrases.