MEANWHILE OMAI HAD SET OUT ON HIS SECOND OCEAN VOYAGE, NOT consigned this time to the crew’s quarters of the escorting vessel but accommodated in the Resolution as an honoured charge of the commander. On the road from London to Chatham, Cook related, the young man was moved by ‘a Mixture of regret and joy’. When they spoke of England and of those who had honoured him with their protection and friendship, he became very low-spirited and with difficulty refrained from tears; ‘but turn the conversation to his Native Country and his eyes would sparkle with joy.’ He was, in the captain’s opinion, ‘fully sencible of the good treatment he had met with in England and entertained the highest ideas of the Country and people.’ On the other hand, ‘the prospect he now had of returning home to his native isle loaded with what they esteem riches, got the better of every other consideration and he seemed quite happy ….’ They had left London at six o’clock on the morning of 24 June and some five hours later arrived at Chatham where Omai’s acquaintance Commander Proby entertained them at dinner and very obligingly arranged for his yacht to take them to Sheerness. There they boarded the Resolution and about noon the next day set sail. On the 26th they anchored off Deal to pick up two boats, but Omai did not go ashore, ‘to the great disapointment’, Cook recorded, ‘of many people who I was told had assembled there to see him.’ Soon he was on the best of terms with his new shipmates. ‘Omiah is a droll Animal & causes a good deal of Merriment on Board’, wrote David Samwell, the surgeon’s mate, on the 29th. At the end of the month they reached Plymouth, only three days behind the Discovery.1

During his brief stay in port Cook busied himself with last-minute preparations and took on board supplies to replace those already expended. On 8 July he received ‘by express’ his ‘Secret Instructions’ which contained little that was novel since they had obviously been drawn up with his knowledge and embodied his own views and plans. He was first to make for the Cape of Good Hope, calling if necessary at Madeira, the Cape Verde, or the Canary Islands to purchase wine. Having refreshed his men and provisioned his ships at the Cape, he was to seek out the southern islands recently discovered by the French and examine them for harbours and other facilities that might aid shipping.

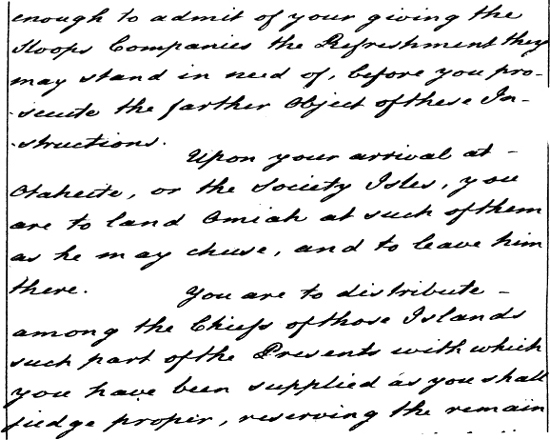

42 From Cook’s secret instructions

Next, after touching if convenient at New Zealand, he was to carry out his first mission. ‘Upon your arrival at Otaheite, or the Society Isles,’ he was enjoined, ‘you are to land Omiah at such of them as he may chuse and to leave him there.’ He was then to commit himself to his second objective, the attempt to find a passage, either to the north-west or the north-east, from the Pacific to the Atlantic or the North Sea. The minutely detailed document included a wildly optimistic timetable, warned Cook against offending the Spaniards, and anticipated every contingency save the one that ultimately overtook the expedition and himself.2

In his punctilious fashion Cook reported receipt of the instructions and, as the fleeting interlude drew to a close, discharged his obligations to subordinates, friends, and patrons. Clerke, still detained by minions of the law in London, was informed of the Resolution’s imminent departure and directed on his release to follow ‘without a moments loss of time’. Sandwich received effusive acknowledgements for his many favours, in particular for the very liberal allowance made to Mrs. Cook. ‘This,’ wrote her husband, ‘by enabling my family to live at ease and removing from them every fear of indigency, has set my heart at rest and filled it with gratitude to my Noble benefactor.’ The Revd. Dr. Kaye of St. James’s Palace was likewise thanked for his kind tender of service to Mrs. Cook and assured that his name would be commemorated should it please God to spare Dr. Kaye’s humble servant. Banks in turn was favoured with a letter largely taken up with his part in preparing the new publication for the press. Cook was obliged for these services and in addition, he said, for the ‘unmerited Honor’ conferred on him by the award of the Royal Society’s medal. Of his charge he wrote amiably: ‘On my arrival here I gave Omai three guineas which sent him on shore in high spirits, indeed he could hardly be otherwise for he is very much carressed here by every person of note, and upon the whole, I think, he rejoices at the prospect of going home.’ He only waited for a wind to put to sea, Cook added, and in conclusion sent Dr. Solander and Mr. Banks his best respects in which he was joined by Omai.3

By the evening of 12 July 1776 the wind was favourable and, delivering Clerke’s sailing orders to Lieutenant Burney, Cook set out. So it was that Omai left England almost exactly two years after his arrival with Captain Furneaux. Having acted as the agent of providence, that veteran of the South Seas had again taken up regular service and was now winning modest renown in American waters. His ship the Syren, ran a recent announcement from the Admiralty, had captured a brigantine carrying rebel troops from Philadelphia to Charleston. The news afforded some slight encouragement to counter the gloomy bulletins that continued to cross the Atlantic. As Townshend had mentioned in his ode, the British forces had been compelled to abandon the town of Boston, while the fate of Quebec still hung in the balance. But the government was marshalling its forces to quell disaffection. While he lay at Plymouth, Cook noted the arrival of a flotilla, driven into the Sound by adverse winds. Made up of His Majesty’s ships, Diamond, Ambuscade, and Unicorn with sixty-two transports, it was bearing to America a division of Hessian troops and their mounts.4

Committed to a more peaceful mission on his country’s behalf, Cook followed an uneventful course for the next four weeks. At this early stage of the voyage the live cargo for the Pacific was already influencing his actions. Finding that the hay and corn on board would be insufficient until they reached the Cape, he decided to call at Tenerife where he thought the fodder would be more plentiful than at Madeira. He anchored in the roadstead of Santa Cruz on 1 August and until the 4th busied himself attending to the needs of his voracious animals and his crew. Supplies were plentiful and, though the local wine was to his taste far inferior to the best Madeira, he found it much cheaper. While he and some of his officers dealt with purveyors or paid official calls, others were at leisure to inspect the sights. One afternoon Mr. Anderson with three companions hired mules to take them to the city of Laguna, a disappointing excursion enlivened by the cheerful songs of their guides. The surgeon was impressed by the island’s remarkably healthy climate and wondered why consumptive patients were not sent here rather than to Lisbon. He admired the dark-clad, dark-eyed women and noted that, while the British saw no marked similarity between their own ways and those of the Spaniards, Omai did not think the difference great: ‘He only said they seem’d not so friendly & in person they approach’d those of his own country.’5

They continued on their way, narrowly escaping disaster on a submerged reef in the Cape Verde Group where Cook decided to call in case their consort awaited them at St. Jago. A brief inspection of the shipping anchored off the island showed that the Discovery was not there, so on 16 August they turned again to the south. Within a week they were well inside tropical waters and Omai had the first chance to display his native talents. Not only had he shown his shipmates how to catch dolphins with a white fly and rod, Cook observed on the 23rd, but he hooked twice as many of the fish as anyone else. Anderson also called on the versatile supernumerary to identify a novel species of shark. He was able to supply its Tahitian name, adding that it was considered the best to eat, far superior to the shore variety. When the ship crossed the line at the beginning of September, as one of the veterans Omai was presumably exempt from what the enlightened Anderson called ‘the old ridiculous ceremony of ducking’. Because of scamped workmanship in the royal dockyards the final weeks passed in damp discomfort. Rain poured through the badly caulked decks and sea water invaded the cabins. It was with relief that they sighted the Cape on 17 October and early the next afternoon anchored in Table Bay.6

David Samwell for one had no complaints. It had been a pleasant passage, he informed his friend Matthew Gregson on the 22nd, and as this was ‘a very plentiful Country’ they would live on ‘the Fat of the Land’ for the next month. Then they would set off for Tahiti where he supposed they would not stay long since they must use the summer season to try for the North-West Passage. And if that was found, they would be back in England by the following winter. He went on to give impressions of his fellow passenger based on more than three months’ observation:

Omiah is very hearty and I do not doubt but he will live to see his own Country again, he is not such a stupid fellow as he is generally look’d upon in England, ‘tis true he learn’d nothing there but how to play at cards, at which he is very expert but I take it to be owing more to his want of Instruction than his want of Capacity to take it. he talks English so bad that a person who does not understand something of his language can hardly understand him or make himself understood by him they have made him more of the fine Gentleman than anything else, he is a good natur’d fellow enough, and like all ignorant People very superstitious, Seeing on our Passage here a very bright Meteor pointing to the Northward, he said it was God going to England & was very Angry that anyone should offer to contradict him, looking upon it as no less than Blasphemy.

He himself was now on shore, Samwell explained, living in a tent near the town which was without exception the most beautiful he had ever seen. ‘Today’, he proudly announced, ‘Capt. Cook din’d with the Governor at the Garrison — 3 royal Salutes of 21 Guns each were given with the Toasts at Dinner.’ The governor and everyone else, Samwell added, paid the captain extraordinary respect; he was as famous here as in England and perhaps even more noted.7

While he discharged official and social obligations, Cook also attended to his pressing duties as leader of the expedition. At first the site chosen for an encampment was occupied by local militiamen, but he set the caulkers to work on the leaky Resolution and with the aid of his old friend Mr. Brand ordered supplies from various purveyors. By the 23rd he had set up tents for sailmakers and coopers, brought the animals ashore to graze, and begun taking astronomical measurements in his observatory. That day he addressed to Sandwich a short letter which he sent off by a French Indiaman leaving for Europe. ‘My Lord’, he began, ‘Before I sailed from England your Lordship was pleased to allow me the Honour of Writing at all oppertunities.’ He now embraced this one, he wrote, to inform his lordship of his safe arrival with Omai and the animals, all ‘in a fair way of living to arrive at their destined spot’. The Discovery had not yet joined them, he reported, but that very moment a ship had been signalled and was probably their consort. ‘Omai’, he concluded, ‘desires his most dutifull respects to your Lordship, and I am well assured it is from the sincerity of his heart, for no man can have a more juster sence of your Lordships favours except Your Lordships most Obedient & faithfull Humble Servant Jams Cook’. A postscript followed: ‘I am just told that the ship in the offing is too large for the Discovery.’8

Clerke did not in fact reach Cape Town until 10 November. He had made a swift passage and would have arrived at least a week earlier but for a storm which also caused havoc in the Resolution’s shore station and nearly ruined the astronomical quadrant. Nor was this the last of their misfortunes. On the night of the 13th ‘some person or persons’, as Cook judicially expressed it, put dogs among the sheep penned near the encampment, killing four and dispersing the rest. In the governor’s absence, the incident was reported to his deputy Mr. Henny (or Hemmy in Cook’s version) and the public prosecutor. Both ‘gentlemen’ promised to ‘use their best endeavours’ to have the animals found; ‘and’, Cook darkly commented, ‘I shall beleive they did when I am convinced that neither they nor any of the first people in the place had any hand in this affair.’ In the end by bribing ‘the meanest and lowest scoundrels’ he succeeded in recovering most of the sheep and bought a few more of the Cape variety. Mr. Henny, evidently a farmer or breeder on his own account, ‘very obligingly’ offered to replace an injured ram by one he had imported from Lisbon, but the offer was declined. From his lavish use of sarcasm and innuendo it becomes obvious that Cook suspected the deputy governor of coveting the royal flock and using these despicable measures to make it his own.9 Mr. Henny again figures in the annals of the voyage through his association with a relic of slightly more than antiquarian interest. While visiting the house he owned or occupied at the time, Omai and Clerke scratched their autographs on one of the windows. The inscriptions survived for many years and in the late eighteen-fifties, when the building had become the property of the South African Bank, efforts were made to transfer the pane to the local museum. It has since vanished and with it perhaps the only authentic evidence that Granville Sharp had not laboured in vain.10

In spite of the fame or notoriety Omai now enjoyed, the early weeks of his second visit to the Cape are but sparsely recorded. Was the incision on Mr. Henny’s window the climax of some riotous evening or was it perhaps a ceremony carried out on a more formal occasion? And did the young dandy array himself in velvet suit and dress sword to call on the Dutch lady who had won his regard (but not his love) in 1774? One can merely speculate. There is some slight evidence, however, that he made a lasting impression on the daughters of Mr. Brand, and towards the end of his stay explicit references to his actions become more frequent. From 16 November until the 20th he was one of a small party that went to the district north-east of Cape Town to collect specimens for Mr. Banks. His companions included David Nelson, the Discovery’s supernumerary, Lieutenant Gore, and Mr. Anderson who wrote to the botanist on the 24th to tell him of the excursion. The results, he had to confess, were disappointing. Their two ‘shooters’, Mr. Gore and Omai, had with the utmost diligence only killed a few small birds. Nor had Nelson had much success in gathering botanical samples, for at this time of the year not many plants were in flower. ‘Omai has just desired me to present his respects to you’, he informed Banks, concluding with the abrupt disclosure: ‘He brought a pox with him but is now well.’ Evidently Omai was not alone in his affliction. On leaving Plymouth they had ‘a little of the Small and abundance of the French Pox’ but all hands were again ‘perfectly healthy’, wrote Clerke when reporting to Banks his arrival at the Cape and imminent departure.11

More discreet than Anderson and Clerke, Cook ignored medical details in the letters he sent on the eve of sailing. At length they were ready to put to sea, he informed Lord Sandwich on the 26th. Nothing was wanting, he jested, ‘but a few females of our own species to make the Resolution a Compleat ark’; for he had taken the liberty of adding considerably to the number of animals transported from England; but, as he had done so for the good of posterity, he had no doubt the measure would meet with his lordship’s approbation. ‘The takeing on board some horses has made Omai compleatly happy’, he added; the obliging passenger had ‘consented with raptures’ to give up his cabin in order to make room for the new arrivals, his only concern being that there would not be enough food for all the stock they carried. ‘He continues to in joy a good state of health and great flow of Spirits’, Cook reported, ‘and on every occasion expresses a thankfull rememberence of your Lordships great kindness to him.’ The captain went on to assure Sandwich that his lordship’s efforts had not been lost on Omai who, during his stay in England, had obtained ‘a far greater knowlidge of things than any one could expect or will perhaps believe.’ ‘Sence he has been with me’, the tribute ended, ‘I have not had the least reason to find fault with any part of his conduct and the people here are surprised at his genteel behaviour and deportment.’ The same day similar pleasantries and sentiments went to Mr. Banks who was desired to receive Omai’s best respects for himself and convey them to Dr. Solander, Lord Seaforth, and ‘a great many more, Ladies as well as Gentlemen’. Their names he could not insert, Cook explained, because they would fill up the whole sheet of paper.12

At the end of November the two ships at last weighed anchor and sailed from Table Bay. They carried provisions for more than two years and a live cargo of which Anderson took a census on the day they left. Besides the bull, the two cows, and their calves presented by His Majesty, there were two stallions, two mares, three young bulls, three heifers, twenty goats, with an unspecified number of sheep and an assortment of pigs and poultry. Samwell and other uninformed members of the expedition may have been both surprised and aggrieved when they made off not in the direction of Tahiti but towards the south. Following his encounter with Captain Crozet on his previous visit to the Cape, Cook had resolved to examine the islands which had eluded him in his earlier exploration of the Antarctic. In case they became separated in those hazardous waters, he thought it prudent to give Clerke a copy of his instructions and appoint Queen Charlotte Sound their first rendezvous.13

EXPERIENCES IN THE NEXT PHASE OF THE VOYAGE, while they sought out the French discoveries to the south-east of the Cape, were by no means novel to veterans of the second expedition. Thanks, however, to the chart Crozet had supplied, the search was brief and rewarded by occasional glimpses of land. Within a few days of leaving port they met with violent gales which damaged the Resolution and proved fatal to some of its animals. Notwithstanding all their care, Cook lamented, the rolling of the ship, combined with increasing cold, killed several goats, especially the males, and a number of sheep. On 12 December, heralded by sportive porpoises and a seal, two islands appeared where they could discern neither trees nor shrubs and not many birds. Cook called the smaller Prince Edward Island, after the King’s fourth son, and the larger one, whose peaks were covered with snow, Marion Island after Aoutourou’s unfortunate benefactor; a larger group to the east he gratefully honoured with the name of Captain Crozet. Pushing farther on their south-easterly course towards the island found by Kerguelen, the two ships were for days at a time shrouded in fog and kept in touch only by the constant firing of guns. The bitter weather resulted in further casualties among the goats and, again through faulty caulking, the men of the Resolution suffered in leaky discomfort. On Christmas Eve they sighted what appeared to be lofty peaks enveloped in mist. Old Antarctic hands, who ‘had experienced many disappointments from the fallacious resemblance of ice islands to those of land’, remained sceptical.14

Land, nevertheless, it was — that which Kerguelen had supposed to be the projecting part of a southern continent. The ‘English’, wrote the self-effacing Cook, had since demonstrated that no such continent existed; as for the projection, it was an island of no great extent which because of its ‘stirility’ he called ‘the Island of Desolation’. The men who landed at points on the deeply serrated northern coast found no signs of trees or shrubs and only small patches of coarse grass which they gathered for the famished cattle. Streams ran down the bare hills in torrents, so they had no trouble in filling their water casks, while seals and sea lions provided oil for the ships and a change of diet for the less fastidious. Among the multitude of sea birds the penguins excited most interest. They lined the shore to watch the newcomers, standing upright in regular rows and looking, as Samwell observed, not unlike a regiment of soldiers. The poor creatures, he added, did not at first move out of the sailors’ way but grew more shy when great numbers were knocked on the head in wanton sport. One forager lighted on a memento left by the French discoverers, a bottle containing a document. This was inscribed with details of the present visit and replaced in the bottle which was then buried under a cairn of stones. Here Cook formally named his anchorage Christmas Harbour and raised the British flag — a ceremony the unpatriotic Anderson thought ‘perhaps fitter to excite laughter than indignation’. After a little further exploration by land and sea, Cook set off for New Zealand on 30 December. There had been more deaths among the animals (variously ascribed to cold, neglect, the sudden change of diet, or the penguin dung on the island grass), and it was imperative to seek milder weather and fresh fodder.15

Following an uncomfortable passage from Kerguelen Island, it was again the pressing needs of his ‘cattle’ that persuaded Cook to call at Van Diemen’s Land for a few days late in January 1777. The appointed rendezvous was Captain Furneaux’s Adventure Bay where they arrived on the 26th. Boats immediately put ashore from both ships and reported wood and water in plenty, though grass, which they needed above all else, seemed scarce. The next morning parties dispersed to collect supplies while some men went fishing in a brackish lake not far from the anchorage. In accounts of that enterprise Omai at length emerged from the obscurity which had enveloped him since he left the Cape of Good Hope. Lieutenant Gore mentioned him hooking or netting ‘several Goose Dishes’; rather more comprehensibly Samwell spoke of him as ‘by far the best fisherman’ — ‘he catched a great many more than any single person beside.’16

For the second time Omai had survived the rigours of sub-antarctic latitudes and would henceforth be the subject of comment not only among his companions on the Resolution but from voyagers less conveniently placed on the Discovery. Those assiduous journalizers, Burney and Bayly, again travelling together on the escort vessel, both made occasional mention of their old shipmate when he fell under their notice. Unfortunately Burney kept nothing like the informal narrative of his previous voyage, but his fellow officer John Rickman was the author of an unbuttoned record in which Omai was a conspicuous figure. Much of what Rickman wrote — and surreptitiously published — must be discounted if only because he could not have witnessed many of the incidents he related in circumstantial detail. However, when allowance is made for his tendency to invent and exaggerate, he adds, not always implausibly, to the evidence of more pedestrian writers.

At Van Diemen’s Land observers on both ships dwelt at length on the indigenous inhabitants who had eluded Furneaux and his crew in 1773. This time their distant fires had been seen from the outset, and on the 28th eight men and a boy, showing no signs of surprise or fear, emerged from the woods to greet a working party. They were dark in colour, carried no weapons except pointed sticks, and went completely naked. The next day a larger crowd assembled, including females of all ages who were as naked as the men unless for an animal’s skin which some wore to support their children. These primitive beings dwelt in rude shelters or hollow trees, subsisted mainly on shell-fish, and showed little interest in European tools and ornaments. As the more literate navigators seem to have recognized, they were face to face with living representatives of that philosophical abstraction, ‘natural’ man — a spectacle that was scarcely inspiring. Few people, Burney considered, might ‘more truly be said to be in a state of Nature’; and he went on to castigate the men who had so little sense of decency that, whether sitting, walking, or talking, they would pour forth their ‘Streams’ without any preparatory action or guidance. ‘The Inhabitants’, wrote the less censorious Clerke, ‘seem to have made the least progress towards any kind of Improvement since Dame Nature put them out of hand, of any People I have ever met with ….’ They lived in ‘the rudest State of Nature’, remarked Samwell, noting the men’s habit of idly ‘pulling or playing with the Prepuce’ as they stood before the outraged visitors. The erudite Anderson made similar observations which he used for the text of a discourse on the origins of modesty — whether implanted in mankind by nature or acquired from some person of uncommon delicacy. He ascribed the peacefulness of these ‘indians’ to their lack of possessions and thought their use of hollow trees for shelter authenticated the ancient legends of fauns and satyrs.17

One thing at least was certain: Omai belonged to an entirely distinct order of human kind. According to Samwell, he did not understand a word of the local tongue which was ‘quite different from that of the South Sea Islands.’ The same informant described how in fun — or possibly to deride the man’s nakedness — he threw a piece of white cloth, ‘cut in the Otaheite Fashion’, over the shoulders of ‘a little deform’d hump-backed fellow’ who ‘expressed great Joy by laughing shouting & jumping’. His conduct towards these unsophisticated aborigines was not always so graciously condescending. Most accounts of his first meeting with them say that, to their consternation, he fired his musket to show the superiority of European weapons to their pointed sticks. In another more doubtful version of the incident Rickman asserts that Omai, ‘though led by natural impulse to an inordinate desire for women’, was so disgusted by the females of Van Diemen’s Land that he fired into the air to frighten them away. Cook wrote little on such carnal topics, merely reporting from hearsay that the women rejected with great disdain addresses and large offers made by gentlemen on the Discovery (less fastidious, apparently, than Omai). His time was taken up in supervising shore duties and initiating his campaign to diversify southern resources. He considered freeing an assortment of his animals but, fearing the natives would destroy them, left only a boar and a sow which he took a mile or so into the woods in the hope they would be left there to breed and multiply. In addition, some unnamed benefactor — probably David Nelson — planted beans, potatoes, the stones of apricots and peaches. Cook made other short excursions into the interior but, less inquiring than usual or perhaps only pressed for time, he failed to test Furneaux’s theory that this country formed part of the northern mainland. The ships pulled out again on 30 January and after a fairly smooth passage in fine weather reached Queen Charlotte Sound on 12 February.18

Their stay of less than a fortnight in that familiar spot was overshadowed by memories of the affair in Grass Cove three years earlier. Omai was well to the fore when the Resolution came to anchor, waving a handkerchief to greet three or four canoes as he announced that ‘Toote’ had returned. At first the crews were shy about approaching at close quarters and few ventured on board. They were apprehensive, Cook supposed, that he had come to exact vengeance, and their fears were the more acute because Omai, whom they remembered on the Adventure, spoke openly of the massacre. Intent on reconciliation, Cook did everything in his power to reassure the anxious natives, with the result that they soon flocked to Ship Cove from all parts of the countryside. Among the early arrivals was a youth about seventeen years of age called Te Weherua (rendered as ‘Tiarooa’ by Cook), remembered for his friendliness and honesty during previous calls at the Sound. A more sinister visitor was a chief known as Kahourah, ‘very strong, & of a fierce Countenance tattowed after the Manner of the Country’, who was pointed out as a leader of the murdering band and the killer of Jack Rowe. Some of his countrymen urged the commander to slay this villain and were surprised when he refused, ‘for’, he acknowledged, ‘according] to their ideas of equity this ought to have been done.’ Had he followed the advice of these and other pretended friends, Cook remarked, he ‘might have extirpated the whole race’. The same note of mildly grim humour was repeated elsewhere in his account of the stay. The New Zealanders brought them three articles of commerce, he wrote, ‘Curiosities, Fish and Women’; ‘the two first’, he went on, ‘always came to a good market, which the latter did not: the Seamen had taken a kind of dislike to these people and were either unwilling or affraid to associate with them; it had a good effect as I never knew a man quit his station to go to their habitations.’19

Cook was forgiving but more vigilant than ever before. Mindful not only of the loss of his own compatriots but of the more appalling slaughter of Marion du Fresne and his men in 1772, he redoubled the usual precautions. A guard of ten marines was appointed to protect the encampment where, on the 13th, Mr. Bayly set up his observatory and sailors from both ships began their varied tasks — filling water casks, mending sails, brewing spruce beer, rendering down the blubber brought from Kerguelen Island. The same day, ‘to the great Astonishment of the New Zealanders’, as Samwell wrote, ‘Horses, Cattle, Sheep, Goats &c. with peacocks, Turkeys, Geese & Ducks’ poured out from the ‘second Noahs Ark’ to graze or disport themselves ashore. Surrounded by these domestic creatures, observed the same imaginative scribe, the visitors almost forgot they were ‘near the antipodes of old England among a rude & barbarous people.’ And even the natives seemed to shed some of their savage propensities when viewed at close quarters through Cook’s indulgent eyes. He praised the speed and skill shown by the men in building temporary huts in all parts of Ship Cove while the women busied themselves gathering provisions or dry sticks for fires to cook their victuals. As he watched their combined labours, he emptied his pockets of beads for which the old people and children scrambled in competition. This and similar acts of munificence were amply rewarded. He and his men received no little advantage from their neighbours, he remarked, and went on to acknowledge in particular almost daily tributes of fresh fish.20

In his earlier expectations that Europeans might one day profit from their own benevolent efforts, Cook was bitterly disappointed. Not a vestige remained of the gardens Mr. Bayly and his companions had established near the observatory, and there were no signs of animals or poultry. A search elsewhere in Ship Cove was, however, slightly more encouraging. Cook found cabbages, onions, leeks, etc., with a few potatoes, all overrun with weeds. The potatoes, originally brought from the Cape, had improved with the change of soil, he noted, and were highly esteemed by the natives. Yet they had not troubled to plant out a single one, much less any of the other vegetables. Nevertheless, on Samwell’s authority, the altruistic navigators cultivated the plots and sowed more seeds in the belief that they would be ‘of Service to the Country’. As for the livestock left during previous visits, unconfirmed rumours reached Cook that a hog and some poultry still survived in distant parts of the Sound. He had intended leaving sheep and cattle but now limited his gifts to a pair of goats, male and female, with a boar and sow which he bestowed, not very hopefully, on two importunate chiefs. A variation on the normal flow of commerce was the purchase, towards the end of the visit, of several New Zealand dogs, priced at a hatchet apiece. Finally, Cook bestowed on this barren land two animals which had not previously figured in records of the voyage: in the interests of posterity he released on Motuara Island a pair of rabbits.21

On many of his excursions Cook was joined by Omai not only as companion but, somewhat surprisingly, in the role of interpreter. For, though showing no linguistic aptitude on the previous voyage, he had with enhanced social status acquired the gift of tongues. The commander described him speaking to a ring of attentive New Zealanders and elsewhere asserted quite explicitly that he understood them ‘perfectly well’. Anderson did not go quite so far, merely stating that he followed their language ‘pretty well’ since it was ‘radically’ the same as his own, ‘though a different dialect’. The only dissentient voice was Rickman’s. In his view Omai knew less of what these natives said than many common sailors and was preferred to them only because he was Cook’s favourite. Proficient or not, he was the go-between when a large party, including both captains, visited Grass Cove to collect fodder and make inquiries at the scene of the affray. The inhabitants showed manifest signs of alarm when Cook arrived with his entourage, but he allayed their fears with a few presents and induced them to give an account of the fatal clash. It had occurred in the late afternoon while the men of the Adventure were eating their meal at a distance from the cutter, surrounded by natives. When some of the latter snatched bread and fish, a quarrel broke out which led to the shooting of two New Zealanders; but before the sailors could reload they were overwhelmed and killed. Another informant put the blame on Captain Furneaux’s black servant who had been left in charge of the boat and — so this story went — struck a man he caught stealing from it. On hearing the victim’s cries, those gathered round the other sailors had taken fright and begun the attack. What happened to the cutter could not be established: some said it had been burnt, others that it had been carried away by strangers. Whatever the precise facts of the whole affair, Cook was satisfied that ‘the thing was not premeditated’ and, further, that the clash had arisen from thefts committed by the natives and ‘too hastily resented’ by Rowe and his companions.22

These conclusions were of no comfort to anyone and did nothing to endear the New Zealanders to their visitors. The forthright Samwell roundly condemned them as ‘the most barbarous & vindictive race of Men on the face of the Globe’. Anderson expressed himself more temperately; indeed, in a lengthy survey of their customs he did justice not only to their artistic skill but to the humane feelings that coexisted with their cruelty. To remedy their horrid practice of destroying one another it would, he thought, be necessary to bring in plenty of animal food, but on a more extensive and certain plan than Captain Cook’s. Their present condition, he felt, was ‘little superior to that of the Brute creation’. ‘No Beast can be more ravenous or greedy than a New Zealander’, echoed Burney who attributed the natives’ troublesome conduct on this visit to the commander’s misguided clemency. In that opinion he was supported by Omai. Towards the end of their stay, Cook himself records, just as he and Omai were re-embarking after a visit ashore, the notorious Kahourah left the ship. More vengeful than his master, the officious young man urged Cook to shoot Rowe’s murderer and then proclaimed that he himself would be the executioner if the chief ever came back. Ignoring these threats, Kahourah appeared the next morning with his family and was taken to the captain’s cabin by Omai who ordered that the villain should meet his desserts. On his return soon afterwards, he saw that Kahourah was untouched and, as Cook relates, reproached him bitterly: ‘“why do not you kill him, you tell me if a man kills an other in England he is hanged for it, this Man has killed ten and yet you will not kill him, tho a great many of his countrymen desire it ….”’23

Following an independent line, as he did so often, Rickman took a favourable view of the place and gave qualified praise to its people. Of the expedition’s arrival he wrote, ‘Not a man on board who did not now think himself at home, so much like Great-Britain is the Island of New Zealand.’ And he included in his narrative the story of a youth on the Discovery who, ‘desperately in love’ with a local maiden and ‘charmed with the beauty of the country’, deserted with the intention of settling ashore and founding a dynasty. Such love was only found ‘in the region of romance’ he remarked of the touching affair which ended with the hero’s recapture and the relatively mild sentence of twelve lashes (incidents mentioned by no other annalist). But even this man of sensibility was compelled to acknowledge that love between visitors and denizens generally assumed less idyllic forms. Among the seamen, he wrote, the traffic with women was ‘carried to a shameless height’ and though the first price might be trifling — ‘nails, broken glass, beads, or other European trumpery’ — it ‘cost them dear in the end.’ Another offender he singled out was Omai ‘who, from natural inclination and the licentious habits of his country, felt no restraint’, indulging ‘his almost insatiable appetite with more than savage indecorum.’ If the same observer can be credited, whenever he could escape Cook’s watchful eye, Omai was hardly the paragon of discreet moderation Sandwich had conjured up: ‘he set no bounds to his excess, and would drink till he wallowed like a swine in his own filth.’ On such occasions he was surrounded by the common sailors who taunted him as he did ‘the poor Zealanders’. Yet, Rickman added with a touch of compassion:

He was indeed far from being ill-natured, vindictive, or morose, but he was sometimes sulky. He was naturally humble, but had grown proud by habit; and it so ill became him, that he was always glad when he could put it off, and would appear among the petty officers with his natural ease. This was the true character of Omai, who might be said, perhaps, by accident, to have been raised to the highest pitch of human happiness, only to suffer the opposite extreme by being again reduced to the lowest order of rational beings.24

Rickman is the most critical of several witnesses to one of the strangest episodes in this unhappy voyage. His newly acquired pride, combined with notions he had picked up from high-born English friends, persuaded Omai that he must now have retainers of his own. Even before reaching New Zealand, Cook explains, his charge had expressed the wish to carry one of its natives away with him. Now in the amiable Tiarooa he found a willing recruit. Once he elected to go, the youth took up his quarters on the Resolution and, thinking he would disappear once he had got all he could from Omai, Cook at first paid little attention. But when he stayed on it looked as if Omai had deceived the young New Zealander and his family by assuring them he would come back. ‘I therefore caused it to be made known to all of them’, Cook emphasized, ‘that if he went away with us he would never return’. The announcement made ‘no sort of impression’ and Tiarooa persisted in his determination. Since he was of chiefly rank (the son, it was said, of a tribal leader killed in a recent raid), another youth was chosen to go as his servant but was later removed from the ship. At the last moment a replacement was found in a boy of about nine or ten named Coaa (more properly Koa) who was enlisted in a manner Cook described: ‘he was presented to me by his own Father with far less indifference than he would have parted with his dog; the very little cloathing the boy had he took from him and left him as naked as he was born.’ The captain again tried to make the natives realize the improbability, or rather impossibility, of the boys’ return, but with no effect: ‘Not one, even their nearest relations seemed to trouble themselves about what became of them.’ He therefore consented to their going, the more willingly, he wrote, because he ‘was well satisfied the boys would not be losers by exchange of place’; and he went on to describe how the New Zealanders lived ‘under perpetual apprehinsions of being distroyed’ through unending tribal wars and their insistence on revenge.25

The incident obviously troubled Cook who, in Rickman’s view, was party to a transaction, the possibility of which he had formerly denied — the selling of their children by New Zealand parents. Omai paid two hatchets and a few nails for his two retainers, alleges Rickman, and Cook himself mentions Tiarooa’s mother coming on board the afternoon before they sailed to ‘receive her last present from Omai’. In whatever light the affair might have appeared to the New Zealanders, whether as the bartering of their own flesh and blood or the ceremonial exchange of courtesies between equals, all observers agreed that they displayed natural human feelings when finally parting with the boys. Their friends, noted Rickman, expressed their grief ‘very affectingly’, while Cook spoke of Tiarooa and his mother exhibiting ‘all the Marks of tender affection that might be expected between a Mother and her Son who were never to meet again.’ Not only did she weep aloud, wrote Samwell, but ‘cut her head with a Shark’s Tooth till the blood streamed down her Face.’26

In the initial phase of their new life the boys were closely watched by sympathetic witnesses of whom Samwell was the most eloquent. As the expedition left the Sound and the last canoes put back to shore, Tiarooa and Coaa wept but made no attempt to leave the ship. They remained in fairly good spirits until land began to disappear when, with the onset of seasickness, ‘they gave way to that grief which in spite of all their Resolution lay heavy at their Hearts’. They ‘cryed most piteously’ and ‘in a melancholy Cadence’ chanted a song in praise of their native land and its people — or so their audience interpreted it. The first night they lay on the bare deck, covered with their cloaks, and with the dawn of another day resumed their weeping and their mournful singing. Omai vainly tried to comfort his forlorn charges, while Cook, in an attempt to win them over, ordered them to be fitted out with jackets of the red cloth so prized by New Zealanders; but the boys took little notice of this finery. With Omai’s encouragement, Tiarooa might have become reconciled to his situation had it not been for Coaa who sat each day for hours weeping and repeating his plaintive song. On hearing it, the young chieftain would go and sit beside his servant to chant with him and ‘partake of his Grief’. They had not been at sea a week when an incident occurred recalling Omai’s similar experience on the Adventure. One day early in March the weather was calm enough for Captain Clerke and Lieutenant Burney to pay Captain Cook a visit. On their arrival, the panic-stricken boys fled from the deck to hide, fearing ‘some design on their lives, as in their country’, Rickman explained, ‘a consultation among the chiefs always precedes a determined murder.’ They continued in the same unhappy state for many days until, reported Cook:

their Sea sickness wore of[f], and the tumult of their minds began to subside, these fits of lamentation became less and less frequent and at length quite went of[f], so that their friends nor their Native country were no more thought of and [they] were as firmly attached to us as if they had been born amongst us.

Gradually they picked up English words and adopted English habits. At first they preferred fish to all other food, but later grew accustomed to shipboard diet and acquired a taste for wine, though, Samwell noted with approval, they never became ‘in the least intoxicated’.27

On recovering appetites and spirits, the New Zealanders were able to answer Cook’s numerous questions about their homeland. From Tiarooa he learned of the perpetual feuds among his people and of the existence (confirmed by the informant’s life-like drawings) of enormous snakes and lizards, the latter ‘Eight feet in length and as big round as a mans body’. These creatures sometimes seized and devoured men, tunnelled into the ground, and were killed by means of fires lit at the mouths of their burrows. Both boys spoke of a ship which had reached their country before the Endeavour (known to them as ‘Tupias Ship’). The captain had fathered a son, still living, by a New Zealand woman, and the crew, stated Tiarooa, had first introduced venereal disease. Cook derived whatever comfort he could from the last revelation and went on to say that the disorder was now ‘but too common’, though the natives did not find its effects ‘near so bad’ as on its first appearance; their remedy was ‘a kind of hot bath arrising from the Steam of green plants laid over hot stones’.28

The two boys did something to restore the reputation of their compatriots among members of the expedition. They were both ‘universally liked’ wrote David Samwell. When he overcame his homesickness, Coaa (or Cocoa, as the surgeon’s mate engagingly called him) proved to be of a ‘very humoursome & lively’ disposition and used to afford his shipmates ‘much Mirth with his drolleries’. Tiarooa was described more summarily as ‘a sedate sensible young Fellow’.29 Except for the ill-fated Ranginui, kidnapped by de Surville, they were the first New Zealanders in recorded history to leave their country. And all unknowingly they now followed the path of their forbears towards the ancestral Hawaiki.

COOK HAD LEFT QUEEN CHARLOTTE SOUND on 25 February and, with the aim of reaching the Arctic in the northern summer, pressed forward with an urgency that provoked muttered criticism from the lower decks. Contrary winds, however, impeded the north-easterly passage, added to which he again found himself in trouble with the live cargo. He had thought the hay and grass taken on at New Zealand would last until they reached Tahiti, but by the middle of March fodder was Running Out and he was forced to sacrifice some of the sheep in order to save more precious livestock. Visiting the Resolution on the 24th, Clerke and Burney found an ‘alarming’ situation on that vessel through the shortage of fresh supplies. Many animals had been killed and served to the ship’s company, others were reduced to ‘mere skeletons’, while the crew had been placed on a daily allowance of two quarts of water. The officers said nothing of Omai, but it seems not unlikely that his spirits were rising with increasing temperatures and remembered signs of his old environment. For Anderson’s benefit he had already identified a red-tailed bird ‘call’d Ta’wy by the natives of the Society isles’. On 27 March they entered the tropics and two days later sighted land, an island of no great size protected by a reef against which the surf broke ‘with great fury’.30

It was Mangaia, hitherto unknown to Europeans, the southernmost of the group which now bears Cook’s name. On the morning of the 30th warriors were seen gathered on the reef brandishing their weapons and uttering cries of defiance much in the manner of the New Zealanders. Viewing them through his spyglass, Anderson found them a tawny colour, most of them naked except for a sort of loin-cloth, though some wore a cloak thrown over the shoulders. Two men soon approached the Resolution in a small canoe, showing extreme signs of fear until Omai, who addressed them in his own language, reassured them to some extent. He was tactless enough to ask whether they ate human flesh — a charge that was indignantly denied — and they left after accepting a few presents. Later in the day the more commanding of the two was persuaded to come aboard and shown over the ship, Omai again acting as interpreter. Cook expressed disappointment that the man was not more surprised by the ‘Cattle’ and mentioned that on leaving the cabin he stumbled over a goat ‘and asked Omai what bird it was’. Barred from landing by the reef and heavy surf, the captain reluctantly left ‘this fine island’ which appeared capable of supplying all his wants. Its inhabitants seemed ‘both numerous and well fed’, the men ‘stout, active and well made’, in actions and language ‘nearer to the new Zealanders than the Otaheiteans’, in colour ‘between both’.31

They continued their northward course and in a couple of days reached the island of Atiu whose people closely resembled the Mangaians but seemed more friendly. Led by a chief carrying the symbol of peace, a coconut branch, men came aboard and were greeted by Omai who understood them ‘perfectly’, making the appropriate responses to the chief’s incantations. When taken over the ship, the visitors displayed gratifying wonder at the animals and returned with pigs, coconuts, and plantains, in return for which Omai generously gave them the prize they most coveted, a favourite dog he had brought from England. Since there was again no passage through the encircling reef and no safe anchorage, Cook decided to make an attempt to take on urgently needed fodder by boat. On 3 April a party set out and succeeded in reaching the island by transferring from their boats to native canoes which carried them over the reef. Lieutenant Gore was in charge, accompanied by Mr. Anderson, Lieutenant Burney, and Omai who went as interpreter and who, by all accounts, proved himself the hero of the occasion.32

Greeted by emissaries bearing green boughs, they were escorted through a great throng of people and presented to a succession of dignitaries, culminating in the principal chief or ‘Aree’ who entertained them, ‘much in the Stile of the Friendly Isles’, with ceremonial displays performed by young women and armed warriors. In return Omai delivered a speech and gave the Aree a bunch of red feathers. Then, ‘perhaps to shew his Gallantry, [he] took a Cocoa nut & drawing a very handsome Dirk which had been given him in England, broke it open and presented it to one of the Ladies.’ Both he and Gore explained their purpose in coming, but neither the chief nor his subjects paid much heed, intent as they were on satisfying their curiosity. As they pressed round the four men, the dense crowd (at least two thousand, Anderson estimated) examined their clothing and persons while displaying the same dexterous skill in theft as their Tahitian cousins. They continued to pester and pilfer the visitors for the rest of the day and firmly resisted any attempts at escape. Omai was greatly alarmed when he saw an earth oven being heated and, to his companions’ annoyance, asked the natives whether they were cannibals. He also wondered if they were preparing to kill the strangers and burn their bodies, as the Boraborans did, to conceal the crime. His fears were allayed when a pig was brought to the oven, and he eased the tension by taking a club and demonstrating how it was used in his own country — a performance that vastly entertained the audience. Cook’s report of the affair also made it clear that his favourite, with a lavish use of hyperbole, had taken every opportunity to emphasize British prestige and martial power:

Omai was asked a great many questions concerning us, our Ships, Country, &ca and according to his account the answers he gave were many of them not a little upon the marvellous as for instance he told them we had Ships as large as their island, that carried guns so large that several people might sit within them and that one of these guns was sufficient to distroy the whole island at one shot. This led them to ask what sort of guns we had, he said they were but small, yet with them we could with great ease distroy the island and every soul in it; they then desired to know by what means this was done, accordingly fire was put to a little powder, the sudden blast and report produced by so small a quantity astonished them and gave them terrible ideas of the effects of a large quantity, so that Omai was at once credited for every thing he told them.

Anderson gave Omai deserved praise for his resourcefulness, while Burney attributed their final release to his spectacular display. After feasting the guests with roast hog and plantains, towards nightfall the islanders informed them they could now leave. Stripped of their loose possessions, including Omai’s precious dirk, they were carried in canoes to their boats and made their way back to the ships.33

As he reflected on his experiences ashore, Anderson regretted that the brevity of the visit and the behaviour of the natives had frustrated an opportunity he had long wished for — ‘to see a people following the dictates of nature without being bias’d by education or corrupted by an intercourse with more polish’d nations, and to observe them at leisure ….’ He was inclined to think that in detaining his companions and himself they were impelled only by curiosity or the desire to steal what they coveted or perhaps by a combination of both motives. One event he recorded with special interest was Omai’s meeting with three of his countrymen living on Atiu. They were survivors from a canoe which had been driven from its course and eventually, after a harrowing voyage, carried to this island. When the incident happened was uncertain but it must have been at least twelve years earlier, for the men had not heard of Captain Wallis and knew nothing of the conquest of Raiatea by Opoony and the Boraborans. It was a ‘circumstance’, commented Anderson, ‘which may easily explain the method by which many of these places are peopled.’ In his account of that memorable day, Cook remarked that the castaways were now so satisfied with their situation that they refused Omai’s offer of a passage back to their native island. Slightly enlarging on Anderson, he too theorized on the implications of the affair. ‘This circumstance’, he wrote, ‘very well accounts for the manner the inhabited islands in this Sea have been at first peopled; especially those which lay remote from any Continent and from each other.’34

The episode at Atiu had yielded no supplies worth mentioning, so, rather than run further risks among these difficult people, Cook decided to continue the search elsewhere. He first made for the neighbouring islet of Takutea which was found to be without inhabitants, though there were signs of occasional visitors. Here two boat crews under Mr. Gore managed to negotiate the reef at great risk to themselves and collected coconuts and fodder, in return for which the scrupulous lieutenant deposited nails and a hatchet in one of the deserted huts. Omai, reported Anderson, ‘dress’d’ some of the spoils for dinner, the fruit of a plant ‘eaten by the natives of Otaheite in times of scarcity’; but the dish proved ‘very indifferent’. With the appetites of animals and men whetted rather than appeased by this perilous interlude, they next headed for the Hervey Islands, first charted during the previous voyage.35

When land came in sight on 6 April, to Cook’s surprise (for he had supposed the place uninhabited), canoes put out from the shore. The occupants, though they seemed darker than the people of Atiu, were clearly related and Omai again understood their speech. He persuaded them to come alongside and answered their numerous questions about the ship, its name, its captain, the size of its crew — ‘a bad thing’ he told Anderson, for in his country that meant they intended an attack. The surgeon himself spoke of their ‘disorderly and clamorous behaviour’ and mentioned their ‘fierce rugged aspect resembling almost in every respect the natives of New Zeeland’. Their conduct did indeed recall early European encounters with that barbarous nation. They refused to board the ships, attempted to kidnap Mr. Bayly’s servant, and stole anything they could lay their hands on. One particularly audacious theft was their seizure of a piece of beef which someone on the Discovery had enclosed in a net and placed in the water to ‘freshen’. They then took their prize to the Resolution and sold it or, according to another witness, restored it as a result of Omai’s threats. In their ‘Manners’, commented Midshipman John Watts, using the stock comparison, they were like ‘the New Zealanders, great Thieves & horrid Cheats’. It was in these circumstances that Omai’s boys reappeared after a prolonged eclipse. ‘Here’, wrote Samwell, ‘we found our New Zealand Ship mates as expert as any of us at trafficking, the younger boy Cocoa bought a fine Fish for a piece of brown paper he picked off the Deck & was highly delighted at having overreached the poor Indian.’ Their native propensities were again in evidence when two boats, after vainly searching for an anchorage, reported that the islanders, armed with pikes and clubs, had lined the reef as if to oppose a landing. ‘The two new Zealanders’, Samwell further commented, ‘express their Astonishment, that of the great number of people we have had in our power we have not yet killed any.’36

Less bloody-minded than Omai’s retainers, Cook was not prepared to risk men and ships in this inhospitable spot. Frustrated in the fourth successive attempt to obtain provisions and water (for the supplies taken on at Takutea were quite insufficient), he was compelled to take stock of the situation. He had been disappointed at every landfall since leaving New Zealand, he had been held back by unfavourable winds, and he now concluded it would be impossible to reach the Northern Hemisphere in time to carry out the intended exploration in the coming summer. Everything possible had thus to be done not only to preserve the animals but also to save stores so that the search for a northern passage could be made a year later than originally intended. Instead of continuing towards Tahiti, therefore, he redirected his course towards the Tongan Group whose lavish hospitality, twice enjoyed in the previous voyage, had earned them the name of the Friendly Isles.37

Such was the plight of the expedition that Cook decided to sail by night as well as by day, with the Discovery, the more navigable of the two ships, acting as pilot. When they approached land on 14 April, boats were immediately ordered ashore; ‘for now’, explained Cook, ‘we were under an absolute necessity of procuring from this island some food for the Cattle otherwise we must lose them.’ It was an uninhabited islet of the Palmerston atoll, already sighted in 1774, and although difficult of access, it supplied ‘a feast for the cattle’ in an abundance of scurvy grass and young coconut trees. The men also found ample provisions for themselves in the varied fish of the lagoon and the tropical birds, so tame they allowed themselves to be lifted from the trees. Now restored to his native element, Omai came into his own, winning praise on all sides. He settled ashore with his two young followers and in a very short time, acknowledged the grateful commander, caught with his scoop net enough fish to serve the whole party and in addition to supply the crews left on both ships. He showed his companions how to procure fresh water by digging in the sand and introduced them to a large eel which they found delicious eating, though so repulsive in appearance that without his guidance they would have shunned it. The well-read Anderson likened him to the Mosquito Indians used for a similar purpose by the buccaneers. His talents, however, went beyond those of a mere forager: assisted by the New Zealanders, he ‘dressed’ fish and birds ‘in an oven with heated stones after the fashion of his country with a dexterity and good will which did him great Credit.’ In short, as his old friend Burney testified, he was ‘a keen Sportsman an excellent Cook and never idle — without him we might have made a tolerable Shift, but with him we fared Sumptuously’. Omai himself was so delighted with the place that he often declared his intention of returning to live there and become ‘King’. Yet he could never, by sun or compass, point out in which direction it lay, observed Samwell, who was pretty sure he would not be so foolish as to make the attempt.38

Refreshed by three days spent on this and neighbouring islets, the navigators resumed their westward passage. They sailed past Niue, called Savage Island on the previous voyage because of the implacable hostility of its people, and after experiencing wet and sultry weather for the final week caught the first glimpse of the Tongan Group on 28 April. They touched at the small island of Mango and at the beginning of May came to rest in the Resolution’s former anchorage at Nomuka, relieved to find themselves, as Rickman expressed it, ‘in safety on a friendly coast’. ‘We forgot the dangers we had escaped,’ he went on, ‘and thought only of enjoying with double pleasure the sweets of these happy islands ….’39

THE TROPICAL SOUTH continued to inspire impressionable minds and imaginations. Viewing a Pacific island at close quarters for the first time, Samwell thought Nomuka realized ‘the poetical Descriptions of the Elysian Fields in ancient Writers’. In a more extended account Rickman, another newcomer, responded with all the enthusiasm of a Bougainville or a Banks. While still at sea he found its fragrance ‘inconceivably reviving’ and, on approaching the shore, was delighted by the prospect before him: the plantations with their intermixture of various blossoms, the trees of vivid green, the little rising hills, the verdant lawns, the rich low valleys. As the ships moored in the harbour, he admired the innumerable canoes, curiously constructed and filled with fruits from the plantations or articles of local manufacture — cloth of different fabrics, calabashes, bracelets and breastplates ornamented with vivid feathers, mantelets artfully and beautifully arranged. With growing intimacy, he found the people friendly, generous, hospitable, ready to oblige (though some, alas, were ‘villainously given to thieving’), while the chiefs did everything in their power to serve and honour the visitors. Under their direction, he noted, such was the quantity of hogs and fruit supplied that it exceeded the daily consumption on both ships. Nor did their attentions cease there. They conferred on Captains Cook and Clerke the richest offerings they could make, breastplates decorated with red feathers; they feasted them ‘like tropical kings’ on barbecued pigs and poultry and most delicious fruit; and they entertained the entire expedition with music, dancing, pantomime. The captains in their turn were not wanting in generosity, Rickman emphasized, for they loaded the chiefs with hatchets, knives, linen cloth, glass, and beads. ‘Who knows’, speculated the eager young officer, ‘but that the seeds of the liberal arts, that have now been sown by European navigators in these happy climes, may, a thousand years hence, be ripened into maturity ….’40

Accustomed to such experiences, Cook passed summarily over the welcoming functions but made special mention of a grass ‘plat’ in front of the principal chief’s doorway, used for wiping the feet — a mark of cleanliness he had not encountered in these seas before. Once the civilities were ended, working parties were sent to gather wood and water, the observatories were set up, and the ailing animals transported from the Resolution. Omai’s linguistic gifts, so conspicuously lacking on his previous visit to the group, were again employed for the benefit of his companions. He was of great use not only as an interpreter, reported Second Lieutenant King, but in fostering good relations with the natives, ‘for they pay him great attention & listen to the stories he tells them about Britannee, which doubtless tends to keep up our consequence, too apt to be lessen’d by the familiarity of our intercourse ….’ He accompanied the captains on their daily excursions and acted as go-between in the brisk trade that soon sprang up in local produce and curiosities. In return for some of the articles brought from England, he himself laid in a stock of the red feathers so abundant here, so rare and precious in his own islands. And, reverting to Polynesian custom, he began the practice of spending the nights ashore with the ‘Wife’ provided by his considerate hosts.41

Omai had scarcely settled in with his new friends when he acquired another influential patron in a man of commanding presence who came from Tongatapu with a retinue of followers. His name was Finau — Feenough in Cook’s rendering — and he was introduced as ‘King of all the friendly isles’. Though he had some doubts about the propriety of the title, Cook entertained the supposed monarch in his cabin and conferred on the royal person a gown of printed linen with lesser gifts. Feenough secured the return of a large axe stolen before his arrival but seemed powerless to curb his subjects’ continual pilfering. One of them, a minor chief, was detected carrying off an iron bolt hidden beneath his clothes. For this crime he received twelve lashes and was confined on the Resolution until ransomed with a hog — penalties that deterred his fellow chiefs but not their servants until Clerke hit upon the device of shaving the heads of all culprits. Otherwise things went amicably enough and, while Omai cultivated his latest protector, Cook supervised shore activities and, with invincible optimism, the planting of English fruits and vegetables. At the end of ten days, since he found they ‘had quite exhausted the island of all most every thing it produced’, he thought it time to move elsewhere. He first intended making for Tongatapu but Feenough persuaded him to visit instead the islands in the north-east. Since his arrival the live cargo had ‘amazingly recovered’—’from perfect skeletons, the horses and cows were grown plump, and as playful as young colts.’ Not every member of the expedition, however, had benefited from the visit to Nomuka. Before the ships weighed anchor on 14 May the sharp-eyed Lieutenant Burney noticed that the older of the two New Zealanders had ‘contracted the Venereal Distemper’; ‘so it is,’ wrote Mr. King, ‘that wherever we go, we spread an incurable distemper which nothing we can do can ever recompence.’42

44 Night dance by Tongan women, after John Webber

45 Night dance by Tongan men, after Webber

46 Omai in European dress: detail of 45

After a tedious and sometimes hazardous passage from Nomuka, on the 17th the ships reached the island of Lifuka for a stay which marked the idyllic climax of this visit, perhaps of the entire voyage. Escorted by Feenough and Omai, Cook went ashore the next morning to receive a ceremonial welcome more elaborate and more protracted than any he had experienced before. First of all two long lines of natives appeared bearing gifts — yams, breadfruit, plantains, coconuts, sugar-canes, pigs, fowls, turtles — which they placed in separate piles, one for Omai and the other, twice as large, for Cook. It far exceeded any present he had ever received from an ‘Indian Prince’, wrote the grateful commander. The guests, surrounded by thousands of spectators, were then diverted by athletic competitions: wrestling bouts in a style resembling that of ‘our Cornish men’; boxing matches between Amazonian women; duels among pairs of young men armed with clubs. In return for this virile entertainment, at Feenough’s special request, the marines from both ships carried out military exercises and fired volleys from their muskets. The islanders again responded with a dance performed by a troupe moving ‘as one man’ to the beat of drums. At nightfall the Europeans let off sky and water rockets with gratifying effects on the vast concourse. As Mr. King observed, Omai used the occasion to emphasize British power, pointing out how easy it was for his shipmates to destroy not only the earth but the water and the sky. Cook for his part noted with satisfaction that the fireworks pleased the natives beyond measure ‘and intirely turned the scale in our favour.’ The Tongans, nevertheless, had the last word in this contest of spectacles. By the light of burning torches they staged a succession of formal dances, including one by young women who carried out their movements with the precision of a European ballet. These performances, like other events in a memorable interlude, were beautifully commemorated by the artist John Webber and moved David Samwell to poetic speculation. Had the navigators ‘at last found the fortunate Isles where all those Blessings are contained that “fancy fabled in her Age of Gold”’? He was inclined to think so but felt compelled to condemn two evils that marred this earthly paradise, the ‘exorbitant Power of the Chiefs’ and their ‘barbarous Treatment of the common People’.43

The festival, spread over several days, made an auspicious beginning to an interlude marred rather less here than elsewhere by pilfering. Cook merely reported the loss of ‘a Tarpauling and some other things’ which were spirited away before the thieves could be apprehended. The Discovery suffered more severely with the disappearance of various iron objects and, even more annoying, the ship’s cats. On the 20th a man was caught purloining one of the animals and, to the consternation of Europeans and Tongans alike, he turned out to be an important chief. Consulted about what should be done, Omai recommended a sentence of a hundred lashes, sternly pointing out that the higher the rank the more reprehensible the crime. The less doctrinaire Clerke awarded a token punishment of one lash and freed the malefactor, an act of clemency which won the abject gratitude of his subjects and fellow chiefs. In this incident Rickman found further proof of their friendly and pacific disposition. ‘They seem to be’, he claimed, ‘the only people upon earth who, in principle and practice, are true christians.’ Irritated by petty thefts, the visitors remained blissfully unaware that their hosts were meditating plunder on a truly prodigious scale. In the midst of feasts and entertainments these kindly islanders were, according to their own traditions, plotting the slaughter of their guests and the seizure of the ships. Happily for European illusions and lives, the plans miscarried, and on 23 May Feenough, one of the leading conspirators, left for an island in the north to get red feathered caps for Cook and Omai to carry to Tahiti. He promised to be back in a few days and asked the commander to wait at Lifuka until he returned.44

Cook had already discharged his debt to posterity by sowing Indian corn, melons, pumpkins, etc. in the well-kept plantations and spent the next few days adding to his knowledge of Tongan customs. He watched as a mother operated with wooden probes on the eyes of a blind infant while another woman in the same house used a shark’s tooth to shave her child’s head. Since there was no sign of Feenough by the 26th and provisions were becoming scarce, he decided to seek fresh supplies elsewhere. The ships had not yet cleared the island when, at noon on the 27th, a large sailing canoe reached the anchorage with an imposing passenger, Polaho (Paulaho), who was introduced as ‘King of all the Isles’. This was the second of Feenough’s rivals to appear within a week, for at the close of the festivities there arrived a personage of ‘sullen and stupid gravity’ claiming to be ‘King’. But he refused to visit the Resolution and, following Feenough’s example, the commander ignored him. Polaho was a more formidable pretender. He did not hesitate to come aboard, bearing a present of two fat hogs, ‘though not so fat as himself,’ Cook jested, ‘for he was the most corperate plump fellow we had met with.’ The commander found him sedate and sensible and, for the present, was not disposed to inquire into the legality of the titles assumed by ‘all these great men’. It was otherwise with Omai ‘who’, again to cite Cook, ‘was a good deal chagrined at finding there was a greater man than his friend Feenough, or Omai as he was now called for they had from the first chang’d names.’ The jealous young man closely questioned the monarch in an attempt to dispose of his pretensions and refused to accompany him and Cook when they went ashore.45

Followed by Polaho in the royal canoe, the two ships finally got away at daybreak on the 29th, heading south to continue their locust-like progress through the islands. By this time, reported Mr. Bayly of the Discovery, the people of Lifuka had very few things to dispose of except their women. The commerce, he added, was highly advantageous to the local men who received payment at the rate of a hatchet or a shirt per night. That, however, was only ‘the Common run of trade’ — in some instances he had seen ‘two hatchets & a shirt or sheet given for a Nights lodging with a fine young Girl.’46

Though his ultimate objective was Tongatapu, Cook had arranged to meet Polaho at Nomuka whither he sailed by the route he had previously taken on his passage north. The weather was squally and the ships often in danger from submerged reefs and sand-banks; but such hazards, the commander acknowledged with resignation, were ‘the unavoidable Companions of the Man who goes on Discoveries.’ They again landed at Nomuka on 5 June to find the islanders harvesting their yams which were ‘in the greatest perfection’ and, acquired for pieces of iron, did something to replenish supplies. On inspecting his own gardens, Cook saw to his ‘Mortification’ that only the pineapples were flourishing; most of the other plants had been destroyed by ants. He suffered a further disappointment when Feenough at last turned up on the 6th with news that the spoils of his northern expedition had been lost at sea. Cook disbelieved the supposed monarch’s story and was fully convinced of his duplicity on Polaho’s arrival the next morning. When they met ashore, the two royal pretenders spoke to each other but to what effect no one could tell, for out of loyalty to his new patron, King alleged, Omai misinterpreted the conversation. Polaho certainly seemed the greater and when they went aboard to dine there could be no more doubt. In accordance with Tongan protocol, Feenough was not permitted to eat in the presence of a superior and withdrew from the cabin when the meal was served. His larger claims were thus unfounded, but he still exerted some authority and appointed two of his underlings to guide the ships to Tongatapu where they arrived on 10 June. Among the first callers was Otago, Cook’s major-domo during his first visit. Testimonies of friendship were exchanged, he reported, but the man’s name was not again mentioned.47 Otago had served his purpose and now gave way to more influential figures.

As this was meant to be their last anchorage before they left for Tahiti, a camp, trading-post, and observatory were set up under the protection of marines and the animals unloaded (to the astonishment, as usual, of the native audience). Omai now spent most of his time ashore and built a small house for his ‘Girl’ and himself near the encampment. Because he was always in the company of Captain Cook and other officers, Samwell noted, he was considered a chief of great consequence by the Tongans and, as such, highly respected. The New Zealanders were ‘pretty well understood’, wrote the same informant, and spent most of their time with the local people who were very fond of them and paid them much attention. After once dancing their war ‘Heivah’, the two boys were often called on to repeat the performance — ‘which they did & were much caressed & admired for it.’48

Several times during the visit the islanders entertained their guests with feasts, concerts, athletic contests, and ballets which, if less spectacular than those seen at Lifuka, continued to draw admiring comment from some members of the expedition. Cook was evidently becoming sated with such junketing and ventured to criticize ‘a sort of sameness’ in the ‘Circular dance’, though he admitted that uninformed outsiders would view English country dancing with similar prejudice. His own interests attracted him more strongly to other aspects of Tongan life, in particular its highly developed ritual and its baffling social structure. At the request of his hosts, he attended one of their ceremonies of mourning and, much against their will, took part in an elaborate festival of initiation — the inasi — where following the example of other celebrants (and of Mr. Banks on a famous occasion), he stripped to the waist. Omai was his companion at both functions and assisted him in his determined efforts to unravel the intricate relationships of Tongan royalty. Polaho, there seemed little doubt, was ‘King’, yet one of his venerable relatives, ‘Mariwaggy’ (Maealiuaki), was described as ‘the first man on the island’, while Polaho himself was seen to do obeisance to an unnamed woman of prodigious sacredness. Feenough was clearly of lower status but was found to be ‘a man of consequence and property’ — certainly endowed with sufficient authority to offer Omai the chieftainship of the island of Eua.49

Under the strain of his combined roles as interpreter, diplomat, go-between, and chief-presumptive, Omai apparently suffered a temporary lapse from decorum. In the course of a dispute, relates Samwell, ‘in a drunken fit’, alleges Burney, he struck the Corporal of Marines who returned the blow. Highly offended by this insult, he complained to Captain Cook, but when his protector refused him any redress, Omai announced his intention of staying behind in these islands. He then left the encampment, taking with him his New Zealand retainers. Happily the quarrel was soon settled. A messenger was sent after him and, on his return the next day, Samwell concludes, ‘matters were made up to his satisfaction, tho’ Captn Cook would not punish the Corporal as Omai had struck him while upon duty.’50