3

The Light of the World

Hermeticism, Renaissance Neoplatonism, and the theory of operative magic were the intellectual currents Dee had immersed himself in beyond his already comprehensive scientific and mathematical studies. In the 1550s, Dee began to synthesize what he had learned, and began to produce his own original works that drew together his immensely broad studies.

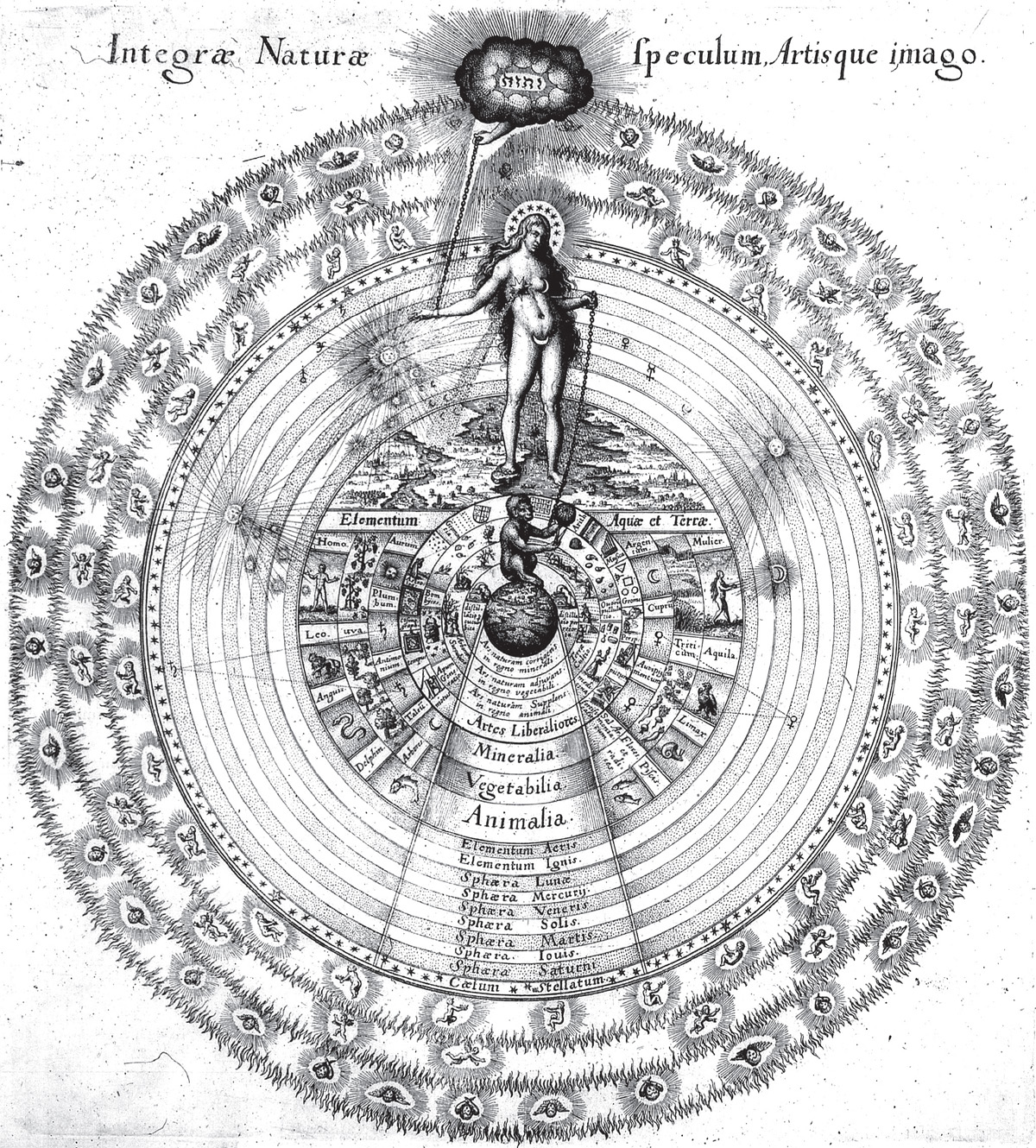

In extrapolating the ideas and methods of Roger Bacon, Agrippa, and others, Dee had isolated the first key to the Great Work. From these sources, he had learned the doctrine that subtle forces emanate from all things in nature; for instance, that the planets and stars exercise subtle influence upon events and the character of individuals, which is the theoretical basis of astrology. All things, in the Hermetic worldview, expressed their energy or vibration outward, and impressed it on the objects around them. Not content to just assume the existence of such “rays” of influence, Dee looked to apply his vast astronomical, mathematical, and optical knowledge to observing and manipulating these rays.

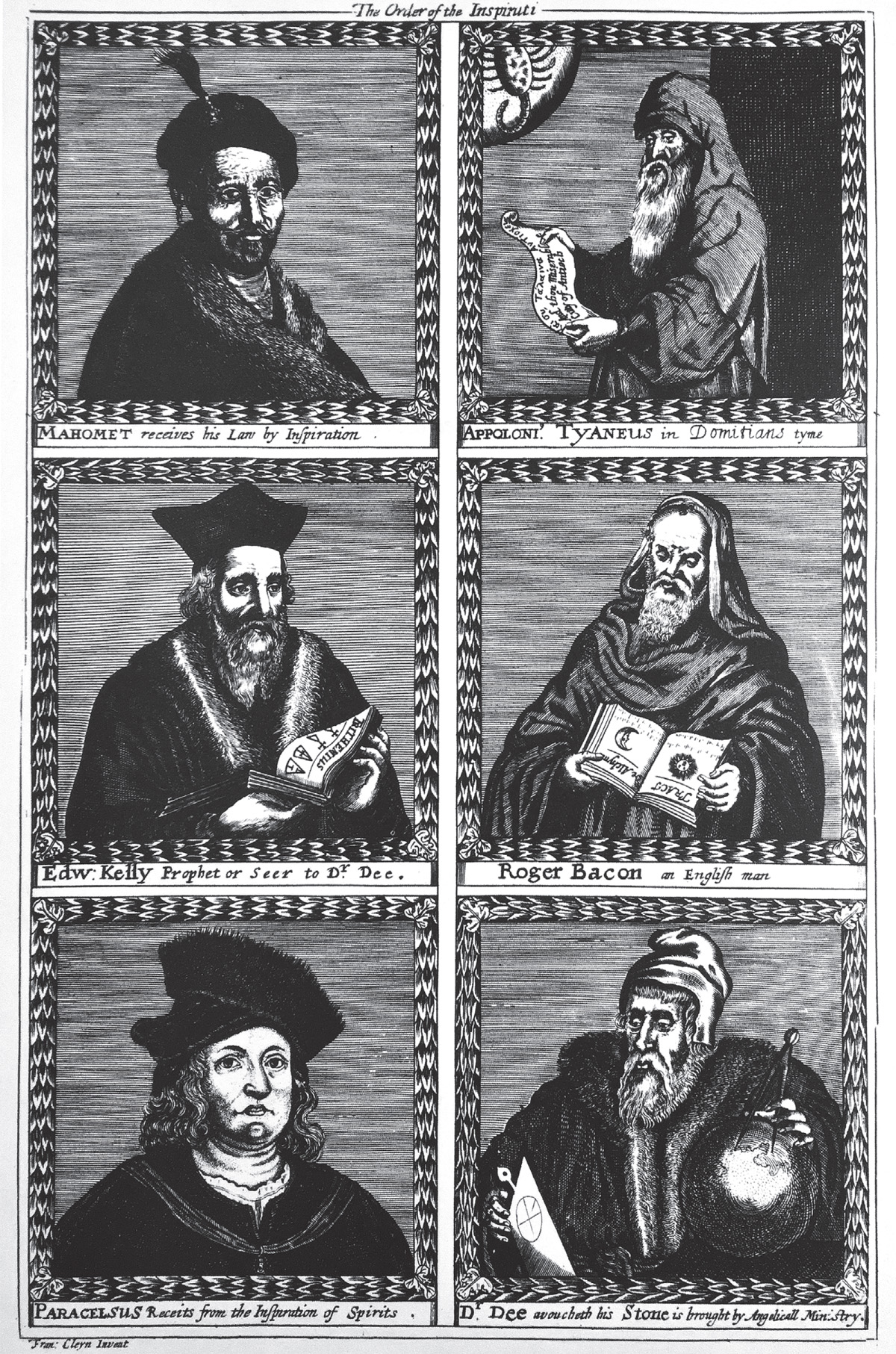

What Dee was proposing was that, just as the telescope would one day show us the distant planets and stars, and the microscope would one day show us the hidden world of microscopic objects, optics might also allow us to tangibly see the hidden spiritual forces of reality. Instead of a telescope or microscope, Dee used a scrying ball as his instrument. Within this device—which survives in popular culture as the crystal ball of fortune-tellers—Dee hoped to study the stellar rays of creation, in direct or indirect sunlight, within precise astrological timings and ritual parameters.

Instrumental to Dee’s theories was the tract On the Stellar Rays by the Muslim Hermeticist Abu Yūsuf Ya‘qūb ibn ’Isḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī, who Bacon thought second only to Ptolemy in his knowledge of optics.1 Al-Kindī had written not only of the effects of the light emitting from the stars and planets upon consciousness, but the rays of will and imagination emanating from individual human beings. For al-Kindī, it was the stellar rays that formed the destinies of men, not acts of will, even if magically directed. The rarest of men, however, could overcome their mortal bondage by working with the rays of light emitting from the stars.2

Fig. 3.1. Frontispiece to John Dee, Propaedeumata aphoristica, featuring the Hieroglyphic Monad and Tetragrammaton.

This idea fired Dee’s imagination, as it would allow him to merge his technical mastery of optics and his metaphysical study into the beginnings of what he hoped could be a hard science. The product of Dee’s investigation is 1558’s Propaedeumata aphoristica, a treatise that mathematically and scientifically examines the astrological influences on Earth—at a time when astrology was in decline in England, and ephemerides had to be imported.3 Dee presented it as the fruit of his previous ten years of “Outlandish & Homish studies and Exercises Philosophicall.”4 It is likely that Dee, horrified by his treatment under Mary’s regime and probably thinking back to the offers of employment in France that he had turned down (only to be imprisoned and tortured in his home country), published the Propaedeumata with an eye toward seeking new benefactors abroad, and establishing himself not only as a mathematics teacher but as a philosopher. Dee dedicated the tract to Mercator.

In the Propaedeumata, a youthful and infectiously enthusiastic Dee outlines his cosmological view, which resonates greatly with al-Kindī. For Dee, all things in the universe emit rays in all directions according to their nature; these rays have different effects based on what they contact, but all things in the universe are simultaneously affecting all other things. These rays have influence not only upon the material world, but upon the soul, as in astrology; the universe is therefore made up of both elemental and celestial influences.

By studying the influence of the celestial rays on the sublunary, elemental world, Dee sought to understand the subtle machinery by which God, the Monad, manifests the Creation. Light had been the first creation of God—fiat lux, “let there be light”—therefore, as Bacon had suggested, understanding light would be the key to understanding everything.5

Unspoken but implied is that operative magic such as Agrippa’s may be used to harness such rays: “In actual truth,” says Dee, “wonderful changes may be produced by us in natural things if we force nature artfully.”6 Through the proper use of optics, the celestial rays might be concentrated, manipulated, or even stored, producing focused effects far beyond what already occurred in nature. Rays harnessed in this way, Dee later mused, might even assist in alchemy.

“If you were skilled in ‘catoptrics,’” Dee explains in the Propaedeumata—catoptrics is the use of mirrors—“you would be able, by art, to imprint the rays of any star much more strongly upon any matter subjected to it than nature itself does.”7

By gaining such insight into the system of the world, and its natural harmonies and antipathies, Dee suspected that the natural philosopher or magician could come to participate in nature as a cocreator. This would fulfill the goal of Hermeticism, that through study, experiment, piety, and observation of nature, a natural philosopher could understand the system of reality and how God perpetually manifests the universe—that is, they could become initiated. Once this understanding was gained—and only when it was gained—could the magician develop the wisdom necessary to work with the system and cocreate alongside nature and God.

Such a “pure” magic relied not on trance, spirit conjuration, or anything recognizable as archaic shamanism or ham-fisted grimoire magic; rather, it consisted of the physical manipulation of light. Like Agrippa, Dee sought to work with the subtle forces of nature, but uniquely aimed to replace superstitious folk magic and ritual incantations with frontline optical technology and mathematics.8 This approach discarded the need for intervention by spirits, thereby cleanly avoiding the charges of demonism that had dogged Bacon, and that Dee sought to deflect from further harming his own career.9 Dee’s synthesis of astrology, mathematics, and optics formulated a remarkably sophisticated operative approach to magic, though the assumptions upon which it rests have long since been discarded by science—for instance, that the stars and planets influence human beings or events.

Magic was only tangential to the Propaedeumata, and is mentioned as only one potential application of Dee’s theories. It was “astral” physics itself that Dee was most interested in, rather than its practical application. His goal in the Propaedeumata was to reform astrology along mathematical lines, and import a higher level of scientific understanding of astrology to England, where it remained a neglected art, from the Continent. Dee’s mentors at Louvain had assessed astrology with as much intellectual rigor as any other study, and Dee longed to kindle interest in the subject at home. For Dee, the Propaedeumata was not an occult work, but a summation of his learning in Europe, fully in line with Aristotelian thought. In looking backward to Bacon and al-Kindī, Dee was also working outside the usual bounds of academic discourse, and along antiquated lines—even for his own time period. Yet despite their reliance on older works, Dee’s theories are unique, standing apart from any purely Neoplatonic or Hermetic strain of philosophy.10

Dee proposes in the Propaedeumata that the universe is created by God from nothing, contrary to any rational or natural law, meaning that the universe can never cease to exist except by God’s agency. However, the Creation itself is governed by rational and natural law, without exception, meaning that no supernatural agency is possible within nature. Within the universe, all is interrelated, and everything within nature influences everything else by means of rays. The universe and all of its perfect harmony and regularity of its stars and planets, according to Dee, is most like a lyre.11 Natural philosophers could play this lyre, working with nature’s laws to achieve effects that the less educated might perceive as magic.

For the sixteenth century, this is a remarkably nonsuperstitious view of the universe, in which it is portrayed as a vast machine. Though Dee’s magical views did not hold up, his portrayal of a mechanistic and ordered universe was a forerunner of works to come, like Newton’s Principia mathematica. Dee was even aware of the already circulating idea that objects of different weight fall at the same speed, generally attributed to the much later work of Galileo.12 His theories are also similar to the Buddhist doctrine of “dependent arising,” or even late twentieth-century chaos theory.

Dee called his new optical science “archemastery,” and believed it would crown all knowledge. Through his methods, the past and future could be divined, visions induced, angels or spirits evoked, and spiritual ecstasy induced in the experimenter. Dee even thought that the harnessing of subtle rays, if combined with the healing art of the physician and the expressing medium of music, could move the world—a knowledge he considered too potentially unsafe to elaborate for the general public in anything other than broad hints.13

Language, too, could operate upon nature through its own subtle rays. Like Postel and Bacon, Dee thought the forces of creation were encoded into Hebrew, although even Hebrew would be an echo of the hypothesized primal language. Following al-Kindī, Roger Bacon had already suggested that words themselves could carry potent occult rays, especially if conveying the soul of the speaker or writer, or suitably charged with the right astrological influences. Parallels could be drawn with the ancient Vedic practice of mantra, the rune songs of pre-Christian Europe, or the mass media and neuro-linguistic programming to come in the future.

Crystal gazing and angel scrying, then widely practiced if not well respected in England, had already appealed to Dee as a tool for political espionage, as well as a source of learning beyond the realms of men. The use of scrying glasses was not new; Paracelsus had recommended contacting spirits by scrying into shining black coal, though he warned that such spirits almost invariably lied. The twelfth-century alchemist Artephius had spoken of the ars sintrillia, the use of mirrors to induce trance. Scrying even appears in Genesis 44, in which Joseph speaks of his master’s silver scrying chalice; divination is later condemned in 2 Kings 21. The level of scientific rigor Dee brought to scrying, however, was new. Yet Dee’s work was theoretical at this point—he would not begin actively exploring scrying until the late 1570s.14

For now, Dee was synthesizing his student learning and formulating the basic theories that would occupy his adult study. Yet Dee’s astrological theories, even if elegant and inspiring, proved unworkable at this stage; after publication, he was even accused of plagiarizing the twelfth-century Italian philosopher Urso of Calabria.15 They would not be accepted by later science—nor, surprisingly, would they even be explored by later occultural movements.

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century proponents of occultism were concerned with subjective experience, rather than objective science—relying on symbols, trance states, suggestion, and drugs to produce profound shifts in the internal consciousness of individuals or groups. Since the end of the nineteenth century, Western culture has relegated magic to the subjective realms of art and psychotherapy, justifying the periodic small outbreaks of magic by suggesting that occult ideas may be inspiring or meaningful in a kind of metaphorical way, with buzz phrases like “Jungian archetypes” used by latter-day adherents of the occult to save themselves from the potential embarrassment of being thought to hold literal stock in ideas now considered invalid by the mainstream. Such modern forms of “magic” have far more to do with psychotheater and bluff than rational attempts to analyze objective phenomena.

Fig. 3.2. The Order of the Inspiritui. From Méric Casaubon, A True & Faithful Relation.

Following William James, it was Aleister Crowley, not Carl Jung, who began the trend of “psychologizing away” occult practices—Crowley’s 1903 essay “The Initiated Interpretation of Ceremonial Magic,” printed in the Crowley/Mathers edition of The Lesser Key of Solomon, suggests that rituals are ways of unlocking nonconscious parts of one’s own mind. Crowley, an erudite and hyperrational student of the occult, was inspired by the “all is mind” theories of Bishop Berkeley and Theravada Buddhism, as well as the many experiments with ceremonial magic, yoga, and drugs he had undertaken in his twenties with his mentor Allan Bennett. Crowley’s essay, published when he was twenty-eight or twenty-nine, at a time when he had already garnered vast experience with practical occultism but had moved on to Buddhism, takes a reductionist sword to magic, explaining that “the spirits of the Goetia are portions of the human brain.”16 Crowley was later to recant this opinion; his Magick Without Tears, written in the 1940s, argues in no small terms for the objective existence of spirits and noncorporeal intelligences such as the ones Dee was later to contact. According to the older Crowley, such beings are not only real, but contact with them may be the only chance for humanity to evolve out of the brutal conditions Crowley saw all around him as Europe passed through the death machinery of World War II.17 (On the other hand, Crowley often couldn’t help himself from hinting that the publication of The Book of the Law had caused both world wars.)

Since operative magic has been discarded by mainstream science, those who wish to preserve its practice have had to look for loopholes in the cultural discourse within which magical practices may maintain continuity of existence. Following Crowley and Jung, that loophole has been the psychologizing of magic, which reduces it to something between art therapy and an encounter group exercise. Others have sought to use pseudoscientific claims or overenthusiastic, often scientifically illiterate interpretations of quantum physics, particularly when promoting products within the sizeable New Age marketplace—for instance, mangling wave-particle duality experiments to suggest that consciousness or even belief itself creates reality, or that quantum entanglement proves the efficacy of sorcery, interpretations that amount to little more than wishful thinking (a phenomenon that the noted skeptic Dr. Steven Novella refers to as “quantum woo”).18

Yet all of this was to come later. For this reason, it is remarkable to look at Dee’s original occult theories in context—there is no psychologizing here, no appeal to subjectivity. Dee was literally proposing that natural philosophers experiment with the divine characteristics of light, and that through its use they would shape nature.

In the same year he wrote the Propaedeumata, Dee also composed De speculis comburentibus, a study of geometry, which would be followed by a 1559 manuscript on mathematics entitled Tyrocinium mathematicum, likely used to teach his ward, Thomas Digges.19

Dee would next set to work on the Cabala, and propose to the world a skeleton key of the mysteries, by elaborating the meaning of the Hieroglyphic Monad, a symbol that Dee included in the Propaedeumata without explication; culturally, he would work to get England caught up with the higher standard of learning he had enjoyed on the Continent. Yet for the remainder of Mary’s reign, Dee kept his affairs cloaked in secrecy, terrified of being taken back to the Tower dungeon should the slightest activity be misinterpreted. His writing during this time, however, was prolific, covering astronomy, optics, and technical works on mechanics, astronomical instruments, and a pulley and cog system for moving heavy weights that would gain wide popular use later in the century.

In the end, Dee was saved by most unforeseen circumstances: Mary’s pregnancy turned out to be an elaborate ruse, albeit a ruse that had nearly precipitated a war. When the pregnancy evaporated, Elizabeth was accepted as next in line for the throne, and the furor over Dee’s treasonous conjuring was simply lost in the shuffle.