MORE THAN TWO YEARS PASSED BEFORE WORD OF OMAI’S REPATRIATION reached his English friends. And then it was overshadowed by more sombre tidings: ‘what is uppermost in our mind allways must come out first,’ wrote Sandwich to Banks on 10 January 1780, ‘poor captain Cooke is no more, he was massacred with four of his people by the Natives of an Island where he had been treated if possible with more hospitality than at Otaheite.’ The melancholy news, he explained, came from Captain Clerke who, writing from Kamchatka, reported an otherwise prosperous voyage: they had lost only two men from sickness and one by drowning. ‘Omai’, the First Lord went on, ‘arrived safe & was left at Huaheine but no particulars of his reception in Captain Cookes short letter which comes by the same conveyance.’ Cook did, however, give some details of the animals he had landed at Tahiti and the Society Islands — a horse and mare, a bull and several cows, a ram and seven ewes. Sandwich ended by mentioning the changes which had followed Cook’s death. Captain Clerke had taken over the Resolution and Captain Gore the Discovery. Clerke, now in charge of the expedition, would make one more effort to find a northern passage but did ‘not seem to have much hopes of success.’ The pessimistic forecast proved well founded. Like Cook before him, Clerke failed to penetrate through the polar ice to the Atlantic and did not long survive the attempt. He died in August 1779 and was buried in Kamchatka. Gore succeeded to the command of the Resolution while King was appointed to the Discovery. After taking a circuitous route to avoid the American colonists and their European allies (for Britain was again openly at war with its traditional enemies), the two ships anchored at Deptford early in October 1780.1

The interval since the Resolution set out from Plymouth in July 1776 had been an eventful one in the affairs of Omai’s two English patrons. After the brief eclipse that followed his withdrawal from Cook’s second expedition, Banks was again in the ascendant, both as private citizen and public figure. Seeking ampler space for his ever-growing collections, he moved from New Burlington Street in the autumn of 1776 to the roomy mansion in Soho Square that was to be his town house and the centre of his scientific activities for the rest of his life. Some two years later, in December 1778, he succeeded Sir John Pringle as President of the Royal Society, a position he was to occupy for the next four decades; and in the same memorable month, sponsored by Sir Joshua Reynolds and Dr. Johnson, he joined the select company of the Literary Club. His marriage to an heiress, Miss Dorothea Hugessen, in March of the following year ended his bachelor state but did little to alter the ordered routine into which he had settled. The bride, ‘a comely and modest Young Lady’, as Sir John Cullum described her, joined Banks and his sister in a harmonious ménage à trois which, contrary to all probability, endured until Sarah Sophia’s death in 1818.2

In marked contrast with his younger friend, Sandwich was nearing the end of his long career and was beset by misfortunes, both personal and public. In the month following Banks’s marriage he lost the woman who had been his companion for the past two decades and the mother of his second family. One evening early in April 1779, when she was leaving Covent Garden Opera House to return to the Admiralty, Martha Ray was shot and killed by an obscure clergyman, James Hackman. The assassin, who had met her at Hinchingbrooke some years earlier, ‘had been nourishing a hopeless passion for his victim’ and intended to commit suicide but failed in the attempt and was later hanged. Sandwich was prostrated by Miss Ray’s death and, though shunning society, could not ignore his pressing official duties. The blow fell while he was bearing the full brunt of criticism for repeated naval reverses in the unpopular war. By the time the Resolution and the Discovery reached the Thames, the danger of invasion was not entirely over and the divided country was on the brink of an election.3

With the expedition’s arrival, the First Lord was faced by urgent, if relatively minor, problems and again turned to his friend. Writing from the Admiralty on 10 October 1780, he brought Banks up to date with recent events: according to that gentleman’s desires, his gardener (David Nelson) had now been discharged from the ship; he himself with Captain King and Mr. Webber, the artist, had the previous Sunday visited Windsor where the drawings and charts of the voyage seemed to give His Majesty great satisfaction. The drawings were indeed very numerous, ‘near 200 in number’ and ‘exceedingly curious & well executed’, observed Sandwich, so he would like to consult Banks how to preserve them and select those that were suited for reproduction. ‘I allso wish to have your opinion’, he continued, ‘about the Journals which are now in my possession, which I think should be made publick with as little delay as the nature of the business will allow; but I had so much trouble about the publication of the two last voyages, that I am counting or rather unwilling to take upon me to decide in what manner & for whose emolument the work shall be undertaken ….’ Banks’s advice on the matter would be of great use, Sandwich concluded, and he hoped it would not be long before he had the pleasure of seeing his friend in town.4

As a result of his consultations and profiting from past experience, the First Lord found a solution in a collective compromise. King, the best educated and most cultivated officer of the expedition, was appointed co-author with the dead Cook. Banks acted as consultant throughout and Sandwich undertook the same office which he continued to perform even after March 1782 when his old opponent Admiral Keppel replaced him at the Admiralty. As the work progressed, a number of other people were called in to advise and comment. Members of the Burney family were asked to express their views on the esoteric subject of Polynesian music (asserting in the course of a complicated correspondence: ‘Omai had a very bad ear, & could never any where have been a musician’). The astronomer William Wales was also a contributor and so was Henry Roberts of the Resolution and so, among others, was Admiral John Forbes who composed the closing tribute to the late commander. In the matter of emoluments, it was finally decided that half the profits should go to Cook’s widow and family, a quarter to King, with smaller shares to the heirs of Clerke and Anderson (another casualty of the voyage), and to the Resolution’s master, William Bligh, presumably for the use of his charts.5

Someone was obviously needed to co-ordinate the whole enterprise. Sandwich’s choice fell on Canon Douglas who had already displayed his tact and proved his literary talent in revising Cook’s narrative of the second expedition and preparing it for the press. In the present instance Douglas was in effect the unacknowledged general editor, performing duties similar to those previously undertaken by the lamented Hawkes-worth. He skilfully combined Cook’s copious but incomplete records with the journals of his fellow travellers. He imposed some unity on the several contributions by rephrasing them in his own elegant Augustan idiom. And, while taking fewer such liberties than Hawkesworth, he reshaped his materials to emphasize dramatic incidents in the story or to focus attention on its leading figures. The annals of this epic contained no Banks to supply light relief for the heroic and now martyred Cook. Nor was there an Oberea to divert the public with her antics and her amours. But one personage could act both as foil to the commander and centre of exotic attention. ‘The history of Omai’, remarked this exceptionally candid editor, ‘will, perhaps, interest a very numerous class of readers, more than any other occurrence of a voyage, the objects of which do not, in general, promise much entertainment.’6

Following this cue, Douglas introduced into the narrative full details of Omai’s actions from the time of his embarkation at Sheerness until he arrived at Huahine. The account usually kept fairly close to the records of the voyage which were suitably emended or in some cases expanded. At the climax, however, as the ships were on the point of leaving the island, Douglas evidently thought some more elaborate passage was called for. Hence he placed in Cook’s mouth a long rhetorical set-piece for which there was little authority in his original journal (though there were unmistakable echoes from King’s). The commander is shown soliloquizing as he prepares to farewell his charge. ‘It was no small satisfaction to reflect, that we had brought him safe back to the very spot from which he was taken’, the passage opens. ‘And, yet, such is the strange nature of human affairs, that it is probable we left him in a less desirable situation, than he was in before his connexion with us.’ For, through being much ‘caressed’ in England, Omai had lost sight of his original condition and forgotten the extreme difficulty he must experience in winning acceptance from his countrymen. Had he made proper use of the wealth and knowledge acquired during his travels, he could have formed the most profitable alliances. But with childish inattention he had neglected this obvious means of advancing his interests. There followed a catalogue of his repeated errors and indiscretions in the Friendly Islands and Tahiti. Then Cook-Douglas pondered on Omai’s possible destiny:

Whether the remains of his European wealth, which, after all his improvident waste, was still considerable, will be more prudently administered by him, or whether the steps I took, as already explained, to insure him protection in Huaheine, shall have proved effectual, must be left to the decision of future navigators of this Ocean; with whom it cannot but be a principal object of curiosity to trace the future fortunes of our traveller.7

And so in the course of time it came about. Throughout the closing years of the eighteenth century a succession of navigators visited the group, leaving accounts not only of Omai’s fate but of developments in a critical period of Pacific history. Much of what they learned from their informants was of necessity obscure or contradictory. More than a decade elapsed between the Resolution’s departure and the arrival of further visitors. During his last voyage, while trying to clear up the mystery of the Spanish settlers, Cook (in his own person) had expressed the conviction that most islanders were unable to recollect past events or tell when they happened, even after an interval of only ten or twenty months.8 At a distance of ten years memories had inevitably grown dim, chronology become confused, many facts vanished beyond the possibility of recall.

THE FIRST EPISODE was indirectly linked with Banks who had grown in authority with the years, to become a kind of public oracle on a variety of topics. As early as 1779, on the strength of observations made during the voyage of the Endeavour, he had recommended to a parliamentary committee the establishment of a penal colony at Botany Bay. Nothing came of the proposal at the time but in due course, with the loss of the American possessions in the recent war, the scheme was revived. Sir Joseph Banks, as he was now known (he had been created a baronet in 1781), took an active part in organizing the expedition which set out in 1787 to found the settlement of New South Wales. One of the transports, the Lady Penrhyn, having discharged its human cargo on the inhospitable shores of the new colony, set out on the return voyage after a stay of only seven days. When it left Botany Bay the crew were already showing signs of scurvy and, as conditions worsened in the following weeks, Captain Sever, the commander, decided to make for Tahiti and procure fresh provisions. This course of action was probably influenced by the fact that the second in command, Lieutenant John Watts, had been one of the Resolution’s midshipmen on its last voyage. Almost eleven years after his previous visit, he again entered Matavai Bay on 10 July 1788.9

The Tahitians were as friendly as ever. They flocked round the Lady Penrhyn while she anchored, shouting “‘Tayo Tayo”’ or ‘“Pahi no Tutti,” Cook’s ship’, and soon opened a brisk trade in foodstuffs which they disposed of ‘on very moderate terms’. A chief who came on board that evening immediately recognized Watts and brought him up to date with local affairs. Otoo was still alive but at the time was absent from the district and would not be back for some days. He was now called ‘Earee Tutti’ and had, it seemed, suffered for his namesake’s actions. One night, in retaliation for Cook’s destructive rampage through Moorea, Maheine had landed at Pare, destroying all Otoo’s animals and forcing him to take refuge in the mountains. Towha, it was also suggested, had taken a hand in the business, and Watts remembered that chief threatening something of the kind in a quarrel with Otoo during his last visit to the island. The lieutenant picked up more news when Odiddy turned up the next morning. Cook’s favourite rejoiced at seeing Englishmen again, made affectionate inquiries about his friends, and took much pleasure in recalling his travels on the Resolution. Since he was ignorant of Cook’s death, Sever decided not to enlighten him and indeed gave him a present supposedly sent by the commander. Odiddy also mentioned the raid on Otoo and spoke briefly of Omai and the New Zealand boys. They had been dead ‘a considerable time’; they had died through sickness; there was only one horse left on Huahine. Beyond that Watts could discover nothing.10

Early on the morning of the 14th the officers were summoned ashore to pay their respects to Otoo. They found him surrounded by ‘an amazing concourse’ and were pleased to see that he still possessed Webber’s portrait of Cook, quite undamaged in its wooden box. It went with him everywhere, they were told, and was certainly placed in his canoe when he set out for the Lady Penrhyn. Watts thought the ‘king’ improved in person and much the best-made man they had seen. He was always accompanied by a woman of great authority but by no means handsome who seemed to be his wife. During his visit to the ship Otoo asked after his friends, Cook in particular, and on going below was astonished to find how few crewmen there were and what a number were sick. He in turn spoke of the revenge taken by his enemies from Moorea, asked why the Lady Penrhyn had not brought cattle, and added one or two details to the account Odiddy had given of Omai’s end. After the event, he told Watts, there had been a skirmish between the people of Huahine and warriors from Raiatea. The invaders were victorious and carried off a great part of the dead man’s property.11

They heard no more of Omai during the rest of the visit. Their situation in a small ship with a disabled crew seemed so precarious that Watts spent little time ashore and then was careful not to wander far. He did learn, however, that since his last visit great numbers of people had been carried off by venereal disease and that many women, especially in the lowest class, suffered from the ‘terrible disorder’. Other signs of European influence were few. Apart from goats and cats, there seemed to be no imported animals and for want of attention Cook’s vegetable gardens had gone to ruin. The islanders occasionally brought pumpkins, peppers, or cabbage leaves with their own produce, but they themselves refused to eat the pumpkins and said the peppers poisoned them. Except for the blade of one table-knife, they had used up all their iron and were so anxious to acquire fresh supplies that they sold their own commodities at very reasonable rates. Though the once prized red feathers were now worthless, hatchets, knives, nails, and similar objects were as much in demand as ever. One article of barter was of particular interest to Watts. It was a large ring which he immediately recognized as belonging to one of Bougainville’s anchors — that very anchor which Cook had bought from Opoony in 1777 (and of which Omai had spoken in his talks with James Burney four years earlier). By some means the relic had come into the hands of Otoo who agreed to part with it for three hatchets.12

Otoo was assiduous in his attentions. He visited the ship daily and often acted as an intermediary in trade — not without profit to himself the visitors noted. He urged them to attack his enemies on Moorea, but to this suggestion they gave a positive refusal. Instead, after a fortnight in the bay, they set sail for the Society Islands. Their invalids had made a most astonishing recovery and, as they reflected with satisfaction, during the whole of their stay not one musket had been fired. Nevertheless, Captain Sever was careful not to announce his intentions and got under way before daylight. Despite these precautions, the Lady Penrhyn was soon boarded by a crowd of Tahitians led by Otoo who remained on the ship until it cleared the reef. He expressed great sorrow at their sudden departure, complained of the time which had elapsed since the British last visited the island, and urged them not to stay away so long again. He asked them to bring back some animals, especially horses, and finally requested that a few guns should be fired — a compliment Captain Sever was obliging enough to pay him. A pathetic note was introduced into the farewell by the presence of Odiddy. He, too, had visited the ship every day, always with a gift of ready-dressed provisions. Apparently things had not gone well with him in Tahiti, for he said he was very unhappy and begged to be taken to Raiatea. But Otoo forbade him to leave and Captain Sever was forced to put him into his canoe, shedding tears in abundance. Not once as the exile made for the shore did he look back at the Lady Penrhyn, now bound for Huahine.13

They sighted the island on 25 July but contrary winds prevented them from reaching Fare until the 29th, and then Captain Sever merely lay to off the coast. He intended staying only a day or two and did not think it worth the trouble to enter the harbour. The natives were again very friendly, swarming round the ship in their canoes while they offered the newcomers fresh produce and urged them to anchor inside. Sever resisted their importunities and as a result neither he nor his companions seem to have gone ashore. Fortunately, on the evening of their arrival they were visited by a local chief able and willing to answer their inquiries. He was an elderly man who went by the name of ‘Tutti’, and Lieutenant Watts remembered having often seen him in the company of Captain Cook. He confirmed earlier reports that Omai and the two boys were dead and spoke briefly of their life together. Cook’s fears on his protégé’s behalf were apparently quite justified. After he was settled, Tutti informed Mr. Watts, Omai was forced to purchase for himself and his family large quantities of cloth and other necessaries. Taking advantage of the situation, his neighbours made him pay extravagantly for every article. In addition, he often visited Raiatea and never went empty-handed. So by these means he expended much of his English treasure during his lifetime. The old chief assured Watts that Omai had died in his own house, as had the New Zealand boys, but in what order he was unable to say.14

Of the sequel Tutti was more positive. Warriors came over from Raiatea to seize the remnants of Omai’s property which, they claimed, belonged to them by right since the dead man was a native of their island. The invaders carried away many articles but destroyed the muskets on the spot, breaking the stocks and burying the gunpowder in the sand. The fighting had been very fierce, Tutti added: great numbers were slain on both sides, and peace was not yet restored. Watts himself saw three men who had been terribly injured and learned (probably from Tutti) a few more facts about Omai’s possessions. His house was standing but had been taken over by the high chief of Huahine and was now covered by a very large one ‘built after the country fashion’. As for his horses, soon after foaling the mare had died together with the foal. The stallion was still living, ‘though of no benefit’; ‘thus’, Watts concluded, ‘were rendered fruitless the benevolent intentions of his Majesty, and all the pains and trouble Captain Cook had been at in preserving the cattle, during a tedious passage to the islands.’15

BENEVOLENT INTENTIONS again had some part in bringing the next British ship to Tahiti. Only three months after the Lady Penrhyn’s departure, a second naval vessel entered Matavai Bay, sent out to gather seedlings of the breadfruit tree and transfer them to the West Indies. In the years since the Endeavour returned, some such project had been much discussed by members of the Banks circle, finding one ardent advocate in Solander (until his untimely death in 1782) and another in Ellis who published a pamphlet on the subject. Banks himself laboured tirelessly to put the scheme into effect. The American war brought his efforts to a temporary halt, but with the coming of peace he renewed his solicitations until the plan won acceptance among ministers of the government and high-placed officials. At first one of the Botany Bay transports was to be used for carrying the plants. This proposal was abandoned, however, and the Bethia, renamed the Bounty, was specially fitted out for the purpose under Banks’s directions. He also recommended the appointment as commander of Lieutenant William Bligh who was well qualified for the post not only by his experience as master of the Resolution but by recent service in the West Indies. To undertake the delicate task of selecting and caring for the cargo went David Nelson, Banks’s collector on Cook’s last voyage, with an assistant. The expedition left England late in December 1787 and, after a trying passage by way of the Cape and Van Diemen’s Land, reached Matavai Bay on 26 October 1788.16

The Tahitians were delighted at the arrival of another ship so soon after the Lady Penrhyn of whose visit they hastened to supply a few particulars in answer to Bligh’s questions. Its captain was a man called Tonah, it had stayed a month, it had been gone four months or, as some held, only three. They in turn asked after Cook, Banks, Solander, and various members of the last British expedition. Despite Sever’s precautions in his dealings with Odiddy, someone on the ship had evidently told them of Captain Cook’s death. But they knew nothing of the circumstances, and these Bligh forbade his men to disclose. Three more fatalities the islanders announced quite positively: the ‘famous Old Admiral Towah so often spoke of by Captn. Cook’ was dead, and so were both Omai and the older New Zealand boy. Following Bligh’s inquiries, he learned that his two shipboard companions had died not in war but of sickness — one from ‘Epay no Etua’, the other from ‘Epay no Tettee’, which he took to mean mortal diseases sent by two different gods. The younger boy’s fate was not mentioned.17

Otoo, who was staying at another part of the island, sent a gift of hogs and plantains on the 27th with a message to say he would be at Matavai Bay the next day. Pending his arrival Bligh entertained the monarch’s relations, called on old friends, and visited familiar places. He was received with touching courtesy wherever he went and, in contrast with Watts, found evidence that British efforts to civilize these people had not been wholly in vain. They now fashioned their implements on European models and were eager to acquire files, gimlets, combs, knives, and looking-glasses. The produce they supplied in return, he noted with satisfaction, included shaddocks, capsicums, and goats, but he could learn nothing definite about the cattle left behind in 1777. In one respect he saw a marked improvement. The only thing stolen during the first couple of days was a tin pot and when its loss was discovered, Otoo’s brother flew into a violent rage and insisted that all thieves should be tied up and flogged. After this incident Webber’s portrait of Cook was brought to the ship for repair. The painting had evidently suffered some mishap since the Lady Penrhyn’s visit, for Bligh observed that a little of the background was ‘eat off’ and the frame slightly damaged.18

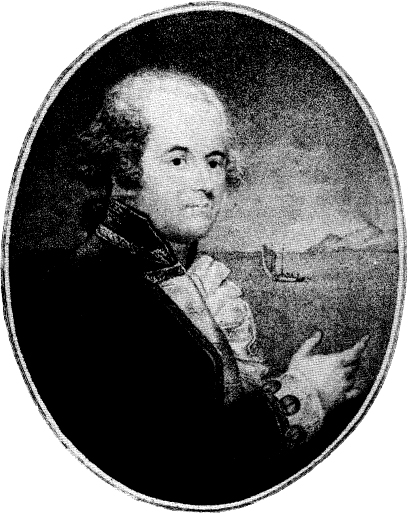

56 Captain William Bligh after J. Russal

Before beginning to gather breadfruit plants, Bligh thought it advisable to consult Otoo and the other chiefs, but early on the 28th he sent David Nelson ashore to spy out the land. About nine o’clock the same morning Fletcher Christian, the master’s mate and acting lieutenant, escorted Otoo to the ship with his wife Iddeah (Itia) and a train of their relatives and attendants. On both sides there was perfect amity from the outset. The Tahitian visitors brought cloth and produce, while Bligh more than repaid them with lavish gifts which included two red flamingo wings acquired at the Cape. During the ritual of welcome he learned that the high chief was no longer called Otoo. That name had passed to his eldest son, who live at Pare, and the father was known to his own people as Tinah (Taina). Otoo or Tinah (as he was henceforth indifferently termed) spoke without shame of his defeat by the invaders from Moorea, the loss of his precious livestock, and his flight to the mountains. He was ‘exceedingly frightned’ by two shots from the guns, fired at his own request, and ate ‘most voraciously’ throughout the visit which lasted until the late afternoon. In the evening Nelson returned to report that breadfruit seedlings grew abundantly in the neighbourhood and that two shaddocks he had planted in 1777 were now fine large trees covered with fruit.19

The bonds with Otoo-Tinah were strengthened when, on 1 November, Bligh paid a return visit to Pare. Here he realized the full consequences of Cook’s harsh policy in Moorea: there were no traces of the ‘palace’ or of the large chest fashioned by the Resolution’s carpenters; none of the substantial houses that once dotted the landscape; only two or three of the war canoes that formerly crowded the bay; and no signs of imported animals or poultry. Everything had been destroyed or carried off by the raiders who, Bligh was told, had joined forces with Towha to attack Otoo about five years after Cook’s departure. By that time the cows had eight calves, the ewes had ten young ones, and the birds, except only for the turkeys and peacocks, had multiplied many times over. Now not a single one was left. ‘Thus’, Bligh lamented, ‘all our fond hopes, that the trouble Captain Cook had taken to introduce so many valuable things among them, would by me have been found to be productive of every good, are entirely blasted.’ He regretted that they had not left everything at Huahine where, he learned from different people, great care was taken of Omai’s mare, though the stallion had died of natural causes. In spite of their misfortunes, Otoo and his family loaded their guest with gifts and entertained him at a heiva. He caught only a distant glimpse of the new ‘King’, a boy about six years old, who was carried on a man’s shoulders and lived in surroundings so beautiful and picturesque as to defy Bligh’s powers of description. He returned to Matavai in a mood recalling that of the bemused Bougainville. ‘These two places’, he exulted, ‘are certainly the Paradise of the World, and if happiness could result from situation and convenience, here it is to be found in the highest perfection.’20

He soon felt confident enough to explain his mission to the chiefs with whose approval the gathering and potting of breadfruit seedlings began early in November. Since the work was largely delegated to the capable Nelson and his assistant, Bligh himself was free to follow his own manifold interests. Deeply imbued as he was with the dead commander’s principles, his first concern was to continue Cook’s horticultural experiments and, if possible, repair the damage inflicted by the Moorean invaders. With help from the crew, he and Nelson had already laid out two gardens and sown them with Indian corn and vegetables. Now almonds were distributed with instructions on their cultivation, while fruit stones and rose seeds were planted in suitable places. The almonds formed part of a gift sent to Omai by the daughters of Mr. Brand, the commandant at the Cape, and Bligh thought he could not put them to better use. He had no animals to restock the island, but after infinite trouble he did succeed in bringing to Matavai two isolated remnants of Cook’s gift, a heifer and a bull, which quickly mated. On completing his arduous task, he expressed mingled feelings of loyalty and self-satisfaction:

Thus I have fixed in a fair way a Breed of Cattle in this Island, which after much trouble and care failed in the first instance and in all probability would never have taken place again, had it not been for this gracious Act of His Majesty our King to benefit his Subjects in the West Indies with the Breadfruit plant.

He was less fortunate with a sheep transported from Huahine by the chief Tareederia who told the sceptical Bligh there were ten more on the island. This one he identified as the English ewe left with Otoo in 1777, now reduced to mere skin and bone and afflicted with mange. Nevertheless, he bought the animal and in the hope of acquiring a ram offered a large reward if more sheep were retrieved. But before the poor creature could also be mated it was killed by a dog — or so the islanders reported. Bligh suspected they had made up the story for reasons of their own.21

These people, he had long since decided, thought lying a real accomplishment — their whimsical and fabulous accounts were ‘beyond every thing’. Yet this realization did not prevent him from recording fantastic travellers’ tales or doubtful and sometimes inconsistent versions of past events. Particularly baffling were the meagre and often vague statements about Omai and his young companions. On that subject the chief authority was Odiddy whom Bligh first mentioned on 4 November. Cook’s former protégé, now apparently reconciled to his lot, confirmed the earlier reports of Omai’s death and supplied a few more details: his house had been accidentally burnt down; his stallion was dead; his muskets were taken care of. Odiddy told Bligh that Tiarooa was also dead but Coaa, he asserted, was alive and very well. A week later Bligh heard from some unnamed informant that Omai had lived only thirty months after Cook left him at Huahine and Tiarooa not much longer. ‘Coah still remains there’, he wrote in his log, ‘and I have offered great rewards to any Cannoe that will go and fetch him, but as yet I have no hopes of seeing him.’ He added a comforting observation, evidently picked up from the same source: ‘Many enquiries were latterly made to Omai concerning England and it appears, poor fellow, that he impressed on their Minds not only our power and consequence, but our kindness and good will towards him.’ The next day Bligh was again cheered to learn — this time from Odiddy — that the vines and other plants left at Huahine continued to grow and bear fruit. Even more reassuring was the news that there were cattle on Moorea and that European plants still flourished at Vaitepiha Bay.22

If further reports were to be credited, Omai had long been outlived by the mortal enemy of his family and his people. On 13 November Bligh noted that Opoony, ‘the famous Old Cheif of Bolabola’, had died ‘30 Months since’. That day he made a determined effort to collect additional facts at a dinner attended, as usual, by members of the royal family and, on this occasion, by Odiddy. During the meal he steered the conversation to the subject of Omai, whereupon Odiddy spoke of the dead man’s martial exploits:

Soon after Captn. Cook left Huaheine there were some disputes between the people of that Island and those of Ulieta, in which also the Natives of Bola-bola or Bora-bora took a part. Omai now became of consequence from the possession of three or four Muskets and some Ammunition, & he was consulted on the occasion. Whatever were the motives, such was Omai’s opinion and Assurance of Success, that a War was determined on, and took place immediatly. Victory soon followed through the means of those few Arms and many of the Ulieta & Bora-bora men were killed. The Ammunition only lasted to end the contest, and they were in such want for flints that the Musquets were at last fired by a fire stick.23

Peace was again established, said Odiddy, ending his recital by repeating that both Omai and Tairooa had died natural deaths about thirty months after Cook’s departure. ‘I asked’, wrote Bligh, ‘if from this Victory Omai had gained any possessions or was of higher rank than we left him in.’ The first question was ignored, but to the second the guests answered without hesitation: no, he remained in the same rank as before, and that was only one above the lowest. At this point Bligh inquired about the different orders of Tahitian society. Instead of the commonly recognized three (arii, raatira, manahune), this royal and aristocratic assembly named six, ranging from King to Servants and including Lords, Barons, and Esquires. Omai was placed in the class of ‘Citizens’ — ‘Rateerah or Mana-hownee’ (which tended, if anything, to confirm his middling status).24

A fortnight later, with the arrival of Tareederia from the Society Islands, Bligh renewed his inquiries. This man had been the boy chief of Huahine at the time of Cook’s final visit and should have been well informed on Omai’s history. His reports, however, did not differ materially from earlier ones. Nor, apparently, was he able to clear up the mystery surrounding the young New Zealander, for Bligh complained: ‘… I cannot get any person to bring Coah (who is alive and Well) to me, or acquaint him that I am here.’ In the weeks and months that followed no more was said of the child (now, presumably, grown to manhood), while his master received only passing mention. On 8 December, when describing local manufactures, Bligh noted that since his previous visit there had been a vast improvement in the quality of cloth and mats. This he attributed to the attention which the Tahitian women had paid to the superior examples brought from the Friendly Islands by Cook and his men. Then, always ready to give credit where it was due, he added: ‘They have received a great deal of information from Omai. They give him a very good Character and say he knew and showed them a great many things.’ The banal tribute was Bligh’s last reference to Omai until he was preparing to leave the island towards the end of March.25

Bligh spent more than five months in Tahiti. None of his English predecessors had been there so long and no one, not Banks himself, had surpassed him in the range and persistence of his inquiries. While the collection of breadfruit plants went on, he examined local habits and customs, observing, listening, noting, but rarely condemning. He praised the undemanding hospitality of these unspoiled people, their friendliness to strangers, and their parental virtues, scarcely equalled, he thought, in the most civilized society. The phallic contortions of the arioi were certainly not to his taste; nor could he share Iddeah’s affection for her ‘Mahoo’ friend — boy in body, girl in manner — who, with others of the same kind, were ‘equally respected and esteemed.’ He inclined to the view that venereal diseases — or at least similar complaints — were endemic and not confined to the lower classes. The promiscuity of both sexes he regarded with an indulgent eye, and he even made light of petty thievery, more prevalent than he had first supposed. Where tolerance stopped short was in the treatment of his own countrymen. Early in the visit he introduced a practice, occasionally used by Cook, of penalizing not the native malefactor but the seaman through whose negligence the offence had been committed. These and similar measures understandably provoked the crew, and on 5 January three men made off with the ship’s cutter. Recaptured with the help of Odiddy, the deserters were put in irons and severely punished. Later that month, for striking a Tahitian he suspected of theft, another sailor was ordered two dozen lashes — a sentence Bligh reduced following the intercession of Otoo and Iddeah.26

This humane couple were Bligh’s constant companions. They paid frequent visits to the ship and late in November accompanied him to a great heiva where he shared the honours with Cook’s portrait which was displayed as a kind of sacred image. Three weeks later they showed ‘great attention and decency’ at the funeral of the ship’s surgeon who, having died from ‘drunkeness and indolence’ (Bligh’s harsh verdict), was buried ashore in a grave marked by a cairn of stones. The friendship grew even closer when on Christmas Day he moved the Bounty to the more sheltered harbour of Pare to escape seasonal gales. Henceforth he was in Otoo’s own district and entertained both the chief and his relatives almost daily. Through Odiddy, who served as his ‘spy on all their Actions’, he learned of intrigues in the royal family and of Iddeah’s open infidelities. Tolerant as always, he remarked on her good sense, her cleverness, and the vast sway she exerted over her husband. She displayed great interest in European arms, he noted, and always came aboard to fire the sentinel’s musket at sundown. Otoo, on the other hand, was ‘one of the most timrous men existing’, far surpassed in the martial arts by his youngest brother, renowned for having killed Maheine, the warrior chief of Moorea. Their mother, an aged lady of enormous corpulence, gave a long recital of the family’s misfortunes and pledged their eternal friendship. Among other visitors was one of the travellers to Lima and a venerable figure who claimed to be Tupia’s uncle. The patriarch still mourned the loss of his nephew and asked for the dead man’s hair to be sent back. When Otoo talked of going to England, Bligh remarked, he made the same plea on his own account should he, too, die while absent from his native island.27

Otoo did not embark on the Bounty, though both he and Iddeah with many others begged to be taken. As Bligh observed on 21 March, ‘… Omai has impressed on their minds so much in favor of England, that I could, if I had occasion for it, man the Ship with Otaheiteans, and even with Cheifs.’ One persistent volunteer was Odiddy, ‘a very worthy good Creature’, who was greatly attached to them, said Bligh, and anxious to accompany them, claiming it as his right ‘because he was at Sea with Captain Cook.’ Bligh fobbed off the suppliants with vague promises and excuses: before carrying them to his own country, he must get King George’s permission; Iddeah would die of seasickness; he would come back with a larger ship properly fitted out for their accommodation. To console them further, he distributed lavish gifts of shirts, hatchets, saws, files, knives, and, as a replacement for Cook’s stolen chest, he supplied Otoo with another, also large enough to serve as a bed. At the anxious chief’s request, for protection against predatory rivals, he gave Iddeah and Odiddy two muskets and two pistols with a thousand rounds of ammunition. He left the firearms with considerable hesitation and only, he said, because his friends, through their long-continued association with the British, had incurred the envy and hostility of their neighbours. Once the Bounty was gone, he was convinced they would again be attacked; and he regretted that owing to the demands of his present mission he had been unable to punish Otoo’s enemies for plundering him and taking his cattle. ‘If therefore’, he concluded, ‘these good and friendly people are to be destroyed from our intercourse with them, unless they have timely assistance, I think it is the business of any of his Majesty’s Ships that may come here to punish any such attempt.’28

In spite of some misgivings, Bligh could reflect that his visit had done something to advance Britain’s civilizing mission. Iron tools had now replaced the old implements of stone and bamboo, he recorded with satisfaction, while the islanders had become ‘immoderately fond’ of European apparel — their habit of wearing a single shoe or stocking rendered them ‘the most laughable Objects existing’. True, he must ruefully acknowledge, he had achieved little success with his gardens. The Indian corn had grown and ripened, but most of the vegetables had been destroyed by insect pests or trampled by marauding hogs. On the other hand, the two salvaged cattle promised to increase, and others, he was told, survived on Moorea. As for the official purpose of his voyage, it had succeeded beyond all expectations. When the Bounty left Pare on 4 April 1789, it was crammed to capacity with breadfruit seedlings. One of Bligh’s last acts was to inscribe the total — more than a thousand — on the back of Cook’s portrait and note other details of his stay. He restored the painting to his grief-stricken friends and sailed off. ‘That I might get a farther knowledge concerning Omai’, he explained, ‘I steered for Huaheine.’29

The Bounty reached the island shortly after noon on the 6th, but Bligh had no intention of landing at Fare and kept well outside the reef. ‘We could see every part of the Harbour very distinctly,’ he emphasized, ‘and my attention was drawn particularly to where Omais House stood, no part of which remained.’ The natives waited on shore for some time, expecting the ship to sail in. At last, about three o’clock, a small craft arrived, followed by a large double canoe with a crew of ten. Among them was a handsome young man who immediately greeted Bligh by name and proved to be one of the people the Resolution had brought to Huahine to live with Omai. This was a very fortunate circumstance, Bligh remarked, for the weather was squally and both he and his visitors were anxious to get away as soon as they could. For that reason, he added, the man’s account was very short but also very clear.30

What he related was indeed little enough, but he did settle the mystery of the younger New Zealander’s fate. Omai died thirty months after Cook’s departure, he told Bligh, and both Tiarooa and Coaa had died before their master, all three from natural causes. Of the animals only the mare still survived and nothing was said of the ten sheep reported by Tareederia. There lingered on, however, the memory of one small creature, now mentioned for the first time: ‘Omai had a Monkey with him which created great mirth among the Natives, they called it Oroo Tata or Hairy Man. This Animal he described as did the People of Otaheite, to have fallen from a Cocoa Nutt Tree and was killed.’ For the rest, the recital was one of almost unrelieved loss or neglect: Omai’s house had been torn to pieces and stolen; his firearms were at Raiatea; his plants had been destroyed except for a tree which the young man was unable to name. He went on to say that they often rode together, Omai in boots — a detail that Bligh seized on as encouraging proof that ‘he did not immediately after our leaving him, lay aside the Englishman.’ Omai’s influence was also evident in the tattooed horse and rider seen on the legs of several men and again in his companion’s urgent plea to be taken to England. Bligh declined the request, gave the young man a small present, and at six o’clock bore away from Huahine, making for the Friendly Islands. Three weeks later, on 28 April 1789, he was seized by mutineers, led by Fletcher Christian, and with eighteen others set adrift in the ship’s launch.31

THE UNCOMMUNICATIVE BLIGH apparently failed to pass on to his subordinates the details he had picked up concerning Omai. In his account of their five months at Tahiti, the boatswain’s mate, James Morrison, wrote of the crowd who first greeted them: ‘We also learnt by them that O’Mai was dead tho we could not learn by what means he died, but it was thought that he had been killd for the sake of his property’; ‘however’, he added, ‘we were better informd afterwards as shall be shown in its proper place.’ Again, in his reference to the call at Huahine on 6 April, he remarked: ‘At Noon we hove too of[f] Farree Harbour to enquire for Omai; but could get no other information but that he was dead some time.’ Morrison compiled his so-called journal while awaiting trial for his part in the mutiny and, since he denied all guilt, some bias in his own favour is only to be expected. Nevertheless, the journal (more accurately the narrative) was clearly based on diaries or notes and carries with it an air of authenticity. It remains, furthermore, the fullest record of the Bounty’s movements and the actions of its remaining men after Bligh’s involuntary departure. Morrison relates how, on taking charge, Christian ordered the breadfruit plants to be thrown overboard and, for reasons he did not yet disclose, set off for Tubuai in the Austral Group, sighted by Cook during the third voyage. On 28 May they reached the hitherto untouched island where events took a familiar course. The inhabitants tried to drive off the newcomers with clubs and spears, blew conch shells in defiance or used their women as decoys, and finally on the 30th launched a concerted attack which the Europeans repelled with their muskets and four-pounders. In spite of this hostile reception, Christian thought the place would make a suitable refuge for the twenty-five men left on the ship but first decided to visit Tahiti to take on supplies and recruit companions who might solace them in their exile.32

They again reached Matavai Bay on 6 June, to the surprise of their old friends who were told that after leaving the island in April Mr. Bligh had met Captain Cook and joined the commander’s ship with the breadfruit plants and some of his men. He himself had come back, Christian explained, to get animals for a settlement King George was forming in New Holland. The Tahitians appeared to accept the threadbare story of Cook’s continued existence and while Christian remained aboard, plying the chiefs with wine and arrack, agents went ashore to exchange ironware for livestock and provisions. The results exceeded all expectations. In ten days they acquired more than four hundred hogs and fifty goats with fowls, dogs, cats, and, most precious of prizes, the bull and cow Bligh had succeeded in bringing together with so much difficulty. The natives set little store on the two animals, Morrison remarked, and sold them for a few red feathers. Having loaded the Bounty, Christian and his men set out for Tubuai. They carried some volunteers and when they were at sea stowaways appeared on deck. Among them was Odiddy who had seized this opportunity of ending his long thraldom to Otoo. Christian told the migrants, numbering twenty-eight in all, that they would never see Tahiti again; but neither then nor later, Morrison observed, did they show the least sign of regret. On the voyage back the weather was stormy, resulting in the loss of some livestock. One casualty was the bull which died as the result of repeated falls and was heaved overboard.33

Like islanders elsewhere in the Pacific, the people of Tubuai had learned the harsh lesson of British power. When the Bounty returned on 23 June, there was no sign of hostility and, to improve matters, the Tahitians made friends with the local inhabitants and, picking up a knowledge of their tongue, were soon able to act as interpreters. Under these favourable auspices Christian had no hesitation in landing the animals, some of which were transferred to small islands in the lagoon, while the cow and about two hundred hogs were put ashore and ‘Sufferd to take their Chance’. Having disciplined two rebellious members of his crew, he sought a piece of land for the settlement he was planning. By playing off one group of natives against another (for this small island had its factions and its rival chiefs), he obtained a site where he intended building an elaborate stockade to be known as Fort George. On 18 July operations began with the turning of a turf, the hoisting of a union jack, and the drinking of a special allowance of grog. For the next month work went steadily forward.34

While Christian and his men toiled at Fort George, the latest visitors to Tahiti were picking up vague reports of their movements. On 12 August 1789 the brig Mercury, commanded by John Henry Cox, anchored in Matavai Bay. In explaining their presence in these remote waters, the historian of the voyage, Lieutenant George Mortimer of the Marines, was somewhat evasive. Though not wholly acquainted with Mr. Cox’s motives, he remarked, he understood that gentleman was ‘under an urgent necessity to go to China’ and chose to sail rather in his own vessel than in an Indiaman, ‘especially as he had a great desire to visit the Islands in the South Seas’. In fact the Mercury, also known as Gustaf III and employed by the King of Sweden in his war with Russia, was on its way to attack the enemy’s trading posts in the North Pacific. These mercenaries had no patience with the natives who crowded the ship on its arrival and no success in satisfying their curiosity about one renowned islander of whom they had probably read in accounts of Cook’s third expedition. ‘Our first enquiries’, wrote Mortimer, ‘were directed after Omai, the man whom Captain Cook brought to England, and who returned with him in his last voyage; but, notwithstanding we used our utmost diligence to gain any information concerning him, we could learn little else than he died a natural death, some time since, at the Island of Ulietea, his native place.’35

On landing, they found unmistakable signs of their predecessors — details of the Bounty’s visit on the back of Cook’s portrait brought to them by a local chief, the dead surgeon’s grave, and an English pointer which singled them out, showing its joy ‘by every action the poor animal was capable of’. As they walked on, they noticed vegetables ‘choaked up with weeds, and totally neglected by the natives, who set no kind of value upon them.’ There were no signs of Cook’s livestock, but on a later excursion Mortimer heard that some of the cattle were on the island of Moorea. One afternoon he saw a strange-looking club in the hands of a man who told him it had been brought from a place called Tootate by Titreano, Mr. Bligh’s chief officer. His informant went on to say that Titreano returned in the Bounty about two months after she first sailed, leaving Mr. Bligh behind at Tootate. Others confirmed the story and added that Titreano had left again only fifteen days before the Mercury’s arrival, carrying away several Tahitian families. At the time Mortimer had no idea who Titreano was or where Tootate could be; but ‘the principal part of this strange relation’, he later decided, ‘was true’.36

Iddeah soon paid her respects to Mr. Cox but Otoo, ‘the present king’, did not appear until the 16th, after which he was a constant visitor to the Mercury, often spending the night on board. He excelled his subjects not only in size, Mortimer noted, but also in appetite, for he ate enormously and quaffed wine very freely in honour of King George, a custom he had acquired on the Bounty. Like Bligh before him, the lieutenant compared the monarch most unfavourably with his consort, ‘a clever sensible woman’ and an excellent shot, as she proved by firing at a distant buoy which she hit at the first attempt. Other members of the royal family were frequent callers — Otoo’s equally bibulous brothers and their mother, one of the largest women Mortimer had ever seen but ‘a good motherly sort’ and ‘of a lively chearful disposition’. Otoo, who was undertaking a tour of the island, could not wait to farewell his guests when they finally sailed and, to their relief, left on the 23rd, entrusting them with a message to King George. His fellow monarch was asked to send a large ship that would remain at Matavai Bay and bring plenty of guns. He had already taken his presents away in a chest made for the purpose and this time carried off a living trophy. He was a sailor named Brown who a week before had ‘in a terrible manner’ slashed a crony with a razor and been put in irons. The man now told Cox he wanted to stay on the island and, as Otoo promised to care for him, the captain gladly let him go. When Brown left, he showed not the least sign of regret, nor did he take leave of a single person. The next day he wrote to say he was well treated, adding a request for a bible and tools to build a boat. Cox supplied the articles together with a letter of advice on Brown’s future conduct towards his protectors.37

Late in August, while the crew busied themselves getting the ship ready for sea, the officers crossed over to Moorea to see Captain Cook’s cattle (or their descendants). The Tahitians had warned them they would be killed, but they landed without opposition and while the excited islanders summoned their ‘king’, the visitors inspected a bull and two cows, all in good condition but very wild. The natives took little notice of the animals and set no value on them, Mortimer reported; indeed, he thought they must be an encumbrance rather than a benefit since there were no fences to keep them out of gardens and plantations. On his arrival, Maheine’s successor had little to say and seemed to be ‘of a timid disposition’. His wife, however, was an ‘agreeable, insinuating woman’ — so agreeable that she made her person available that night, as did another royal lady, claiming to have been the ‘Tayo’ of Sir Joseph Banks (presumably twenty years earlier when he came to observe the transit of Venus). Before they returned to Tahiti the sightseers rowed to Cook’s anchorage, ‘a most beautiful spot’, and by the 29th were back in Matavai Bay making final preparations for the coming voyage. On 2 September 1789 the ship set out on the next stage of its sinister mission, leaving behind Tahiti’s first British settler. As Mortimer reported in his introduction, he returned to England in time to tell Captain Edwards of the Pandora what he knew of the mutineers. His hope was that ‘these daring offenders’ would suffer ‘that condign punishment’ they so justly merited.38

At about this time the daring offenders and their companions were in some disarray on their island refuge. The people of Tubuai had shown themselves less docile than the Tahitians, and their women were far less accessible. So it was decided to abandon Fort George and split into two groups: one would return to Tahiti while the other, led by Fletcher Christian, would seek some even more remote hiding-place elsewhere in the Pacific. Before they could put the plan into effect, however, they ran into serious trouble. While rounding up their livestock they clashed with the islanders who were finally worsted after losing at least sixty of their men in battle. Morrison paid a tribute to the martial prowess of their Tahitian followers, especially Odiddy, ‘an excellent Shot’; and he recorded a farewell feast provided by Bligh’s treasured cow which, he laconically observed, ‘proved excellent meat’. On 22 September, three weeks after the Mercury’s departure, they were again anchored in Matavai Bay. Christian waited only long enough to land the dissident party with their possessions before taking on board a further complement of Tahitians and sailing off to his unknown destination.39

The men who had elected to stay behind, sixteen in all, first visited Pare to offer ‘the Young King’ gifts of red feathers and curiosities brought from Tubuai and the Friendly Islands. Odiddy had also left the Bounty and acted as their spokesman both at this and later functions when they were feasted and given a piece of land for their use. Otoo, or Matte (Mate) as Morrison called him, was absent in the southern part of the island, occupied with some mysterious business of his own, but sent each man a hog and a piece of cloth. They in turn dispatched their own presents by a delegation which returned with Brown, the razor-slashing sailor from the Mercury. He spoke openly of this and similar exploits, going on to complain that, while Captain Cox had given Otoo a musket and pistols, he had been left with neither arms nor tools. He ‘appeard to be a dangerous kind of a Man’, Morrison decided, and was relieved when he again left to rejoin Otoo. After a month or so the members of the ill-assorted group gradually went their separate ways. Some established themselves at Pare with their old sweethearts; several followed Brown to the south where they became involved in the intrigues of Otoo and other chiefs; the remainder stayed on at Matavai, living either independently or with their Tahitian friends. Once they had settled down, Morrison and his companions, none of them active conspirators in the mutiny, agreed to build a small schooner. They announced that it was intended for cruising among the islands; in reality, they hoped it would take them to Batavia and thence home to England.40

The work began early in November and went steadily on throughout the ensuing months. On Sundays and sacred holidays the men hoisted the ensign and held a service, often attended by the local people who behaved ‘with much decency’ and inquired into the mysteries of the Christian religion. The Europeans in their turn took part in Tahitian festivities, watching with interest when at a great heiva early in February the celebrants paid homage to Captain Cook’s portrait by stripping to the waist before the precious relic. As reports of dissension reached them from every quarter, it became evident that affairs on the island were in a dangerously unsettled state. On 9 March the young king, fearing an attack from hostile neighbours, summoned them to Pare to help him. This proved a false alarm, but some weeks later Otoo sent a messenger to ask their advice about settling scores with a recalcitrant chief on Moorea. Morrison and his party refused to be drawn into the quarrel, though they did clean and repair firearms for a punitive expedition sent over in charge of Odiddy. That redoubtable fighter carried out his mission with complete success, killing one leader and forcing the rebel chief to seek refuge with his relatives at Papara. Scarcely had this incident ended when news reached Matavai that, following the death of the Vehiatua, two mutineers settled in the south had both been murdered, one by his companion, the other by a native in retaliation.41

The boat-builders, in contrast, remained on good terms with their neighbours and resolutely persisted with their laborious enterprise. Early in July they finished the hull which was launched with the help of their Tahitian hosts and given the historic name Resolution. For the next few weeks they occupied themselves in completing the schooner and salting pork for the voyage to Batavia until they, too, were drawn into the factional struggle. As Bligh had predicted, the enemies of Otoo’s family combined to crush their rivals and, just as he had hoped, British mariners rallied to support his friends. On 12 September Morrison and his men again received a plea from the young king for help to repel invading warriors. This they succeeded in doing without much trouble, but later in the month a full-scale war broke out in which the contingent from Matavai joined other members of the Bounty crew together with Brown and Odiddy to crush the opposing forces. By the end of the month European tactics combined with European firearms had prevailed and at a gathering to ratify peace all the chiefs of Tahiti Nui promised ‘they would always honor the Young King as their Sovereign’. Proceedings were accompanied by volleys from the victorious muskets and ended with a great feast where conquerors and conquered mingled in seeming amity.42

Following this martial interlude, Morrison and his party returned to Matavai to put the finishing touches to the Resolution. By the beginning of November, just a year after they had begun work, the schooner was fitted out with masts, rigging, and temporary sails made of local cloth. They now felt they could venture from the bay to other harbours in Tahiti or to nearby islands. During a visit to Moorea they sought out the cattle, increased to seven since Mortimer’s census and, as Morrison remarked, ‘quite wild, being only kept as curiositys’. The chief purpose of the excursion was to procure woven matting for sails, but neither here nor in Tahiti could they find anything strong enough to withstand the stress of a long voyage as far as Batavia or even beyond. Some of the men, moreover, had grown lukewarm about that perilous venture. So, on their return to the bay early in December, they abandoned the idea of leaving their agreeable asylum. Since they expected the rainy season to set in shortly, they hauled the schooner ashore and built a shelter to protect her from the weather.43

IV Head of Omai (detail) by Sir Joshua Reynolds, c. 1775

Storms and squalls failed to deter the Society Islanders from traversing the miles of open ocean that separated them from Tahiti. There were many visitors ‘from different parts’, Morrison reported early in January 1791, noting in particular ‘the Ryeatea people, who made much inquirey about Captain Cook, Sir Joseph Banks &c. &c.’ Then came the long-promised revelations concerning Omai:

— and as we were also Visited by several people of note from Hooa-heine, the Island where Captain Cook had left Omai, we learnt of them that he died (of the Hotatte, a disorder not much different from the Fever & Ague) about four years after he had landed, and the New Zealand boys both died soon after, they greived much for Poenammoo their Native Country, and after OMai died, they gave over all hopes & having now lost their chief friend, they pined themselves to Death.44

In addition, the visitors supplied details (some of them clearly inaccurate) of Omai’s travels and his treatment by the islanders after Cook left Huahine:

— They also inform’d us that Omai was one of the Lowest Class (Calld Mannahownee) and had been condem’d to be sacraficed for Blasphemy against one of the Chiefs, but his Brother getting wind of it sent him out of the way, and the Adventure arriving at Taheite at the Time, he got on board her and came to England, and his Friendship with Captain Cook afterwards, made him more respected then his riches, and the meaness of his birth made him gain very little credit with his countrymen tho he kept them in awe by his arms.

Both the persons of note from Huahine and ‘a very intelligent man who lived with Omai some time as a servant’ spoke of the reputation he had achieved as a warrior:

… His Arms and the Manner in which he used them made him Great in War, as he bore down all before him, and all who had timely notice fled at his Approach and when accouterd with his Helmet & Breastplate, & Mounted on Horse back they thought it impossible to hurt him, and for that reason never attempted it, and Victory always attended him and his Party. Nor was he of less consequence at sea, for the enemy would never attempt to come near the Canoe which he was in.45

To questions about Omai’s property the islanders replied in contradictory terms. Some reported that he had been very careful of it during his lifetime, while others held that he scattered it widely. According to these informants, he had lost the stallion soon after landing in rather bizarre circumstances: the animal had been gored in the belly by a goat and, as he knew no remedy, Omai could do nothing but take revenge by killing the goat. The mare survived on the island and part of the house built by Captain Cook still remained. After Omai’s death, they said, his goods were distributed among his friends; one of them (Tareederia’s brother) had inherited the muskets, but they were of no use, ‘being both disabled’. For the rest, Morrison heard the familiar story of loss and neglect: Omai’s garden, ‘having no body to look after it’, had been destroyed by hogs and goats; except for one goose, his poultry were dead, ‘being devided and kept in different parts of the Island as Curiositys after His Death’ or taken elsewhere in the group.46

Morrison wrote nothing more about Omai and his possessions. On 10 January he reported the arrival of Iddeah, full of gratitude for the Englishmen’s services in the recent war. She had come, it soon appeared, to prepare for her son’s investiture with ‘the Royal Marro’, a momentous event which had no doubt also brought the visitors from the Society Islands. A month later, with elaborate ritual accompanied by thirty human sacrifices, the assembled chiefs acknowledged the young Otoo’s authority. At the ceremony the British nation, through whose influence a comparatively obscure family had risen to supreme power, was not unworthily represented by James Morrison. Late in March he was at Papara consorting with Oamo (‘the same mentioned by Captain Cook’) and his son when a messenger came from Odiddy to say that a ship had reached Matavai Bay. It was the Pandora, sent out to capture the Bounty’s crew and bring them to trial. Aided by Brown, the new arrivals rounded up the Tahitian contingent and on 19 May set forth again in search of Christian and his followers. They carried away both Brown and Odiddy who was left at the Society Islands, so passing out of recorded history nearly two decades after he first joined the Resolution.47

VETERANS OF COOK’S VOYAGES were serving at this period not only in the tropical Pacific but also in the ocean’s northern reaches where, with the coming of peace, they had found an occupation in the profitable fur trade between China and the north-west coast of America. While Bligh was engaged in his charitable mission, James Colnett, once a midshipman on the Resolution, had been employed to set up a trading post at Nootka Sound in what is now British Columbia. Arriving there in the Argonaut at the end of June 1789, he was confronted by a party of Spaniards sent to assert His Catholic Majesty’s rights and establish a colony. In the dispute that followed, the Argonaut was seized and its commander taken to Mexico, a prisoner in his own ship. After ‘Twelve Months and four days’ Cruelty, Robbery, and Oppressive treatment’, as he expressed it, Colnett was freed, but early in April 1791 he again clashed with a Spanish officer, Manuel Quimper, off the island of Hawaii. When reporting the incident in his journal, he wrote:

Manuel Quimper was in the Ship that Visited Oteihitee, when so much pains were taken to depreciate the English nation, which is taken notice of in Captain Cook’s Voyages; and this Quimper has been there since. When I was in Mexico I was inform’d from good authority that the Spaniards kill’d Omia, Destroy’d his dwelling, stock, and every other present, made him by the English, that they could come at, in the following manner: While the Ship lay at Huhana, they frequently Visited Omia at his house, and constantly lavish of their own praises, and no ways sparing of their abuse of the English. Omia, warm with Gratitude for the many favours he had receiv’d, hastily took up a Fowling piece, and Shot the Officer which was the second Captain, and a Frenchman, thro’ the head for which they retaliated.

On being charged with complicity in the murder, Quimper dismissed the whole story, but his denial did nothing to satisfy Colnett. In the Englishman’s view a nation which had thought it no crime to slaughter tens of thousands during a recent insurrection in Peru would not have hesitated to kill one individual.48

Colnett occupies a small niche in Pacific history not merely as recorder — or perhaps author — of the most sensational and obviously least authentic legend of Omai’s death. As a result of his misadventures, the Admiralty sent out a further expedition comparable with its predecessors and led by another officer who had served under Cook. Though Colnett had no official status when the Argonaut was seized, the British Government took up his cause and by mobilizing the Fleet compelled the Spanish authorities to restore the confiscated property and, even more important, acknowledge for the first time Britain’s right to trade and explore in the Pacific. Following this forced concession, the Discovery and a smaller supply ship the Chatham were commissioned to reclaim the Nootka Sound station and chart the west coast of America to the north of existing Spanish settlements. The command was entrusted to George Vancouver who had sailed as a midshipman on Cook’s second and third voyages. He was an able navigator and a highly intelligent man but apparently shared his old commander’s prejudice against specialized supernumeraries. He took no official artist, dispensed at first with the services of an astronomer, and raised objections to the appointment of Banks’s nominee, Archibald Menzies, as naturalist. Sir Joseph ultimately had his way and also secured a passage home for one more Polynesian wanderer, a Hawaiian youth from the Sandwich Islands known as Towraro or Towereroo (perhaps Kaualelu in modern transcription). Brought to England by traders in July 1789, he had since lived in great obscurity, Vancouver explained, ‘and did not seem in the least to have benefited by his residence in this country.’ They left Falmouth at the beginning of April 1791 and, sailing by the Cape of Good Hope route, reached Matavai Bay at the close of December.49

On arriving in the Discovery, Vancouver was relieved to find the Chatham already at anchor. The two ships had lost touch in a storm off the New Zealand coast, but William Broughton, the lieutenant in command, had succeeded in bringing his vessel to the appointed rendezvous and was already aufait with affairs on the island. Otoo was living on Moorea, it seemed, and was now called ‘Pomurrey’ (Pomare) by his own people. Though he still retained authority as regent, he had handed over sovereign power together with his former name to his eldest son who had invited Mr. Broughton to meet him that day at Matavai. Assured by native advisers that his presence would be ‘esteemed a civility’, Vancouver accompanied his colleague ashore where they paid their respects to ‘his Otaheitean majesty’. The monarch, a boy of about nine or ten carried everywhere on a man’s shoulders, at first treated the visitors with extreme reserve but later shook them by the hand and urged that a boat should be sent for his father. Vancouver agreed to the request and, encouraged by the warm reception he received from lesser chiefs and the common people, decided to prolong his stay, originally intended as a brief call to replenish supplies. He chose the site for a shore station and on the back of Cook’s portrait which, he remarked, had ‘become the public register’ saw that the Pandora had quitted the island in May. Improving on the words of his revered commander, he wrote of New Year’s Day: ‘lest in the voluptuous gratifications of Otaheite, we might forget our friends in old England, all hands were served a double allowance of grog to drink the health of their sweethearts and friends at home.’50

The next day Otoo-Pomurrey reached the bay, remarking as he saluted Vancouver that his English friend had grown much since they parted and ‘looked very old’. He brought with him a chief called Mahow (Mahau), ‘the reigning prince’ of Moorea, who seemed in the final stages of a decline, and they were followed by Iddeah and a younger sister with other members of the royal family. The captain treated the whole party to dinner, noting with surprise that the women sat at table with the men, though he believed the practice was not general. Both sexes, he observed, were anxious to adopt European customs and sought spirituous liquors avidly. In the course of the meal Otoo drank a whole bottle of brandy and in consequence suffered such violent convulsions that four strong men were required to hold him down. He learned the lesson of moderation, however, and by the end of the week restricted himself to a few glasses of wine. More notabilities soon arrived to greet the visitors — a kinsman of Otoo who after Opoony’s death had assumed power in Raiatea and Tahaa; the high chief of Huahine, also related to Otoo; and the latter’s two sons, the young king and his brother, recently created Vehiatua. As Vancouver perceived, ‘all the sovereigns of this group of islands’, save only Opoony’s daughter, were assembled at Matavai. To honour the distinguished gathering, on Saturday the 7th he entertained them at dinner and later with martial exercises followed by a display of fireworks. Hitherto Otoo had given Vancouver only trifling presents, but he now brought a truly regal tribute which included three specimens of the mourning dress, most precious of all Tahitian mementoes. On the 9th he left for Moorea, promising to return before the ships finally sailed.51

Throughout the Moorean party’s visit Mahow had been a pathetic figure, eager to inspect all things English but too feeble to walk and carried everywhere on a litter. On the 14th Otoo sent a messenger to say that the chief had died and mourning ceremonies would begin at Pare on the 17th. To ensure the Englishmen’s presence, early on the appointed day an escort reached the ships, but before he set out Vancouver saw fit to dispense justice to two natives. They had been caught stealing a hat from the Discovery and, in the hope that this might cure an epidemic of petty theft, he ordered their heads to be shaved and ‘slight manual correction’ administered. With that duty performed, he left to attend Mahow’s affecting and malodorous obsequies. The mourners soon recovered, for they arrived the next morning ‘in high spirits’ and were overjoyed when he promised them a second fireworks display to be held later in the week on the eve of his departure. All was amity for some days until thieves, undeterred by the captain’s harsh measures, stole a bag of linen; as a further complication, Towereroo, who had succumbed to the charms of a Tahitian girl, deserted and took to the hills. The Hawaiian youth was recaptured but all efforts to recover the linen failed and, to show his displeasure, Vancouver cancelled a heiva arranged in his honour together with the promised exhibition of fireworks. By the time he finally got away on the 24th, a reconciliation had been patched up and Otoo received the customary salute from the Discovery’s guns as the ships sailed on to the north.52

With becoming diffidence Vancouver apologized for shortcomings in his remarks on ‘a people whose situation and condition have been long the subject of curious investigation’. His stay on the island was short, he explained, his knowledge of the language limited, and his problems increased by ‘the difficulty of obtaining the truth from a race who have a constant desire to avoid, in the slightest degree, giving offence’. Certainly what he learned of Omai from Matuarro (Matuaro), the visiting chief of Huahine (doubtless Tareederia under a new name) added little to existing knowledge; and what he did record smacked somewhat of the official obituary:

Omai having died without children, the house which Captain Cook had built for him, the lands that were purchased, and the horse which was still alive; together with such European commodities as remained at his death, all descended to Matuarro, as king of the island; and when his majesty is at home, Omai’s house is his constant residence. From Matuarro we learned, that Omai was much respected, and that he frequently afforded great entertainment to him, and the other chiefs, with the accounts of his travels, and in describing the various countries, objects, &c. that had fallen under his observation; and that he died universally regretted and lamented.

Both he and the New Zealand boys had died of ‘a disorder … attended by a large swelling in the throat’. Most of its victims suffered a slow lingering death, they were told, and the fatal malady had been brought by a Spanish vessel which had anchored near the southern part of Tahiti.53

Omai and his retainers were gradually fading into the legendary past. Vancouver was more informative when he wrote of recent events in Tahitian history since he could still meet and question the chief actors. From Otoo and his brothers he heard of their defeat at the hands of Maheine and Towha, their temporary eclipse, and their gradual return to power. The ultimate victory he attributed to a number of causes — the help they received from the Bounty’s people, their possession of arms procured from visiting ships, and the combined and also complementary qualities of Otoo and Iddeah. Once peace was made, their elder son was firmly established at Pare, while his brother had lately been created Vehiatua. Through the authority vested in these children the family had gained control of all Tahiti and on the grounds of conquest or kinship claimed to be overlords of Moorea, Huahine, and Raiatea. Now they planned an attack on the territory which Opoony’s daughter had inherited from her father, insisting ‘it was highly essential to the comfort and happiness of the people at large, that over the whole group of these islands there should be only one sovereign.’ To achieve this end they asked Vancouver to supply them with more firearms and, when he was unwilling to comply, suggested he should conquer the islands on their behalf. He again refused, whereupon Otoo urged that on his return to England he should solicit King George to send out another ship for that purpose. He frequently made the plea, Vancouver related, and did not fail to repeat it in the most pressing manner as they finally parted.54