RESTORED AT LAST TO HIS NATIVE SPHERE, OMAI NOW BECAME THE CENTRAL figure in an extended performance, part social comedy, part social drama, of which his shipboard companions were the absorbed and sometimes self-conscious spectators. ‘Many in England envy’d us the sight of Omai’s return to his Countrymen’, wrote Second Lieutenant King who, supremely aware of his privileged role, supplied a circumstantial account of the episode. As they approached Tahiti, he observed, their charge became more and more the object of their attention, while with anxiety equal to their own he grew increasingly thoughtful. Even before reaching Vaitepiha Bay on the evening of 12 August, they waited impatiently for canoes to arrive and when at last one man boarded the Resolution, Omai clasped him by the hand with emotion to ply him with questions. The visitor showed no sympathy in return and hardly the least surprise at being spoken to in his own language by a stranger dressed differently from himself. Nor was there any ‘wild Demonstration of joy’ from another canoe bearing a chief and Omai’s brother-in-law. The voyager embraced his relative with ‘marks of strong feeling & great tenderness’ but was received ‘rather Coldly than cordially’ until he took the men below to confer on them gifts of the red feathers he had brought from the Friendly Isles. King was a disgusted witness of ‘the farce of flattery & vanity’ that followed. The chief, who had scarcely noticed him before, now began to caress Omai, asked him to exchange names in token of friendship, and sent ashore for a hog in return for the precious feathers. As for the brother-in-law, a person of ‘most forbidding countenance’ in King’s view, he shed his distant manner and stayed on the ship till morning.1

In conversation with his compatriots, Omai managed to pick up some news of local affairs. The first man aboard had spoken of a ship which reached the bay after Captain Cook’s previous visit, but he added such unlikely details that Omai doubted his word. The others, however, were able to verify and amplify the report. There were, they said, two ships which had come twice from a place called Rema. The first time the strangers had built a house and left behind four men — two priests, their servant, and another man. At the end of ten months the same ships had returned to take the settlers away, leaving the house and near it a cross to mark the grave of their commander who had died ashore. Furthermore, they concluded, the strangers had left behind animals much finer than those on the Resolution. When his shipmates heard the last particulars, King related, disappointment and vexation were visible on every countenance: ‘We saw that our Act of benevolence from its being too long deferrd, had lost its hour & its reward; We saw the loss of a season & an immence deal of trouble all thrown away to no purpose ….’ There this tantalizing intelligence had necessarily to rest for the present. Since there was no wind and the moon was up, they attempted to tow the two vessels in with the aid of their boats; but they had no success and were compelled to lie off the coast for the rest of the night.2

By morning, news of the rarities acquired in Tonga had spread ashore and, as they moved into the bay, the ships were surrounded by a multitude of canoes filled with hogs and fruit for barter. Above all else the Tahitians demanded red feathers in return for their produce, so that, as Cook jested, ‘not more … than might be got from a Tom tit would purch[ase] a hog of 40 or 50 pound weight’. They still set a high price on hatchets and knives, ‘but’, he noted, ‘Nails and beads, which formerly had so great a run at this island, they would not now so much as look at.’ Some favoured visitors were taken below and one chief, who was allowed to deck himself out in feathered finery, spent the rest of the day at the cabin windows displaying himself to his fellow islanders, ‘like some eastern Monarch adored by his Subjects’. Soon after they anchored, about nine o’clock, Omai was joined by his sister in a meeting that satisfied all the expectations of sentimental observers. Cook passed the scene over as ‘extreamly moving and better concieved than discribed’, but the less delicately reticent Samwell gave some details. He mentioned the young woman’s cries of distress when she arrived in a canoe laden with hogs, breadfruit, and other refreshments for her brother. She was so deeply affected, he said, that she seemed hardly able to bear an interview with one ‘whom she had been so long without seeing’. As she came on board weeping, Omai embraced her but, to hide his own tears, took her below whence she returned to thank Captain Cook and his officers for bringing her brother back in safety. She, too, received a quota of red feathers and so did ‘all who had art to profess friendship’, added the disapproving Mr. King.3

After initiating routine activities, Cook went ashore later in the morning with Omai and some of his officers to wander, observe, and question in his usual manner. Otoo and other friends were flourishing, he learned, but there had been two recent fatalities. The elusive Vehiatua of his last voyage, Mr. Banks’s ‘little olive liped boy’, was no more. He had succumbed to an illness (some said to intemperance) and been succeeded by a brother who was now visiting another part of his domain. Of far greater moment to the outside world, the ‘celebrated Oberea’ had died since the Resolution last touched at Tahiti in May 1774. Cook recorded the fact without comment, but the gentle Clerke wrote in elegiac strain: ‘I felt severely for the loss of this good old Lady, for she was a most benevolent Being, and a firm Friend to our cause.’ In the absence of the new Vehiatua, they paid their respects to a venerable man from Borabora known as Oro, after the supreme god of the islands, though Cook declared his real name was Etary (more accurately Etari). Despite his sinister origins, Omai treated the sage with reverence, gave him a tuft of red feathers, and was conversing with him ‘on indifferent matters’ when his attention was drawn to an old woman. She was his mother’s sister and behaved with becoming emotion — she fell at her nephew’s feet and ‘bedewed them plentifully with tears of joy’. Leaving Omai with his aunt and the crowd which had gathered round them, the commander walked on to inspect the house said to have been left by the mysterious strangers.4

The place was closely examined by Cook and his companions. It was built of timber specially brought for the purpose, since each plank was separately numbered. The walls were pierced by shuttered apertures that ventilated the house and would, if necessary, have served for the firing of muskets from within. There were two rooms, each about five or six yards square, the inner one still containing a bedstead, a table, stools, and some articles of European clothing which the Tahitians carefully preserved. They had also protected the house by erecting a large shed over it so that it had suffered no damage from sun or weather. At a little distance stood a cross bearing the inscription, ‘Christus Vincit Car[o]lus III imperat 1774’. A few neglected cabbages grew near the house and a vine ‘in a bad state’, the only remnant of a plantation which the islanders had trampled underfoot when they tasted the unripe grapes and decided they were poisonous. In addition, the strangers had left several animals, though, to Mr. King’s relief, they hardly compared in number or variety with those on the Resolution. There were neither sheep nor horses but only goats, some hogs much larger than the local breed, cats which had gone wild, dogs of various kinds, and a solitary bull, now living elsewhere on the island.5

Cook had difficulty in piecing together an account of the visitors, for most islanders, he complained, were quite unable ‘to remember, or note the time when past events happened; especially if the time exceeds ten, or twenty months.’ Indeed, the voluminous European records of the episode are themselves sometimes obscure or contradictory. As the Englishmen had already divined, the strangers were Spaniards from Peru. On three separate occasions (not two, as Omai’s informants told him), they had come to assert His Catholic Majesty’s rights in the Pacific and in consequence had increased the score of Polynesian voyagers and Polynesian victims. They first called at Tahiti late in 1772, so giving rise to the rumours Cook had picked up on his previous visit to Vaitepiha Bay. After staying a month, they had left with four native volunteers; of these one died when they reached Valparaiso and another at Lima. The remaining two, having lived about eighteen months in the Viceroy’s palace and received Christian baptism, returned with the second expedition. They reached home in November 1774, accompanied by two Franciscan friars, their servant, and a translator, supplied with a portable house to accommodate them. This time the Spaniards spent two months in Tahitian waters, leaving behind the tiny mission and the body of their dead commander who had been buried near the house. Once more native volunteers travelled to South America with the Spaniards, but reports differ as to their number. According to one version, there were again four, of whom two died, while a third remained in Peru and the fourth returned to Tahiti. Another source mentions two men but says nothing of their subsequent fate. The survivor or survivors went back with the final expedition which called briefly at Vaitepiha Bay in November 1775 and then sailed off with the four Spaniards, Tahiti’s first European settlers.6

Whatever the precise facts, it was certain that the whole protracted enterprise had done virtually nothing to change the Tahitians’ manner of life or wean them from their ancient beliefs. In the period they spent on the island — little short of a year — the Franciscans had not made a single convert. Even more discouraging, the two survivors of the first expedition had deserted the mission they were intended to serve, rejected Christianity, and returned to the faith and practices of their ancestors.7 The prospect that Omai, still in his pagan state, might succeed in reclaiming his benighted countrymen was on the face of it exceedingly remote.

On his return from the Spanish house, Cook found his protégé ‘holding forth to a large company’; and it was only with difficulty that the young man was able to detach himself from the curious throng to make his way back on board. That evening the commander held forth on his own account to the ship’s company assembled on the quarterdeck. He spoke of the long and perilous voyage before them, pointed out the need to conserve supplies, and suggested that they might forgo their usual ration of spirits until they reached colder northern latitudes. To his satisfaction, the gathering agreed to the proposal and Captain Clerke’s crew followed their example the next day. So it was that during their stay in the islands no more grog was served to the men, ‘except’, as Cook coyly remarked, ‘on Saturday nights when they had full allowance to drink to their feemale friends in England, lest amongst the pretty girls of Otaheite they should be wholy forgoten.’ It seems probable that distant wives and sweethearts were often lost sight of in the days and weeks that followed. The women, noted Mr. Bayly, were thought friendlier than on former voyages, a fact he put down to their great desire for red feathers. Many would ‘cohabit’ for nothing else, he added, and as soon as they obtained a small quantity vanished from sight.8

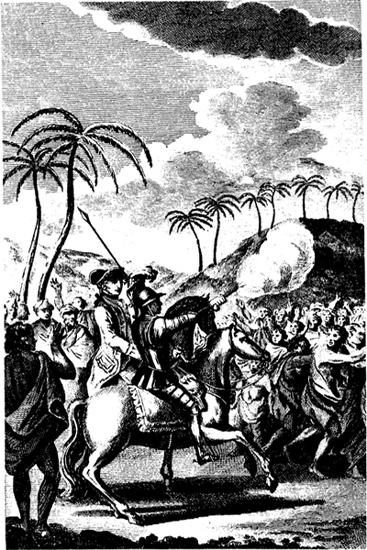

The self-denying resolution of his fellow travellers presumably had little effect on Omai. As a regular guest at the captain’s table he had ample opportunity to indulge in his newly acquired taste for wine; and in his role of returned voyager he would have had no trouble in satisfying other needs and appetites — with or without the expenditure of red feathers. For most of the time he was at Vaitepiha Bay, on the authority of Rickman, he spent the nights ashore, occupying the Spanish house and sleeping in a bed ‘put up after the English fashion’. He was so taken with the place that he ‘offer’d largely for it’, but the local people, fearing the Spaniards might return, would not part with the building. None the less they held him in high esteem not only because of his wealth and generosity but on account of his equestrian prowess. A couple of days after their arrival he and one of the officers exercised the two remaining horses amid scenes of ‘Uproar & confusion’ that Samwell found ‘impossible to describe’. Making a valiant attempt (and probably embroidering on fact), Rickman pictured him riding with the officer (Cook in this version), ‘dressed cap-a-pie in a suit of armour … mounted and caparisoned with his sword and pike, like St. George going to kill the dragon’, while, somewhat out of saintly character, he fired a pistol over the crowd whenever it became ‘clamorous, and troublesome’. The incident, as illustrated in Rickman’s published journal, added a highly imaginative item to the iconography of Omai.9

The heavy rain that fell for some days failed to deter visitors from swarming in from neighbouring districts to dispose of their produce and pay their respects to the two captains. Ereti journeyed from Hitiaa and became a familiar figure on the ships. Nearly a decade had passed since he first regaled Bougainville with a simple repast that recalled the golden age. Now the chief enjoyed dining on board in European fashion and, it was observed, ‘generally contrived to get drunk.’ Among feminine callers the most distinguished was the absent Vehiatua’s mother who allegedly ‘became captain Clerke’s taio, and exchanged names with him.’ Both sexes entertained their guests with formal dances which in Samwell’s opinion were far less graceful and diverting than those of the Friendly Islanders. The Oxford-educated Mr. King extended the comparison farther in a manner recalling the young Mr. Banks. The women here, he thought, were superior to their Tongan sisters — much more delicately formed, their features regular and beautiful, their outlines endowed with the softness and femininity so much wanting in Tonga. On the other hand he found the men in this island fell far short of his ideal in build, conduct, and manliness. ‘On the whole’, he summed up his impressions, ‘as to figure if we want’d a Model for an Apollo or a Bachus we must look for it at Otaheite, & shall find it to perfection, but if for a Hercules or an Ajax at the friendly Isles.’10

Fortunately the weather cleared on the morning of the 17th when Cook was invited to call on the Vehiatua who had returned to the bay. Perhaps through an excessive desire to impress the gathering, Omai showed none of the sartorial good taste so often praised in England. With the help of his friends, Cook related, he arrayed himself ‘not in English dress, nor in Otaheite, nor in Tongatabu nor in the dress of any Country upon earth, but in a strange medly of all he was possess’d of.’ Reaching the shore, they joined the revered Etary and then seated themselves before a large house, first spreading their presents before them. When the Vehiatua appeared with his mother and their entourage, he proved to be a boy about ten years of age, cutting ‘a very remarkable Figure’ in a gold-laced Spanish hat and scarlet Spanish breeches reaching to his ankles. After Omai and Etary had both spoken, an orator on the other side informed the commander that, though ‘the men of Rema’ had forbidden them to do so, the people of Vaitepiha Bay now welcomed him and placed their possessions at his disposal. The young chief embraced him, exchanged names to ratify their ‘treaty of Friendship’, and was so pleased by his gift of a sword and a rich linen gown that he paraded about to display them. Omai entrusted him with an elaborate feather maro or girdle he had fashioned on the passage from Tonga. Much against Cook’s advice and apparently to curry favour with both high chiefs, he asked the Vehiatua to dispatch the precious object to Otoo. When proceedings ended, the whole company adjourned to the Resolution for dinner. On the 19th the chief sent a handsome tribute of hogs, fruit, and cloth to Cook who responded that night with a display of fireworks as gratifying in its effects as earlier spectacles in Tonga.11

47 Equestrian exercise at Vaitepiha Bay

While addressing his men on the 13th, Cook had urged them not to be careless with their possessions and so put temptation in the way of the natives. Perhaps as a result of his warning, for the whole of their stay in this part of the island there were no complaints about theft and none of the customary ‘incidents’. The Tahitians allowed their inquisitive guests to wander wherever they would, even assisting Cook in his impious inspection of the dead Vehiatua’s remains hung round with mats and Spanish cloth. True, they showed great alarm at the removal of the memorial cross but were satisfied when it was replaced bearing an inscription to commemorate British exploits: ‘Georgius tertius Rex Annis 1767, 69, 73, 74 & 77.’ His Majesty’s loyal subjects were constantly reminded of their rivals, and both survivors of the first voyage to Peru appeared in person. One of them, who called on Clerke, ‘had imbibed a good deal of that distant, formal deportment of the Spaniard’ and ‘so larded his Conversation with si Signior’s as to render it unintelligible’. Nevertheless, the captain succeeded in drawing from him an opinion of ‘Lima’ which he thought a very poor country because ‘there were no red Feathers there.’ Further, ‘when he saw the great Abundance of Omai’s riches, he cursed the Signior’s very heartily & lamented much, that his good fortune had not given him a Trip to England instead of Lima.’ Though treated with great courtesy and rewarded with a present, the man did not come back. Cook had a similar experience with the second survivor who, on boarding the Resolution, was received with ‘uncommon civility’ but vanished before he could be questioned and failed to return. Cook suspected that during his own preoccupation with other matters the visitor had been hustled off the ship by Omai, ‘despleased there was a traveler upon the island besides himself.’12

The jealous young man was a source of much anxiety to his friends on the Resolution and had given them cause for concern even before they reached Tahiti. As that sympathetic chronicler James King set out the position:

… Captn Cook had taken a great deal of pains during the Voyage to prevail on Omai to agree to some certain arrangement by which his riches would be secur’d to him, & his own consequence rais’d & preserv’d, but he woud never listen to any plan, except that of destroying the bora bora chiefs & freeing his Native Island … from its present slavery to the King of that Island, & this C. Cook assur’d him he would not assist in doing, or even suffer him to do; not that he had any notion of its ever being in Omai’s power, to whom he was invariably preaching the little weight & trifling consequence he woud find himself to possess among his Countrymen. Omai was not the less obstinate & it answerd a bad end, in making him rather fear than love the Captn.

Since their arrival the worried captain had found no reason to modify his opinion or take a more hopeful view of his protégé’s future. With King he had been a witness of Omai’s reception by mercenary relatives and self-proclaimed friends who, it was evident, were in love not with the man but his possessions and who, had it not been for his red feathers, would not have given him a single coconut. He had not expected anything else, Cook confessed, but he had hoped that with the property he now owned — a fortune compared to which Lord Clive’s was ‘a mere Mite’, as another observer expressed it — Omai would have had the prudence to make himself ‘respected and even courted by the first persons in the island’. Instead, during their stay at Vaitepiha Bay he had ‘rejected the advice of those who wished him well and suffered himself to be duped by every designing knave.’13

At the end of ten days Cook decided to move on to his old anchorage at Matavai Bay where he hoped his troublesome charge might agree to settle. He had made the most of local resources — his reason for coming here in the first place — and Otoo clamoured for his presence. While the ships unmoored on the morning of 23 August, he and Omai went ashore to take leave of the Vehiatua. The visit was enlivened by the presence of another seer who, in the commander’s opinion, had ‘all the appearance of a man not in his right sences’. He was dressed only in plantain leaves wrapped round his waist and spoke ‘in a low squeaking Voice’ so that Cook found him almost incomprehensible, though Omai claimed to understand what he said. He advised the Vehiatua against leaving with the ships and foretold that they would not reach Matavai that day. The advice was unnecessary, objected the sceptical Cook, since no one had ever made such a proposal; as for the prophecy, he pointed out that there was not a breath of wind in any direction. Wondering at the credulity of his superstitious hosts, he bade them his last farewell and left with Omai.14

NO SOONER HAD THEY BOARDED THE SHIP than a breeze sprang up which carried the Resolution to Matavai Bay the same evening. But the Discovery did not arrive until the next day, so, as the fair-minded commander admitted, half the seer’s prophecy proved true after all. Back in this historic place, endowed in the English imagination with a supreme ruler, a royal family, a Court, and other appurtenances of the monarchical system, Cook lost no time in meeting Otoo who had hurried from Pare on the morning of the 24th and was waiting near the anchorage. When the two captains disembarked, no effort was spared to impress the ‘King’ and his subjects. Rickman, with his eye for the picturesque, describes the party landing from pinnaces, decked out with ‘silken streamers, embroidered ensigns, and other gorgeous decorations’, after which they moved in procession to the air of a military march played by ‘the whole band of music’. To the disappointment of the crowd, which had heard of his spectacular appearance at Vaitepiha Bay, Omai went on foot, dressed in uniform and almost indistinguishable from the English officers. On reaching the royal presence, Rickman continued, the returned traveller spoke in praise of the ‘Great King of Pretanne’, representing ‘the splendour of his court by the brilliancy of the stars in the firmament; the extent of his dominions, by the vast expanse of heaven; the greatness of his power, by the thunder that shakes the earth.’15

In a more prosaic and probably more accurate description of the ceremony, Cook portrays his charge arrayed in ‘his very best suit of clothes’, kneeling to embrace Otoo’s legs and generally acting with ‘a great deal of respect and Modesty’. Just as the commander had feared, the Vehiatua had kept Omai’s elaborate maro for himself, sending in its place a small tuft of feathers, not a twentieth part of its value. Now the suppliant tried to atone for his lapse by giving Otoo a large piece of gold cloth and more of the prized red feathers. None of the assembled dignitaries seemed to recognize him, and they paid him little attention — perhaps through envy, Cook surmised. He himself presented Otoo with a suit of fine linen, a gold-laced hat, some tools, and, most precious of all, feathers and a bonnet brought from the Friendly Isles. The monarch with his father, two brothers, and three sisters then left for the Resolution, followed by canoes laden with sufficient provisions to supply both ships for a week. Later in the morning Otoo’s mother came on board with her own gifts of food and cloth which she divided between Cook and Omai; for the royal family had now learned of the lowly Raiatean’s wealth and began to seek his friendship. Cook encouraged them to do so, he explained, because he hoped Omai would remain here and so be able to advise on the care and use of the remaining livestock. Moreover, it seemed that the farther he was from his native island the better he was likely to fare.16

Cook did not delay long before disposing of his precious cargo. After entertaining the guests at dinner, he took them back to Pare with a consignment of poultry — the peacock and hen he had received from Lord Bessborough, a turkey-cock and hen, a gander and three geese, a drake and four ducks. On reaching Otoo’s domain, he found the Spanish bull of which he had heard at Vaitepiha Bay. It was owned by Etary, he now learned, and was awaiting transportation to Borabora. He had rarely seen a finer beast, Cook remarked in envious admiration; his fellow captain, on the other hand, was moved to cynical jest: ‘poor Devil’, exclaimed Clerke, ‘he was the only Being I’ll answer for it, throughout the Isle, that cou’d not now & then solace himself with a little amorous dalliance’. In fact there was another involuntary celibate in Otoo’s keeping, a venerable gander, sole survivor of Captain Wallis’s parting gift to Oberea ten years before. The next morning Cook relieved the bull’s solitary plight by sending three cows to Pare. The rest of the livestock — a horse and mare, a young bull, some sheep and goats — he set ashore at Matavai. He now found himself relieved of a very heavy burden, Cook confessed; the trouble and vexation he had undergone during the voyage were hardly to be conceived. ‘But’, he comforted himself, ‘the satisfaction I felt in having been so fortunate as to fulfill His Majesty’s design in sending such usefull Animals to two worthy Nations sufficiently recompenced me for the many anxious hours I had on their account.’17

Other members of the expedition shared Cook’s relief that their troublesome passengers had at last departed. ‘Every person I am sure’, wrote Mr. King, ‘must have felt a singular pleasure in seeing them safely landed alive, after having been so long on board in such variety of climates ….’ His own feeling was that the animals would provide some small compensation for ‘the horrid disease’ the voyagers had brought to these islands. King had been put in charge of the shore station and the observatories set up on the site of Fort Venus with a guard of marines. Here the Discovery’s mainmast was repaired, the stores examined, and other preparations made for the long voyage that lay ahead. Nearby, on 26 August, Cook had a piece of ground cleared for yet another of his gardens. Chastened by earlier experiences, he had little hope that the Tahitians would look after this latest venture. Nevertheless, he sowed melons, potatoes, pineapples and, collaborating with David Nelson in a new horticultural experiment, planted out citrus or shaddock seedlings brought from the Friendly Isles. He was confident these would flourish unless they suffered the same fate as the Spanish grape-vines at Vaitepiha Bay. Omai, he noted, had salvaged slips from the damaged plantation and brought them with him to stock his own garden once he was settled.18

That issue was still to be determined, but in the meantime Cook was fully occupied as he supervised his men or greeted old friends or entertained his many visitors. Ereti, still avid for European hospitality, had followed the ships from Vaitepiha to babble of Bougainville; Oamo, consort of the lamented Oberea, came from distant Papara; and Odiddy, Cook’s companion on part of the previous voyage, lost no time in calling on his old patron. The Boraboran volunteer had been a great success on the Resolution and was much sought after at Tahiti when the ship returned there after parting with the Adventure. Indeed, in the course of a short stay at Matavai he married a young woman, the daughter of a local chief; and, according to George Forster, soon after the nuptials became the bedfellow of Oberea (like her near-contemporary Catherine of Russia, a connoisseur of youthful lovers almost to the end). Of even greater moment for his future, he had won the favour of Otoo and received from him a pressing invitation to remain at Tahiti. Though attracted by the offer, Odiddy decided he should first farewell his relatives in the Society Islands and accordingly sailed on with the Resolution. Cook had been tempted to carry his attractive protégé back to England but seeing no prospect of His Majesty’s ships ever returning (at this time he was, of course, unaware of Omai’s travels) he abandoned the idea. So in June 1774 the sorrowing youth was left at Raiatea, ‘universally belov’d by us all’, as one of his shipmates testified.19

48 Odiddy, Cook’s favourite, from a drawing by Hodges

Somehow in the intervening years Odiddy had found his way back to Tahiti and when the latest expedition arrived was living with his wife at Matavai under Otoo’s protection. In shipboard journals he was the subject of extensive comment, most of it uncomplimentary. Cook said surprisingly little about his favourite, merely recording that he had given him the clothes sent out by the Admiralty together with a chest of tools and ‘a few other articles’. King dismissed him as ‘a handsome looking young man’, ‘quite an Otaheite Coxcomb’, and ‘the most stupid foolish Youth I ever saw’. The last phrase was echoed in Samwell’s more elaborate account. They had been told by veterans of the last voyage, he observed, that Odiddy was ‘a fine sensible young fellow, much superior to Omai in every respect’. What, then, was their disappointment to find him ‘one of the most stupid Fellows on the Island, with a clumsy awkward Person and a remarkable heavy look’; further, when visiting the ship with his pretty wife, he was ‘almost constantly drunk with Kava’. As for his new clothes, after wearing them no longer than two or three days, he disposed of them to the seamen for hatchets and red feathers. In so doing, Samwell considered (lending support to the views of Rousseau), ‘he shewed some degree of Sense, as those articles would be of much more Service to him than English cloaths which are not half so well calculated for the Climate as their own’. His one champion was a German sailor on the Discovery, Heinrich Zimmermann, who thought Odiddy knew how to deport himself better than Otoo and spoke English as well as Omai, in spite of the latter’s two years’ sojourn in the country. ‘It would be more to the point’, his admirer asserted, ‘if he could come to Europe for a time, since he possesses much natural intelligence as well as a fine physique.’ William Bayly advanced a quite contrary opinion: ‘It does not appear that he would have made any figure in England if he had gone, for he appears to be one of the most silly fillowes Among thim.’20

Shipboard tattle, emanating from Bayly and Samwell, links most of the principal figures gathered at Matavai in a complicated plot worthy of contemporary English — or Tahitian — farce. Otoo is not implausibly said to have offered the services of his youngest sister to Cook for the duration of his stay, but, observing his inflexible rule, the commander declined the honour. He did, however, encourage a plan to marry the same ‘princess’ to Omai, now living ashore with his own sister and brother-in-law who had followed him from Vaitepiha Bay. The proposed alliance with the royal family would have enhanced his status, secured his safety, and kept him in Tahiti with the animals. Before the marriage could be arranged, alas, the prospective bridegroom fell into the clutches of the princess’s lover and his cronies. Conspiring to alienate their gullible victim from Otoo and seize his possessions, these ‘raskels’ ‘provided him with a very fine girl’, their accomplice, and one night descended on the couple as they slept. During the attack Omai fired his pistol, missing the chief assailant, and (to follow Bayly), ‘they all quarreled & the girl left him but not till she had in a manner strip’d him of his most valuable things, & to crown all she gave him the foul disease’. Bayly supplies a further twist to this tangled skein of intrigue by claiming that the unprincipled ‘girl’ was none other than Odiddy’s pretty young wife. If these sordid facts reached Cook, he failed to commit them to his journal. There he merely complained that the wilful young man rejected his advice, acted in such a way as to lose the friendship of Otoo and every other person of note, and consorted with ‘none but refugees and strangers whose sole Views were to plunder him’.21

49 A human sacrifice in Tahiti, after Webber

As the month of August drew to a close, the commander was beset by more urgent concerns than Omai’s amours and indiscretions. On the morning of the 27th he was told that two Spanish vessels had anchored in Vaitepiha Bay. The report was so convincing that he sent a junior officer, John Williamson, to spy on the potential enemy and at the same time ordered guns to be brought on deck and had the ships cleared for action. This martial display greatly alarmed the local populace who, Samwell surmised, still remembered the destruction inflicted by the Dolphin. Amid universal panic, trading came to a stop, canoes vanished, and ‘Sweethearts’ fled ashore. With Williamson’s return on the 29th, Cook learned that the story was a complete fabrication designed, he supposed, to lure him back to his first anchorage. Things had barely returned to normal when he discovered that the islanders, led by Otoo and his family, had again deserted the bay. He suspected that something had been stolen, and so it proved: a native guide had made off with four hatchets incautiously entrusted to him by one of the surgeons in quest of ‘curiosities’. Catching up with the fugitives, Cook allayed their fears, assured them he had no thought of punishment, and brought them back to Matavai. His extreme solicitude for the chief’s feelings is borne out by another incident not mentioned in his own journal. One night a man succeeded in evading the sentry and broke into the observatory. While he was moving about in the darkness, Mr. Bayly caught him by the hair but could not prevent his escape. The astronomer was convinced the thief was Otoo and told Cook whose only response was openly to absolve the royal marauder; the sentry, however, received ‘a smart flogging’ for his negligence.22

At this time Otoo himself was taken up with pressing affairs of state. During his previous visit to Tahiti (as William Watson testified), Cook had been deeply impressed by the great armada gathered to invade neighbouring Moorea. The attack had been unsuccessful, he was now informed, and since then sporadic fighting had continued between opposing factions on the two islands. On 30 August, hearing that his Moorean allies had been driven to the mountains, the chief summoned a council at his house where Cook happened to be visiting. In the course of a heated debate, the commander was asked to take part in a new expedition against the enemy but declined on the grounds that he knew nothing of the dispute and could not make war on people who had never offended him. Otoo also seemed lukewarm about the enterprise, for he spoke only a word or two throughout the whole conference. Nevertheless, he was irretrievably committed to the new campaign and a couple of days later received a summons to attend a second gathering. The great warrior Towha (or Tahua) was offering up a human sacrifice to ensure the success of the invading fleet which he would command. Thinking it a good opportunity to witness ‘this extraordinary and Barbarous custom’, Cook set out with Otoo for the sacrificial marae some distance to the west, accompanied by Anderson, Webber, and Omai. While the protracted ceremony went on, the little European party restrained their feelings, but after it was over they voiced their indignation in a stormy meeting with Towha, as Cook relates:

50 Omai with cook and other officers: detail of 49.

Omai was our spokesman and entered into our arguments with so much Spirit that he put the Cheif out of all manner of patience, especially when he was told that if he a Cheif in England had put a Man to death as he had done this he would be hanged for it; on this he balled out ‘Maeno maeno’ (Vile vile) and would not here a nother word; so that we left him with as great a contempt of our customs as we could possibly have of theirs.23

On their way back to the ships Cook and his companions spent the night of 3 September at Pare where they lodged in the ‘palace’ and attended a dramatic performance staged by the three princesses aided by a quartet of male comedians. From this point onwards the officers were caught up in a whirl of engagements so that, as one of their number remarked, ‘We wanted no coffee-houses to kill time; nor Ranelaghs or Vauxhalls for our evening entertainments.’ The day they returned to Matavai, Omai provided an excellent repast which included poultry and puddings besides fish and pork. Otoo graciously attended, while at this and later functions the host’s English friends used their best efforts to restore his damaged reputation and re-establish him in the eyes of influential islanders. Odiddy, too, was mindful of his social duties. Not unduly weighed down, it seems, by his own reputation as coxcomb and perhaps cuckold, he feasted his former patron and other English friends on those staples of Tahitian hospitality, fish, pork, and fruit. But Cook’s protégés could not compete with their high-born rivals. The royal family were tireless in their attentions and continued to heap on Cook and Clerke lavish presents of food and ‘prodigious’ quantities of fine cloth ingeniously arranged on the persons of comely mannequins. The two captains in their turn bestowed their own gifts, staged their dinnerparties, or contrived more spectacular diversions. A display of fireworks on Sunday the 7th was more dramatic in its effects than any of its predecessors. Most of the vast concourse were ‘terribly frightened’, wrote Cook, and when a table rocket exploded, ‘even the most resolute fled’. A week later he hit upon a further means of impressing the populace. After Omai had been thrown off a couple of times, the commander unkindly recorded, he and Captain Clerke rode the horses round the plain of Matavai, to the astonishment of the large train of spectators that followed. Henceforth the performance was repeated every day, and nothing, Cook felt, gave the Tahitians ‘a better idea of the greatness of other Nations’.24

While ink and attention were profusely expended on the assembled dignitaries, English and Tahitian, one of the Resolution’s company spared a kindly glance for Omai’s retainers. The New Zealand boys, wrote David Samwell, were delighted with the beauty of the island and spent much of their time on shore. The Tahitians treated them in a friendly manner, he said, though Coaa, the younger one, ‘had a few Battles with the Otaheite Boys & was generally worsted by stripplings less than himself, which convinced him at last that it would be best to live in peace with them.’ But he continued to bicker with the girls:

Cocoa being what we call an unlucky Dog was fond of playing his Tricks, which now & then would bring him into Squabbles with the Girls. One of these being plagued by him reproached him with his Countrymen eating human flesh, at the same time making signs of biting her own Arm, the poor boy was much hurt at it and fell a crying; but presently recovering out of his Confusion and being still insulted by her, he put his fingers to his head as if searching for a louse & made signs of eating it, at the same time telling her that if his Countrymen eat human flesh She eat lice which was almost as bad; by this quick stroke of retaliation our young Zealander got the laugh of his Side & the Girl was obliged to retreat & leave him master of the field.

Tiarooa, the older, quieter, and more dignified of the pair, was disposed of quite briefly: he ‘always lived upon good terms’ with the Tahitians and ‘was esteemed for his friendly & modest disposition.’25

Cook had failed to mention the two exiles since their first days on the Resolution and continued to ignore their existence — at least in the copious entries of his journal. He himself, as the month of September slipped by, was often at Pare in the company of Otoo who, it was noted, had shed his timidity in the commander’s presence and treated him with complete confidence. On the 16th the chief invited him to a function in honour of Etary, now settled near the palace after moving north from Vaitepiha Bay. Cook found the ceremony neither interesting nor curious but listened (presumably with Omai’s help) while the Moorean war was considered and Etary’s initial opposition overcome. The next evening news arrived that Towha and his fleet had already reached the island and launched an attack, with inconclusive results. On the morning of the 18th Cook set out once more for the royal seat, this time with Anderson, Omai, and the remaining sheep — an English ram and ewe, last survivors of King George’s gift, and three Cape ewes — which he had decided to present to Otoo. Further, he hoped that Etary, who claimed the Spanish bull, might be persuaded to leave it at Pare; but the godlike Boraboran, having first given his consent, later withdrew it. Following fruitless arguments, Cook finally issued strict orders that all the animals must remain in Otoo’s keeping until there was a stock of young ones to give away. His own account of the clash with Etary omits an incident recorded (evidently at second hand) in the lively pages of Samwell:

… Captain Cook finding there was nothing to be done with this stupid Block of Divinity by reasonable means, gave him to understand that all the Cattle must be the Property of Otoo, & then denounced Vengeance against him & all the people of Bolabola if any of them should ever offer to molest the Cattle or seperate them …. Omai was present at the transacting of this Business with the Eatooa, when Captn Cook happening to say that ‘instead of being a God he was the greatest Jackass he ever saw in his Life’, Omai with much Simplicity made answer ‘Ah Capt. Cook! he is a very goog Gog! a very goog gog Captn Cook!’26

His removal of the animals to Pare was the first sign that Cook was preparing to leave. He would gladly have stayed on in Tahiti, for it was unlikely, he said, that they would be better or more cheaply supplied elsewhere. Furthermore, the people were friendlier than ever before and since his arrival there had been scarcely a theft worth mentioning. Only one thing prevented his remaining longer in this agreeable spot — the problem of Omai. That much discussed figure continued to draw comment from his usually censorious companions. His real name was Parridero, asserted Mr. Williamson of the Resolution, and he called himself Omai only because, as in Ireland, ‘ye names of all the great Chiefs began wth an O.’ In one of his infrequent references to his old friend, Lieutenant Burney deplored his ‘Vanity’ and drew attention to the ‘tawdry’ nature of his attire. Even the genial Samwell complained that he acted ‘the part of a merry Andrew, parading about in ludicrous Masks & different Dresses’. But the main burden of criticism from these and other observers was on the score of his heedless extravagance and taste for low company. Such was his prodigality that to save him from destitution Cook felt compelled to impound most of his remaining possessions. As a result, he had nothing to trade with and was forced to beg for ship’s victuals in order to feed the household he had set up ashore. Much of his erratic behaviour was put down to the influence of his brother-in-law who by his conduct at both anchorages had acquired a sinister reputation as petty thief and parasite. Omai, alas, chose to associate with this and other ‘black guards’ rather than with members of the royal family and, scorning the advice of his well-wishers, was resolute in his determination not to settle in Tahiti.27

So there was nothing for it but to sail on and, as the Lords of the Admiralty had decreed, carry Omai to the island of his choice. By 20 September the overhaul of both ships was completed, supplies of fresh water taken on board, and the shore station dismantled; but for a number of reasons their departure was delayed more than a week. In the first place Cook was an absorbed spectator of the martial and political drama that continued to unfold. Early on the morning of the 21st Otoo arrived to announce that the war canoes of Matavai were assembling before they joined his own fleet and left to assist Towha in Moorea. Hoping to pick up some details of Tahitian naval tactics, Cook persuaded the chief to arrange a mock battle between two canoes, one commanded by Omai, the other by Otoo and carrying Mr. King and himself as observers. Following complicated manoeuvres and ‘a hundred Antick tricks’ on the part of the opposing warriors, the vessels clashed head on and, after a struggle between the two crews, Omai’s was judged the winner. Flushed with victory, the old campaigner was in reminiscent mood and spoke to Cook of adventures he had once related to Burney — of his capture by the Boraborans, his imprisonment on their island, and his escape by night on the very eve of execution. Finally, donning his suit of armour, he mounted a stage in one of the canoes to be paddled the length of the bay in full view of a disappointingly unresponsive crowd.28

Learning that Cook had decided to touch at Moorea on his way to the Society Islands, Otoo and his father called the next morning to ask whether they and their fleet might accompany him there. As long as he was not involved in the fighting, he saw no objection to the proposal and agreed to leave on the 24th. Before the plan could be carried out, however, news arrived that Towha had been compelled to arrange a truce with Maheine (or Mahine), leader of the opposing faction on Moorea, and had returned to Tahiti. In a further visit to Pare on the 23rd, Cook was present at a quarrelsome gathering where Otoo was blamed for the failure of the campaign through his dilatoriness in sending reinforcements and threatened with an attack by the forces of Towha and the young Vehiatua. Cook in his turn threatened retaliation if anyone dared to injure his friend, so putting a stop to all such violent talk. The debate had scarcely ended when a message came from Towha, who was not present on this occasion, summoning Otoo to a further conference to be held in his own territory. Cook was also invited but, feeling unwell, sent King in his place with Omai as interpreter. At this great assembly, attended by all the high chiefs including Oberea’s son Teriirere (known to King as Terry Derry), the leaders patched up their differences and made peace with Maheine. Omai not only carried out his duties faithfully but won the favour of Towha who in return for some red feathers gave him a double sailing canoe completely manned and ready for sea. It was a pity, thought his shipmates, that he was not staying here to enjoy the patronage and protection of this great ‘Admiral’.29

During the absence of King and Omai, Cook had reason to be grateful to his Tahitian friends. When they heard that he suffered acutely from ‘a sort of Rheumatick pain’, the princesses with their mother and their handmaidens visited the Resolution and subjected him to the same massaging and pummelling treatment Wallis had received from Oberea and her women. After three sessions under their practised hands, he found to his relief that he was completely cured. Nor were they less solicitous in attending to his material wants. On Otoo’s return from the conference with Towha, the whole royal family visited the ship to bestow on Cook such a lavish gift of provisions that, for want of preserving salt, he had to refuse some of the hogs. In gratitude for their services he did everything possible for his hosts. At Otoo’s request and following his specifications, he got the carpenters to construct a chest that would hold clothing and other European gifts. Not only was it fitted with locks and bolts but, as an additional safeguard against thieves, it was made large enough for two people to sleep on. The chief begged one last favour not mentioned by any diarist at the time but vividly recalled long afterwards by Midshipman John Watts of the Resolution. Having sat to Mr. Webber, Otoo asked if he might not have for himself a likeness of his friend and benefactor. Cook was pleased to comply, and the portrait, duly framed and placed in a box provided with lock and key, was handed to Otoo who promised to cherish the memento and show it to the commander of any ship that might visit the island.30

Everything was now ready for departure, but Cook lingered on for some days in this delectable place, detained, he said, by adverse winds. On the 27th he paid a visit to Pare to call on his friends and take a last look at the livestock. The whole collection, he found, was ‘in a promising way’. Soon after they were transferred from the Resolution, the cows had taken the bull and in due course could be expected to calve; the small flock of sheep was settling into its new home; and the offspring of goats left by English and Spanish visitors were so numerous that Cook felt justified in carrying off four from Otoo’s herd for distribution in other islands. The poultry also seemed in a flourishing condition: two geese and two ducks were already sitting and, though the peahen and the turkey had not yet begun to lay, there was no reason to suppose that they in their turn would not mate and multiply. In only one respect were the Englishmen disappointed. They had looked forward to witnessing the pleasure Oberea’s gander would have in again meeting his own kind; but the venerable bird had been too long alone. He kept aloof from his ‘brethren’, merely ‘making a Noise by himself’, as the kindly Mr. King recorded.31

Omai had been perfectly satisfied to leave the bulk of the animals here, realizing that Otoo would be in a better position than himself to defend them from possible marauders. As his stay on the island drew to an end, he began to act more prudently and follow his patron’s advice. The treasure brought from England was somewhat diminished, but he invested a portion of what was left in local cloth and coconut oil. These commodities were in great demand for trade and of finer quality than ‘at any of the other Society islands’, remarked Cook (extending the term to include Tahiti). Much of Omai’s erratic behaviour, in the commander’s opinion, had been due to the influence of his relatives and their shady hangers-on who had kept him to themselves with the sole aim of stripping him of all he possessed. By taking charge of what remained, Cook had frustrated their designs and now, to prevent further depredations, forbade Omai’s sister and brother-in-law to follow him, as they intended. On the 29th he set out for Moorea in his sailing canoe, gaily hung with flags and pennants of his own fashioning and manned by its Tahitian crew and the two New Zealanders. The boys, Rickman noted, ‘discovered no uneasiness at their present situation, nor any desire to return home.’32

The ships’ departure the same afternoon was a more ceremonial affair, graced by the presence of Otoo. The chief was as assiduous as ever in his attentions and only the day before had brought to the Resolution a carved canoe which he asked Cook to carry to ‘Pretane’ and present on his behalf to the high chief of that country. The commander had been compelled to refuse this bulky tribute but was pleased to see that Otoo realized to whom he was indebted for his most valuable presents. Now he requested that King George should send by the next ship red feathers and the birds that produced them, axes, half a dozen muskets with powder and shot — and the great chief was ‘by no means to forget horses’. Only one slight contretemps marred the proceedings. Otoo complained that Tahitian girls were being carried away and was disconcerted when they were bundled ashore; for, alleged Lieutenant Burney, he cared nothing for his subjects and merely wanted a handsome reward for allowing them to stay. Cook honoured him with a salute of seven guns and kept him on board until about five o’clock when he entered his canoe and left for Pare. After standing off the coast overnight, the ships followed Omai to Moorea.33

MEMBERS OF EARLIER EXPEDITIONS, notably Mr. Banks, had already landed on this island, lying less than ten miles from Tahiti, but Cook had not visited it before. His curiosity had doubtless been roused by its prominent part in the affairs of his Tahitian friends. Then, as always, he hoped to find here new subjects of interest and fresh sources of supply. Omai had arrived the previous night and when the ships appeared about midday on 30 September he was waiting in his canoe to guide them through the reef into the more westerly of two harbours on the northern coast. Cook thought it ‘a little extraordinary’ that no other visitor had mentioned their existence; indeed, he had always supposed Moorea to be devoid of such facilities. Now he found himself in a sheltered haven not inferior to any in the South Seas. Running inland for more than two miles, it was well provided with trees and fresh water, both easy of access, and was so placed that a ship could use the prevailing wind to sail readily either in or out. Thus it appeared to the professional sailor. Other more imaginative observers were impressed by the ‘romantic’ vistas, ‘delightful beyond description’, and by the background of volcanic mountains suggesting ‘the remains of some ancient & Noble Edifice’ or, alternatively, ‘old ruined castles or churches’.34 Such was the setting for the grim episode that followed.

51 The ships approaching Moorea; Omai’s sailing canoe maked A

As soon as they anchored, the ships were crowded with curious islanders for whom Europeans and their prodigious canoes were a complete novelty. They brought nothing with them to exchange but returned the next morning with breadfruit, coconuts, and a few hogs which they traded for hatchets, nails, and beads. Red feathers were not in great demand here and provisions seemed less plentiful than at Tahiti. It was also agreed by authorities on the subject that the women were far inferior to those they had just left. Even Cook, not much given to such comment, remarked on their low stature, dark complexion, and generally forbidding demeanour. In a day or two, however, the disappointed voyagers where cheered by the arrival of former sweethearts who, after their unwilling disembarkation at Matavai Bay, had found other means of reaching this island. Soon familiar routines were re-established. Some men went to gather firewood, found in great abundance in the nearby forest; some filled water-barrels from the crystal-clear streams; others took the few remaining animals ashore to graze in the lush, tall grass; and others again, departing from routine, constructed rough gangways designed to lure a plague of rats from ships to land.35

Cook was eager to make the acquaintance of the redoubtable Maheine who had withstood superior forces in the recent war, proving himself at least their equal. Not surprisingly the chief was less anxious to meet the friends of his Tahitian adversaries and waited a couple of days before making a cautious approach to the Resolution; and even then he had to be coaxed on board. This ‘Champion of Liberty’ was as great a disappointment to some diarists as Opoony had been to members of the first expedition. Expecting a ‘youthful Sprightly Active fellow’, they found a man between forty and fifty years old, most unprepossessing in appearance. He was scarred with the wounds of many battles, had lost one eye, and was, besides, bald-headed — in these islands a rare affliction which he tried to conceal by wearing a turban. He brought with him a wife (or ‘Mistress’, Cook suspected), claiming to be Oamo’s sister and therefore the sister-in-law of Oberea. Maheine gratefully accepted a flowered linen gown and some iron tools, professed his loyalty to Otoo, exchanged names with Cook, and at the end of half an hour left the ship. Soon he returned with his own gift of a hog and, after calling on Captain Clerke, departed with his consort (or paramour) for their home, some miles away.36

As the meagre journal entries indicate, little of note happened after this formal visit on 2 October. The same evening, Cook relates, he took a ride to the east accompanied by only a small ‘train’ of spectators, for Omai, his companion on the excursion, had forbidden the islanders to follow. After travelling some distance, they reached Maheine’s district, there to witness the devastation wrought by Towha and his warriors. All the trees were stripped of their fruit and not a house was standing — every one had been pulled down or burned. Perhaps out of consideration for the unfortunate chief, they forbore to repay his call and, returning to the ships, resumed their usual occupations. The following day, Samwell observed, Omai with the help of his own people was busy raising a deck over his sailing canoe. By the 6th Cook had decided to make for the livelier and more fruitful Society Islands and, with the intention of leaving the next morning, ordered the ships to anchor in the stream. But he cancelled his plans on learning that one of the goats put on shore to graze had been stolen. In a vindication of his actions written some time later he explained: ‘The loss of this Goat would have been nothing if it had not interfered with my views of Stocking other islands with these Animals but as it did it was necessary to get it again if possible.’37

Cook’s suspicions immediately fell on Maheine who, he disclosed, had asked him for two goats only the day before. He had been compelled to refuse but in the hope that Otoo might supply a pair he had sent the request on to Tahiti together with full payment in red feathers. Now he consulted two local elders who said they would call on the chief to retrieve the missing animal. Glad to take advantage of the offer, he sent them in a boat to deliver a threatening message to Maheine. The diplomats carried out their mission with complete success. On the evening of the 7th they reached the ships bearing not only the goat but the thief who claimed that he stole it because ‘Capt Cook’s men had taken his bread fruit & Cocoa-nuts, & refused to pay him for them’. There the affair might have ended but for another unfortunate loss. Just before the goat was restored, a second one, a highly prized female big with kid, disappeared from the flock which had again been grazing ashore. At first Cook supposed it had merely strayed into the woods, but he began to think otherwise when natives he sent to find the animal failed to reappear. The next morning his fears that he had again been robbed were fully confirmed. Most of the local people had moved away and Maheine, he learned, had fled to the southernmost part of the island.38

In the next stage of what was becoming a major incident, Cook first moved circumspectly. Once more following the old men’s advice, he sent a boat in charge of two midshipmen to the district where the goat was thought to have been carried. On the night of the 8th they returned empty-handed with reports that they had been treated with ill-concealed derision and fobbed off with empty promises. ‘I was now very sorry I had proceeded so far,’ Cook admitted, ‘as I could not retreat with any tolerable credet, and without giving incouragement to the people of the other islands we had yet to visit to rob us with impunity.’ In his perplexity he approached Omai and the two elders who told him to go with his men into the countryside and shoot every soul they met. This ‘bloody advice’ he could not follow, Cook commented, but he did resolve to lead an armed party across the island to reassert his damaged prestige and, if possible, reclaim the lost goat. With Omai and three or four of his people, thirty-five of his own men, and one of the elders to guide them, he set out at daybreak on the 9th.39

No sooner had they landed than the few remaining inhabitants fled in terror. When one man came within range, the zealous Omai, thinking his plan had been adopted, asked whether he should fire. Cook forbade him to do any such thing and, further, ordered him and their elderly guide to make it known that no one would be hurt, much less killed. The glad news soon spread, so that there were no more signs of fear and no opposition until the party reached the village suspected of harbouring the goat. Here armed warriors were seen to run into the woods and, on attempting to follow them, Omai was attacked with stones. At length Cook managed to pacify the villagers (by firing muskets over their heads, according to one report), but he could not get them to admit any knowledge of the stolen animal. Even his threats to their property, delivered through Omai, had no effect; whereupon he ordered some houses to be burned and several war canoes broken up. Once released, the flood of violence was not easily stemmed. For the rest of that day and most of the next Cook led his men through the island in an orgy of looting, burning, and destruction. On the evening of the 10th he had only just got back from a punitive foray into Maheine’s territory when he learned that during his absence the precious goat had been restored. The spoils of the expedition added a quantity of fresh provisions to the ships’ stores, but the person who profited most was Omai. He was as active as anyone in the rampage, noted Samwell, and returned with two more canoes and enough timber to build a European-style house.40

52 A view of Moorea, after James Cleveley

53 A view of Huahine, after webber

The episode released a spate of comment, ranging from bewildered post-mortem to downright condemnation. ‘I doubt not but Captn Cook had good reasons for carrying His punishment of these people to so great a length, but what his reasons were are yet a secret’, wrote Mr. Williamson, one of the officers directly involved. Except for Omai, ‘who was very officious in this business’, everyone carried out orders with the greatest reluctance, reported another eyewitness, George Gilbert of the Resolution. He could not, he confessed, account for Captain Cook’s actions — ‘they were so very different from his conduct in like cases in former voyages’. The loyal Clerke, while deploring the damage inflicted on ‘these good people’, said what he could on his colleague’s behalf. Every ‘gentle method’ was used to recover the goats, he claimed, but nothing availed in the face of a ‘perverseness’ which he ascribed to the workings of the Devil. Samwell assigned responsibility more directly to the chiefs who had ‘nobody but themselves to blame’; and he pointed out on the credit side that ‘during the whole of this disagreeable Business’ not one native had been hurt. But for the scrupulous Mr. King there seemed no reason for the captain’s ‘precipitate proceedings’ and nothing to be said in mitigation. He doubted whether punishing so many innocent people for the crimes of a few could be reconciled to any principle of justice and took a gloomy view of the consequences. These and other islanders, he thought, would give a decided preference to the Spaniards and in future might ‘fear, but never love us.’41

Cook himself seems to have felt some twinges of conscience as he reviewed the events of those few agitated days. Closing his journal entry for 10 October, he wrote: ‘Thus this troublesome, and rather unfortunate affair ended, which could not be more regreted on the part of the Natives than it was on mine.’ By the next day, he observed with relief, they were ‘all good friends’ again — the people were bringing their produce to barter ‘with the same confidence as at first.’ Evidently, however, there were none of the customary displays of sorrow when the ships set out the same morning, led by Omai in his sailing canoe. During the passage to Huahine the vanguard narrowly escaped misadventure. Before daylight the Englishmen heard firing which they supposed was Omai celebrating the first glimpse of land. Instead, they later discovered, his craft had nearly overturned in a squall and the shots were meant as a signal of distress. Somehow disaster was averted and, on reaching Fare Harbour at noon on the 12th, they found the canoe safely moored. Another incident in the crossing, recorded by King, concerned a native passenger who was caught stealing just before the Resolution entered the harbour. Cook ‘in a Passion’ immediately ordered the thief’s head to be shaved and his ears cut off, but ‘an officer’ (doubtless King himself) delayed the more drastic part of the operation until the commander’s anger had cooled. Minus his hair and the lobe of one ear, the man was then cast off the ship and made to swim ashore. While he failed to mention this affair, Cook noted with satisfaction that other passengers were telling the local people of his stern measures in Moorea, exaggerating the destruction at least tenfold. His hope was that such reports would improve the behaviour of these notoriously unruly islanders.42

AFTER AN ABSENCE OF MORE THAN FOUR YEARS, Omai had thus encircled the earth and returned to his starting-point. On reaching Fare, Cook found he had not yet landed but remained in his sailing canoe, surrounded by a crowd of whom he seemed to take little notice. At this juncture, confronted as he was by the urgent problem of his future, perhaps he was in no mood for exchanging social pleasantries. The question of finding a home for himself and his growing circle of dependants was still undecided, though the choice had narrowed to one between Huahine and Raiatea. In Tahiti the god-chief Etary had promised that his father’s land would be restored to him, and he now seemed to favour settling in his native island. Nor was Cook opposed to the idea, thinking his own influence there was sufficient to ensure that Etary’s undertaking would be honoured. On the afternoon of their arrival Omai boarded the Resolution with three or four others, ‘men of little consequence’ judged Bayly who happened to be present. He had come, it soon became evident, not to seek advice but to announce that he and his companions were going to attack the Boraborans living on Raiatea and wanted Cook’s help. He went on to say that, since his parents were both dead and he had no property in Huahine, he could not stay here. Cook flatly refused to have any part in the invasion, explaining that Orio and other Boraborans were his friends. He then offered to reconcile Omai with them, but the ardent young man was ‘too great a Patriot’ to listen to any such proposal. So without more ado — and contrary to his instructions — the commander took the decision into his own hands. ‘Huaheine’, he resolved, ‘was therefore the island to leave him at and no other.’43

While he was at Tahiti, Cook had already learned of political changes in Huahine. He had always supposed the principal chief to be Oree, but that venerable figure, it appeared, was only acting as regent for the youthful Teriitaria and, having been overthrown since the previous voyage, was now living in exile at Raiatea. His two sons were still on this island, however, and even before the ship anchored, hastened to greet their father’s friend. The next day Cook got ready to pay his respects to the young chief whose name he rendered as Tareederria. He hoped to take advantage of the presence of other leaders, attracted from all parts of the island by his arrival, to discuss arrangements for Omai’s future. That unpredictable person, Cook observed, dressed himself very properly for the meeting, prepared a number of handsome presents, and altogether, now he was clear of the ‘gang’ which had surrounded him in Tahiti, was behaving with such prudence as to win him respect. Followed by most of the ship’s company, the two disembarked and made their way to a large house where the gathering was to be held. There was some delay before Tareederria appeared with his mother — he ‘a very mean looking Boy’ about the same age as the Vehiatua, she ‘a fine jolly Dame … formerly a Tio of Mr Banks’s’.44

As befitted the importance of the occasion, proceedings were conducted with great formality. Omai, standing with a friend apart from the rest of the company, first offered tributes to the gods which were placed before a priest to the accompaniment of what seemed to Cook speeches or prayers. These invocations apparently praised King George, Lord Sandwich, the two captains (Toote and Tate), and gave thanks for the voyager’s safe return. The priest next took each object in the order in which it had been presented and, uttering incantations of his own, sent it off to a distant marae. The religious part of the ceremony was now at an end and Omai joined Cook who exchanged gifts with the boy chief and got down to business. Having warned his audience not to permit the abominable crime of theft, he pointed out with Omai’s assistance that their countryman had been well treated in England and sent back with many articles that would be very useful here. Were they prepared, then, to give or sell him a piece of land where he could build a house for his servants and himself? The alternative, Cook rather disingenuously suggested, was to carry him on to Raiatea. This last proposal seemed to please the chiefs, rather to the commander’s surprise until he discovered that Omai was saying he would go there and with the help of his European friends drive out the Boraborans. Cook soon quashed the scheme, again insisting that he would not countenance any such expedition. Thereupon, as he relates,

54 A view of Fare Harbour, Huahine, after J. Cleveley

a Man rose up and told me that the whole island of Huaheine and every thing in it was mine and therefore I might give what part I pleased of it to Omai. Omai, who like the rest of his Country men seldom sees things beyond the present moment, was greatly pleased with this declaration, thinking no doubt that I should be very liberal and give him enough; but it was by far too general for me; and [I] therefore desired they would not only point out the place, but the quantity of land he was to have. On this some Chiefs who had left the assembly were sent for, and after a short consultation amongst themselves my request was granted by general consent and the ground immediately pointed out, adjoining to the house in which we were assembled.

55 The ships’ carpenters building Omai’s house: detail of 54

Finally, in return for fifteen axes, some beads, and ‘other Triffles’, Omai was granted an area extending some two hundred yards along the shore and a little farther towards the hills.45

With this transaction completed, Cook was able to make plans for his stay on the island. He established a trading-station on shore, set up the observatories, and put the carpenters of both ships to work building a house from the timber pillaged in Moorea. By this means he hoped Omai would be able to safeguard his possessions and, to add further to his resources, the solicitous commander employed other hands to lay out a garden with shaddocks brought from Tonga and a variety of European fruits and vegetables. The landed proprietor himself was soon busy on the hillside at the back of his estate planting a small vineyard with the slips salvaged at Vaitepiha Bay. He was beginning to attend seriously to his affairs, Cook noted, and now repented his prodigality in Tahiti. A brother and a married sister were living here, but they did not plunder him as his other relatives had done. Nevertheless, they were powerless to protect either his person or his property, so, fearing he would be robbed when the ships left, Cook advised him to distribute some of his ‘Moveables’ among the principal chiefs and in this way secure their favour and support. Omai adopted the suggestion which Cook followed up with threats that he would return and visit the full weight of his resentment on any who might injure his friend during his absence.46

Little occurred to disturb the harmony between visitors and hosts in the week or so that followed. Perhaps as a result of the warnings issued at the assembly of chiefs, only one theft was reported and the punishment was such as to dissuade others from following the criminal’s example: half his head and one eyebrow were shaved and in addition he received a sound flogging. Cook was again indisposed but soon recovered sufficiently to accompany Omai on riding excursions when, asserted Samwell (surely in hyperbolical vein), ‘they were followed by Thousands of Indians running & shouting like mad People.’ Meanwhile normal tasks went forward and efforts were made to deal with another plague — not rats this time but cockroaches which devoured food, books, labels, stuffed birds, and soiled the bread with their excrement. For ‘delicate feeders’ put off ship’s victuals by these pestilential creatures, there was an abundance of breadfruit and other fresh provisions readily purchased for ironware and red feathers, as highly prized here as in Tahiti. The precious commodities soon attracted local girls who flocked aboard to reinforce the contingent carried from Moorea. Rickman describes cosy shipboard ménages where ‘the misses catered and cooked for their mates’. And to amplify the picture there is Bayly with his census of the sick — three or four men afflicted with yellow jaundice and twelve victims of ‘the foul disease’.47

In the customary manner the islanders diverted their European friends with entertainments and on the night of 22 October arranged ‘a grand Heivah’ held by candlelight in a large house. The players were Raiateans, led by a young woman ‘as beautiful as Venus’. Surfeited with such experiences perhaps, Cook did not attend but later in the evening interrupted proceedings to demand the return of a sextant which had just disappeared from Mr. Bayly’s observatory. At first the assembled chiefs were too absorbed in the performance to pay him much attention. Whereupon he stopped the players and promised that if the instrument was not found he would punish this island more severely than he had Moorea. As a result, the thief was pointed out sitting unconcernedly in the audience. Omai, who acted throughout as Cook’s interpreter and right-hand man, immediately drew his sword and arrested the felon, a native of Borabora as it proved. Carried to the Resolution, he was put in irons and, under Omai’s insistent questioning, told his captors where he had hidden the sextant. A search that night was unsuccessful, but it was discovered the next morning hidden in some long grass, quite undamaged. Meanwhile, alarmed by Cook’s threats, the chiefs had fled from the neighbourhood and were coaxed back only by assurances that neither their persons nor their property would be harmed. Then, as Mr. King reported, ‘we once more liv’d on amicable & agreeable terms.’48

The incident, however, had by no means ended. As the thief appeared to be ‘a hardened Scounderal’, Cook explained, ‘I punished him with greater severity than I had ever done any one before’. He omitted details but they were supplied by other chroniclers. With hair shaved and both ears cut off, the man was put ashore in a bleeding condition and, says Rickman, ‘exposed, as a spectacle to intimidate the people’. The sight inspired horror and disgust among the islanders, asserted the same informant, and even Omai was affected, though he tried to justify the commander’s actions by saying that in Britain the thief would have been killed. The miscreant himself was certainly not intimidated. A couple of nights later, probably helped by accomplices, he uprooted plants and vines from the newly formed garden and openly threatened to kill Omai and burn his house once the visitors had left. Cook again acted vigorously. He had the man seized and imprisoned on the Resolution, with the intention, he said, of carrying him elsewhere or, as others alleged, of marooning him on a desert island. But after a few nights on board the indomitable captive managed to free himself from his shackles, leaving members of the watch to bear the full brunt of their commander’s displeasure. The petty officers were disrated and on three successive days the sentry received a dozen lashes. A handsome reward of twenty hatchets was offered for the prisoner’s return but proved of no avail. He remained at large, a threat to Omai’s person and his future.49

By this time the carpenters had completed their work and the wooden house was ready for occupation. According to Zimmermann, the ungrateful Omai was dissatisfied with the result, saying that King George had promised him a building with two storeys and this had only one; moreover, he complained, it was a place ‘such as was used for housing pigs in England.’ Whatever its limitations, it was a solid edifice, eight yards long, six yards wide, and ten feet high, constructed with the smallest possible number of nails to lessen the danger of its being dismantled for the sake of the iron. And if it lacked a piano nobile, there was a loft above the main room and a magazine beneath. Omai furnished it with a bed and a few other articles, reported Samwell, and whenever he went out, unless Tiarooa was left in charge, was careful to lock the door and carry the key on his person. With the help of the local chiefs and his own men, his intention was to erect over the new house a large native building not only to protect it from the weather but to provide accommodation for his still growing ‘family’. Besides the New Zealand boys there was the crew picked up in Tahiti, one of his brothers, and a few other followers, some ten persons in all — ‘without ever a woman among them,’ Cook remarked, ‘nor did Omai seem attall desposed to take unto himself a Wife.’50