IN THE TWO YEARS SINCE COOK’S DEPARTURE THERE HAD BEEN AMPLE TIME for Banks to regret his impetuous withdrawal. The northern expedition, intended as a prelude to his own Pacific voyage, had occupied the summer and autumn of 1772. After a leisurely passage in the Sir Lawrence, he and his party spent a fortnight in the Hebrides and by the end of August reached their chief objective, Iceland. On first landing, Banks, in the manner of southern navigators, wooed the somewhat timid fisher folk with gifts of ribbon and tobacco while Dr. Lind dispensed doses of physic and shocks from an electrical machine. Cordial relations were soon established and until late October the visitors toured the countryside, seeking out the natural wonders in which the island abounded. They examined lava fields and hot springs and spouting geysers, they climbed to the crater of Mount Hecla. And everywhere with customary zeal Banks collected mineral and botanic specimens, antiquities, books, manuscripts. Presents were exchanged and entertainments arranged on both sides. The Englishmen diverted their guests with the playing of French horns; the Icelanders sang their traditional songs, recited complimentary odes, and feasted the tourists on local delicacies — dried fish, sour butter, with whale and shark for dessert. To veterans of the Endeavour it was all faintly reminiscent of the Pacific. But they were of course half a world away from tropical Tahiti. As the northern winter impended, they loaded the Sir Lawrence with volcanic ballast, packed up their trophies, and made for home.1

Banks showed no urgent desire to reach London. He called at the Orkneys on the return voyage, may have visited the Highlands, and certainly stopped at Edinburgh. In that lively intellectual capital he and Solander met notabilities and discussed their travels, past and projected. One episode is recorded with tantalizing brevity in the journal of James Boswell: ‘Went with Dr. Solander and breakfasted with Monboddo, who listened with avidity to the Doctor’s description of the New Hollanders, almost brutes — but added with eagerness, “Have they tails, Dr. Solander?” “No, my Lord, they have not tails.”’2 Banks was also introduced to the erudite judge and may at this time have acquired An Account of a Savage Girl, Caught Wild in the Woods of Champagne. His copy of the pamphlet bears an inscription stating that Lord Monboddo had supervised the translation and ‘chiefly’ written the preface. The Savage Girl herself was one of those wild creatures so highly prized by eighteenth-century theorists. Commonly known as Mademoiselle Le Blanc, she had been found on the outskirts of the village of Songi in 1731. She was then about ten years old and wholly uncivilized in her behaviour — she ate raw flesh, climbed trees, swam like a fish, and could outrun hares and rabbits. She had since been weaned from her savage state and when Monboddo interviewed her in Paris was in corpulent middle age. In his opinion she was not, as the French supposed, of the Eskimo nation who were, he said, ‘the ugliest of men … all covered with hair’. She was probably, he thought, a member of some fair-skinned race settled near Hudson Bay, whence she had been kidnapped by an unscrupulous sea captain. Her story, he held, supported his own belief that ‘the rational man’ had grown out of ‘the mere animal’.3

With none of the fanfare which had marked his arrival from the Pacific, Banks was back in London late in November. Once the reunions and the greetings were over, his first care was for the spoils of his Icelandic tour. The manuscripts went into his library and ultimately to the British Museum; the natural history specimens and the geological samples were added to the collections at New Burlington Street; and the scoria used for ballast on the Sir Lawrence was divided between Chelsea and Kew. Since boyhood Banks had frequented the Apothecaries’ Garden near his mother’s home at Chelsea. Now he began his long association with the gardens at Kew and — perhaps on the gift of volcanic rock — laid the foundation of his friendship with their royal proprietor. At about this time he and Sir John Pringle persuaded George III to send one of Kew’s under-gardeners, Francis Masson, to collect plants at the Cape of Good Hope. Royal patronage and public funds were not forthcoming, however, for a cause that touched Banks more closely. Before the end of winter he knew that his plans for a Pacific expedition — uncertain at best — would not be realized. Yet some prospect of distant travel still remained. There was a possibility that in the coming summer he might join Constantine Phipps in a search for the North-west Passage. Meanwhile in the company of another aristocratic friend, Charles Greville, he consoled himself with an excursion to Holland.4

The contrast with the volcanic mountains and thermal wonders of Iceland could scarcely have been more marked — unless in the tropical Pacific. Banks now found himself, as he wrote to Sarah Sophia, in a ‘fenny muddy country’ that reminded him of his native Lincolnshire. Equally striking was the contrast between the simple Icelandic community and the circles in which he and Greville moved in their progress through the Dutch cities. They paid their respects to the Prince of Orange at the Hague, they sampled the opera and other diversions at Amsterdam, they met scientific literati in Rotterdam, they sought out collections and called on dignitaries in Leyden, Haarlem, Utrecht. One link with the north was a ‘Levee’ specially arranged so that Banks might meet Greenland captains and pick up information for use in Constantine Phipps’s approaching Arctic expedition.5

He appreciated these and similar courtesies, he decided the Dutch had been ‘civiler’ than he deserved, but his thoughts kept turning back to the South Seas. In Amsterdam he discussed with a Mr. Bourse, ‘advocate to the East Indies Company’, the Endeavour’s voyage, more particularly its passage through the Dutch islands.6 And ‘to amuse the Princess of Orange’ he prepared a long discourse ‘On the Manners of the Women of Otaheite’. He was evidently in a relaxed mood at the time and wrote with an enthusiasm recalling Bougainville’s initial raptures rather than the measured observations of his own voyage journal. In that island (to summarize his often incoherent superlatives), Love was the Chief Occupation, the favourite, nay almost the Sole Luxury of the Inhabitants, and both in body and soul the women were modelled with the utmost perfection. European ladies might surpass them in complexion, Banks conceded, but in all else they excelled — nowhere else had he seen their equals. Forms like theirs existed here only in marble or on canvas, were indeed such as might defy imitation by ‘the Chizzel of a Phidias or the Pencil of an Appeles’. Their figures were not squeezed by a cincture ‘scarce less tenacious than Iron’ nor swelled out below by ‘a preposterous mountain of hoops’. Their garments hung ‘in folds of the most Elegant & unartificial forms’ like, those seen on antique statues or on the angels and goddesses of the best Italian painters. Their appearance, he went on, was not a little aided by their freedom from European ideas of propriety. A Tahitian maiden would by a motion of her dress disclose an arm and half her breast, then a moment later bare the whole breast — ‘all this with as much innocence & genuine modesty as an English woman can shew’. In this ‘Land of Liberty’ chastity was nevertheless ‘Esteemd as a virtue’ and women were no less ‘inviolable in their attachments’ than in Europe. He absolved them from blame for the practice of infanticide (which he ascribed to the selfishness of their men) and in describing their domestic routine indulged in further superlatives. In cleanliness, he held, these people excelled ‘beyond all compare all other nations’, while the climate of their island he believed to be ‘without Exaggeration the best on the face of the Globe’.7

By the end of March Banks had returned home to face the inclemencies of an English spring and, as the weeks passed by, must decide on the goal of his now customary summer excursion. In the end he set off on a botanizing trip to Wales with a party that included Solander and a new friend, Dr. Charles Blagden of Edinburgh. He had toyed with the idea of visiting the Mediterranean and given more serious thought to joining Constantine Phipps in his northern voyage. In April he wrote with proprietary air: ‘we are employd in fitting out an expedition in order to penetrate as near to the North Pole as Possible ….’ A month or so later he had decided not to accompany his friend, but for the benefit of Phipps and his assistants supplied spirits, bottles, pins, snippers for the preservation of specimens, and special paper for the drying of plants. With elaborate instructions for their use he sent more general remarks. All kinds of northern animals would be curious, he observed, and, if it were possible to bring home a live white bear, he would be particularly glad. Likewise he much wished to see any seal differing from the common sort; the complete skin with the head and teeth should be procured. Since naturalists were almost totally unacquainted with whales, he went on, the foetuses of any species would be very acceptable. And so in similar strain for page upon page of admonition and advice covering the wide range of natural history. Early in June Phipps sailed in the Racehorse, while later in the month Banks departed on his more limited travels.8 Though Arctic regions might be a promising field for scientific study, he had apparently concluded, they were not for him — and provided no substitute for the South Seas.

THE DENIZENS OF THE NORTH, if neither as ugly nor as hirsute as Monboddo claimed, could certainly not compare in comeliness or romantic appeal with the paragons of Tahiti. In December 1772 a party of Eskimos reached England, brought from Labrador by the fur trader and naturalist George Cartwright. Their leader was a priest, Attuiock by name, who had with him his wife and child, a younger brother Tooklavinia, and the latter’s wife Caubvick. For a brief season the Eskimos were minor lions in learned and fashionable London. They dined with members of the Royal Society, they met the renowned anatomist John Hunter, they visited the opera and Drury Lane where they sat in the Royal Box, they watched the King review his troops in Hyde Park, and towards the end of their stay they were presented at Court. Interest in the visitors was not confined to such exalted circles. On landing at Westminster Bridge they were immediately surrounded by a curious crowd and so great was the press of people at their lodgings that Cartwright was forced to take a furnished house and limit callers to two days a week.9

The Eskimos’ response to the sights of the capital disappointed Cartwright, though it might not have surprised Jean-Jacques Rousseau. They were astonished at the number of ships on the Thames but took little notice of London Bridge which they thought was a great rock extending across the river. Nor did they at first show any particular interest in St. Paul’s, again supposing it to be a natural feature like the mountains of Labrador. A fortnight after their arrival Cartwright took Attuiock, disguised in European dress, for an excursion to the Tower and home by way of Westminster Bridge and Hyde Park Corner. On their return he expected the priest to speak of the wonders he had seen. Instead Attuiock sat down, fixed his eyes on the floor ‘in a stupid stare’, and at last soliloquized: ‘“Oh! I am tired; here are too many houses; too much smoke; too many people; Labrador is very good; seals are plentiful there; I wish I was back again.’”10

Banks, who had seen nothing of the indigenous inhabitants during his visit to Labrador with Constantine Phipps, seized this opportunity of filling a gap in his knowledge. After his return from Iceland Lloyd’s Evening Post reported that he and Dr. Solander had paid frequent visits to the Eskimos and expressed themselves ‘extremely well satisfied with the observations and behaviour of those people’. The Eskimos in return showed great pleasure in seeing the gentlemen as they generally carried with them presents of beads, knives, or iron tools and behaved with politeness and respect. In moralizing strain the writer went on to draw a comparison with less enlightened callers:

These ingenious Gentlemen, who are inquisitive to mark the discriminations of the human character in every part of the world, could not help taking notice of the intelligent countenance and discourse of the Priest, and of the easy carriage and civility of manners of the whole family; while by too many of their numerous visitors they are held in contempt as Savages, because their heads have not undergone the operations of the Friseur, and gaped at as monsters, because their dress is not according to the Bon-Ton.11

Until he left for Holland Banks evidently continued to call on the Eskimos and commissioned a number of portraits, among them two fine pastel drawings by Nathaniel Dance showing Attuiock and Caubvick in their own costume. In February Cartwright took the family to his father’s home in rural Nottinghamshire where they soon revived in health and spirits. The men marvelled at the flatness of the countryside and became keen fox-hunters, while the women, ‘according to the universal disposition of the fair sex’, enjoyed visiting and dancing. When they set out for Labrador early in May, Cartwright noted that they were well pleased in the expectation of soon seeing their native country, their relations, and their friends; he himself, he added, was very happy in the prospect of carrying them back, apparently in perfect health. His mood of self-congratulation was short lived. On the evening of their departure Caubvick complained of a sickness which was finally diagnosed as smallpox. The malady gradually spread to her companions, forcing Cartwright to delay the voyage and turn back to Plymouth. Thence early in June he left for a hurried visit to London, only to inform Banks on his return that the whole party, except for the younger woman, had now died. ‘I last night ventured to tell Caubvick of the death of all the rest, having prepar’d her for it this week past,’ he wrote, ‘she was a good deal affected, but not so much as I expected.’12

The lesson of this tragic episode was not lost on Banks whose association with the Eskimos had already supplied the pretext for a long, flattering, consoling letter from a Scottish admirer met in Edinburgh during the return journey from Iceland. ‘You will perceive, from the slight occasion on which I write to you, how desirous I am to revive a connection, the forming of which I shall ever reckon among the fortunate & agreeable circumstances of my life’, began the eminent historian William Robertson. He had read in the papers of Mr. Banks’s visit to the Labrador family, he explained, and now sought light on a question that perplexed him: Did the Eskimos, in common with all other natives of America, grow hair only on the head or were they, as rumour would have it, bearded like the inhabitants of northern Europe? He then expressed his concern over the projected (and apparently abandoned) southern expedition. ‘I look with impatience into every News Paper to learn something about your future motions’, he informed Banks. ‘What a shame it is that the first literary & commercial nation in the world should hesitate a moment about encouraging the only voyage which in modern times, has no other object but the advancement of science.’13

News of literary Edinburgh followed, in particular the recent publication of ‘a book on the origin & progress of language by Lord Monboddo, one of our Judges’. This work, as Robertson summarized it, held that men were originally quadrupeds; that several ages elapsed before they acquired the art of walking erect; that they were naturally without language; that the orang-outangs were men still in this state; that there were men with tails. ‘Amidst all these oddities,’ he commented, ‘there are mingled ingenious & bold opinions; & the book is not destitute of considerable merit.’ ‘You are frequently mentioned in it & in a proper manner’, he told Banks. The amiable Robertson ended with compliments to Solander and a reference to the approaching publication of Hawkes-worth’s narrative of their South Seas voyage: ‘I long for the month of April when we are to be entertained & instructed. If you knew how many foolish & lying books of travel I have read, you would not wonder at my impatience.’14

HAWKESWORTH’S COMPILATION was in fact delayed until the summer, appearing only after Monboddo’s speculative heresies had reached the London public. In its ‘Catalogue of New Publications’ for May 1773 the Gentleman’s Magazine listed Of the Origin and Progress of Language, Volume I, published by Cadell and sold for six shillings. The magazine made no further reference to Monboddo’s work, but for the benefit of its more studious subscribers the Monthly Review noticed it in two lengthy articles illustrated in the lavish eighteenth-century fashion with copious quotations. Though the book contained some fanciful and reprehensible ideas, remarked the anonymous reviewer, its author had read and thought much upon his subject. Few readers — indeed he ventured to say very few — would not find some things new and many others both entertaining and instructive. These would, in great measure, atone for its faults — and here he instanced the ‘pompous and unnecessary display of metaphysical knowledge’, the ‘bigotted attachment to the Greek philosophy’, and the account given of the orang-outangs. Upon the whole and in spite of such blemishes, he concluded (unconsciously echoing William Robertson), the work had ‘a very considerable share of merit’.15

One of the book’s incidental merits in the eyes of its first readers may have been a certain topicality. To supply a basis for his linguistic theories, Monboddo set out to define ‘the original nature of man’ and that, he asserted, would be found not in civilized nations but among barbarous peoples. A professed admirer of that ‘author of so much genius’, ‘Mons. Rousseau’, in describing primitive society he cited similar sources to those used two decades earlier in the Discourse on Inequality and often gave the same examples. With even greater diligence than his mentor he had combed through classical writers — Aristotle, Herodotus, Pausanius, and the obscure Diodorus Siculus, authority on the naked fish-eaters of Arabia. He had consulted later travellers for descriptions of the Hottentots and the orang-outangs whom, with more certainty than Rousseau, he classed as human beings. Again following the master, he listed European savages — the fourteenth-century child from Hesse-Cassel, the Lithuanian found in 1694, the Hanoverian brought to England in the time of George I, and one of particular interest to himself, the girl ‘catched wild in the woods of Champaigne’ and later known as Mademoiselle Le Blanc. He drew on missionary records for details of North American Indians and on a history of the Incas for his account of the aborigines of Peru. But, Monboddo pointed out, so great had been the changes since the time of Columbus it was not in the Americas that people living in the natural state must now be sought. It was in other regions as yet imperfectly discovered — ‘the countries in the South sea, and such parts of the Atlantic ocean as have not been frequented by European ships’.16

What, then, was the nature of human society in this untouched quarter of the world? Monboddo’s answer, based for the most part on the voyage narratives gathered by de Brosses, was scarcely reassuring to Utopia-seekers. William Dampier met in New Holland naked fishermen exactly like those described by Diodorus Siculus. Amerigo Vespucci lighted on a people living together in herds without government, religion, arts, or property. Jack the Hermit wrote that the Fuegians acted entirely like brutes with no regard for decency. Narbrough found cannibals, Le Maire savages who bit like dogs …. So, in anticipation of later armchair anthropologists, Monboddo assembled his highly selective, carefully documented evidence, culminating in the revelation that brought him lasting notoriety. He himself made no claim to have discovered men with tails. That, he observed, was a fact not only attested by Linnaeus and Buffon but (here again following Rousseau) one that was borne out by the satyrs of ancient mythology. His own modest contribution was to quote from Keoping, a Swedish traveller, who saw in Nicobar ‘men with tails like those of cats’. As Monboddo emphasized, he accepted this ‘extraordinary’ assertion only after an exchange of letters with Linnaeus, and for the benefit of sceptical readers he quoted the correspondence in a footnote.17

Monboddo passed cursorily over recent Pacific voyages. He seems to have taken from Bougainville’s published narrative some details of the Falkland Islands. The same source may have supported his view that a golden age, the ‘poetical fiction’ of the ancients, still existed in the South Seas. There was, however, no specific mention of New Cythera and none of Aoutourou. Similarly — and despite William Robertson — references to Banks were few and perfunctory. He and Solander were credited with finding in New Zealand people who fed on human flesh but who, far from being ‘barbarous or inhuman’, were ‘brave and generous’. Another passage, apparently inspired by a meeting with Banks in Edinburgh, praised his enterprise and linguistic skill. But that was all. When he brought this section of his work to a close, Monboddo was in a mood of inquiring anticipation shared by other members of the learned and literary world. Having summed up his findings on ‘the natural state of men’ in southern regions, he went on: ‘we have reason to expect from those countries, in a short time, much greater and more certain discoveries, such as I hope will improve and enlarge the knowledge of our own species as much as the natural history of other animals, and of plants and minerals.’18

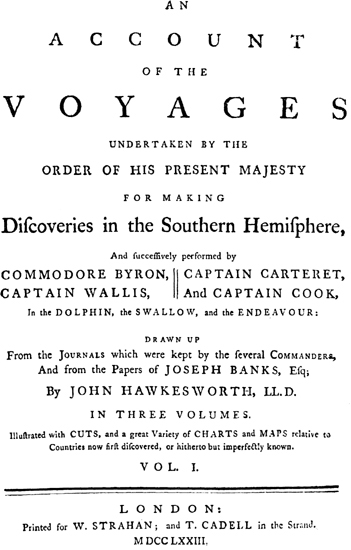

If the allusion was to Hawkesworth’s narrative (and not to Cook’s latest voyage or to the abortive plans of Banks), it appeared not in the spring of 1773, as Robertson had hoped, but in the following June. Even so, its publication was a remarkable achievement on the part of those concerned — printers, artists, draughtsmen, binders, and, above all others, the compiler. Hawkesworth had fully justified Dr. Burney’s recommendation and carried out his commission with business-like efficiency. From a mass of routine day-to-day records — not only Cook’s but those of his predecessors and their subordinates — he had selected the more important and given them consecutive form. He had ingeniously combined the observations of Cook and Banks, acknowledging the latter’s help on the title-page and also in a preface. He had, according to his own testimony, consulted all the major contributors. And within two years of the expedition’s return he had completed An Account of the Voyages undertaken by the order of His Present Majesty for making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere. A dedication to the monarch credited him with possessing ‘the best fleet, and the bravest as well as most able navigators in Europe’. It was further claimed that the discoveries made under His Majesty’s auspices were ‘far greater than those of all the navigators in the world collectively, from the expedition of Columbus to the present time’. The work was presented in three quarto volumes, the first describing the voyages of Byron, Wallis, and Carteret, the second and third Cook’s.19

When replying to his critics, Hawkesworth modestly claimed to have been ‘little more than an amanuensis for others’. He was of course something far different. He was a professional man of letters guided by his own principles and the editorial conventions of his time. In working on the voyages his object was to create a continuous narrative that would at once record, instruct, and entertain. He relied on his sources for facts and dates, but in other respects he felt himself at liberty to modify, add, or omit as taste and literary considerations demanded. Hence he did not hesitate to convert the language of untutored seamen into his own measured prose nor to subject the journal of Banks to the same unifying process. A further device, also tending to unify, was discussed in his introduction. To bring ‘the Adventurer and the Reader nearer together’ and so, he explained, ‘excite an interest, and … afford more entertainment’, he had written not in the third person but in the first.20 The result was the creation of an Adventurer, brave and benign, persisting from voyage to voyage and expressing himself in sub-Johnsonian English. Moreover, since the author-compiler had felt himself free to introduce his own ponderings and opinions, the Adventurer was endowed with the gift of sententious utterance. This was the dominating figure in Hawkesworth’s epic of British enterprise in the South Seas.

23 Hawkesworth’s epic of British exploration

Like other epic heroes, the British Odysseus journeyed for a purpose. But since the search for a southern continent had been fruitless (and was in any case of little interest to Hawkesworth), this aim was relegated to a minor place. With a certain inevitability and for a variety of reasons — historical, geographical, literary — Tahiti became a focal point of the narrative. In the opening volume, following Byron’s unsuccessful quest, Wallis in the guise of the Adventurer discovered the island, subdued its people, and won over its ‘Queen’ whose dramatic possibilities Hawkesworth was quick to recognize and exploit. Then in the climactic second volume came the protracted sojourn of Cook-Odysseus and his companions, the reappearance of the Queen, now endowed with the poetic name of Oberea, and the expedition’s departure, bearing away her favourite Tupia. In both episodes, but especially in the later one, the attractions of Tahiti were thrown into relief by the prelude and the sequel. Before reaching this haven of ease and plenty the navigators had experienced the hazards and discomforts of a long voyage; on leaving it they suffered even greater dangers and privations in the uncharted waters of the Pacific. The contrast with exotic peoples encountered elsewhere was equally striking. Whatever their shortcomings, the Tahitians seemed a world apart from the forlorn natives of South America or the naked inhabitants of New Holland.21

Hawkesworth’s picture of Tahiti was thus generally favourable. But he gave no more support than Banks did to the view that the island was a tropical paradise populated by survivors from a golden age. Indeed, while retaining Banks’s early impression of the ‘Arcadian’ appearance of Matavai Bay, he dropped other more fanciful allusions: the classical names originally conferred on local dignitaries, for example, or the comparison of wandering bards, the arioi, with Homer. Where he did not hesitate to follow Banks, his chief source for the later expedition, was in the emphasis given to erotic behaviour. The scene of the naturalist’s confrontation with Oberea and her lover was seized upon and filled out with improbable details. (Banks was shown modestly withdrawing to the adulterous queen’s ‘antichamber’.) An account of the fertilization ceremony performed by young women was taken over from his journal and, since he had made no mention of the public act of copulation witnessed near Fort Venus, a version of the incident was drawn from the usually reticent Cook. So Hawkesworth provided diversion of a titillating kind for his readers, but his aim was to instruct as well as entertain. In the stern role of moralist he did not hesitate to condemn the islanders’ ‘dissolute sensuality’ nor to hint darkly at vile customs which ‘no imagination could possibly conceive’. Elsewhere he censured openly or by implication their thievishness, their savagery in warfare, and the inhuman practice of infanticide prevailing among their arioi.22

The mouthpiece for Hawkesworth’s moralizing on the Tahitians was the Adventurer represented by Cook who was shown holding himself somewhat aloof from the spectacle of island life. He was leader, commentator, dispenser of justice, and only to a limited degree an active participant. The role of Banks was markedly different, the result partly of the recorded facts, partly of their literary manipulation. Hawkesworth was grateful to the botanist for so generously permitting the use of his ‘accurate and circumstantial journal’ and expressed his thanks in effusive terms. On reading the document, however, he must have realized that it sometimes disclosed the writer in an unflattering and even compromising posture. This scion of the landed gentry had mingled freely with uncivilized natives; he had pried in most ungentlemanly fashion into their customs; he had on one occasion shed his clothes and blackened his person in the process; and he had, it was obvious, enjoyed the favours of island women. How, then, should this potentially damaging material be treated? Hawkesworth chose the path of discretion. He eliminated explicit allusions to the young man’s amours; he justified his undressing and body-smearing on the grounds that ‘he could be present upon no other condition’; and he modified the account of his relations with Oberea, omitting, for instance, all reference to her rejected overtures. Nevertheless, in spite of Hawkesworth’s efforts, the censored narrative contained enough to establish Banks’s reputation as an unconventional and sometimes comic figure. He had begun his long career in the annals of the expedition as a foil to the heroic and dignified Cook.23

Where Hawkesworth did less than justice to Banks and the other ingenious gentleman was in the limited use he made of their contributions to natural history. In his final account of Tahiti he disposed of animals, birds, and fishes in a few perfunctory lines. A further paragraph listed plants and trees, but there was no consistency in nomenclature and the catalogue was filled out with the misleading comment, derived from Banks: ‘the inhabitants … seem to be exempted from the first general curse, that “man should eat his bread in the sweat of his brow.”’24 Similarly a number of the plates tended to support an idyllic conception of island life that Hawkesworth had been at pains to discount in his narrative. Some illustrators confined themselves to representations of native artifacts or straightforward landscapes based on the work of Banks’s lamented draughtsmen. Others drew to a greater or lesser extent on the imagination: one engraver, Woollett, emphasized the sombre and sometimes sinister atmosphere of Parkinson’s sketches; a second, Rooker by name, saw the Tahitians through a haze of Graeco-Roman myth. But idealization in terms of the classical European past was carried to an extreme by the artist Cipriani and his engraver Bartolozzi in what purported to be the view of an interior in Raiatea. Accompanied by the music of a nose-flute, lightly robed maidens danced in a pillared atrium before an audience arrayed in the togas of ancient Rome.25

This and a similar plate (showing the ‘wretched’ inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego) moved the Monthly Review to mild protest. Truth and nature, it complained, had been sacrificed to the painter’s ideas of grace and beauty. Cipriani’s elegant pencil had depicted not South Sea Islanders but figures which continually reminded the spectator of the antique or productions of the Roman and Florentine schools. It was one of the few adverse comments in a series of articles that ran through four numbers of the periodical late in 1773. The writer, on the evidence of his style and preoccupations, was probably that philsophical reviewer who in his notice of Bougainville had looked forward to the impending appearance of Hawkesworth’s volumes. If so, his expectations were not disappointed. Ever since the discovery of America was completed, he remarked, there had been speculation on the state of ‘that immense … part of the terraqueous globe’ lying between the southern extremity of the new world and the Cape of Good Hope. The peculiar air of secrecy surrounding recent expeditions had excited new attention, while some imperfect and anonymous reports had served rather to provoke than satisfy the public’s curiosity. Now they had the authentic account, abounding in curious information and, notwithstanding certain imperfections, adorned both in sentiment and diction by the editor’s pen.26

The reviewer passed lightly over Hawkesworth’s imperfections. He conscientiously surveyed each expedition, selecting for special attention those of Wallis and Cook; and from the immense expanse of the terraqueous globe he chose for extended treatment Tahiti and its unique inhabitants. Few nations (to summarize his scattered observations) had been discovered whose manners and customs carried such an air of singularity. Indeed, in government and habits they appeared to be nearly as much the antipodes of Europe as in their geographical situation. And nowhere was their conduct more truly paradoxical than in their attitude towards ‘a certain appetite’. Among these people, both male and female, the very idea of chastity seemed unknown. Such were their enlarged notions that the gratification of bodily desires never gave rise to scandal. Nor was the act performed with any degree of secrecy — and here Banks’s ‘blundering’ confrontation with Oberea and her youthful lover were cited: ‘Our Otaheitean Princess appears to have been no more disconcerted … than if he had interrupted her at breakfast ….’ The ‘supposed sovereign’, this lady ‘d’un certain age’, had obviously captured the writer’s imagination. He had already expended pages in describing her relations with Wallis and in illustrating her dignity, her generosity, her extreme sensibility. She seemed to have had ‘a most tender attachment to our adventurers’, he noted, and to have been ‘as susceptible as Queen Dido’.27

The comparison prompted melancholy ponderings on the recent history of these ‘men of nature’ hitherto so widely severed from the rest of the world. Though Oberea’s fate had been less tragical than the Carthaginian queen’s, she too had suffered misfortune. On landing at Matavai Bay, Banks and his companions found that romantic spot a scene of devastation. After the Dolphin’s departure, they soon learned, the island had been ravaged by a war which had dislodged Oberea and her consort from the seat of power. What, asked the philosophical reviewer, was the origin of this conflict? In seeking an answer he had recourse to the Discourse on Inequality:

The people of Otaheite, in the state in which they were found by our countrymen, present us with a picture of human society resembling, in more respects than one, that which the ingenious but fanciful Rousseau has delineated, when he exhibits a view of what he terms the ‘real youth of the world:’ — a state which he considers as the best for man; all the ulterior supposed improvements of which ‘have been so many steps tending, in appearance, towards the advantage of individuals, but in fact towards the deterioration of the species.’ It is ‘Iron and Corn,’ our philosopher afterwards observes, ‘that have civilized men, and ruined mankind.’

Rousseau’s thesis appeared to find some support in the pages of Hawkesworth. True, the Tahitians were already tolerably civilized and divided into classes. But the introduction of European novelties, particularly iron, had increased existing inequalities and sown the seeds of war. Furthermore, this hitherto healthy race had been infected with ‘a certain loathsome disease’ — not by the English but, according to Bougainville’s own testimony, by the French. On this reassuring note the reviewer left Tahiti to dwell more summarily on the subsequent discoveries of Cook and his ‘philosophical adventurers’.28

The Gentleman’s Magazine showed its approval of Hawkesworth’s compilation in its own lavish fashion. From June 1773 until March 1774 it issued a series of ‘epitomes’ so elaborate that a parsimonious reader might have regarded them as a substitute for the published work and saved himself an outlay of three guineas. Each of the expeditions was described in detailed articles filled out with excerpts from the original. Comparisons were sometimes made with other voyagers — Anson, Alexander Selkirk, Bougainville — but editorial asides were infrequent and critical comments even fewer. The anonymous writer found the account of Oberea’s parting with Wallis reminiscent of the scene between Dido and Aeneas and suspected that Hawkesworth might have drawn his tenderest strokes from Virgil. Citing both Wallis and Bougainville on the vexed question of venereal disease, he positively asserted: ‘the crew of the Dolphin did not communicate it.’ He lamented the death of Tupia, ‘perhaps, the most intelligent Indian’ in the island, who, had he survived, would ‘probably have enlightened Europe with a new species of learning’. Further, he regretted that Cook had not left the two deserters at Tahiti to introduce civilized arts among the inhabitants and give them ‘higher notions of the Supreme Being’. Hawkesworth’s narrative of the final expedition occupied at least half the reviewer’s space and inspired his highest praise. There was not, he claimed, ‘in any language, a voyage so full of variety, and so elegantly written.’29

An eager public evidently agreed with the reviewer’s verdict. The work was an immense popular success from the outset and soon ran into a second edition. By the close of 1773 it had been separately published in Dublin, and before another year was out versions had appeared in New York, Berlin, Rotterdam, and Paris.30

READERS IN TWO CONTINENTS AND TWO HEMISPHERES might marvel at Dr. Hawkesworth’s eloquent revelations, but the pundits of literary London were not impressed. The supreme pundit, indeed, condemned his old friend’s work before it actually appeared. Boswell records this sparkling exchange in May 1773, prompted by a reference to the forthcoming publication:

JOHNSON: ‘Sir, if you talk of it as a subject of commerce, it will be gainful; if as a book that is to increase human knowledge, I believe there will not be much of that. Hawkesworth can tell only what the voyagers have told him; and they have found very little, only one new animal, I think.’ BOSWELL: ‘But many insects, Sir.’ JOHNSON: ‘Why, Sir, as to insects, Ray reckons of British insects twenty thousand species. They might have staid at home and discovered enough in that way.’

Horace Walpole at least had the grace to read the book before belittling it with aristocratic disdain. The new Voyages, he remarked on 21 June, ‘might make one a good first mate, but tell one nothing at all.’ Dr. Hawkesworth, he went on, was still more provoking:

An old black gentlewoman of forty carries Captain Wallis across a river, when he was too weak to walk, and the man represents them as a new edition of Dido and Aeneas. Indeed, Dido the new does not even borrow the obscurity of a cave when she treats the travellers with the rites of love, as practised in Otaheite.

A fortnight later he had almost ‘waded through’ the three volumes to reach the conclusion: ‘The entertaining matter would not fill half a volume; and at best is but an account of the fishermen on the coast of forty islands.’31

Published attacks were at once more specific and more forceful. A contributor to the Gentleman’s Magazine severely censured the author-editor not only for his ignorance of the arts of navigation and astronomy but for failing to attribute the Endeavour’s survival on the coast of New Holland to God’s special interposition. His heretical views on the nature of Divine Providence were again the target of an anonymous pamphleteer who asserted that by denying the possibility of such intervention Dr. Hawkesworth had lost ‘his literary fame, and the esteem of mankind’.32

Most vehement of the critical pack, however, was Alexander Dalrymple. Still outraged that not he but the unlettered Lieutenant Cook had taken charge of the Endeavour, this contentious Scot set out to refute Hawkesworth’s ‘groundless and illiberal Imputations’ in a Letter littered with italic type and illustrated with voluminous excerpts from his previous writings and those of Pacific navigators. He demolished Hawkesworth’s charge that he — Dalrymple — had misrepresented the records of Spanish and Dutch voyages in order to support his own conjectures; he disclosed discrepancies between the published charts and corresponding sections of Hawkesworth’s narrative; he denounced the plates on both moral and artistic grounds; and he deplored those malign influences in the Admiralty which had prevented him from commanding the Endeavour and Mr. Banks from setting out in the Resolution. Although four voyages had now been made, he pointed out in a ‘Postscript to the Publick’, it was not yet determined whether or not there was a ‘SOUTHERN CONTINENT’. ‘… I would not have come back in Ignorance’, he concluded.33

25 The first in a long series of verse satires

In the preface to his second edition, Hawkesworth made some attempt to answer Dalrymple, employing the basest of all controversial weapons, ridicule. ‘I am’, he wrote, ‘very sorry for the discontented state of this good Gentleman’s mind, and most sincerely wish that a southern continent may be found, as I am confident nothing else can make him happy and good-humoured.’ The irrepressible Dalrymple in his turn replied in further Observations which he printed but did not publish out of respect for his late opponent’s memory. For Dr. Hawkesworth died in November 1773, the victim in Fanny Burney’s opinion less of the ‘lingering fever’ to which his end was publicly attributed than of persecution from ‘those envious and malignant Witlings’ of the literary world.34

Dalrymple might fairly be described as envious but scarcely as malignant and certainly not as a witling. In all probability Miss Burney referred not to his ponderous diatribe but to a work that exploited the satiric and erotic possibilities of Hawkesworth’s volumes. A pseudonymous writer, reputedly Major John Scott, seized upon two themes — the moral lapses of the voyagers (Banks in particular) and the licentious customs of Tahiti — which he elaborated in what proved to be the opening number of a verse cycle varied both in authorship and subject. An Epistle from Oberea, Queen of Otaheite, to Joseph Banks, Esq., though dated 1774, appeared in the previous year, purporting to be a translation from the Tahitian language. Like reviewers and commentators before him, the writer saw Oberea as a Dido of the South Seas and shows her bereft of her lover Banks, known to her as Opano:

Read, or oh! say does some more amorous fair

Prevent Opano, and engage his care?

I Oberea, from the Southern main,

Of slighted vows, of injur’d faith complain.

Throughout the lament the author introduced references to practices and topics familiar to newspaper readers ever since the Endeavour’s return — the promiscuity of Tahitian women, their curious habit of tattooing the buttocks, the prevalence of venereal disease (inevitably attributed to French influence) — together with further customs and incidents described in the recently published narrative. The mock-heroic treatment was matched by a mock-scholastic apparatus of footnotes and references culled from both classical writers and Hawkesworth (whose ‘pruriant imagination’ was openly censured). In heavily facetious vein the author announced the early publication of a Tahitian grammar and dictionary uniform in format and price with Hawkesworth’s Voyages.35

The effect of this usually good-humoured, if rather tasteless, exercise could scarcely have been lethal in itself, though it might have contributed to the anxieties that beset Dr. Hawkesworth towards the end of his life. His death wholly silenced the witlings, according to Fanny Burney, but not this versifier or (as the authorities assert) one of his imitators. Late in 1773 or early the next year there appeared An Epistle from Mr. Banks, Voyager, Monster-hunter, and Amoroso, to Oberea, Queen of Otaheite. An appropriately reflective note was sometimes introduced into the new monologue, as when Banks-Aeneas confessed that in seducing Oberea he was to blame, for in the other hemisphere European moral notions were either non-existent or completely reversed:

Desire was mutual, but the fault was mine;

For you, fond souls, who dwell beneath the line,

In mutual dalliance hold perpetual play,

The golden age repeating ev’ry day.

What’s vice in us, in you is virtue clear,

Untaught in guilt, you cannot know to fear.

Such a passage is exceptional, however, and in general the mixture of satire and salacity is coarser than before, while criticism of Dr. Hawkesworth for the demoralizing nature of his work becomes even more explicit:

One page of Hawkesworth, in the cool retreat,

Fires the bright maid with more than mortal heat;

She sinks at once into the lover’s arms,

Nor deems it vice to prostitute her charms;

‘I’ll do,’ cries she, ‘what Queens have done before;’

And sinks, from principle, a common whore.36

The cycle plumbed new depths with the next contribution, ‘An Heroic Epistle from the injured Harriot, Mistress to Mr. Banks, to Oberea, Queen of Otaheite’, published anonymously in the Westminster Magazine for January 1774. Banks’s rejected fiancée, Harriet Blosset, was dragged from rural seclusion and endowed not only with the manners and vocabulary of a fishwife but with some classical erudition. Oberea is by turns ‘savage Slut’, ‘wanton Gypsy’, ‘dirty Queen’, ‘Inveigling Harlot’, ‘royal bawd’. She is likened to ‘a Gosport Jade’ or ‘lewd’ Calypso and scorned for her presumptuousness in attempting to win back Banquo or Tolano (as Banks is indifferently termed):

Think’st thou he’ll leave my European grace

For thy daub’d, yellow, dirty tatoaw’d face?

Vain OBEREA will in vain beseech,

And to the bawdy winds betray her painted breech.

The jealous virago lampoons ‘smug’ Solander, ridicules Clerke for his ‘choice of jades’, and touches on the ‘scenes obscene’ described or hinted at by ‘luscious’ Hawkesworth. In a final burst of triumphant rhetoric she draws the stock comparison:

Alas! these joys, like Dido, you have prov’d,

Like her you’ve lost the godlike man belov’d …,37

Not all the verse inspired by Hawkesworth was satiric in conception. In the spring of 1774 there appeared the anonymous Otaheite, simply characterized as ‘A Poem’. It was, in fact, an abbreviated version of that epic which Dr. Johnson had adumbrated after his first meeting with Banks. And though the botanist is not mentioned by name, his person is faintly discernible in the abstract figures who move through the opening sections of the work. He is perhaps the ‘sea-beat Wand’rer’ restored to his ‘native Soil’ after perilous travels through ‘wide Limits of the Southern World’; more certainly he is one of the ‘Sons of Science’ who have sought out ‘Tribes yet unknown … Wonders unexplor’d’; and possibly he is the ‘Sage’ whose ‘penetrating View’ dares to pursue nature to her ‘inmost Depths’. After surveying regions ‘Where Nations shiver with Antarctic Frost’, the Wand’rer reaches the poem’s nominal subject, ‘The CYPRUS of the SOUTH, the Land of Love’. Tahiti is first presented in idyllic terms:

Here, ceaseless, the returning Seasons wear

Spring’s verdant Robe, and smile throughout the Year;

Refreshing Zephyrs cool the noon-tide Ray,

And Plantane Groves imperious Shades display.

Tahitian love-making is touched on with only a hint of censure:

Impetuous Wishes no Concealment know,

As the Heart prompts, the melting Numbers flow:

Each OBEREA feels the lawless Flame,

Nor checks Desires she does not blush to name.38

But the author was no sentimental admirer of these people released by nature from arduous labour and dedicated to a life of self-indulgence. Comparing them with more virile nations, he comments disapprovingly:

A Dream their Being, and their Life a Day.

Unknown to these soft Tribes, with stubborn Toil

And Arms robust to the cultur’d Soil;

Unknown those Wants that prompt th’ inventive Mind,

And banish nerveless Sloth from Human-kind.

Yet passive indolence is among the least of Tahitian shortcomings; he next summons up the spectre of infanticide, the more awful because of the idyllic setting in which it is perpetrated:

Does here MEDEA draw the vengeful Blade,

And stain with filial Gore the blushing Shade;

Here, where Arcadia should its Scenes unfold,

And past’ral Love revive an Age of Gold!

The poet concludes by advocating that Christian morality and the truths of revealed religion should be conveyed to these benighted islanders. Prefiguring the course of future history, he urges his fellow countrymen

To bid th’ intemp’rate Reign of Sense expire,

And quench th’ unholy Flame of loose Desire;

Teach them their Being’s Date, its Use and End,

And to immortal Life their Hopes extend ….39

ON THAT NOTE OF EARNEST EXHORTATION one phase in the record of British enterprise in the Pacific came to a close. Ever since the Endeavour’s return, less than three years before, accounts of the newly discovered region had been flowing from the press in a continuous stream. Newspaper reports, with their references to exotic places and people, had roused widespread curiosity which had been whetted rather than appeased by unauthorized revelations. Bougainville’s narrative, in its English rendering, had excited further interest in New Cythera and its romantic inhabitants. The daring and often bizarre theories of Monboddo had imparted a philosophical flavour to the travellers’ tales culled from de Brosses. Next had come Hawkesworth’s three volumes where successive voyages had been placed in perspective and elevated to epic status. Following closely on Hawkesworth, Sydney Parkinson’s brief Journal had added a pathetic footnote to the annals of the Endeavour.40 Then there were verse publications — satiric or mildly salacious or meditative — with a spate of reviews, critical articles, and disputatious pamphlets. By the summer of 1774 the formerly meagre literature on the South Seas had swelled to considerable dimensions.

Banks’s response to the recent accessions, wherein he had so prominent a part, remains a matter for conjecture. He could scarcely have been unaware of the Epistle from Oberea which soon ran into several editions (one ostensibly issued in his native Lincolnshire).41 But with a dignified reticence he had not always displayed in his quarrel with the Admiralty he seems to have ignored the lampoon and its successors. On the subject of Hawkesworth’s compilation, only obscure hints of his views survive in a letter from his colleague. Writing to Lord Hardwicke, Solander commented: ‘Nothing can be more certain than that the Publication of the South Sea Voyages, at last became a perfect Jobb, which has been extreemly disagreable to Those who had in some measure a hand in it.’ He hoped (but was not sure) that in their ‘grand Natural History Work, Mr. Banks would, by way of preface, remedy Hawkesworth’s omissions. That editor’s few remarks on the customs, religion, and politics of the South Sea Islanders, he said, did ‘no credit to the Work’. As for his lordship’s observation upon the figures of Cipriani and Bartolozzi, it was, thought Solander, ‘partly just’: they had certainly made the people of Tierra del Fuego too handsome, but he was not sure they had exaggerated much in regard to the inhabitants of Raiatea and Huahine.42

Of the ingenious gentlemen’s affairs in the period following their summer excursion to Wales again little can be said. In September 1773 they learned that Constantine Phipps had returned after his unsuccessful attempt on the North-west Passage, ‘so’, Banks wrote to Sarah Sophia, ‘I am glad I was not one of the Party’. He may have been in a similar mood of self-congratulation the following month when news reached London of Marion du Fresne’s awful end: in June 1772 Aoutourou’s benefactor with more than a score of his men had been killed in New Zealand, ‘and’, as Solander surmised, ‘in all probability afforded the inhabitants a good meal.’ Banks might regret the lost delights of the south, but he was at least secure from its hazards while he laboured with Solander over the ‘grand Natural History Work’ or rusticated on his estate at Revesby Abbey or consulted with the King at Kew. He continued to win modest distinctions — election to both the Council of the Royal Society and the exclusive Society of Dilettanti. To his contemporaries, however, it might have seemed that after his brief hour of renown he had lapsed once more into relative obscurity. Horace Walpole was certainly of that opinion. On 10 July 1774 he wrote to Sir Horace Mann: ‘Africa is, indeed, coming into fashion. There is just returned a Mr. Bruce, who has lived three years in the court of Abyssinia, and breakfasted every morning with the Maids of Honour on live oxen. Otaheite and Mr. Banks are quite forgotten.’43

Four days later Captain Furneaux reached Portsmouth with his living trophy from the Society Islands. A new chapter in the history of British relations with the South Seas was about to open and Mr. Banks was on the point of enjoying a fresh measure of fame.