In this chapter, we’ll look at informational texts and then guide you through active reading strategies to help you crack the questions.

Think about it—what do you spend more time reading and listening to in a typical day? News reports, advertisements, political speeches and similar nonfiction material, or literary stories? Nonfiction, right? Life is filled with informational material that you need to deal with in some way (even if only to decide to tune it out), so that’s what the GED® test emphasizes. In fact, 75 percent of the six to eight reading passages are classified as informational.

The critical thinking and active reading skills you’ll gain in preparing for the reading passages will help you sort through the informational material that fills your life outside the test, too. With those skills, you’ll learn to question, identify flaws in reasoning, recognize a legitimate argument when you see it, and in short, become a wiser, more discriminating consumer of information.

How about an article explaining how wind turbines work? Or a speech from a company’s president outlining the great opportunities for growth—and profit—that lie ahead? Or perhaps the results of a study on which foods are the best choices for good cholesterol?

Since the GED® test aims to measure readiness for career and college, subjects can be drawn from both the workplace and the academic worlds. That’s a pretty big target, and indeed, the range of real-world subjects is broad.

From the workplace, you could see letters or ads aimed at customers, corporate policy statements, executive speeches, or community announcements about events the company is sponsoring. From the academic world, subjects focus on science (especially energy, human health, and living systems) and on social studies. Those social studies subjects are built around what’s called The Great American Conversation, which includes documents created when the United States was founded as well as later discussions about American citizenship and culture. There, you might see editorials or essays, speeches, biographies, letters written by famous people, government documents, court decisions, or contemporary articles.

Readings could be in the public domain, which means they’re old enough that any copyright has expired and they sport the long sentences and flowery language characteristic of earlier styles of writing. The older writing style means that you’ll have to apply a fair amount of critical thinking in order to get what the author is saying.

Try this Great American Conversation excerpt, for instance:

Excerpt from A Defense of the Constitution of Government of the United States of America, by John Adams, 1786

If we should extend our candor so far as to own, that the majority of men are generally under the dominion of benevolence and good intentions, yet, it must be confessed, that a vast majority frequently transgress; and, what is more directly to the point, not only a majority, but almost all, confine their benevolence to their families, relations, personal friends, parish, village, city, county, province, and that very few, indeed, extend it impartially to the whole community.

That’s how people wrote back in 1786. Once you break this long sentence into pieces, skip over the parts that don’t make a direct statement, and substitute simpler words in the parts that do, you end up with a pretty straightforward summary: “Even if we say that most men mean well, we have to admit that almost all of them limit their kindness to the people around them.” The context should help you take a good guess at the meaning of words that may not be familiar, such as “candor,” “benevolence,” and “transgress,” as well as the unusual meaning of “own.” After you’ve tossed out the extra words and phrases, though, the only one of these words really needed for your straightforward summary is “benevolence,” and the pairing of that word with “good intentions” makes its meaning fairly obvious.

What you won’t see among the informational readings are objective, neutral passages that simply describe or explain something, such as you’d find in an encyclopedia or a product instruction manual. The GED® test’s informational passages are more complex than that. They will have a “voice”—an author with a specific point of view and purpose. The author might be trying to persuade readers to boycott a particular company, for instance, or the author may be giving a speech criticizing a new government policy. These passages will draw on your analytical and critical thinking skills to discover not only the author’s purpose but also what techniques the author uses to support a position, what assumptions the author has made, and whether the argument is logical and sound.

First, keep your mind actively engaged with the passage and second, think critically instead of simply accepting the passage at face value.

While you may not have time for full-blown active reading strategies, you’ll still need to use them (and your note boards) to some extent in order to seize control of the passage and make it give you what you need, instead of letting the passage run the show. You’re on a mission—you have questions to answer in a limited amount of time—and passively absorbing (or worse, skimming through) the passage will only force you to keep going back and rereading it.

How do you read actively? In a nutshell, keep asking questions and looking for specific things as you go through the passage. Hunt for the flaws and gaps that weaken an argument; recognize the strong support and smooth organization that strengthen it. When you read each section or paragraph, summarize quickly, in your own words, what it’s saying.

You’ll need to do a lot of this in your head—that’s about all you have time for—but you can scribble a couple of words to capture a main idea, or a one-word-per-line list of what happens first, second, and so on. You won’t need to get far into the passage before you’ll know what’s important. For many people, just writing something down helps them remember, even if they don’t look at their note board again, and searching for words that would be important enough to jot down can force you into active reading mode. You can try using this technique with the drills and practice tests in this book to see how much it helps you.

Questions to Ask As You Read Informational Passages

What does the author want readers to do or to think after they read this?

Who is the intended audience?

What is the author’s main point?

How, and how well, is the main point supported?

Does the author have an obvious bias or point of view?

What assumptions does the author make?

What is the author’s tone?

Is the author’s reasoning logical?

Is the piece complete, or does it leave unanswered questions?

Are the language and sentence structure appropriate for the audience and for the time in which the author was writing?

Answering those questions as you read will put you in command of just about any informational piece, whether it’s from a workplace or an academic context. Then you can start cracking the questions.

Let’s go through a couple of examples that will help you practice reading actively and approaching the different question tasks.

The following CD review appeared in the pages of Soul Blues magazine

1 Even by genre standards, Texas bluesman Sam “Lightnin” Hopkins released a stupefying amount of material during his lengthy career. As a guitar player, he was never what one would call a perfectionist: few of his recordings are free of off-notes or mis-fretted chords, and he had no compunction about putting out version after version of the same song, either under the same or different titles.

2 For such reasons, many fans feel that Hopkins is better served by “Best of” compilations than by individual albums. But how is one to choose which tracks to include on a compilation CD, when there is such a surfeit of material? How can one select the best, say, “Mojo Hand,” when there are 30-odd recordings of it floating around? Seemingly every time he sat down to record, he’d do another run through “Mojo Hand.” Every time he recorded the song he played it a little differently: each has its recommendations, each its shortcomings. And every one of those takes has been released at some point over the years.

3 Since so many versions of the song were released, none sold appreciably better than the others—making “popular acclaim” a moot point. No particular recording can be called a “Greatest Hit,” even though the song itself is probably his best-known composition.

4 So, when it’s time to put out another “Lightnin” Hopkins compilation CD, that means it’s time to decide upon a “Mojo Hand” to include on it.

5 It would seem that all the intrepid compiler can do is choose one version of “Mojo Hand” that is just as good as (although admittedly no better than) many others…and then do the same for “Katie Mae,” and again for “Lightnin’s Boogie,” and on and on…thus rendering any purported “Best of” album less representative of Sam “Lightnin” Hopkins than of the person putting it together.

6 So it is with this most recent album: the song titles are there, and a fan finds few surprises among them. But do you need this album? Do you need these particular versions, culled from various sessions spanning five decades? Do you need yet another “Lightnin” Hopkins CD titled—you guessed it—MOJO HAND?

Before we tackle some questions, let’s look at how to read this passage actively by asking yourself questions as you go through it. To train yourself in the active reading techniques you’ll need for the test, note your answer on some scratch paper (or at least think of your answer) before you read the one below the question.

What does the author want readers to do or to think after they read this? The overall impression, by the time you reach the end of the review, is summed up in the question, “do you need this album?” (paragraph 6). The author wants readers to understand that, if they already have a selection of “Lightnin” Hopkins’s huge roster of albums, they probably don’t need this one, too.

Who is the intended audience? You can tell by the casual tone, lack of musical terminology (except for “mis-fretted chords” in paragraph 1), and absence of background information on the singer or the songs mentioned, that the reviewer is writing for people who are probably not professional musicians but who are familiar with Hopkins’s work.

What is the author’s main point? That’s in the references to how many versions of a song Hopkins habitually recorded, and in the conclusion that so many versions make “any purported ‘Best of’ album less representative of Sam ‘Lightnin’ Hopkins than of the person putting it together” (paragraph 5).

How, and how well, is the main point supported? The difficulty of compiling a truly representative “Best of” album is well supported. The author says that Hopkins “had no compunction about putting out version after version of the same song” (paragraph 1) and that “each [version] has its recommendations, each its shortcomings” (paragraph 2). There is no objective yardstick for selecting what to include, leading to subjective decisions by the person making the selections.

Does the author have an obvious bias or point of view? The author clearly thinks Hopkins was sloppy in creating his body of work—“few of his recordings are free of off-notes or mis-fretted chords, and he had no compunction about putting out version after version of the same song” (paragraph 1).

What assumptions does the author make? The lack of background information about the artist and the songs mentioned reveals an assumption that readers are already familiar with Hopkins’s work.

What is the author’s tone? You can tell from opinions such as “never what one would call a perfectionist” (paragraph 1) and “all the intrepid compiler can do is choose one version of ‘Mojo Hand’ that is just as good as (although admittedly no better than) many others” (paragraph 5) that the author is critical of both the singer’s careless approach and the objective of creating a “Best of” compilation.

Is the author’s reasoning logical? Yes; the author builds a logical chain of reasoning from too many versions of a song, with none standing out as superior, to a compilation that relies on the subjective opinions of an unknown compiler and is therefore of questionable value in representing the best of an artist’s work.

Is the piece complete, or does it leave unanswered questions? Since the author places so much weight on the person selecting which version of each song to include, it would be helpful to know who actually made the compilation. Was it someone who had followed Hopkins’s career for a long time? Someone who is well versed in that genre of music?

Are the language and sentence structure appropriate for the audience and for the time in which the author was writing? Yes, the language is appropriate for an educated audience well versed in this genre of music but not professional musicians. The sentence structure is contemporary and varied, making the piece interesting to read.

Now that you’ve got a good sense of what the author is trying to achieve and how he or she went about reaching that destination, let’s look at a few questions. Try to select the answer yourself, using the insight you gained from the active reading questions, before you read the explanation below the choices.

1. The questions in the final paragraph are intended to make the reader

A. wonder if compilation CDs serve any purpose.

B. realize that Hopkins was less talented than many listeners believe.

C. see that this compilation CD may not be a necessary addition to a Hopkins collection.

D. understand that nobody can predict which version of a song will sell the most copies.

Here’s How to Crack It

You got the answer to this structure question (Why is it there?) from the very first active reading question (What does the author want readers to do or to think?) that you asked yourself as you read through the passage. The author wants them to think (C). The last paragraph reinforces the reasons given earlier in the passage: With so many versions of a song, all of about equal value, why would someone need these particular, subjectively chosen versions?

Choice (A) is too broad (the passage is talking only about Hopkins’s work); (B) is inaccurate (Hopkins is described as careless, not untalented); and (D) is beside the point (the compilation is being done from an existing body of work, so no prediction is involved, and it is supposed to include the best, not necessarily the best selling).

2. The writer describes the compiler (paragraph 5) as being

A. misguided.

B. intelligent.

C. artistic.

D. adventurous.

Here’s How to Crack It

This language use question is asking you to figure out the meaning of “intrepid” from the context. You’ve discovered from your active reading that we’re not told anything about the compiler’s credentials for making selections, and that choosing from a long list of roughly equal versions is, at best, a subjective gamble. Process of Elimination gets rid of (A) (the compiler is not following a wrong path by making a compilation, but just has to make a judgment call when doing so) and of (B) and (C) (intelligence and artistic talent wouldn’t help when all of the versions have about the same value). That leaves (D) as the correct answer, and indeed, an adventurous spirit would be useful in taking that subjective gamble with track after track.

3. The author implies that “Katie Mae”

A. exists in multiple versions.

B. is better than “Lightnin’s Boogie.”

C. was recorded after “Mojo Hand.”

D. has been overshadowed by Hopkins’s other songs.

Here’s How to Crack It

At its heart, this is a development question. You know from your active reading that this song isn’t the main focus of the passage. So what is the author saying about it and how does that contribute to the development of the main point? The answer, as always, is right in the passage. “Katie Mae” is yet another instance of having to choose one version “that is just as good as (although admittedly no better than) many others” (paragraph 5). It’s a building block in constructing the main point about any Hopkins compilation representing the compiler, not the singer. So (A) is the only answer that is supported in the passage.

4. The author infers that Lightnin’ Hopkins’s body of musical works

A. is larger than that of any other blues musician.

B. is filled with too many mistakes for any of the recordings to be considered good.

C. resists easy song selection processes.

D. cannot be represented on a compilation CD.

Here’s How to Crack It

This question takes the main point, which you’ve already identified in your active reading questions, and then asks you to take it a step further to figure out what it infers about Hopkins’s work. For this question, you’d follow the main point to (C): the many and roughly equal versions of the same songs make selection difficult, leading to a compilation that is more representative of the person doing the selecting than it is of the singer’s work. The author never says (or infers) (A), (B), or (D); they are all too extreme for the statements made in the passage.

Now that we’ve seen how the active reading questions can help you take control of a passage and answer questions about it, let’s go through an example in which we can focus on the seven question tasks in action.

Killer Clothing Was All the Rage in the 19th Century

Arsenic dresses, mercury hats, and flammable clothing caused a lot of pain.

by Becky Little, National Geographic

1 While sitting at home one afternoon in 1861, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s wife, Fanny, caught fire. Her burns were so severe that she died the next day. According to her obituary, the fire had started when “a match or piece of lighted paper caught her dress.”

2 At the time, this wasn’t a peculiar way to die. In the days when candles, oil lamps, and fireplaces lit and heated American and European homes, women’s wide hoop skirts and flowing cotton and tulle dresses were a fire hazard, unlike men’s tighter-fitting wool clothes.

3 It wasn’t just dresses: Fashion at this time was riddled with dangers. Socks made with aniline dyes inflamed men’s feet and gave garment workers sores and even bladder cancer. Lead makeup damaged women’s wrist nerves so that they couldn’t raise their hands. Celluloid combs, which some women wore in their hair, exploded if they got too hot. In Pittsburgh, a newspaper reported that a man with a celluloid comb lost his life “While Caring for His Long Gray Beard.” In Brooklyn, a comb factory exploded.

4 In fact, some of the most fashionable clothing of the day was made using chemicals that are today considered too toxic to use—and it was the producers of this clothing, rather than the wearers, who suffered most of all.

Mercurial Maladies

5 Many people think that “mad as a hatter” refers to the mental and physical side effects hat-makers endured from using mercury in their craft. Though scholars dispute whether this is actually the origin of the phrase, many hatters did develop mercury poisoning. And even though the phrase has a certain levity to it, and while the Mad Hatter in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was silly and fun, the actual maladies hat-makers suffered were no joke—mercury poisoning was debilitating and deadly.

6 In the 18th and 19th centuries, a lot of men’s felt hats were made using hare and rabbit fur. In order to make this fur stick together to form felt, hatters brushed it with mercury.

7 “It was extremely toxic,” says Alison Matthews David, author of Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present. “Especially if you inhale it. It goes straight to your brain.”

8 One of the first symptoms was neuromotor problems, like trembling. In the hat-making town of Danbury, Connecticut, this was known as the “Danbury shakes.”

9 Then there were the psychological problems. “You would become very shy, very paranoid,” Matthews David says. When medical examiners visited hatters to document their symptoms, hatters “thought they were being observed, and they would throw down their tools and get angry and have outbursts.”

10 Many hatters also developed cardiorespiratory problems, lost their teeth, and died at early ages.

11 Although these effects were documented, many viewed them as the hazards that one had to accept with the job. And besides, the mercury only affected the hatters—not the men who wore the hats, who were protected by the hats’ lining.

12 “There was always kind of a bit of a pushback from the hatters themselves,” Matthews David says of these dangerous working conditions. “But really, honestly, the only thing that made [mercury hat-making] disappear was the fact that men’s hats went out of fashion in the 1960s. That’s really when it dies. It was never banned in Britain.”

Arsenic and Old Lace

13 Arsenic was everywhere in Victorian Britain. Although it was known to be used as a murder weapon, the cheap, natural element was used in candles, curtains, and wallpaper, writes James C. Whorton in The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain Was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play.

14 Because it dyed fabric bright green, arsenic also ended up in dresses, gloves, shoes, and artificial flower wreaths that women used to decorate their hair and clothes.

15 The wreaths in particular could cause rashes for women who wore them. But like mercury hats, arsenic fashions were most dangerous for the people who manufactured them, says Matthews David.

16 For example, in 1861, a 19-year-old artificial flower maker named Matilda Scheurer—whose job involved dusting flowers with green, arsenic-laced powder—died a violent and colorful death. She convulsed, vomited, and foamed at the mouth. Her bile was green, and so were her fingernails and the whites of her eye. An autopsy found arsenic in her stomach, liver, and lungs.

17 Articles about Scheurer’s death and the plight of artificial flower makers raised public awareness about arsenic in fashion. The British Medical Journal wrote that the arsenic-wearing woman “carries in her skirts poison enough to slay the whole of the admirers she may meet with in half a dozen ball-rooms.” In the mid-to-late 1800s, sensational claims like these began to turn public opinion against this deadly shade of green.

Safety in Fashion

18 Public concern over arsenic helped phase it out of fashion—Scandinavia, France, and Germany banned the pigment (Britain did not).

19 The move away from arsenic was hastened by the invention of synthetic dyes, which made it “easy to let arsenic go,” according to Elizabeth Semmelhack, senior curator at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, Canada….

20 This raises interesting questions about fashion today. While arsenic dresses might seem like bizarre relics of a more brutal age, killer fashion is still very much in vogue. In 2009, Turkey banned sandblasting—the practice of spraying denim with sand to give it a fashionable distressed look—because workers were developing silicosis from breathing in sand.

21 “It’s not a curable disease,” Matthews David says of silicosis. “If you have sand in your lungs it will kill you.”

22 Yet when a dangerous production method is banned in one country—and when the demand for the clothing that method produces remains high—then production typically moves somewhere else (or continues despite the ban). Last year, Al Jazeera found that some Chinese factories were sandblasting clothes.

23 In the 1800s, men who wore mercury hats or women who wore arsenic-laced clothing and accessories might have seen the people who produced these items on the streets of London, or read about them in the local paper. But in a globalized economy, many of us don’t see the deadly effects that our fashion choices have on others.

Source: “Killer Clothing Was All the Rage in the 19th Century,” Becky Little, National Geographic News Online, October 17, 2016. Reproduced by permission of National Geographic Creative.

1. Based on the passage, how would the author likely account for a man who locks his door and checks his windows at night, yet uses the same password for several different online accounts?

A. He believes there is no security risk involved in online accounts.

B. He feels responsible for safeguarding his tangible assets (such as his house and its contents), but not for intangible cyber assets (such as his online accounts).

C. A burglar would be a specific person whom the police might catch; an online attacker could be in any country and would likely remain unknown.

D. He’s not aware that reusing the same password makes all of his accounts vulnerable to attack.

Here’s a two-part main idea question. First you need to determine which main idea (for the entire passage? for a section of it?) is relevant to the question. Then you need to do something with that main idea. In this case, the question asks you to speculate about how a main idea would apply to a new situation.

Here’s How to Crack It

A good way to approach this type of question is to start by eliminating answer choices that have nothing to do with any of the main ideas in the passage. If you used active reading techniques, you should have identified the main idea of each section of the passage as you were going through it, so you should already have a list (either in your head or else jotted down in a few key words).

The passage discusses health risks, not security risks, and in several cases implies that those health risks were well known, so (A) can be eliminated. Choice (B) can also be eliminated, since that answer choice discusses protecting an asset, while the passage doesn’t have any main ideas about the security of assets. The passage doesn’t contain a main idea about lack of awareness making someone vulnerable to an attack, so (D) can also be eliminated.

What about (C)? That’s close to the main idea in the last paragraph: concern about a local, identifiable person but lack of concern about someone far away and who can’t be seen or identified. So the correct answer is (C).

2. One reason the author introduces the present-day fashion industry is to

A. show that nothing has changed with respect to unsafe manufacturing techniques.

B. illustrate the effect of globalization.

C. demonstrate how public concern about the welfare of fashion workers has increased.

D. explain how fashion manufacturing has changed since the 1800s.

This development question concerns the overall way in which the author connects, develops, and organizes her ideas.

Here’s How to Crack It

You need to look at a development question in the context of the overall chain of ideas in the passage. In this case, why does the author move from discussing fashion manufacturing in the 1800s to the modern day? She has described how mercury disappeared when hats went out of fashion, and how synthetic dyes accelerated the end of arsenic. But so what? Does that mean today’s fashion industry is safe? Moving on to the present allows her to answer those questions.

She makes an abrupt transition which still skillfully manages to connect the two eras (“This raises interesting questions about fashion today,” paragraph 20). Then she goes on to say that at least one unsafe technique (sandblasting) is used today. So her answer is no, the fashion industry still isn’t free of danger.

At first glance, it seems that none of these choices hit that mark accurately. In a case like that, the best approach is Process of Elimination (POE)—first get rid of the most clearly wrong answers and see which one (or possibly two) remains.

Choice (A) uses extreme language—saying “nothing has changed”—which is usually a suspect answer in a GED® question. Some manufacturing techniques have changed; arsenic and mercury are no longer used, for example. Another clearly incorrect answer is (D). The author gives one example (sandblasting) of present-day “killer fashion” which, she says, is “still very much in vogue” (paragraph 20). So, today’s fashion industry still contains dangers, even if today’s specific hazards are different from those of the 1800s.

Choice (C) is also incorrect. Public concern has not increased since Matilda’s well-publicized death raised an outcry that helped end the use of arsenic. In fact, public concern has declined. Why? “In a globalized economy” (paragraph 23), banned sandblasting simply moved from Turkey to China, and the deadly effects on workers are hidden far away from the consumers who wear the sandblasted products. So the correct answer is (B). The industry still presents dangers to fashion workers today, as it did in the 1800s, and a global economy has made their situation more hopeless.

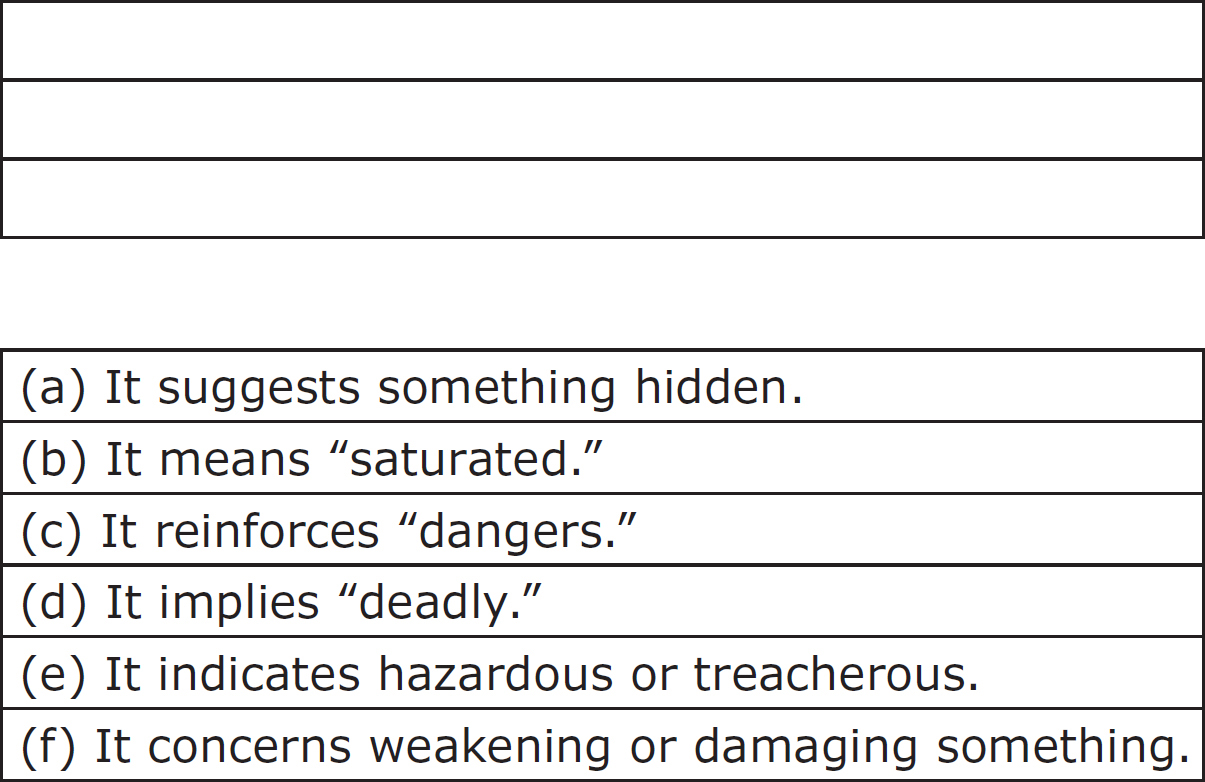

3. In paragraph 3, the author claims that “fashion at this time was riddled with dangers.” What connotations (implications or suggestions) does the word “riddled” add to her description of fashion? Drag the most accurate answers into the empty boxes below. (For this example, letters have been added to each answer choice to clarify the explanation that follows.)

In this language use question, you’ll need to consider the context of the passage as a whole to determine why the author chose to use a particular word.

Here’s How to Crack It

Think about the main idea the author conveys about Victorian fashion. Some pieces (hats, skirts, combs, even socks) posed health hazards for the wearers and especially for the producers. However, not everyone died as a result. And not every piece of clothing is described as being dangerous. So the extreme choices—(b) and (d)—can be ruled out. Fashion wasn’t thoroughly filled, or saturated, with danger (b) and wasn’t always deadly (d). The dangers weren’t hidden, either—Matilda’s death from arsenic was widely publicized, and medical examiners documented the effects of mercury on the hat-makers. That eliminates (a).

So the remaining three answers must be correct (to fill the three boxes) and indeed, they are. The use of “riddled” reinforces the idea of danger (c)—think “riddled with bullets” or “riddled with corruption.” It indicates that something is hazardous or treacherous (e), although not always deadly, as the more extreme (d) says. And it portrays fashion as weakened or damaged by the dangers, as a solid material is weakened or damaged by numerous punctures, as in (f).

4. What primary function do the anecdotes about Fanny Longfellow and Matilda Scheurer serve in the passage?

A. They introduce humor to the author’s tone.

B. They add credibility to the passage.

C. They help the author connect with her readers.

D. They demonstrate how thoroughly the author has researched her topic.

Here’s a structure question: Why did the author include these anecdotes? What do they add to achieving her purpose?

Here’s How to Crack It

A good way to approach this type of question is to ask yourself what the passage would be like without the structural elements identified in the question (the anecdotes, in this case). If you’ve practiced active reading techniques (asking yourself about the author’s audience, main point, purpose, etc.) as you worked through the passage, you should have a good idea of what the author is trying to achieve. Could she do it as effectively without the anecdotes? Why not?

Right at the beginning of the passage we learn that poor Fanny died after her dress caught fire. This introductory anecdote draws readers in and stimulates their interest in a way that a straightforward opening statement (such as “Clothing was dangerous in Victorian times”) never could.

And just before we hear about Matilda’s “violent and colorful death” from arsenic, the author gave a detailed account of the adverse health effects suffered by hat-makers because of mercury. In Matilda’s case, though, we know the victim’s name, her age, and the era in which she worked. The vivid focus on one girl’s tragic death gives readers a high-impact, memorable example of unsafe work in a way that the broader, generic description of hat-makers doesn’t.

So the anecdotes arouse readers’ interest and make them understand—through the story of a specific person’s fatal experience—how serious the issue of dangerous clothing was to both consumers and workers. Which of the answer choices best reflects that function?

There is an element of probability to each choice, although (A) would point to very dark humor, so it can be eliminated first. Next to go is (B). The question stem asks for the primary function of the anecdotes, and the author’s references to experts and books convey credibility more than the two anecdotes do. Choice (D) can be eliminated for a similar reason: there are many other descriptions in the passage that point to thorough research, so that’s not the primary function of the anecdotes.

That leaves (C). The author connects with her readers through anecdotes that capture their attention and convince them of the importance of the topic. Both are necessary for the author to achieve her purpose of informing a general audience in an interesting, entertaining way.

This approach of finding the correct answer by first eliminating the incorrect choices is called Process of Elimination. When there is some element of truth to each choice, as there is here, it’s usually the fastest, most accurate way of finding the correct answer.

5. What is the relationship between the author’s point of view and her purpose?

A. The point of view is aligned with the author’s purpose.

B. A different point of view would advance her purpose more effectively.

C. Her point of view changes at different points in the passage.

D. The purpose and point of view work against each other.

This purpose/point of view question demands a “big picture” analysis of the passage as a whole.

Here’s How to Crack It

First you need a firm grasp of what the author’s purpose and point of view are. The title tells you that this passage is drawn from National Geographic, which attracts a general audience with an interest in learning more about our world. Even if you’re not familiar with National Geographic, the intriguing topic and the author’s explanation of terms (such as “neuromotor problems”) suggest a general audience. The author’s purpose, then, would be to inform this audience, but in an interesting, entertaining way that would capture and hold the audience’s attention. She likely hopes that, after reading the article, some readers might stop to think about whether any fashion worker was put at risk by making the article of clothing they’re about to put on.

What about her point of view? As (C) points out, the author’s point of view does change. It is at times neutral, at times authoritative (when she cites scholarly books about Victorian fashion, for instance), at times mildly critical, at times humorous. Those are all consistent with her purpose of informing while entertaining and arousing interest. That makes (A) the correct answer—the purpose and point of view are aligned.

Choice (C) is incorrect because it deals with only half of the question. It ignores purpose and how that relates to these changing points of view. Choices (B) and (D) say essentially the same thing: the author’s point of view and purpose are not working together, which is not correct.

6. As the passage describes the end of dangerous materials and manufacturing techniques, the underlying assumption is that

A. consumers preferred fashion over their own safety.

B. the practice was so entrenched that external pressure was required.

C. consumers valued themselves more than they valued the workers who produced fashion garments.

D. fashion workers had no power to bring about change.

This evaluation question requires you to identify the assumptions underlying a topic.

Here’s How to Crack It

You need to zero in on the specific topic raised in the question—the end of a dangerous practice—and not be distracted by the extensive range of fashion dangers the author covers, from fire-prone dresses to sandblasted jeans. The passage describes only two cases of a dangerous practice actually ending: the mercury hats and the arsenic flowers. To what does the author attribute those two endings? “Men’s hats went out of fashion” (paragraph 12) in the former case, and a combination of “public concern” (paragraph 18) and “the invention of synthetic dyes” (paragraph 19) in the latter.

Now you just need to see which answer choice applies to both of those two cases. It’s not (A); the author says that mercury didn’t pose any danger to the consumers who wore the hats. It’s not (D), either; the author implies that the hatters chose not to stop making hats with mercury. Choice (C) is tempting. However, the passage doesn’t say whether consumers were even aware of the dangerous effects of mercury on the hat-makers, and Matilda’s death from arsenic did raise public concern. That leaves (B) as the correct answer. Hats went out of fashion, public concern about arsenic was aroused, and synthetic dies were invented to replace it. The need for external pressure to stop the use of mercury and arsenic suggests that the practices were so entrenched they would have continued otherwise.

Now, assume that the passage is paired with the following brief excerpt.

Rocky Flats: From Hazard to Haven

1 On the site of what was once a highly contaminated nuclear weapons production facility, the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge is committed to protecting endangered species. Visitors can now hike, take guided nature tours, cycle, or horseback-ride along a year-round trail system. The grand-scale cleanup, initially estimated at $37 billion over 60–70 years, was completed within 10 years for just $7 billion.

2 But just how safe is this former weapons plant site? The debate revolves around the concerns of thousands of nearby homeowners who claim that residual plutonium and other toxins put their health at risk.

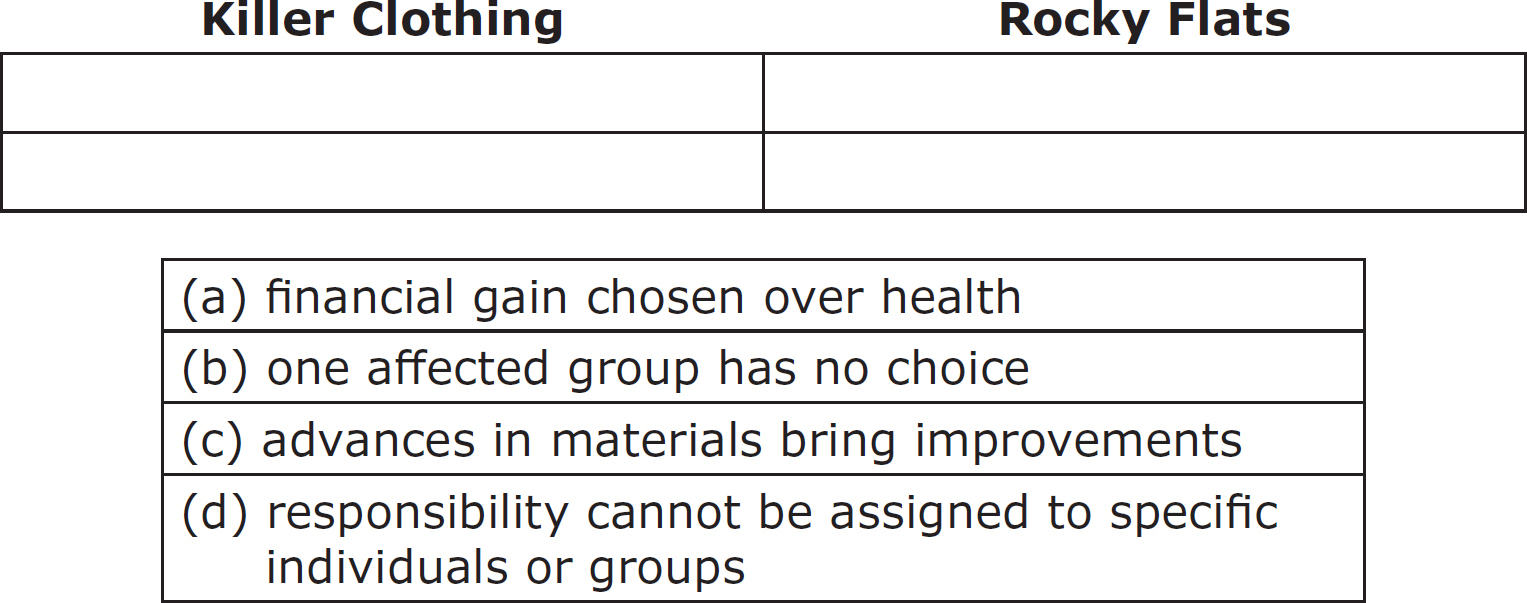

7. Drag and drop the concept or theme evident in each passage under the correct passage on the chart. (For this example, letters have been added to each answer choice to clarify the explanation that follows.)

This comparison question requires you to grasp and analyze the major themes of two works that deal with similar topics.

Here’s How to Crack It

Four empty boxes, four answer choices. There are no “extra” alternatives to eliminate as a starting point. In a case like this, the best approach is simply to look at each concept or theme in turn and decide which of the two readings best exhibits that trait. If you’re not sure about one choice, skip it and see if there’s an empty box left for it at the end.

The concept of choosing financial gain over health is explicitly stated only in the Killer Clothing excerpt. Hat-makers knew the dangers of mercury, but “viewed them as the hazards that one had to accept with the job” (paragraph 11), so (a) falls under Killer Clothing. The Rocky Flats excerpt does not say that developers knew about the potential dangers and deliberately chose to put hikers and homeowners at risk.

Only one group—“endangered species” (paragraph 1) living in the Rocky Flats refuge—has no choice about being exposed to risk. All of the other affected groups in the two excerpts could theoretically educate themselves about the risks and choose not to buy dresses with hoop skirts, for example, or make sandblasted jeans. They could choose not to live or even hike next to a former nuclear weapons plant. So (b) goes in the Rocky Flats column.

Choice (c) goes under Killer Clothing, since the development of synthetic dyes helped eliminate arsenic as a production material. The Rocky Flats piece does not mention any advances in materials that would have made the surprisingly low-cost, speedy remediation effort more effective.

The Rocky Flats excerpt does not provide enough information to assign responsibility, so (d) goes in that column. Did the government or the weapons production company undertake the cleanup? Who decided to build a residential development and trail system next to such a potentially dangerous site? On the other hand, responsibility can be assigned in the Killer Clothing piece—consumers created a market for dangerous clothes, hatters wanted to earn money despite the risks, and employers hid the dangers of arsenic from the flower-makers.

Over to you now. Ask yourself the active reading questions as you go through this passage, and make sure your critical thinking skills are in gear. Then try the questions, using your knowledge of the seven question tasks. (The order of those tasks is mixed up in this drill, as it will be in the test.) You can check your answers and reasoning in Part VIII: Answer Key to Drills.

Companies use statements of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to explain the values and principles that govern the way they do business, and to make a public commitment to follow them. These documents typically have high-level support from management and the board of directors, and are made available to all stakeholders, from employees to investors, customers to government regulators.

Pine Trail Timber—Statement of Corporate Social Responsibility

1 In carrying out our mission to supply the residential construction industry with the highest quality products from sustainably managed sources, Pine Trail Timber adheres to the following commitments to its stakeholders, to the communities in which it does business, and to the environment.

Responsibility to Stakeholders

2 Our stakeholders place their trust in us, and we work every day to merit that trust by aligning our interests with theirs.

3 All employees deserve a safe, supportive work setting, and the opportunity to achieve their full potential. We stress safety training, prohibit any type of discrimination or harassment, and support employees’ efforts to enhance their job-related skills. In return, we expect our employees and officers to devote themselves to fulfilling our commitments to other stakeholders.

4 Investors have a right to expect transparency, sound corporate governance, and a fair return on their investments. We pride ourselves on full disclosure, adherence to the most rigid standards of ethical oversight, and a track record of profitable operations, as our rising stock chart and uninterrupted five-year series of dividend increases show.

5 Our valued customers are entitled to exceptional value and service. Our product innovation and wise management of resources ensure that they receive both.

6 Our suppliers rely on us for fair dealing in specifying our requirements and in meeting our obligations. We consider our suppliers to be our partners—when we succeed, they succeed.

7 We meet the expectations of government and industry regulators by complying with all applicable laws of the countries in which we carry out our business operations, and cooperating in all authorized investigations.

8 We fulfill our duty to the media and the public through providing timely information about any events that might have an impact beyond our operations, and making senior spokespeople available on request.

Support for Local Communities

9 We aim to enhance our host communities. Our presence provides training and jobs, and contributes to the local economy.

10 In the field and in our processing facilities, we recognize the impact our activities may have on local groups. We strive for open communication in order to build relationships, and create opportunities for consultation to foster understanding of our plans.

11 In urban centers where we have administrative operations, we match charitable donations made by our employees and run programs that give employees a block of time off work to volunteer with local organizations. Pine Trail Timber routinely forms one of the largest volunteer groups in the annual Arbor Day activities in several countries, planting trees and teaching other participants how to care for them.

Respect for the Environment

12 We recognize that our current and future success depends on the wise use of renewable resources. We value our reputation as a conscientious steward of the lands that furnish our products.

13 All of our production and processing operations worldwide are certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) as meeting its rigorous standards for responsible resource management. The FSC certification assures our stakeholders and host communities of independent verification of our operations.

14 Through constant process innovation, we aim to make the least possible use of non-renewable resources in our production.

15 We strive to leave the smallest possible footprint and, where necessary, carry out prompt and thorough remediation. After we finish our operations in an area but before we leave, we ensure that the land is returned to a state where it can produce abundant crops, offer a welcoming home for wildlife, and provide outdoor enjoyment for local residents.

We’re Listening

16 If you have any questions or comments about our Corporate Social Responsibility commitments, we invite you to contact Mr. Joseph d’Argill, our Chairman and Chief Executive Officer.

1. The CSR statement specifies that employees are expected to “devote themselves to fulfilling our commitments to other stakeholders” (paragraph 3) because

A. the authors of the CSR statement are worried that they can’t take responsibility themselves for the promises they’re making.

B. the authors know that stakeholders will usually be dealing with lower-level employees instead of with the senior executives and board members who created the CSR statement.

C. the authors want to exert additional influence on employees through this public statement that stakeholders can expect everyone who works for Pine Trail Timber to fulfill these commitments.

D. employees work in many different locations and countries, far from the home office where the senior executives and directors behind the statement work.

2. When the company refers to “obligations” (paragraph 6), it means

A. its responsibilities as a good corporate citizen.

B. burdens it must bear.

C. its duties.

D. money it owes.

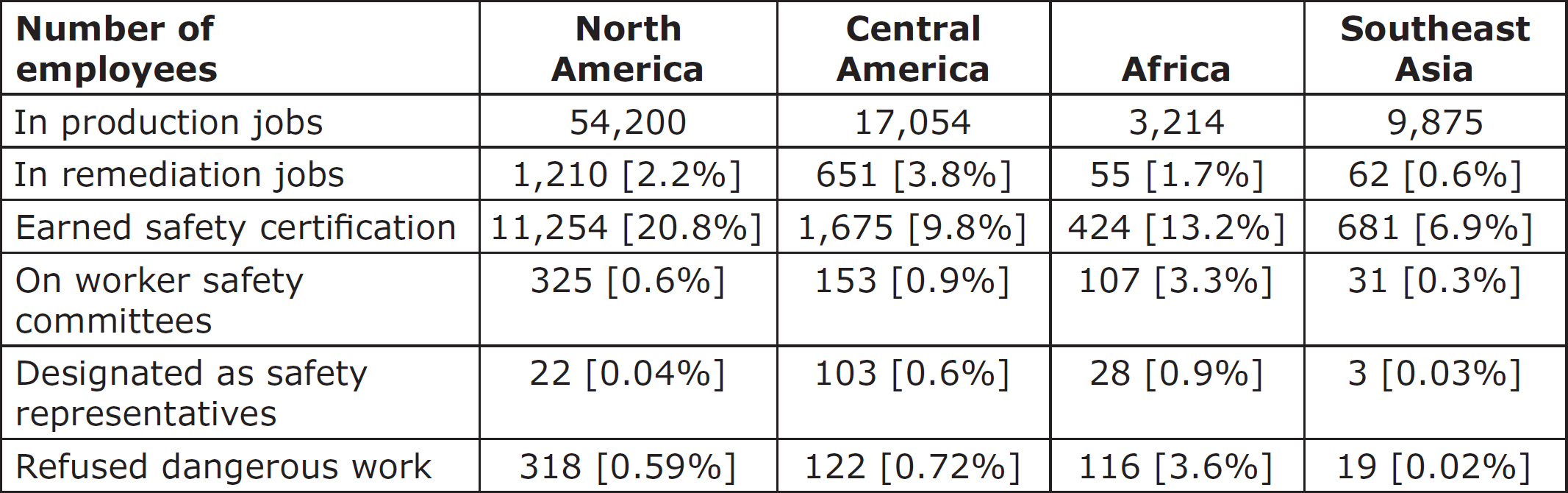

Question 3 refers to the following table.

3. Compare the figures in the table above to the overall company image portrayed in the CSR statement. From the answer choices below, identify the most significant similarity or difference in topics covered by both of the two sources. (Assume the percentages shown in the table are correct; you do not need to calculate them.)

A. The table suggests the safety and remediation commitments made in the CSR statement apply unevenly to different geographic locations.

B. The table reinforces the extensive worldwide operations suggested in the text statement.

C. The table reveals that workers have more control over their safety than the text statement says.

D. The table confirms the CSR statement’s commitment to restoring the land after the company’s work there is complete.

4. The authors wrote and published this CSR statement because

A. government regulations require them to do it.

B. they want to present a public image of Pine Trail Timber as a responsible, ethical, trustworthy company.

C. all of their competitors in the forestry industry have one.

D. they want to explain the company’s mission.

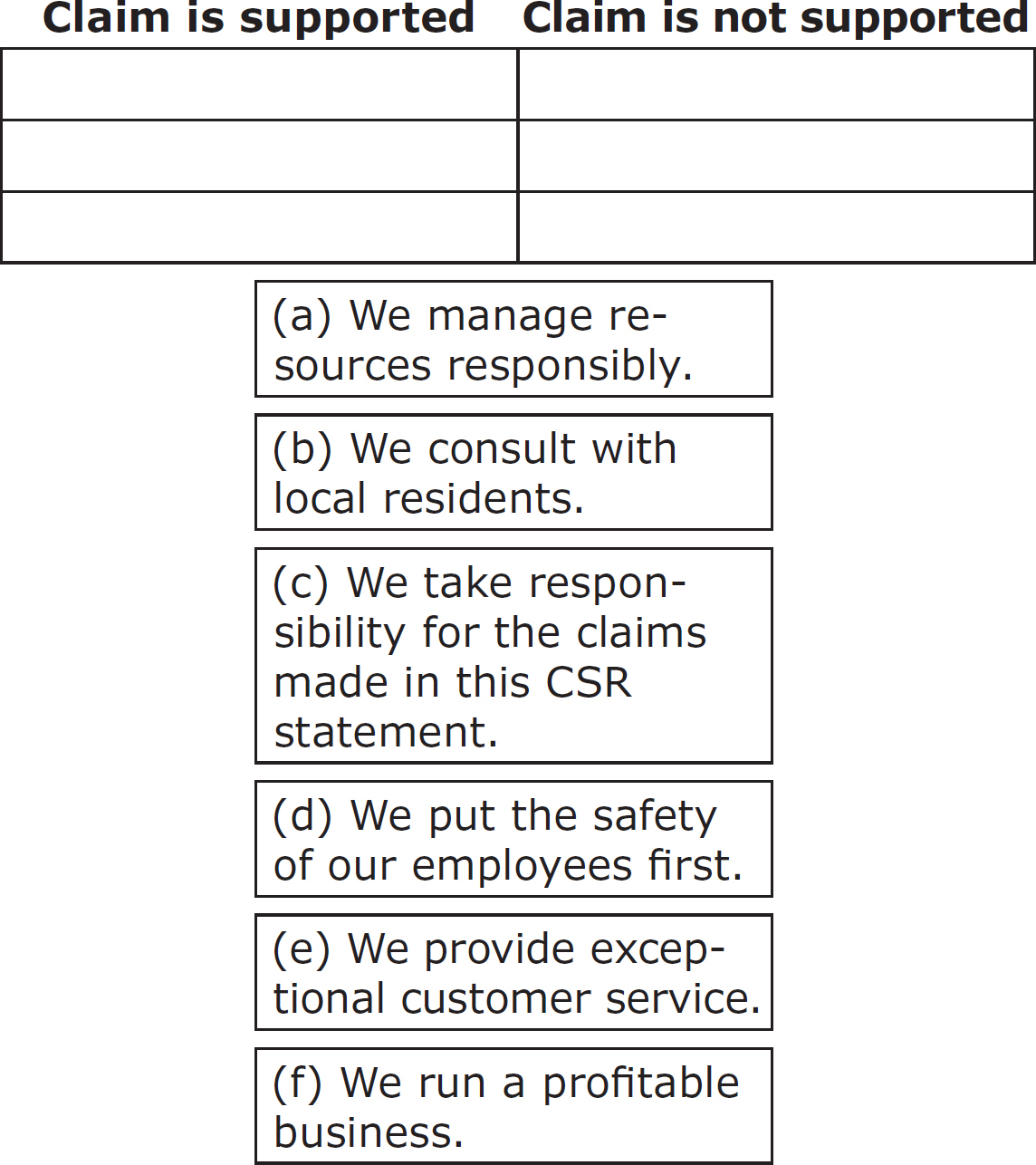

5. Decide whether the claims below are supported in Pine Trail Timber’s CSR statement or whether the company makes the claim without providing support for it. Drag each claim to the appropriate column in the chart.

6. Considering the overall theme of the CSR statement, what conclusion can you draw from the last two paragraphs in the “Responsibility to Stakeholders” section (paragraphs 7–8)?

A. The company sometimes fails in its goals of being a trustworthy steward and improving the areas in which it has operations.

B. Responsibilities to regulators and to the public are considered less important than responsibilities to employees and other stakeholders.

C. The company fosters close relationships with governments and the media.

D. There is a strong sense of responsibility to stakeholders who are not directly involved with the company’s business operations.

7. What is the most significant contribution made by the mention of Arbor Day (paragraph 11) to the company image portrayed in the CSR statement?

A. It reinforces the global nature of the company’s operations, since Arbor Day is celebrated in many different countries.

B. It supports the company’s claim of giving employees time off work to volunteer for charitable activities.

C. It would help attract potential employees who want to preserve the environment.

D. It demonstrates the company’s wise use of resources, since participation in Arbor Day would replace some of the trees the company takes in its harvesting operations.