Running from the well-heeled suburbs of the west to the mock-Tudor heartlands of Essex is the Central line. It takes in west London, the West End, the City, the East End and the new Olympic sites at Stratford. In 1900, it opened as the egalitarian ‘twopenny Tube’, running from Shepherd’s Bush to Bank. Mark Twain was a passenger on its inaugural journey. To the west of Holborn is a disused station called British Museum. During World War II, the tunnels between Leytonstone and Gants Hill were used as a secret factory for aircraft components.

Bank and St Paul’s bring you to two of the most important sites in the City of London, which for so many centuries was the entirety of London. When we visit European cities, we tend to stick to sightseeing in the historic centre, yet Londoners are often cut off from the inheritance of their own centro storico. The City is a living museum of treasures, but the only people going there habitually are the ones moving around imaginary money in computers and those who make their sandwiches. When Wren’s churches were under threat, T.S. Eliot wrote that they gave ‘to the business quarter of London a beauty which its hideous banks and commercial houses have not quite defaced . . . the least precious redeems some vulgar street’.

HOLLAND PARK

REMAINS OF HOLLAND HOUSE

Holland Park, W8 6LU

The Grand Tour of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was a sort of gap year for aristocrats. Once in Italy, they would feast on the remnants of the Roman world, and often develop a taste for ruins. Fragments of ancient castles, temples and arches were decreed ‘picturesque’, and perhaps gave the emergent British Empire a titillating preview of its own annihilation. Our own picturesque ruin can be found at the centre of Holland Park, courtesy of the Luftwaffe. Built in 1605, Holland House (originally Cope House) was a substantial stately home, used by royals and Roundheads alike. In the early nineteenth century, the 3rd Lord Holland established a salon that became the unofficial Whig headquarters; it was from here that the Great Reform Act of 1832 was plotted. A distinguished CV was curtailed in 1940, when the house was struck by twenty-two German bombs in a single night. Today, it looks as though three-quarters of Holland House is missing, which is indeed the case. The east wing remains intact, along with a little of the ground floor. A three-sided, recessed portico walkway, with round arches and fleurs-de-lis garlanding its roof, traces where the façade once stood. Currently a youth hostel, the east wing features gables and an attractive bay window, and at its rear stands a solitary turret from the main house. Amputated from the great house it once served, the walkway could now be a theatre prop; the mutilated fragments seem as forlorn as severed limbs scattered across a battlefield.

KYOTO GARDEN

100 Holland Park Avenue, W11 4UA

The historic city of Kyoto was the Japanese capital for over a millennium. Today it is home to some 400 Shinto shrines and 1,600 Buddhist temples, including the Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Londoners wishing to indulge in quiet contemplation need not endure the twelve-hour flight to Japan, for at the secluded heart of Holland Park sits the Kyoto Garden. To mark 1992’s Japan Festival in London, a prominent Japanese designer landscaped this garden in accordance with Zen principles. Koi carp dart around the pool’s stone lanterns, and peacocks strut across the lawns. In autumn the diminutive maple trees display leaves of red and gold. Centre-stage is a waterfall, cascading into the pond over tiers of carefully placed rocks, with a staggered wooden bridge across the pond offering the best views. It all makes an atmospheric replica. A new section was added in 2012 in thanks for the United Kingdom’s support after the nuclear accident at Fukushima.

TILES

Debenham House, 8 Addison Rd, Kensington, W14 8DJ

An ageing prostitute is haunted by the death of her daughter. Across town, a lunatic waif who is the daughter’s double lives alone in a ten-bedroom house after the death of her own mother (who in turn looked just like the prostitute) and one day the pair meet on the top deck of a No. 27 bus . . . If Joseph Losey’s 1968 film Secret Ceremony sounds a cul-de-sac of nonsense, that’s because it is, but something about this nasty, psychotic film stays with the viewer. That something is probably the film’s inspiration and true star, the extraordinary house at 8 Addison Rd. Sometimes called Peacock House, it was built in 1907 for the owner of the famed department store (Debenhams, not Peacocks). The startling exterior is clad in tiles of lustrous blue above green, framed by rows of cream terracotta. Art nouveau looked to nature, and these colours were chosen accordingly; the tiles match the sky and gardens, making the house seem a transparent spectre. With sensible stucco-fronted houses for neighbours, Debenham House stands out as a cabaret drag act. The exotic interior boasts an inner dome of Byzantine mosaics: gold, Greek lettering and zodiac animals straight from Ravenna. The house is not open to the public, but one can take in its exterior from the street and peek through the gate down an arcaded walkway.

QUEENSWAY

THE ELFIN OAK

Kensington Gardens, W2 2UH

This whimsical creation is not to everyone’s taste, but it should light up the faces of the young and the young-at-heart alike. The Elfin Oak is a 900-year-old tree. In 1928 it was moved from Richmond Park to Kensington Gardens, and in 1930 the artist Ivor Innes picked up his carving knife to create a community of little people living on and within the tree. Some characters help each other to climb up the tree, some sit astride protruding knobs of wood, and some shelter in hollows. The fantasy includes elves, gnomes, princesses, witches, animals, people dining around a giant flat toadstool, and even a well-stocked elf library where a literary pixie sits with a pot of quill pens. The detail, from varied facial expressions to neckerchiefs, belt buckles and musical instruments, is accomplished. The artwork of Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma album shows David Gilmour posing before the tree. The Elfin Oak was showing signs of deterioration when Spike Milligan intervened, leading to its restoration in 1996 and Grade II listing. Sited beside the café at the entrance to the Princess Diana Memorial Playground, it is now protected by a cage. Complementing the oak is the Peter Pan statue located south of the Italian Gardens.

23–24 LEINSTER GARDENS

W2 3AN

Appearances can be deceiving. In the salubrious streets to the north of Hyde Park is a row of terraces, chiefly housing hotels. Take a closer look and you will realize that two houses are hollow façades covering a blank space. The original houses at this address were demolished to make way for Underground train tracks and replaced with a phantom façade that mimics the Henry VIII Hotel next door. The first-floor windows are framed by Corinthian columns, pediments and balconies, some of which even have potted bay trees to match those of the hotel. Decoration gradually lessens until the servants’ quarters on the top floor. There are a couple of hints that all is not what it seems, such as pristine grey paint in lieu of glass panes, and the joints in the front doors being painted over, but the effect is uncanny and slightly eerie. If this all seems hard to fathom, walk to Porchester Terrace where, like Dorothy confronting the Wizard, you will see nothing except a few iron beams propping up the impostor.

MARBLE ARCH

10 HYDE PARK PLACE

Tyburn Convent, W2 2LJ

In Porto, the one-metre gap between the baroque twin churches of Carmo and Carmelitas contains a little house, built to prevent illicit liaisons between the nuns and monks. It is tempting to envisage a similar story for 10 Hyde Park Place, itself attached to a convent and London’s smallest house at just 106 cm wide. The façade curves towards the convent and matches its red brick, making it look like a mere appendage, so it’s a surprise that No. 10 should have its own number. It was originally a house in its own right, built in 1805 to prevent access to St George’s graveyard. At the time, medical schools would pay a handsome fee for fresh corpses and many took to the grisly career of bodysnatching. The convent owns the property now, and the physical similarities to the parent building date from restoration after the Blitz. Halfway down the chapel wall, a door opens onto a tiny balcony that would make an excellent outdoor pulpit should the nuns wish to harangue the frisbee players of Hyde Park.

CHANCERY LANE

OSTLER’S HUT

The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, WC2A 3TL

The four Inns of Court around Fleet St and Chancery Lane are London’s equivalent of Oxbridge colleges. In the midst of the city’s mayhem, they are hermetically sealed worlds with splendid old buildings, chapels, cloisters and gardens. These tranquil surroundings are where London’s barristers ply their trade. The gardens at Lincoln’s Inn were the venue for the first performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and across the lawn from the great library is the smallest listed building in London. Barely larger than a phone box, this diminutive structure is nevertheless quite fancy. Each side displays a carved coat of arms within a ziggurat gable, the door has a Gothic arch, and tiny octagonal railings crown the roof. It was built in 1860 to shelter the ostler, a sort of valet who looked after the horses of those attending Lincoln’s Inn. By the end of the century the motorcar had arrived, and the job did not survive long; perhaps the hut is now used by the gardeners or to lock up disruptive young lawyers. Entrance to the Inns is via the sixteenth-century gatehouse facing Lincoln’s Inn Fields. In this large square you can also find the house of the architect Sir John Soane, now a free museum crammed with his collections from antiquity. To find the ostler’s hut, walk straight ahead past the Great Hall then turn left.

CHERRY TREE

Ye Olde Mitre, 1 Ely Place, EC1N 6SJ

Should you ever find yourself pursued by the Metropolitan Police, you can always buy a few hours by slipping through the iron gates of Ely Place, off Holborn Circus, and claiming sanctuary. This cul-de-sac does not, technically, belong to London but to Cambridgeshire, and the police are forbidden to enter without prior invitation by the Commissioners of Ely Place. The Bishops of Ely kept their townhouse here; wishing to conduct business in London without leaving their diocese, they made the area an exclave. While you wait for the Cambridgeshire Constabulary to make the long drive down the A10, there is plenty to divert you. Ely Place boasts its own chapel (St Etheldreda’s, an atmospheric thirteenth-century church) and a pub. Ye Olde Mitre is an intimate, wood-panelled bar with three snug rooms and an outer yard, whose current incarnation dates back to 1772. Behind a glass partition in the pub doorway, the remains of a cherry tree mark the boundary between the bishops’ property and that of Elizabeth I’s favourite, Christopher Hatton. Legend has it that she and Hatton danced the maypole around this tree. Ye Olde Mitre is accessed via a blink-and-you-miss-it passageway on Hatton Garden, a convenient location for jewel thieves.

ST PAUL’S

THOMAS BECKET

St Paul’s Churchyard, EC4M 8AD

The four knights caught up with the Archbishop of Canterbury on his way to vespers, climbing the stairs to the cathedral choir. An eyewitness wrote that when the fourth blow was struck, ‘the blood white with the brain, and the brain red with the blood, dyed the floor of the cathedral’. It was 29 December 1170, one month after Thomas Becket had excommunicated Henry II for crowning his son as heir apparent in the archbishop’s absence. The ascetic clergyman had spent his tenure clashing with his former friend, and had only recently returned to England after six years in exile. Becket was canonized after his murder, and the shrine holding his remains attracted many visitors to Canterbury until Henry VIII had it destroyed. In the gardens south of St Paul’s Cathedral you can find a modern interpretation of Becket’s stricken final moments in the form of a 1970 sculpture by Edward Bainbridge Copnall. Resin imitating bronze, the statue is rather expressionist. Becket lies prostrate as if pushed over, his head tilted back with hands aloft for protection or mercy. Becket being a native of Cheapside, the City of London purchased the sculpture and brought him back home.

SHEPHERD AND SHEEP

Paternoster Square, EC4M 7DX

Step through Temple Bar to find yourself in a very twenty-first-century space: the semi-public piazza. The Luftwaffe levelled the lively Paternoster area north of St Paul’s and the medieval street plan was replaced by a dreary cluster of cafés and office blocks. New plans were shunted back and forth until 2003, when the area was rebuilt and the Stock Exchange moved in. Its stone and brick materials are a nod to Christopher Wren, but the rather blank buildings are closer to the rationalist style of Mussolini’s EUR district in Rome. Despite its tasteful design, the square strikes an inauthentic note. In the wake of the financial crisis, the High Court prevented the Occupy protesters from entering Paternoster Square, decreeing that this ‘public space’ was private property with no right of way. Two focal points attempt to humanize the space: a gold-crowned column in the style of Wren’s Monument stands at less than half the height of the original, as if genuflecting before St Paul’s, while a sculpture by Elisabeth Frink is one of the few features to have survived the redevelopment. One of Britain’s major post-war artists, Frink was known for her angular, menacing birds, but this is a benign work in which a shepherd clutches his staff and drives five sheep into the square. Apart from the obvious religious connotations, Shepherd and Sheep is a nod towards Paternoster’s history as a livestock market. The Occupy movement might well look upon it and counsel us to ‘Wake up, sheeple.’

PANYER BOY

Panyer Alley, EC2V 6AA

Beside the main entrance to St Paul’s station is a row of new cafés and restaurants that make up the edge of the Paternoster Square development. Attached discreetly to the wall is something much older. Within a simple frame is a small engraving of a boy, his face entirely eroded, climbing into what looks like a basket. The panyer boy has been around for so long that nobody knows where he came from or what exactly he is up to. From the late sixteenth century we have written references to an image of a baker’s boy sitting on his bread basket, which could be the panyer boy. Some commentators see a woolsack or a coil of rope, Bacchus pressing grapes or the Greco-Roman trope of a boy pulling a thorn from his foot. Evidence points to the boy being older than the accompanying slab of text beneath him: ‘When yv have sovght the citty rovnd yet still ths is the highst grovnd avgvst the 27 1688.’ We can be grateful that no one has taken the text literally and decided to rehouse the panyer boy at the top of the Shard.

GOLDEN BOY OF PYE CORNER

1 Giltspur Street, EC1A 9DD

He stands stark naked but coated in gold, with corkscrew curls and a sneer on his fat little face. Perching high above us with folded arms, his disdainful gaze is fixed higher still on the heavens, like Nero crossed with the Manneken Pis from Brussels. This indolent homunculus marks the spot where the Great Fire of London was finally stopped. The fire having started at Pudding Lane, contemporary preachers detected a message from an evidently literal-minded God that London had been punished for ‘the sin of Gluttony’. The golden boy was initially assigned to the Fortune of War pub, later infamous as a haunt of bodysnatchers, and remained in situ when the pub was demolished in 1910. An inscription on the new building explains that ‘the boy was made prodigiously fat to enforce the moral’, but in these high-fructose times he could pass for any average inner-city child queueing up for chicken and chips. Pye Corner is at the meeting of Giltspur St and Cock Lane; the latter earned its name as a venue for cockfighting or prostitution, depending on whose story you believe.

MEMORIAL TO HEROIC SELF-SACRIFICE

Postman’s Park, EC1A 4EU

Stories of self-sacrifice have an enduring popularity; it’s comforting to think that should we find ourselves in peril, other people would be altruistic enough to risk everything for our safety. This tranquil spot, a park created in 1880 on the site of three former churchyards, takes its name from the then-adjacent General Post Office. Visitors do not contemplate Nelson or Wellington, but displays of bravery from ordinary citizens at the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice. An idea of the painter George Frederic Watts, it is a wall of ceramic tiles, each dedicated to someone who died trying to save others in episodes of fire, drowning or stampeding animals. The youngest was nine years old. Some quote the last words of the dying, some describe bizarre scenarios; one man ‘saved a lunatic woman from suicide at Woolwich Arsenal but was himself run over by the train’. The display walks a tightrope between heart-rending and kitsch, but what amplifies its poignancy is that the memorial was never finished. Four of the 120 spaces were filled by tiles upon its opening in 1900. After Watts’s death people gradually lost interest in the project. To this day only fifty-four spaces have been taken. After a seventy-eight-year interval, a new tile was added in 2009.

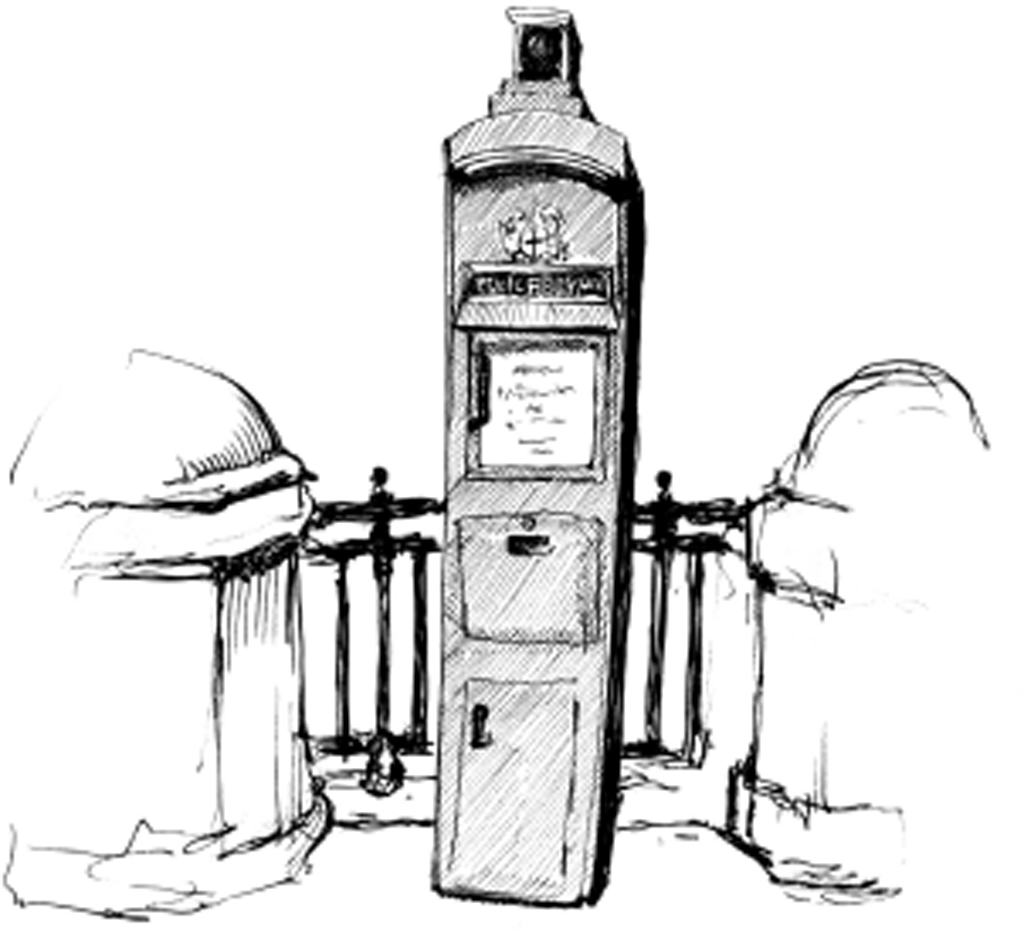

POLICE TELEPHONE POST

1 St Martin’s le-Grand, EC1A 4EU

This post, directly beside the entrance to Postman’s Park, is just one of a few police posts in central London. Painted a smart and vivid cyan blue, they are topped by a round, coloured lightbulb within a square frame. A sign will usually explain that they are no longer operational. In the period after telephones but before walkie-talkies, these phone posts allowed officers to spend more time on patrol, and the public to contact the nearest station in the event of emergencies. Most of the posts simply contained a phone and a first-aid box, but there were also larger boxes with lighting, heating and a desk inside. It was these boxes that in 1963 were immortalized by the Tardis of Doctor Who. By the late sixties the posts and boxes had become obsolete and most were demolished, but a few remain in place. Others can be found at Guildhall Yard, Walbrook, Old Broad St and Victoria Embankment. As the classic London phone-box design was inspired by the tomb of Sir John Soane, so the lightbulb over police posts is said to take after his lantern design for Dulwich Picture Gallery.

BANK

ALTAR

St Stephen Walbrook, 39 Walbrook, EC4N 8BN

The City churches will forever be associated with their mastermind, Christopher Wren; St Paul’s is the iconic masterpiece, with a dome as famous as those of Florence or Rome, but a personal favourite is the dazzling bright white of St Stephen Walbrook. Wren’s design is celestial but what makes the church unique is its 1987 rearrangement, when a new altar by sculptor Henry Moore was placed at the centre. Here, modernism is welcomed inside by the Renaissance; the result is not a clash but a perfect synthesis. The altar is made of Travertine marble from the same quarry used by Michelangelo. In this context, the solid block with Moore’s characteristic bumps and contours looks timeless and could perhaps pass for an altar from an early Christian catacomb. Protests over its validity as an altar saw the Court of Ecclesiastical Causes Reserved, the highest court in the Anglican Church, meet for only the second time in its history; the altar was given the stamp of approval.

THE CORNHILL DEVILS

54–55 Cornhill, EC3V 3PD

The devil is in the detail, literally so in the case of 54–55 Cornhill. Clad in placid pink terracotta, this late Victorian building sits next door to the Wren church of St Peter’s, and at first glance appears an unlikely repository for an immortalized vendetta. The architect was dragged into a territorial dispute with the rector over one foot of contested land, and compelled to redraw his plans. His revenge took the form of three demonic beasts, erected in 1893, who crouch on tiny perches on the façade, staring down at the doorway of St Peter’s. With horns on their heads and stegosaurus plates on their backs, the contorted bodies lean forward to spit and hiss curses at churchgoers. One demon is much smaller than the other two, and another is made more monstrous by a plump pair of breasts, provoking blasphemous inklings that they could be an infernal inversion of the Holy Family; the third is thought to be a likeness of the obstinate clergyman in question.

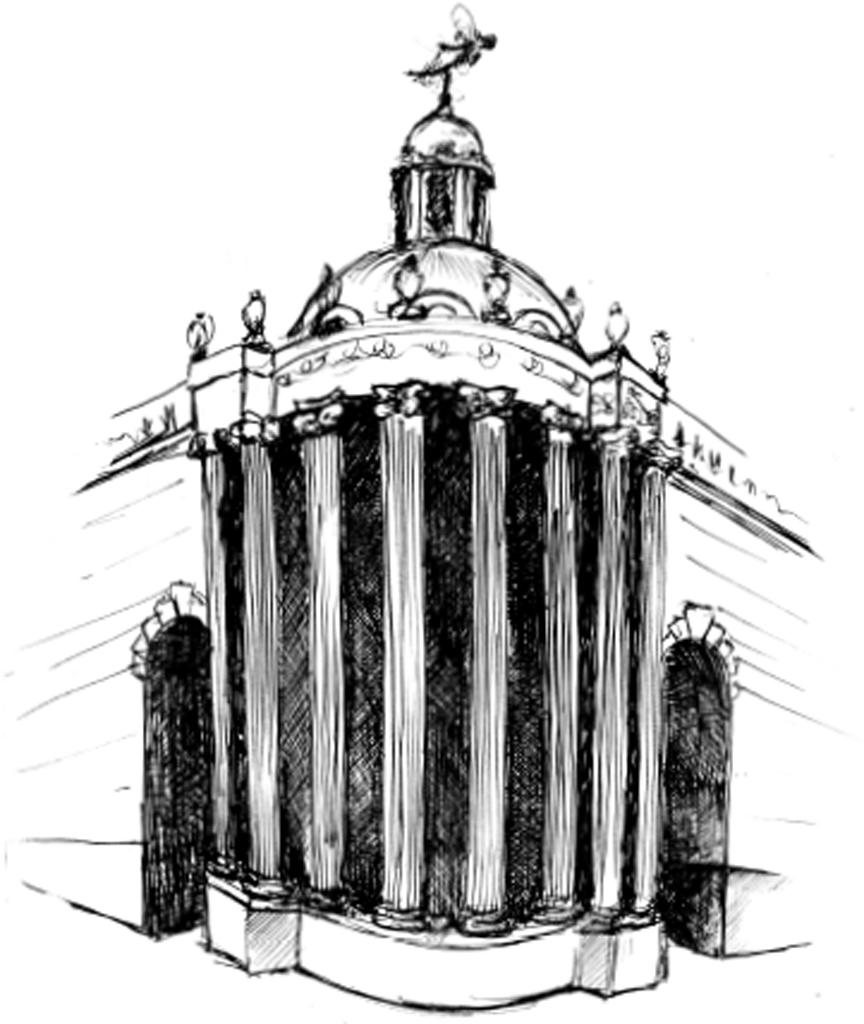

The Bank of England, Threadneedle Street, EC2R 8AH

Little of Sir John Soane’s famed Bank of England building is left to us except its outer walls; Herbert Baker’s expansion of the bank in the twenties and thirties entailed the controversial demolition of most of Soane’s work. One partial survivor, at the rear on the corner of Princes St and Lothbury, is Tivoli Corner. Soane was much enamoured of antiquity and a favourite building was the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli, which perches dramatically on a precipice above a deep valley. It inspired this ring of Corinthian columns that add a flourish to the Bank’s walls. Baker replaced the crowning attic with a copper dome, topped by a cupola and a golden statue of Ariel. He also opened up the corner with a pair of archways, creating a tunnel to offer pedestrians shelter or a quick shortcut. To pass through is to momentarily find yourself within a Roman mausoleum. Stand out on the street, and the Pantheon-style open oculus in the roof looks onto that golden statue; both intensify the blue of the sky, and provide a wonderful frame for the clouds racing by. In the eyes of Soane’s admirers, Baker added insult to injury by recycling two capitals from Tivoli Corner as bird baths at his country house in Cobham. A few paces down Lothbury, a niche houses a statue of Soane, clutching draughtsman’s tools and sporting a formidable frown, as well he might. Some suggest that this allusion to a Roman ruin was intended as a gentle reminder to the forces of Capital that all empires eventually fall; we’re still waiting.

GRASSHOPPER

Royal Exchange Buildings, EC3V 3NL

Set slightly back from the junction at Bank station, at the rear of the piazza-cum-traffic island, is the dramatic sight of the Royal Exchange. It opened on this site in 1570, but burned down twice and what we see today is Victorian. Its monolithic façade echoes Rome’s Pantheon, columns propping up a pediment in which Commerce stands on a plinth, presiding over the transactions of exotic-looking traders from the far-flung corners of the globe. Few notice the large golden insect above the rear steeple, acting as a weathervane. Does it allude to the cautionary fable of the grasshopper and the ant? The mundane truth is that it comes from a family coat of arms. Sir Thomas Gresham was a financial wizard whose ability to play the markets made him indispensable to successive British monarchs. He founded the Exchange as a venue for traders, in imitation of the Bourse at Antwerp. To maximize his profits, Gresham shrewdly added two upper tiers that were rented out to shopkeepers, creating the first shopping mall. It seems fitting that today’s Exchange building should be largely given over to luxury boutiques. A few doors along, you can see another Gresham grasshopper, above the entrance to 68 Lombard St.

THE ROYAL PROCESSIONS

1 Poultry, EC2R 8EJ

Within the huddle of prominent buildings around Bank station, the joker in the pack is No. 1 Poultry. It strides into a meeting of sober neo-classical porticoes like a circus clown at a funeral. Often referred to as a keystone of postmodern architecture, after a protracted gestation this controversial building was completed in 1997. The bands of pink and yellow limestone across each wavy segment give it a contemporary look; it’s a very hungry caterpillar taking a huge bite out of the City. Time Out readers voted it among the five worst buildings in London, but it is only recently that the ‘concrete monstrosities’ of the 1960s have been reappraised, so later generations may find value in the building’s bold insouciance. The ‘Royal Processions’ frieze of its predecessor from 1875 was saved, and is now incorporated into Poultry’s north side. Depicted in terracotta are four monarchs (Edward IV, Elizabeth I, Charles II and Victoria) believed to have passed this spot while entering London. The work is full of detail, personality and humour; to compare the period costumes is like taking in all four series of Blackadder at a glance. Courtiers, soldiers and horsemen bark instructions and gesticulate to one another as they clear the way. Charles has two spaniels at his feet. The two queens are carried in a litter and a carriage respectively, and, for once, Queen Victoria looks amused.

CEILING

St Mary Aldermary, Watling Street, EC4M 9BW

A Gothic Wren, this church is something of a rarity: the widow paying for its rebuilding stipulated that Christopher should provide an imitation of the burnt original. St Mary Aldermary’s distinctive tower is prominent in the streetscape east of St Paul’s, its top parapet bolstered by four slim turrets tapering off into gold caps. The best feature, though, is found inside; a beautiful fan-vaulted ceiling in crisp, icing-sugar white. The fan shapes resemble rows of displaying peacocks, and the gaps in between are filled with shallow domes. The central aisle of the nave, higher than the others, has six white domes with a seventh above the altar that is all red, black and gold heraldry. Admittedly, not everyone will get excited by a church roof, but this ceiling is an all-singing, all-dancing cabaret revue among dour kitchen-sink dramas. Within office hours, the church doubles as a café. In the pews, the congregation slurps on soup and coffee, and the place gets much more use than it would as a place of worship.

TURKISH BATHS

8 Bishopsgate Churchyard, EC2M 1RX

Enter Bishopsgate Churchyard, one of the more pleasing green spaces in the City, and carry on past St Botolph’s Church and the abstract sculptures installed between benches. You will find a narrow courtyard before Old Broad St, and at its centre a small kiosk fitted out like the garden shed of an Ottoman sultan. Tiling in bands of cream and red at the base gives way to diverse shades of blue. Its three-sided front has small star windows and longer ones with ogee arches. The windows are bordered by elaborate decorative patterns in terracotta. On the roof is an onion dome in coloured glass, from which protrudes a star and a crescent, and there is more fancy tiling downstairs. This singular little place originally served as an entrance to subterranean Turkish baths; one of five run by the Nevill brothers, this branch was given its arabesque makeover in 1895. The baths closed in the years of post-war austerity but the building periodically springs to life as a cocktail bar or a pizzeria. On my last visit, though, the only sign of life was a letter in the window advising that the leaseholder could collect his belongings from the bailiff.

BEDOUIN TENT

St Ethelburga Centre, 78 Bishopsgate, EC2N 4AG

This tiny church is the calm at the centre of the Bishopsgate storm. With the Gherkin looming over it, St Ethelburga seems the size of a postage stamp, clinging to its spot between the imperial grandstanding of Hasilwood House and a vast empty plot for a proposed skyscraper. The church is first mentioned in 1250, with the familiar structure dating to 1411; its façade was then hidden for centuries behind two shop units. Having survived the Great Fire, St Ethelburga had to be reconstructed from rubble after an IRA bomb in 1993. Turning the other cheek, the church reopened as a peace and reconciliation centre. It is mildly startling to approach the church’s rear entrance and discover a small courtyard occupied by a large polygonal tent. Made in Saudi Arabia, the tent was officially opened by Prince Charles. Brown and white goatskin covers its sixteen sides, and the seven windows hold stained glass; the design deliberately excludes religious symbolism and is based on ‘sacred geometry’. The effect is somewhere between a gazebo, a nomadic dwelling on the steppes and a wedding reception marquee. As a venue for inter-faith dialogue its purpose is to provide a neutral and unfamiliar space that will open people’s minds, man. This sounds nauseating to me, but I come from Belfast, where it is hard not to be cynical about the Conflict Resolution industry.

BETHNAL GREEN

E. PELLICCI

332 Bethnal Green Road, E2 0AG

The rise of coffee chains has largely eradicated their forefathers, the Formica cafés established by Italian families in the 1950s. In recent years, cherished institutions of the West End such as Lorelei and the New Piccadilly Café have been banished to memory. Further east, one classic café has been saved by the bestowal of Grade II listing; this is E. Pellicci on Bethnal Green Rd, still run by the family that opened it several generations ago. The café has been here since 1900 and was a meeting place for the Kray twins. Its façade consists of panels of custard-yellow Vitrolite. Inside, seven small tables are packed into a low-ceilinged room whose walls are panelled with beautiful marquetry: rising suns around the counter and art-deco fan shapes elsewhere. Sensitive modern additions include a Pellicci logo in stained glass on the kitchen door. These cafés introduced post-war Britain to a continental influence and a strong design aesthetic. Many credit them with lifting the country out of drab austerity by providing a breeding ground for youth culture and the swinging sixties. It would be a great loss not to preserve the handful that are left.

MILE END

NOVO CEMETERY

Queen Mary College, E1 4NS

The middle of a busy university campus is an odd place to find a Jewish cemetery. The flat rectangle of land, maybe half the size of a football pitch, does not look particularly pleased about the industrial-looking building whose curved steel frame looms over it. The Novo (new) cemetery has served Sephardic Jews of Spanish and Portuguese origin since 1733; they arrived after Cromwell scrapped a centuries-old law forbidding Jews to live in England. By 1936 the cemetery was filled to capacity, and the expanding Queen Mary campus began to encroach on its grounds. Three quarters of the graves were moved to Essex, at which point the university realized that they were ripping up history and decided to preserve what was left. Today, the cemetery is a peaceful spot. Its perimeter is marked by rust-metal sheets, the name and date of the site cut into them with a stencil font that recalls the street signs of Venice, site of the first Jewish ghetto. The long gravestones lie horizontal, death literally acting as the great leveller. Poking up through the gravel are several thousand Spanish bluebells, whose soft colours compensate for the surroundings.

LEYTONSTONE

HITCHCOCK MOSAICS

Leytonstone Station, Church Lane, E11 1HE

A prophet has no honour in his own country: on the continent, Alfred Hitchcock is regarded as a classic auteur who commanded the studio system to serve his disquieting studies in obsession and madness; on these shores he is slightly misunderstood as a maker of jaunty whodunnits. In 2001, his old manor of Leytonstone attempted to redress this by installing seventeen mosaics in the exit to the Tube station. The shower from Psycho, the bell tower from Vertigo, Cary Grant fleeing a crop-dusting plane or sneaking across a Riviera rooftop – all your old favourites are there. It may not be high art but it’s fun trying to identify each scene, and honouring Hitchcock over E11’s other favourite son, David Beckham, is to be applauded. The mosaics are in an Imperial Roman style; the effect is dissonant, but gives them a blast of primitive energy. Assailed by crows, the blonde locks of Tippi Hedren become those of a shrieking Medusa.