5

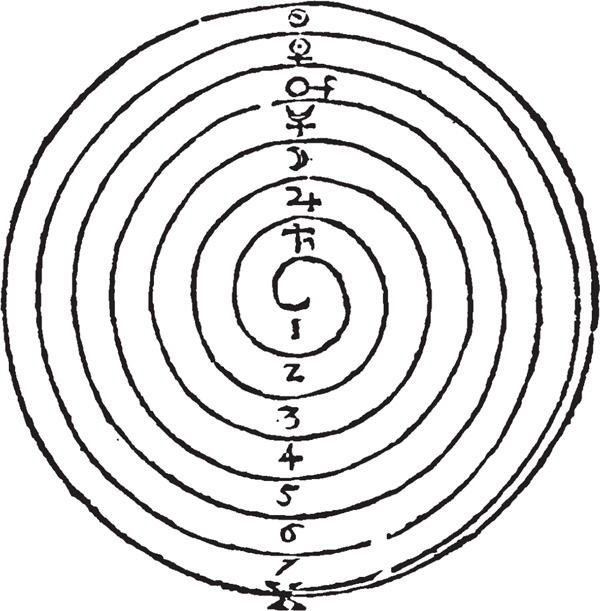

Ladder of Spheres

Dee’s studies were following an increasing arc of complexity. Consequently, he was now looking for methods to categorize and understand larger and larger sets of data.

To the study of Hermeticism and Neoplatonism Dee had now added that of the Cabala, which builds on Neoplatonism’s pure philosophy to provide a working system of categorizing and sorting the universe into a cohesive whole. Broadly speaking, Kabbalah, Cabala, or Qabalah is the branch of mathematics that is concerned with studying the mind of God. Originally a rabbinical tool of scriptural interpretation (as generally spelled Kabbalah), it was synthesized with Christianity, Hermeticism, and Renaissance Neoplatonism in the fifteenth century by Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (as then spelled Cabala).1 Mercifully, it is the structure that brings order to this ideological stack, and draws it together into a cohesive and elegant pattern. Beginning in the nineteenth century, the adepts who predated and then formed the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn changed the spelling to Qabalah (from the original Hebrew, Qoph Bet Lamed Heh), which I will use as a catch-all description in this chapter for sanity’s sake.

While Hermeticism posits the interconnection of all things in the universe, the Qabalah shows what the connections actually are, and forms a metaphorical map of the cosmos. The system postulates ten spheres, or sephiroth, that make up the energetic circuit of creation—beginning with Godhead and terminating in manifest reality. This map demonstrates how reality comes into being, starting from the void, progressing through the mind of God, into causal blueprints carried out by angels, through the astral world of dreams and emotions, and then into the physical world. Likewise, it shows how everything that has already been manifested inter-links and connects into a cohesive whole. As a more sophisticated version of the Great Chain of Being, it shows how to reascend the ladder back to God and, for the mens adeptus, suggests how to participate in the patterning and continual manifestation of the universe.

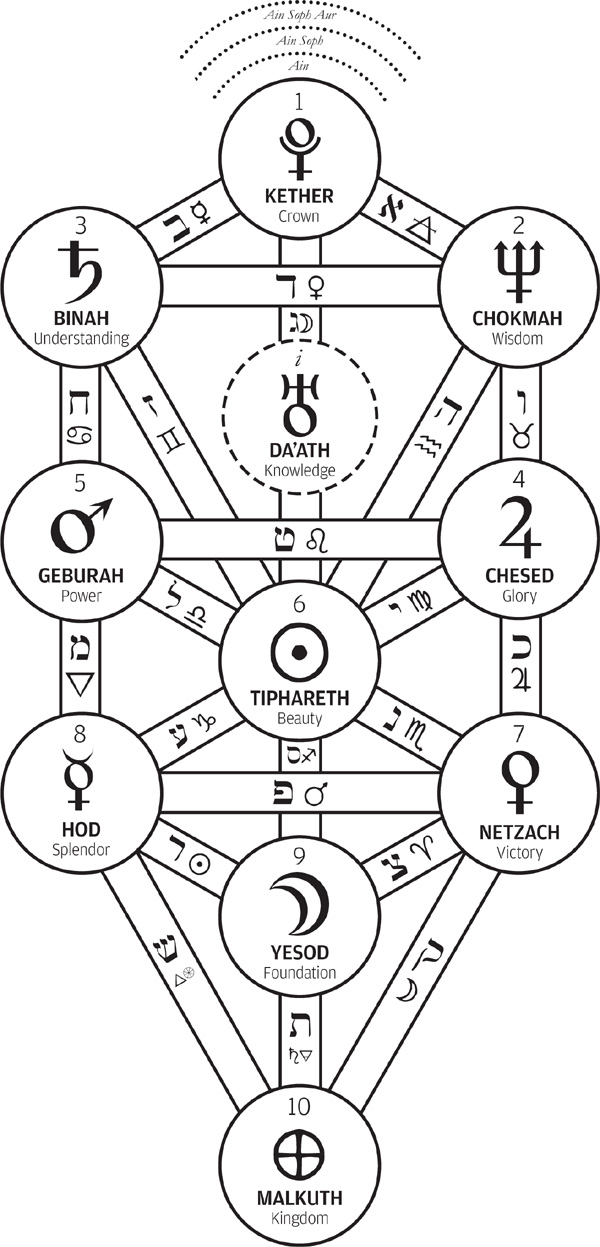

Brief summations of the ten spheres, in modern terms, are as follows:

- Kether, Crown. Godhead. The spark of Creation, or Big Bang.

- Chokmah, Wisdom. Positive/Masculine. The stars and zodiac.

- Binah, Understanding. Negative/Feminine. Saturn.

- Chesed, Glory. Structure. Jupiter.

- Geburah, Power. Separation. Mars.

- Tiphareth, Beauty. Divinity as manifest in humanity. The sun.

- Netzach, Victory. Emotion. Venus.

- Hod, Splendor. Intellect. Mercury.

- Yesod, Foundation. Sex, dreams, life energy, the “astral plane.” The moon.

- Malkuth, Kingdom. The physical world. Earth.

To these are added zero, Ain Soph, the void, as well as a theoretical sphere, Da’ath, Knowledge, which corresponds to the separation between spheres one through three and seven through ten, the “Abyss” between unmanifest and manifest existence, noumenon and phenomenon. The Abyss also represents the utmost limit of the rational mind, beyond which it cannot pass.

The sephiroth are not a literal map of reality. Rather, they are a map of mankind’s capacity for creating meaning, which shows that the entirety of human thought can be condensed into the numbers zero through ten. These ten spheres are connected by twenty-two paths, each of which blends the two spheres it connects, and they are assigned to the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet—meaning that the structure of the Qabalah is an outgrowth of the Hebrew language itself.2 This forms a pattern referred to as the “Tree of Life,” and raises its total number of spheres and paths to thirty-two. In addition to the Hebrew alphabet, these spheres and paths were assigned to combinations of the four classical elements, seven classical planets, and twelve zodiacal signs (this point, in particular, is of key importance to the later angelic conversations).

Fig. 5.1. The Tree of Life. Image courtesy of the author.

To these paths, it was thought, could be attributed the totality of human knowledge, as well as the totality of the aspects of the physical universe—a Renaissance prototype of a neural net. As such, the Qabalah forms a cohesive map of the human mind, and as mankind was thought to be made in God’s image, therefore infers a map of the mind of God. By the analogical thinking of operative magic, in which like is connected to like, this map could also suggest pathways by which an individual could influence anything in the universe.

Much as the Great Chain of Being does, this version of the Qabalah suggests that most humans are following a downward trend of manifestation, proceeding from God into the gross materiality of the physical world. An intrepid initiate, however, could reverse this course, reascending Jacob’s Ladder back to their source and thereby restoring their original divine nature. The Hermetic Qabalah thus formed the ground plan for undertaking this inner adventure, and completing the Great Work.

In addition to the map of the Tree of Life, the Qabalah incorporates the processes of gematria, or adding up the numerical values associated with the Hebrew alphabet to discover hidden meanings and analogies in scripture. For the working Qabalist, this process is extended beyond the written word and into the whole of nature.

Qabalah has a tendency to terrify with its complexity, but is simple in practice—in fact, people in Western societies have been immersed in it their entire lives, as its association chains are hardwired into Western civilization. As an example, consider the sphere Netzach, symbolizing love, to which correspond the planet Venus, roses, copper, the goddess Aphrodite, the virtue of unselfishness, and so on. This cluster of associations should make perfect sense, for Westerners, as all relating to each other and to the concept of love. This is Qabalah: understanding and categorizing nature as a language of correspondences.

Now, to extend this further and begin to think like an operative magician, consider the “magical operation” of using these Qabalistic correspondences to create a talisman to win or reinforce the love of a sweetheart. Give her seven roses (not too few, not too many), a copper locket, and a card with a poem written to her as if she were the goddess Aphrodite, and see what “magical” effect this has. Of course, you may say that there’s no value in such objects and ritual gestures, and it’s the thought that counts, but see how far that gets you.

The analogical and associative meaning-building of the Qabalah can seem daunting and even opaque to noninitiates, like somebody looking into a manual on advanced computer programming or differential calculus for the first time. Yet as with these arts, the processes of Qabalah were created in order to do complex things more easily. Once the initial learning curve is passed, Qabalah allows for complex association chains that decrease the overall mental operations needed to work out any given problem. A student of Qabalah will seek to relate everything in their life to the Tree, until the whole of existence changes from a chaos of noise and information into a perfectly organized filing cabinet.3 From here, the mental silence of meditation becomes easier, and the mind becomes still enough to receive wisdom from that silence.

This method of jnana yoga is not for everybody—spiritual adherents with more physical or emotional temperaments will gravitate toward hatha yoga (physical postures) or bhakti yoga and prayer—but for compulsive intellectuals, it can be a blessing, as it is meant to overload the rational mind with divine semiotics until the discursive mind finally breaks and lets go, allowing merciful moments of transcendence from the reasoning faculty or ruach. One soon sees the connections between literally everything in nature—every number, word, color, godform, personal interaction, mode of consciousness, and even thought collapses into a shining whole, revealing that the totality of the universe is connected, and is itself the mind of God in the process of manifesting itself. It is from this process that we get the stepped-down occult artifacts of numerology, tarot, color symbolism, and all the rest—yet what were analogical tools in the enlightenment machine of initiates become gaudy fortune-telling devices in the superstitious hands of the unawakened.

The Kabbalah—which was brought to Europe by Sephardic Jews—was believed to have been received from God; the Tree of Life is first seen in the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2:9, side by side with the forbidden Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.*5 The structure of the Hebrew alphabet itself is described in rabbinical literature—primarily the Sefer Yetzirah—as depicting the process by which God manifested the world in Genesis 1. Therefore, the entirety of the Old Testament was saturated with coded Kabbalistic meaning, all the way down to each individual letter.

The Tree itself later appears in Proverbs 3, in which it is explained that by keeping God’s commandments one may reattain to the supernal sephiroth: “Happy is the man that findeth wisdom, and the man that getteth understanding. . . . Her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace. She is a Tree of Life to them that lay hold upon her: and happy is every one that retaineth her. The Lord by wisdom hath founded the earth; by understanding hath he established the heavens. By his knowledge the depths are broken up, and the clouds drop down the dew.”4 The reference is to Chokmah or Wisdom, Binah or Understanding, and Da’ath or Knowledge; the feminine presence is likely the Sophia, Wisdom, personifying Chokmah.

The Tree of Life returns triumphantly in Revelation 22, where it stands in the center of the New Jerusalem after the final victory over the Dragon, just as it stood in the Garden of Eden, for as Christ is the Alpha and Omega, the Tree opens and closes the Bible: “And he showed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the Throne of God and of the Lamb. In the midst of the street of it, and on either side of the river, was there the Tree of Life, which bare twelve manner of fruits, and yielded her fruit every month: and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.”5 Access to the Tree through the gates of the New Jerusalem (possibly a reference to the fifty gates of Binah or even the thirty Aethyrs) is the reward of those who have kept God’s commandments and have not fallen to the evil power, for “without are dogs, and sorcerers, and whoremongers, and murderers, and idolaters, and whosoever loveth and maketh a lie.”6

Practically, this meant that not only was Qabalah the key to understanding scripture, but also to understanding the angels and spirits contacted through operative magic. For instance, a spirit that appeared in a vision wearing a red cloak and carrying an iron sphere would be assumed to be an aspect of Mars and the sphere of Geburah. In this way, spirits could communicate complex meaning by their appearance, actions, words, and gestures. Understanding this is critical to making sense of Dee’s angelic conversations, as well as Crowley’s later scrying of the thirty Aethyrs.

Following the work begun by Agrippa in synthesizing the Qabalah with operative magic, nineteenth-century occultists like Eliphas Levi, MacGregor Mathers, and the initiates of the Golden Dawn would use the Qabalah as a way of drawing together the entire doctrine of magic, including the gods, goddesses, and spirits of all of the world’s religious traditions, as well as astrology, tarot, I Ching, the magical languages of the grimoires, and every other piece of lore they had inherited or invented, culminating with Dee and Kelly’s angelic magic, fitting it all together as a single working model that an intrepid magician could use as a road map to enlightenment. Following the SRIA (Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia) and earlier orders, the Golden Dawn would also use the Qabalah’s ten spheres as a Masonic degree structure, suggesting that these spheres were not only ways of classifying the universe, but also represented states of consciousness attainable by human initiates.

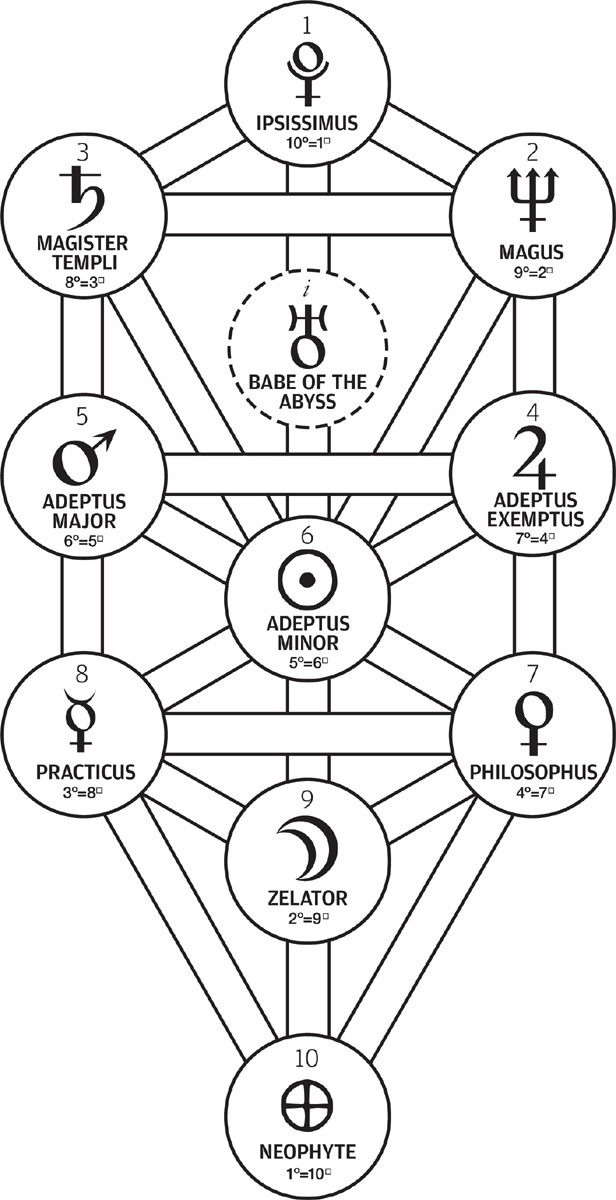

This degree structure would go through several iterations as it passed through the Masonic and Rosicrucian orders that postdated Dee. The version finalized in Crowley’s A∴A∴ is as follows:

0°=0□ Probationer. Outwith the Tree.

1°=10□ Neophyte. Malkuth.

2°=9□ Zelator. Yesod.

3°=8□ Practicus. Hod.

4°=7□ Philosophus. Netzach.

(Dominus Liminus. Veil of Paroketh.)

5°=6□ Adeptus Minor. Tiphareth.

6°=5□ Adeptus Major. Geburah.

7°=4□ Adeptus Exemptus. Chesed.

(Babe of the Abyss. Veil of the Abyss.)

8°=3□ Magister Templi. Binah.

9°=2□ Magus. Chokmah.

10°=1□ Ipsissimus. Kether.

Grades of this style were usually conferred in Masonic temple–style initiations, as in the SRIA and Golden Dawn, initiating the candidate into the mysteries of each sephira and allowing them to climb the Tree of Life, thus formalizing the quest of the Renaissance adepts to reascend the Great Chain of Being, return to God, and become mens adeptus.

While this mapping of the Qabalah to Masonic-style grades does not directly apply to Dee’s work, it becomes critically important to assessing the work of the magicians who applied themselves to Dee’s magic after his death, as the majority of them worked within Qabalistic, Masonic structures and interpreted their experience of angelic magic through that filter. In particular, Aleister Crowley conceptualized his entire experience of Dee’s thirty Aethyrs as not only spanning and elaborating upon the structure of the Qabalah, but as an initiation into the grade of 8°=3□ Magister Templi and the sphere Binah, following the earlier rabbinical tradition of initiation through the fifty gates of Binah.

While this structure stems wholly from the Golden Dawn, and not from Dee’s original work, the later work of Mathers, Crowley, and others in mapping Dee’s magic to the Qabalah can help elucidate the original material in retrospect—particularly when remembering that much of the Golden Dawn is based on Agrippa, whose Three Books were Dee’s primary sourcebook for magic. For instance, many of the utterances and appearances of Dee’s angels make sense when analyzed using the correspondences from Agrippa (or the Golden Dawn). Even back-testing Crowley’s assumption that the angelic material pertained to initiation into Binah seems to bear this out.

All of this will be discussed in more detail in book III; for now, the key takeaway is that Dee heavily studied Qabalah, beginning with his association with Guillaume Postel, and that it became key to his thinking from the early 1560s onward, as exemplified by his Monas hieroglyphica. As a result, Qabalah is central to understanding the angelic conversations, and was teased out and emphasized by the later magicians who experimented with Dee’s work.

Fig. 5.2. A∴A∴ Grades on the Tree of Life. Image courtesy of the author.

Dee quickly incorporated his new study of Qabalah and of the Hebrew language with his prior occult learning. Beginning students of Qabalah and gematria spend immense amounts of time studying Hebrew, memorizing correspondences between the Hebrew letters and various facets of the natural and supernatural worlds, and then projecting those correspondences outward into reality. Eventually, everything takes on Qabalistic significance, and everything is seen to be interconnected. But the entire methodology of Qabalah, gematria, and numerology is arguably only a synthetic method for inducing a state of consciousness in which the boundary between self and other dissolves—a set of training wheels that may be discarded once it does its job.

Dee, likely understanding this through his own study, pushed much further, and wrote not of the Hebrew Kabbalah but of the “Real Cabala,” the true language of God that Hebrew only approximated. He would later come to call this the Cabala “of that which is” in his Monas hieroglyphica, as opposed to the Kabbalah of “that which is said,” namely Hebrew. For Dee, the Real Cabala would supersede the exoteric Hebrew Kabbalah, and in the process unlock the inner, sacred, initiated meaning of the classical sciences. Arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy, optics, statics, pleno, and vacuo (these last relating to Aristotelian physics) would be superseded by magic, esoteric medicine, scrying, alchemy, and, finally, adeptship itself.7

This was the quest for the primal, pre-Fall language. The recovery of such a language held out the additional promise of a reconciliation between the divided religions—not only Catholicism and Protestantism, but Judaism and Islam as well.8

Dee’s Qabalistic mentor Guillaume Postel had already hinted at such a primal language, suggesting that the prophets Enoch and Abraham probably spoke a language closer to Adam’s original tongue than the Hebrew then known, and had investigated the Qabalah of Chaldean, Aramaic, and even Syriac, which he (like Agrippa) considered the holy language of Christ, laden with profound meaning.9 Johann Reuchlin wrote that the angelic language had been simple and pure, and spoken between God, angels, and men face-to-face, casually, without need for interpretation.10 St. Augustine—and following him, Aquinas, Luther, Ficino, Conrad Gessner, and Paracelsus—believed that Hebrew itself was the original language, and the sole survivor of the fall of the Tower of Babel; Augustine also believed that there was an “inner word,” reflecting the logos that resonated within the soul of man, beyond all verbal language.11 Agrippa argued that the Adamic tongue was never spoken at all, but passed between God and individuals telepathically, through the medium of the imagination. This divine language was of particular importance to operative magicians, as it would be the key to communicating with the angels. Pico della Mirandola and Reuchlin thought that such divine words would also contain miracle-making faculties in their own right.12

5.3. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa.

As Dee’s world model was growing in sophistication, so was his sense of identity. Following Postel, he was beginning to see himself as a “Citizen and Member of the whole and only one Mystical City Universal,” a “Cosmopolites,” a citizen holding allegiance to no country but God’s.13 This sentiment, which dates to Diogenes of Sinope in the fifth century BC, has become progressively more common in the modern world as globalization erases national borders, a project that Dee, his peers, and the Rosicrucian and Freemasonic movements he inspired might be seen to have had a guiding spiritual influence on.

Such a seemingly pious sentiment could be interpreted in many ways. One might be that Dee, finding more in common with his European intellectual and occultist contacts than his countrymen, was beginning to consider himself a member of the elite, those who saw beyond national and territorial politics, who were concerned with the eternal world of ideas and of the betterment of the human race. The circle of adepts that Dee was now finding himself within—bound by common ideas and drives, if not literally organized—would be responsible for much of the advance of the Western world in the coming centuries, from the birth of science to the Freemasonic-inspired political revolutions that swept Europe and led to the birth of America and the Napoleonic age. Another is that this may have been a tell that Dee was now an initiate not of a metaphorical circle of similar thinkers but of a literal secret society, perhaps a forerunner of the Rosicrucians to come.

The statement certainly points to where Dee’s religious loyalties truly lay—beyond either Catholic or Protestant. Though Dee had studied with Catholics, been ordained a Catholic priest, and had professed loyalty to the Catholics under Mary, his lack of celibacy and interest in magic made him more than suspect. A secret 1568 report submitted to Francis Borgia, Jesuit superior general, called Dee “a married priest, given to magic and uncanny arts,” and a pernicious influence that English Catholics would do well to keep away from.14 Yet Dee remained in awe of Catholic ritual even late in life, considering the Eucharist of primary importance to spiritual development.15 Under Elizabeth, however, he had switched loyalties to the evangelical cause. The political question of which side of Christendom he allied himself with was secondary to saving his own skin and staying alive to pursue the Hermetic quest for the prisca theologia, which would make such religious factionalism irrelevant.

These were the ideals—a new “Hermetic religion of love,”16 as Dee biographer Peter French called it in the early 1970s—that the young Dee was immersed in. This was not a game: the ideals of Dee’s Continental elders could get an unwary philosopher killed, and Dee had already been tortured for “calculating and conjuring.”

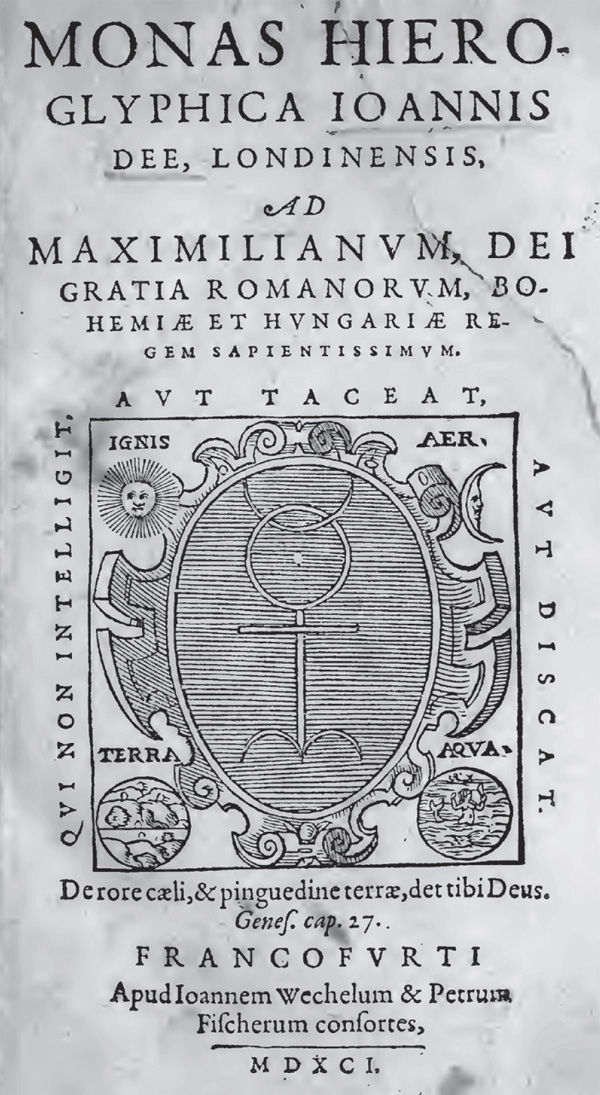

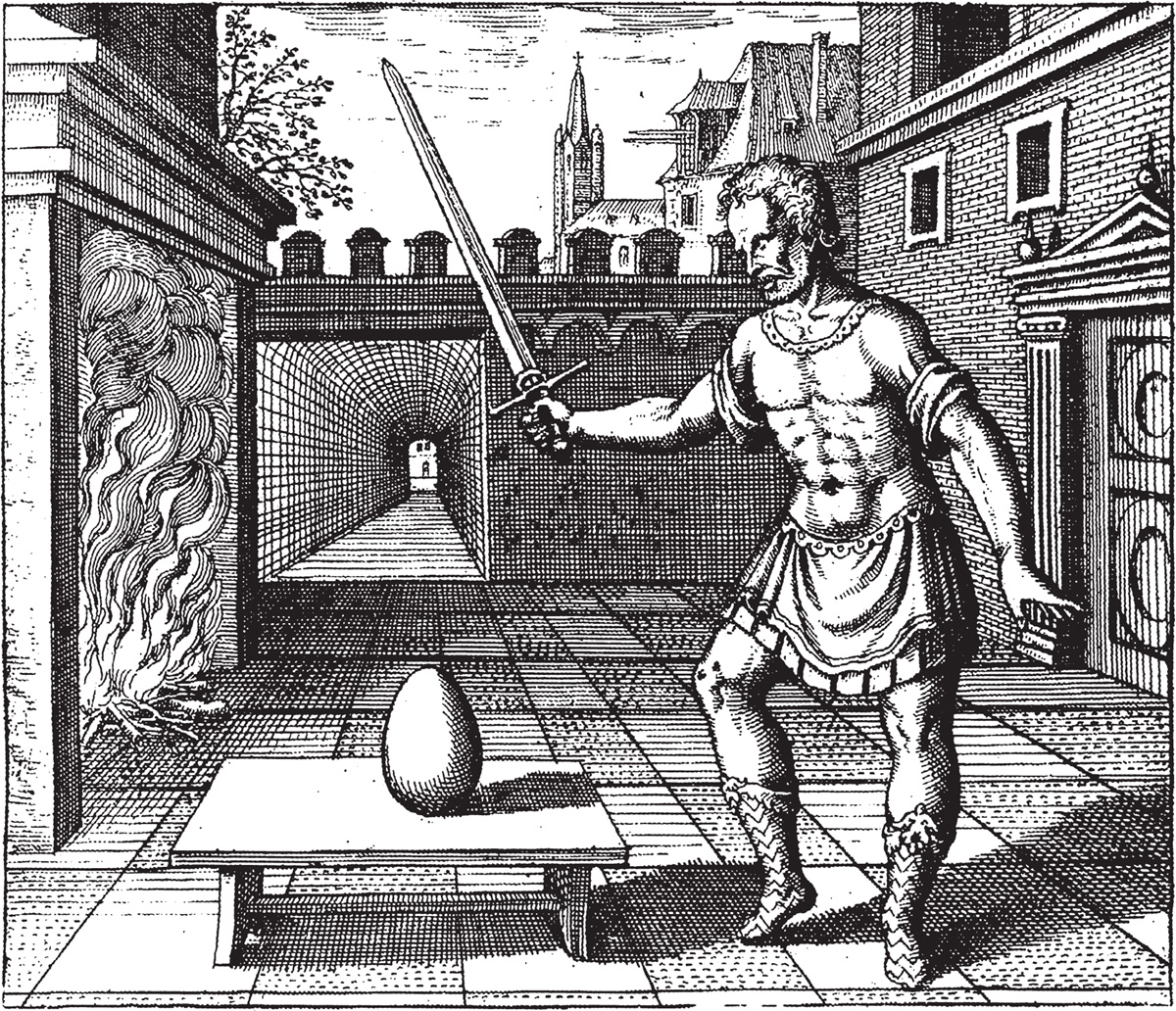

His head full of dangerous new ideas, Dee returned to Antwerp to compose the crowning work of his early life. Synthesizing the totality of his previous learning, and freshly inspired by the Qabalah, Dee produced the Monas hieroglyphica, a short work that purports to unveil the secrets of the Real Cabala and of the universe itself in one symbol and twenty-four theorems—twenty-four being the number of Elders that surround the Throne of God in Revelation 4:4.

Fig. 5.4. Title page of John Dee, Monas hieroglyphica, 1564.

Like the Propaedeumata, the Monas was an attempt at Continental patronage: it was addressed to Maximilian II, soon to become the Holy Roman emperor, who became a great supporter of science and the arts during his reign, as well as an enthusiast of hieroglyphics.17 Bitterly remembering the opportunities for royal patronage he had turned down before returning to England, Dee now struggled to reclaim what he had so flippantly discarded.

To help in his self-promotion, Dee now cast himself as an adept, rather than just a math professor, suggesting that he possessed secret occult knowledge that could prove a political asset for a monarch who sheltered him. This was not a hollow promise—the Monas does point the way to philosophical adeptship, and outlines the Real Cabala, which Dee thought could not only unlock the works of the ancients, but also spark new scientific advances.18

The Monas is a profoundly advanced and yet elegant Qabalistic text, though little trace of Hebrew or even the Tree of Life remains visible on its surface. Instead, Dee condenses the entirety of nature into a single symbol, the Hieroglyphic Monad itself. Dee’s Monad had appeared on the cover of the Propaedeumata aphoristica six years earlier; the Monas now revealed the meanings of the symbol that he had been carefully working out during his deep study of Qabalah in the intervening years.

The Monad, which resembles the alchemical sign for Mercury (an analogue of Hermes, suggesting the Hermetic roots of the text), is assembled from the symbols for the sun, moon, the cross of the elements, and the sigil of Aries, which also represents the twenty-four hours of the day and therefore the sun’s motion throughout it, as well as the rest of the zodiac and the Elders of Revelation. When the Monad is manipulated and rotated, it reveals the symbols of the remaining classical planets—Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Thus, the Monad contains the entirety of the Qabalah, with its four elements, seven planets, and twelve zodiacal signs displayed in a single sigil, rather than the complex map of the Tree of Life. Therefore it contained the entirety of nature, and was the Key of the Mysteries and Dee’s effort to establish a Real Cabala, one based on geometry and direct observation of the world.

If this symbol showed the unity of all things, Dee suggested, then by its further study and manipulation, anything in the universe could be deduced. The Latin text of the Monas hieroglyphica was made up of twenty-four theorems on the sigil, in which Dee breathlessly extrapolates meaning upon meaning from it, applying his masterful grasp of geometry, astronomy, Qabalah, Pythagorean number theory, alchemy, scripture, Greek, Latin, and Hebrew. Throughout the book, Dee continually emphasizes that what he reveals are only some of the mysteries that can be extrapolated from the Monad, and that the symbol may contain boundless further treasures and avenues of inquiry. Ultimately, Dee thought, the Monad would collapse all of the mundane and magical arts into one, uniting all knowledge (including the forbidden) into a greater whole. Yet despite his enthusiasm, Dee is simultaneously guarded, couching much of the book in alchemical metaphors and twilight language. As with some of his theories in the Propaedeumata, Dee believed that revealing the mysteries of the Monas to the profane would lead to their misuse and therefore to disaster. Unfortunately, this use of twilight language ensured that its intended audience also found it inscrutable, at a time when Dee hoped to secure patronage.

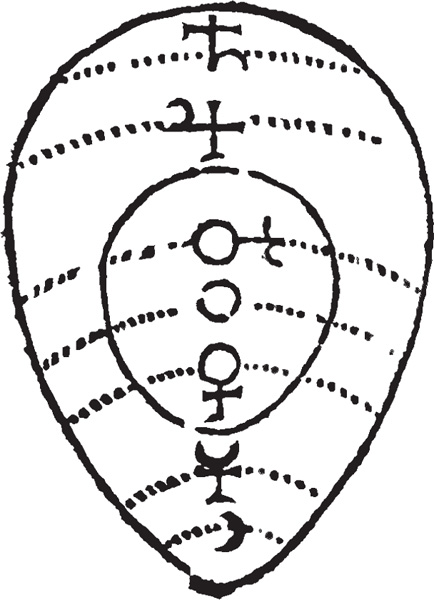

Fig. 5.5. The Hieroglypic Monad. From Monas hieroglyphica.

Constructed of coded information hidden layers upon layers deep, the Monas requires an intuitive grasp of Qabalah, astrology, geometry, and alchemy—intuitive being the key word, as its meaning does not unfold solely in a rational manner but also through meditative contemplation. Dee does not do any hand-holding in the text, assuming that his readers will be on mental par with him, stating, “Here the vulgar eye will see nothing but Obscurity and will despair considerably.”19 Furthermore, he counsels that those unable to understand it should keep quiet rather than pretend to knowledge they have not earned, stating, “Who does not understand should either learn or be silent.”20 This cageyness on Dee’s part was warranted, for in addition to being the proposed key to the universe and the solution to all problems then facing humanity, the text almost certainly contained encoded political material.

The Monas further includes information on the application of its theorems to alchemy. This was sure to get the attention of potential patrons, as the production of gold was of primary interest of European monarchs. The process of alchemical transformation described in the Monas is the purification of the soul and its translation from sublunary corruption to the supercelestial world;21 however, it must also have been applicable to more mundane efforts of transforming metals, as in the 1580s Elizabeth would establish secret alchemical laboratories at Hampton Court Palace, where she would draw upon the theories in the book in an attempt at the industrial-scale production of gold.22

Dee begins the Monas with a circle, a line, and a point. These are the primary forces of manifestation—corresponding, though this is not stated, to Kether, Chokmah, and Binah. As a point implies a line, so a line implies a circle, because a line rotated around a point creates a circle, and it is likewise impossible to draw a perfect circle without a point or line. As these lineal figures further develop in complexity, they leave the domain of the conceptual and enter the world of manifestation, glyphing the process by which the universe creates. Through becoming absorbed in this process, the reader may transcend the limits of their own rational mind and enter into communion with universal truths.23

A circle around a point creates the alchemical sign for the sun. Halved, a circle forms the alchemical sign for the moon. Conjoined, these represent the alchemical marriage of sun and moon that is mentioned in The Emerald Tablet (“The Sun is its father, the moon its mother,” in Isaac Newton’s translation),24 in the Hindu tantras (“When a yogi unites that which is above and that which is below, he unites Sun and Moon, realizes Om and is one with the Hamsa,” from the Niruttara Tantra),25 and in Crowley’s The Book of the Law (“For he is ever a sun, and she a moon”).26

This marriage creates the cross of the elements, which can be read as either ternary (two lines and one central point, equaling three) or quaternary (four right angles). Together, this implies a septenary (sevenfold) structure. This cross is placed upon the astrological sigil of Aries, representing fire as it is part of the fiery triplicity, and also representing the movement of the sun across the equator over the course of the twenty-four-hour day.

The math outlined here by Dee would form the underlying structure of the temple furniture delivered by the angels in the much later angelic conversations. The angel Il would tell Dee that the angelic Holy Table worked on a ternary and quaternary structure,27 on top of which was placed the septenary Sigillum Dei Aemeth and Ensigns of Creation; likewise, seven times seven yielded the forty-nine good angels of the Tabula Bonorum and the forty-nine angelic calls. When multiplied, three and four yield the twelvefold structure of the angelic flags and the twelve tribes of Israel. Twelve plus twelve yields the twenty-four seniors of the Watchtowers, while twelve times twelve (to the magnitude of a thousand, which simply means “a lot” in biblical math) yields the 144,000 to be saved in Revelation. The Watchtowers themselves would be quaternary, elaborating the four elements.

Dee next shows how, when rotated or taken in segments, the Monad produces the astrological symbols for Saturn, Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, and Venus—which combine with the sun and moon to make up the seven classical planets, which also formed the later structure of the Sigillum Dei, the Ensigns, and the Tabula Bonorum. Next taking the central cross, Dee shows how it can be broken down into the Roman numerals L, V, and X, from which a decadal structure can be extrapolated.*6

Importantly, the central cross, for Dee, can represent one X, four Vs (four times five equals twenty-five), or four Ls (four times fifty equals two hundred); he relates this to L or El, a Cabalistic name of God and of Jupiter. El is also the suffix appended to the names of angels in Hebrew, denoting their species (Raphael, Gabriel, Michael, Uriel, and so on). L or El is a centrally important repeating symbol within operative magic—seen previously in grimoires like Liber iuratus, it would also form the central character of the Holy Table of Practice, and therefore the center of the entire angelic conception of the universe.*7

This elucidates the structure of the Monad and thus the cosmos: If a point implies a line, and a line implies a circle, and this can be doubled to form a cross in a circle, ten, then this, for Dee, implies that all of manifestation can be drawn from a single point. In the thinking of the Qabalists, a single point represents the spark of Creation, Kether, while the number ten, Malkuth, the tetractys, then not only represents but is the universe itself.28 If you have ten, you have everything.

Dee further develops the Monad by arranging the seven planets in progressive orbits in an egg structure, and couching the structure within alchemical allegory.†8 Dee suggests that the three parts of the structure—the sun and moon, the cross, and the equinoctial sign of Aries—form a dramatic beginning, middle, and end, analogous to the birth, death, and resurrection of Christ and the alchemical perfection of Adam, among many other formulae.*9 Dee concludes by pointing out that the twenty-four hours represented by the sign Aries are also the twenty-four elders that ring around the Throne of God in Revelation; implied is that the Monad signifies not only all Creation but also the narrative arc of the Bible—from the point of Creation, to the Cross, to Revelation. These elders or “seniors” would appear as tangible spirits to Kelly in the vision of the golden talisman, and thereafter be incorporated into the angelic Watchtowers.

Fig. 5.7. The seven planets extrapolated from the Monad and arranged into an egg shape. From Monas hieroglyphica.

Fig. 5.8. The orbits of the planets from the Monad. From Monas hieroglyphica.

Scholars have proposed a multitude of theories about the Monas. It is generally accepted that the book is an alchemical and Qabalistic document, the fruit of Dee’s thinking on the Qabalah “of that which is.” Francis Yates proposed that the Monad was believed by Dee to be the occult, scientific, mathematical key to reascending the Great Chain,29 while others suggested that the book was a proposal for a new world order and world religion—a Hermetic order that would pave the way for global salvation, although this latter theory lacks sufficient evidence.30 (Dee’s actual plans for a global religion would come later, during the angelic conversations.)

Fig. 5.9. Alchemical emblem. From Michael Maier, Atalanta fugiens, 1617.

Dee was right to seek for foreign patronage by promoting his new work: though Dee sent a copy of the Monas home from the Continent, it was not well-received in England, necessitating that Elizabeth defend Dee’s reputation against “such Universitie-Graduates of high degree, and other gentlemen, who therefore dispraised it, because they understood it not,” even though she had not yet read it.31 Unfortunately, the book found no better reception with Maximilian, and Dee returned to England with his dreams of patronage dashed once again.