WITH HIS ARRIVAL IN LONDON AT THE END OF 1774, THERE OPENED A NEW and less eventful phase of Omai’s stay in England. He was no longer the guest of his two chief patrons, accommodated in their houses, exhibited to their friends, and cosseted by their servants. Following the plan first discussed in the middle of August, he entered lodgings kept by a Mr. De Vignolles or de Vignoles or Vigniol (versions differ) and apparently situated in Warwick Street which was no great distance from New Burlington Street. His conduct could thus be readily supervised by Banks and, as a further precaution against the dangers of metropolitan life, he was placed in the care of Mr. Andrews, formerly surgeon on the Adventure and his companion at Hertford.1 Under this regime his public activities seem to have been curtailed or perhaps he merely chose to remain at Warwick Street without exposing himself to the full rigours of his first northern winter. Whatever the reasons, in the opening weeks of the new year his name was not mentioned in the popular press; nor did it figure either in the correspondence of Banks and his friends or in his sister’s now infrequent jottings. Was it possible, then, that not only the fickle London public but also his appointed guardians had lost interest in the prodigy from the South Seas? The answer must be a qualified negative, but Omai had clearly passed the peak of his current fame.

At the beginning of 1775, it is equally clear, both the newspapers and members of the Banks circle were preoccupied with more serious matters than the doings of a visibly fading celebrity. Grave news continued to reach England from the American colonies, and late in January it was reported that the aged Earl of Chatham had urged in a packed House of Lords the withdrawal of all British troops stationed in Boston.2 Of more immediate concern to Banks and his friends (including Omai) were recent discussions on a further voyage of exploration. Early in the previous year the Royal Society had proposed to the Admiralty the dispatch of a ship or ships to sail up the north-western coast of America ‘so as to discover whether there is a passage into the European Seas.’ After consultations between officials on both sides, the First Lord expressed his interest in the expedition but, for financial and political reasons, decided that it could not be sent until Captain Cook’s return in 1775. As that event grew nearer, plans for the new undertaking were actively canvassed by leading scientists, among them it is reasonable to assume, Banks and his two friends on the Royal Society’s Council. Another, with greater certainty, was the Astronomer Royal, Dr. Maskelyne, who approached James Lind of Edinburgh to see whether he would be willing to go.3

For the second time Dr. Lind was delighted to accept an offer of distant travel and scientific employment — but only on one condition. ‘Nothing’, he wrote on 30 January, ‘will give me more pleasure than to have the honour of going on the intended Voyage you mentioned, for the making discoveries on the N.W. side of America beyond California, provided my friend, Mr Banks, goes’. He wished to assure the Astronomer Royal, however, that he would not go to oblige the Government after their ungenerous treatment of him in return for the sums he had laid out to equip himself for the last abortive venture to the Pacific. ‘But’, he went on, ‘to serve and attend on Mr Banks on whatever Expedition he shall undertake, I shall esteem my Duty, as well as my greatest pleasure, for the real regard I have for so noble and excellent a man.’4

A fortnight later, on 13 February, that paragon of human kind celebrated his thirty-second birthday, an occasion the devoted Sarah Sophia marked by composing a prayer for his continued welfare and reviewing his travels. These, she noted, covered a period of seven years, from the time he left for Newfoundland in 1766 until he returned from Holland in 1773.5 Should his Scottish friend’s hopes be fulfilled, a fresh cycle would soon open. On 2 March Lind wrote to Banks, mentioning the proposals outlined by Maskelyne and emphasizing his own continued loyalty. ‘If such a Voyage takes place, and you go,’ he assured Banks, ‘I shall think myself happy to be permitted to attend you: nor shall I require any inducement from Government for doing what I shall ever esteem my greatest pleasure.’6 There matters were necessarily left to rest until, with the Resolution’s return, arrangements for the latest enterprise would be settled.

These affairs of the great outside world were also of moment to the household in St. Martin’s Street. Entering her diary early in the new year, Fanny Burney remarked that her brother had left them some time before; he had been posted to H.M.S. Cerberus which was ordered to America. She was not at all pleased with the move, though she thanked heaven there was no prospect of a naval engagement, the vessel’s business being only to convey army generals to Boston. In March, while the ‘very honest Tar’ was still at Portsmouth, his name cropped up one afternoon during a call Fanny paid at the Stranges’ where she found Mr. Bruce drinking tea with the ladies. ‘His Abyssinian Majesty’, as Mrs. Strange called her fellow Scot and distant kinsman, first mentioned James, after which, Fanny relates, the conversation turned to Omai and other southern celebrities with whose names and reputations Mr. Bruce had evidently made himself au fait since his arrival from Africa a year before:

When he found my brother was the person in question, and that he was going to America, he said he was sorry for it, as there was going to be another South-Sea Expedition, which would have been much more desirable for him. ‘And,’ said I, ‘much more agreeable to him; for he wishes it of all things. He says he should now make a much better figure at Otaheite, than when there before, as he learnt the language of Omai in his passage home.’

‘Ah, weel, honest lad,’ said Mrs. Strange, ‘I suppose he would get a wife or something pretty there.’

‘Perhaps, Oberea,’ added Mr. Bruce.

‘Poor Oberea,’ said I, ‘he says is dethroned.’

‘But,’ said he archly, ‘if Mr. Banks goes, he will reinstate her! But this poor fellow, Omai, has lost all his time; they have taught him nothing; he will only pass for a consummate liar when he returns; for how can he make them believe half the things he will tell them? He can give them no idea of our houses, carriages, or any thing that will appear probable.’

‘Troth, then,’ cried Mrs. Strange, ‘they should give him a set of dolls’ things and a baby’s house, to show them; he should have every thing in miniature, by way of model; dressed babies, cradles, lying-in-women, and a’ sort of pratty things.’

There was a humorous ingenuity about the suggestion, Fanny observed, and she really believed it would be well worth a trial.7

For some reason, perhaps connected with his son’s posting to the Cerberus, Dr. Burney failed to arrange the promised meeting between Mr. Crisp and Omai, but both he and Jem were topics of discussion in the affectionate letters that passed between Newton House and Chessington Hall. She had no certain news of her brother’s whereabouts, Fanny informed her old friend early in April, but she fancied he was still at Portsmouth. ‘There is’, she continued, ‘much talk of [an in]tended South Sea Expedition: Now You must [know] there is nothing that Jem so earnestly desires as to be of the Party, & my Father has made great Interest at the Admiralty to procure him that pleasure: & as it is not to be undertaken till Capt. Cooke’s return, it is just possible that Jem may be returned himself in Time from America.’ She said nothing of the proposal to search for a passage through Arctic waters to Europe. This expedition, she explained, was to be the last: they were to carry Omai back and give him ‘a Month for liking’; after which, if he did not again ‘relish’ his old home or found himself ill-treated, he was to have it in his power to leave again for England. Later in the month she was able to tell Mr. Crisp that the Cerberus had now sailed, bearing in addition to the ship’s company three generals with their aides and entourage. ‘Their stay is quite uncertain’, she remarked. ‘Jem prays for his return in Time to go to the South Seas.’8

Fanny and her friends might speak airily of Omai’s future, but what of his present condition? And what if he should meet the sad fate of his solitary predecessor? Such were the questions raised at this time by two contributors to the Gentleman’s Magazine. The first, who signed himself H.D., having read ‘the entertaining narrative of the discoveries made by Mr. Banks and Capt. Cook’, expressed the pain he felt at learning his countrymen had acted in a manner supposedly peculiar to the Spanish: ‘I am shockt when I read, that these boasted discoveries, in three years of the 18th century, made by men, by Britons, and by protestants, cost the lives of many Indians.’ With detailed citations, he gave instances of unprovoked shooting and went on to remark:

I might add to all the cruelties of discovery that of transporting a simple barbarian to a christian and civilized country, to debase him into a spectacle and a maccaroni, and to invigorate the seeds of corrupted nature by a course of improved debauchery, and then to send him back, if he survives the contagion of English vices, to revenge himself on his enemies, and die ….

The second writer, quoting from ‘a late voyage’ by an unnamed ‘French officer’ (clearly Bernadin de Saint-Pierre), gave some particulars of Aoutourou before and after his visit to France. While passing through Mauritius with Bougainville, he was ‘free, gay, and rather inclined to libertinism’; when he returned to the island on his way home, he was ‘reserved, polite, and well-bred’. He was ‘enchanted’ with the Parisian opera and mimicked its songs and dances; he owned a watch from which he could tell the hours for rising, eating, etc.; though ‘very intelligent’, he knew little French and expressed his wishes by signs; he seemed ‘much tired’ at Mauritius and always walked out by himself. This poor islander, commented the writer in his own person, never reached home, for he died of smallpox just as he embarked for Tahiti. ‘May a better fate attend Omiah, now in England!’ he exclaimed. ‘Hitherto our world has been “a country from whose bourn/No Taiti-man returns.”’9

WHILE HIS FUTURE WAS THUS DEBATED, Omai had appeared in public, not noticeably debased or debauched but suffering from the rigours of the northern climate. When speaking with him on 24 March, the young German scientist and man of letters, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, asked how the winter in England suited him; to which he replied, ‘cold, cold’, and shook his head. ‘Wishing to express that in his native land only light shirts (if any at all) were worn,’ his interlocutor went on, ‘he indicated this by taking hold of the frill of his shirt and pulling back his vest.’ The meeting took place during a function at the British Museum when Lichtenberg was introduced to Dr. Solander and then to ‘the man from Ulietea’ who offered his hand and shook the visitor’s ‘in the English style’. Lichtenberg, who was not wholly free from racial preconceptions, described Omai as ‘large and well-proportioned’, his skin ‘yellowishbrown’, his face lacking ‘the unpleasantness and protuberance of the negro’s’. Moreover, he ‘had in his demeanour something very pleasant and unassuming which becomes him well and which is beyond the range of expression of any African countenance.’10

Lichtenberg found Omai’s English ‘far from intelligible’ and, had it not been for the help of Mr. Planta, one of the Museum’s librarians, doubted whether he would have understood as much as he did. When asked if he liked England better than his native land, the islander assented; ‘but he could not say yes, instead it sounded almost like vis.’ Yet, oddly enough, he pronounced the English th quite well. His hands, the observer noted, were marked with blue stains which ran in rings round the fingers. Pointing to the right, Omai (lending some colour to Apyrexia’s earlier assertion) ‘said wives, then of the left hand he said friends.’ ‘That’, remarked Lichtenberg, ‘was all that I had the opportunity of saying to him that day; the company was very numerous, and we were both rather shy.’ The young scientist ended his journal entry for 24 March on a reflective note: ‘I found it not unpleasant to see my right hand in the grasp of another hand coming from precisely the opposite end of the earth.’11

For all his shyness, Lichtenberg was a persistent celebrity seeker (earlier in the month he had hunted out Boswell’s hero, General Paoli), and again called on Solander and Omai the next day, this time apparently at New Burlington Street. Mr. Banks had gone hunting, but the visitor had luncheon with other guests, sitting next to Omai who was ‘very lively’. No sooner had he greeted the company than ‘he sat down before the tea-table and made the tea with all decorum.’ He ate nothing baked or fried and, reverting to his own dietary customs, merely partook of a little salted and almost raw salmon. Lichtenberg bravely tried the dish, but it made him feel so ill that six hours later he had scarcely recovered from the effects. During and after the meal Solander entertained the gathering with familiar anecdotes. He repeated the story of their first meeting — in the coffee-house where Omai had stayed with Captain Furneaux on the night of their arrival — and confirmed the fact that, while the young native recognized Mr. Banks instantly and himself after some delay, they had no recollection of having seen him in Tahiti. He also spoke of Omai’s visits to the theatre but apparently said nothing of the point made by Miss Banks — that he refused to return to Sadler’s Wells because it was not patronized by the best people.12

Among miscellaneous observations, Lichtenberg noted that Omai’s teeth were ‘beautifully white, regular and well-formed’; that he had learned to play chess; that the name of his native island, as he spoke it, ‘sounded almost like Ulieta-ye’; and that he could not pronounce s, at least at the beginning of a word, for he rendered Solander as ‘Tolando’. Their conversation yielded novel particulars of Omai’s family:

I asked him whether his father and mother were still alive; he turned his eyes upwards, then closed them, and inclined his head to one side, giving us thereby to understand that they were both dead. When I asked him about his brothers and sisters, he first held up two fingers saying ladies, then three fingers saying men, thereby indicating two sisters and three brothers.

As for his mental attributes, they were not impressive in this critic’s opinion. He seemed to display little curiosity: he carried a watch but rarely troubled to wind it up and, while the rest of the company were looking at beautiful sketches of Pomona and other islands, Omai sat down by the fire and went to sleep. ‘It is much to be doubted’, Lichtenberg remarked, ‘whether he will become the Czar Peter the Great of his nation, notwithstanding that he undertook this journey in order to increase his reputation.’13

After Lichtenberg’s visit to New Burlington Street, nothing more was recorded of Omai for some weeks. Then, on 18 April, his presence was specially noticed by the General Evening Post at a gathering of high society to see the newly completed frigate Acteon launched at Woolwich. He was accompanied by the faithful Solander and for a time mingled with the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester, the Earl and Countess of Dartmouth, the Earl of Sandwich, and ‘other persons of distinction’ assembled for the event. Joseph Cradock, the First Lord’s musical friend, was also there and entered in his memoirs a trifling incident that throws further light on the domestic habits Omai had acquired during his sojourn. He was ‘very little entertained’ by the launching ceremony, Cradock relates. So, to relieve his boredom, he stole away to the neighbouring tavern and, ‘according to his custom, had very neatly cut the cucumbers and dressed the salad’ by the time his friends in their turn arrived for the meal.14

Some days later he was again in the news to more surprising effect. A brief paragraph in the London Chronicle began: ‘Omiah, the native of Otaheite, we are informed can read and write English well enough to hold a correspondence.’ What followed was even more startling: ‘It is still said he is going to be married to a young Lady of about 22 years of age, who will go with him to his own country.’15 The identity of the young lady remains a tantalizing mystery. This is the first and last reference to her in the Chronicle, and she is not mentioned by any of its contemporaries. Was she perhaps one of the ladies of easy virtue whose favours, there is reason to believe, Omai sought and won at some stage of his stay in London? Had he escaped the vigilance of his guardians to frequent (in Cook’s phrase) the purlieus of Covent Garden and Drury Lane? There is no certain answer. Up to this point he seems to have met only Miss Ray, Mrs. Burney and her step-daughters, the unnamed ladies of Leicester, and the womenfolk of his various hosts (but not certainly Miss Banks and her mother). Soon, however, he was to extend his acquaintance and enlarge his knowledge of sophisticated London society. If placed among the records of Omai’s equestrian exploits, the undated account of his legendary ride up the Oxford Road seems to belong to the spring or early summer of 1775 and marks his association with the Chevalier D’Eon, duellist, diplomat, and transvestite.

The story is told by Henry, eldest son of the fashionable fencing and riding master Domenick Angelo, friend of Reynolds, Garrick, and the dramatist George Colman. One day Henry, then in his late teens, set out with D’Eon and Omai from his father’s ‘manège’ in Carlisle Street, Soho, for the family’s country house at Acton. The trio, ‘mounted en cavalier, with cocked hats, long-tailed horses, and demie-queue saddles’, pranced in good style along the Oxford Road until they reached the Pantheon, about half way up. There, much to the amusement of the crowd, Omai’s horse came to a full stop, refusing to move, while D’Eon called out in French and the spectators shouted with laughter. Suddenly, ‘preferring the stable, and finding out what sort of a rider he had’, Angelo explains, the horse made for home. The Europeans rode on each side of their ‘whitey-brown companion’, using their whips, but in spite of their efforts his steed hurried back, with ‘poor Omai trembling from head to foot’. At last they reached Carlisle Street where a more docile mount was found that took Omai safely to Acton. ‘When I related the story’, Angelo lamely concludes, ‘it contributed very much to the amusement of my mother; not so of my father, who was angry with me for not telling him which rein to use.’16

Something might have been made of the limp anecdote by the creator of John Gilpin or perhaps by the satirists who indeed had again been active. Earlier in the year a contributor to the London Magazine wrote ‘On the Advantages which Great-Britain may derive from the Discoveries of Travellers in the Reign of his present Majesty’. Hawkesworth’s Collection and the Travels of Mr. Bruce need not, he held, serve merely to entertain the reading public; they could be of use to the nation at large. For example, Mr. Banks and Dr. Solander found that the people of Tahiti got on perfectly well without any kind of metal. What an advantage it would be to the British were they brought to the same situation. They would then be altogether independent of countries producing gold and silver; they would save the lives of many an unhappy wretch who falsified the coinage; and they would confer the blessings of health on their fellow citizens condemned to dig in mines or broil in forges. Again, since Tahitians managed perfectly well without horses, these animals could be slaughtered and the corn they ate distributed to the poor. True, this would eliminate cavalry, but surely English dragoons would be more suitably mounted on bulls trained for combat. The nation’s foes would then feel with a vengeance the force of the epithet ‘John Bull’, while no more effectual means could be devised for quelling the Bostonians. A further discovery of great utility had been brought from the same island: that it was perfectly natural to destroy children should they prove inconvenient. By adopting these excellent principles the British would, in a great measure, relieve themselves from the heavy burden of poor rates and make life easier and merrier for young people of both sexes. But New Zealand contributed a still more useful discovery, ‘certain intelligence of what was formerly considered by many to be fabulous — that mankind may feed even luxuriously upon the flesh of their own species.’ ‘Let us then’, urged the writer, ‘unite the child-murder of Otaheite with the eating of human flesh in New Zealand, and we shall realize the plan proposed by Dr. Swift for providing for the children of the poor in Ireland.’17

The next work was linked more closely to the Oberea cycle, though the monarch herself was nowhere mentioned by name. An Historic Epistle, from Omiah, to the Queen of Otaheite was published in the early summer of 1775 and dedicated by its professed ‘Editor’ to ‘JOSEPH B—NKS, Esq.’ ‘To whom’, he asked, ‘can a curiosity be offered with such propriety as to you, who have traversed the globe in search of them? Particularly this, which may be termed “A plant of your growth,” from the unremitting attention you have bestowed on OMIAH’S education; attention so wonderfully successful, that perhaps half the town will scarce believe this to have been entirely his own production.’ Was that a slyly sarcastic allusion to Banks’s failure, already voiced by Cullum, to improve his charge’s mind and morals? Here and there the anonymous author-editor does, in fact, seem to possess first-hand knowledge of the islander’s exploits. ‘Sometimes I ride’, Omiah proclaims — but his destination is Islington, not Acton. Perhaps he has the Chevalier D’Eon in mind when condemning ‘Macaronies’ ‘Whose only care is in ambiguous dress / To veil their sex ….’ He describes a contretemps at Court, not this time in greeting the King but when he attempts to seduce ‘A nymph … just ripe for amorous sport’ and is rejected, he supposes, through her fear of venereal disease (‘BOUGAINVILLE’S horrors’ in the text or ‘the Neapolitan fever’ as a footnote has it). Elsewhere he speaks of his visits to ‘the great Senate of the Realm’ and among its orators refers to ‘old CH-T-M’ with his ‘more than classic elegance of stile’.18

But the Historic Epistle is no mere versified chronicle of Omai in England; nor does it draw to any great extent on Hawkesworth. It is a satire, lengthier and more comprehensive than its predecessors, in which the ‘wand’ring vagrant in the northern world’ surveys the institutions of civilized society and finds them all wanting when measured by the ‘natural’ standards that prevail in the South Seas. He sums up his impressions in the opening pages:

Where’er I turn, confusion meets my eyes,

New scenes of pomp, new luxuries surprise ….

Then, using the artifices of European rhetoric, he emphasizes the contrast with his own unsophisticated island:

Can Europe boast, with all her pilfer’d wealth,

A larger share of happiness, or health?

What then avail her thousand arts to gain

The stores of every land, and every main:

Whilst we, whom love’s more grateful joys enthral,

Profess one art — to live without them all.

Similarly, in condemning the involved processes of English law he compares them with the simple precepts that determine southern justice:

Not rul’d like us on nature’s simple plan,

Here laws on laws perplex the dubious man.

Who vainly thinks these volumes are more strong,

Than our plain code of — thou shalt do no wrong.19

For the most part Omiah leaves his critical principles to be inferred. With only passing references to the virtues of his native sphere, he denounces the hypocrisies of established religion, the cruelties of European warfare, the pompous absurdities of the Law Courts, the corruption of art and letters (from which generalization he excepts the music of Handel and the painting of Reynolds). One of his main targets is science in all its eccentric manifestations. He attacks the impious probings of his hosts, the ‘Virtuosi’ of the Royal Society:

This wond’rous race still pry, in nature’s spite,

Through all her secrets, and Transactions write ….

He interprets Constantine Phipps’s northern expedition as a farcical and futile attempt to oil earth’s ‘axis at the pole’. He expends pages on the absurd theorizing of ‘Philogræcos’ with ‘his scientific prejudice for tails’ and in a footnote repeats a not implausible piece of gossip: When the famous Abyssinian traveller visited Edinburgh, he entered a court where the noble author was sitting in his judicial capacity; unable to restrain himself, the judge ‘sent a message with lord M—’s compliments, begging to be immediately informed, if he had seen any of the men with tails.’20

His own protectors and patrons are not exempt from Omiah’s satiric shafts. In a later section of the work he proclaims:

Know, through the town my guide S—L—ND—R goes,

To plays, museums, conjurers, and shows;

He forms my taste, with skill minute, to class,

Shells, fossils, maggots, butterflies, and grass ….

Banks is treated with similar indulgent derision in the prentice poet’s somewhat limping couplets:

O’er verdant plains my steps OPANE leads,

To trace the organs of a sex in weeds;

And bids like him the world for monsters roam,

Yet finds none stranger than are here at home.

Nor is ‘Religious S—NDW—CH’ spared in a ponderous quip ridiculing both his oratory and his arithmetical skill. The First Lord’s ungrateful protégé closes the epistle with a peroration that again contrasts degenerate Britain with his own uncorrupted island:

Sick of these motley scenes, might I once more

In peace return to Otaheite’s shore,

Where nature only rules the lib’ral mind,

Unspoil’d by art, by falsehood unrefin’d;

. . . .

There fondly straying o’er the sylvan scenes,

Taste unrestrain’d what Freedom really means:

And glow inspir’d with that enthusiast zeal,

Which Britons talk of, Otaheiteans feel.21

IN JUNE 1775, when the Historic Epistle was published, the supposed scourge of things British seems to have been quite happily reconciled to a further period of exile in the centre of all corruption. Since the beginning of the month he had again been enjoying naval hospitality, this time under the most distinguished auspices. He and Mr. Banks had been invited by Lord Sandwich to accompany him on the yacht Augusta during a ‘visitation’ or tour of inspection which took them to dockyards and depots as far distant as Plymouth. The impending departure of the yacht, its expected arrival at Portsmouth, and the First Lord’s return were briefly noted by the newspapers, but only his visit to Chatham was given more extended treatment. Here, reported the local correspondent, when arriving late on 4 June his lordship was saluted with fifteen guns by H.M.S. Ramillies, a compliment the Augusta returned with seven guns. The next morning Lord Sandwich came ashore with his party, including ‘Dr. Banks, and Omiah, the native of Otaheite’. Awaiting them were Commissioner Proby and the principal officers of the yard, while ‘the grenadier company of marines were drawn up before the Commissioner’s house, with drums beating, and fifes, and a band of music playing.’ The visitors then ‘took a view of the ships building and repairing, the storehouses, anchor wharf, &c.’ ‘Omiah’, the writer continued, ‘was conducted by Mr. Peake, builder’s assistant, on board the Victory of 100 guns, now repairing in the dock-yard; his joy was amazing at seeing so large a ship.’ The First Lord spent two more days inspecting vessels and men, after which he set out for Sheerness.22

The tour seems to have been a livelier, more informal affair than the newspaper report would suggest. Almost as if preparing himself for some lengthier expedition, Banks kept a minutely detailed ‘Journal of a Voyage Made in the Augusta Yatch Sr Richard Bickerton Commander’, beginning on the morning of 2 June when after breakfast at the Admiralty they left from the Tower. He was in holiday mood from the outset and in describing their passage to Greenwich tells how the Augusta ‘fell desparately in Love with a duch vessell’ so that Sir Richard was forced to anchor her ‘as a punishment for her Libidinous inclination’. There are many such pleasantries mingled with scientific jottings, nautical observations, and rather sparse allusions to the First Lord and the journalist’s fellow guests — the Earl of Seaforth, Omai, and two of Lord Sandwich’s staff, his secretary Mr. Bates, and an Admiralty official Mr. Palmer. Reaching Greenwich, they called at the hospital to eat heartily of ‘the best pease’ and drink as heartily of ‘the best small beer imaginable’ (‘the food of the old Pensioners’, Banks explained) and then passed on to the observatory. Here they found much that was curious but nothing more entertaining than the ‘Camera obscura’. Banks remained outside the chamber, thinking the exclamations of those inside sufficient amusement: Lord Sandwich’s recorded by a dash (too inaudible or possibly too improper to repeat); Lord Seaforth’s ‘a Cara’; and Omai’s ‘away te pereá’ (perhaps ‘aue! te piri e!’ or ‘Oh! how strange!’). In the afternoon they were joined by Miss Ray, Sir William Gordon, and other friends who had travelled from London by coach. Sailing ‘most merrily’ down the river, they all partook of dinner until at nine o’clock the visitors disembarked and the yacht continued on its way to Chatham.23

Banks mentioned the compliments paid by the Ramillies when they anchored off Chatham on 4 June and conscientiously recorded the events of the following day: the progress through yards and storehouses; the inspection of a variety of vessels — warships, a hospital ship, a church ship (not a word, however, of the Victory); and their last official duty, a visit to the victualling office. He praised the neatness and order prevailing throughout the depot and the dryness and airiness of the ships; but by the evening he had evidently satisfied his curiosity about naval affairs. Lord Sandwich, he wrote on the 6th, had ‘destind’ that day for mustering the yard, ‘a matter of infinite Consequence to him tho of no amusement to us’. So, borrowing a boat, he set out with his companions to explore the Medway. They admired successive sights — an old house ‘in a romantick situation’ commanding a view of Rochester castle and cathedral, the ruins of another house once, according to Camden, occupied by the Bishops of Rochester, a ‘very beautifull’ stretch of the river below the town. They also shot birds: gulls, herns, lapwings, and a turtle dove which they afterwards found juicy and good to eat. Sandwich continued his visitation on the 7th, but they had ‘seen enough of the old ships’, Banks again remarked, and preferred to spend the morning ashore watching artillery exercises. Later that day they rowed through the marshes, much amused by innumerable crabs ‘amorously inclind’, noting ‘the vigorous attempt of the males & the prudery of the females’. On rejoining the yacht in the evening, they heard a skylark serenade ‘as boldly as if it had been noon day’.24

A pattern had now been established for the tour. While the First Lord assiduously performed his official duties, Banks with equal assiduity followed his own interests, breaking off only on occasion to attend a formal reception or view a naval display. During his shore excursions he visited churchyards and castles and ruined abbeys and the homes of local gentlefolk. He was at particular pains to seek out and describe mechanical contrivances — at Sheerness a winch for drawing water from an enclosed well, at Hamble boat-shaped containers, fitted with wheels, to preserve lobsters and haul them ashore. He trawled for fish at sea, he angled in the rivers, he studied plants, he hunted wild life. Being ‘botanicaly inclind’, he wrote on 20 June, he left the yacht to find a rare species of grass mentioned in Ray’s synopsis of British plants. Three days later, as Lord Sandwich was detained at the Isle of Wight preparing dispatches, Banks went ‘a shooting’ birds with Lord Seaforth and Omai, all three setting out ‘a horseback’. Sometimes they picnicked — ‘dining in the air’ Banks called it — and more than once, at Omai’s request, they ended the day at a nearby theatre: ‘attended a play which Omai had bespoke’, ran an entry for 21 June. Again, at the end of the month, after a fruitless attempt to reach Eddystone lighthouse, Banks noted: ‘went to a play which Omai had bespoke’.25 This was the last time he named his protégé in the Augusta journal, and there were only three previous references. Perhaps his interest in Omai had indeed evaporated; on the other hand, since the other guests were mentioned no more frequently, he may merely have taken the young man’s presence for granted.

It was at this stage of the tour, while the Augusta was moored in Plymouth Sound, that the Admiralty received the first authentic intelligence of Cook since Furneaux’s return. On 27 June the General Evening Post, bemused as ever, announced that an express had come from Portsmouth with ‘news of the safe arrival of the Endeavour bark’. ‘Yesterday’, ran a note in the next issue, ‘a Messenger was dispatched to the Earl of Sandwich at Plymouth.’26 Actually, the Resolution was still in the Atlantic, a month’s sail from England, and what the messenger conveyed to the First Lord was a letter from Cook written at the Cape of Good Hope in March to report his landfalls and discoveries after parting with the Adventure. He spoke of Easter Island, the Marquesas, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, and went on to mention familiar places: Tahiti and the Society Islands, where for six weeks they again received ‘hospitality altogether unknown among more civilized Nations’; Rotterdam in the Friendly Islands, a briefer anchorage; and Queen Charlotte Sound, once more a haven and depot for nearly a month. He described yet another sweep through southern waters ‘strewed with Mountains of Ice’ and a second unsuccessful attempt to find Cape Circumcision. He praised the ‘constancy’ of officers and crew, paid a special tribute to ‘that indefaticable gentleman’ Mr. Hodges, and referred with a certain reserve to ‘other Gentlemen whom Government thought proper to send out’ (meaning, it seems, Mr. Forster and his son). ‘If I have failed in discovering a Continent’, Cook concluded, ‘it is because it does not exist in a Navigable Sea and not for want of looking ….’27

The letter was soon followed by one from Solander to Banks ‘on road from Portsmouth to Plymouth’. ‘As a Copy of Capt Cooks Letter was sent down to Ld Sandwich,’ he wrote, ‘I take it for granted you know all concerning his Voyage.’ His own special concern was with Odiddy, the Boraboran whom Cook had recruited at Raiatea and who, Solander’s inquiries and calculations led him to believe, was still on the Resolution. ‘If he should arrive before your return,’ he asked Banks, ‘shall it be mention’d to him, that Omai wishes he would live in the same house with him? It seems Mr Omai has desired Mr Vigniol to take him in, in case he should come.’ Reverting to the voyage, he remarked: ‘In all the Letters that are come from the Gentlemen on board the Resolution, they speak much in praise of our friends and all other Sth Sea Inhabitants that they have met with; and Nova Caledonia is described as a paradise without thorns or thistles.’ There followed excited impressions culled from a report sent by Mr. Forster: ‘260 new Plants, 200 new animals — 71° 10’ farthest Sth — no continent — Many Islands, some 80 Leagues long — The Bola Bola savage an [in]corrigible Blockhead — Glorious Voyage — No man lost by sickness.’ Solander sent greetings to his friends and a little personal news: Captain Phipps and he would represent Banks at a dinner on the Bessborough; he had seen Mrs. and Miss Banks that morning.28

In his Augusta journal Banks made no reference to these perhaps mortifying accounts of the Glorious Voyage he had forgone in a fit of pique. But he did full justice to the pleasures and minor triumphs that came his way during the last phase of the tour. The play which Omai bespoke at Plymouth on 30 June ‘turnd out the worst acted we had seen for some years’. Resolutely cheerful, Banks merely added: ‘as many of us were of opinion that plays should be either very well or very ill acted to be entertaining we went home not at all dissatisfied’. The next day, following two unsuccessful attempts, he landed on Eddystone, hardly a Nova Caledonia or even an island, yet full of interest, from its candle-powered lights to its pious keepers. After a spell of bad weather, they rowed up the Tamar on 4 July to enjoy the beauty of that ‘romantick’ river and dine with Lord Edgcumbe ‘in the true style of our ancestors’: ‘a more agreable day I never wish to Spend’, Banks remarked at its conclusion. Further diversions awaited them on their return to Plymouth: a dinner ashore and a final visit to the theatre on the 7th; and on the 8th an excursion to the Isle of Wight with local ladies and gentlemen — ‘the best contrivd & Executed as well as the most successful Party of pleasure I remember’, Banks commented. Rough seas, making everyone except Lord Sandwich ‘excessively sick’, marred the Channel passage, but by the 12th, as they approached Deptford, they were eating ‘in a quantity which would have done credit to a troop of his majesties beef eaters’. On the 13th ‘the Melancholy day of parting’ arrived and Banks ended both entry and journal with the eloquent: ‘I have been happy’.29

For the First Lord there was no immediate respite from his official labours. On 13 July ‘and not before’, as the General Evening Post expressed it, he returned to his house in the Admiralty after an absence of just six weeks spent in surveying the dockyards. He had found everything very satisfactory, the notice continued, ‘except the shipwrights, who have declined working till their wages are raised.’ In his account of their first stay at Portsmouth Banks referred in passing to ‘some little dissatisfactions’ in the yard. But the dispute was more serious than that suggests, for on the night of his arrival, the Post also noted, Lord Sandwich met other members of the Administration to consider how to set the men to work again, ‘as their absence from the dock-yards at this time is much felt.’ On the 14th, ran a further paragraph, he attended a levee at St. James’s and presented to His Majesty a list of ships and stores ‘by which it appears, that the royal navy is in very good condition.’ Nothing more was said of the striking workmen, and the tour was not again mentioned until the following week when the newspaper printed another startling announcement: ‘We hear that Omiah, since his return in the Augusta yacht, has been very bad from the sea sickness, so that there were but little hopes of his recovery.’30

The rumour was undoubtedly a libel on that seasoned navigator who had been sailing the seas since childhood and had recently traversed the oceans with no reported ill effects. Indeed, if published authorities are to be credited, he had already embarked on a further cruise in home waters. Banks’s biographers, regrettably failing to supply their evidence, all state with varying degrees of certainty that soon after the return of the Augusta Sandwich left on a second yachting excursion, this time with Miss Ray, Banks, Omai, Constantine Phipps, and perhaps his brother Augustus.31 Wherever they were (and, on the face of it, Hinchingbrooke would seem the most probable location), members of the little group were absent from London when the long heralded Resolution finally made its appearance.

WHILE HIS FRIENDS DIVERTED THEMSELVES, ashore or afloat, Solander stayed on in the capital, eagerly awaiting Cook’s return. On Friday 21 July he explained to John Ellis that he would be unable to visit him on the coming Sunday: he was ‘under an engagement’ to see the captain who was now daily expected.32 In the event he had to wait more than a week before sending Banks the dramatic and not quite accurate message: ‘This moment Captain Cook is arrived.’ He wrote at the beginning of August from some office or ante-room at the Admiralty where Cook, after his drive from Portsmouth, was closeted with his naval superiors. The explorer emerged in due course, looking ‘better than when he left England’, to pass on the warmest of greetings to Banks: nothing but his company, Cook said, could have added to the satisfaction he had in making the tour. He had some preserved birds for Banks’s collection, Solander also reported, and would have written himself ‘if he had not been kept too long at the Admiralty and at the same time wishing to see his wife.’ Odiddy, it appeared, had not made the voyage after all (he had been left at Raiatea), and Solander had to content himself with examining likenesses of Omai’s prospective fellow guest and potential rival — ‘really a handsome man’, he decided. The artist, Mr. Hodges, had produced a great many portraits, some very good; he seemed to be ‘a very well-behaved young Man’ and spoke with enthusiasm of the Tahitians and the Marquesans. Included in the letter were compliments to Miss Ray together with disjointed observations couched in a limited range of phrases: Solander had seen Cook’s maps; he called the group near Amsterdam ‘the Friendly Islands, because the people behaved very friendly’; those in the Hebrides were ‘not so friendly’ and he was ‘obliged to kill some’; Nova Caledonia was ‘a narrow strip of an Island’, its ‘People rather well behaved than otherwise.’33

Banks’s response to this exhilarating news is not on record; perhaps it may be inferred from the fact that he apparently made no attempt to join Solander but continued his summer excursion with Omai and other companions. Sandwich, on the other hand, parted from his guests to travel to London where his presence was soon observed in official circles. The newspapers, inured to such events, had expended little space on the return of the Resolution which they still confused with the Endeavour. They merely noted the ship’s safe arrival at Portsmouth and from its many landfalls and discoveries singled out for special mention ‘an island in the South Seas, in lat. 22’ (presumably New Caledonia) considered ‘the most eligible place for establishing a settlement, of any yet discovered’. On 10 August, however, the General Evening Post reported: ‘Yesterday Capt. Cook, who has lately been a voyage round the world, and made several discoveries in the South seas, was presented to his Majesty at St. James’s by Lord Sandwich, and most graciously received.’ The London Chronicle added that the captain made his own presentation of maps and charts and, further, that the Resolution was ‘to be repaired for another voyage’.34

News of the forthcoming voyage was quickly confirmed in a letter from Dr. Burney to the anxious James Lind who had asked to be advised of any such proposal. ‘When you last favoured me with a Letter’, the doctor wrote on the 12th, ‘I remember, & have constantly remembered that you wished to be apprised whether any new Expedition was in meditation for the South Seas.’ For some time, he had already apologized, ‘want of health & of Leisure’ had delayed his answer, while in addition, he now explained, there had been no positive information to impart:

I cd get no intelligence worth communicating sooner as nothing was resolved on during the absence of Capt. Cook; but now he is come home & has made considerable discoveries another Expedition is not only talked of, but determined to take place between this Time & next Xmas — I yesterday Dined at the Admiralty & had (I speak it inter nos) the Information from L. Sandwich himself. Two Ships are to be sent out, in one of wth I believe my Son, who has already been a circumnavigator wth Capt. Fourneaux, will go out Lieutenant.

James had recently spent a fortnight in England with the Cerberus which had returned to take on reinforcements and supplies for the hard-pressed British forces in North America. He had left again for Boston, his father told Dr. Lind, but was expected back in November and that, said Lord Sandwich, would be time enough for him to leave for the South Seas.35

Dr. Burney failed to mention the purpose of the new expedition; nor did he discuss the question of its leadership. The opinion then prevailing was that Cook’s first lieutenant would take charge. Mr. Clerke had been given the command, the General Evening Post announced a week later; and the Resolution, after refitting, would ‘prosecute’ further discoveries, ‘make a settlement on a large island in the South Sea, and carry back Omiah to Otaheite ….’36 Whatever the First Lord may have been meditating at this stage, Cook certainly had no thought as yet of a third voyage to the Pacific. Writing to his friend John Walker of Whitby on 19 August, he remarked that the Resolution would ‘soon be sent out again’ but emphasized, ‘I shall not command her’. For his part, he explained, he would be enjoying the ‘fine retreat’ and ‘pretty income’ ensured by the captaincy at Greenwich Hospital to which he had been appointed; whether he could bring himself ‘to like ease and retirement’, he added, time would show.37

Banks was kept abreast of these developments as he continued on holiday in the country. ‘Mr Clerke was promised the command of the Resolution to carry Mr Omai home’, wrote Solander on 14 August in describing a visit with Lord Sandwich to the ship, now moored in Galleon’s Reach. Their excursion, he said, was ‘quite a feast to all who were concerned’: setting out from the Tower, they visited the Deptford yard, took on ‘Miss Ray & Co’ at Woolwich, and then made their way to the Resolution. There the First Lord made many of the ship’s company ‘quite happy’ with his announcement of postings and promotions; not only Mr. Clerke but, among others, Captain Cook who was awarded a vacant place at Greenwich with ‘a promise of Employ whenever he should ask for it’. Most of their time, Solander explained, ‘was taken up in ceremonies’, but he was able to see something of the expedition’s trophies: ‘3 live Otaheite Dogs, the ugliest most stupid of all the Canine tribe’; ‘a Springe Bock’ with eagles and other birds, all brought from the Cape by Mr. Forster for presentation to the Queen; and, most diverting of spectacles, a severed head from New Zealand which ‘made the Ladies sick’. All their friends looked as well ‘as if they had been all the while in clover’ and all, Solander assured Banks, inquired after him: ‘In fact we had a glorious day and longd for nothing but You and Mr Omai.’ Compliments went to that gentleman and also to Captain Phipps and his brother.38

Not all visitors to the Resolution were so amiable. The anonymous author of ‘Harlequinade’, a chatty, semi-satirical commentary in the London Magazine, claimed to have spent an hour on the ship at Woolwich and to have examined ‘curiosities’ never seen in Europe before. Furthermore, he spoke to the ship’s officers about the last voyage and the coming one — with some surprising results. In their opinion the country best suited for settlement was New Zealand whose inhabitants were ‘sober, civil, tractable and kind’. True, they had killed and eaten crewmen of the Adventure; but, as they explained to Captain Cook, they were driven to that cannibal act ‘by the firing upon them unprovoked’; ‘indeed’, the writer commented, ‘no people, if not properly restrained by their officers, are more wanton in their wickedness than the English sailors.’ So it had been decided that ‘Omiah, the senseless stupid native of Otaheite,’ would be returned in the spring and the ship would then ‘proceed to settle New Zealand’. And who was to lead the enterprise? None other than Captain Cook whose ‘circumnavigable pursuits’ this voyage would terminate. Yet even the returned hero did not meet with the critic’s unqualified approval: his appointment as ‘conditional captain pensioner at Greenwich Hospital’ deprived ‘some veteran and infirm sailor of that situation.’ ‘But’, moralized this embryonic gossip columnist, now venting his spleen on Lord Sandwich, ‘some men in power leap over all rules and institutions; and dispose of places according to the pulse of interest, and the complexion of the times.’39

Cook himself seems to have been unaware of the new appointment so confidently predicted in the London Magazine. Writing again to John Walker in mid-September, he referred to the coming venture with no suggestion that he would take part. ‘I did expect and was in hopes’, he remarked, ‘that I had put an end to all Voyages of this kind to the Pacific Ocean, as we are now sure that no Southern Continent exists there, unless so near the Pole that the Coast cannot be Navigated for Ice and therefore not worth the discovery; but the Sending home Omiah will occasion another voyage which I expect will soon be undertaken.’ Nor was there the slightest hint of his own departure in a courteous letter he sent earlier in the month to a would-be Pacific explorer, Latouche-Tréville.40 He was particularly well disposed towards his French rivals as the result of an encounter during the homeward passage. Soon after reaching the Cape of Good Hope, he was fortunate enough to meet Captain Crozet, a man, as Cook described him, ‘possessed of the true spirit of a discoverer’ with ‘abilities equal to his good will’. This disinterested navigator not only supplied a chart showing the southern islands for which the Resolution and the Adventure had sought in vain but gave details of de Surville’s expedition and Marion du Fresne’s. After Aoutourou’s death and a stay at the Cape, Cook learned, Marion had made for New Zealand where he and many of his people were killed. Crozet spoke with authority, for he had been Marion’s second in command. And to some members of the ship’s company he related an historic sequel. In conversation with Rousseau, he had described the ‘behaviour of the New Zealand savages’; whereupon the philosopher ‘exclaimed, “Is it possible that the good Children of Nature can really be so wicked?”’41

However wicked in this instance, was the conduct of Pacific savages really more culpable than that of their civilized betters? One more contribution to the unending debate was a ‘Letter’ from a nameless ‘Officer of the Resolution to his Friend’, dated at Woolwich on 22 September and published in the London Magazine. Purporting to give an account of the voyage, he passed summarily over other anchorages to dwell on Tahiti. There, he assured his friend,

we have established a disease which will ever prove fatal to these unhappy innocents, who seem to have enjoyed a perfect state of simplicity and nature till we, a more refined race of monsters, contaminated all their bliss by an introduction of our vices. It is immaterial whether Bougainville or we communicated this disorder; but I am rather inclined to believe, by the account I had from the natives, that it came from the first English who touched at this spot.

While the islanders had medicinal roots which checked the disease, the writer continued, so high was their ‘venery’ that it increased daily — covered with sores, the victims died by inches. Worse still, it had now spread through the whole group, so that Borabora, ‘whilom the paradise of women’, was ‘an island of Pandora’s Ills’. The people, more particularly the Tahitians, had been very shy of the explorers and gave no presents, he reported, but he could not explain whether this was through a scarcity of supplies or a change of government; for ‘the courteous Oberea’ had been dethroned and lived in retirement with a small retinue. ‘The other circumstances of this island have been so often related before,’ the officer went on, ‘that I shall conclude with saying, that I blush for the honour of my country, which has suffered her people to destroy the happiest race of mortals ….’ His last word, however, concerned Omai: the voyager’s countrymen were looking out with impatience for his return and, though not a priest or a man of any distinction among them, ‘his exploring so far, will render him a prodigy ….’42

OMAI’S TRAVELS HAD EXTENDED EVEN FARTHER in the weeks since the Resolution’s return. On parting from Sandwich and Miss Ray early in August, Banks journeyed north with his friends until they reached York where they were joined by the playwright George Colman and his son, another George, then in his thirteenth year. After attending the races, they set off on an expedition which long remained in the memory of Colman the Younger and found a place in the diffuse and elaborately facetious reminiscences he aptly entitled Random Records. There were six in the party — the Colmans, Constantine Phipps, his youngest brother Augustus (a boy of George’s age), Omai, and his ‘bear-leader and guardian’, as Colman termed Banks. The ‘Otaheitan’, explained the author for the benefit of his nineteenth-century readers, had shown confidence in leaving ‘his flock, (for he was a priest,)’ to accompany ‘European Savages, on board the Adventure’ and, when he arrived, to entrust himself to someone ‘who had left a treacherous character behind him, in the South Seas’, a man who was reputedly ‘the “gay deceiver” of the Dido of Otaheite’.43

They ‘rumbled’ from York in a coach, the ‘ponderous property’ of Mr. Banks, ‘as huge and heavy as a broad-wheeled waggon’, yet not too huge for its contents. Besides the half-dozen inside passengers, it carried the luggage of Captain Phipps, ‘laid in like stores for a long voyage’: ‘boxes and cases cramm’d with nautical lore, — books, maps, charts, quadrants, telescopes, &c. &c.’ Even more formidable was Mr. Banks’s ‘stowage’: ‘unwearied in botanical research, he travell’d with trunks containing voluminous specimens of his hortus siccus in whitey-brown paper; and large receptacles for further vegetable materials, which he might accumulate, in his locomotion.’ Their progress, ‘under all its cumbrous circumstances’, was still further retarded by Mr. Banks’s indefatigable botanizing. They ‘never saw a tree with an unusual branch, or a strange weed, or anything singular in the vegetable world, but a halt was immediately order’d ….’ Then out jumped the botanist, out jumped the two boys, and out jumped Omai. This was the excursion Banks had forgone in the previous summer, and their destination was the Phipps family estate at Mulgrave near Whitby; but instead of taking the direct inland route they travelled by way of Scarborough. It was from an eminence near the town that they saw ‘the German Ocean’ and George had his first glimpse of the sea. He was hugely disappointed, he confessed, and ‘peremptorily pronounced’ it ‘nothing more than a very great puddle; — an opinion which must have somewhat astounded the high Naval Officer, who had not long return’d from his celebrated Voyage of Discovery towards the North Pole, and the Philosopher who had circumnavigated the globe.’44

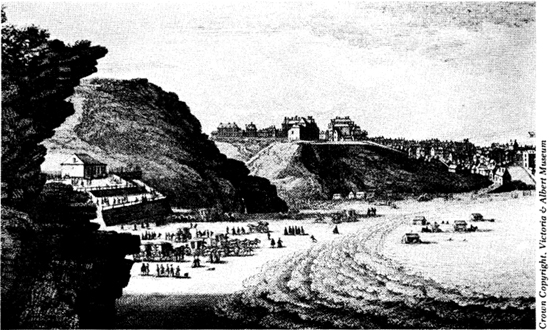

36 A view of Scarborough in 1745

On reaching Scarborough, George ran from the inn to the beach and early the next morning returned ‘to take a dip, as the Cockneys call it’. He was on the point of plunging in from a bathing-machine, he relates,

when Omai appear’d wading before me. The coast of Scarborogh having an eastern aspect, the early sunbeams shot their lustre upon the tawny Priest, and heighten’d the cutaneous gloss which he had already received from the water: — he look’d like a specimen of pale moving mahogany, highly varnish’d; — not only varnish’d, indeed, but curiously veneer’d; — for, from his hips, and the small of his back, downwards, he was tattow’d with striped arches, broad and black, by means of a sharp shell, or a fish’s tooth, imbued with an indelible die, according to the fashion of his country.

37 Mulgrave Castle, Yorkshire

Omai hailed George as ‘Tosh’ — he had, on Colman’s doubtful authority, greeted His Majesty with ‘“How do, King Tosh?”’ — and invited the boy to join him. George complied and, clinging to the islander’s back, set out, ‘as Arion upon his Dolphin’. But this Arion had no musical instrument to play, ‘unless it were the comb which Omai carried in one hand, and which he used, while swimming, to adjust his harsh black locks, hanging in profusion over his shoulders.’ His ‘wild friend’, Colman noted, ‘appear’d as much at home upon the waves as a rope-dancer upon a cord’ and safely delivered his passenger after spending three-quarters of an hour in the North Sea (the supreme test, surely, of Omai’s adaptability and physical stamina). Awaiting them on the shore were the other members of the party — Augustus, ‘vex’d’ that he was not with them, Colman Senior, a little grave at his son’s being so ‘venturous’, the captain and the philosopher, laughing heartily as they called George ‘a tough little fellow’. Henceforth, he wrote, Omai and he were constant companions.45

The friendship thus begun continued to flourish when they reached Mulgrave. The commander of the North Pole expedition and the visitor to the South Seas, disdaining any game more common than a penguin or a bear, left the grouse on neighbouring moors to hired keepers. But Omai entered into the sport with abandon. Now quite familiar with European weapons, he ‘prowl’d upon the precincts’, gun in hand, popping at ‘all the feather’d creation which came in his way; and which happen’d, for the most part, to be dunghill cocks, barn-door geese, and ducks in the pond.’ Sometimes, as Colman tells, he reverted to his own more primitive methods of hunting:

One day, while he carried his gun, I was out with him in a stubble field, (at the beginning of September,) when he pointed to some object at a distance, which I could not distinguish; — his eye sparkled; he laid down his gun mighty mysteriously, and put his finger on my mouth, to enjoin silence; — he then stole onwards, crouching along the ground for several yards; till, on a sudden, he darted forward like a cat, and sprang upon a covey of partridges, — one of which he caught, and took home alive, in great triumph.

His treatment of other livestock could be quite as ungentlemanly. On another occasion, ‘with the intent to take a ride’, he seized a grazing horse by the tail, whereupon ‘the astounded animal gallop’d off, wincing and plunging, and dragging his tenacious assailant after him, till he slipp’d from his grasp’, leaving Omai in the mire but miraculously unhurt. ‘He was not always so intrepid;’ Colman continues, ‘— there was a huge bull in the grounds, which kept him at a respectful distance; and of which he always spoke reverentially, as the man-cow.’46

Encouraged by George, Omai continued his efforts to master English, while he in turn introduced the boy to his native tongue: ‘reciprocally School-master and Scholar’, they began by pointing to objects which each named in his own language. From words they advanced to phrases and short sentences until at the end of the first week they could hold something like a conversation, ‘jabbering to each other between Otaheitan and English.’ At the same time, under the tutelage of their elders, the two boys were extending their knowledge in other directions. Banks explained the rudiments of the Linnaean system in a series of nightly lectures, the first of which he illustrated by cutting up a cauliflower, and early every morning sent them to gather plants in the woods. Captain Phipps for his part organized expeditions to open ‘the tumuli, or Barrows, as they are vulgarly call’d’. Since their archaeologizing took place at some distance from the house, they dined in a tent on dishes which they prepared themselves. Banks made very palatable stews in a tin machine, but ‘the talents of Omai shone out most conspicuously; and, in the culinary preparations, he beat all his competitors.’ As before at Hinchingbrooke, he built an earth oven to practise ‘the Otaheitan cuisine’, using English substitutes for native commodities: ‘he cook’d fowls instead of dogs …. for plantain leaves, to wrap up the animal food, he was supplied with writing paper, smear’d with butter; — for yams, he had potatos; for the bread fruit, bread itself, — the best homemade in Yorkshire.’ Nothing, Colman decided, could have been ‘better dress’d, or more savoury’ than Omai’s dish; and he singled out for praise the special flavour, that ‘soupçon of smokiness’, imparted to the fowls by ‘the smouldering pebble-stones and embers of the Otaheitan oven’.47

One of Captain Phipps’s guests lost no time in writing of their bucolic pleasures and exotic repasts to a friend who was equally prompt in his reply. ‘My dear Colman,’ David Garrick addressed the playwright on 29 August, ‘I expect to see you as brown and as hearty as a Devonshire plough-boy, who faces the sun without shelter, and knows not the luxury of small beer and porter.’ He sent compliments to ‘those mighty adventurous knights’, Banks and Phipps, if Colman was still risking his neck with them, and referred knowingly to their rustic feasts: ‘I must lick my fingers with you, at the Otaheite fowl and potatoes; but don’t you spoil the dish, and substitute a fowl for a young puppy?’ He passed on obscure items of theatrical gossip — Foote had thrown the Duchess of Kingston ‘upon her back’ (in his Trip to Calais), Miss Pope the actress had sent her ‘penitentials’ — and spoke hopefully of his infirmities. He had been upon the rack since Colman left him, Garrick confessed, but at the Duke of Newcastle’s an old Neapolitan friend commended a remedy which had worked wonders. Now his spirits were returned and he even meditated authorship on his own account. ‘By the bye’, he announced, ‘I had some thoughts to make a farce upon the follies and fashions of the times, and your friend Omiah was to be my Arlequin Sauvage; a fine character to give our fine folks a genteel dressing.’48

THE GAY LITTLE COMPANY was dispersed by mid-September, just before Constantine Phipps succeeded his father as the second Baron Mulgrave and inherited the family estate.49 By that time Omai was back in London, but until December there is a complete gap in the record of his doings save for one brief reference. In a letter written on 19 September to Edward Wortley Montagu at Venice, the physician and naturalist William Watson reported that he had dined twice with Captain Cook and was ‘happy in hearing his relation.’ Most of what the doctor heard covered familiar topics: the expedition had added greatly to knowledge of the globe; it had found no Terra Australis; it had brought back new plants and animals. Cook also dwelt on his two visits to Tahiti, making special mention of the native (Odiddy) he had picked up and returned; and he spoke with awed admiration of the great fleet gathered by the Tahitians, just before the Resolution sailed, to attack a neighbouring island — he thought it ‘the finest Spectacle he ever Saw.’ ‘The whole account of this voyage’, Watson continued, ‘is, I am told, preparing for publication by Capt Cook, & Mr Forster, who, as Mr Banks & Dr Solander declined going, went in the capacity of a naturalist.’ Winding up the bulletin, he sent the absent Montagu news of the next expedition:

Mr Clark, who came home Capt Cook’s lieutenant, is, it is believed, to be appointed to a command, & Sent home with Omay, who is now So far acquainted with this country, that not long Since, & without any body attending him, he hired a horse, & rode to visit Baron Dimsdale, by whom he was inoculated, at Hartford.50

Omai’s self-reliance was also mentioned by Fanny Burney when, on 14 December, she entered in her diary a lengthy account of his unexpected call at Newton House late one evening as the family entertained another guest, Miss Lidderdale of Lynn. He now walked everywhere quite alone, she wrote, and lived by himself in lodgings at Warwick Street, supported by a pension from the King. Since his first visit, twelve months before, he had, she noted, learned a great deal of English and, with the aid of signs and actions, could make himself tolerably well understood. He pronounced the language differently from other foreigners, sometimes unintelligibly, but he had really made great proficiency, considering the disadvantages he laboured under; for he knew nothing of letters, while so very few persons were acquainted with his tongue that it must have been extremely difficult to instruct him at all. Though magazine scribblers might censure Omai for his stupidity, Fanny was not of their opinion. On the contrary she spoke of him as ‘lively and intelligent’, praising him further for the ‘open and frank-hearted’ manner with which he looked everyone in the face as his friend and well-wisher. ‘Indeed, to me’, she remarked, ‘he seems to have shewn no small share of real greatness of mind, in having thus thrown himself into the power of a nation of strangers, and placing such entire confidence in their honour and benevolence.’51

38 Newton House

In spite of goodwill on both sides, communication was not easy. ‘As we are totally unacquainted with his country, connections, and affairs,’ Fanny primly explained, ‘our conversation was necessarily very much confined; indeed, it wholly consisted in questions of what he had seen here, which he answered, when he understood, very entertainingly.’ The first person discussed was Omai’s friend James:

He began immediately to talk of my brother.

‘Lord Sandwich write one, two, three’ (counting on his fingers) ‘monts ago, — Mr. Burney — come home.’

‘He will be very happy,’ cried I, ‘to see you.’

He bowed and said, ‘Mr. Burney very dood man!’

We asked if he had seen the King lately?

‘Yes; King George bid me, — “Omy, you go home.” Oh, very dood man, King George!’

He then, with our assisting him, made us to understand that he was extremely rejoiced at the thoughts of seeing again his native land; but at the same time that he should much regret leaving his friends in England.

‘Lord Sandwich,’ he added, ‘bid me, “Mr. Omy, you two ships, — you go home.” — I say (making a fine bow) “Very much oblige, my Lord.”’52

Their later conversation, covering a variety of topics, threw some dim light on Omai’s occupations and diversions in the weeks since his return from Yorkshire. When they asked how he liked the theatres, he failed to understand, ‘though, with a most astonishing politeness,’ Fanny commented, ‘he always endeavoured, by his bows and smiles, to save us the trouble of knowing that he was not able to comprehend whatever we said.’ He made no mention of the excursion to Hertford or his other equestrian feats, but amused the company (and apparently himself) by a description of pillion riding which Fanny supposed he had seen on the roads: ‘“First goes man, so!” (making a motion of whipping a horse) “then here” (pointing behind him) “here goes woman! Ha! ha! ha!”’ Miss Lidderdale, who was dressed in a habit, told him she was prepared to go on horseback, whereupon he made a very civil bow and, displaying his knowledge of genteel usage, reassured her, ‘“Oh you, you dood woman, you no man; dirty woman, beggar woman ride so; — not you.”’53

They went on to speak of Fanny’s half-brother Dick. Omai remembered him from his previous visit and when told he now went to school at Harrow, ‘cried, “O! to learn his book? so!” putting his two hands up to his eyes, in imitation of holding a book.’ He then attempted to describe a school to which he had been taken and, prompted by Miss Lidderdale, discussed the friends he had made in aristocratic circles:

‘Boys here, — boys there, — boys all over! One boy come up, — do so!’ (again imitating reading) ‘not well; — man not like; man do so!’ Then he showed us how the master had hit the boy a violent blow with the book on his shoulder.

Miss Lidderdale asked him, if he had seen Lady Townshend lately?

‘Very pretty woman, Lady Townshend!’ cried he; ‘I drink tea with Lady Townshend in one, two, tree days; Lord Townshend my friend, Lady Townshend my friend. Very pretty woman, Lady Townshend! Very pretty woman, Mrs. Crewe! Very pretty woman, Mrs. Bouverie! Very pretty woman, Lady Craven!’

We all approved his taste; and he told us that, when any of his acquaintances wished to see him, ‘they write, and bid me, Mr. Omy, you come, — dinner, tea, or supper, then I go.’54

Of all the subjects considered that evening the one nearest the Burneys’ collective heart was music. When someone asked Omai whether he had been to the opera, ‘He immediately began a squeak, by way of imitation, which was very ridiculous; however, he told us he thought the music was very fine, which, when he first heard it, he thought detestable.’ Dr. Burney, who was absent when the visitor first arrived but returned later, asked him to repeat a song of his own country which he had sung at Hinchingbrooke. Omai complied but only with reluctance:

He seemed to be quite ashamed; but we all joined and made the request so earnestly, that he could not refuse us. But he was either so modest, that he blushed for his own performance, or his residence here had made him so conscious of the barbarity of the South Sea Islands’ music, that he could hardly prevail with himself to comply with our request; and when he did, he began two or three times, before he could acquire voice or firmness to go on.

The song appeared to be ‘a sort of trio’ involving an old woman, a girl, and a youth. The two latter are entertaining each other with ‘praises of their merits and protestations of their passions’ when the woman enters and ‘endeavours to faire l’aimable to the youth’, displaying her dress and ‘making him admire her taste and fancy’. He ‘avows his passion for the nymph’; the old woman sends her away and, ‘coming forward to offer herself, says, “Come! marry me!” The young man starts as if he had seen a viper, then makes her a bow, begs to be excused, and runs off.’ Fanny was full of admiration for Omai’s mimic talents. The ‘grimaces, min-auderies, and affectation’ he assumed when impersonating the old woman, for example, afforded them ‘very great entertainment of the risible kind’. On the other hand, the vocal side of his performance offended her sensitive ears. ‘Nothing’, she wrote, ‘can be more curious or less pleasing than his singing voice; he seems to have none; and tune or air hardly seem to be aimed at; so queer, wild, strange a rumbling of sounds never did I before hear; and very contentedly can I go to the grave, if I never do again.’ Her considered verdict on Omai was: ‘His song is the only thing that is savage belonging to him.’55

Fanny may not have been the only member of her family to comment on their guest’s singing. In the Royal Society’s Transactions for 1775 there appeared a review of two papers by the learned Joshua Steele on musical instruments brought back by Captain Furneaux. While praising Mr. Steele for his ‘minuteness of investigation’ and the ‘profusion of ancient musical erudition’ he displayed, the anonymous writer considered the subject ill adapted to so laboured a treatment. The ‘arbitrary, and indeterminate sounds, given by the reed pipes of the barbarous islanders of the South Seas’ which, he affirmed, could be produced by blowing through a penny whistle, were ‘here seriously, and scrupulously, compared with the diatonic and chromatic genera of the polished Greeks.’ Indeed, were the author not perfectly serious throughout, the two papers might seem intended as a ‘solemn mockery of ancient wisdom’. Yet, the reviewer conceded, the Tahitians did ‘practise the intervals of the diesis, and still minuter divisions of the tone’; and in support of his assertion he cited ‘the testimony of a sober and discreet person, who has a tolerable good ear, and has heard Omiah sing one of his country songs.’ According to this witness, ‘The melody … seemed to be wholly enharmonic — slubbering and sliding from sound to sound by such minute intervals, as are not to be found in any known scale, and which made it appear to him as music, — if it could be called music, of another world.’ Evidence for the authorship of these remarks all points in one direction. The style, with its mingling of the technical and the colloquial, is close to Dr. Burney’s; moreover, he had been elected to a fellowship of the Royal Society the previous year and early in 1776 would publish the first volume of his History of Music, much of it concerned with the Greeks. Thus it is more than likely that both reviewer and discreet person were none other than Dr. Burney himself and that the article conveys the impressions he had formed at Hinchingbrooke and St. Martin’s Street.56

Omai sang no more for the Burneys. When he next appeared at Newton House late in December he was accompanied by Mr. Andrews, a gentleman who was hitherto unknown to Fanny and who, she said, spoke Tahitian very well. This, she complained, they had reason to regret, as it rendered their guest far less entertaining than during his previous call when he was obliged, in spite of the difficulties, to explain himself as well as he could. Now, with Mr. Andrews ready as interpreter, he gave himself very little trouble to speak English. Omai was, of course, no longer a novelty and in any case this latest visit was overshadowed by a more momentous event recorded in the same entry of Fanny’s diary. ‘My brother James,’ she wrote, ‘to our great joy and satisfaction, is returned from America, which he has left in most terrible disorder.’ He was extremely well in health and spirits, she reported, and though suffering great hardships, had nevertheless honourably increased his friends and gained in reputation. He was, she concluded, in good time for ‘his favourite voyage to the South Seas’ which was to ‘convoy’ his friend Omai home and would, they believed, take place in February.57

Time was indeed running out. When the year ended, Mr. Banks or his book-keeper drew up a second financial statement, ‘Expences incurrd on account of Omai in the Course of the Year — 1775’. The largest single item was £160-0-0, being ‘One Years Board & Lodging for Himself and Mr Andrews’ paid to ‘Mr De Vignolles’ and already authorized by Lord Sandwich in August 1774. (Mr. Andrews’s emolument seems to have been more than adequate since his only recorded appearance as escort was at St. Martin’s Street.) Omai’s landlord also received £6-14-0 for ‘Necessaries laid in, when he came into his Lodgings’ and a further £18-4-1 for ‘Necessaries’ bought later in the year. One composite item, ‘Money advanced by me’, covered Banks’s allowance to his charge, varying from quarter to quarter: ten guineas for the first, sixteen for the second, five for the third (mainly taken up by the Augusta cruise and the northern tour), and fifteen for the last. ‘Cash Advanced by Lord Sandwich’ was a modest two guineas, while ‘Roberts’ (presumably Banks’s servant) received £2-19-6½ for undisclosed services. This account was more explicit than the first regarding Omai’s transactions with various tradesmen: his ‘Taylors 2 Bills’ amounted to £52-0-4, and he spent £16-10-0 on wine; among lesser items, £3-13-0 went to his hairdresser, £4-0-0 to his shoemaker, and three guineas to his apothecary. The total amounted to the not inconsiderable sum of £317-11-11½, and on this occasion there was no credit entry. Perhaps his patrons had reason for urging, ‘Omy, you go home.’58