VIGILANT OBSERVERS CONTINUED TO FOLLOW OMAI’S MOVEMENTS AND fortunes. ‘We are informed’, announced the General Evening Post on 25 August, ‘that the native of Otaheite has undergone the operation of the small-pox much better than was expected, and will set out this week with Lord Sandwich and Mr. Banks on a tour into the West of England.’1 The still nameless native, ‘having recovered from the Smallpox’, was next reported to have dined at Sir John Pringle’s in Pall Mall on the 24th in the company of the Earl of Sandwich and several other noblemen. On the 25th, accompanied by Mr. Banks and Dr. Solander, he was observed at a Royal Society dinner held in the Mitre Tavern, Fleet Street.2 Finally came the news that he had set out on the 27th with all three patrons, not for the west but for the First Lord’s country seat at Hinchingbrooke. His lordship’s band of musicians, the notice added, had received orders to hold themselves in readiness to assist at a grand oratorio to be given in compliment to the guests. The whole would be conducted by Signor Giardini.3

To members of the Burney family, then living in Queen Square, Bloomsbury, these events and persons were of more than passing interest. As sensitive to the fluctuations of social fashion as Horace Walpole himself, Fanny had now assessed the stranger’s place in the current hierarchy. Entering her diary late in August, she wrote: ‘The present Lyon of the times … is Omy, the native of Otaheite; and next to him, the present object is Mr. Bruce, a gentleman who has been abroad twelve years, and spent four of them in Abyssinia ….’ Recently, she noted, Mr. Bruce had called at Queen Square with her friend Miss Strange and was ‘almost gigantic!’, the tallest man she had ever seen; but she could not say she was charmed with him — he seemed rather arrogant and had so good an opinion of himself that he had nothing left for the rest of the world but contempt. In her next entry, at the beginning of September, she turned to a more agreeable topic: ‘My father received a note last week from Lord Sandwich, to invite him to meet Lord Orford and the Otaheitan at Hinchinbrook, and to pass a week with him there; and also to bring with him his son, the Lieutenant.’ ‘This’, Fanny went on, ‘has filled us with hope for some future good to my sailor-brother, who is the capital friend and favourite of Omai, or Omiah, or Omy, or Jack, for my brother says he is called by all those names on board, but chiefly by the last appellation, Jack!’4

Jack he might have been on the Adventure or yet another shipboard appellation missing from Fanny’s list, Tetuby Homy, able seaman. Now he was an honoured visitor to country houses, a central figure in social functions, the guest and associate of noblemen. Early in the month the General Evening Post published an extract from a letter received from Huntingdon and dated Friday 2 September. Omai, it stated, accompanied by Mr. Banks and Dr. Solander, had spent the last week at Hinchingbrooke ‘where Lord Sandwich has given them such a reception, that the stranger cannot but form a most favourable idea of his Lordship’s hospitality.’ Nor had the neighbourhood been less eager in showing their desire to please him, the correspondent reported: he had been entertained every day with new amusements. On Monday Lord Sandwich ‘had a sailing party upon Whittle-Sea Meer, at which the Duke of Manchester, Lord Ludlow, Sir Robert Bickerton, and a great many of the Huntingdon gentlemen assisted.’ On Wednesday a grand oratorio was performed at Hinchingbrooke. On Thursday the Duke of Manchester entertained the guests at Kimbolton and that morning, Friday, Lord Ludlow was giving a fox hunt. The next day they intended seeing Cambridge and on Monday, the letter ended, they proposed to set out for the north.5

Here and there the bare facts of the press report can be supplemented from more personal sources. At an early stage of the house party Banks sent an enthusiastic note to his sister which she dutifully copied:

Omai dressed three dishes for dinner yesterday, & so well was his Cookery liked that he is desired to Cook again to day not out of Curiosity but for the real desire of Eating meat so dress’d: he succeeds prodigiously: so much natural politeness I never saw in any Man: wherever he goes he makes Friends & has not I believe as yet one Foe.6

Omai’s culinary talents, probably on the same occasion, are also referred to in the memoirs of Joseph Cradock, the musical impresario and minor man of letters. One day, he relates, Lord Sandwich ‘proposed that Omai should dress a shoulder of mutton in his own manner’, a suggestion that delighted the visitor, ‘for he always wished to make himself useful.’ A description of the procedure followed:

Having dug a deep hole in the ground, he placed fuel at the bottom of it, and then covered it with clean pebbles; when properly heated, he laid the mutton, neatly enveloped in leaves, at the top, and having closed the hole, walked constantly around it, very deliberately, observing the sun. The meat was afterwards brought to table, was much commended, and all the company partook of it.

‘And’, the writer admonished, ‘let not the fastidious gourmand deride this simple method ….’ Another anecdote, not certainly of this period (Cradock is innocent of dates and erratic in sequence), describes Omai’s response when offered ‘stewed Morello cherries’ at an ‘elegant repast’. Instantly he jumped up, quitted the room, and, on being followed, informed his companions ‘that he was no more accustomed to partake of human blood than they were.’ He continued ‘rather sulky’ for some time and was induced to return to the table only when his fellow guests helped themselves to the dish. ‘But’, wrote Cradock, ‘the most memorable circumstance, I recollect, relative to Omai, was when he was stung by a wasp.’ While the company at Hinchingbrooke was breakfasting, he entered the room in great agony, his hand ‘violently swelled’, but was unable to explain the cause. At last, not knowing the word wasp, he made them understand that ‘he had been wounded by a soldier bird’ — a definition which, in Dr. Solander’s opinion, could not have been excelled by a naturalist.7

A further contretemps appears to have marred the visit to Kimbolton, according to Miss Banks who had the news from a Miss King who, in turn from some nameless informant, ‘heard when Omai was at the Duke of Manchesters he was Electrified which frightened him so much he ran out & would not come back till my Brother persuaded him he should have no more tricks played him ….’ Sarah Sophia entered the item on 2 September with others she had gathered from her brother’s housekeeper Mrs. Hawley. Omai, asserted that lady, had been strongly advised against leaving the South Seas with the English who, his ‘King’ warned, would certainly kill him, since Tupia, Tayeto, and ‘likewise the man that went with Mr Bougainville never had returned to Otaheite.’ (But, noted the well-informed Miss Banks, the first two died of a ‘Distemper’ and the third of ‘small Pox’.) Mrs. Hawley was able to throw a little fresh light on the familiar subject of Omai’s inoculation. He misunderstood what was told him, she claimed, and thought he was never to have the illness at all, ‘in consequence of which when it came out he was very low spirited & said he should dye but was soon comforted by those about him ….’ The most startling of Mrs. Hawley’s revelations, however, combined the themes of revenge and romance: ‘Omai says he wants to return with men & guns in a Ship to drive the Bola Bola Usurpers from his property that then he would place his Brothers there return himself to England where he proposed having a Wife. a young & handsome English Woman 15 years old.’8

While Miss Banks entered her devious jottings, Omai was on the eve of further social triumphs and more extensive travels through the English countryside. Early in September the Hinchingbrooke house party broke up and Solander returned to London, leaving Banks to head north with their protégé. ‘Omai’, he wrote to Charles Blagden, ‘has now after having gone through all his Physickings absolutely recovered all the fasting &c. the consequence of the Distemper’. He himself would not be in London till the end of the month, Banks explained, for he was carrying Omai to the Leicester races and ‘from thence to Ld Hinchin-brooks in Northamptonshire’; ‘he is very much liked’, he added, ‘& I do this to make him known agreeably without his becoming a shew’.9 It was some measure of Banks’s regard for the young man that he should have forgone his usual summer botanizing to undertake this excursion. He had hoped to spend some time in the company of Constantine Phipps at Mulgrave Hall in Yorkshire. But that versatile gentleman, now engaged in electioneering, wrote to say that, though he would have been very happy to see his ‘Copper coloured friend, Omai’, he had to visit Newcastle. He thanked his dear Banks for getting him out of ‘the scrape’ (through not presenting his book to the Queen, Banks noted), said that ‘Election matters’ were proceeding well, and expressed his pleasure that they would meet in town at the latter end of October.10

In the meantime Banks must content himself with less congenial companions and more frivolous diversions. Mr. Banks and Omai were amongst the noble and brilliant company at our annual music meeting this week, announced the General Evening Post’s Leicester correspondent on Saturday 24 September. They were at all the different entertainments, dined at the ‘ordinary’ on the previous Wednesday, ‘likewise at the race ordinary’, and at night attended the assembly. ‘Omai, in particular,’ the writer went on, ‘is remarked to have behaved with great politeness, allowing for his short acquaintance with European manners; at church he saw a gentleman he had accidentally seen before at Buxton, and bowed to him with the address of a well bred European.’ At all the public functions, moreover, ‘he sat with ease, and conversed familiarly with his friends’; nor, it was said, was he ‘insensible of the charms of beauty, every-where surrounding him.’11

The correspondent did less than justice to the musical proceedings. These included a rendering of Handel’s Jephtha organized by Joseph Cradock who, it was claimed, had gathered for the occasion the greatest number of musicians hitherto assembled in England. The celebrated Giardini led the band, Mr. Commissioner Bates (Lord Sandwich’s secretary), accompanied the choruses at the organ, while the First Lord, who had specially selected the oratorio, took the kettle-drums on both days. The self-styled dilettante, William Gardiner, witnessed the performance at the age of four and more than sixty years later still remembered the ‘grandeur’ of the sound created by the noble drummer and the display he made in flourishing his ruffles and drumsticks. ‘I was riveted to the spot,’ Gardiner recalled, ‘and was so captivated with his Lordship’s performance, that for a time I heard but little else.’ He also recollected ‘a tall black man in a singular dress’; it was ‘the savage, Omai’, ‘brought down on purpose to see what effect this grand crash of musical sounds would have upon him.’ His response was gratifyingly dramatic: ‘He stood up all the time, in wild amazement at what was going on ….’12

Mr. Cradock himself noted that Omai ‘attracted the eyes of the company more than any one’ and supplied a further quota of somewhat banal anecdote. Banks evidently kept his charge under close supervision, for the morning after their arrival, Cradock relates, he was called up by a waiter very early and told that the ‘stranger gentleman’ had run away.

I hastily dressed myself, and endeavoured to pursue him as quick as possible. All windows of the market-place were shut, but one gentleman was just opening his door, to take his early walk, and to him I communicated my distress. ‘You need not be alarmed,’ says he; ‘for such a person as you describe I have just seen from my chamber window, walking about very leisurely, and we can instantly overtake him.’ When we found him, Omai expressed no anxiety or surprise, but returned with us with the utmost good humour and quietude. This was the first time he seemed to have obtained his liberty, and he made the most of it.

‘Omai was not averse from admiration,’ Cradock continued, ‘and he soon gave me to understand how very happy he felt himself to be at Leicester, for he was kindly received every where ….’ He showed marked aptitude for dancing, and a ‘sprightly agreeable lady’ who undertook his instruction said that in a week or two she would have taken the floor with him at an assembly. In the tea-room he was ‘the happiest among the happy, very gallantly handing about cake and bread-and-butter to the ladies’. He was, in short, ‘naturally genteel and prepossessing’, yet not without vanity. He was ‘attentive to dress’ and at one function expressed his anger to Cradock and Mr. Bates because his clothes were not as good as those of the gentleman next to him: his own suit was only of English velvet, while his neighbour’s was ‘from Genoa’.13

Omai was something of a dandy but he was also an immortal soul, the representative of a heathen and illiterate people. If Banks was indifferent to these facts or, amid the frivolities of Leicester, had overlooked them, he was reminded of higher things by a letter received in late September. The writer was one, Richard Stevens, who, addressing Banks and Solander from the post office at Birmingham, explained that he had heard ‘Omiah the Otaheite’ would shortly return to his native country. ‘Would it not’, he urged, ‘be a Laudable Undertaking to send a Person, or Persons along with him to Convert if possible his Countrymen to the Christian Religion, & instruct them in some Branches of usefull knowledge; such as, Reading, Writing, & Accots?’ ‘If such a Plan shou’d be put in Execution,’ he wrote, ‘I make an Offer of myself to go.’ The two gentlemen would perhaps be surprised that a young man (for he was only twenty-eight) should desire to banish himself to so remote a country. The reason, Stevens frankly explained, was that for the past seven years he had experienced nothing but the most severe misfortunes and saw no probability of a change; hence he would go to any part of the world if he could better his lot. ‘I dare say’, he ventured, ‘if Government was to send a Person over, it wou’d be upon an eligible footing.’ His qualifications for this or some alternative post (such as companion to a nobleman or gentleman, he suggested) were the mastery of ‘a fine Hand’, and an understanding of the French language which he was ‘allow’d to speak … with a pure Accent’. ‘My Caracter’, he finally claimed, ‘is irreproachable ….’14

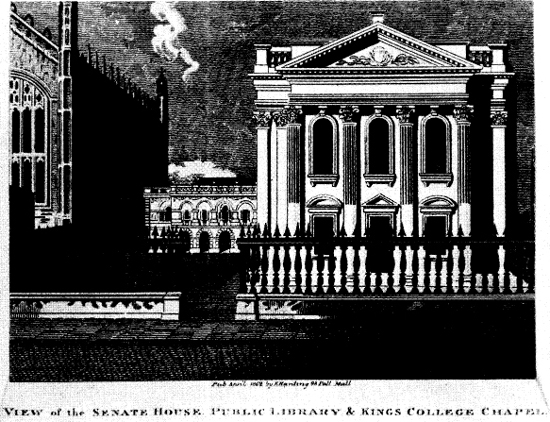

Higher matters were again in the ascendant when Omai paid a long-delayed visit to the University of Cambridge early in October. ‘The Doctors and Professors struck him wonderfully,’ reported a press correspondent, ‘and he would fain have done homage to some, supposing them in a near relation to the Deity.’ Indeed, by ‘his superstitious dread of every thing which he looked upon as sacred’, Omai displayed ‘many marks of natural religion’. ‘In his own country’, the writer observed, ‘he is himself in the Priesthood, which may be an additional reason for his attention to these things, and ought to be a motive with our Divines, to embrace this opportunity of enlightening his mind with the knowledge of true religion, and of sending amongst a nation of idolaters so able a missionary, and so likely to succeed.’ Since coming to England, it was further noted, Omai had learned the use of firearms and was determined, he said, as soon as he returned, ‘to shoot the King of Bolabola, who murdered his father.’ The warrior-cleric was suitably arrayed in military uniform, ‘his hair dressed and tied behind’, and diverted the company with his naïve wit: ‘Some one offered him a pinch of snuff, which he politely refused, saying, that his nose was not hungry.’15

Banks was not named in the press report, but his presence was mentioned by another observer, Richard Cumberland. Writing to his younger brother George on 10 October ‘From My Cell in Maudlin’, this slightly disgruntled candidate for holy orders censured the behaviour of the Cambridge election mob, ‘as happy as the Juice of Malt coud make them’, and described the visit he had paid to the Senate House that afternoon when the results were announced. He thought he had never seen the place so full before and singled out two notabilities for special mention:

Banks & Omiah were present the whole Time & the Latter was introduced to all the Drs &c & behaved with wonderful ease & propriety — He is a stout well made Fellow: in Features & Complection something betwixt the Negro & Indian; was dress’d in a plain Suit with His Hair in the modern Style & seemd to talk & laugh much, tho I was not near enough to hear Him & in short gave great Satisfaction to all about Him — A rep[ly] made to one who offer’d Snuff was very good — No tank You, Sir, My Nose be no Hungry — a severe Satire on Snuff Takers. This is all I have heard or seen of Him.

George Cumberland, who, his brother discloses, was a follower of Rousseau, received the meagre impressions with enthusiasm: ‘you cant conceive how you oblige me by your account of Omiah,’ he wrote from London a week later, ‘every little anecdote of a man born in full health and strength with all the Facultys of understanding (for such Omiah may be said to be, every thing he sees being new,) is well worth remarking; I hope you will be able to get yourself introduced to him before he quits Cambridge’.16

It seems unlikely that the obscure student was able to realize his brother’s aspirations. The Cambridge visit was apparently quite short and towards the end of the month Banks and Omai were back in London. Their movements in the intervening fortnight remain a blank, unrecorded by their regular correspondents and unreported by the newspapers. Miss Banks did from time to time enter her jottings, but they were concerned less with Omai’s current activities than with his past and his future. Her friend Miss Cox, she noted early in October, had heard from a nameless ‘Lady’ visiting Hertford at the time of Omai’s inoculation how ‘monstrously pleased’ she was with the ‘humanity of his Behaviour’; and she mentioned his grief while attending a funeral and his disgust at seeing anglers bait their hooks with live worms (two items Sarah Sophia could have drawn more directly from the newspapers). The next memorandum referred to practical and pecuniary matters. On meeting Dr. Solander, another friend of Miss Banks had asked who was paying Omai’s expenses. The reply was that, while the visitor travelled with her brother, he bore them, except for clothes which the Admiralty furnished; but lodgings had now been taken for the Adventure’s surgeon and Omai who, nevertheless, Dr. Solander ‘imagined’, would be much more with her brother than anyone else, ‘by way of going excursions with him &c.’ The doctor also spoke of the King’s promise to repatriate Omai and his countryman on the Resolution: the intention was not, he said, ‘for the English to make by Force a settlement at Otaheite but by treating the Natives well & sending them home will we suppose make them our Friends in a much more humane & agreable manner.’ Dr. Solander in person, Sarah Sophia recorded on 23 October, told her the Resolution was not expected till ‘the very latter end of next Summer’. Omai, he informed her on the same occasion, was ‘now perfectly contented with staying as he considers the great pleasure he shall have in shewing Every thing he has seen & Explaining to his Countreymen.’17

OMAI’S STAY IN LONDON at the end of October was a brief one. He and Mr. Banks had returned from the country the day before, Solander told Ellis on the 27th, and he would again go down to Hinchingbrooke with Lord Sandwich on the 29th.18 On the uncertain authority of Miss Banks, it may have been during the three nights of this fleeting visit that he was introduced to the English theatre. Sarah Sophia had taken advantage of her brother’s presence to ply him with questions concerning his charge whom she now depicted in the most favourable light. Omai was not only ‘a Priest in his own Countrey’, she was finally convinced, but ‘a well behaved quiet sensible Man desirous strongly of associating with the best Company & behaving in a proper manner.’ In general, she believed, he disliked entering places of religious worship, ‘saying till I understand how to address myself in a proper manner to Your God I dont think it right’. Surely he showed a proper humility, Miss Banks commented, and she wondered whether this was why he had declined to attend prayers on the Adventure, ‘& not from any fear of being eat.’ She spoke of his decorous behaviour at Court (that ‘silly report’ of his fears that the King might eat him was ‘intirely devoid of truth’) and, to illustrate his preference for the best people, went on to describe his visits to the theatre with her brother:

At Sadlers Wells he was much pleased desired he might go the next night wch my Brother complied with & carried him the 2d time he asked if Ld Sandwich ever went? no I believe not: does any of the Nobility go? sometimes but seldom: I will go no more says Omai Very well says my Brother I will carry you tomorrow night to the Play where the Great People frequently amuse themselves.

Accordingly, Banks took him to a more fashionable theatre, with rather disappointing results. While very attentive for the first two acts, Omai was not much diverted and asked if people came there to have conversation; ‘but some scenery towards the end & a Pantomime entertained him very well.’19

With her brother’s help Sarah Sophia amplified topics picked up from other informants and learned of some that were novel. Omai, Banks told her, was ‘not so much delighted at the thought of seeing his Countreyman’ on the Resolution, for he knew ‘the person coming over to be a Bola Bola Man’. From the same authoritative source she confirmed accounts of Omai’s grief on attending a funeral at Hertford; on the other hand, his refusal to eat fish caught with live bait was not entirely because of humane feelings but ‘owing to a Religious Superstition wch prevails in the S. Sea Islands in favour of worms.’ On the important question of finance (so far as her microscopic script can be deciphered), Miss Banks understood that ‘Government’ had authorized her brother to incur whatever expenses he thought proper on Omai’s behalf and to supply him with any pocket money required for use in public places. The authorities, she noted, had also fixed on someone whose name eluded her (in fact Mr. Andrews) ‘to have the care of Omai’ at a salary which would not begin until he returned from Hinchingbrooke where he was when she wrote towards the end of October. In her final entry, on 3 November, Sarah Sophia recorded without rancour a mild affront to her sex and nation: Omai did not like Englishwomen and therefore (contrary to her earlier statement) did ‘not wish for a wife of this Country.’20

29 Omai by Nathanial Dance, 1774

30 Bartolozzi’s engraving of Dance, from a copy once owned by Banh

A week later, while the fastidious visitor was still rusticating with the First Lord (and also, presumably, with that accomplished Englishwoman Miss Martha Ray), his name cropped up in the correspondence of his friends. On the 10th Solander sent Banks a message to say that Bartolozzi had called that morning at New Burlington Street with some of ‘Omais prints’ and had, he believed, sent others with a framed copy to Lord Sandwich. But, Solander went on, he had observed that in the inscription Ulaietea was misspelt Utaietea. Luckily, not above seventy copies had been taken off and, if Banks wanted his own replaced by corrected ones, would he let Solander know? However, he pointed out, ‘I think the error may pass as a proof of their being first Impressions’. He also discussed the absorbing subject of ‘Electrical Eels’ and promised his friend, apparently absent somewhere in the country, that the guns, which Greville expected before the end of the week, would be sent down as soon as they came; and if Banks’s ‘Russian Shoes’ could be found they too would be sent.21

The engraving to which Solander referred was based on a small portrait by Nathaniel Dance probably commissioned by Banks. If less attractive than the pastels of the Eskimo family done by the same artist in the previous year, the pencil drawing seems to be a faithful likeness, wholly exempt from the charge of flattery levelled at the earlier head by Hodges. Omai is shown in voluminous robes of Tahitian cloth, a plaited bag and feather chaplet in the right hand, the left arm clasping a wooden stool. The hands are tattooed, the feet bare, and the shoulder-length hair falls in loose ringlets. The nose is certainly ‘flatish’ (but not exceptionally so for a Polynesian), the gaze steady, the expression impassive, with perhaps a hint of that ‘sulkiness’ to which the subject was occasionally liable. Bartolozzi in his turn had reproduced the drawing with the utmost fidelity — or at least the details of dress and accessories. With the head he was less successful: the face is thinner and longer than in the original drawing, the expression more animated, the hair more abundant, the nose even more negroid; altogether, his Omai, despite the nose, conjures up the Mediterranean rather than the Pacific.

Bartolozzi’s engraving reached the print shops at a time when the subject of Tahiti was again entertaining fashionable readers. Silent since the publication of the ‘Epistle from Harriot’ earlier in the year, the witlings had lately renewed their satirical attacks in two works exploiting similar mildly salacious themes and following the same mock-heroic, mock-scholastic conventions. An Epistle (Moral and Philosophical) from an Officer at Otaheite, attributed to the politician John Courtenay, was addressed to a notorious divorcée, transparently veiled as Lady Gr*s**n*r. Apart from references in the opening invocation to ‘circling arms’, ‘elastic hips’, and ‘ermin’d sages’, little was said of the Grosvenor trial which had diverted society in 1772. The chief topics were those staples of Tahitian satire — sexual promiscuity, public copulation, infanticide, the tattooing of buttocks, the introduction of venereal disease — supported by quotations from Hawkesworth or the classics or, on one occasion, by a private letter from Dr. Solander. But Courtenay could discard his jocular and cynical manner to write with passion of ‘lewd Kath’rine’, comparing Russia and its ‘dire Virago’ with those ‘southern isles’ where ‘Oberea’s gentle virtues’ prevailed. He celebrated the islanders’ ‘innocence’ and, again drawing on Hawkesworth, praised their courage in the face of Wallis’s attack:

In their canoes, our floating forts defy,

Nor from the thunder of our cannon fly.

Admiration, fear, and prayer were combined in the lines that followed:

Beauty and Valour here have fix’d their throne,

— Shall Europe’s spoilers call this isle their own?

May Heav’n and Britain shield the gen’rous race,

Nor Tyranny their manly souls debase.22

The other work was more directly related to previous satires on Banks and the dead Hawkesworth; its authorship, indeed, is sometimes credited to Scott, the putative begetter of the Oberea cycle. With a sensitive nose for the topical, the versifier now brought Omai into the sequence, introducing him on the title-page as ‘his Excellency Otaipairoo, Envoy Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary from the Queen of Otaheite, To the Court of Great Britain and bearer of A Second Letter from Oberea … to Joseph Banks, Esq. His Excellency’s unexpected arrival from ‘so voluptuous a Court as that of Otaheite’ had revived the spirits of ‘every member of the fashionable societies in the neighbourhood of St. James’s’, ran an introduction which proceeded to give authentic particulars of ‘this celebrated foreigner’. The particulars prove on examination to have been culled from newspaper articles, sometimes slightly altered or amplified. Befitting his new dignity, Omai-Otaipairoo had moved up a couple of rungs on the social ladder from ‘mobility’ to ‘nobility’. At the Cape of Good Hope he was said to have been ‘exceedingly pleased’ with a Dutch lady, parted from her ‘with some reluctance’, and when returning on board ‘ran back a considerable distance to salute her.’ On the other hand, at the English Court he did not seem to take ‘any extraordinary notice of the ladies’; ‘probably’, the author moralized, ‘the outre of their dress disgusted him as it really does every admirer of simple nature.’ However, it was ‘a positive fact’ that ‘a lady on the first line of nobility’ (presumably the Duchess of Gloucester) had ‘conceived a particular penchant for this spirited adventurer’ who would ‘spend a few weeks at her grace’s villa.’23

31 A further addition to the Oberea cycle

Except for his prominent part in the introduction and his designation as queen’s courier on the title-page, Omai has no place in the satire itself which reiterates the familiar themes of the series in monotonously familiar measures. The bereft Oberea reproaches her absent Banks-Opano for his desertion while proclaiming her continued loyalty to

A Love as true

As any Maid in any clime e’er knew.

Haply tho’ now some fairer She you press,

You know not any more expert to bless.

Repetitiously and with a profusion of suggestive detail, she recalls the beginning of their liaison, its progress, and its consummation until she reaches the climax of her lament and introduces the one element of novelty — the announcement that after ‘nine moons had gone their nightly round’, the fruits of her union with Opano made their appearance:

Two young Opanos grace the royal bed:

Vig’rous the boys, and ah! so like the sire,

They prove how warm, how pure was my desire ….

As the satire draws to a close, the twin princes unite their tears and lisping reproaches with Oberea’s:

E’en now, methinks, while dandling on my knee,

In words half-form’d they strive to talk of thee;

And, when they weep, I almost hear them say

Why, cruel, went our Father far away;

Why, curious, he, new herbs and roots to gain,

Thus left us far amidst the Southern main ….24

BANKS’S RESPONSE to this and previous lampoons must remain a matter for conjecture. On the slight evidence of the letter Solander sent to him early in November he may have sought refuge from the knowing looks and malicious titters of London society on his Lincolnshire estate or elsewhere in the country; possibly his flight was so precipitate that he left behind indispensable fowling-pieces and cherished footwear. Whatever the facts, towards the end of the month he was back in town, again confronting the fashionable world and escorting Omai, who had returned from Hinchingbrooke, through a succession of social engagements. In one crowded week the young islander again visited the theatre, attended the House of Lords for the opening of parliament, heard the King deplore ‘a most daring spirit of resistance’ in the colony of Massachusetts, dined at least once with members of the Royal Society, and, most memorably, called on Dr. Burney and his family.25

The Burneys had recently established themselves in an historic house, once the home of Sir Isaac Newton, in St. Martin’s Street, Leicester Square. Fanny found the street ‘odious’ after spacious Queen Square, but it was in the centre of the town and the locality was not lacking in congenial and accomplished neighbours. The studio of Sir Joshua Reynolds stood scarcely twenty yards away, while Mr. Strange, the well-known engraver, also lived near Newton House. There on the last day of November Dr. Burney entertained ‘this lyon of lyons’, as Fanny now termed Omai in her diary, or ‘this great personage’, the phrase used in an immensely long letter she sent the next day to her old friend Samuel Crisp at Chessington Hall in Surrey.26

The function, Fanny informed Mr. Crisp, was the outcome of a chance meeting of her brother Jem’s at a performance of the play Isabella at Drury Lane. Spying Mr. Banks and Omai from his upper box, he approached them to talk. Omai welcomed his shipboard friend ‘with a hearty Shake of the Hand’ and made room for him by his side. Jem then invited both men to dine at his father’s, but Mr. Banks was unable to accept: ‘he believed he was engaged every Day till the holy days, which he was to spend at Hinchinbrooke.’ Very late the following night Jem received this note (presumably in the hand of an amanuensis):

Omai presents his Compts to Mr Burney. & if it is agreeable & Convenient to him, he will do himself the Honour of Dining with Mr Burney to morrow, but if it is not so, omai will wait upon Mr Burney some other Time that shall suit him better. omai begs to have an answer, & that if he is to come, begs Mr Burney will fetch him.

The next morning Jem waited on Mr. Banks with Dr. Burney’s compliments and a further plea for his company and Dr. Solander’s; but ‘they were Engaged at the Royal Society.’ In the end they did call briefly at St. Martin’s Street, bringing Omai at two o’clock after they had taken him to the House of Lords to hear the King make his speech from the throne. Except for Mr. Strange and another old friend, Mr. Hayes, who had come ‘at their own Motion’, it was a family party made up of Dr. and Mrs. Burney, the three unmarried sisters, Fanny, Susan, and Charlotte, with Jem and Dick, the last a child of six years. Fanny had been confined to her room with a cold for several days and delayed her appearance until the two escorts left when she came down ‘very much wrapt up, & quite a figure’.27

On entering the room, she found the guest ‘Seated on the Great Chair’ next to her brother who was ‘talking otaheite as fast as possible’; ‘You cannot suppose how fluently & easily Jem speaks it’, she wrote. Omai himself was in court dress and ‘very fine’: he wore ‘a suit of Manchester velvet, lined with white satten, a Bag, lace Ruffles’, and a sword which the King had given him. He was tall and very well made, much darker than Fanny had expected, ‘by no means handsome’, but with a ‘pleasing Countenance’. His hands were ‘very much tattowed’, but his face not at all. As Jem introduced them, Omai rose, made a ‘very fine Bow’, and then seated himself again. ‘But’, Fanny related,

when Jem went on, & told him that I was not well, he again directly rose, & muttering something of the Fire, in a very polite manner, without Speech insisted upon my taking his Seat, — & he would not be refused. He then drew his Chair next to mine, & looking at me with an expression of pity, Said, ‘very well to-morrow-morrow?’ — I imagine he meant I hope you will be very well in two or 3 morrows — & when I shook my Head, he said ‘no? O very bad!’

‘He makes remarkably good Bows’, she added, ‘— not for him, but for any body, however long under a Dancing Master’s care. Indeed he seems to Shame Education, for his manners are so extremely graceful, & he is so polite, attentive, & easy, that you would have thought he came from some foreign Court.’28

32 Fanny Burney, after E. F. Burney

Omai continued to display the same courtly refinement in the course of the dinner. The moment he was served, he presented the plate to Fanny, who sat beside him, and on her declining it, had not, she explained, ‘the over shot politeness to offer all around, as I have seen some people do, but took it quietly Again.’ ‘He Eat heartily’, she went on, ‘& committed not the slightest blunder at Table, neither did he do any thing awkwardly or ungainly.’ She particularly noted one instance of his courtesy which went beyond any mere question of formal manners: ‘He found by the turn of the Conversation, & some wry faces, that a Joint of Beef was not roasted enough, & therefore when he was helped, he took great pains to assure mama that he liked it, & said two or three Times “very dood —, very dood.”’ ‘It is very odd, but true,’ she commented, ‘that he can pronounce the th, as in Thank you, & the w, as in well, & yet cannot say G, which he used a d for. But I now recollect, that in the beginning of a word, as George, he can pronounce it.’ Sometimes, she observed, he communicated silently: when being introduced to Mr. Strange and Mr. Hayes, for instance, he paid his compliments ‘with great politeness’ but ‘without words’.29

As the meal progressed, Fanny was again struck by the guest’s untaught command of manners, this time in dealing with a servant. He was given porter instead of the small beer he had asked for, but was too well bred to send it back and when the beer was brought also, he merely laughed, exclaiming ‘Two!’ During this contretemps one glass hit against the other which ‘occasiond a little sprinkling’ and prompted Fanny to further admiring comment: ‘He was shocked extremely — indeed I was afraid for his fine Cloaths, & would have pin’d up the wet Table Cloth, to prevent its hurting them — but he would not permit me; &, by his manner seemed to intreat me not to trouble myself! — however, he had thought enough to spread his Napkin wider over his Knee.’ When Mr. Hayes inquired, through Jem, how he liked the King and his speech, he ‘had the politeness to try to answer in English, & to Mr Hayes — & said “very well, King George!”’ Dinner ended with a toast to the King, proposed by Mrs. Burney, whereupon Omai ‘made a Bow, & said “Thank you, madam,” & then tost off “King George!”’30

They dined at four and after the meal Omai informed Jem that at six o’clock he was to go with Dr. Solander ‘to see no less than 12 Ladies’. Jem in turn translated the speech to the rest of the company, watched by Omai who understood he was being talked about and, laughing heartily, ‘began to Count, with his Fingers, in order to be understood — “1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. — twelve — woman!”’ Before six o’clock he was informed of the arrival of his coach with the announcement, ‘Mr omai’s Servant.’ He answered, ‘Very well!’ but remained seated for about five minutes before rising to get his hat and sword. As Dr. Burney was speaking to Mr. Strange, Omai stood aside, ‘neither chusing to interrupt him, nor to make his Compliments to any body else first. When he was disengaged, Omai went up to him, & made an exceeding fine Bow, — the same to mama — then seperately to every one in the Company, & then went out with Jem to his Coach.’31

When summing up her impressions Fanny was abject in her praise. Omai was not merely ‘a perfectly rational & intelligent man’ but in understanding was, she claimed, ‘far superior to the common race of us cultivated gentry’; otherwise he could not have ‘borne so well the way of Life’ into which he had been thrown. ‘I assure you every body was delighted with him’, she informed Mr. Crisp. Her regret was that she could not speak his language — unlike Lord Sandwich who had ‘actually’ studied it ‘so as to make himself understood’. The bookish Burneys did, however, extract a timely moral from the recently published Letters of Lord Chesterfield to his son. Ever since the dinner, Fanny went on, their conversation had turned upon

Mr Stanhope & omai — the lst with all the advantage of Lord Chesterfield’s Instructions, brought up at a great School, Introduced at 15 to a Court, taught all possible accomplishments from an Infant, & having all the care, expence, labour & benefit of the best Education that any man can receive, — proved after it all a meer pedantic Booby: — the 2nd with no Tutor but Nature, changes after he is grown up, his Dress, his way of Life, his Diet, his Country & his friends; — & appears in a new world like a man [who] had all his life studied the Graces, & attended with un[re]mitting application & diligence to form his manners, & to render his appearance & behaviour politely easy, & thoroughly well bredl I think this shews how much Nature can do without art, than art with all her refinement, unassisted by Nature.

If she had been ‘too prolix’, Fanny told Mr. Crisp, she must be excused, for the fault was wholly owing to the ‘great curiosity’ she had heard him express for whatever concerned Omai. Her father, she promised, would arrange a meeting when the visitor from the South Seas returned to town after spending the holidays with Lord Sandwich.32

Before leaving for Hinchingbrooke Omai came under the calmer scrutiny of another observer, the Revd. Sir John Cullum, who met the ‘Native of Ulaietea’ on two occasions, once at a Royal Society dinner and again at Mr. Banks’s house. The baronet (antiquarian, botanist, and country parson) laboured over the record of his impressions and finally asked his friend, the Revd. Michael Tyson, Fellow of Bene’t College, Cambridge, whether he would care to read the result. Mr. Tyson, a man of similar interests, was glad to accept the offer, mentioning in his reply that he, too, had seen Omai when he visited the university and was ‘much pleased with his appearance — there was an openess of countenance, and a native politeness that would do honour to any Englishman.’ In his next letter Sir John accordingly included ‘the Account of Omai’ (‘such as it is’, he diffidently remarked), which he dated 3 December 1774.33

Cullum estimated the islander’s age at ‘about 30’, described him as ‘rather tall and slender’, with an erect carriage, and thought his face ‘on the whole … not disagreeable’. In more precise terms he listed the salient features of this new specimen of the human race — the ‘some-what flat’ nose, the thick lips, the ears ‘bored with a large Hole at the Tip’, the swarthy complexion, the hair ‘of a considerable Length, and perfectly black’, the tattoo marks on hands and posteriors, not in continuous lines, it was noted, but in rows of ‘distinct bluish Spots’ — and went on the pay the now customary tributes to the ‘tolerably genteel Bow, and other Expressions of Civility’ he had acquired since arriving. The man appeared to have ‘good natural Parts’, had learned a little English, and was ‘in general desirous of Improvement’; in particular he wished to learn to write which, he said, ‘would on his Return enable him to be of the greatest Benefit to his Country’; ‘but’, commented Sir John, ‘I do not find, that any Steps have been taken towards giving him any useful Knowledge, Mr Banks seeming to keep him, as an Object of Curiosity, to observe the Workings of an untutored, unenlightened Mind.’34

33 Silhouette of Omai

As an amateur of science himself, Cullum followed with interest the actions of this unschooled man of nature and recorded various ‘Notices’, based on direct observation or inquiry. In a serious mood or while following what others were saying, Omai’s ‘Look’ was ‘sharp and sensible’, but his laugh was ‘rather childish’. If he wanted you to understand something he had seen, he used ‘very lively and significant Gestures’ — he was in truth ‘a most excellent Pantomime’. He was pleased with trifling amusements (‘as many of more improved Understandings often are’, added the fair-minded Cullum) and was unhappy when he had nothing to entertain him. Here followed one of the scrupulous writer’s recent impressions:

when I dined with him, with the Royal Society, a small multiplying Glass had been newly put into his Hands: he was perpetually pulling it out of his Pocket, and looking at the Candles &c with excessive Delight and Admiration: we all laughed at his Simplicity; and yet probably the wisest Person present would have wondered as much, if that Knick-Knack had then for the first Time been presented to him.

A further anecdote seems to refer back to Omai’s Antarctic voyaging and perhaps indicates the onset of his first English winter. He had, wrote Cullum, seen hail before his arrival and was therefore not much surprised at a fall of snow which he called, naturally enough, ‘white Rain’. But he was ‘prodigiously struck’ on seeing and handling a piece of ice; ‘and when he was told, that it was sometimes thick and strong enough to bear Men, and other great Weights, he could scarcely be made to believe it.’35

Omai, on Cullum’s authority, was entirely reconciled to European manners and customs, conformed to the English diet which he liked very well, denied (‘against Self-Conviction’) that his countrymen ate human flesh, and drank wine but was ‘not at all greedy of it’ — he had never been intoxicated since he arrived. In direct contradiction of Miss Banks’s latest findings, he was said to like Englishwomen, ‘particularly those of a ruddy Complexion, that are not fat.’ He submitted ‘most readily to the slightest Controul’ without ‘the least Appearance of a fierce and savage Temper’; Cullum had seen him, in the company of a gentleman who encouraged him, display ‘all the cheerful and unsuspecting Good-Nature of Childhood’. The print recently engraved by Bartolozzi from Dance’s drawing Sir John considered ‘fine’ in execution and ‘extremely like’ the subject.36

Tyson was grateful for his friend’s impressions and hastened to add his own small quota. ‘I thank you much’, he wrote, ‘for your admirable account of Omai, wch greatly entertained me’. He had seen the man at Cambridge, he repeated, and listened to a conversation between him and Banks. ‘I have heard much of him’, he went on, ‘from people who have been long and frequently in his company — particularly the BP of Lincoln — who said that he observ’d the two leading principles of his Mind were, a regard for Religion, and desire for revenge’. Tyson was evidently of the same opinion. He knew several academics, he said, to whom Omai paid special regard on finding out they were priests; and he was most offended when the Bishop of Lincoln sat at table between two ladies — ‘a custom not allow’d the high-Priests in his country’. As for revenge, ‘his desire to shoot his enemy the King of Bolabola is always uppermost, when his thoughts are not employ’d about novelties.’ Tyson considered it would be impossible to teach him to form words and even more so to convey the art to his countrymen, though he might learn to make letters. And was Cullum not mistaken in suggesting that Omai’s people ate human flesh? Surely the practice was confined to the New Zealanders.37

Meanwhile the subject of this solemn discourse was pursuing his heedless way in English society. After his glimpse of the London season, Omai set off to spend the holidays with Lord Sandwich. But in spite of what he had told James Burney, Banks did not join the Christmas gathering at Hinchingbrooke; nor did he attend the Handel festival held there to celebrate the New Year. At that time he seems to have been much occupied with his scientific pursuits. Late in November he had again been elected to the Council of the Royal Society — along with Solander and Constantine Phipps — and may have been engaged in discussions on the new voyage of discovery that was to leave for the Pacific after the Resolution’s return. More certainly he was fully employed in setting up at New Burlington Street a collection he had acquired from the estate of Philip Miller, for many years curator of the Apothecaries’ Garden at Chelsea. ‘Mr. Banks has bought Miller’s Herbarium,’ Solander informed John Ellis on 21 December, ‘and we have been busy these two weeks in getting it home and into some order.’38 His failure to pay the promised visit provoked somewhat excessive emotion among friends and admirers at Hinchingbrooke. ‘We are all’, wrote Sandwich on the 29th, ‘extremely disappointed & unhappy at not having had the pleasure of seeing you according to the hopes you had given us ….’ Having decided he had no chance of winning, the sporting earl went on, he had ‘with great concern’ paid a bet of five shillings for Banks’s failure to appear at breakfast that morning.39

Sandwich had other reasons for concern. In the same letter he explained:

Omai is the bearer of this — I own I am grown so used to him, and have so sincere a friendship for him, from his very good temper, sense, & general good behaviour, that I am quite distressed at his leaving me; &, knowing the dangers of a London life to an European of twenty one years old, am full of anxiety on account of the winter he is to pass in town in a Lodging, without the sort of society he has been used to, which has kept him out of dissipation.

He knew that Banks had the same feelings about their friend as he did, the conscientious First Lord continued, and hoped that when they met they would be able to discuss how they could manage Omai’s situation to the best advantage. The visitor’s safety, he summed it up, ‘must depend upon you & me; & I should think we were highly blameable if we did not make use of all the sagacity & knowledge of the world which our experience has given us, to do every thing we can to prove ourselves his real friends’. Finally, he subscribed himself ‘with great truth & regard’ Banks’s ‘most obedient & most faithful servant Sandwich’.40

HIS LORDSHIP’S LETTER marked the climax of Omai’s début in English society. Since his arrival in July this average Polynesian, casually enlisted and carried across the world by chance, had become a celebrity, the protégé of royal personages and aristocrats, the associate of scientists and savants, the focus of attention in public assemblies and polite drawing-rooms. How had this astonishing transformation come to pass in the space of a few short months? One answer to a complex question is at least clear: the way had been thoroughly prepared for the voyager before he disembarked. He had benefited from popular interest in the South Seas during recent years and from the work of numerous writers in periodicals, books, and newspapers. By the early seventeen-seventies Otaheite and the Society Islands had become familiar terms to most educated Englishmen. Hence it was not surprising that students of Bougainville should seek out the native from New Cythera or that readers of Hawkesworth should court the company of Oberea’s supposed countryman. Their motives in so doing were inevitably mixed. To many Omai was merely the reigning lion; to some observers of scientific bent he was a specimen to be described and classified; to a few he was the embodiment of an idea, the personification of ‘natural man’; to others — exemplified by Miss Burney and Sir John Cullum — he was a combination of all three.

Omai was also an individual and much of his success, it must be acknowledged, was due to qualities that were either peculiar to himself or derived from his antecedents and upbringing. With monotonous unanimity witnesses testified to his cheerfulness, his politeness, his obedience. He seems to have been amiable and tractable by nature, but in addition he was a representative of his class and his people. Society Islanders (with the possible exception of the Boraborans) were already noted for their friendliness and, unlike the Tahitians in this respect, European navigators had not found it necessary to batter them into civility. Moreover, as a member of the raatira (and incidentally as an exile), Omai had been deferring to his superiors since childhood. There was no novelty for him in a population ranging from the lowly and despised to the high-born and privileged; nor did he find it at all unusual to demonstrate his esteem by means of prescribed rites and formulas. After all, as some newspaper commentators perceived, he was not a naked ‘savage’ but the product of a settled and relatively sophisticated manner of life. He soon adapted himself to English society because in its hierarchical structure and its formality it resembled his own. Nor were all its customs and institutions wholly unfamiliar. It was obvious, for example, that a pantomime at Drury Lane was only an elaborate performance by the local arioi. As for the strange ritual of inoculation, was it not just a mild European equivalent to the ordeal of tattooing or the ceremony of supercision?

So this unexceptional denizen of the South Seas had taken his place in the new environment with comparative ease. It seems unlikely, however, that he would have scaled the heights, or even reached the foothills, had he not been aided by influential patrons. To the combined efforts of Banks and Sandwich he owed his introduction to Court and aristocracy, his tour of the provinces, his several meetings with members of the Royal Society, and his triumphs at Hinchingbrooke and during the London season. Now, towards the close of December, he was back in town and, as Banks again took over responsibility for the young man’s well-being, he could reckon up the consequences of his own benevolent efforts in the past few months. While on the debit side his botanizing had suffered and the ‘grand Natural History Work’ still languished, the gains were considerable. Five years before, on the point of leaving Tahiti, he had announced his decision to carry off a substitute for his neighbours’ captive lions and tigers. After the disappointment of Tupia’s death, he had at length achieved his ambition. Probably, indeed, Omai filled the role of human curiosity far better than the ‘proud and obstinate’ Tupia would ever have done. Through the docile visitor’s presence Banks had done much to assuage his nostalgia for the South Seas, he had consoled himself in some measure for the abandoned voyage, and he had restored or even enhanced his public reputation. Above all, he had mended the breach with his old friend Sandwich. From that reconciliation what inestimable benefits might not flow in the future? In accordance with His Majesty’s wishes, Omai must be restored to his native sphere; a new expedition would be equipped and manned; doubtless, as in the past, naturalists would be included among the supernumeraries. Like Solander in his letter to Lind, Banks would hardly have dared to contemplate the exciting prospects before him.

For the present there were more urgent matters to consider — Omai’s accommodation, his physical needs and desires, his moral welfare. And when the year 1774 at last came to an end, debts and credits in the most literal sense must be reckoned up. Among the Banks papers there survive a number of documents listing expenses incurred during the visitor’s stay in England. As disclosed by the first of the series, his personal allowance in the previous six months had not been excessive. He had received two advances, both of five guineas, one a week after his arrival, the other on 27 August, the day he left London for the first house party at Hinchingbrooke. The episode at Hertford accounted for a couple of items: 15/6 for the servants of the inoculation house, twenty guineas for Baron Dimsdale, the fee already approved by Lord Sandwich. Banks’s housekeeper, Mrs. Hawley, was paid £8-3-3 and one of his servants, Alex Scott, £4-7-6, both for unspecified services. The remaining sums, ranging from 7/- to £8-12-6, probably represented transactions with tradesmen and firms, of whom only one can be identified: the hosiers Hunt and Cunningham supplied goods to the value of £11-5-0. Expenditure totalled £116-4-11, but one credit was scrupulously entered — £10-15-6, being ‘Mr Omai’s Wages for the Adventure Sloop’. Altogether he had cost his patrons or ‘Government’ (to follow Miss Banks) £105-9-5, a modest outlay in return for the vast entertainment he had provided.41

35 An early-nineteenth-century glimpse of Warwick Street