If any part of the Reasoning Through Language Arts (RLA) Test could make prospective test takers gasp and rethink their plan, it would be the Extended Response section.

You can relax, though. No, really—relax. With the strategies you’ll discover in this book, you’ll have a process and a plan for tackling the Extended Response, so you won’t have to waste time figuring out your approach on test day. You’ll know exactly what to write about and where to start, and you’ll gain some good tips for improving your writing, too.

First we’re going to look at what you’re doing for the Extended Response section. Then, in the next chapter, we’ll look at some strategies for how to do it.

You’ll tackle the 45-minute Extended Response question right after the 10-minute break that follows the first reading and language section. The prompt will include two passages arguing opposite sides of a real-world “hot button” issue such as oil pipelines or the minimum wage. The passages could come in different formats (for example, an employee memo and a magazine article). The authors might also be quite different—a professional teacher and a concerned parent, for instance.

Your task is to explain which passage provides better support for the position it argues. The passages have been chosen so the support they provide is roughly equal. There is no “right” or “wrong” passage. In other words, you could argue effectively that either one of the passages provides better support. As you read through them, you might find that one type of support is more familiar to you, or that you feel more comfortable with one format. Choose the passage for which you feel you could build a stronger argument.

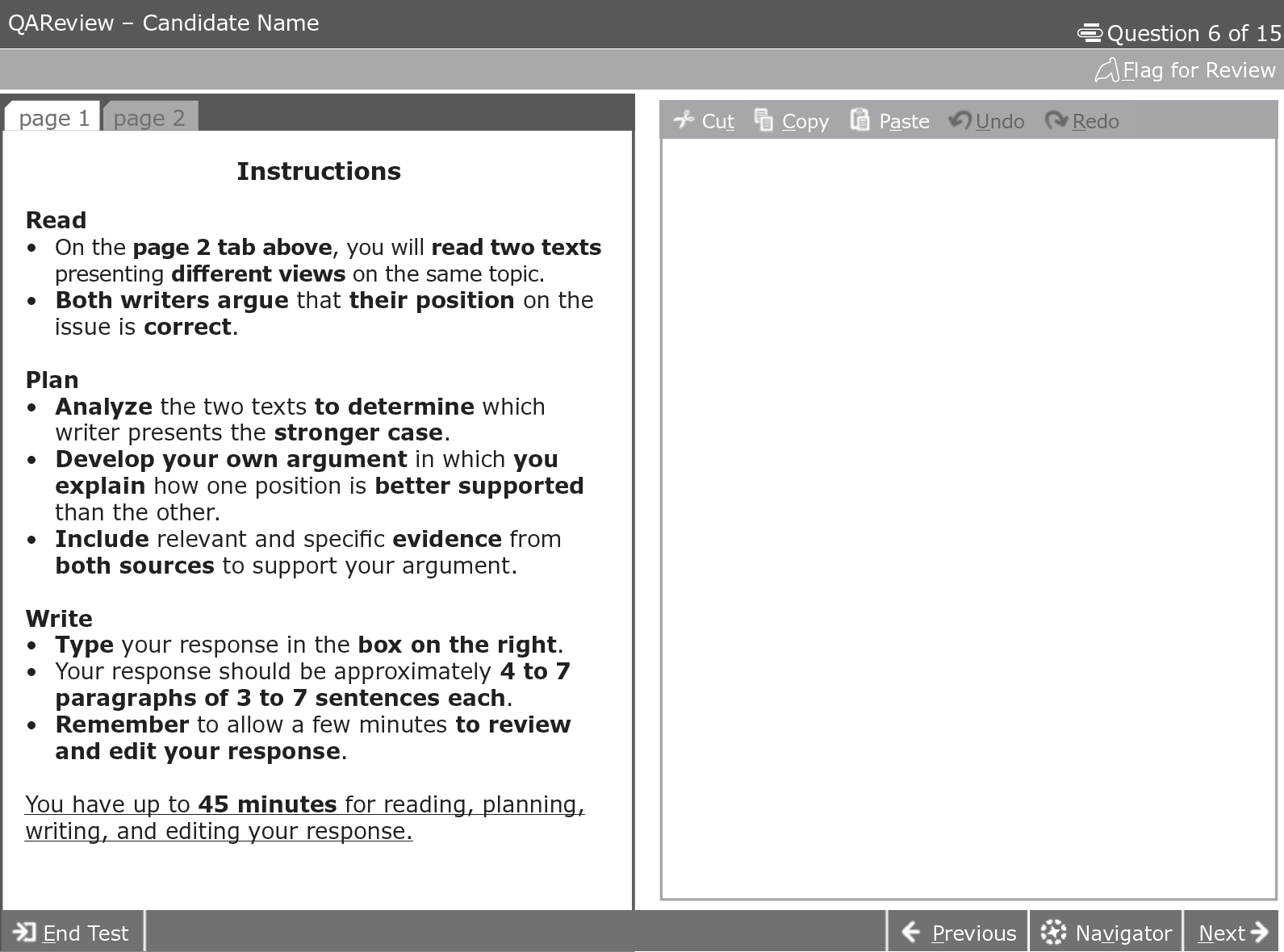

The Extended Response screen was recently reformatted to provided clearer instructions and a more user-friendly interface for typing your answer. It has three main components.

The prompt (also known as the instructions) describes your task and appears on the left side of the screen on the “page 1” tab. It has four parts, which we’ll describe next.

The passages themselves appear on the “page 2” tab. Make sure to read both passages. Together they will be about 650 words.

The paragraphs are numbered consecutively so when you’re writing, you’ll be able to find points that you’ve already noted more quickly. If the first passage ends with paragraph 5, then the second passage will begin with paragraph 6.

The third part of the Extended Response screen is a text box occupying the right half of the screen. As you type your response, a scroll bar will appear on the right-hand side to let you review your essay.

There are no spelling or grammar checkers. You can cut, copy, and paste within the text box, but you can’t copy text from the passage and paste it into your essay.

While the passages on page 2 will vary, the instructions on page 1 will always have the same four components.

Four Parts of the Extended Response Prompt

The prompt first asks you to read the two texts on the page 2 tab. These texts present different views on the same topic, and both argue that their position is correct.

Then it asks you to plan your essay by first deciding which writer presents the stronger case, and then developing an argument explaining WHY. Determine what specific evidence you can use to support your argument.

Next, write your response. Note that in order for your response to count, it should be approximately 4 to 7 paragraphs in length, and each of these paragraphs should contain 3 to 7 sentences.

Finally, it ends with a note about the time: “You have up to 45 minutes for reading, planning, writing, and editing your response.”

Here are some important tips to keep in mind about the task that’s described in the prompt.

Take a step back from the topic. Two authors are making opposing cases about an issue. Your mission is to look at how they make their cases, not at the cases themselves. Focus on the support provided by the two authors, not on the topic they’re discussing. If, for example, you think burning coal is a major cause of climate change and air pollution but you feel that the passage promoting clean coal has better support for its position, then your essay will explain how the clean coal passage is better supported. It won’t discuss the issue of burning coal. Your grade will be lowered if your essay strays far from support to the topic itself. (We’ll explain later on how the essay is graded.)

Stick to the passages. That’s where you’ll find the support. If you bring in your own opinions or knowledge about an issue, you run the risk of wandering into an essay about the topic instead of an essay about how the two authors make their cases.

Back up your points with evidence from the passages. For instance, perhaps you feel that one passage provides stronger support because it mentions specific studies and experts instead of simply making vague claims. Your essay should refer to those specific details.

There are no right or wrong answers. If you can make a credible case that one side of the argument provides better support, and back that up with evidence from the passages, then your position will not be considered wrong.

Support can take several forms, which we’ll outline below. You might also find it helpful to review the section on evaluation questions in the reading part of the test (this page in Chapter 5), because that’s exactly what you’re doing here—evaluating the evidence, reasoning, and assumptions of two authors to argue that one has provided better support for his or her position.

The most obvious type of support would be evidence—examples or other details that the author provides, or authorities the author cites. Elements such as those can add a lot of weight to an argument. Consider this example:

The polar bear population is threatened.

vs.

A 2006 study revealed that the skull size and body weight of adult male polar bears in the Southern Beaufort Sea population had decreased during the past 20 years. Fewer cubs were surviving, too. Scientists saw both measures as symptoms of stress, and a repeat of the warning signs noticed earlier in the polar bears of Western Hudson Bay. There, the population subsequently fell from about 1,200 in 1987 to about 950 bears 17 years later.

Clearly the second claim provides stronger support for this specific point. It outlines specific research studies, years, symptoms, and numbers; and it builds its case on the findings of scientists, who are the authorities in the field.

Support through evidence can be a bit less clear cut, too. For instance, suppose one side of the argument makes only one major claim, but backs up that claim thoroughly with evidence from professional research studies and the opinions of acknowledged experts in the field. The other side gives four reasons for its position instead of one, but doesn’t offer as much support for any of them. Which one is stronger? There are no right or wrong answers, as long as you can build a credible argument and support it from the passages. In this case, you would choose the side for which you can do a better job of explaining why the support for that position is stronger. Another test taker might choose the opposite side and that’s fine, as long as he or she can explain what makes that side’s support better.

When you’re looking at evidence-based support, watch for adequacy and relevance, too. Does the author provide enough credible evidence in comparison to the other passage, and is that evidence relevant to the claim the author is making?

This support issue is more subtle than evidence-based support. Is the author’s chain of reasoning sound and logical? Or do you detect a logical fallacy? (See this page in Chapter 5.) Do the author’s claims seem well supported by evidence, but when you follow the path from claim to conclusion, does it go seriously off course?

Suppose, for example, an author claims that purple loosestrife, an invasive plant species, is harming natural wetlands in the area by discouraging wildlife and beating out native plants in the competition for nourishment and space. Studies done during the past three years show the retreat of native species and the alarming spread of purple loosestrife, backing up this claim. So far, so good. But then the author says that this means that the town authorities should begin a program of spraying toxic chemicals on wetlands in order to eliminate the invasive plant. The author is making a big leap, going from saying that there’s a problem (and presenting evidence) to insisting on a drastic solution (without evidence for the solution being a good one). What happens to the remaining native plants if toxic chemicals were sprayed? And what about the wildlife in the area? The claim looks good, the evidence looks good, but the reasoning leading from the claim to the extreme solution is flawed. Because of its faulty reasoning, the author’s position is not well supported.

Another subtle support issue involves the author’s assumptions. Are they valid, considering the likely audience? All the evidence and logical reasoning in the world doesn’t make a well-supported argument if the assumptions on which it’s based don’t make sense. Consider, for instance, an author who wants to add life to a new suburb filled with young families. The writer argues that $20 should be added to each property tax bill to fund facilities for a Wednesday morning fruit and vegetable market in the local park. The piece includes compelling evidence of the health benefits of eating fresh fruits and vegetables, and the wisdom of buying produce grown “close to home.” What’s wrong with this argument? The author is assuming that there will be enough customers on a Wednesday morning (the traditional market day) to make the project a good business proposition for vendors. What about the suburban adults who have day jobs and their kids who are in school? The invalid assumption drains support from the author’s position.

The Extended Response task pulls together the critical thinking, active reading, analytical, and language skills you’ll also use in the reading and language sections of the RLA Test. As in other sections, the aim is to allow test takers to demonstrate the skills required for college or a career.

In the Extended Response section, you’ll be graded on how well you can:

understand and analyze the two source passages

evaluate the argumentation in those passages

create a written argument in your own words, supported by evidence drawn from the passages

One bit of good news: Because you have only 45 minutes to plan, write, and edit the essay, it’s considered an “on-demand draft” and is not expected to be completely free of errors.

Your essay is scored on three separate rubrics. Each one covers a trait that should be evident in your essay.

This trait looks at two aspects of your essay: how well you build an argument for your position about which passage is better supported, and how well you incorporate evidence drawn from the passages. We’ll give you some practice Extended Response questions in the next chapter. The following questions will help you evaluate your own practice essays for this trait:

Did you establish a purpose that’s connected to the task in the prompt? In other words, is it clear that your purpose is to explain why one passage is better supported than the other (instead of discussing the topic of the two passages)?

Did you make clear claims?

Did you explain why the evidence you’re taking from the passages is important (instead of simply plunking it into your essay without any commentary)?

Have you demonstrated that you can distinguish between supported and unsupported claims in the passages?

Have you shown that you can evaluate the credibility of the support the authors use?

Have you spotted any faulty reasoning in an author’s argument?

Are you making reasonable inferences about the assumptions underlying the authors’ arguments?

Now that you’ve shown you can create a solid argument for your position, we’re moving on to how well you develop and organize that argument. Here are some questions to ask yourself about your practice essays:

Did you explain how your ideas are relevant to the task, or did you just fire off ideas without elaborating on them?

Is there a logical progression to your ideas, or do they jump around all over the place? (You might find it helpful to review the transition and signal words on this page in Chapter 5.)

Is there a clear connection between your main points and the details that elaborate on them? (In the next chapter, you’ll learn more about connecting main points and accompanying details.)

Do the style and tone of your essay demonstrate an awareness of your audience and purpose? (Do you use complete sentences most of the time, instead of bullet lists? Is the language appropriate, or is it filled with slang and inappropriate short forms?)

Did your organizational structure contribute to conveying your message and purpose? (We’ll talk about organizing your argument in the next chapter.)

There’s just one question to ask yourself for this trait: Did you follow all eight of the language skills described in Chapter 8? The editing questions in the Language assessment were the first part of testing you on the elements of language use that are considered most important for a career or college. The writing task in the Extended Response section is the second part.

Yes. The essay is graded by computer, so you won’t have to wait weeks for your results. In fact, the scoring is done almost immediately. Scoring by computer (instead of tying up a bunch of human graders) also allows for giving you specific feedback on your essay performance as part of the score report.

How can a computer (actually, it’s called an automated scoring engine) do an accurate job of assessing your unique, original essay? The test writers spent months teaching it, feeding it the scores awarded by human graders to an extensive range of sample essays so it would learn the characteristics of, say, a high score on the trait of “development of ideas and organizational structure.” If the scoring engine doesn’t recognize something about an essay (one that’s unusually short, for instance, or that uses uncharacteristically sophisticated vocabulary), it kicks the essay out to a human grader. However, the test writers are confident that the engine will score at least 95 percent of the essays accurately.

Now that you understand the Extended Response task and the traits you need to demonstrate in your essay—that’s the “what”—we’ll move on in the next chapter to the process for building and organizing your argument—the “how.” We’ll walk you through that process, using some examples and then give you one to try on your own. Along the way, you’ll pick up some tips for improving your writing in any type of task, too.