6

Hammer of the Witches

Dee faced a harsh comedown upon reentry to England. While on the Continent, he had been seen as the natural philosopher and adept he was, free to pursue his flights of intellectual fancy, chasing Hermetic manuscripts and daydreaming of a royalty-backed occult revival. But back home, he was just a demonic conjuror, considered no better than a common criminal. By July 1564, his reputation as a sorcerer and Catholic had grown, as his enemies had taken his absence as an opportunity to attack freely.

Elizabeth’s court was very different from Mary’s. While Mary had been a fanatic Catholic, Elizabeth was tolerant, even fascinated with the occult. Elizabeth was a genius, Dee’s equal or better—her scholastic efforts even as a child are extraordinary. Her command of languages was masterful; her tutor Roger Ascham once remarked that Elizabeth read more Greek in a day than clergymen read Latin in a week.1 Artists and poets portrayed her either as a virgin or a goddess—never as a mortal woman.2 Beyond this, she practiced operative magic in her own way—an example being the “royal touch,” a traditional ritual of the English monarchy, in which she would apparently heal epilepsy or tuberculosis by placing her hand on the neck of the afflicted. Elizabeth is recorded as being exceptionally effective at this faith-healing practice—though openly claiming one had not been so cured would have been an unwise move.3

Once enthroned, Elizabeth’s interest in science and alchemy became publicly known, with alchemists throughout Europe seeking her patronage; she was considered to be more learned on the topic than most professors, and fashion soon dictated her association with the alchemical emblems of the pelican and phoenix, representing stages in the work of creating the philosopher’s stone. The way to Elizabeth’s heart was alchemy—and so it is little surprise that Dee had many rivals for her attention. Beyond creating an air of jealousy, this situation now proved perilous for Dee. Court politics were vicious and backbiting in alchemy as in all else, and the stakes were high—winning Elizabeth’s favor meant winning riches, fame, and security, while falling from her favor could mean death.4

To distinguish himself as superior to his rivals for Elizabeth’s patronage, Dee presented her with the Monas. She received it with fascination, telling Dee that she would become his “scholar” if he revealed the secrets of the book to her.5 Dee soon became closer with Elizabeth, but not close enough to secure a stable position.

In 1563, Elizabeth had passed the Act against Conjurations, Enchantments, and Witchcrafts, a new legislation against the occult that nevertheless lightened the sentence for sorcery, which was now only punishable by imprisonment. The previous standard of the death penalty without benefit of clergy was now reserved only for those who killed with magic. While Dee had been away, Elizabeth’s court had been warring with Catholic conspirators and magicians who were indeed this unscrupulous. The arch-conspirator John Prestall was once again involved, and was accused of conjuring evil spirits to gain information on how best to commit treason, as well as telling other conspirators that he had predicted Elizabeth would die in 1563.6 Cecil had the subversives publicly tried in Westminster Hall, though they were not executed. Prestall was thrown in the Tower of London—seeking to strike back at Cecil but fearing retaliation, he instead sought to indirectly hurt Cecil by going after Dee.

As ammunition against Dee, Prestall used the 1563 first edition of John Foxe’s Actes and Monumentes, which contained a record of Dee’s 1555 testimony during Bishop Bonner’s examination of the Protestant martyr John Philpot. During his testimony, Dee asked the heretic Philpot if he would concede that the pope should be the supreme head of the Church—if Dee could prove that Christ built the Church on Peter, and not Cyprian. Dee was chided by the older man, who told him from the stand that despite Dee’s academic learning he was “too young in divinity to teach me the matters of my faith.”7 Included in the book is a letter that had surfaced between Philpot and Bartlet Green, another Protestant martyr who had been in the care of “Dr. Dee the great conjurer”8 while held in Bishop Bonner’s house.9 The letter was enough to link Dee with both sorcery and, because of his close proximity to Bonner, the Catholic cause.

Prestall had initiated a storm of gossip among the public. In addition to the passage referring to Dee as a “great conjurer,” a number of counterfeit passages were inserted by Dee’s enemies embellishing the charges against him; on top of this, documents claiming Dee consorted with demons were broadly circulated by agitators. The primary counterfeiter was later identified as Vincent Murphyn, Prestall’s brother-in-law, another cunning man who trafficked in using nails and hair to effect harmful sympathetic magic, evoking spirits, and forging letters to cozy up to powerful friends. If Prestall and Murphyn could not match Dee in genius, they could trump him in the propaganda war by using underhanded occult thug tactics that Dee, a naïve and idealistic scholar, would have been blindsided by. This was a very different kind of magic—the conjuration of the worst demon of all, the mob. Prestall and Murphyn’s logic was clear: if Elizabeth was going to go after Catholic conjurors, they would turn public anger against the conjuror in Elizabeth’s own employ. In one move, this would take out an occult rival, enact indirect revenge against their persecutor Cecil, and, most importantly, shift attention away from them and toward the perceived hypocrisy of the government’s stance against witchcraft. Prestall and Murphyn were not to be trifled with in street-level magic, yet in the process of their revenge they were damaging a brilliant scholar and harming the strength of their country—not that the politically amoral Prestall would have cared.10

Dee would never recover from the damage done to his reputation during this period. It was this furor, and his earlier imprisonment for calculating—not the prior scandal caused by his winged beetle or the disgrace his father had come to—that would truly tarnish his image and permanently mark him as a figure of suspicion. Not only was Dee a conjuror, he was now a “great conjurer”—a reputation that Dee still bears more than four centuries later, though what was a burden at the time has preserved Dee’s memory in the long run, while less colorful contemporaries have been forgotten. The blow must have been crushing. Dee had worked long and hard for pure knowledge, and to advance the spiritual status of humanity—and this was his reward.

Faced with such trauma, he took the natural next step: he got married. Katheryn Constable, Dee’s bride, was not of equal stature to him—she was a City matron, who had been married to a general trader and associate of Dee’s father, Roland. Dee was marrying below his station. In addition, marriage meant he was making a public statement that he was no longer celibate, not only scuttling any remaining hope he had of attaining a religious post, but putting his life at risk were Catholics to return to power. Dee, now thirty-eight, may have been giving up.11 His marriage was only to last ten years—Constable would be dead by 1575, without giving Dee children.

His career over for the time being, Dee settled with Constable at Long Leadenham, and divided his time between his wife and his mother at Mortlake. In the meantime, Prestall and Murphyn continued their efforts to bury the “grand conjurer,” while the occult war between Mary, Queen of Scots (also widely suspected of practicing witchcraft), and Elizabeth intensified.

It seems that Dee’s problem was not so much that he was a magician, but that his brand of magic was impractical. The claims of the Monas to reform all knowledge were impressive, but what was really needed was somebody who could enrich the government coffers by turning lead into gold, or who could at least silence the court’s enemies. And though Dee was brilliant, he couldn’t hack practical alchemy. Even Prestall and Murphyn, it seems, could deliver better; given Murphyn’s history of using forgeries to secure powerful friends, a large part of their campaign against Dee may have been aimed at removing a professional rival. But Elizabeth’s court shifted its favor to rival alchemists Thomas Charnock and Cornelius de Lannoy—ironically, the court had been inspired by the Monas that the production of gold might be practical, but they hired somebody else to follow through. De Lannoy promised the court that he could manufacture £33,000 of pure gold, diamonds, and precious stones a year, the equivalent of about £7.9 million (or $9.9 million) in 2017. Dee, in comparison, had only promised philosophical flights of fancy.12

Elizabeth’s court was broke, and easily fell for the hollow promises of the con man de Lannoy; the queen furnished him with the salary, rooming, and royal support that Dee had yearned for. Elizabeth, Cecil, and Dudley, all interested in alchemy, eagerly awaited his results, but they failed to manifest; it was next suspected that de Lannoy was using the royal support and furnishing of instruments to create gold for himself. Elizabeth was busy with her own alchemical experiments—with the aim of fighting her smallpox and ceasing her aging—and worked to check de Lannoy’s methods. De Lannoy was eventually arrested, placed in the Tower, and interrogated. Yet his failure to make good on his claims did not arouse skepticism of alchemy itself—only of de Lannoy’s approach. Not one to miss an opportunity, Prestall seized the moment to have himself released from the Tower, offering to provide what de Lannoy could not.13

Dee’s bitter response to this drama was to yet again begin looking for Continental patronage. He translated the Monas into German and again sent it to Maximilian II, now Holy Roman emperor, with a new introduction. The repackaged Monas was now meant to portray Dee as an alchemist; it included a critique of the sham alchemists of the day, intimating that they had no ability to read the writings of the ancients and had confused the symbols, debasing initiated philosophy into unintelligible witchcraft. Maximilian ignored the book yet again. Dee next revised the Propaedeumata to include now-fashionable alchemical ideas from the Monas, with intimations that Dee might know how to produce the philosopher’s stone and extend human life, and presented it to Cecil. Elizabeth read the book, but was so disheartened after the de Lannoy scandal that she explained she had no interest in risking more money on alchemy. Yet as a result, Dee again came to Elizabeth’s awareness, and in February 1568 they are recorded as discussing alchemy at Westminster.14

With Mary, Queen of Scots, having escaped to England in 1568, Elizabeth had to contend with increased attacks from Catholic insurrectionaries—including dozens of publicized prophecies of her death, and even more grief from Prestall, now hiding across the Scottish border from a furious Cecil, who was contemplating a raid to capture him. Cecil, however, shrank from the border—unlike the more hawkish Dudley, he was wisely hesitant to take any action that would leave England without an ally upon its own island, particularly with the wolves circling.15 Taking advantage of Cecil’s political position, Prestall ensconced himself safely in Scotland, where he plotted to magically assassinate both Cecil and Elizabeth, and to goad the Spanish into attacking England.16 Again seeking to deflect attention from Prestall, Murphyn continued his assaults on Dee, accusing him of Satanism.

Running parallel with the Catholic attacks, the new Puritans entered the propaganda war, with the Puritan Thomas Cartwright, a professor of theology at Cambridge, drawing sharp contrast between the structure of the Anglican Church and that of the early Christians. And if the Catholics were prone to sorcery, the Puritans were anything but.

“They took the doctrines of predestination, election, and damnation deeply to heart, and felt that hell could be escaped only by subordinating every aspect of life to religion and morality,” wrote historians Will and Ariel Durant. “As they read the Bible in the solemn Sundays of their homes, the figure of Christ almost disappeared against the background of the Old Testament’s jealous and vengeful Jehovah.”17

After Edmund Bonner died in prison in 1569, Dee’s connection to the much-hated bishop was dragged back into the light of public scorn, which did not help Dee’s reputation. Indeed, in the background of this sorceric free-for-all, Dee was beginning his own initial forays into operative magic, conducting a divination with an associate named W. Emery to uncover the exact birth date and time of the navigator John Davis (who later discovered the Falkland Islands).18 Meanwhile, the Earl of Pembroke had died, leaving Dee without a source of patronage.

Yet while Dee struggled not to be dragged under by the superstitions of the public, a new opportunity was arriving to help build a more educated future. In a move that would presage the scientific revolution, the explorer Humphrey Gilbert, half brother of Sir Walter Raleigh, was hoping to create an academy in London that would train the children of England’s nobility, who would one day inherit the country, in the art of alchemy; Gilbert hoped that Dee would become involved in the academy, and sought approval of his idea from Cecil, who was fascinated by alchemy. Gilbert also expected a hasty discovery of the philosopher’s stone and the secret of the conversion of lead to gold, at the time an object of obsession for much of England’s nobility. But as the academy would have needed £3,000 per annum to operate (roughly £736,000 or $923,000 in 2017 terms), the plan did not meet approval, again leaving Dee in the lurch in his quest for patronage.19 Gilbert was also a keen proponent of the profits that could be gained were England to discover the Northwest Passage, and hoped to found an English colony in the northwest of America from which to coordinate further exploration;20 his brother Adrian would later become a key player in Dee and Kelly’s angelic sessions.

Dee next sought work as an alchemical consultant for individuals and the government. Alchemical speculation was then big business, with courtiers racing to unlock the secret of the philosopher’s stone and planning to quickly scale the production of gold. With such large amounts of money and potential for patronage and royal favor being discussed, it is little wonder that inter-alchemist warfare, especially coming from Prestall and Murphyn, was so intense.

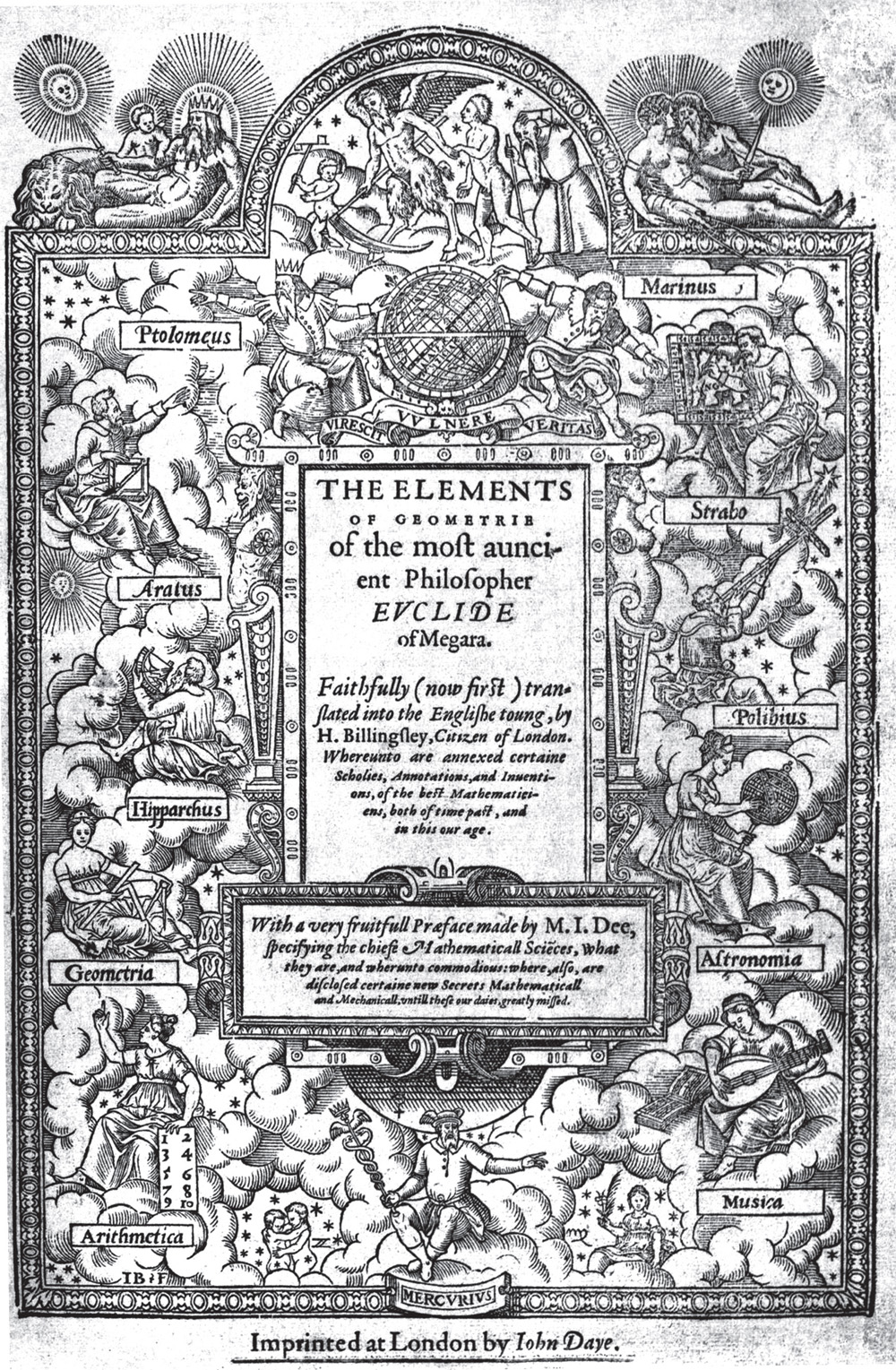

A new major work published during this time—Dee’s 1570 “Mathematicall Praeface” to Henry Billingsley’s massively successful and influential first English translation of Euclid’s Elements of Geometry—cemented his renown as a teacher of mathematics. The preface argued for the central importance of math (still viewed with suspicion by the public) to the sciences. The preface also elaborated many of Dee’s previous ideas from the Propaedeumata and Monas, suggesting that mathematics itself is a Hermetic pursuit, for it allows the mathematician to understand the thoughts of God and the method by which he had created and operates the universe. This was a vision of God as grand geometer and “Great Architect of the Universe,” as the Freemasons would later put it.

“All things (which from the very first original being of things, have been framed and made) do appear to be formed by the reason of numbers,” Dee explains in the “Praeface.” “For this was the principal example or pattern in the mind of the Creator. . . . The Heavens declare the glory of God, and the Firmament sheweth forth the works of his hands.”21

Dee suggested that not only had God created the universe using mathematics, but that he was continually refreshing reality by numbering it. Indeed, not only could he destroy things by removing the numbers that created them, but he could also slow down or stop his “continual numbering.” This itself was likely the causal reason for the decay of the world.22

Though giving a nod to mysticism, Dee would leave overt references to the Cabala out of his “Praeface,” a work intended for a much more hardheaded audience.23 Despite this, the “Praeface” contains many nods to more philosophically and spiritually minded readers, who will be receptive to Dee’s thoughts on using numbers to understand the mind of God, as well as purely materialistic readers who, like Dee’s father, would be interested in mathematics for reasons of business and profit.24

Beyond mathematics, Dee would recommend the full range of natural sciences, including the occult sciences of thaumaturgy and Dee’s own archemastery, not yet excised from the scientific canon.25 Archemastery itself was touted by Dee as the supreme science, fulfilling all other branches of learning, which proceeds through experiment and can lead to revelatory experiences. As Dee put it, again drawing on Roger Bacon, “Because it proceedeth by experiences, and searches forth the causes of conclusions, by experiences: and also putteth the conclusions themselves, in experience, it is named of some, Scientia Experimentalis. The experimental science.”26

As in the Propaedeumata and Monas, the implication was that by understanding God’s ways in the world, one could work with or even guide the forces of creation. Since man stands between God and the Creation, and is made in God’s image, he is suited to work with God as an intermediary, and mathematics is the ideal science for doing so,27 as it is humanity’s best way of grasping objective reality, and therefore coming to an awareness of God beyond our own sublunary delusions.28 So potent was mathematics in comprehending the laws of reality that by its study, Dee suggested, mathematicians could come to the understanding of things otherwise reserved only for those who had been given divine revelations. Gaining skill in mathematics was, itself, a process of revelation, and might function to elevate men to divine wisdom even if no further dispensations from God were forthcoming.29 Cornelius Agrippa had likewise expressed the relation of mathematics to operative magic, stating that “the doctrines of mathematics are so necessary to, and have such an affinity with magic, that they do profess it without them, are quite out of the way, and labor in vain, and shall in no wise obtain their desired effect.”30 Indeed, Dee complained that his skill in mathematics was the very root of his reputation as a malevolent sorcerer.31

Fig. 6.1. The cover of Euclid’s Elements of Geometry, 1570 John Daye edition. Note the image of Hermes in the bottom center.

With his preface to the Elements, Dee would crown his early studies into reality, even as his career suffered from public accusations and royal indifference. From here, Dee would pass into exercising what he knew, impacting history so profoundly that we are still coping with the effects.