WHILE THE MEMORY OF OMAI GREW DIMMER IN THE TRADITIONS OF HIS OWN scriptless islands, his name lived on in European literature. Not only did he become the ‘gentle savage’ of William Cowper but also the central figure of an elaborate stage spectacle and the hero of a prose work epic in its scope and proportions. Duly described and labelled, he made his début as a natural history specimen, the representative of a new race. He continued to supply satirists with a pretext for their attacks on a decadent social order and remained the subject of debate between high-minded moralists and their more worldly opponents. Indeed, he was still sailing in mid-Pacific when he sparked off a controversy involving veterans of the second expedition and his former patrons. In March 1777 George Forster issued the two volumes of his Voyage round the World, a narrative of his experiences on the Resolution. In origin the work was partly at least a means of evading the Admiralty’s restraints on the elder Forster after the collapse of the scheme for joint authorship with Cook. Since John Reinhold was forbidden to publish until after the appearance of the official account, George took the enterprise in hand and, using his father’s material as well as his own, succeeded in anticipating by six weeks Cook’s Voyage towards the South Pole.1

As already related, Forster had been prejudiced against Omai from the outset, stigmatizing him as ill-favoured and dark-complexioned; furthermore, he alleged, the man’s low birth was clearly evident from the fact that on the Adventure he associated not with the captain but with the armourer and the common sailors. Yet, Forster conceded, Omai possessed some of the better qualities of his countrymen: ‘he was not an extraordinary genius like Tupaia, but he was warm in his affections, grateful, and humane; he was polite, intelligent, lively, and volatile.’ The last impressions were probably formed in England, for occasional references in Forster’s volumes make it clear that after his own return he had sought out Omai and consulted him on a variety of topics. According to his testimony, the Tahitians used no fewer than fourteen different plants for making perfumes, ‘which shews how remarkably fond these people are of fine smells.’ He again asserted ‘in the strongest terms’ that a race of cannibals, now extinct, had once lived in Tahiti and assured Forster that among the arioi it was the fathers, not the mothers, who were guilty of infanticide. From their conversation there also emerged a hitherto unrecorded (and perhaps apocryphal) incident in Omai’s history — that he had been among the attendants of Oberea and her husband when they were forced to flee to the mountains from their enemies.2

Forster was chiefly concerned, however, with Omai’s sojourn abroad, on which subject his comments were again scattered and his views often implied rather than stated. Both Omai and Tupia, he asserted, had left their homes in order to acquire firearms and so rescue their native island from its servitude to Borabora. Tupia, in Forster’s view, might have succeeded had he lived, ‘but O-Mai’s understanding was not sufficiently penetrative, to acquire a competent idea of our wars, or to adapt it afterwards to the situation of his countrymen.’ Nevertheless, he was obsessed with the idea of freeing Raiatea, his detractor continued, and before he returned often said that if Cook did not assist with his plan he would take care the captain received no supplies from his fellow-islanders. As for his stay in Britain, Forster hinted, it had been spent in frivolous pursuits or worse. When criticizing Cook’s refusal to allow the elder Forster to bring home a youth called Noona, the loyal son explained:

As it was intended to teach him the rudiments of the arts of the carpenter and smith, he would have returned to his country at least as valuable a member of society as O-Mai, who, after a stay of two years in England, will be able to amuse his countrymen with the music of a hand-organ, and with the exhibition of a puppet-show.

In a similar context Forster reflected that in view of Omai’s fate it was perhaps fortunate that Odiddy chose to remain in the South Seas: ‘The splendour of England remains unknown to him; but at the same time he has no idea of those enormities which disgrace the opulent capitals of the world.’ Here he failed to specify the enormities but, after claiming that prostitution was not universal in Tahiti, he went on: ‘It would be singularly absurd, if o-Maï were to report to his countrymen, that chastity is not known in England, because he did not find the ladies cruel in the Strand.’3

Having glanced obliquely at the subject in the course of the narrative, Forster returned to it in his preface. There he undertook to summarize the experiences in England of the native ‘vulgarly called Omiah’, though their substance would, he claimed, ‘furnish an entertaining volume.’ With a judicial air he began: ‘O-Maï has been considered either as remarkably stupid, or very intelligent, according to the different allowances which were made by those who judged of his abilities.’ His difficulties with the new language, for instance, had too often been misconstrued and were due to the fact that his native tongue with its profusion of vowels ‘had so little exercised his organs of speech, that they were wholly unfit to pronounce the more complicated English sounds’. In Forster’s opinion Omai was deficient not so much in intellect as in judgement. Introduced into genteel company on his arrival, led to the most splendid entertainments, and presented at Court, he adopted the manners and occupations of his companions, giving many proofs of a quick perception: ‘Among the instances of his intelligence, I need only mention his knowledge of the game of chess, in which he had made an amazing proficiency.’ On the debit side, the multiplicity of objects crowding upon him prevented his paying due attention to what would have been beneficial to himself and his countrymen on his return. Moreover, the continued round of enjoyments left him no time to think of his future; ‘and being destitute of the genius of Tupaï’a, whose superior abilities would have enabled him to form a plan for his own conduct, his understanding remained unimproved.’4

For that failure Forster, like earlier critics, blamed not Omai but his patrons. It could hardly be supposed, he asserted, that the visitor never expressed a wish to obtain some knowledge of English agriculture, arts, and manufactures; ‘but no friendly Mentor ever attempted to cherish and to gratify this wish, much less to improve his moral character, to teach him our exalted ideas of virtue, and the sublime principles of revealed religion.’ Yet the scenes of debauchery almost unavoidable in the civilized world had not corrupted the ‘natural good qualities’ of Omai’s heart. At parting from his friends his tears flowed plentifully and his behaviour proved him deeply affected. On the other hand, he was not entirely uncorrupted since he carried with him ‘an infinite variety of dresses, ornaments, and other trifles, which are daily invented in order to supply our artificial wants.’ For, as Forster went on to explain,

His judgment was in its infant state, and therefore, like a child, he coveted almost every thing he saw, and particularly that which had amused him by some unexpected effect. To gratify his childish inclinations, as it should seem, rather than from any other motive, he was indulged with a portable organ, an electrical machine, a coat of mail, and a suit of armour. Perhaps my readers expect to be told of his taking on board some articles of real use to his country; I expected it likewise, but was disappointed. However, though his country will not receive a citizen from us much improved, or fraught with valuable acquisitions, which might have made him the benefactor, and perhaps the lawgiver of his people, still I am happy to reflect, that the ships which are once more sent out upon discovery, are destined to carry the harmless natives of Taheitee a present of new domestic animals.

Unconsciously supporting Cook and extending optimism even farther, Forster thought the introduction of cattle and sheep to that island would increase the happiness of its people and, ‘by many intermediate causes’, improve their intellectual faculties.5

Though by no means novel, Forster’s views were expressed fully and with exceptional force and would be drawn on by a succession of writers, including the missionary Ellis. The immediate response was a pamphlet by the Resolution’s astronomer, William Wales, who, there is little doubt, had the support of Banks and Sandwich. Having quoted the contemptuous reference to Omai’s organ, electrical machine, and armour, he asked why Forster had not specified what articles would have been ‘of real use’ to the returning voyager. ‘Omai’, he continued, ‘carried out, or was furnished at the Cape of Good Hope, with horned cattle, sheep, geese, turkies, &c. and also with a horse and two mares, for whose reception, he gave up, with cheerfulness, his cabbin, and betook himself to the more inglorious accommodation of a common hammock.’ Since the last particulars could have come only from Cook’s private letters to the First Lord and Banks, it is fair to assume that Wales had consulted one or both of the two men. His remarks on Omai may thus be taken as in some measure a defence of their much criticized treatment of the visitor during the two years he spent under their protection.6

In this section of his pamphlet Wales attacked Forster for his suppression or distortion of facts as well as for the falsity and superficiality of his reasoning. Omai, he pointed out, had been given not only musical instruments and toys but animals, poultry, axes, saws, ironwork — indeed every article whatsoever that was valuable in the islands. What else, then, would Forster have put on board? True, he was not furnished with a profusion of things for which he had not the least inclination or which only ‘the merest speculative reasoner’ could suppose to be of use to his people. Similarly, it was thought unnecessary to ‘teaze’ him with a knowledge of English agriculture, arts, and manufactures. These were by no means so well adapted to his surroundings as his own pursuits and, furthermore, could not have been carried on unless ships were sent there every year with raw materials. Even then Forster’s proposals would have answered no other purpose than to gratify the curiosity of Europeans and demonstrate the clumsy manner in which natives imitated them. For (to continue the summary of Wales’s verbiage) it was the work of many years for a man to master but one single art or manufacture, assisted though he was by all the skill and experience of ages. In the case of poor Omai it would have been necessary for both him and his teachers to learn a new language, nay to create a new set of ideas. With a body never inured to labour, a mind little used to reason, he was in the compass of a year or two to acquire a knowledge of English arts and manufactures; afterwards he was to put them into practice under many disadvantages amongst a people who, because they could not possibly foresee their use, would deride rather than assist him. If Forster and others who had been pleased to express themselves very freely had but considered all this, urged Wales, they would surely have written with more diffidence and less asperity.7

Wales passed lightly over the charge that Omai’s patrons had failed in their duty by not introducing him to the beliefs and ethics of Christianity. ‘To as little purpose’, he asserted, ‘would it have been to teach him “our exalted ideas of virtue, and the sublime principles of revealed religion,” in order “to improve his moral character” ….’ Every reasonable man, he held, must foresee that once Omai had gone from amongst us he would never again think of such matters. Or, if he did, was it to be expected that they would have more influence on him than they did on some of ourselves? And Wales instanced those of his fellows who with moral principles continually in their mouths were at the same time endeavouring to hack to pieces the reputation of a neighbour or ‘trying, by every piece of artful chicanery, to undermine his property.’ With that innuendo, possibly directed at John Reinhold, he left the subject of Omai to criticize other views put forward by the unpopular pair.8

By no means quelled by the astronomer’s onslaught, Forster returned to the attack. If, he retorted, Mr. Wales failed to see that during his stay Omai could have more usefully employed his time than at Court or in the theatres, the Pantheon, the taverns, and other scenes of dissipation, then any attempt to enlighten his own intellect and mend his morals might prove unsuccessful. Mr. Wales, he exclaimed incredulously, thought that a man with a good heart — and Omai really possessed such — after being taught to form a rational idea of virtue, to comprehend the importance of religion, and to believe its divine origin, would forget these glorious truths and never think of them again after he departed! Would not every virtuous reader, the pious young naturalist inquired, think that this doctrine, which placed in a contemptuous light all that was sacred and respectable amongst men, most unerringly betrayed its secret author?9

After delivering this dark shaft (perhaps aimed at his father’s enemy, the adulterous Sandwich), Forster dwelt on more mundane matters. Mr. Wales, he went on, asserted that our arts and manufactures were not so well adapted to the climate of Tahiti as to our own. But did it follow that none of our arts deserved to be transplanted thither? And would there have been no benefit if the returning voyager could have taught his countrymen to perform in a day what now cost them weeks and months of tedious labour? More explicit than his predecessors, Forster supplied practical reasons for introducing European amenities to the islanders:

The more their labour is abridged, the more time remains for reflection, and for the improvement of social and moral felicity. O-Mai might have been taught to fabricate iron into tools, to make pots and other vessels of clay, to prepare from cotton, and from grass, more lasting garments than the bark of a tree, and to improve the knowledge of agriculture among his countrymen. A ship load of raw materials would not only have served him, but made happy many generations of Taheiteans, particularly if hints had been given him to search for some of these articles, such as iron, clay, and cotton in his own country. It is next to a certainty, that the chiefs of the country will strip him of all his riches, the moment after Captain Cook is sailed from thence; he then returns to his first insignificance; whereas, had he been taught a trade, his knowledge would always have been real riches to him, and paved his road to honour and opulence among his countrymen.

Before leaving the subject of Omai to take up different issues with his antagonist, Forster corrected one of that gentleman’s misconceptions: ‘Mr. Wales insists much on the utility of introducing cattle at Taheitee; and if he hath carefully examined my preface, he must have perceived, that I am far from censuring this step; but I cannot help smiling when he talks so pompously of “poor O-Mai’s” horses.’ The ‘real use’ of those animals on a small island could, he held, be only the gratification of the owner’s vanity. By displaying feats of horsemanship he would ‘become an object of wonder and amazement to the inhabitants, and give the poets of his country an opportunity to revive the fable of the Centaurs.’10

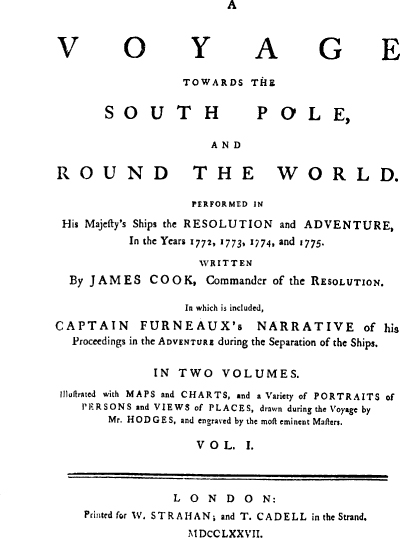

WHILE GEORGE FORSTER CARRIED ON HIS DEBATE WITH WALES, A Voyage towards the South Pole had made its triumphant appearance. Cook’s own narrative of perhaps the most romantic of his expeditions was immensely popular from the outset, soon ran into three editions, was quickly translated into other European languages, and won the captain novel acclaim as author with renewed praise for his feats as explorer. He had expressed himself ‘with a plain natural strength and clearness, and an unaffected modesty which schools cannot teach’ was the opinion of an unnamed writer in the Gentleman’s Magazine who claimed that in the role of navigator Cook undoubtedly ranked as ‘the first of this or any age or nation’. The reviewer touched on outstanding incidents in the voyage — the ‘transmutation’ of sea ice into fresh water, the assembling of the great fleet of war canoes at Tahiti, the supposed sale of children at Queen Charlotte Sound — but refrained from retelling the ‘horrid tale’ of the Adventure’s boat crew, an episode that confirmed beyond doubt the New Zealanders’ custom of eating human flesh. Much more pleasing, he said, were Cook’s remarks on Omai. These he quoted in full while expressing the hope that the islander was now ‘alive and merry among his countrymen’. He lavished praise on the admirable engravings after Mr. Hodges and ended with a brief reference to George Forster’s book: though undoubtedly of merit it was not only superseded by the present work but was ‘invidious and interested’.11

Of the highly miscellaneous offspring — or putative offspring — of Cook, Forster, and lesser accounts of the expedition, the earliest was a satire published anonymously but now ascribed to an Irish poet-dramatist, William Preston. Seventeen Hundred and Seventy-Seven, further diffuse addition to the Oberea cycle, is grandiosely entitled a ‘Picture of the Manners and Character of the Age’ and described as ‘An Epistle from a Lady of Quality, in England, to Omiah, at Otaheite’. The picture displayed is that of folly and corruption common to works of this kind, and neither correspondent nor recipient becomes more than a shadowy counter. With Banks and the other stock figure of Tahitian satire the returned voyager is invoked in the opening lines:

If yet thy land preserves Opano’s name,

And Oberea pines with am’rous flame;

If joys remember’d rapture can impart,

And London lives within Omiah’s heart;

Dear shall this greeting from thy Britain prove,

And dear these wishes of eternal love.

In a reference to Sandwich, lightly disguised as Rufo, Omiah is presented not as his lordship’s cherished protégé but in terms that would have won Forster’s approval, as the victim of that supposedly licentious nobleman:

For British navies own his forming hand,

And, lur’d by him — Omiah blest the land.

His gentle mind with polish’d arts he stor’d,

And stews, and palace, with his guest explor’d.

And say, Omiah! does thy heart complain

Of fates, which call’d thee to the British plain?12

In the face of this sinister precedent, the Lady of Quality makes no attempt to deter other southern visitors; quite the reverse in fact. In so far as her purpose may be discerned through her indiscriminate condemnation of French novels, Italian fashions, and English morals, it is to persuade Omiah’s compatriots to follow his example:

These faithful lines shall tell thy native train,

What honours court them to the British plain.

Oh, may the picture tempt the youths to rove,

And bring their pleasures, and their arts of love!

Let sooty throngs the cream-fac’d courtiers shame,

And southern lovers glad the curious dame ….

These virile immigrants will bring to ‘Britannia’s shore’ the arts and diversions of Tahiti, such as (in allusion to Banks and Oberea),

Luxurious feasts by blest Opano seen,

Instructive pageants of an am’rous queen.

They will establish the arioi society described by Hawkesworth and introduce the custom of infanticide, so that

Intruding babes shall bleed as soon as born,

And pleasure bloom divested of its thorn ….

The flow of migrants, however, need not be confined to Tahitian youth: in her final rousing address, while renewing her invitation to nature’s children, the Lady of Quality foresees a two-way traffic between north and south, with a visit to Oberea and her kingdom replacing the conventional tour of Europe:

Our silken youths for you shall cross the line,

To dress your females and your boards refine;

Each travell’d peer shall bless you in his tour

With arts of play, and secrets of amour.

. . . .

Then shall perfection crown each noble heart,

When southern passions mix with northern art;

Like oil and acid blent in social strife,

The poignant sauce to season modish life.13

But would northern visitors still find the tropical paradise uncovered by their predecessors more than a decade before? Another Irish writer, identified as the Revd. Gerald Fitzgerald, thought otherwise and presented his conclusions in The Injured Islanders; or, The Influence of Art upon the Happiness of Nature, published anonymously in 1779. Citing in his support a passage from George Forster, he asserted in a preface that, whatever the benefits to commerce and science, Pacific exploration had brought only suffering to ‘the innocent Natives’. The false value they placed on European trifles together with the ravages of ‘a particular Disorder’ had, he held, undermined their morals and destroyed their peace. Explicitly rejecting the satiric mode, he placed his versified sermon in the mouth of Oberea (or ‘OBRA’) who, in a further breach with tradition, addresses not Banks but Wallis. She recalls the happy state of her kingdom before his arrival,

When kindred Love connected ev’ry Shore,

When mutual Interest, spreading unconfin’d,

Parental Care and Filial Duty join’d ….

Now, since ‘Europe’s Crimes with Europe’s Commerce spread’, all is changed:

Discord and War in dread Confusion rise,

With Widow’s Wailings, and with Orphan’s Cries ….

Social life is poisoned at the source by the dread contagion introduced by some ‘vagrant’ of ‘ever-hateful Name’:

Thro’ ev’ry Nerve th’ infectious Terrors rove,

Sap the shrunk Frame, and taint each Source of Love ….

Oberea herself, ‘Remov’d from Power’ by her rivals, looks for salvation in the return of Wallis and, at the rumoured approach of a ship, hurries to the shore; but ‘In vain I haste, — no WALLIS meets me there ….’ In her extremity she dispatches a trusted envoy to summon the captain:

Hope flies to Thee; thy Guidance to implore

I send TUPIA to the British Shore —

Send, but in vain, alas, his hapless End!

Lost was my statesman, Counsellor, and Friend ….

Omai now makes his appearance in a novel guise, as Tupia’s successor and Oberea’s messenger to Wallis:

Lo! next OMIAH dares the task pursue

And bears this fond Commission to thy View,

Asks, and entreats in OBRAS injur’d Name,

Thy wish’d for Presence to restore her same….

This mission, she is convinced, will be successful. Wallis will revisit Tahiti and replace her on the throne:

Thy faithful OBRA, aided by thy Hand,

Again shall rise, the Empress of the Land,

. . . .

Her Wrongs redress, her Regal Rights restore;

Till, smiling Peace thro’ every Region seen,

She rules triumphant, and expires — a Queen.14

After attracting a succession of versifiers since the publication of Hawkesworth, the Oberea cycle was showing signs of exhaustion and soon came to an ignominious end. In the same year, 1779, appeared the anonymous Mimosa: or the Sensitive Plant, since traced to the pen of another witling, James Perry. Dedicated to Banks, addressed to ‘Kitt Frederick, Dutchess of Queensberry, elect’, the poem is supplied with the same mock-scholastic apparatus as most of its forerunners and abounds in references to obscure personages and forgotten scandals. In his dedication the writer pays a tribute to Banks ‘whose desire of acquiring knowledge has led him to climates, most happily adapted to the nourishment and the cultivation of that wonderful lusus naturae.’ The ‘plains of Otaheité, he continues, rear this plant to an amazing height, ‘and Queen Oberea, as well as her enamoured subjects, feel the most sensible delight in handling, exercising, and proving its virtues.’ Furthermore, ‘Your friend Omiah, hath confessed … that the true and native soil of England, is exquisitely prepared for the reception of the plant; will raise it to very vigorous extent; feed it with the most vegetative juices; and promote its articulations, with as much kindness and animating warmth, as the sultry soil of Otaheité’ Italicized innuendoes in profusion, both here and in the body of the work, make it clear that the sensitive plant was a hitherto uncelebrated part of the Polynesian anatomy, the penis.15

While poetasters of the Pacific pursued their titillating themes, prose writers followed a more sober course. In 1778 an anonymous and still unidentified author had opened up new imaginative territory with a work bearing an elaborate title-page that also summarized the contents: The Travels of Hildebrand Bowman, Esquire, Into Carnovirria, Taupiniera, Olfactaria, and Auditante, in New-Zealand; in the Island of Bonhommica, and in the powerful Kingdom of Luxo-volupto, on the Great Southern Continent. Written by Himself; Who went on shore in the Adventure’s large Cutter, at Queen Charlotte’s Sound New-Zealand, the fatal 17th of December 1773; and escaped being cut off, and devoured, with the rest of the Boat’s crew, by happening to be a-shooting in the woods; where he was afterwards unfortunately left behind by the Adventure. An epigraph ran:

An Ape, and Savage (cavil all you can),

Differ not more, than Man compared with Man.

In a facetious letter to Banks and Solander, the writer requested permission to dedicate the book to them: as his friend Omai was indebted to their protection which they gave in grateful remembrance of favours received in his native country, he flattered himself they would not refuse him their patronage merely because he was born in England. At one point in the narrative Bowman mentioned Omai’s arrival on the Adventure and claimed to have acquired from him ‘in a tolerable degree’ his own knowledge of the Tahitian language.16 But apart from such incidental references, Bowman’s celebrated friend had no part in the proto-novel. It was concerned in fact not with one islander but with a wide range of Pacific denizens in all their imagined diversity.

The sole survivor of the Adventure’s cutter tells how he made his way back to the ship’s anchorage, only to find it had sailed. Crossing Cook Strait to escape the Carnovirrians (as the inhabitants of Queen Charlotte Sound are termed), he enters the country of the Taupinierans, a people even more primitive than their cannibalistic neighbours. Pygmies in stature, they have porcine faces and are equipped with rudimentary tails. Their vision is mole-like so that they sleep in caves by day and emerge at night to fish in the sea and gather shellfish on the beaches. They communicate in grunts and possess no form of government nor any religion beyond ‘a kind of veneration for the moon’. Bowman next crosses the lofty range of mountains enclosing Taupiniera and reaches the land of Olfactaria inhabited by a race endowed with superhuman powers of scent, a gift they employ in continual hunting. They speak the Tahitian language, worship the sun and moon, and though experienced warriors are not cannibals. Indeed, their inveterate enemies are the Carnovirrians who attack them in force and are vanquished through the the hero’s skill in military tactics. So Hildebrand avenges his murdered companions, but his martial prowess provokes the jealousy of rivals and he moves on to Auditante. This fourth division of New Zealand is populated by tribes who wander about with their flocks and herds and their trains of slaves and wives. They are polygamous and idolators, use a form of script resembling Hebrew or Arabic, and are so idle that they make no attempt to manufacture wool or other products of their animals. Gifted with the most acute hearing, they spend their abundant leisure in listening to music or recitals of poetry and in al fresco feasting. The disapproving and somewhat dour Bowman (a Yorkshireman like Cook) finds such pleasures cloying and leaves the country with a party of visiting merchants for the island of Bonhommica. This proves to be the true earthly paradise, no licentious Cythera but a nation of modest, industrious citizens, ruled over by a benign monarch and united in the practice of their austere religion. Thence Hildebrand travels to one of the kingdoms of the Great Southern Continent, Luxo-volupto, where he finds a large population living in magnificent surroundings but given up to vice and self-indulgence. They have numerous priests and ostentatious temples, but these do nothing to curb the ‘universal profligacy’ that confronts the censorious but ruttish Bowman. The adventurer finally returns to Britain in March 1777, concluding that the manners of his countrymen resemble those of the Luxo-voluptans more closely than the sober ways of the Bonhommicans.17

Hildebrand Bowman seems to have been the work of a Grub Street journeyman, familiar with the gossip of learned London, who set out to exploit the speculative interests roused as well as appeased by Cook’s discoveries. The book is no Gulliver and no Rasselas, but it belongs to the same order of imaginary travels and embodies in a crude form current theories about human society and the South Seas. The Taupinierans, it has been convincingly shown, illustrate Lord Monboddo’s views that man in his primitive state retained many characteristics of the animal and led an isolated, brutish existence.18 To follow up this clue, the Carnovirrians may be seen to embody the second step in the evolutionary scale, while at the next level are the Olfactarians who, though retaining some savage characteristics, no longer devour their own kind. Then come the Auditantines, pastoral nomads living, as Hildebrand remarks, in a state resembling that of the biblical patriarchs. Bonhommica, to which he later transfers himself, marks the peak of human felicity — an eighteenth-century state shorn of its defects. Lastly there is Luxo-volupto which represents civilization in its decline and supplies the author with opportunities for scourging the vices of his age and his country. The physical peculiarities shown by certain of these people — the mole-like sight of the Taupinierans, the acute sense of smell displayed by the Olfactarians — may illustrate the idea of adaptation or, possibly, some notion of antipodean reversal, a variation on Othello’s ‘men whose heads do grow beneath their shoulders’. On the other hand, they may be nothing more than the pointless inventions of a hack who in this way supplemented the mildly salacious details he sprinkled throughout the text.

Bowman’s creator thought it necessary to touch on the religious condition of Pacific peoples, a subject to which a nameless satirist later applied his meagre talents. Some time in the early seventeen-eighties there appeared A Letter from Omai to the Right Honourable the Earl of ********, Late — — — Lord of the — — —. Translated from the Ulaietean Tongue. The crowded title-page claimed to expound ‘The Nature of Original Sin’ and to outline ‘A Proposal for Planting Christianity in the Islands of the Pacific Ocean.’ Addressed from Raiatea, where the author evidently supposed Omai to have settled, the letter is dated 2 October 1780; but the pamphlet itself must have been published after March 1782 when Sandwich, obviously referred to in the title, left office. Presented in tract form, the letter opened with disarming politeness: ‘My Dear Lord, I take this opportunity, the last perhaps I may ever have, of inquiring after your Lordship’s health; as also of thanking you again for the many favours I received at the hands of yourself, and your friends.’ The writer’s real intention becomes clear in the next sentence with its echoes of Forster and other critics of Omai’s patrons: ‘And after thanking you for the powder, shot, gun, crackers, sword, feathers, and watch, let me thank you also for my conversion to Christianity …’19

This sarcastic attack on the discredited Sandwich for his failure to concern himself with the voyager’s spiritual welfare leads to the promised examination of the doctrine of original sin. As a result of visiting Britain and hearing Christ’s message, Omai asserts, he has, according to Methodist beliefs, rescued himself from eternal damnation. But what, he inquires, is the situation of his unregenerate countrymen who have not enjoyed the same advantages? Here he considers the plight of his pagan cousin Twainoonoo:

… Twainoonoo is under the general condemnation of original sin. — I ask, may he not also be included in the general atonement made by the death of Christ? — A Methodist will say no, because Twainoonoo never having heard of Christ, and consequently not believing in him, cannot be benefited by his intercession. — But, God help him, what, in such a situation, is to condemn him? Original sin. That is original condemnation; or, in other words, Twainoonoo is damned to all eternity for being born.

The Established Church fares no better than Methodism at the hands of this sceptical convert who suggests that one ambitious ecclesiastic might become ‘archbishop of the Great Southern Ocean’ and recommends lesser clerics made redundant by the decline of faith in Britain to volunteer as missionaries. In passing he criticizes the conduct of the American war and aims his final shaft at one of the unlikeliest of targets: ‘I cannot conclude my letter, without saying how much real concern I feel for the unfortunate fate of poor Captain Cook, who was certainly very cruelly and inhumanly butchered, for nothing more than ordering his crew to fire on a banditti of naked savages, who seemed to look as if they had a right to the country in which he found them.’20

THE GRATUITOUS GIBE must have struck a uniquely discordant note at a time when adulation of the dead navigator was universal and the public clamoured for printing after printing of Anna Seward’s Elegy on Captain Cook with its invocation to Tahiti and the island’s notabilities:

Gay Eden of the south, thy tribute pay,

And raise, in pomp of woe, thy Cooks Morai!

Bid mild Omiah bring his choicest stores,

The juicy fruits, and the luxuriant flow’rs;

Come, Oberea, hapless fair-one! come,

With piercing shrieks bewail thy hero’s doom!21

Miss Seward’s banal tribute, first issued in 1780, was followed by works from members of the expedition who in defiance of Admiralty orders had retained their papers. Early on the market, in 1781, was the anonymous Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage, attributed to John Rickman, second lieutenant on the Discovery. With its melodramatic frontispiece depicting Cook’s death, the small octavo volume was calculated to appeal to readers eager for details of the hero’s end and met with instant success. Quickly running into a second edition, it was translated in France, pirated in Ireland, and plagiarized in America. The briefer account by Heinrich Zimmermann, able seaman on the Discovery, came out in the same year as Rickman’s. The author attached his name to the modest book but escaped any official consequences by writing in his native tongue and publishing in Germany. William Ellis, who had acted as surgeon’s mate on both ships and for his services won the dying gratitude of Captain Clerke, boldly acknowledged authorship of his two-volume Authentic Narrative which appeared early in 1782 and was reprinted the next year. Ellis, however, lived to regret his transgression. He earned the displeasure of Sir Joseph Banks and, as that gentleman informed him, by ‘so imprudent a business’, forfeited all hope of preferment with the Admiralty.22

As occasional consultant and minor collaborator, Banks of course had a proprietary interest in the official Voyage to the Pacific Ocean which after many delays at last made its appearance in June 1784. Rival publications proved to have whetted rather than appeased the popular appetite. Priced at four and a half guineas, the three volumes sold out in a few days, were immediately reprinted, and soon found translators in the major European countries. Of all the accounts of Cook’s travels this was perhaps the most widely read and acclaimed for reasons that are not far to seek. When editing the manuscript, Canon Douglas had ventured to assert that readers would be chiefly interested in the story of Omai; here he overlooked the one episode that loomed largest in contemporary eyes. The work, proclaimed a reviewer in the Gentleman’s Magazine, did honour to the English nation: to the King and his ministers who had planned the expedition; to the officers who undertook it; to the authors and illustrators; ‘but, above all, to the memory of that unparalleled navigator whose name it bears, a name semper honoratum, semper acerbum, and whom all succeeding ages will ever revere and lament.’ Since the magazine had already summarized the events of the voyage (in Rickman’s version), the writer merely added two lengthy extracts, the first being Captain King’s description of Cook’s death in Hawaii. Yet Douglas was not wholly wide of the mark, for in two further issues subscribers were entertained with a detailed narrative of Omai’s doings based on ‘all those passages which relate to the celebrated native’.23

Within a short time of publication Cook and King’s quarto volumes were to be found in genteel libraries, sometimes competing for attention with more sophisticated literature, as Fanny Burney testifies. Late in 1784 she was in the country, seeking solace among her new friends the Lockes for the rupture of her intimacy with the widowed Mrs. Thrale who, to the consternation of the Streatham circle, had recently married the Italian singer Gabriel Piozzi. Writing to her sister Susan, Fanny mentioned that on wet days she read extracts from ‘Cook’s last voyage’ while Mrs. Locke in her turn diverted the company with the Letters of Madame de Sévigné. They went on but slowly with Captain Cook, she wrote a week later, for ‘this syren’ de Sévigné had seduced them from other authors. The same year another rural household gathered for a similar purpose, but more seriously and single-mindedly, around the person of William Cowper. As the readings continued throughout the summer and autumn, the poet sometimes passed on his impressions to clerical acquaintances: the pleasure he derived from the descriptions of tropical scenes; his interest in the ‘exquisite’ dancing of the Friendly Islanders, unsurpassed, he thought, on the European stage; his sombre conviction that Cook’s death was a judgement on the navigator’s impiety, the verdict of a jealous Providence. The volumes, Cowper informed one correspondent, furnished him not only with entertainment but with ‘much matter of philosophical speculation’. And, as it proved, they supplied him with material for the ‘new production’ on which he was then working, his long reflective poem The Task.24

In Book I Cowper presents in succinct terms the debate between ‘nature’ and ‘civilization’ which, in one form or another, runs through so much of the literature inspired by Pacific discovery. His own sympathies, dictated both by temperament and belief, lay not with some supposedly idyllic state conjured up by deluded theorists but with the ordered and established society he knew,

Where man, by nature fierce, has laid aside

His fierceness, having learnt, though slow to learn,

The manners and the arts of civil life.

Against this civilized standard he measures the plight of men living in ‘remote / And barb’rous climes’ — not only the ‘shiv’ring natives of the north’ and the ‘rangers of the western world’ where it thrusts ‘Towards th’Antarctic’ but also the denizens of happier regions:

Ev’n the favor’d isles

So lately found, although the constant sun

Cheer all their seasons with a grateful smile,

Can boast but little virtue; and inert

Through plenty, lose in morals, what they gain

In manners, victims of luxurious ease.

In words that hardly square with the sentiments expressed in his correspondence Cowper deplores the cultural poverty of the Pacific islanders, cut off in their isolation from everything that gives civilized life its motive force and meaning:

These therefore I can pity, placed remote

From all that science traces, art invents,

Or inspiration teaches; and inclosed In boundless oceans ….25

Ceasing to generalize, Cowper turns to address the islander who has figured so largely in the narrative of Cook’s last expedition and the readings of his own small circle:

But far beyond the rest, and with most cause

Thee, gentle savage! whom no love of thee

Or thine, but curiosity perhaps,

Or else vain glory, prompted us to draw

Forth from thy native bow’rs.…

That episode is over, the ‘dream is past’, and Omai has returned to his native surroundings but perhaps, the poet speculates (echoing the valedictory reflections of Mr. King), he is no longer content with his former companions and old manner of life:

And having seen our state,

Our palaces, our ladies, and our pomp

Of equipage, our gardens, and our sports,

And heard our music; are thy simple friends,

Thy simple fare, and all thy plain delights

As dear to thee as once? And have thy joys

Lost nothing by comparison with ours?

The questions are rhetorical; Cowper supplies an answer which ranges him with Forster rather than Wales in the debate on Omai’s treatment by his English patrons:

Rude as thou art (for we return’d thee rude

And ignorant, except of outward show)

I cannot think thee yet so dull of heart

And spiritless, as never to regret

Sweets tasted here, and left as soon as known.

Expanding this theme, Cowper pictures the sorrowing native as he strays on the beach, asking the ‘surge’ if it has washed the distant shore of England. Next he sees the young patriot weeping ‘honest tears’, saddened because no power of his can raise his country from its ‘forlorn and abject state’. Fancy finally discloses Omai on a mountain top,

with eager eye

Exploring far and wide the wat’ry waste

For sight of ship from England. Ev’ry speck

Seen in the dim horizon, turns thee pale

With conflict of contending hopes and fears.26

With his melancholy musings and moralizings Cowper had created an enduring literary portrait of Omai but not the one most widely translated and read. That distinction must probably go to a small work first issued by an Oxford printer in the same year as The Task and attributed to a German refugee Rudolf Erich Raspe. In full flight from his creditors, this harassed and somewhat disreputable man of letters reached England in the autumn of 1775 when Omai was still in the country and, as a result of Cook’s return from his second voyage, again figured in the news. So a decade later when putting together a catch-penny trifle, Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels, it was not wholly surprising that he should introduce a passing reference to ‘the Island of Otaheité, mentioned by Captain Cook as the place from whence they brought Omai’. Those names were again topical in 1785 and served to fill a line or so in a hurried compilation.27

Omai’s part in the unexpectedly popular concoction of tall stories was slightly enlarged when some unknown hack was commissioned to prepare a second collection in 1792. The so-called Sequel to the Adventures of Baron Munchausen was a more pretentious work than the original, drawing heavily on literary sources and facetiously dedicated to James Bruce of Abyssinian fame. In one episode Munchausen, accompanied by Gog and Magog, Lord Whittington, Don Quixote, and other members of his entourage, flies to the South Seas in pursuit of Wauwau, the mythical bird from the kingdom of Prester John. He reaches Tahiti where he meets ‘his old acquaintance Omai, who had been in England with the great navigator, Cook’. Omai, he is glad to find, has ‘established Sunday schools over all the islands’. Questioned about Europe and his voyage to England, the unhappy man replies with a flat rendering of the mournful sentiments expressed by Cowper:

‘Ah!’ he said, most emphatically, ‘the English, the cruel English, to murder me with goodness, and refine upon my torture — took me to Europe, and showed me the court of England, the delicacy of exquisite life: they showed me gods, and showed me heaven, as if on purpose to make me feel the loss of them.’

Omai, commanding ‘the chiefest warriors of the islands’, now joins forces with the Baron and his party. He and his fleet of canoes equipped with fighting stages are last seen making for the Isthmus of Darien.28

In the interval between the two editions of Baron Munchausen the putative founder of Polynesian Sunday schools had again served the purposes of social satire. The anonymous author-editor of The Loiterer, an Oxford periodical, announced in July 1789 the discovery of ‘a very great literary Curiosity’, the journal kept by Omai during his visit to Europe. The original, a vast work in three volumes, he promised to deposit in the archives of the Royal Society but before doing so wished to entertain his readers with specimens of the islander’s observations. First in scientific importance is Omai’s theory that many ages ago a large war canoe of his country with some fishing boats were forced out to sea and so peopled the rest of the world. The difference in colour between Europeans and himself he explains by the coldness of their climate which has caused the human species to degenerate, making them less vigorous and ‘of a pale, meagre, sickly, disagreeable complexion’. As proof of his claim for the Polynesian origin of mankind, he cites the similarity between certain words in his own language and others in English. He has learned, for example, that the chiefs or great men of ‘Pretane’ were formerly (though very seldom now) called ‘Heroes’ which is of course the term ‘Erys’ applied to chiefs in Tahiti. There follows a gibe at the expense of Sandwich. Another variant of ‘Ery’, Omai discovers, is ‘Earl’, a title borne by ‘the King of the Ships’ who, being asked by the visitor to show his scars as proof of valour, had to admit that ‘he had never received any Wounds, but in the Wars of Venus.’29

Some British customs, Omai notes, resemble those of the South Seas while others are unique. The inhabitants are often ‘tataowed’, and he himself had to submit to the operation at the hands of ‘the most famous Tataower in the Country’ (i.e. Baron Dimsdale). From the highest to the lowest they are also addicted to thieving, for the doors and windows of their houses are fastened every night with locks, bolts, and bars of the most intricate construction. These are to prevent external robbers entering, but in addition every room, closet, and box inside a house must be locked; which goes to show that husbands hardly dare to trust their wives and children, masters their servants, or servants their masters. Not only are they ‘downright Thieves’ but also ‘absolute Cannibals’, a fact Omai never suspected until one day, while passing through a crowded market, he saw nearly twenty men slaughtered and a woman first strangled and then roasted, ‘much after the same manner as they do Pigs in Otaheite.’ Following the body of one man, he saw it taken to a large house where it was stripped naked, laid on a table before a great crowd, and cut up by a cook dressed in apron and sleeves. He himself was so shocked by the sight that he ran off, leaving the others to finish their ‘horrid Banquet’. Despite such barbarity, Omai acknowledges one virtue — ‘the wonderful Love and Affection, which these people entertain for their King; far exceeding any thing in his own Country.’ It is usual, he says, for everyone to collect little round pieces of metal bearing the King’s image, particularly the yellow ones. Veneration for these images is so great that at first he thought they must be gods but later discovered that an even greater value was placed on slips of paper marked with a female likeness, apparently the Queen’s. As the editor reports:

He was unable to find out what use this thin paper could possibly be of; and what was to him still more astonishing, notwithstanding the great value which every Body put upon it, yet they strangled, without mercy or exception, almost every person that was ingenious enough to make it. In short, he adds, in many things it is absolutely impossible to assign any reason whatever for the actions of this extraordinary People.…30

Meanwhile, in belated fulfilment of a proposal once aired by David Garrick, Omai had made his début on the English stage. It was not, however, as Garrick had suggested, in the guise of an ‘Arlequin Sauvage’ to ridicule the follies and fashions of the time, but as a figure second only in heroic stature to his martyred commander. Some time in 1785 the proprietors of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, casting about for a subject on which to base their annual pantomime, hit upon a highly topical theme, Cook’s last voyage, of which the official account had been published in the previous year. Once the decision was made, tried theatrical journeymen were entrusted with the production. The playwright John O’Keeffe received £100 to write the book and it was he, apparently, who chose to centre the piece on Cook’s exotic companion. For the same fee the continental-born Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg R.A., long domiciled in England, designed costumes and scenery, while the theatre’s resident composer, William Shield, was responsible for the music. All three men necessarily worked in collaboration and in their efforts to secure verisimilitude O’Keeffe and de Loutherbourg consulted veterans of the expedition, James Webber in particular. As preparations went forward, interest mounted in artistic and theatrical circles. It was rumoured that both Gainsborough and Cipriani might contribute their talents to the spectacle, but in the end de Loutherbourg’s designs were carried out by a group of lesser artists led by the Revd. William Peters R.A., Chaplain to the Royal Academy. On 20 December 1785 the first performance of ‘OMAI; Or, A Trip Round the World’ was advertised for that night, following ‘the Tragedy of Jane Shore’. There was no mention of the author’s name, but Mr. Shield was billed as composer and Mr. Loutherbourg given full credit for designing and inventing ‘The Pantomime, and the whole of the Scenery, Machinery, Dresses, &c. &c.’ In anticipation of a heavy demand for places, patrons were warned: ‘Nothing under Full Price will be taken.’31

61 Playbill for first performance of Omai

62-65 De Loutherbourg’s drawings for the costumes of Omai: Otoo; Oberea; Towha; Man of New Zealand

Garrick had not lived to see his original idea shorn of its satirical purpose and presented with all the resources of his old theatre. Predeceasing both Cook and Omai, he had been interred in Westminster Abbey nearly seven years before. But Sir Joshua Reynolds was in the crowded house, prominently seated in the orchestra, perhaps in deference to his fame, perhaps on account of his defective sight and hearing. A memorable evening opened with Jane Shore which, the Morning Chronicle reported the next day in a lengthy review, was tolerated rather than enjoyed:

Though the Play was upon the whole far from ill-performed, the audience during its representation expressed great impatience for the Pantomime, of which vague report had said enough, to raise very great expectation. At length the curtain drew up, and before it dropped, all present were convinced, that not a syllable too much had been said in favour of Omai. A spectacle abounding with such a variety of uncommonly beautiful scenery never before was seen from the stage of a theatre; nor was there ever, considered altogether, a more rich treat for the lovers of musick, Mr. Shield having been remarkably successful in the composition of the airs, recitatives, and accompanyments.

Amid a further welter of superlatives the only hints of adverse criticism were directed at the plot where the ‘business’ was rather slender and the incidents few. But in the first part, the writer conceded, they were ‘light and laughable’ and in the second merely ‘calculated to serve as a necessary connection of the changes of scenery; for the exhibition of which the whole of the piece has been obviously imagined and contrived’. It should, he summed up, ‘be considered as the stage edition of Captain Cook’s voyage to Otaheite, Kamschatka the Friendly Islands, &c. &c. and a most beautiful edition it is.’32

The pantomime, or at least O’Keeffe’s contribution, seems in reality to have had closer affinities with Munchausen’s Marvellous Travels than with Cook and King’s sober narrative. The plot, as recorded in newspaper summaries, was a fanciful mélange in which stock figures of European comedy mingle with fictitious characters, patriotic abstractions with personages drawn from the official volumes and freely adapted to histrionic requirements. Omai, elevated to regal status as the son of Otoo, is transported from his ancestral domain by Britannia and reaches England. There he worsts his Spanish rival Don Struttolando, wins the hand of Londina, and carries her back to the South Seas, touching at many places visited by Cook and so supplying pretexts for the display of de Loutherbourg’s scenic invention. The minor characters include Harlequin, Colombine, and Clown who are servants of the three principals; Towha is described as ‘the Guardian Genius of Omai’s ancestors’; Odiddy (here termed Oediddee) is another of Omai’s rivals, ‘Pretender to the throne’ of Tahiti; and in a further sinister metamorphosis Oberea becomes ‘Regent and Protectress of Oediddee, an enchantress’. Proceedings reach their triumphant conclusion in the scene of Omai’s coronation and marriage which takes place ‘in the great bay of Otaheite’,

with a view of ships at anchor, and a royal palace in front, and the people ready to receive and crown their King. A fine view offers itself of all the boats of the islands entering the bay with Ambassadors from all the foreign powers bringing presents, and a procession ensues, and salutes Omai, as the ally of Britain, and compliments him with an English sword. This is succeeded by dancing, wrestling, boxing, &c. The Clown wins one of the dancers by the present of a nail. Harlequin and Colombine, Omai and Londina, are united, and the entertainment concludes with an apotheosis of Captain Cook, crowned by Fame and Britannia….

Reynolds was said to have expressed the utmost satisfaction with the landscape scenes but was less complimentary about the apotheosis, painted by Mr. Peters from de Loutherbourg’s design. Perhaps, it was surmised, he disapproved of the Academy’s chaplain lending himself to an enterprise of this kind.33

Whatever the nature of Sir Joshua’s reservations, they do not seem to have troubled many patrons of Covent Garden. The tribute to Cook was one of the most celebrated features of the performance, sharing in the applause that nightly greeted scenic effects and music. If there was any weakness it was in the ‘comick business’, but efforts were soon made to improve this part of the production and by Christmas Eve it was reported that the humorous scenes now excited ‘the most extravagant testimonies of delight’. Special mention was made of a new character, introduced the previous night (and evidently based on the historical Omai), who had accompanied the hero on his travels and ‘most whimsically and pantomimicaly dressed himself in a piece of the habit of each country he had met with’. This and similar measures ensured the success of the spectacle which in its first season ran for fifty performances, one by royal command, and held the stage until 1788. In one of his earlier manifestations, as the scourge of English society, perhaps Omai himself made the appropriate comment:

The stage, once rich in stores of genuine wit,

When Nature dictated what SHAKESPEARE writ;

When GARRICK’S pow’rs that Nature could improve,

And rouse the soul to rage, or melt to love;

Now in vile farce and pantomime displays

The vicious taste of these refining days.…34

SOME SUCH VIEW was indeed expressed by a critical observer of contemporary England. In the autumn of 1785 the young French poet Louis de Fontanes reached London on an extended visit. He had come with the idea of publishing a series of letters that would bring English society up to date with the latest intellectual movements in his own country but, receiving no encouragement, soon abandoned the plan. Instead, he contented himself with sending back to his friend Joseph Joubert impressions of life in the capital with any information he could pick up about Cook for use in the panegyric Joubert, a devoted student of the explorer, was then writing. What he learned was little enough and that often far from complimentary. People who had known the great man in private life spoke of his forbidding manner, an opinion confirmed by stories of his disputes with the Forsters during the second expedition. Cook was accused of obstinacy, even of jealousy; on the other hand, de Fontanes conceded, the younger Forster had shown bitterness and vanity in his own conduct. The ‘respectable’ Banks was out of town when the Frenchman arrived and on his return disclosed nothing of importance concerning Cook. Nor would he comment on the Forsters, though it was apparent from his silence that he took the captain’s side in the controversy. Altogether, the poet assured his friend, Forster had put into his narrative everything about the voyage that could interest anyone of sensibility and imagination. As for Joubert’s hero, he enjoyed far less renown among his own people than he did in France, for the English ranked Cook no higher than their other leading navigators. They had not yet raised a monument to him and the only tributes to his memory were mementoes of his voyages and a portrait displayed in the ‘Sandwich room’ of Sir Ashton Levert’s museum.35

De Fontanes had some pretensions as a connoisseur and critic of art. Early in his stay he called on Sir Joshua Reynolds at his studio and saw the ‘original’ portrait of Omai, apparently known to him before through an engraved copy. At the time he expressed no opinion of the work but later, while acknowledging some merit in the ‘chevalier’s’ portraiture, found it much inferior to Romney’s. On the subject of Reynolds’s history painting he was extremely scathing: ‘The Death of Dido’ he thought unworthy of the most mediocre dauber. The more he saw of England, he confessed, the more he became convinced that it was a nation given up to trade and money rather than to pleasure or the fine arts. The age of Charles II and Queen Anne had polished Court manners a little, but that was now past, leaving the mass of people as barbarous as ever. It was their ferocity and stupidity, de Fontanes held, that set the tone for public shows and entertainments. What did they applaud at the theatre? Not those pieces by Shakespeare worthy of esteem but usually the most tasteless and ridiculous — and he instanced the much applauded Measure for Measure, a play that could only have been written for the London taverns. So he was hardly in a receptive mood when late in January 1786 he went to see Omai still playing to great crowds at Covent Garden. The subject was charming, he remarked, and the genius of Cook should have inspired those responsible. As it proved:

Ah well! they have made Harlequin Omai’s servant. They portray the Tahitian disembarking at Portsmouth, chased by customs officers and policemen in a large carriage. The scene changes. The young islander is returning to his homeland. They are waiting for something: it is a sailor who, intending to pick up his coat from the coach where he left it, finds there a huge crab which devours his entire head, etc.

The scenery, he added, was taken from designs by the famous Loutherbourg. It was very beautiful but only made one realize more strongly the absurdity of the rest.36 How much better they ordered such matters in France was the implied comment.

Not only better but on a suitably monumental scale, as Guillaume-André-René Baston, professor of theology at Rouen and a canon of its cathedral, was soon to demonstrate. The abbé had succeeded in combining his professorial and clerical duties with a close study of the South Seas and in 1790 published the results of his wide-ranging research. Had he rendered them in conventional expository form, he would probably have joined de Brosses and Prévost in the distinguished line of French Pacific scholars. As it was, he chose to present his conclusions in fictional guise and, not altogether deservedly, they passed into oblivion. Issued anonymously in four bulky volumes, the novel was entitled Narrations d’Omai, Insulaire de la Mer du Sud, Ami et Compagnon de Voyage du Capitaine Cook. A frontispiece displayed an oval portrait of Omai, based on the engraving after Hodges and ornamented by symbolic objects — a cornucopia, a quiver of arrows, quills, paper, a pile of books. Beneath it was a crude landscape, apparently of a tropical beach, showing the prow of a ship and grazing horses. The work purported to be Omai’s autobiography, written in his native tongue and entrusted to its translator, Monsieur K***, who on his death-bed at the Cape of Good Hope handed the manuscript over to his old schoolfellow and shipmate Captain L.A.B. The memoirs were divided into twenty-five ‘Narrations’, each dedicated to a leading character and arranged in chronological sequence.37

Throughout his recorded career, observers of Omai had speculated on the possibilities that lay open to him when he again reached home. Would he become the Czar Peter the Great of his nation? To Lichtenberg it seemed unlikely. Rickman, on the other hand, thought he might rise superior to all the chiefs in the surrounding islands and in time become lord of them all. Cook pitched his expectations lower but was fairly confident his protégé would tend the plants and livestock left with him and so transform Huahine into a storehouse of European supplies. Paradoxically it was his sternest critic who saw in Omai’s travels the greatest potentialities for good. If only he had fallen into the right hands, Forster lamented, he might have become the law-giver and benefactor of his people. He might have taught them new crafts and industries, helped them to explore and use their resources, introduced them to the ethics and beliefs of Christianity. Suppose, then, the returned voyager had done all these things and more. Suppose he had preserved what was best in island life while abolishing its evils. Suppose he had been wise, industrious, modest, humane, far-seeing. Suppose, in short, he had possessed all the qualities he so conspicuously lacked in the eyes of his detractors. Such was Omai as Baston conceived him, such the hero he lovingly evoked in the course of his elaborate fantasy.

The early pages skilfully blend biographical details with an outline of recent Pacific history. The narrator summarizes each expedition and, with a noticeable bias in favour of the French, characterizes their leaders — the cruel Wallis, the well-beloved Bougainville, the brave but not wholly blameless Cook. There is passing mention of ‘Aoutourou’ who had the ‘incredible audacity’ to embark with Bougainville but who, alas, did not survive. Omai himself, as he relates the story, appears in a highly sympathetic light. He is of superior but not royal birth, the son of a Raiatean landowner slain with his own hands by ‘Opoony’, the tyrant of Borabora. While languishing in exile, he loses his mother and is saved from despair only by the hope of joining ‘Tupia’ to redress their wrongs and destroy the usurper. During his countryman’s absence on the Endeavour the hapless youth figures in a familiar tableau as he paces the shore, transforming detached clouds into imaginary ships. At length two vessels do appear but without Tupia who, Omai learns, is also dead. ‘Ah!’ he exclaims, ‘who then will free my native land? Who will take revenge on Opoony?’ None other than Omai himself. In pursuance of his sacred mission he joins the Adventure and so begins the travels that fill most of the first volume. His opening narration he inscribes to Furneaux but for whose ‘noble obstinacy’ (in opposing Cook’s prejudices), he gratefully acknowledges, he would have ended his life poor and ignorant or clubbed to death in battle.38

As he boards the ship at Huahine, Omai breaks off the story to consider the charges brought against him by Cook and Forster, first quoting the captain’s references to his lowly status and dark colour. It is hardly surprising, he retorts, that a man who was exiled from his country, deprived of possessions, and saved from death by a miracle should not hold a high social position. Going on to refute the suggestion that his dusky countenance implies low birth, he points out that in England he met noble lords whose appearance was far from inviting, whereas in the lowest classes he saw complexions as fair as the rose, as white as the lily. General rules, he observes, are not without exceptions. Furthermore, his wanderings, his misfortunes, the constant necessity to earn a subsistence by fishing accentuated the natural darkness of his skin. Even Cook’s compliments are not entirely to the young democrat’s taste. The captain, he remarks, has commended him for his pride in avoiding the society of the low-born while he lived in England; but he scarcely knows whether to take this as praise or blame. He cultivated people of quality, he explains, not through ‘pride’ but simply because they could give him more help than their social inferiors in carrying out his plans.39

From Cook he turns to a less generous chronicler, George Forster. This critic again casts doubt on his status by asserting that on the Adventure he preferred the company of armourer and sailors to the captain’s. True, Omai admits, at that time he considered the humblest European superior to his own chiefs. In addition, he courted the armourer because European weapons were among the things that interested him most; and he mixed with the men because he could question them freely and found their replies within his comprehension. As for the charges that he was stupid, that his tastes were childish, that his time in England was spent in frivolous pursuits — these calumnies he indignantly denies. Could a stupid man, he asks, have mingled with ease in the highest social circles or mastered the game of chess? Forster again derides his acquisition of a portable organ, an electrical machine, a suit of armour; but in his country, Omai points out, such things were worth more than all the guineas in the three kingdoms. Even more wounding are the comparisons Forster makes with Tupia’s genius and superior talents. Omai freely acknowledges his compatriot’s merit but does not concede that it infinitely surpasses his own. The proof, he asserts, will be found in the course of his narrative, and he goes on to deny Forster’s monstrous charge that he threatened to cut off Cook’s supplies unless the captain helped with his plans for revenge. In sum, he concludes, Forster has treated him far less kindly than Cook. And the reason? Merely because the naturalist resented the fact that while Omai was taken to England his own nominee was refused a passage.40

After this self-justifying digression, Omai returns to the account of his voyage on the Adventure, first recording his chagrin when another islander — a Boraboran and kinsman of Opoony at that! — joins the expedition at Raiatea. To his relief it appears that Odiddy is to voyage only in the Pacific and will not therefore be his rival in the quest for British wealth and weapons. He briefly describes subsequent events — the visit to the Friendly Isles, the disappearance of the Resolution, the tragic episode in Queen Charlotte Sound, and the passage to England. Though his appearance in London created a sensation, it was, he asserts, nothing to what he felt: ‘Ye gods! how many things astonished me! What a host of oddities, of inconsistencies, of contradictions!’ He acknowledges the graciousness of the King in granting him a private audience and pays his respects to his zealous protectors and honoured friends, Mr. Banks, Dr. Solander, and ‘Mylord’ Sandwich (who is accorded the special tribute of a dedication). Two years passed, he writes, during which, in spite of Forster, he did not neglect to gather useful knowledge. Pleasure also occupied part of his time, for he was young and often tempted. But, again in reply to his detractor, he never resorted to the ladies in the Strand; he was too well warned, had too much self-regard, too much respect for his friends to degrade himself with such infamous creatures. He left on the Resolution in July 1776.41

The return voyage, largely based on published sources, may be quickly summarized, for it is not here that Baston displayed his originality. Omai tells of the passage to New Zealand where the two boys enter his service; he modestly plays down his own part in the perilous day spent on Atiu; and he dwells at length on their adventures in the Friendly Isles, giving a sympathetic picture of his patron Feenough. Of their weeks in Tahiti he says little and of his recorded indiscretions nothing. At Vaitepiha Bay he greets his relatives while Cook learns that the ‘celebrated’ Oberea is dead and listens incredulously as the prophet Etary foretells that he is to die at the hands of men who will pay him divine honours. Reaching Matavai, Omai relates, he does obeisance to Otoo and again meets Odiddy of whom he is no longer jealous since his former rival’s travels have been so limited compared with his own. He is mildly critical of the commander’s actions on Moorea but conceives a dislike for the ill-favoured Maheine and continues with an account of subsequent events at Huahine: Cook’s decision that he must settle here and not at Raiatea; his meeting with Tareederia, the young King’s widowed mother (known as ‘Nowa’), and the assembly of local chiefs; then the granting of his estate, followed by the building of a house and the transfer of animals and treasure to his property. On the eve of sailing, Cook in a Polonius-like oration counsels prudence in his charge’s dealings with Opoony and advises him to marry: a good wife, he says, will make him cherish life more than vengeance. As for himself, the captain ends, he is overcome with forebodings and feels it unlikely they will again meet. At the moment of parting, Omai recalls, he bathed his protector’s face with ‘a torrent of tears’ and returned to the shore overcome by ‘a frenzy of suffering’.42

With Cook’s departure towards the end of Volume I, Baston was wholly released from the trammels of recorded fact to develop his heroic theme as he pleased. In spite of his grief, the fictional Omai loses no time before organizing his domestic affairs and instituting reforms. One of his sisters, ‘Zée’ by name, having joined the household, he insists that she sit with the menfolk at table, for the ‘ridiculous’ custom of women eating separately is, he holds, injurious to ‘the comelier half of human kind’. Guided by an engraving in his collection and aided by his retainers, he now lays out his estate, designs formal gardens, digs irrigation channels, and extends the vegetable plots sown by Cook. The products, popularly known as ‘manger de Cook’ or ‘manger d’Omai’, surpass all expectations, transforming Huahine into a cornucopia of supplies. Encouraged by this success, Omai ventures on a bolder experiment. Using one of his toys as a model, he sets out to fashion a plough with the help of the New Zealander Tiarooa who shows some inventive talent. The result, he admits, is faulty but, given their limited means and lack of experience, a masterpiece. At a great gathering attended by the King, his mother Nowa, with other notabilities from this and the neighbouring islands, he yokes his horses to the plough and demonstrates its use. Others follow his example and the men of Huahine soon become expert tillers of the soil. With his eye on their womenfolk, he persuades Otoo to transfer Cook’s cattle to his own care, whereupon he teaches Nowa, Zee, and their humbler sisters how to make butter and cheese, domestic arts they quickly master. His next achievement is designed to add to the amenities of island life. He builds a carriage — not, he again acknowledges, as elegant as that of an English ‘Mylord’ but well enough fashioned and embellished. As a token of regard, he presents the vehicle to Nowa.43

His civilizing mission thus begun, Omai proceeds to discharge the sacred obligations he owes to his dead father and oppressed countrymen. A chance meeting with the exiled King of Raiatea spurs him on to dislodge the Boraborans from his native island. He throws down the gauntlet with a daring raid on Borabora itself where by a ruse of the quick-witted Coaa he captures Opoony’s small flock of sheep, thus ensuring Huahine’s monopoly of the precious animals. Next, leading a force equipped with English weapons and drilled in English tactics, he invades Raiatea and defeats the usurpers. Coaa, alas, is one of the casualties, but Tiarooa proves his heroic mettle and soon holds the post of Omai’s chief lieutenant. Opoony marshals his subjects to crush the impudent upstart, only to be overcome in a great naval battle and carried off to Huahine. After a series of military triumphs, Omai controls the whole of the Society Group, while his friend King Otoo is firmly established at Tahiti. In a final campaign he joins with his allies to crush the villainous Maheine and restore the rightful monarch to the throne of Moorea. His victories are won, however, without recourse to traditional savagery. Omai forbids unnecessary bloodshed, frees his prisoners, and, despite opposition from his vengeful countrymen, refuses to execute Opoony, sentencing him instead to honourable exile. Nor will he himself assume the deposed tyrant’s mantle. The grateful inhabitants repeatedly offer him the crown of some liberated territory, but each time he declines the honour, preferring to nominate such trusted favourites as Tiarooa. He chooses to remain at Huahine with Nowa, ‘the best of women’, whom he has admired from the first and whom after a chaste courtship he has married.44

Omai the Civilizer, the Conqueror, the King-maker, now assumes the role of Law-giver. Summoning the rulers of neighbouring kingdoms, he persuades them to adopt a constitution for a new state to be known as the Confederation of the United Islands. It will have two chambers, one of sovereigns and chiefs, the other of deputies representing the lower orders. In addition, there will be the Supreme Council, a sort of cabinet in permanent session, led by a president who will also be viceroy of the capital and commander of its garrison. To avoid jealousy among rival candidates and ensure the president’s impartiality, a foreigner is chosen to hold the high office, the New Zealander Tiarooa. Under these auspices and profiting by his European experience, Omai introduces reforms covering every aspect of island life. As a beginning he persuades the members of the Supreme Council, on behalf of their people, to join together with indissoluble ties of brotherhood and abolish war. All quarrels will in future be submitted to the Supreme Council for arbitration. They then proceed to forbid such practices as public prostitution in honour of the gods, human sacrifice, and infanticide. The ancient custom of circumcision, which Omai now considers unnecessary, is discouraged but not forbidden.45

Omai and his colleagues devote special attention to the affairs and status of women. Like Zee, they will no longer be segregated at table and, following the English fashion, will occupy the place of honour at festivals and all entertainments. At the time of marriage the possessions of wife and husband will be pooled and, should one partner die, the survivor will retain half the estate and their offspring the remainder. Children will inherit the property of their parents equally, with no distinction between boys and girls, older and younger, legitimate progeny and those born out of wedlock. But Omai is far from encouraging sexual licence and introduces measures designed to curb the notorious immorality of his native islands. Prostitutes must declare their occupation to the Chief Magistrate and wear a special dress distinguishing them from ‘honest’ women. Any chief resorting to a prostitute will forfeit all his inherited rights which can be restored only by a decree of the Supreme Council. The problem of venereal disease, introduced by Europeans, is disposed of summarily. Those suffering from the malady will be transported to uninhabited islands, men and women separately, to undergo treatment until certified as cured. Further, to prevent a recurrence of the disease, any women who allow themselves to be seduced by visiting mariners will be banished. Other evils are dealt with in a penal code of the utmost simplicity. Little distinction is made between sins and social crimes which are reduced to four — impiety, homicide, adultery, theft. Penalties range from death by clubbing (for murder and adultery) to banishment and the bastinado. ‘Be warned, Europeans,’ Omai advises future navigators, ‘if henceforth you take without permission our grass, our wood, our water, our cloth, you will not carry your ears back to Europe. It is from you we have learned this punishment for theft.’46