6

‘A murderous curtain of lead’

Gona

November to December 1942

Gona was no place to wait for death. To die slowly in the stifling heat beneath the tropical sun was an all-too-real vision of hell. But that was Lieutenant Bruce Taylor’s fate as he lay in agony in the tall, dense kunai grass, hardly able to move, the wound in his throat making it impossible even to drink. For seven days Taylor lay there, within 15 metres of the Japanese defences, trying to stay alive by lying in pools of water. On the seventh day he was wounded again, this time by a bomb splinter from his own side gouging out a piece of his shoulder. In agony and with all hope gone, Taylor gave himself up to death. Dragging himself towards the enemy position, he tried to shout, ‘Shoot, you little bastards, shoot me, kill me!’ But no words would come from his throat.1

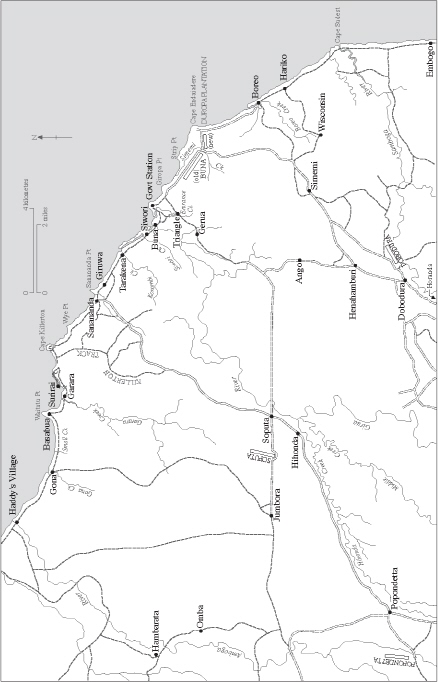

When the Australian infantry reached the coast of northern Papua in late November, American troops were already in action at Buna and Sanananda. The immediate Australian objective was just to their allies’ west: the Japanese beachhead at Gona. Brigadier Eather’s 25th Brigade closed on the Anglican mission, and on 18 November, about 1.5 kilometres to its south, they began clashing with the enemy. By the next day, they were encountering ferocious resistance. The Japanese had established a strong position at Gona Mission. Dug in to trenches, they were protected by the sea to their north and Gona Creek to the west, and had razed the kunai grass to clear fields of fire around their machinegun posts. Without sufficient supplies to make a concerted attack, Eather ordered his forward companies to dig in.

On 22 November, the 2/31st Battalion moved around the defenders’ eastern flank and found a way through to the shoreline east of Gona. Once the ocean was in view, the four companies turned west and moved towards the mission until they reached a clear patch in the kunai. At dusk, the men rose and charged, only to be met by a storm of enemy fire. It was a brutal introduction to the interlocking Japanese defensive line on the mission’s eastern side: the battalion took sixty-five casualties. The stretcher bearers worked like Trojans that night to get out the wounded, often up to their waists in water.2 They didn’t find the muted Bruce Taylor until 30 November. He would never recover from his eight days in hell: evacuated to Australia, this tenacious survivor would lose his fight for life on Christmas Day.

The 2/25th Battalion was also badly beaten, with seventeen men killed and another fifty-two wounded. Heat exhaustion and malaria also felled ever increasing numbers of troops. The 25th Brigade, already severely depleted by the Kokoda campaign, was near the end of its tether. In the first four days in the line at Gona, the brigade took 204 battle casualties. On the late afternoon of 25 November, Allan Cameron’s 3rd Battalion, which was under Eather’s command, entered the fray. It attacked from the southwest, only to be held up by the same withering enemy fire, and it too withdrew. Clearly, Gona would not be an easy nut to crack.

On 21 November, the 2/4th Field Ambulance established a main dressing station (MDS) in a clearing at Soputa, about 10 kilometres inland, where Major General Vasey’s 7th Division had just moved its headquarters. Here doctors and medics treated the casualties of the fighting at Gona and Sanananda. They had no shortage of patients; despite the flatter terrain, hell’s battlefield had few hotter corners than here on the Papuan north coast.

Six days later, thirteen Japanese Zeros bombed and strafed the dressing station, the divisional headquarters, and the US 126th Combat Clearing Station nearby. Among the twenty-two Australians killed were Majors Ian Vickery and Hew McDonald, of the 2/4th Field Ambulance. The destruction was horrific. Sergeant Alan Sweeting wrote, ‘When the attackers had left the area the hospital was a shambles of mangled limbs and bodies.’ One man was carried out with his leg hanging by a shred. ‘Thank Christ that’s happened,’ he quipped, ‘I won’t have to scratch the bastard anymore.’3 Though a red cross sign had been spread on the ground, the MDS was only 100 metres from the headquarters and within a few metres of a road carrying military traffic. A few days previously, a jeep towing a 25-pounder gun along that road had stopped beside the dressing station, taking cover as a Japanese reconnaissance plane flew over. At the American clearing station, only 250 metres from the MDS, five Americans were killed. The large white cross on the ground had been removed the day before the bombing after planes mistakenly dropped supplies onto it. After the war, this case was not presented to the United Nations commission into Japanese atrocities. While the consequences were appalling, the circumstances made it arguable that—unlike the massacres at Tol Plantation and elsewhere—the attack on Soputa was not a deliberate war crime.4

On 25 November, General Blamey attended a conference at General MacArthur’s headquarters. Concerned by the failure to rapidly seize Gona and the other beachheads at Sanananda and Buna, MacArthur suggested sending in the US 41st Division. Having already witnessed the failure of the US 32nd Division at Buna, Blamey said he would rather put in more Australians, as ‘he knew they would fight.’5

That same day, the first units of 21st Brigade were flown into Popondetta, about 20 kilometres inland. It was a brigade in name only. Ravaged by the Kokoda campaign, it had no more troops than an average battalion. Lieutenant Colonel Geoff Cooper’s 2/27th had three weakened rifle companies of about eighty men each, A and B companies having being merged.6 Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Challen’s 2/14th made a similar adjustment, using D Company to reinforce the other three.7 The brigade had a new commander, Brigadier Ivan Dougherty, who had served as a battalion commander in the Middle East and then in Darwin under General Herring. The new command structure—from Dougherty up through Vasey to Herring and Blamey—was designed to ensure that Blamey’s orders were followed. Blamey was out to show MacArthur that Australian troops would fight. But the brigade he had disparaged with his words at Koitaki would soon be destroyed by his orders at Gona.

At 0700 on 28 November, General Vasey passed on to Dougherty the order that Gona Mission was to be taken the following day. To this end, the 2/14th and 2/27th Battalion were moved up to the front lines from Soputa, a tough day’s haul. The rush left no time to go over the lay of the land or even to give the men a briefing from the 25th Brigade troops who had already been up against the enemy defences. Though both Dougherty and Vasey requested a delay, Herring and Blamey insisted that the attack go ahead. A convoy of Japanese reinforcements was on its way from Rabaul. Also, while Buna and Sanananda were mainly American affairs at this stage, Gona was an all-Australian fight. Lives were to be sacrificed to prove a point; a bitter trade.

Herring and Blamey had quite a point to prove. Next day, they intended to confront MacArthur with evidence that Major General Edwin Harding, the American commander at Buna, had been unable to get the US infantry to attack; in their view, Harding was unsuitable for command, and the capture of Buna was beyond the ability of his division. In light of this, Blamey knew that the commitment of his Australian troops had to be total. Despite what he had said at Koitaki, or perhaps because of it, he also knew that the 2/14th and 2/27th infantrymen would either carry out the diabolical task he had set or die trying.

Challen’s 2/14th was to make the first attack, with the 2/27th in support. But heavy clashes began almost immediately, as the weary soldiers of the 2/14th moved into supposedly unoccupied jumping-off positions on the coast east of Small Creek, between Gona and Basabua. Dougherty had played his part, ordering the troops up before patrols had given the all-clear.8 It would not be the last hasty decision made during the fight for Gona, and each such decision would cost more lives. Major Phil Rhoden noted that ‘casualties went all night.’ Captain Charles Butler, in charge of C Company, was badly shot up down one side. As he was carried out, he joked to Rhoden, ‘It looks as if I’ll be one-eyed now; no use me going to the football.’9 The eleven men of the 2/14th who died that night were only the first of many that the brigade would lose. The next day the survivors pressed towards Small Creek. Captain ‘Mocca’ Treacy, who had taken over A Company, was killed at the head of his men.

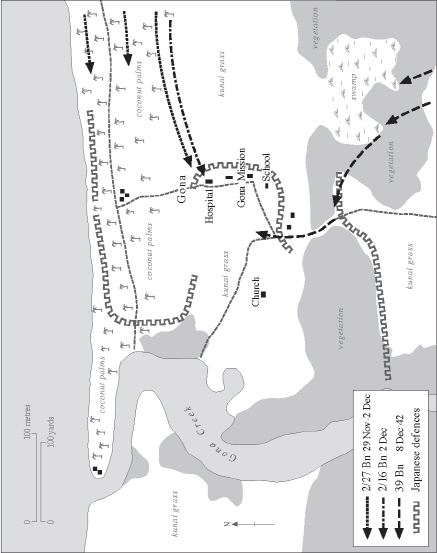

Gona: 29 November–8 December 1942

With the 2/14th prematurely engaged, the 2/27th now faced an even more daunting task. At midnight, Dougherty ordered them to attack the Japanese perimeter at Gona the next morning, 29 November. The 2/27th adjutant, Captain ‘Harry’ Katekar, was dumbfounded, and for good reason: the battalion had no information about the nature of the defences or the attitude of the defenders in Gona. Though aerial photographs existed, none was made available. All the men had were some rough sketch maps. It made no sense at all to attack under such conditions, without even a contact patrol to fix the location of the enemy defences. As Katekar summed it up: ‘We were pretty innocent, like babes, going into that attack.’10

Two companies would move to the coast. From there, Captain Charlie Sims’ A Company would attack along the beach and among the coastal coconut groves, while Captain Jack Cuming’s C Company advanced on the left, through the kunai grass. The troops stepped off at 1000, halted for half an hour at 1030 to get their bearings, and moved off again at 1100 as a supporting air attack dropped about seventy bombs across the Japanese perimeter. Cooper later noted that the bombing was not particularly effective: within five minutes of the last bomb being dropped, all the defenders would have been ready and waiting for the ground attack.11

Ten minutes of artillery support from four 25-pounders of the 2/1st Field Regiment followed at 1145. Major Arthur Hanson, who had come up to act as the forward observation officer, had his problems. It took him quite some time to find Colonel Cooper, whereupon he discovered that nobody knew where the enemy machinegun posts were that had stopped the earlier attacks. With a limited number of rounds available, Hanson could only direct the artillery fire into the general area. As Cooper later observed, with such limited support, ‘You can’t blow down Troy.’12

For the men of Sims’ and Cuming’s companies, the going was slow, but they finally reached the coast at 1215. The two companies then swung to the left, moving parallel to the beach. Lieutenant Bob Johns had earned a field commission since Kokoda; now he led his platoon forward through the sparse scrub and kunai behind the beach. His was the point platoon, deployed in arrowhead formation with two forward scouts. Lieutenant Peter Sherwin’s platoon was to Johns’ left and further back, Lieutenant John ‘Jo’ Flight’s to his right and also behind. The artillery barrage ended, and all was quiet: the Japanese defenders maintained excellent fire discipline. Then they opened fire. It was like ‘a murderous curtain of lead.’13

While Blamey’s demands prevented a well-planned Australian attack, the defensive tactics of the Japanese commander, Major Tsuneichi Yamamoto, were straight from the textbook. As Harry Katekar later observed, the enemy fire plan had four dimensions. Heavy machinegun posts on both flanks of the defensive line fired on fixed lines across their front, catching the attackers in a deadly crossfire. From their trenches and other positions, the Japanese infantrymen added rifle and light-machinegun fire. Snipers up in the palm and banyan trees added to the deadly mix, finding even better targets once the attackers went to ground. The enemy’s defensive perimeter extended about 300 metres inland, with the positions near the beach only 5 metres apart. The strongest posts were dug in under the roots of large banyan trees, spitting deadly fire from the shadows.14

Many men were cut down in the opening barrage. As Johns hit the deck, his first thought was that he had no idea where the fire was coming from. Then a call went out for the platoon commanders to get back to Sims’ company headquarters. Sims told platoon leaders Flight and Sherwin to make leapfrog attacks through Johns’ platoon, which would provide supporting fire. As Johns and Flight zigzagged their way back to their platoons, Flight went down, shot through the chest. Turning him over, Johns saw a massive exit wound; he was already dead. Johns then called across to Flight’s sergeant to take over and told the forward Bren gunner to get into position to support the attack. As the gunner moved to a small knoll, he was shot and killed; his replacement suffered the same fate.15

With Flight dead, his platoon faltered. When Sherwin got up to lead his platoon forward, he too was shot down, badly wounded in a leg he would later lose. Behind a coconut palm, big Paul Robertson stood tall, firing back steadily before also being shot. Johns then went out for the Bren gun. ‘Then slam, like being hit by a barn door, I collected [a hit] myself,’ he later recalled. ‘Set me back like a shot rabbit.’ Johns had been wounded in the right shoulder. His batman, a pace behind him, was killed by the same burst of fire.16

To the left of Sims’ shattered company, Cuming’s men had moved through kunai grass until they got 50 metres further on than Sims. The forward units passed several advance Japanese foxholes that were quickly dealt with. Then a halt was called, and Ray Baldwin was sent back to Captain Ron Johnson, the battalion 2IC, to get permission for Cuming to attack the beachfront positions at right angles to Sims’ beleaguered A Company. Cuming planned to attack the main enemy position confronting Sims by advancing across A Company’s front.17

At 1530, Cuming led his men in with the same spirit the men on the coast had shown. But spirit had no power against Japanese bullets. Cuming and his 2IC, Captain Justin Skipper, were both killed as they led the assault on the seafront bunkers. Ray Baldwin heard Skipper’s last call, ‘Come on in, 13 Platoon, attack, attack,’ and also saw Jack Cuming cut down as he stood atop a strong post with rifle and bayonet, inspiring his men. The attack broke down in the face of the Japanese machine guns concealed under the banyan trees. Anything moving on the ground was a target. As Baldwin observed, ‘Fire was coming from so many places, it was difficult to pin any one exact location.’ Just as telling as the firepower was the defenders’ resolve. ‘The Japanese were maniacal,’ said Baldwin, ‘they were screaming their heads off.’ With the kunai grass burned, there was also little cover. Baldwin sheltered behind a fallen palm tree until two grenades went off near his head. Covered in blood, he made his way to the rear, where he later had a dozen pieces of shrapnel extracted from his body.18 Fourteen Australians died during the 2/27th’s attack, including three officers. Another forty-one wounded men lay out in the afternoon heat; at least one later died.19

That evening, Herring wrote to Blamey. Progress, he reported, had been steady but slow against a centre of resistance east of Gona Mission, but Vasey ‘does not think it very formidable.’ He added that Dougherty handled his troops well and that the 2/27th would seize the mission at first light next morning.20

Despite the failures and losses, the 2/27th would indeed make another attack, on 30 November. It would be just inland from the beach, on a 100-metre front, this time using Captain Tom Gill’s D Company. Two platoons would go forward, the one on the left making its way among the coconut palms; the one on the right through the kunai. At least Gill’s men knew where the front line was: most of the dead bodies from the previous day still lay out there. A newly arrived company from the 2/16th Battalion, under Captain John O’Neill, would support the attack on Gill’s left flank. O’Neill’s company, only seventy men strong, would go in blind, with only the sketchiest idea of the terrain or the nature of the defences.21

Gill attacked at 0615. The men from Lieutenant Sid Hewitt’s platoon, on the left flank, advanced through the two-metre-high kunai grass until they reached a burned-out patch. This scorched earth was the killing ground the Japanese had prepared in front of their positions. Bert Ward later observed, ‘As soon as we emerged from the limited cover of the scrubby trees we encountered this wall of fire.’ To Ward, it was ‘like being attacked by about a hundred swarms of bees.’ Hewitt’s men promptly returned to the cover of the kunai. Ward, a Bren gunner, had been concerned before the attack that he had only five magazines, including the one on the gun. He wanted to spray the tops of the palm trees for snipers but knew he had to keep most of his ammunition for the attack on the strong posts. A short time after he went to ground, a sniper wounded him and he crawled to the rear. He had still not seen an enemy position, let alone a Japanese soldier.22

On the right flank, closer to the beach, both Tom Gill and one of his platoon commanders, Lieutenant George MacDonald, had been wounded, two of twenty-five casualties taken by D Company during the attack. The artillery laid down a smoke screen so the wounded could be recovered before A and C companies moved up to continue the assault under the cover of 3-inch mortar fire. This attack also failed, and there were another thirteen casualties, including the A Company 2IC, Captain Teddy Best, who was killed.23 Blamey’s butcher’s bill was rising.

It was horrific stuff, akin to some of the senseless charges of the First World War or the American Civil War. Yet despite the failure of the 2/31st’s initial assaults, the Australian tactics didn’t change. That night, George Vasey wrote to his wife, ‘I had no idea the Jap, or anyone, could be as obstinate and stubborn as he has proved to be . . . He simply has to be dug out and killed and that, unfortunately, is a slow and expensive process.’24

Just after midnight on 1 December, the Japanese tried to land three barges in the Gona perimeter but were driven off by Australian fire. Enemy reinforcements landing on a narrow strip of beach could be dealt with; entrenched defenders were a different matter. Now, with all three of Cooper’s frontline companies broken, a secondary drive was ordered further south, using O’Neill’s 2/16th company and troops from Cameron’s 3rd Battalion. Though under 25th Brigade command, Eather had agreed to the use of the 3rd on the left flank of Dougherty’s latest attack.

The rumps of Cooper’s three companies would again be sent against the perimeter. Another company of the 2/16th, under Major Albert Robinson, would serve as the battalion reserve once it arrived that morning. The attack would be preceded by nine minutes of artillery fire and take place under a smoke screen laid by Captain Bob Clampett’s 3-inch mortar platoon. A Vickers machine gun had also been emplaced to fire along the beach. Again, the attackers closest to the beach took heavy casualties, including Cooper, who was wounded and evacuated.

In the centre, Lieutenant Bill Egerton-Warburton took D Company in. Sergeant Roy Thredgold told his corporal not to go under fallen trees: the day before, two men had been killed by an enemy machine gun that was set up to target one such position. Despite Thredgold’s warning, the corporal let two fellows crawl under the same tree, with the same result: two more deaths. ‘We are going into a death trap again,’ Thredgold told his men. ‘Keep five yards apart.’ But in a misguided effort at self-protection, the troops started to clump around their sergeant as they moved forward. ‘For Chrissakes, spread out,’ he told them again.25

The men moved out across the burned kunai patch, knowing it was an ideal killing ground. ‘Bare as a baby’s bum, this stubble paddock,’ Thredgold later said. He knew that, as a Tommy gunner, he would be one of the first targets. Sure enough, he took a bullet through his leg in the opening burst of fire. He handed the Tommy gun across to the next in charge, ‘Benny’ Sparkes, and the men moved about 200 metres across the stubble into the kunai on the other side. Thredgold managed to get into a shell hole, and soon after midday the forward troops came rushing back. When it got dark, Derrick Parsons organised a stretcher to carry Thredgold out. His war was over.26

O’Neill made good progress on the left. Inside him on the coastal side, Lieutenant Harold Inglis’ 16 Platoon, from the 2/27th, also reached the mission, but that progress came at a cost: only three men made it. Inglis was among the fallen. Unfortunately, no support came from 3rd Battalion: Cameron’s men, to the south, failed to see O’Neill’s company. That was not altogether surprising, since the troops passed each other in the pre-dawn light and the kunai grass in some places was more than two metres high.27 Cameron contacted 2/27th headquarters at 0645, stating that he could not see the advancing troops and would therefore not advance his men. Thus the chance to close up the line and put in enough infantry to hold Gona was lost.

When Robinson’s reserve company finally attacked at 1040, the men took an enemy post, but the Japanese counterattacked and evicted them. Robinson was wounded in the fighting. Denied support when he needed it, O’Neill now had the added problem of being bombarded by the Australian artillery, which was unaware of his location. Though his men were in a trap, the badly wounded O’Neill and some of his men managed to get out by crossing Gona Creek and meeting up with some men from Chaforce—a composite force of 21st Brigade men—on the western side. The dying O’Neill was left on the eastern bank of the creek. One of O’Neill’s platoons, led by Lieutenant Leo Mayberry, had been down to six men when it reached Gona Mission, and then lost two more getting out.28 That same night, Tom ‘Pinky’ McMahon and Ernest Yeing, both 2/16th men serving with Chaforce, swam the creek and brought O’Neill out on a punt, passing within 20 metres of an enemy post. The following night, McMahon went back and destroyed that post with grenades.29 The gallant O’Neill would die from his wounds a few days later. The two 2/16th companies had given their all, as the fifty-nine casualties clearly showed. That night, Herring wrote to Blamey, telling him that a liaison officer sent to the 2/27th had reported that, ‘He thinks 2/27 slightly shaken by measure of resistance encountered.’30 Slightly shaken! Herring’s orders had destroyed Cooper’s battalion.

On 3 December, the Australian cameraman George Silk visited the 2/27th lines at Gona. Silk wanted to photograph the Japanese dead heaped in their defence positions. This, he was told, he could certainly do—once Gona fell.31

The Japanese command had no intention of relinquishing the Papuan beachheads. The 21st Independent Mixed Brigade, under the command of Major General Tsuyuo Yamagata, had been brought to Rabaul from Indochina. After Allied bombing turned back the initial destroyer convoy sent to Gona at Vitiaz Strait, a second convoy of four destroyers left Rabaul on 30 November via the more direct southern route. The convoy carried three companies of Major Tsunezo Iwasaki’s III/170th Battalion, some 500 men in all. Despite having a fighter escort, the destroyers were attacked by Allied aircraft on that afternoon and also that night, as they approached the landing points. The ships dispersed but later returned to the mouth of the Kumusi River, where their landing craft unloaded a total of 300 troops, those unable to get off returning to Rabaul.32 Another fifty men landed west of Gona in the early hours of 3 December and waited until dusk before heading for the mission in a small boat. The landing craft ran out of fuel and another small boat was sunk, but by the morning of 6 December, 300 men had gathered under Yamagata, some wearing nothing but loin cloths. Though stragglers from Gona reported that the mission had already fallen, Yamagata directed his force east, towards it.33

At the height of the Kokoda campaign, the composite Chaforce had been formed from the fittest remaining men of 21st Brigade. Colonel Challen, after whom the force was named, had taken about 400 men back across the Kokoda Trail with the aim of getting behind the Japanese lines. The swiftness of the Japanese retreat had prevented that, and Chaforce had been deployed west of Gona Creek since 21 November. By that time, Challen had been transferred to the command of the 2/14th Battalion.

By early December, Chaforce was down to forty-five men, all of whom had been fighting since August. They had crossed the Kokoda Trail three times before spending the last two weeks watching the Australian left flank. A small band of them were led by the irrepressible Lieutenant Alan Haddy, who had been through thick and thin with the 2/16th, from Syria to the Owen Stanleys and now at Gona. Haddy had kept these men going; natural leaders like him were the backbone of the Australian Army. On 1 December, Haddy and twenty men held a small coastal village about three kilometres northwest of Gona Mission and just east of the Amboga River, later known as Haddy’s Village.

Around midnight on 6 December the Japanese came, their approach masked by the incessant rain. One of the Australian sentries, Syd Stephens, was killed by a grenade as the attack started. Hearing the fighting, Chaforce headquarters kept trying to contact Haddy by phone, but each time it rang the enemy would hear it and throw grenades. Haddy finally disconnected it and then sent Charles Bloomfield and three wounded men back to get help. Though weakened by malaria, Bloomfield carried one of the wounded men on his back. The rest soon followed, ordered out by Haddy, who decided to remain to the end. His body was later found surrounded by spent cartridges and enemy corpses; he had been game to the last. Three months earlier, during the desperate fighting atop Brigade Hill, he had told his acting company commander, ‘You can’t live forever, boss.’34

Back at Gona, Colonel Honner’s 39th Battalion had moved into the front line on 4 December, replacing Eather’s weakened brigade on the inland side. As at Isurava, once more the 39th would fight alongside the 21st Brigade. Captain Max Bidstrup’s D Company was ordered to make the first attack on 6 December, going head-on against Japanese defences between the main track and Gona Creek. The two platoons making the attack were supported by mortar smoke rounds, but after gaining 50 metres, the men emerged from the smoke onto an open killing ground covered by well dug-in enemy positions. The machinegun crossfire from either end of the line badly cut up the platoons, killing twelve men and wounding forty-six. Arch Skilbeck showed great valour, going forward four times to bring wounded men out. Once darkness fell, men from Reg Edgell’s section on Bidstrup’s right flank penetrated the enemy posts and reached the timber on the outskirts of Gona. Edgell, armed with his Owen gun, and a Bren gunner attacked one of the posts, killing about a dozen Japanese.35 This exploit suggested how the defences might be breached.

The next day Honner was ordered to make another frontal attack and an attack east of the track. Despite the addition of some air support, Honner knew he had little chance of success and would once again lose valuable men. He watched as the air attack went in and saw that no bombs had struck the enemy positions. Thinking fast, he called brigade headquarters and requested a delay, saying the aircraft had forewarned the Japanese. He told Dougherty to keep the aircraft away for the next attack and asked for properly coordinated artillery support to give his men a chance.36 Honner was also given the opportunity to pick his spot. He decided to send Captain Joe Gilmore’s A Company in on the right side of the track, towards the area that Edgell had found, where a patch of jungle provided some cover at the edge of the enemy defences. The surviving D Company platoon would follow up to exploit any breach. Still under orders to make another attack between the track and Gona Creek, Honner told the C Company commander to have his men fire their weapons to hold the attention of the Japanese, but not to advance.37

That day, one of the Japanese defenders—who, like his adversaries, had already served in the Kokoda campaign—made the last entry in his diary. ‘Shells dropped near us like rain,’ he wrote. ‘It was only through the protection of the gods that we were safe . . . everyone expected to die at any moment.’ His moment would come the following day.38

On that day, 8 December, a heavy artillery and mortar barrage began at 1230. The plan called for the four 25-pounder guns to fire for fifteen minutes. But with 200 shells available, at three per minute per gun, there were enough rounds for an extra two minutes’ bombardment.39 Believing that his troops were better off risking a hit from the bombardment than being caught out in front of the machinegun posts, Honner arranged for the extra two minutes without informing the attacking platoons. They would form up 100 metres from the defences, a distance they should be able to cover in the first extra minute. They would then have another minute of support as they assaulted the strong posts. Honner also asked that the artillery shells be fused to burst once they had penetrated the soft soil so as to shake up the defenders and damage their dug-outs.40

Unknown to Honner, Lieutenants Hugh Dalby and Hugh Kelly, the commanders of the two assault platoons, had already decided to move off one minute early, at 1244. That way, when the barrage lifted, they would be within 30 metres of the defenders. This they did. Dalby checked his watch, and at 1245 he rose with his men to charge that last 30 metres. Just then the 25-pounders opened up again, and everyone dived to the ground as the salvo crashed home close in front. Dalby and his men rose again and charged. Again the guns crashed; again the men hit the dirt as the explosions rang out around them.41 Two men were wounded by the shellfire, but as Joe Gilmore later observed, ‘If we had not followed up so close, we wouldn’t have got through at all.’42

When the men got up again, Dalby realised that their two charges had brought them up to the defences. The Japanese were crouched in their weapon pits with their heads down, and that is how they died. Dalby was first in. He killed seven of them, including a Juki machinegunner whose position had been pinpointed before the attack. The shellfire had also stripped the camouflage from the weapon pits, and three other machinegun posts were quickly despatched and thirty-eight Japanese killed.43 Stan Ellis moved through the timber, wiping out another four enemy posts. It was not all one way; on the right, gunfire from positions around the mission hut killed three or four men in Kelly’s platoon. Under sweeping fire, ‘Darky’ Wilkinson mounted his Bren gun on an old fence and let loose, silencing the enemy post.44 Honner now put C Company into the breach to follow up. The 39th infantrymen spent the afternoon clearing their way through the Japanese defences and reached the beach: they now occupied half the perimeter. Honner then signalled Dougherty: ‘Gona’s gone.’45

That same day, Major Frank Sublet had taken over command of the remnants of 21st Brigade east of the perimeter. According to Sublet, the man he replaced, Lieutenant Colonel Albert Caro, had been dismissed after expressing his concerns over casualties to Dougherty. Dougherty told Herring that he had no confidence in Caro and that he was to be sent out.46 Harry Katekar, who had seen the 2/27th bled white, was not impressed with Sublet: ‘He was a gung ho type, and we would have to throw every man we could lay our hands on into further attacks.’47

Once it became apparent that the 39th attack had broken into the perimeter, Sublet lined up three Bren gunners behind a mound and had them spray the treetops for snipers. The Brens fired thousands of rounds, and the barrels had to be changed regularly.48 Sublet then ordered his remnants, two weakened companies of the 2/27th and 2/16th, each of about fifty men, to attack the beachfront positions again. Leo Mayberry took six men with him and charged a strong post. Seriously wounded in the right arm, he was unable to throw a primed grenade and had to force the pin back with his teeth.49 The other two platoon commanders from the 2/16th were also hit, Lieutenant Leo Inkpen mortally so. The company from the 2/27th managed to get into one of the strong posts, at the cost of eight men killed and eighteen wounded, including Captain Ron Johnson and Lieutenant Sid Hewitt. If General Blamey was looking for more 21st Brigade officers to berate for their performance after this battle, he wouldn’t find many available. Harry Katekar later observed, ‘I think a lot of the casualties that occurred at Gona were to an extent suicidal.’50 Still, that night it was the Japanese who ran like rabbits.

Harry Katekar was the last surviving officer of the 2/27th, but he might not be for much longer. Sublet decided it would be a good idea for him to lead a night attack to take another strong post on the beachfront. It was approaching midnight and pitch dark as Katekar gathered the last few men around him only 5 metres from the enemy post. When one of them cried out that he had been stabbed, Katekar told him to shut up, thinking he must be still half asleep and shaking off a nightmare. Then he looked out to sea. Enemy troops were moving through the water and along the beach, heading east in an attempted breakout towards Buna. Katekar’s men opened fire, and the Vickers gun further back soon joined in.51

‘Halt, password,’ Les Thredgold called, before dropping two of the fleeing Japanese with his Tommy gun. After a few rounds, the gun stopped firing and Thredgold’s training (the men would compete to see who could clear stoppages fastest) kicked in. He cleared the round, slapped on a new magazine, and at a range of only a few metres, cut down six more enemy soldiers, including an officer. But from the officer’s direction Thredgold heard a little click . . . and then another. Thredgold fired again, shattering the officer’s helmet. He later found the officer’s rifle: the bolt was pulled back, but the gun had not been fired. Thredgold now felt he had helped balance the ledger for his two brothers, who had both been wounded at Gona.52

The next morning, 9 December, ninety-one enemy bodies lay around the beachfront position and another twelve were found further along the coast. All had been killed in the breakout. Others had got out further inland. Then came the grim task of clearing away the dead. Many were found wearing gas masks. Some Australians thought that might have been because they were expecting a gas attack—until the stench rose. The Japanese hadn’t bothered to bury their dead during the battle and in some cases had even used the bodies as fire steps, standing on them for better aim.53 The Australians buried 638 of them, though more still lay out in the kunai grass and along the creek.54 Honner observed, ‘It was sickening to breathe, let alone eat.’55 The Salvation Army officer Albert Moore wrote of ‘hundreds of Jap dead in all stages of decomposition from skeletons to newly killed men. Many Australians amongst them.’56 The malaria-ridden Australian troops, who had hung on in the front line, now staggered back to the RAP. Most of the others hobbled around with bandages on their raw feet. George Silk came through that afternoon and got his photos.

There were still Japanese forces to be cleaned up west of Gona. Honner’s battalion was sent off to support the remnants of the 2/14th Battalion, who were holding firm against a Japanese push east from Haddy’s Village. The additional troops advanced through the scrub inland from the coast, then entered Haddy’s Village from the south. Though they did not enjoy complete surprise, they did enough to stymie any Japanese plans to move on Gona Mission. With fighting continuing at Sanananda, Gona was now garrisoned by only one officer and four men. Troops were that short.57

On 23 December, Sublet wrote a letter setting out the condition of the broken force he now commanded. Following on from the trials of Kokoda, the fight for Gona had all but crucified 21st Brigade. Almost all of the experienced officers and NCOs were now dead, wounded or sick. The 2/16th Battalion was down to eight officers and eighty other ranks, of whom twenty-four were under medical treatment. The 2/27th had only three officers and eighty-seven men, with seventeen under treatment. Few trained riflemen remained, and men were being put under arrest for refusing to patrol. Vasey saw the report and went in to bat for Sublet.58

The Australian commanders were also under enormous pressure, though not for their lives. The failure of the American troops at Buna had meant that the strongest Australian brigade, the 18th, had to be sent there. Similar failure at Sanananda had drawn in Lloyd’s 16th Brigade, Porter’s 30th Brigade, and the 2/7th Cavalry Regiment. There was no relief for 21st Brigade until 6 January, when the wasted remnants marched back to Dobodura. They were then flown to Port Moresby, where the rebuilding could begin. For Dougherty, it had been a rough introduction to front-line brigade command. He later told Official Historian Gavin Long, ‘If I’d had a tank, even a light tank, it would have saved 200 lives.’59